Abstract

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common cancer in men throughout the world, and the main cause of cancer death. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) act as crucial regulators in many human cancers. In this research, we measured the expression level of novel lncRNAs and their associated micro-RNAs (miRNAs) in PCa. In the present research, three lncRNAs were selected using the Mitranscriptome projec (CAT2064, CAT2042, and CAT2164.2). Samples of prostate tissue (20 PCa, and 20 BPH) and blood (14 PCa, and 14 BPH) were collected and the Real-time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) was used to measure the expression levels of the lncRNAs and their associated miRNAs. Based on our results, CAT2064 was significantly increased and CAT2042 was significantly decreased in human PCa tissue in comparison with BPH tissue. To discriminate PCa from BPH, CAT2064 (P < 0.05; 0.8750 AUC-ROC) showed a better potential as a diagnostic molecular biomarker compared to CAT2042 (P < 0.05; 0.8454 AUC-ROC). Furthermore, RT-qPCR results measured in blood samples from PCa patients showed a higher expression level of CAT2064 (P < 0.0001; AUC-ROC value of 0.8914) in comparison to CAT2042. CAT2064 and CAT2042 showed a positive correlation with the expression of miR-5095 and miR-1273a (r = 0.02885, 0.3202; P = 0.9413, 0.2266, respectively). CAT2064 and CAT2042 also had a negative correlation with miR-1304-3p and miR-1285-5p (r = − 0.3877, − 0.09330; P = 0.15, 0.7311, respectively). Collectively, CAT2064 and CAT2042 and their miRNA targets may constitute a regulatory network in PCa, and could serve as novel biomarkers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12291-021-00999-6.

Keywords: PCa, lncRNA, miRNA, BPH, Biomarker

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most prevalent cancer among men in the world, but in American and European men is the most widespread cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death [1]. The lack of highly effective diagnotic biomarkers for early detection reduces the overall survival of patients with PCa. Although many efforts have been made to discover new therapeutic strategies for PCa, the prognosis of patients with advanced disease remains poor. Identification of new genetic markers, and the evaluation of molecular processes associated with tumorigenesis in PCa is an important step to improve the diagnosis and treatment of this cancer [2]. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is one of the most well-known diagnostic markers in PCa, but it has limitations and is not completely specific [3]. Therefore, discovering new specific biomarkers for PCa detection is a worthwhile goal. One approach is to identify specific genes whose expression is significantly different between samples of PCa and benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). Several specific PCa biomarkers have recently been identified, including PCA3, TMPRSS2-ERG [4], and MALAT1 [5]. However, research into new diagnostic markers is still ongoing.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a group of heterogeneous RNA transcripts that play a pivotal role in various cellular processes such as, cell development, stem cell pluripotency, differentiation, and cancer progression [6]. The dysregulation of lncRNAs has been reported in several types of cancer. LncRNAs have been found to be able to play either an oncogenic function or a tumor-suppressor role, depending on the cancer type and stage of progression. In previous studies, some lncRNAs have been identified whose expression was related to PCa. These include, ANRIL [7], and PCAT-1[8] which were up-regulated in PCa. However, further investigations into the functional role and mechanism of action of new lncRNAs are needed to find more specific biomarkers for the development of PCa.

The Mitranscriptome project is a server database based on RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data from different human cancer types, which was published in 2015 by Matthew et al. It contains comprehensive information about the altered expression of lncRNAs in a variety of cancer types [9]. A large number of RNA seq libraries were obtained from normal and tumor tissues and cell lines, and finally 7942 lncRNAs were found to be associated with cancer.

Although the crucial role of lncRNAs in many cellular processes has been confirmed in several studies, the function of most of them still remains unknown. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate their role in cancer initiation, and progression, and whether they could be used in the early detection of cancer. Hence, in the present study, three lncRNAs, CAT2064, CAT2042, and CAT2164.2 that had been identified in RNA seq studies as PCa-related genes were selected from the MiTranscriptome project. The differences between their expression levels, specificity and sensitivity were evaluated between samples from patients with either PCa or BPH. In the next step, we selected the miRNAs that were associated with the studied lncRNAs, and evaluated their expression level in PCa and BPH samples.

Materials and Methods

In Silico Studies

In the first step of the study, we selected lncRNAs from the Mitranscriptome project (http://mitranscriptome.org/). This contains human long poly-adenylated RNA transcripts according to computational analysis of high-throughput RNA-Seq data from over 6,500 samples spanning different cancer and tissue types. We selected three lncRNAs (CAT2064, CAT2042, and CAT2164.2) with the highest expression level (Fragments per Kilobase per million (FPKM) value) for further analysis. Moreover, based on data obtained from Reg RNA 2.0 (http://regrna2.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/detection.html), we identified the miRNAs to which the selected lncRNAs were predicted to have binding sites. We selected miRNAs with a higher score and a negative Minimum Free Energy for the following analysis. Finally, RNAhybrid 2.2 (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni bielefeld. de/rnahybrid?id = rnahybrid) was used to identify the lncRNA and miRNA binding sites.

Cell Lines

PC3 and LNCaP, two human PCa cell lines, were obtained from the National Cell Bank (Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran) and cultured in RPMI1640 medium (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Patients

A total of 20 PCa tissue samples, as well as 20 BPH tissue samples (a total of 40 samples) were obtained from Ayatollah Kashani Hospital (Shahrekord, Iran). Following examination of radical prostatectomy samples by a pathologist, the tumor sections were carefully excised. The tumor Gleason scores were specified by the pathology department of Ayatollah Kashani Hospital (Shahrekord, Iran). Fresh specimens were stored in liquid nitrogen at − 180 °C until use in further experiments. The clinicopathological features of the participants are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

A total of 28 blood samples (from 14 PCa and 14 BHP patients) were also collected from Ayatollah Kashani Hospital (Shahrekord, Iran). These participants had not received any anticancer therapy before admission. Moreover, written informed consent was obtained from each patient before participation. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahrekord University of Medical Science (Shahrekord, Iran). Blood samples were stored in tubes with ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) at − 20 °C.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissue and blood samples as described previously [10, 11]. The quality and quantity of the extracted RNA were measured by 1.5% agarose gel and a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). cDNAs were then synthesized from total RNA using random hexamer primers. To detect the lncRNA expression in prostate cell lines, RT-PCR was carried out with the red Ampliqon PCR master mix (Ampliqon, Denmark) under optimized conditions.

In the next step, quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using 2X SYBR Green PCR Mix (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer instructions. The primer sequences of the aforementioned lncRNAs are shown in Supplementary Table.3. The β-Actin gene was used as an internal control gene. To investigate the miRNA expression level, after total RNA extraction, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized by a polyadenylation reaction following extension by BON RT primer (BON209002, Bon Yakhteh Company, Tehran, Iran). miRNA expression analysis was then performed using the BonMiR kit (BON209002, Bon Yakhteh Company, Tehran, Iran) with the specific forward primer and universal reverse primer. The Snord gene was used as the reference gene for normalization of the miRNA expression level. Quantitative Real-time PCR reactions were carried out on the Rotor-Gene 6000 instrument (Corbett Life Science, Sydney, Australia). The relative expression of the genes was computed by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Data Analysis

All of the experimental procedures were performed three times. Statistical significance was assessedd by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Pearson’s correlation method for the normal distribution of the data and correlation tests, respectively. Moreover, the ROC curve was used to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the biomarkers. All of the analysis was done using PRISM 6.07 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). P-value < 0.05 was defined as a statistically significant level.

Results

In Silico Studies

From the data of the Mitranscriptome project, we selected three lncRNAs with a high differential expression level in prostate cancer. Accordingly, up-regulation of CAT2064, as well as down-regulation of CAT2042 and CAT2164.2, were reported in PCa (Fig. 1a, b, c). After that, we selected the miRNAs that possessed binding sites on the aforementioned lncRNAs. The miRNAs hsa-miR-1304-3p and hsa-miR-5095 were predicted for CAT2064, while hsa-miR-1285-5p and hsa-miR-1273a were predicted for CAT2042. No known miRNA was predicted to interact with CAT2164.2.

Fig. 1.

Bioinformatics studies. a Up-regulation of CAT2064 in PCa versus normal samples. b and c down-regulation of CAT2042 and CAT2164.2 in PCa versus normal samples based on Mitranscriptome project (Color Code: Cancer (Left); Normal (Right))

Expression of CAT2064, CAT2042, and CAT2164.2 in PC3 and LNCaP Cell Lines, and in PCa and BPH Tissue Samples

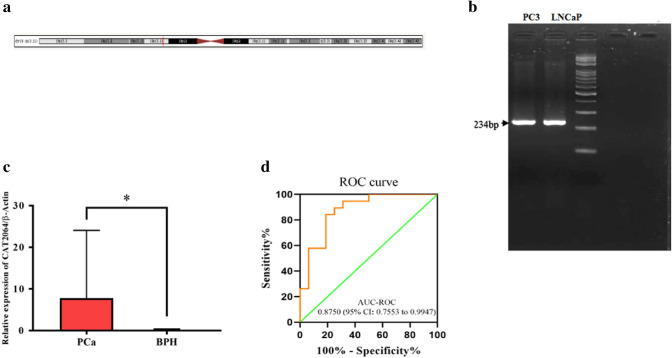

In order to determine the optimum conditions for amplification of the selected lncRNAs in PC3 and LNCaP cell lines, the RT-PCR technique was used. The chromosomal locations of the CAT2064 and CAT2042 are shown in Fig. 2a and 3a. Our results indicated that the three candidate lncRNAs were expressed in both cell lines (Fig. 2b, 3b). RT-qPCR was used to examine the quantitative expression levels of these lncRNAs in 20 PCa tissue and 20 BPH samples. The CAT2064 and CAT2042 expression levels were found to be significantly higher and lower in tumor samples compared to BPH specimens, respectively (P < 0.05; Fig. 2c, 3c). The expression of the other candidate lncRNA, CAT2164.2 showed no significant difference between the PCa and BPH samples (data not shown). The up-regulation of CAT2064 and the down-regulation of CAT2042 were on average 688 fold and 0.2 fold. Our findings from the ROC curve analysis showed that CAT2064 and CAT2042 lncRNAs had AUC-ROC values of 0.8750 and 0.9079, respectively (Fig. 2d, 3d).

Fig. 2.

CAT2064 lncRNA as a PCa biomarker. a Schematic representation of the chromosomal location of CAT2064 lncRNA b RT-PCR analysis of CAT2064 expression in PC3 and LNCaP cell lines. c Relative gene expression of CAT2064 in PCa and BPH samples. The gene expression was normalized with the β-actin reference gene, and obtained by the 2−ΔΔCt method. d ROC curve analysis showing the sensitivity and specificity of CAT2064 for diagnosis of the PCa in tissue specimens AUC = 0.8750 (95%CI: 0.7553–0.9947). All data are represented as mean ± SD

Fig. 3.

CAT2042 lncRNA as a PCa biomarker. a Schematic representation of the chromosomal location of CAT2042 lncRNA b RT-PCR analysis of CAT2042 expression in PC3 and LNCaP cell lines. c Relative gene expression of CAT2042 in tumor and BPH samples. The gene expression was normalized with the β-actin reference gene, and obtained by 2−ΔΔCt method. d ROC Curve analysis showing that CAT2042 had an AUC = 0.8454 (95%CI: 0.7144–0.9764) in PCa tissue samples. All data are represented as mean ± SD

Expression of hsa-miR-1304-3p, hsa-miR-5095, hsa-miR-1285-5p and hsa-miR-1273a in PCa and BPH Samples

After selecting miRNAs that were predicted to have binding sites on the chosen lncRNAs, we evaluated their expression levels in PCa and BPH samples. Our results demonstrated down-regulation of miR-1304-3p and miR-1273a, and up-regulation of miR-5095, and miR-1285-5p in PCa compared to BPH. All of the differential expression levels were statistically significant (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Expression of target miRNAs. a Differential expression of hsa-miR-1304-3p, hsa-miR-5095, hsa-miR-1285-5p and hsa-miR-1273a in tumor and BPH samples. b The expression of CAT2064 in blood samples of PCa patients. Its expression was quantified by real-time PCR in 14 BPH and 14 PCa blood samples, β-actin was used as the reference gene. All data are represented as mean ± SD. c ROC curve analysis showing the sensitivity and specificity of the CAT2064 as a biomarker in blood samples (AUC = 0.8914; 95% CI: 0.7805 to 1.000)

CAT2064 is Also Expressed in Blood Samples

To discover whether the selected lncRNAs were differentially expressed in the blood samples of patients, the RT-qPCR technique was carried out on the synthesized cDNA from blood samples of 14 PCa and 14 BPH patients. The results showed that only the CAT2064 expression level was significantly higher in the blood samples of PCa patients in comparison to BPH patients (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4b). The results of the ROC curve analysis showed that CAT2064 had an AUC-ROC value equal to 0.8914 and the sensitivity and specificity were 71.875 and 68.42, respectively (Fig. 4c).

Negative Correlation Between CAT2064 and CAT2042 Expression in Tumor Specimens

To explore the relationship between the expression of selective lncRNAs, the Pearson correlation was computed according to compare the expression levels of CAT2064 and CAT2042 in tumor samples. Our findings showed a negative correlation between the expression levels of these lncRNAs with a correlation coefficient of -0.1170, which was not statistically significant (P-value: 0.66) (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Correlation of gene expression. a Negative correlation (r = − 0.1170) between CAT2064 and CAT2042 expression. b Negative correlation between CAT2064 and hsa-miR-1304-3p (r = − 0.3877) c. Positive correlation between CAT2064 and hsa-miR-5095 (r = 0.02885). d Negative correlation between CAT2042 and hsa-miR-1285-5p (r = − 0.09330). e Positive correlation between CAT2042 and hsa-miR-1273a (r = 0.3202)

Negative and Positive Correlation Between CAT2064 and Either miR-1304-3p or miR-5095 in Tumor Specimens

The expression levels of miR-1304-3p and miR-5095 in PCa samples showed a negative and positive correlation between the expression level of CAT2064. CAT2064 and miR-1304-3p (r = − 0.3877) and CAT2064 and miR-5095 (r = 0.02885) but these correlations were not statistically significant (P-value: 0.15 and 0.9413, respectively) (Fig. 5b, c).

Negative and Positive Correlation of CAT2042 With miR-1285-5p or miR-1273a in Tumor Specimens

Moreover, a negative correlation between CAT2042 and miR-1285-5p (r = − 0.09330) expression was found which was not statistically significant (P-value: 0.7311) (Fig. 5d). On the other hand, a non-significant positive correlation was found between CAT2042 and miR-1273a expression (r = 0.3202, P-value: 0.2266) (Fig. 5e).

Discussion

In the past few years, many studies have shown the vital role of lncRNAs and miRNAs in cancer initiation and disease progression [12]. Functionally, some over-expressed lncRNAs can cause inhibition of apoptosis and promotion of cell proliferation thus encouraging tumorigenesis and cancer progression [13]. Although several efforts have been conducted to discover novel molecular biomarkers, the prognosis of patients with advanced PCa remains disapppinting. PSA has been used as a screening marker for PCa; however, it is not completely specific PCa and leads to a negative biopsy rate in 70–80% of cases. Recently, PCA3 has been described as another new biomarker, and is moving into clinical application to reduce unnecessary prostate biopsies. LncRNAs are emerging as potential biomarkers for many different diseases and cancer types [14].

In our current study, we evaluated whether these three lncRNAs, CAT2064, CAT2042, and Cat2164.2 could be involved in tumorigenesis in PCa. CAT2064 and CAT2042 were respectively up-regulated and down-regulated in human PCa tissues, compared to the BPH samples. Moreover, increased expression of CAT2064 was observed in blood samples of PCa patients compared to the BPH paients, suggesting that a non-invasive screening approach might be feasible.

To date, a few lncRNAs have been found to be specific for PCa. Sequencing of the PCa transcriptome has revealed that about a quarter of the transcripts were lncRNAs (or derived from other unannotated transcripts), suggesting that lncRNAs could play a larger role in various aspects of prostate cancer [15]. In this regard, determining the putative role of these genes in the initiation and progression of PCa, may provide new therapeutic markers for early diagnosis and screening.

CAT2064 and CAT2042 are two lncRNAs that could be used as biomarkers for PCa diagnosis. Based on the results of our study CAT2064 showed a better diagnostic value than the others, with an AUCROC value 0.8750. The high difference in expression levels between PCa and BPH samples suggests that these lncRNAs could be suitable biomarkers for diagnosis of the disease. These results confirmed the previous data obtained from the Mitranscriptome project.

To confirm whether these candidate lncRNAs could be detected in a non-inasive fashion within biofluid samples, the expression was also quantified in blood samples from PCa and BPH patients. Based on the results of our real-time RT-qPCR analysis, the expression of CAT2064 was significantly different between PCa and BPH blood samples. The sensitivity and specificity values of this biomarker were 71.875, and 68.42 respectively. These observations suggest that CAT2064 lncRNA could be a better marker for PCa diagnosis, than (for instance) PCA3 with 47% to 69% sensitivity, and 66–83% specificity. Similarly, Bayat et al. [15] proposed that two other lncRNAs called Prcat17.3 and Prcat38 could be used alone or in combination with PCA3 for the diagnosis of PCa.

Micro-RNAs (miRNAs), are a group of small single-stranded RNAs that are 18–25 nucleotides in length. They play pivotal roles in biological processes like embryonic development, tissue formation, and stem cell differentiation, by negative regulation of mRNA transcripts[16]. MiRNAs are conserved non-coding RNAs that regulate the expression of a broad range of genes via post-transcriptional silencing. The dysregulation of miRNA expression found in prostate and other cancers, has confirmed their role in cancer biology [17]. To date, a wide range of different cancer-associated miRNAs have been reported [18].

In addition to the fact that both miRNAs and lncRNAs can regulate the expression of mRNAs, it has been suggested that they can also interact with each other, thereby further increasing their effect on the transcriptome. In addition to miRNA-triggered RNA degradation, there can be competition between miRNAs and lncRNAs for the same mRNA target, miRNAs can undergo maturation from lncRNAs, and lncRNAs can act as decoys for miRNAs [19]. Several studies have suggested that the latter is the most common mechanism of interaction of lncRNAs and miRNAs in cancer. These mechanisms have been much investigated in the past few years, because of the vast complexity of the possible lncRNA-miRNA interactions. These investigations have resulted in the introduction of bioinformatic platforms, like MechRNA [20], RNAHybrid [21], RNADuplex [22], and RNAcofold [23], which are all designed to evaluate interactions between lncRNAs and miRNAs.

In the present study, we identified four miRNAs that possessed predicted binding sites to the two studied lncRNAs, and evaluated their expression levels in PCa and BPH samples. The two miRNAs with predicted binding to CAT2064 showed differences, with miR-1304-3p being significantly down-regulated, and miR-5095 being significantly up-regulated in PCa compared to BPH samples. According to a previous study, miR-1304 can act as a tumor suppressor gene, suppressing cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, and inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [24]. Therefore, the decreased expression of miR-1304 in PCa samples would be logical if it acted as a tumor suppressor gene. Moreover, up-regulation of miR-5095 in PCa samples is in accordance with the results of another study on miRNAs in cervical cancer, in which up-regulation of miR-5095 was also observed in tumor samples compared to normal samples. It has been suggested that BCL2, a well-known tumor promoting gene that suppresses apoptosis, is a target of miR-5095 [25]. The up-regulation of miR-1285-5p in PCa samples suggested its oncogenic role, which is in line with the results of a study in NSCLC where it was found to target Smad4 and CDH1. Finally, miR-1273a showed decreased expression in PCa compared to BPH samples. No study has yet been performed on the role of miR-1273a in cancer. In one recent study, miR-1273 g-3p was reported to be involved in anthracycline-induced cardiac toxicity, by affecting the TGF-β signaling pathway and the adhesion signaling pathway [26]. Moreover, down-regulation of miR-1273 g-3p was also detected in epithelial ovarian cancer, associated with the regulation of the TNF-α, COL1A1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 genes [27].

Based on our results, CAT2064 showed a negative correlation with miR-1304-3p, and a positive correlation with miR-5095 expression. Likewise, CAT2042 had a negative correlation with miR-1285-5p and a positive correlation with miR-1273a. These observations confirmed that CAT2064 could act as a tumor promoter, and that CAT2042 could act as a tumor suppressor, and both could be used as biomarkers in PCa.

To our knowledge, several studies have reported both the oncogenic or tumor suppressor roles of lncRNAs in PCa. In one study, it was demonstrated that lncRNA FOXP4-AS1 played a regulatory role in the tumorigenesis of PCa [28]. Other studies also suggested that lncRNA-p21 could act as a biomarker for the progression of PCa [29]. On the other hand, several additional candidate miRNAs including, miR-1, miR − 21, miR − 106b, miR − 141, miR − 145, miR − 205, miR − 221, and miR − 375, have been suggested as promising biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of PCa [30].

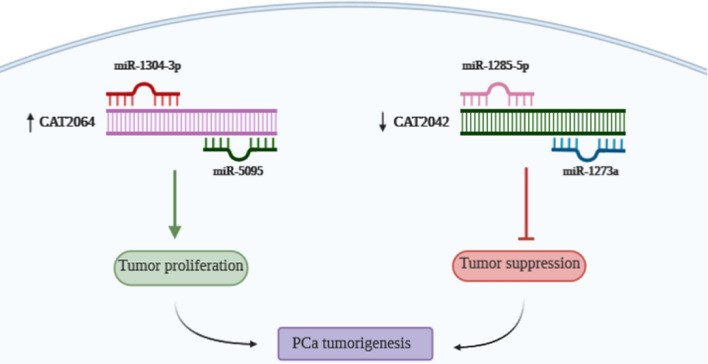

In this study, for the first time, we found that two new lncRNAs CAT2064 and CAT2042, and their miRNA targets may constitute a regulatory network in PCa, and could act as an oncogene and a tumor suppressor gene, respectively (Fig. 6). These molecules could act as novel biomarkers for PCa in the future, although additional studies in larger populations will be required for final confirmation. Knock-down and over-expression experiments are required to elucidate the proposed pathway involving miRNAs and target genes.

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram representing the involvement of lncRNAs and their targeted miRNAs in prostate cancer

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff of Ayatollah Kashani Hospital (Shahrekord, Iran) for their valuable support. MRH was supported by US NIH Grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700.

Authors' contribution

Farzane Amirmahani: Conception, design, data analysis, interpretation, and final approval of manuscript. Nasim Ebrahimi: Conception and design, data analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of manuscript. Rafee Habib Askandar: Lab experimentations, collection and/or assembly of data. Marzieh Rasouli Eshkaftaki: Primary analysis of the data, manuscript writing. Katayoun Fazeli: Primary analysis of the data, manuscript writing. Michael R Hamblin: Editing for intellectual content and final approval of manuscript.

Funding

MRH was supported by US NIH Grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences ethical committee.

Consent to participate

A written informed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Farzane Amirmahani and Nasim Ebrahimi have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Farzane Amirmahani, Email: F.mahani@sci.ui.ac.ir.

Nasim Ebrahimi, Email: nasimeb69@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Rawla P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J Oncol. 2019;10(2):63. doi: 10.14740/wjon1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang G, Zhao D, Spring DJ, et al. Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2018;32(17–18):1105–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.315739.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pannek J, Partin A. Prostate-specific Antigen: What's new in Oncology (Williston Park). 1997. [PubMed]

- 4.Magi-Galluzzi C, Tsusuki T, Elson P, et al. TMPRSS2–ERG gene fusion prevalence and class are significantly different in prostate cancer of caucasian, african-american and japanese patients. Prostate. 2011;71(5):489–497. doi: 10.1002/pros.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ren S, Liu Y, Xu W, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 is a new potential therapeutic target for castration resistant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190(6):2278–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czerwinska P, Kaminska B. Regulation of breast cancer stem cell features. Contemp Oncol. 2015;19(1A):A7. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotake Y, Nakagawa T, Kitagawa K, et al. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15 INK4B tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2011;30(16):1956–1962. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Balbin OA, et al. Transcriptome sequencing across a prostate cancer cohort identifies PCAT-1, an unannotated lincRNA implicated in disease progression. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(8):742–749. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):199. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammadi M, Amirmahani F, Goharrizi KJ, et al. Evaluating the expression level of Survivin gene in different groups of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients of Iran. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46(3):2679–2684. doi: 10.1007/s11033-019-04703-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ansari MH, Irani S, Edalat H, et al. Deregulation of miR-93 and miR-143 in human esophageal cancer. Tumor Biol. 2016;37(3):3097–3103. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3987-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamalvandi M, Motovali-bashi M, Amirmahani F, et al. Association of T/A polymorphism in miR-1302 binding site in CGA gene with male infertility in Isfahan population. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45(4):413–417. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böttcher R. Identification of Novel Prostate Cancer Biomarkers Using High-throughput Technologies. (2016).

- 14.Fatima R, Akhade VS, Pal D, et al. Long noncoding RNAs in development and cancer: potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Molecular and cellular therapies. 2015;3(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s40591-015-0042-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayat H, Narouie B, Ziaee SAM, et al. Two long non-coding RNAs, Prcat17. 3 and Prcat38, could efficiently discriminate benign prostate hyperplasia from prostate cancer. Prostate. 2018;78(11):812–818. doi: 10.1002/pros.23538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams BD, Kasinski AL, Slack FJ. Aberrant regulation and function of microRNAs in cancer. Curr Biol. 2014;24(16):R762–R776. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klinge CM. Non-coding RNAs: long non-coding RNAs and microRNAs in endocrine-related cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25(4):R259–R282. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez R, Sanchez-Jimenez E, Melguizo C, et al. Downregulated microRNAs in the colorectal cancer: diagnostic and therapeutic perspectives. BMB Rep. 2018;51(11):563. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2018.51.11.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon J-H, Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Elsevier; 2014. Functional interactions among microRNAs and long noncoding RNAs; pp. 9–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gawronski AR, Uhl M, Zhang Y, et al. MechRNA: prediction of lncRNA mechanisms from RNA–RNA and RNA–protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3101–3110. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krüger J, Rehmsmeier M. target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic acids research. 2006;34: W451-W454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Zu Siederdissen CH, et al. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Alg Molecul Biol. 2011;6(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proctor JR, Meyer IM. C o F old: an RNA secondary structure prediction method that takes co-transcriptional folding into account. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(9):e102–e102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C-g, Pu M-f, Li C-z, et al. MicroRNA-1304 suppresses human non-small cell lung cancer cell growth in vitro by targeting heme oxygenase-1. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2017;38(1):110–119. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reshmi G, Chandra SV, Babu VJM, et al. Identification and analysis of novel microRNAs from fragile sites of human cervical cancer: computational and experimental approach. Genomics. 2011;97(6):333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yadi W, Shurui C, Tong Z, et al. Bioinformatic analysis of peripheral blood miRNA of breast cancer patients in relation with anthracycline cardiotoxicity. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01346-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Günel T, Gumusoglu E, Dogan B, et al. Potential biomarker of circulating hsa-miR-1273g-3p level for detection of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298(6):1173–1180. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4913-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu X, Xiao Y, Zhou Y, et al. LncRNA FOXP4-AS1 is activated by PAX5 and promotes the growth of prostate cancer by sequestering miR-3184-5p to upregulate FOXP4. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(7):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1699-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peinado P, Herrera A, Baliñas C et al. (2018) Long noncoding RNAs as cancer biomarkers. In: Cancer and Noncoding RNAs. Elsevier, pp 95–114

- 30.Luu HN, Lin H-Y, Sørensen KD, et al. miRNAs associated with prostate cancer risk and progression. BMC Urol. 2017;17(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.