Abstract

Simple Summary

Given the low incidence, heterogeneous behavior, and diverse anatomical sites of salivary gland cancer (SGC), there are a limited number of clinical studies on its management. This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to report the cumulative evidence on postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) for SGC of the head and neck. Based on 2962 patients with SGC from 26 studies, this study demonstrated the long-term survival and toxicities of PORT as a local treatment modality for SGC. Considering the suboptimal disease-free survival and distant metastasis-dominant recurrent patterns, however, an intensified treatment strategy is needed.

Abstract

Background: Because of the rarity, heterogeneous histology, and diverse anatomical sites of salivary gland cancer (SGC), there are a limited number of clinical studies on its management. This study reports the cumulative evidence of postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) for SGC of the head and neck. Methods: A systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. We searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases between 7th and 10th November 2023. Results: A total of 2962 patients from 26 studies between 2007 and 2023 were included in this meta-analysis. The median RT dose was 64 Gy (range: 56–66 Gy). The median proportions of high-grade, pathological tumor stage 3 or 4 and pathological lymph node involvement were 42% (0–100%), 40% (0–77%), and 31% (0–75%). The pooled locoregional control rates at 3, 5, and 10 years were 92% (95% confidence interval [CI], 89–94%), 89% (95% CI, 86–93%), and 84% (95% CI, 73–92%), respectively. The pooled disease-free survival (DFS) rates at 3, 5, and 10 years were 77% (95% CI, 70–83%), 67% (95% CI, 60–74%), and 61% (95% CI, 55–67%), respectively. The pooled overall survival rates at 3, 5, and 10 years were 84% (95% CI, 79–88%), 75% (95% CI, 72–79%), and 68% (95% CI, 62–74%), respectively. Severe late toxicity ≥ grade 3 occurred in 7% (95% CI, 3–14%). Conclusion: PORT showed favorable long-term efficacy and safety in SGC, especially for patients with high-grade histology. Considering that DFS continued to decrease, further clinical trials exploring treatment intensification are warranted.

Keywords: postoperative radiotherapy, radiotherapy, salivary gland cancer

1. Introduction

Salivary gland cancer (SGC) is a rare malignancy that accounts for less than 5% of all head and neck cancers and encompasses a widely heterogeneous histology, with more than 20 different subtypes, according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification [1]. The most common subtypes include mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), acinic cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC), carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (Ca ex PA), and adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified [2]. In addition, SGC exhibits different rates of incidence and prevalence depending on the anatomical site [3]. Most cases occur in the parotid gland, followed by submandibular, sublingual, and minor salivary glands [4]. The probability of cancer in a parotid mass ranges from 15% to 32% compared to that from 41% to 50% in a submandibular mass, 70% to 90% in minor salivary gland masses, and almost 100% in sublingual masses [5]. Given the low incidence, heterogeneous behavior, and diverse anatomical sites of SGC, there are limited clinical studies on its management. Additionally, only a few guidelines have recently been published to provide relevant practical recommendations for patients with SGC [6,7,8,9,10].

Although there are no randomized trials comparing surgery alone with surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy (PORT) in patients with SGC of the head and neck, several retrospective studies have shown the effectiveness of PORT in patients with adverse prognostic factors. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines recommend that PORT should be offered to all patients with resected ACC and those with high-grade tumors, positive resection margin (RM), lymph node (LN) metastases, perineural invasion (PNI), lymphovascular invasion (LVI), or T3–4 tumors [6]. PORT may be offered to patients with close RM or intermediate-grade tumors. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)—European Reference Network on Rare Adult Solid Cancers (EURACAN) guidelines recommend PORT for patients with T3–4, high/intermediate-grade tumors, close and/or positive RM, and/or PNI [7]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend PORT as the preferred modality for patients with T3–4, LN metastases, high/intermediate-grade tumors, close or positive RM, PNI, and/or LVI [9]. However, these guidelines and consensus were mainly based on retrospective studies with a limited number and great heterogeneity among the study patients. To date, there are no meta-analyses about treatment outcomes encompassing the diverse and heterogeneous features of SGC treated with PORT.

Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to report the cumulative evidence on PORT for SGC of the head and neck.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [11]. Although prospective registration of systemic reviews is generally recommended, there is no information on the overall processing time in PROSPERO, and some state that it may take up to several months [12]. A recent study reported the median time from registering a protocol in PROSPERO to publication was 16 months [13]. This systematic review and meta-analysis was designed as an international cooperative research study and conducted on schedule without registration in PROSPERO.

2.1. Study Search

A literature search was conducted using the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases between 7th and 10th November 2023. The keywords used regarding the patient/problem, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) model are listed in Supplementary Table S1. We cooperated with a professional librarian at the Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon, to develop and review the search strategy. Studies on humans published in English from 1974 to 2023 were included. In addition, the reference lists of the review articles, relevant studies, and clinical practice guidelines were reviewed. A total of 5178 articles were identified, and three authors (J. Wang, X. Guo, and J. Yu) independently screened the article titles, abstracts, and full texts as necessary. Disagreements were resolved by a fourth author (S.H. Bae).

2.2. Selection Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) original studies including randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized clinical trials, case series, or observational studies on SGC of head and neck; (2) primary SGC diagnosed as per the WHO classification; (3) the inclusion of ≥10 patients who received surgery followed by PORT with curative intent; (4) the use of megavoltage equipment; (5) reporting of at least ≥2 years locoregional control (LRC) and/or survival and/or toxicities. In the absence of numerical data, the LRC and survival were assumed indirectly using descriptive plots. In cases of multiple studies from one institution with overlapping patients, the following criteria were applied to determine inclusion and were prioritized in numerical order: (1) studies that described treatment outcomes of SGC patients treated with PORT in detail, (2) studies with the largest number of patients, and (3) the most recently published study. Studies from the same institution were independently categorized if they were conducted during different periods. Additionally, the two treatment groups in one study were independently categorized if LRC and survival were reported separately. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) reviews, letters, comments, replies, editorials, and other nonoriginal studies, (2) duplicate patient data, (3) recurrent and/or metastatic SGC, (4) previous RT history for head and neck cancer, (5) intraoperative radiotherapy, (6) 60Co gamma ray, neutron therapy, brachytherapy, Gamma Knife, and charged-particle therapy.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction was carried out independently by four authors using a standardized form, and the following data were obtained: (1) study, patient, and tumor characteristics; (2) treatment; (3) survival; and (4) late toxicity. Survival rates at 3–10 years were investigated. For studies lacking reported survival rates while having available survival curves, the corresponding numeric rates were extracted from the survival curves by employing the Engauge Digitizer (version 12.1, http://markummitchell.github.io/engauge-digitizer. accessed on 5 December 2023). Late toxicities were defined according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events or toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (RTOG/EOTRC). The overall incidence of late toxicities and severe toxicities ≥ grade 3 was assessed.

Because most studies were retrospective, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess study quality [14]. Studies with over 7 points were categorized as high-quality, and studies with scores 4–6 were categorized as medium-quality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the Higgins I2 statistic [15]. An I2 value > 50% corresponded to substantial heterogeneity. Given the variations in treatment decision-making and the periods for which the study was applicable, the random-effects model was considered superior to the fixed-effects model when calculating pooled estimates. The DerSimonian and Laird method was applied for the random-effects analysis, and we present both estimates in the tables [16]. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s regression tests. If the funnel plot was symmetrical or the p-value exceeded 0.05 in Egger’s test, then the null hypothesis of no publication bias was accepted. For comparison between subgroups, a Q test based on an analysis of variance and a random effects model was used, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Rex Excel-based statistical analysis software, version 3.6.0 (RexSoft, Seoul, Republic of Korea, http://rexsoft.org/).

Table 1.

Study details for salivary gland carcinoma treated with surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy.

| Author | Country | Study Type | NOS | Time of Study | No. | Anatomical Site | Histology (%) | Grade H/I/L (%) |

Surgery Type (%) | RT Technique | Median Total Dose (Gy) (Range) | RT Target | Post-op CCRT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yan, 2023 [17] | China | S/R | 5 | 2004–2020 | 418 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | 22/0/78 | - | 3D, IMRT | - | - | 11 |

| Park, 2023 [18] | Korea | M/R | 6 | 2004–2019 | 118 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | 42/8/50 | P (83)/P + LND (17) | 3D, IMRT | 63 (54–78.75) | TB (71)/TB + NI (29) | 2 |

| Duru Birgi, 2023 [19] | Turkey | S/R | 6 | 2013–2018 | 18 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | - | P (67)/ P + LND (33) |

IMRT | 66 (60–70) | TB (39)/TB + NI (61) | 17 |

| Hsieh_A, 2023 [20] | Taiwan | M/R | 7 | 2000–2015 | 263 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 72/28 a | P ± LND | 3D, IMRT | 62 ± 9 b | TB + NI | 0 |

| Hsieh_B, 2023 [20] | Taiwan | M/R | 7 | 2000–2015 | 148 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 88/12 a | P ± LND | 3D, IMRT | 65 ± 8 b | TB + NI | 100 |

| Zang, 2022 [21] | China | S/R | 5 | 2009–2016 | 60 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | - | P (30)/ P + LND (70) |

IMRT | 63 (60–68) | TB (7)/TB + NI (93) | 7 |

| Franco, 2021 [22] | USA | S/R | 5 | 2008–2020 | 72 | All salivary glands | All subtypes excluding ACC | - | - | IMRT | - | - | 42 |

| Dou, 2019 [23] | China | S/P2 | 6 | 2016–2018 | 52 | All salivary glands | Intermediate or high-grade histology | - | - | IMRT | NR (60–66) | - | 100 |

| Nutting_A, 2018 [24] | UK | M/P3 | 7 | 2008–2013 | 54 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | 43/17/30 | - | 3D | 65 (58–65) | TB+/−NI | 0 |

| Nutting_B, 2018 [24] | UK | M/P3 | 7 | 2008–2013 | 56 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | 32/20/38 | - | IMRT | 65 (60–65) | TB+/−NI | 0 |

| Nishikado, 2018 [25] | Japan | S/R | 4 | 1999–2007 | 58 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | - | - | - | 60 c (NR) | - | 0 |

| Li, 2018 [26] | China | M/P2 | 6 | 2013–2016 | 20 | All salivary glands | Intermediate/high-grade histology | 40/60/0 | - | 3D, IMRT | 66 (NR) | TB + NI | 100 |

| Gebhardt, 2018 [27] | USA | S/R | 6 | 2002–2015 | 128 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 45/23/24 | P (47)/ P + LND (53) |

IMRT | 66 (45–70.2) | TB (17)/TB + NI (83) | 22 |

| Boon, 2018 [28] | Netherland | M/R | 5 | 2000–2016 | 15 | All salivary glands | Secretory carcinoma with ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene | 0/0/100 | P ± LND | - | 66 (60–66) | TB (27)/TB + NI (27) | 0 |

| Zhang, 2017 [29] | China | S/R | 5 | 2008–2014 | 30 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | - | P (33)/ P + LND (67) |

2D, IMRT | NR (60–70) | TB+/−NI | 0 |

| Gutschenritter, 2017 [30] | USA | S/R | 4 | 2002–2014 | 78 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | - | P ± LND | 3D, IMRT | NR (50–66) | - | 0 |

| Sayan, 2016 [31] | USA | S/R | 5 | 2006–2015 | 20 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | - | P (60)/ P + LND (40) |

3D, IMRT | 60 (NR) | TB (55)/TB + NI (45) | 0 |

| Mifsud_A, 2016 [32] | USA | S/R | 6 | 1998–2013 | 103 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 37/26/29 | - | - | 64 (45–72) d | - | 0 |

| Mifsud_B, 2016 [32] | USA | S/R | 6 | 1998–2013 | 37 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 73/5/11 | - | - | 64 (45–72) d | - | 100 |

| Hosni, 2016 [33] | Canada | S/R | 7 | 2000–2012 | 304 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | 41/21/38 | P (49)/ P + LND (51) |

3D, IMRT | 66 (46–74) | TB (62)/TB + NI (38) | 3 |

| Haderlein, 2016 [34] | Germany | S/R | 5 | 2000–2014 | 63 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 64/19/14 | P (6)/ P + LND (94) |

3D, IMRT | 64 (45–74) | TB (25)/TB + NI (75) | 46 |

| Kaur, 2014 [35] | India | S/R | 5 | 1998–2008 | 39 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | - | P ± LND | 2D, 3D | 60 (24–64) | - | 0 |

| Tam, 2013 [36] | USA | S/R | 6 | 1990–2011 | 200 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | - | P (64)/ P + LND (36) |

2D, 3D, IMRT | 63 (60–66) | TB+/−NI | 10 |

| Chung, 2013 [37] | USA | S/R | 5 | 1998–2011 | 37 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes excluding ACC | - | P (65)/ P + LND (35) |

3D, IMRT | 60 (46–70) | TB+/−NI | 24 |

| Kim, 2012 [38] | Korea | S/R | 5 | 1998–2010 | 35 | Major salivary glands | Salivary duct carcinoma | 100/0/0 | P (11)/P + LND (89) | - | 59.4 (50.4–71.4) | TB + NI (100) | 9 |

| Al-Mamgani, 2012 [39] | Netherlands | S/R | 6 | 1995–2010 | 186 | Parotid gland | All subtypes | 40/10/41 | P (77)/ P + LND (23) |

2D,3D, IMRT | 66 (54–70) | TB+/−NI | 2 |

| Pederson, 2011 [40] | USA | M/R | 5 | 1991–2007 | 24 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | 79/0/21 | P (12)/ P + LND (88) |

2D,3D, IMRT | 65 (55–68) | - | 100 |

| Noh, 2010 [41] | Korea | S/R | 5 | 1995–2006 | 75 | Major salivary glands | All subtypes | 83/0/17 | P (64)/ P + LND (36) |

3D | 56 (54–70) | TB (73)/P + NI (27) | 0 |

| Chen, 2007 [42] | USA | S/R | 7 | 1960–2004 | 251 | All salivary glands | All subtypes | - | - | 2D,3D, IMRT | 63 (45–72) | TB (48)/TB + NI (52) | 4 |

S, single center; M, multicenter; R, retrospective study; P2, prospective phase 2 study; P3, prospective phase 3 study; NOS, the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; No., number of patients; NR, not reported; ACC, adenoid cystic carcinoma; H, high-grade; I, intermediate-grade; L, low-grade; P, primary resection; LND, lymph node dissection; 2D, two-dimensional radiotherapy; 3D, three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiotherapy; TB, tumor bed; NI, nodal irradiation; postop CCRT, postoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy. a means patients with a high grade versus patients with an intermediate/low grade. b means mean dose ± standard deviation. c means mean dose. d means the median dose which the entire patients received.

3. Results

3.1. Search Result

A total of 5164 studies were initially screened from the four databases, and 14 additional studies were added through cross-referencing. After excluding 1465 duplicate studies, the remaining 3713 studies were identified and screened. After screening the titles and abstracts, 64 studies were selected for full-text reviews. Finally, a total of 2962 patients from 26 studies were selected for this systematic review and meta-analysis, as shown in Figure 1 [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Among these, three studies separately analyzed the outcomes of patients who received PORT in two treatment groups, and each treatment group was categorized into a different cohort [20,24,32]. Therefore, a total of 29 cohorts were included in this study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) algorithm.

3.2. Selected Studies’ Characteristics

Table 1 and Table 2 present the characteristics of the 29 cohorts in 26 studies conducted between 2007 and 2023. Three studies were prospective, and the remaining were retrospective. The quality of each study according to the NOS is presented in Table 1.

Table 2.

Pathologic details and treatment outcomes for salivary gland carcinoma treated with surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy.

| Author | pTstage: 1/2/3/4(%) |

pNstage: 0/1/2/3(%) |

LVI (%) | PNI (%) | Median f/u (mo) | 3-yr LRC (%) |

5-yr LRC (%) |

10-yr LRC (%) |

3-yr DMFS (%) |

5-yr DMFS (%) |

10-yr DMFS (%) |

3-yr DFS (%) | 5-yr DFS (%) | 10-yr DFS (%) | 3-yr OS (%) | 5-yr OS (%) | 10-yr OS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yan [17] | 28/48/11/13 | 67/13/17/3 | 8 | 26 | 60 | - | - | - | 79 | 72 | 59 | - | - | - | 90 | 81 | 63 |

| Park [18] | 30/30/32/8 | 100/0/0/0 | 16 | 20 | - | 99 | 95 | - | - | - | - | 95 | 86 | - | - | - | - |

| Duru Birgi [19] | 22/45/11/0 | 56/11/11/0 | 0 | 11 | 30 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hsieh_A [20] | 30/33/19/18 | 85/3/12/0 | 13 | 39 | 131 c | 92 | 89 | 85 | - | - | - | 78 | 72 | 64 | 88 | 80 | 72 |

| Hsieh_B [20] | 13/36/24/27 | 58/9/33/0 | 20 | 49 | 131 c | 87 | 83 | 82 | - | - | - | 66 | 59 | 53 | 80 | 71 | 61 |

| Zang [21] | 23/7 a | 68/13/19/0 | - | 32 | 56 | 87 | 82 | 82 | 85 | 78 | 66 | 80 | 73 | 63 | 91 | 85 | 85 |

| Franco [22] | - | - | - | - | 41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dou [23] | - | - | - | - | 16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Nutting_A [24] | 30/28/13/22 | 59/7/26/0 | - | - | 50 c | - | - | - | - | - | - | 81 | - | - | 81 | - | - |

| Nutting_B [24] | 29/39/14/16 | 66/13/16/0 | - | - | 50 c | - | - | - | - | - | - | 81 | - | - | 86 | - | - |

| Nishikado [25] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 53 | - | - | - | - |

| Li [26] | - | - | - | 10 | 21 | 88 | - | - | 95 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Gebhardt [27] | 31/31/16/22 | 70/5/25/0 | 37 | 53 | 54 | - | 86 | - | - | 77 | - | - | 61 | - | - | 73.7 | - |

| Boon [28] | 47/47/0/0 | 93/0/7/0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | 89 | 89 | 100 | 89 | 89 |

| Zhang [29] | - | - | - | - | - | 92 d | 87 d | - | - | - | - | 93 | 88 | - | 87 | 82 | - |

| Gutschenritter [30] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 70 | 58 | - | 79 | 68 | - |

| Sayan [31] | 35/25/40/0 | 90/10/0/0 | - | 25 | 37 | 96 | - | - | - | - | - | 90 | - | - | 100 | - | - |

| Mifsud_A [32] | 32/23/23/22 | 80/6/14/0 | 21 | 53 | 35 c | 91 | - | - | 83 | - | - | 74 | 60 | - | 78 | - | - |

| Mifsud_B [32] | 16/14/30/40 | 35/14/51/0 | 38 | 84 | 35 c | 79 | - | - | 53 | - | - | 42 | 27 | - | 52 | - | - |

| Hosni [33] | 63/37 a | 73/9/18/0 | 22 | 53 | 82 | 97 d | 96 d | 96 d | 84 | 80 | 77 | - | - | - | 84 | 78 | 75 |

| Haderlein [34] | 24/15/44/14 | 49/22/29/0 | - | 60 | 31 | 86 | 86 | - | - | 62 | - | - | 58 | - | - | 63 | - |

| Kaur [35] | - | - | - | - | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 49 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tam [36] | 31/33/19/15 | 65/14/18/0 | - | - | 50 | 91 d | 88 d | - | 81 | 73 | - | - | - | - | 85 | 77 | 59 |

| Chung [37] | 14/30/16/40 | 51/49 b | - | - | 56 | 97 | 97 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 77 | 76 | - |

| Kim [38] | 17/31/43/9 | 26/74 b | 51 | 34 | 43 | 77 | 63 | 63 | - | - | - | 56 | 47 | 47 | - | 55 | - |

| Al-Mamgani [39] | 27/49/16/8 | 80/6/13/1 | - | - | 58 | 92 | 89 | - | - | - | - | 83 | 83 | - | 72 | 68 | - |

| Pederson [40] | 4/34/25/37 | 25/13/62/0 | - | 54 | 42 | 96 | 96 | - | - | - | - | 62 | 55 | - | 79 | 59 | - |

| Noh [41] | 21/28/35/16 | 81/7/12/0 | 16 | 19 | - | - | 96 | - | - | - | - | - | 74 | - | - | 78 | - |

| Chen [42] | 17/33/27/24 | - | - | 74 | 62 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 81 | 63 | 96 | 81 | 57 |

pTstage, pathologic tumor stage; pNstage, pathologic lymph node stage; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PNI, perineural invasion; f/u, follow-up; mo, months; LRC, locoregional control; DMFS, distant metastases-free survival; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival. a means patients with pT1/2 versus patients with pT3/4. b means patients with pN0 versus patients with pN+. c means the median follow-up period of the entire patients. d reported local control rates.

Six studies included only carcinomas in the parotid gland, followed by carcinomas in the major salivary glands (n = 9), and carcinomas in all salivary glands (n = 11). Most studies included all the histological subtypes. The remaining six studies included only specific histological subtypes: intermediate- to high-grade subtypes (n = 2), all subtypes excluding ACC (n = 2), secretory carcinoma with the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene (n = 1), and salivary duct carcinoma (n = 1). The proportion of high-grade histology was 0–100% (median, 42%). Individual anatomical sites and histological data are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. Facial nerve palsy or dysfunction as the initial symptom was present in 3–8% [18,21,38]. Lymph node dissection (LND) was conducted in 17–94% (median, 46%). Pathological tumor (pT) stage 3 or 4 and pathological LN (pN) involvement were 0–77% (median, 40%), and 0–75% (median, 31%). LVI and PNI were detected in 0–51% (median, 20%) and 10–84% (median, 39%). The definition of close and positive RMs was variable according to the study (Supplementary Table S2), and positive RM was 4–93% (median, 46%). RT was delivered using two-dimensional (2D) RT, three-dimensional conformal RT (3DCRT), and intensity-modulated RT (IMRT). The median RT dose was 64 Gy (range: 56–66 Gy). The proportion of nodal irradiation, including the involved LN and/or elective LN regions, was described in only 11 studies and ranged from 27% to 100% (median, 52%). Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) was applied in 0–100% (median, 4%).

3.3. Survivals

The median follow-up period was 50 months (range: 11–131 months). The median 3-, 5-, and 10-year LRC rates were 91% (range: 77–99%), 89% (range: 63–97%), and 82% (range: 63–96%), respectively. The median 3- and 5-year distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) rates were 83% (range, 53–95%) and 75% (range: 62–80%), respectively. Accordingly, the 3- and 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) rates were 79% (range: 42–100%) and 61% (range: 27–89%). The median 3-, 5-, and 10-year overall survival (OS) rates were 85% (range: 52–100%), 77% (range: 55–89%), and 68% (range: 57–89%), respectively (Table 2). Using the random effects model, the pooled 3-, 5-, and 10-year LRC rates were 92% (95% confidence interval [CI], 89–94%), 89% (95% CI, 86–93%), and 84% (95% CI, 73–92%), respectively. The pooled 3- and 5-year DMFS rates were 81% (95% CI, 76–86%) and 74% (95% CI, 70–79%), respectively, whereas the pooled 3- and 5-year DFS rates were 77% (95% CI, 70–83%) and 67% (95% CI, 60–74%), respectively. The pooled 3-, 5-, and 10-year OS rates were 84% (95% CI, 79–88%), 75% (95% CI, 72–79%), and 68% (95% CI, 62–74%), respectively.

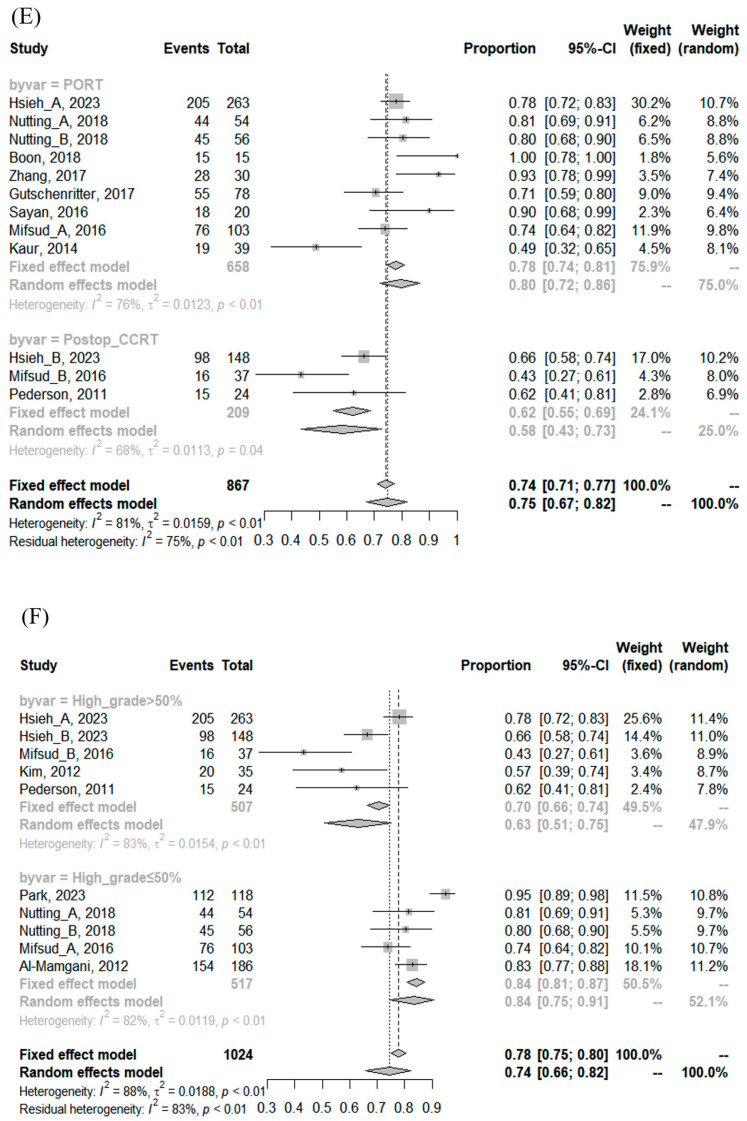

There was significant heterogeneity among the included cohorts for survival estimates (Table 3); however, publication bias was not detected (Supplementary Figure S1). In the subgroup comparison, cohorts with the proportion of a high grade < 50% had significantly better 3- and 10-year LRC, 3-year DFS, and 3- and 5-year DMFS than cohorts with the proportion of a high grade ≥ 50%. Cohorts treated with postoperative CCRT had significantly inferior 3-year DFS and 10-year OS than cohorts treated with PORT alone. No association was found between the RT dose and any survival index, the details of which are summarized in Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Pooled rates of survival.

| Group | Cohorts (n) | Patients (n) | p, Heterogeneity | I2 | Egger’s Test, p | Fixed Event Rate (95% CI) | Random Event Rate (95% CI) | p (between Groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-year LRC | ||||||||

| All | 16 | 1648 | <0.0001 | 71.09% | 0.1752 | 0.93 (0.92–0.94) | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) | |

| Post-op CCRT a | 4 | 229 | 0.2824 | 21.32% | 0.8796 | 0.88 (0.83–0.92) | 0.88 (0.82–0.93) | 0.0875 |

| PORT b | 4 | 416 | 0.9845 | 0% | 0.7215 | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | |

| High grade > 50% c | 6 | 570 | 0.0313 | 59.25% | 0.2016 | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 0.0150 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 5 | 731 | 0.0025 | 75.63% | 0.5867 | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 5 | 682 | 0.0035 | 74.52% | 0.5371 | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | 0.93 (0.88–0.97) | 0.5628 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 10 | 936 | <0.0001 | 73.85% | 0.3466 | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) | |

| 5-year LRC | ||||||||

| All | 14 | 1671 | <0.0001 | 77.99% | 0.3034 | 0.90 (0.89–0.92) | 0.89 (0.86–0.93) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 2 | 172 | 0.0943 | 64.28% | - | 0.86 (0.80–0.91) | 0.89 (0.75–0.98) | 0.6259 |

| PORT | 3 | 368 | 0.1140 | 53.95% | 0.8597 | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | 0.91 (0.85–0.96) | |

| High grade > 50% | 6 | 608 | 0.0003 | 78.75% | 0.7549 | 0.88 (0.85–0.90) | 0.87 (0.80–0.93) | 0.1827 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 4 | 736 | 0.0009 | 81.73% | 0.3854 | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 0.92 (0.87–0.96) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 5 | 790 | <0.0001 | 84.57% | 0.5832 | 0.91 (0.89–0.93) | 0.90 (0.84–0.95) | 0.7043 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 8 | 851 | <0.0001 | 77.55% | 0.6316 | 0.90 (0.87–0.92) | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) | |

| 10-year LRC | ||||||||

| All | 5 | 810 | <0.0001 | 91.93% | 0.1546 | 0.89 (0.86–0.91) | 0.84 (0.73–0.92) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 1 | 148 | - | - | - | 0.82 (0.75–0.88) | 0.82 (0.75–0.88) | 0.3608 |

| PORT | 1 | 263 | - | - | - | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | |

| High grade > 50% | 3 | 446 | 0.0130 | 76.96% | 0.0151 | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) | 0.80 (0.70–0.88) | <0.0001 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 1 | 304 | - | - | - | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 2 | 452 | <0.0001 | 95.66% | - | 0.92 (0.90–0.95) | 0.90 (0.72–0.99) | 0.2421 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 3 | 358 | 0.0131 | 76.92% | 0.3025 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | 0.79 (0.66–0.89) | |

| 3-year DFS | ||||||||

| All | 16 | 1266 | <0.0001 | 85.97% | 0.6650 | 0.78 (0.76–0.80) | 0.77 (0.70–0.83) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 3 | 209 | 0.0421 | 68.44% | 0.5343 | 0.62 (0.55–0.69) | 0.58 (0.43–0.73) | 0.0090 |

| PORT | 9 | 658 | <0.0001 | 76.08% | 0.4283 | 0.78 (0.74–0.81) | 0.80 (0.72–0.86) | |

| High grade > 50% | 5 | 507 | <0.0001 | 83.26% | 0.0811 | 0.70 (0.66–0.74) | 0.63 (0.51–0.75) | 0.0054 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 5 | 517 | 0.0001 | 82.42% | 0.7517 | 0.84 (0.81–0.87) | 0.84 (0.75–0.91) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 6 | 483 | 0.0002 | 79.55% | 0.6255 | 0.78 (0.74–0.82) | 0.80 (0.70–0.88) | 0.4020 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 8 | 675 | <0.0001 | 90.67% | 0.3045 | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | 0.73 (0.60–0.84) | |

| 5-year DFS | ||||||||

| All | 17 | 1672 | <0.0001 | 87.62% | 0.1034 | 0.71 (0.68–0.73) | 0.67 (0.60–0.74) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 3 | 209 | 0.0022 | 83.69% | 0.5542 | 0.53 (0.46–0.59) | 0.47 (0.27–0.67) | 0.0522 |

| PORT | 7 | 622 | 0.0008 | 73.74% | 0.8001 | 0.68 (0.65–0.72) | 0.69 (0.61–0.77) | |

| High grade > 50% | 7 | 645 | <0.0001 | 84.82% | 0.0866 | 0.64 (0.60–0.67) | 0.58 (0.46–0.68) | 0.0780 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 4 | 535 | <0.0001 | 91.90% | 0.4448 | 0.75 (0.71–0.78) | 0.73 (0.59–0.85) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 5 | 501 | <0.0001 | 88.32% | 0.8474 | 0.70 (0.66–0.74) | 0.69 (0.55–0.81) | 0.6700 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 10 | 1063 | <0.0001 | 89.39% | 0.0252 | 0.71 (0.68–0.74) | 0.65 (0.55–0.74) | |

| 10-year DFS | ||||||||

| All | 6 | 772 | 0.0307 | 59.39% | 0.8729 | 0.61 (0.58–0.65) | 0.61 (0.55–0.67) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 1 | 148 | - | - | - | 0.53 (0.45–0.61) | 0.53 (0.45–0.61) | 0.1010 |

| PORT | 2 | 278 | 0.0655 | 70.53% | - | 0.66 (0.60–0.71) | 0.73 (0.50–0.91) | |

| High grade > 50% | 3 | 446 | 0.0379 | 69.44% | 0.4465 | 0.59 (0.54–0.64) | 0.57 (0.47–0.66) | - |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | ||

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 2 | 163 | 0.0080 | 85.78% | - | 0.56 (0.48–0.64) | 0.69 (0.34–0.95) | 0.7471 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 4 | 609 | 0.3888 | 0.61% | 0.2291 | 0.63 (0.59–0.67) | 0.63 (0.59–0.67) | |

| 3-year OS | ||||||||

| All | 18 | 2284 | <0.0001 | 84.23% | 0.8229 | 0.84 (0.83–0.86) | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 3 | 209 | 0.0038 | 82.04% | 0.6017 | 0.75 (0.69–0.81) | 0.71 (0.52–0.87) | 0.0755 |

| PORT | 8 | 619 | 0.0070 | 63.94% | 0.4503 | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | 0.87 (0.81–0.92) | |

| High grade > 50% | 4 | 472 | <0.0001 | 87.60% | 0.2295 | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) | 0.77 (0.63–0.88) | 0.5862 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 6 | 1121 | 0.0481 | 55.24% | 0.8811 | 0.80 (0.78–0.83) | 0.80 (0.76–0.84) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 7 | 787 | 0.0071 | 66.03% | 0.4498 | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | 0.82 (0.76–0.87) | 0.4812 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 8 | 971 | <0.0001 | 89.66% | 0.3286 | 0.88 (0.86–0.90) | 0.85 (0.77–0.92) | |

| 5-year OS | ||||||||

| All | 17 | 2315 | 0.0001 | 64.47% | 0.0875 | 0.77 (0.75–0.79) | 0.75 (0.72–0.79) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 2 | 172 | 0.2185 | 33.97% | - | 0.70 (0.62–0.76) | 0.68 (0.56–0.78) | 0.0903 |

| PORT | 5 | 461 | 0.2404 | 27.17% | 0.9974 | 0.79 (0.75–0.82) | 0.78 (0.73–0.83) | |

| High grade > 50% | 6 | 608 | 0.0021 | 73.40% | 0.0424 | 0.74 (0.70–0.78) | 0.70 (0.62–0.78) | 0.2397 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 4 | 1036 | 0.0030 | 78.45% | 0.1743 | 0.77 (0.75–0.80) | 0.76 (0.70–0.81) | |

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 6 | 805 | 0.0615 | 52.52% | 0.6291 | 0.74 (0.70–0.77) | 0.73 (0.68–0.78) | 0.3252 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 8 | 984 | 0.0063 | 64.42% | 0.1360 | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | 0.76 (0.71–0.81) | |

| 10-year OS | ||||||||

| All | 8 | 1659 | <0.0001 | 85.03% | 0.3694 | 0.67 (0.64–0.69) | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | |

| Post-op CCRT | 1 | 148 | - | - | - | 0.61 (0.53–0.69) | 0.61 (0.53–0.69) | 0.0453 |

| PORT | 2 | 278 | 0.2472 | 25.32% | - | 0.74 (0.68–0.79) | 0.75 (0.65–0.85) | |

| High grade > 50% | 2 | 411 | 0.0257 | 79.91% | - | 0.68 (0.64–0.73) | 0.67 (0.56–0.77) | 0.8249 |

| High grade ≤ 50% | 2 | 722 | 0.0005 | 91.67% | 0.68 (0.65–0.72) | 0.69 (0.57–0.80) | ||

| mRT dose > 64 Gy | 3 | 467 | 0.0062 | 80.33% | 0.9409 | 0.72 (0.67–0.76) | 0.72 (0.60–0.83) | 0.6456 |

| mRT dose ≤ 64 Gy | 4 | 774 | <0.0001 | 89.58% | 0.4103 | 0.65 (0.62–0.69) | 0.68 (0.57–0.78) |

n, number; CI, confidence interval; LRC, locoregional control; post-op CCRT, postoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy; PORT, postoperative radiotherapy; mRT dose, median radiotherapy dose; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival. a includes cohorts with all patients receiving post-op CCRT. b includes cohorts with all patients receiving PORT alone. Cohorts with mixed patients receiving post-op CCRT or PORT were excluded. c means that the proportion of patients with a high grade is greater than 50% among the entire patients.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of (A) 3-year locoregional control (LRC), (B) 5-year LRC, (C) 3-year disease-free survival (DFS), (D) 5-year DFS, (E) 3-year DFS between cohorts treated with postoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy (Post-op_CCRT) versus cohorts with postoperative radiotherapy alone (PORT), and (F) 3-year DFS between cohorts with the proportion of a high grade ≥ 50% versus cohorts with the proportion of a high grade < 50%.

3.4. Late Toxicities

The overall incidence and evaluated types of late toxicities were variable among the included studies, as shown in Table 4. The pooled rates assessed using the random-effects model for the overall incidences of xerostomia, hearing impairment, and osteoradionecrosis were 37% (95% CI, 11–68%), 25% (95% CI, 7–49%), and 1% (95% CI, 1–2%), respectively. Severe late toxicity ≥ grade 3 occurred in 0–34%, and the pooled rate was 7% (95% CI, 3–14%), respectively (Supplementary Figure S2).

Table 4.

Late toxicities after surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy for salivary gland cancer.

| Author | Criteria | Overall Toxicity (%) | Severe Toxicity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Park [18] | CTCAEv5.0 | Hearing loss of Gr3 (1) | Gr3 (1) |

| Duru Birgi [19] | CTCAEv4.0 | Trigeminal nerve toxicity of Gr1 (22) and Gr2 (39) | No ≥ Gr3 toxicity |

| Zang [21] | - | Xerostomia (30); Hearing impairment (28); Taste abnormalities (25); Paresthesia (23); Fibrosis of the skin (18); Trismus (10); ORN (3) | Gr3 (3) |

| Nutting_A [24] | CTCAEv3.0 | Hearing toxicity of Gr1 (31), Gr2 (29), Gr3 (12), and Gr4 (2); OE of Gr1 (26), Gr2 (6), and Gr3 (2); OM of Gr1 (28), Gr2 (4), and Gr3 (2); Tinnitus of Gr2 (56) and Gr3 (2); Otalgia of Gr1 (24), Gr2 (10), and Gr3 (2); Skin pigmentation of Gr1 (49) and Gr 2 (6); Skin atrophy of Gr1 (48) and Gr2 (2); Skin fibrosis of Gr1 (52) and Gr2 (10); Functional mucous membrane toxicity of Gr1(20), Gr2 (8), and Gr3 (2); Clinical exam-mucous membrane toxicity of Gr1 (24) and Gr2 (4); Dry mouth of Gr1 (58), Gr2 (22), and Gr3 (4); Salivary gland changes of Gr1 (54) and Gr2 (20); ORN of Gr1 (2); Trismus of Gr1 (30) and Gr2 (6); Fatigue of Gr1 (26), Gr2 (10), and Gr3 (6) | Gr3 (32)/Gr4 (2) |

| Nutting_B [24] | CTCAEv3.0 | Hearing toxicity of Gr1 (37), Gr2 (20), Gr3 (9), and Gr4 (7); OE of Gr1 (30) and Gr2 (7); OM of Gr1 (30) and Gr2 (4); Tinnitus of Gr1 (4), Gr2 (37), and Gr3 (7); Otalgia of Gr1 (28) and Gr2 (2); Skin pigmentation of Gr1 (43) and Gr 2 (4); Skin atrophy of Gr1 (44) and Gr2 (2); Skin fibrosis of Gr1 (56) and Gr2 (4); Functional mucous membrane toxicity of Gr1 (33) and Gr2 (9); Clinical exam-mucous membrane toxicity of Gr1 (24) and Gr2 (4); Dry mouth of Gr1 (72), Gr2 (20), and Gr3 (2)/Salivary gland changes of Gr1 (69), Gr2 (7), and Gr3 (2); ORN of Gr1 (2); Trismus of Gr1 (43) and Gr2 (6); Fatigue of Gr1 (40) and Gr2 (8) | Gr3 (20)/Gr4 (7) |

| Gebhardt [27] | CTCAEv4.0 | Gr1 (52) and Gr2 (13) | No ≥ Gr3 toxicity |

| Sayan [31] | RTOG/EORTC | Xerostomia of Gr2 (25); Hearing loss (5) | Gr3 (5) |

| Hosni [33] | RTOG | ORN of Gr3 (1); Neck fibrosis of Gr3 (1); Trismus of Gr3 (0.3); Dysphagia of Gr3 (0.3) | Gr3 (3) |

| Tam [36] | CTCAEv4.0 | Xerostomia of Gr 1–2 (54) and Gr 3 (1); Hearing loss of Gr 1–3 (19); PEG replacement (2); Radiation necrosis of Gr1 (1) | Gr3 (19) |

| Chung [37] | CTCAEv4.0 | Hypothyroidism of Gr2, Xerostomia of Gr2, Trismus of Gr2; Fibrosis of Gr3 in 1 patient (3) | Gr3 (3) |

| Al-Mamgani [39] | CTCAEv3.0 | Overall toxicities ≥ Gr2 (8); ORN of Gr3 (2); Hearing loss requiring hearing aid (6); Dysphagia and xerostomia of Gr2 (2); Subcutaneous toxicities of Gr2 (2) | Gr3 (9) |

| Pederson [40] | CTCAEv3.0 | Xerostomia (21)/Esophageal stricture requiring dilatation (4)/TMJ syndrome (4)/Feeding tubes (13) | Gr3 (21) |

CTCAE, the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; RTOG/EORTC, Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; ORN, osteoradionecrosis; OE, otitis externa; OM, otitis media; TMJ, temporomandibular joint; Gr, grade.

4. Discussion

The principal treatment for SGC is surgical resection with adequate free margins. PORT is considered for patients with adverse prognostic factors; however, its survival benefit is unclear. Gutschenritter et al. [30] reported no statistically significant difference in survival between patients who underwent surgery alone and those who underwent surgery followed by PORT for SGC: 72% vs. 58% at 5-year DFS rates; and 88% vs. 68% at 5-year OS rates, respectively. Noh et al. [41] showed a similar 5-year LCR between surgery alone and PORT (100% vs. 96%) for major SGC, despite PORT being administered only to patients with high-risk factors. However, the 5-year DFS and OS rates were lower in the PORT (74% and 78%, respectively) than in the surgery-alone (95% and 100%, respectively) group. A recent study on parotid gland cancer reported that PORT was associated with a significant improvement in the 5-year LRC (p = 0.005) and DFS (p = 0.009) compared with surgery alone [18]. To overcome the limitations of these retrospective studies with a small number of patients and an imbalance in prognostic factors between the treatment groups, several studies using the National Cancer Database (NCDB) have been published. A study of 4068 patients with SGC with pT1–4NX–1M0 high-grade tumors, pT3–4NX–0M0, or pT1–4N1M0 low-grade tumors showed a statistically improved OS with PORT, with minimal absolute benefit (56% vs. 51% at 5 years) [43]. Another two studies (4145 patients with SGC who were treated with primary resection and LND [44] and 7342 patients with SGC who had MEC, acinic cell carcinoma, ACC, adenocarcinoma, or Ca ex PA [45]) also showed better OS with PORT. Collectively, the three NCDB studies enrolled almost all contemporary patient cohorts treated between 2004 and the early 2010s.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on the treatment outcomes of patients with SGC who underwent surgery followed by PORT. Compared with the abovementioned studies, our pooled cohort included more recent patients who were treated up to 2020, implying a higher proportion of more advanced RT techniques and a more meticulous histological classification being applied. The pooled 5-year LRC, DFS, and OS rates were 89% (95% CI, 86–93%), 67% (95% CI, 60–74%), and 75% (95% CI, 72–79%), respectively. The favorable survival compared to that reported in previously published studies supports the efficacy of PORT as a local modality. Considering that the LRC, DMFS, and DFS continue to decrease, however, further clinical trials are warranted to improve both locoregional and distant tumor control.

In the subgroup analysis, cohorts with a proportion of a high grade ≥ 50% had statistically worse 3- and 10-year LRC, 3-year DFS, and 3- and 5-year DMFS. A high grade is one of the most important risk factors for the recurrence of SGC, and all guidelines recommend PORT for patients with high-grade tumors [6,7,8,9]. On the other hand, the necessity of PORT is controversial in cases of low- and intermediate-grade tumors. One NCDB study of 744 patients with intermediate-grade, early T-stage, LN-negative parotid cancer reported that PORT significantly and independently improved survival only in patients with positive RM [46]. A Canadian-led multicenter retrospective study of 621 patients with low- or intermediate-grade major SGC estimated that the marginal probability of locoregional recurrence (LRR) within 10 years was 15.4% without PORT and 8.8% with PORT on the multivariable model [47]. The authors suggested that PORT may reduce LRR in some patients with low- and intermediate-grade SGC with advanced pT stage, LVI, and RM (+). The study, using the Taiwan Cancer Registry and National Health Insurance Research Database, analyzed 655 patients with early-stage major SGC [48]. No significant differences were noted in the LRR and disease-specific survival between patients who received PORT and those who did not. Although RM (+) patients had a higher LRR, the stratified analysis indicated that the use of PORT had no protective effects. The status of RM is generally considered a major determinant in applying PORT for low- and intermediate-grade SGC; however, the definition of close and positive RM varies among studies, as shown in Supplementary Table S2. This discrepancy might have caused the conflicting results of PORT in terms of survival. Subgroup analysis on RM in the current meta-analysis was challenging because of the lack of individual patient data and variable definitions of RM. Efforts should be made to establish a uniform definition of the proper RM for SGC and assess whether the status of RM truly affects survival in low-to intermediate-grade SGC.

Compared with good LCR achieved by surgery followed by PORT, suboptimal survival and DM-dominant recurrent patterns of SGC require the development of several intensified treatment strategies, such as postoperative CCRT. Notwithstanding, this meta-analysis showed that postoperative CCRT led to significantly inferior 3-year DFS and 10-year OS rates to those of PORT. Among the 26 studies, three retrospective studies compared PORT with postoperative CCRT, and the cohorts receiving postoperative CCRT apparently harbored more adverse prognostic factors than those receiving PORT, with statistical significance [20,31,32]. Overall, no statistically significant survival benefit existed from postoperative CCRT, with only one study showing improved long-term OS and PFS in SGC patients with LN metastases and superior LRC in patients with R2 resection or ACC [20]. The NCDB studies failed to show improved outcomes with the addition of chemotherapy to PORT in SGC patients [49,50]. Another NCDB study reported that postoperative CCRT was associated with increased mortality on both multivariable and propensity score-adjusted analyses (hazard ratio [HR]:1.39; 95% CI: 1.07–1.79 and HR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.14–1.94, respectively) [51]. Therefore, the current level of evidence on postoperative CCRT is still low in unselected patients with SGC, and this treatment strategy is not recommended outside clinical studies. The ongoing phase III RTOG 1008 study (NCT01220583), which compares PORT with postoperative CCRT using weekly cisplatin in patients with high-risk SGC after surgery, might provide some answers.

This meta-analysis includes studies that used megavoltage equipment and reflects the treatment outcomes of modern RT techniques for SGC. Because the theoretical advantages of IMRT dose distributions over 2DRT and 3DCRT are generally accepted, IMRT has been routinely used throughout all tumor sites, and guidelines for SGC also recommend the use of IMRT [6,7,52,53]. In the current meta-analysis, the pooled rate for severe toxicity ≥ grade 3 was 7% (95% CI, 3–14%), indicating that PORT can be used as a local modality with an acceptable level of safety. Although IMRT has changed the practice of RT, it is unclear whether its use provides a clinically relevant advantage in SGC [54]. The overall incidence of late toxicity varied among the included cohorts, as presented in Table 4. Among these, two studies focused on RT-related toxicity in SGC. A phase 3 trial comparing 3DCRT with cochlear-sparing IMRT for parotid gland cancer showed no significant differences in hearing loss or other secondary endpoints, including patient-reported hearing outcomes, although the median dose to the ipsilateral cochlea was significantly reduced (56 Gy with 3DCRT vs. 36 Gy with IMRT, p < 0.0001) [24]. The second was a retrospective study that evaluated trigeminal nerve toxicity after IMRT for resected parotid gland cancer [19]. Grades 1 and 2 of trigeminal nerve toxicities occurred in 22% and 39% of patients, respectively, which were higher than the incidence of cranial nerve toxicity of 4–31% observed in head and neck studies treated with definitive RT [55,56,57]. The authors suggested that surgical interventions could potentially induce alterations in the postoperative tissues, leading to increased susceptibility. Therefore, further observations are required to evaluate the long-term safety of IMRT for SGC.

This study has some limitations. First, prospective or retrospective studies were included, except for one phase 3 study that focused on RT-related toxicity. The heterogeneity of observational studies and selection bias may have affected the pooled analysis [58]. In addition, there was a time interval between the literature search and publication, and this might give rise to publication bias. Considering that the median time from the literature search to publication was 8 months, and the time interval of recent meta-analyses was not significantly different, our systematic review provides timely, up-to-date evidence [13,59]. Second, 26 studies published between 2007 and 2023 were included in this analysis. The WHO classification system for SGC was updated until 2022, and the classification of histological subtypes changed several times during this period. Boon et al. [28] found that secretory carcinoma characterized by the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene, a new subtype of SGC in 2010, was previously diagnosed as acinic cell carcinoma, polymorphous adenocarcinoma, or adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified. However, this effect may have been minimized, because the current study included all the histological subtypes. Lastly, we included the use of megavoltage equipment and excluded studies treated with 60Co gamma rays. In addition, we did not permit duplicate patient data and selected the most recent study from one institution. This might reduce the number of late toxicities, and long-term outcomes and toxicities were not complete in some studies. Among the twenty-six studies, nine studies reported 10-year survival outcomes, and eleven evaluated late treatment-related toxicities. Further studies are needed to validate the long-term efficacy and safety of PORT for SGC.

5. Conclusions

The current systematic review and meta-analysis comprehensively demonstrated the short- and long-term survival and toxicities of PORT as a local treatment modality for SGC. High-grade histology has been confirmed to be a strong indicator of the utilization of PORT, whereas the value of PORT in low- to intermediate-grade tumors is still questionable and needs further assessment. Considering the suboptimal DFS and DM-dominant recurrent patterns, an intensified treatment strategy would be needed. However, concurrent chemotherapy accompanied by PORT may not be a good option as an intensified modality based on the pooled data. Further prospective investigations are warranted.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers16132375/s1, Table S1. Search strategy and results. Table S2. Tumor details for salivary gland carcinoma treated with surgery followed by postoperative radiotherapy. Table S3. Pooled rates of distant metastases free survival (DMFS). Figure S1. Funnel plots for survivals. Figure S2. Forrest plots of toxicities

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.H.B. and J.Y. (Junlin Yi); data curation: S.H.B.; formal analysis: S.H.B., J.W. and J.E.M.; funding acquisition: S.H.B.; investigation: S.H.B., X.G. and J.Y. (Jiaqi Yu); methodology: S.H.B. and J.W.; software: S.H.B., X.G. and J.Y. (Jiaqi Yu); validation: S.H.B.; visualization: S.H.B.; writing—original draft: S.H.B. and J.W.; writing—review and editing: S.H.B. and J.Y. (Junlin Yi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund. No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Skalova A., Hyrcza M.D., Leivo I. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Salivary Glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2022;16:40–53. doi: 10.1007/s12105-022-01420-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young A., Okuyemi O.T. Statpearls. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2023. Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dos Santos E.S., Rodrigues-Fernandes C.I., Speight P.M., Khurram S.A., Alsanie I., Normando A.G.C., Prado-Ribeiro A.C., Brandao T.B., Kowalski L.P., Guerra E.N.S., et al. Impact of Tumor Site on the Prognosis of Salivary Gland Neoplasms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021;162:103352. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson D.J., Slevin N.J., Mendenhall W.M. Indications for Salivary Gland Radiotherapy. Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;78:141–147. doi: 10.1159/000442134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiro R.H. Management of Malignant Tumors of the Salivary Glands. Oncology. 1998;12:671–680. Discussion 683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geiger J.L., Ismaila N., Beadle B., Caudell J.J., Chau N., Deschler D., Glastonbury C., Kaufman M., Lamarre E., Lau H.Y., et al. Management of Salivary Gland Malignancy: Asco Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021;39:1909–1941. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Herpen C., Poorten V.V., Skalova A., Terhaard C., Maroldi R., van Engen A., Baujat B., Locati L.D., Jensen A.D., Smeele L., et al. Salivary Gland Cancer: Esmo-European Reference Network on Rare Adult Solid Cancers (Euracan) Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. ESMO Open. 2022;7:100602. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thariat J., Ferrand F.R., Fakhry N., Even C., Vergez S., Chabrillac E., Sarradin V., Digue L., Troussier I., Bensadoun R.J. Radiotherapy for Salivary Gland Cancer: Refcor Recommendations by the Formal Consensus Method. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2023;23:S1879–S7296. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2023.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Head and Neck Cancers Version 2. 2024. [(accessed on 21 June 2024)]. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_Gls/Pdf/Head-and-Neck.Pdf.

- 10.Locati L.D., Ferrarotto R., Licitra L., Benazzo M., Preda L., Farina D., Gatta G., Lombardi D., Nicolai P., Poorten V.V., et al. Current Management and Future Challenges in Salivary Glands Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023;13:1264287. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1264287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., Shamseer L., Tetzlaff J.M., Akl E.A., Brennan S.E., et al. The Prisma 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pieper D., Rombey T. Where to Prospectively Register a Systematic Review. Syst. Rev. 2022;11:8. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01877-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen M., Fonnes S., Andresen K., Rosenberg J. Most Published Meta-Analyses Were Made Available within Two Years of Protocol Registration. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2021;44:101342. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2021.101342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stang A. Critical Evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the Assessment of the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raudenbush S.W. Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY, USA: 2009. Analyzing Effect Sizes: Random-Effects Models; pp. 295–315. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan W., Ou X., Shen C., Hu C. A Nomogram Involving Immune-Inflammation Index for Predicting Distant Metastasis-Free Survival of Major Salivary Gland Carcinoma Following Postoperative Radiotherapy. Cancer Med. 2023;12:2772–2781. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J.B., Wu H.G., Kim J.H., Lee J.H., Ahn S.H., Chung E.J., Eom K.Y., Jeong W.J., Kwon T.K., Kim S., et al. Adjuvant Radiotherapy in Node-Negative Salivary Malignancies of the Parotid Gland: A Multi-Institutional Analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 2023;183:109554. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duru Birgi S., Akyurek S., Birgi E., Arslan Y., Gumustepe E., Bakirarar B., Gokce S.C. Dosimetric Investigation of Radiation-Induced Trigeminal Nerve Toxicity in Parotid Tumor Patients. Head Neck. 2023;45:2907–2914. doi: 10.1002/hed.27524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh R.C., Chou Y.C., Hung C.Y., Lee L.Y., Venkatesulu B.P., Huang S.F., Liao C.T., Cheng N.M., Wang H.M., Wu C.E., et al. A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis of Patients with Salivary Gland Carcinoma Treated with Postoperative Radiotherapy Alone or Chemoradiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2023;188:109891. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zang S., Chen M., Huang H., Zhu X., Li X., Yan D., Yan S. Oncological Outcomes of Patients with Salivary Gland Cancer Treated with Surgery and Postoperative Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022;12:2841–2854. doi: 10.21037/qims-21-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco I.I., Shin K.Y., Jo V., Hanna G.J., Schoenfeld J.D., Tishler R.B., Milligan M.G., Rettig E.M., Margalit D.N. Identification of Salivary Gland Tumors (Sgt) at Risk for Local or Distant Recurrence after Postoperative Radiation Therapy (Port) with or without Systemic Therapy (St) Using Clinical Risk Grouping. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021;111:e414. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.07.1189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dou S., Wang X., Li R., Wu S., Ruan M., Yang W., Zhu G. Prospective Phase Ii Study of Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in High-Risk Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019;105:S214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nutting C.M., Morden J.P., Beasley M., Bhide S., Cook A., De Winton E., Emson M., Evans M., Fresco L., Gollins S., et al. Results of a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial of Cochlear-Sparing Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy Versus Conventional Radiotherapy in Patients with Parotid Cancer (Costar; Cruk/08/004) Eur. J. Cancer. 2018;103:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishikado A., Kawata R., Haginomori S.I., Terada T., Higashino M., Kurisu Y., Hirose Y. A Clinicopathological Study of Parotid Carcinoma: 18-Year Review of 171 Patients at a Single Institution. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;23:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-1266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R., Dou S., Ruan M., Zhang C., Zhu G. A Feasibility and Safety Study of Concurrent Chemotherapy Based on Genetic Testing in Patients with High-Risk Salivary Gland Tumors: Preliminary Results. Medicine. 2018;97:e0564. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebhardt B.J., Ohr J.P., Ferris R.L., Duvvuri U., Kim S., Johnson J.T., Heron D.E., Clump D.A., 2nd Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in the Adjuvant Treatment of High-Risk Primary Salivary Gland Malignancies. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018;41:888–893. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boon E., Valstar M.H., van der Graaf W.T.A., Bloemena E., Willems S.M., Meeuwis C.A., Slootweg P.J., Smit L.A., Merkx M.A.W., Takes R.P., et al. Clinicopathological Characteristics and Outcome of 31 Patients with Etv6-Ntrk3 Fusion Gene Confirmed (Mammary Analogue) Secretory Carcinoma of Salivary Glands. Oral. Oncol. 2018;82:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X., Zeng X., Lan X., Huang J., Luo K., Tian K., Wu X., Xiao F., Li S. Reoperation Following the Use of Non-Standardized Procedures for Malignant Parotid Tumors. Oncol. Lett. 2017;14:6701–6707. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutschenritter T., Machiorlatti M., Vesely S., Ahmad B., Razaq W., Razaq M. Outcomes and Prognostic Factors of Resected Salivary Gland Malignancies: Examining a Single Institution’s 12-Year Experience. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:5019–5025. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sayan M., Vempati P., Miles B., Teng M., Genden E., Demicco E.G., Misiukiewicz K., Posner M., Gupta V., Bakst R.L. Adjuvant Therapy for Salivary Gland Carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:4165–4170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mifsud M.J., Tanvetyanon T., McCaffrey J.C., Otto K.J., Padhya T.A., Kish J., Trotti A.M., Harrison L.B., Caudell J.J. Adjuvant Radiotherapy Versus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy for the Management of High-Risk Salivary Gland Carcinomas. Head Neck. 2016;38:1628–1633. doi: 10.1002/hed.24484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosni A., Huang S.H., Goldstein D., Xu W., Chan B., Hansen A., Weinreb I., Bratman S.V., Cho J., Giuliani M., et al. Outcomes and Prognostic Factors for Major Salivary Gland Carcinoma Following Postoperative Radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2016;54:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haderlein M., Scherl C., Semrau S., Lettmaier S., Uter W., Neukam F.W., Iro H., Agaimy A., Fietkau R. High-Grade Histology as Predictor of Early Distant Metastases and Decreased Disease-Free Survival in Salivary Gland Cancer Irrespective of Tumor Subtype. Head Neck. 2016;38((Suppl. S1)):E2041–E2048. doi: 10.1002/hed.24375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaur J., Goyal S., Muzumder S., Bhasker S., Mohanti B.K., Rath G.K. Outcome of Surgery and Post-Operative Radiotherapy for Major Salivary Gland Carcinoma: Ten Year Experience from a Single Institute. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8259–8263. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.19.8259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tam M., Riaz N., Salgado L.R., Spratt D.E., Katsoulakis E., Ho A., Morris L.G.T., Wong R., Wolden S., Rao S., et al. Distant Metastasis Is a Critical Mode of Failure for Patients with Localized Major Salivary Gland Tumors Treated with Surgery and Radiation. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2013;2:285–291. doi: 10.1007/s13566-013-0107-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung M.P., Tang C., Chan C., Hara W.Y., Loo B.W., Jr., Kaplan M.J., Fischbein N., Le Q.T., Chang D.T. Radiotherapy for Nonadenoid Cystic Carcinomas of Major Salivary Glands. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2013;34:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J.Y., Lee S., Cho K.J., Kim S.Y., Nam S.Y., Choi S.H., Roh J.L., Choi E.K., Kim J.H., Song S.Y., et al. Treatment Results of Post-Operative Radiotherapy in Patients with Salivary Duct Carcinoma of the Major Salivary Glands. Br. J. Radiol. 2012;85:e947–e952. doi: 10.1259/bjr/21574486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Mamgani A., van Rooij P., Verduijn G.M., Meeuwis C.A., Levendag P.C. Long-Term Outcomes and Quality of Life of 186 Patients with Primary Parotid Carcinoma Treated with Surgery and Radiotherapy at the Daniel Den Hoed Cancer Center. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012;84:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pederson A.W., Salama J.K., Haraf D.J., Witt M.E., Stenson K.M., Portugal L., Seiwert T., Villaflor V.M., Cohen E.E., Vokes E.E., et al. Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Locoregionally Advanced and High-Risk Salivary Gland Malignancies. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noh J.M., Ahn Y.C., Nam H., Park W., Baek C.H., Son Y.I., Jeong H.S. Treatment Results of Major Salivary Gland Cancer by Surgery with or without Postoperative Radiation Therapy. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;3:96–101. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2010.3.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen A.M., Garcia J., Lee N.Y., Bucci M.K., Eisele D.W. Patterns of Nodal Relapse after Surgery and Postoperative Radiation Therapy for Carcinomas of the Major and Minor Salivary Glands: What Is the Role of Elective Neck Irradiation? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007;67:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safdieh J., Givi B., Osborn V., Lederman A., Schwartz D., Schreiber D. Impact of Adjuvant Radiotherapy for Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017;157:988–994. doi: 10.1177/0194599817717661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aro K., Ho A.S., Luu M., Kim S., Tighiouart M., Yoshida E.J., Clair J.M.-S., Shiao S.L., Leivo I., Zumsteg Z.S. Survival Impact of Adjuvant Therapy in Salivary Gland Cancers Following Resection and Neck Dissection. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019;160:1048–1057. doi: 10.1177/0194599819827851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrell J.K., Mace J.C., Clayburgh D. Contemporary Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Salivary Gland Carcinoma: A National Cancer Database Review. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:1135–1146. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.North L., Stadler M., Massey B., Campbell B., Shukla M., Awan M., Schultz C.J., Shreenivas A., Wong S., Graboyes E., et al. Intermediate-Grade Carcinoma of the Parotid and the Impact of Adjuvant Radiation. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2019;40:102282. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.102282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morand G.B., Eskander A., Fu R., de Almeida J., Goldstein D., Noroozi H., Hosni A., Seikaly H., Tabet P., Pyne J.M., et al. The Protective Role of Postoperative Radiation Therapy in Low and Intermediate Grade Major Salivary Gland Malignancies: A Study of the Canadian Head and Neck Collaborative Research Initiative. Cancer. 2023;129:3263–3274. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hong W.J., Chang S.L., Tsai C.J., Wu H.C., Chen Y.C., Yang C.C., Ho C.H. The Effect of Adjuvant Radiotherapy on Clinical Outcomes in Early Major Salivary Gland Cancer. Head Neck. 2022;44:2865–2874. doi: 10.1002/hed.27203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amini A., Waxweiler T.V., Brower J.V., Jones B.L., McDermott J.D., Raben D., Ghosh D., Bowles D.W., Karam S.D. Association of Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy vs. Radiotherapy Alone with Survival in Patients with Resected Major Salivary Gland Carcinoma: Data from the National Cancer Data Base. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:1100–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheraghlou S., Kuo P., Mehra S., Agogo G.O., Bhatia A., Husain Z.A., Yarbrough W.G., Burtness B.A., Judson B.L. Adjuvant Therapy in Major Salivary Gland Cancers: Analysis of 8580 Patients in the National Cancer Database. Head Neck. 2018;40:1343–1355. doi: 10.1002/hed.24984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanvetyanon T., Fisher K., Caudell J., Otto K., Padhya T., Trotti A. Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Versus with Radiotherapy Alone for Locally Advanced Salivary Gland Carcinoma among Older Patients. Head Neck. 2016;38:863–870. doi: 10.1002/hed.24172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dennis K., Linden K., Gaudet M. A Shift from Simple to Sophisticated: Using Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy in Conventional Nonstereotactic Palliative Radiotherapy. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care. 2023;17:70–76. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim E., Jang W.I., Yang K., Kim M.S., Yoo H.J., Paik E.K., Kim H., Yoon J. Clinical Utilization of Radiation Therapy in Korea between 2017 and 2019. Radiat. Oncol. J. 2022;40:251–259. doi: 10.3857/roj.2022.00500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jang W.I., Jo S., Moon J.E., Bae S.H., Park H.C. The Current Evidence of Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2023;15:4914. doi: 10.3390/cancers15204914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kong L., Lu J.J., Liss A.L., Hu C., Guo X., Wu Y., Zhang Y. Radiation-Induced Cranial Nerve Palsy: A Cross-Sectional Study of Nasopharyngeal Cancer Patients after Definitive Radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011;79:1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rong X., Tang Y., Chen M., Lu K., Peng Y. Radiation-Induced Cranial Neuropathy in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. A Follow-up Study. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2012;188:282–286. doi: 10.1007/s00066-011-0047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luk Y.S., Shum J.S., Sze H.C., Chan L.L., Ng W.T., Lee A.W. Predictive Factors and Radiological Features of Radiation-Induced Cranial Nerve Palsy in Patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma following Radical Radiotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2013;49:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blettner M., Sauerbrei W., Schlehofer B., Scheuchenpflug T., Friedenreich C. Traditional Reviews, Meta-Analyses and Pooled Analyses in Epidemiology. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1999;28:1–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beller E.M., Chen J.K., Wang U.L., Glasziou P.P. Are Systematic Reviews up-to-Date at the Time of Publication? Syst. Rev. 2013;2:36. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.