Abstract

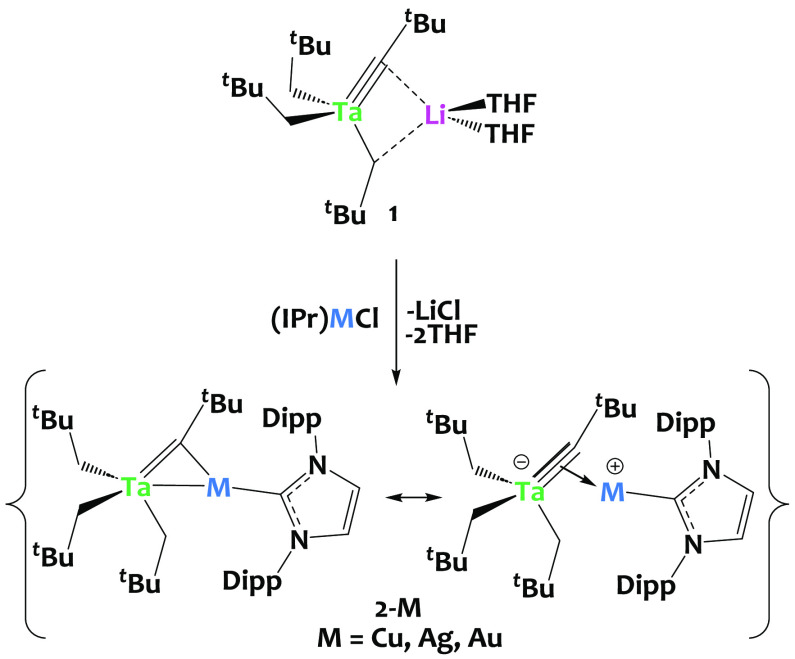

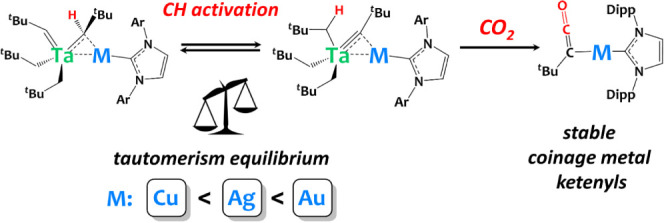

A salt metathesis synthetic strategy is used to access rare tantalum/coinage metal (Cu, Ag, Au) heterobimetallic complexes. Specifically, complex [Li(THF)2][Ta(CtBu)(CH2tBu)3], 1, reacts with (IPr)MCl (M = Cu, Ag, Au, IPr = 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) to afford the alkylidyne-bridged species [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)M(IPr)] 2-M. Interestingly, π-bonding of group 11 metals to the Ta—C moiety promotes a rare alkylidyne alkyl to bis-alkylidene tautomerism, in which compounds 2-M are in equilibrium with [Ta(CHtBu)(CH2tBu)2(μ-CHtBu)M(IPr)] 3-M. This equilibrium was studied in detail using NMR spectroscopy and computational studies. This reveals that the equilibrium position is strongly dependent on the nature of the coinage metal going down the group 11 triad, thus offering a new valuable avenue for controlling this phenomenon. Furthermore, we show that these uncommon bimetallic couples could open attractive opportunities for synergistic reactivity. We notably report an uncommon deoxygenative carbyne transfer to CO2 resulting in rare examples of coinage metal ketenyl species, (tBuCCO)M(IPr), 4-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au). In the case of the Ta/Li analogue 1, the bis(alkylidene) tautomer is not detected, and the reaction with CO2 does not cleanly yield ketenyl species, which highlights the pivotal role played by the coinage metal partner in controlling these unconventional reactions.

Introduction

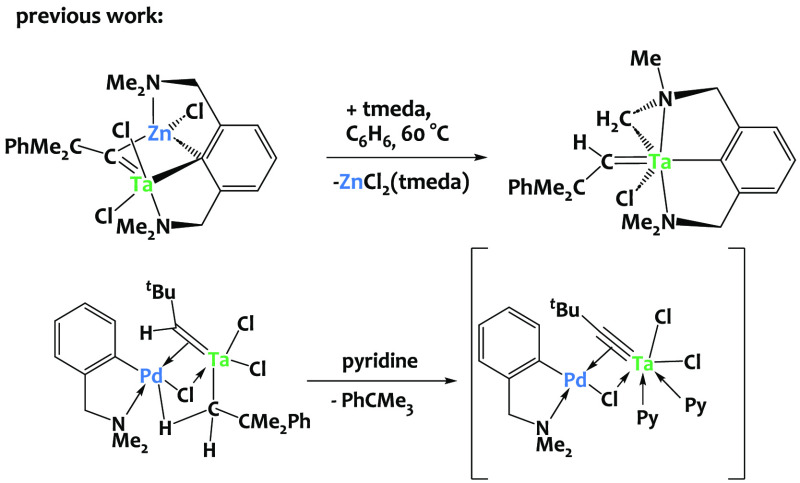

The π-activation of unsaturated hydrocarbons, such as alkenes, dienes, alkynes, or allenes, via coinage metals is well-established1−17 and led to numerous methodologies and applications, especially in organic chemistry and catalysis.18−33 Coinage metals are also known to efficiently coordinate to a number of heteroelement-based π-systems,34−47 yet practical applications of the latter still remain limited. Despite the interest of metal–carbon triple bonds in organometallic chemistry,48−51 the activation of M—C motifs via external d-block metal centers is still in its infancy. This is exemplified by the limited advancements observed in the context of tantalum alkylidynes, primarily restricted to their interaction with zinc cations to the best of our knowledge.52−55 Pfeffer and coworkers reported for instance an alkylidyne-bridged Ta/Zn species, which, in the presence of tmeda (tmeda = N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine), triggers intramolecular C–H bond activation (Scheme 1-top).53 The same group also described a Pd-bound Ta alkylidene alkyl complex which, upon treatment with pyridine, leads to an unstable compound tentatively assigned to a Pd-coordinated tantalum alkylidyne (Scheme 1-bottom), but the latter could not be isolated.56 These pioneering examples suggest that external metal reagents may serve as effective tools for controlling the reactivity of Ta alkylidyne moieties, offering the possibility of promoting atypical bimetallic C–H activations.57 Yet to date coordination of transition metals to Ta—C moieties has not been exploited to trigger unusual reactivity.

Scheme 1. Literature Precedents for Tantalum Alkylidyne Reactivity with d-Block Metals.

Given the unique advantage of coinage metals for π-bonding to substrates, our interest was thus sparked in examining their interaction with Ta alkylidynes. This exploration not only has the potential to fine-tune the reactivity of the latter but could also open up a promising avenue for initiating carbyne transfer reactions. This is particularly noteworthy since the stabilization of coinage metal carbynes is extremely challenging,58,59 despite their high interest and potential applications in organic chemistry and catalysis.

In this study, we illustrate that the tantalum alkylidyne moiety can efficiently bind coinage metal centers, leading to novel, well-defined, heterobimetallic compounds and triggering unusual reactivity. Specifically, we document an unusual deoxygenative carbyne transfer to CO2, resulting in rare examples of coinage metal ketenyl M-C(tBu)=C=O species (M = Cu, Ag, Au). The synthesis of ketenyls has received a notable surge in interest among organic and organometallic chemists in the past years,60−66 but these are typically prepared from CO rather than CO2. Cu(I) and Ag(I) ketenyl species were also proposed and debated as pivotal intermediates within catalytic cycles, for instance in the Kinugasa reaction, but had remained elusive and never isolated.33,67−70 The bimetallic reactivity reported here could therefore open up new perspectives in carbyne transfer chemistry or catalysis.

Results and Discussion

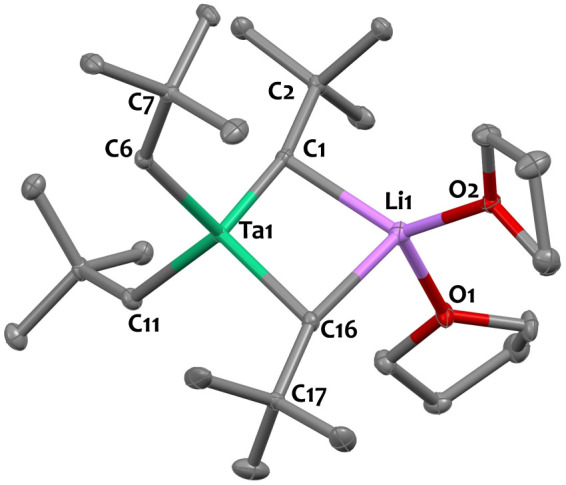

As part of our work in the preparation of tantalum-based early/late heterobimetallic complexes,71 −75 we contemplated the use of the ate-complex [Li(THF)2][Ta(CtBu)(CH2tBu)3], 1,52 as an entry point via salt metathesis.76−78 We determined the solid-state structure of 1 by single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 1), intending to establish a reference point for comparing metrical parameters with other compounds discussed in this study (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Solid state structure of 1. Ellipsoids are represented with 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected distances (Å) and angles (deg): Ta1–Li1 2.872(5), Ta1–C1 1.838(3), Ta1–C6 2.170(3), Ta1–C11 2.177(3), Ta1–C16 2.220(3), Li1–C1 2.223(6), Li1–C16 2.468 (6), Ta1–C1–C2 166.4(2), Ta1–C6–C7 131.2(2), Ta1–C16–C17 118.9(2).

Table 1. Key Structural Parameters (Distances in Å and Angles in °) for 1, 2-Cu, 2-Ag, 2-Au, and 3-Aua.

| 1 | 2-Cu | 2-Ag | 2-Au | 3-Au | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ta1–M | 2.872(5) | 2.7018(8) | 2.95(3) | 2.9462(3) | 2.9376(4) |

| Ta1–C1 | 1.838(3) | 1.844(2) | 1.878(4) | 1.882(6) | 2.05(1) |

| Ta1–C6 | 2.170(3) | 2.161(3) | 2.17(1) | 2.163(6) | 1.921(8) |

| Ta1–C11 | 2.177(3) | 2.167(2) | 2.176(4) | 2.172(6) | 2.165(9) |

| Ta1–C16 | 2.220(3) | 2.223(2) | 2.202(3) | 2.174(6) | 2.184(8) |

| M–C1 | / | 2.011(2) | 2.176(7) | 2.032(5) | 2.121(7) |

| M–C21 | / | 1.919(2) | 2.122(3) | 2.082(5) | 2.046(7) |

| Ta1–M–C21 | / | 166.4(1) | 161.3(4) | 164.8(2) | 144.6(2) |

| Ta1–C1–C2 | 166.4(2) | 157.3(2) | 157(2) | 149.8(4) | 135.8(6) |

| Ta1–C6–C7 | 131.2(2) | 132.7(2) | 136(2) | 132.9(2) | 166.1(7) |

For 2-Ag, average values between both molecules found in the asymmetric unit. M = Li, Cu, Ag, or Au.

The reaction between 1 and (IPr)CuCl affords the heterobimetallic complex [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)Cu(IPr)], 2-Cu (Scheme 2), which is isolated in excellent yield (93%). Compound 2-Cu is diamagnetic. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2-Cu indicates that the three CH2tBu groups are equivalent in solution, resulting in two signals at 0.68 and 1.28 ppm, for the CH2 and tBu moieties, respectively. The analysis of the 13C{1H}-NMR spectrum of 2-Cu reveals a distinct characteristic resonance at 286.52 ppm for the Ta—C alkylidyne moiety,54,79 akin to complex 1 (281.77 ppm). The CNHC carbene signal is observed at 185.57 ppm, which is consistent with literature data for (IPr)Cu(I) species.80

Scheme 2. Salt Metathesis Preparation of the Heterobimetallic Complexes [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)2M(IPr)], 2-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au, IPr = 1,3-Bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene).

Two extreme resonance forms are shown.

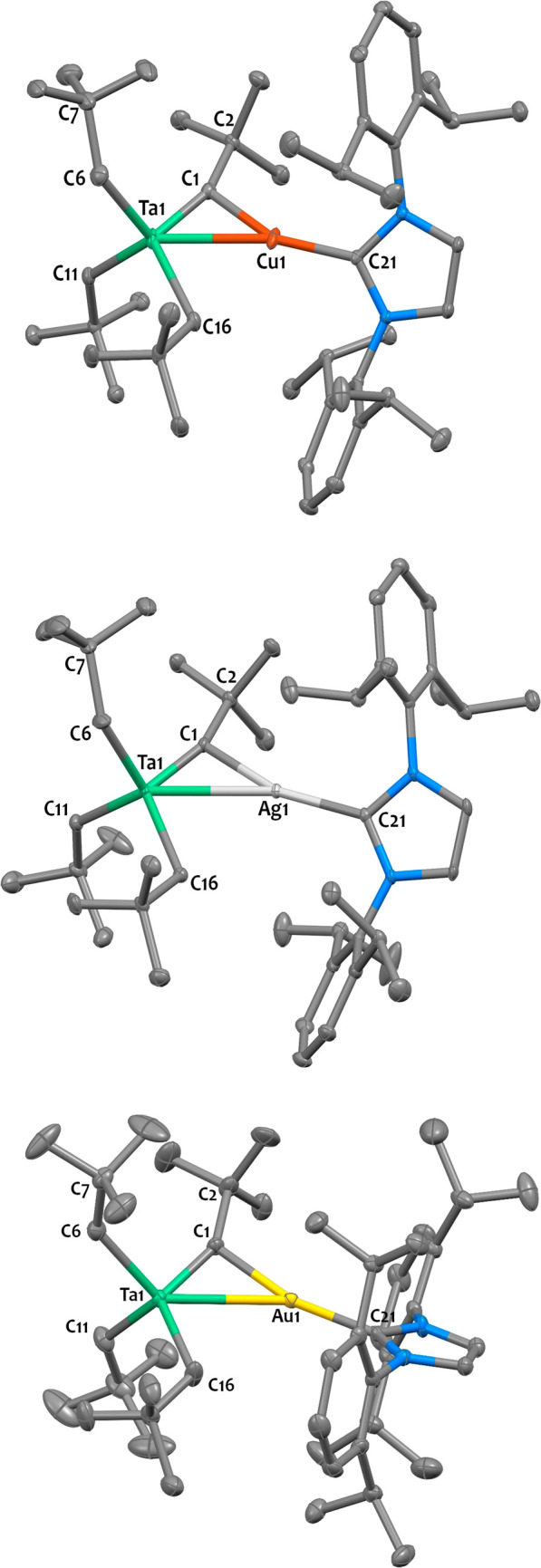

The solid-state structure of 2-Cu, determined by XRD, is shown in Figure 2 (top) and confirms the side-on coordination of the alkylidyne to the cationic Cu(NHC)+ fragment. The Ta–C1 bond length (1.844(2) Å) in 2-Cu is similar to that in 1 (1.838(3) Å) and that in the monometallic terminal alkylidyne complex Ta(CPh)(Cp*)2(PMe3) (1.849(8) Å).81 This distance is significantly shorter than that typically found in ditantalum μ-alkylidyne species [1.93–1.99 Å]82 or tantalum neopentylidene complexes [1.90–2.03 Å].56,71,72,74,83−85 This suggests that the Ta1–C1 bond has a significant triple bond character, as represented in the extreme resonance form in Scheme 2-right. Similar distances are found in related tantalum–zinc μ-alkylidyne species [1.79–1.86 Å].53−55 The negligible deviation of C2 from the Ta1–C1–Cu1 plane (0.03(2) Å) is consistent with a pseudosp hybridized C1 center. The angle between the Ta1–C1 centroid, Cu1 and C21 from the NHC ligand (174.0(2)°) is close to linearity, a typical coordination geometry around Cu(I) centers. The Cu1–C21 distance (1.919(2) Å) is in agreement with literature data for copper(I)-NHC heterobimetallic complexes,80,86 and the NHC carbon, C21, lies almost exactly in the Ta1–C1–Cu1 plane (mean deviation: 0.11(1) Å).

Figure 2.

X-ray determined solid state structures for 2-Cu (top), 2-Ag (middle), and 2-Au (bottom). Ellipsoids are represented with 30% probability. Disorder and hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Two independent molecules were found in the asymmetric unit of 2-Ag (Z′ = 2), but one of them has been omitted for clarity. Selected distances (Å) and angles (deg) for 2-Cu: Ta1–Cu1 2.7018(8), Ta1–C1 1.844(2), Ta1–C6 2.161(3), Ta1–C11 2.167(2), Ta1–C16 2.223(2), Cu1–C1 2.011(2), Cu1–C21 1.919(2), Ta1–Cu1–C21 166.4(1), Ta1–C1–C2 157.3(2), Ta1–C6–C7 132.7(2); for 2-Ag: Ta1–Ag1 2.95(3), Ta1–C1 1.878(4), Ta1–C6 2.17(1), Ta1–C11 2.176(4), Ta1–C16 2.202(3), Ag1–C1 2.176(7), Ag1–C21 2.122(3), Ta1–Ag1–C21 161.3(4), Ta1–C1–C2 157(2), Ta1–C6–C7 136(2); for 2-Au: Ta1–Au1 2.9462(3), Ta1–C1 1.882(6), Ta1–C6 2.163(6), Ta1–C11 2.172(6), Ta1–C16 2.174(6), Au1–C1 2.032(5), Au1–C21 2.082(5), Ta1–Au1–C21 162.8(2), Ta1–C1–C2 149.8(4), Ta1–C6–C7 132.9(2).

Molecular compounds associating Ta and Cu are extremely rare in the literature,87−90 and to our knowledge, there is no structurally characterized tantalum/copper molecular complex featuring an unsupported metal–metal interaction (i.e., without bridging ligands) reported to date. A search in the CCDC database for Ta–Cu species, where the two metal centers are separated by 2.7 Å or less revealed only one recent study from Buss and Maiola, who reported hydride-bridged species, in which the Ta–Cu distances span the range [2.61–2.90 Å].90 The Ta–Cu distance in 2-Cu (2.7018(8) Å) is falling in this range, which is in between the sum of the respective metallic radii (Ta: 1.343 Å; Cu: 1.173 Å; sum = 2.516 Å)91 and covalent radii (Ta: 1.70 Å; Cu: 1.32 Å; sum = 3.02 Å).92 This provides a potential avenue for metal–metal interactions.

The silver and gold analogues, 2-Ag and 2-Au, were synthesized in excellent yields (92% and 89%, respectively) from the analogous reaction between 1 and (IPr)MCl (M = Ag, Au). In all cases, the NMR spectra were consistent with a single neopentyl and IPr environment, implying free rotation at room temperature on the NMR time scale.

The solid-state structures for 2-Ag and 2-Au are reproduced in Figure 2. Both compounds feature similar geometry, with the C2 and C21 carbons lying in the same plane than the Ta1–C1–M1 (M = Ag or Au) core. The Ta1–C1 distance is elongated from 1.844(2) Å in 2-Cu to 1.878(4) Å in 2-Ag and to 1.882(6) Å in 2-Au. The M–C21 bond lengths (M = Ag, 2.122(3) Å; M = Au, 2.082(5) Å) are comparable to those in different coinage metal NHC complexes reported in the literature.93,94 Note that compounds associating tantalum with silver or gold are exceedingly rare in the literature.87 Only one complex, Ph3PAuTa(CNDipp)6 (Dipp = 2,6-diisopropylphenyl), which features an unsupported metal–metal bond of 2.7207(2) Å,95 is reported in the CCDC database.

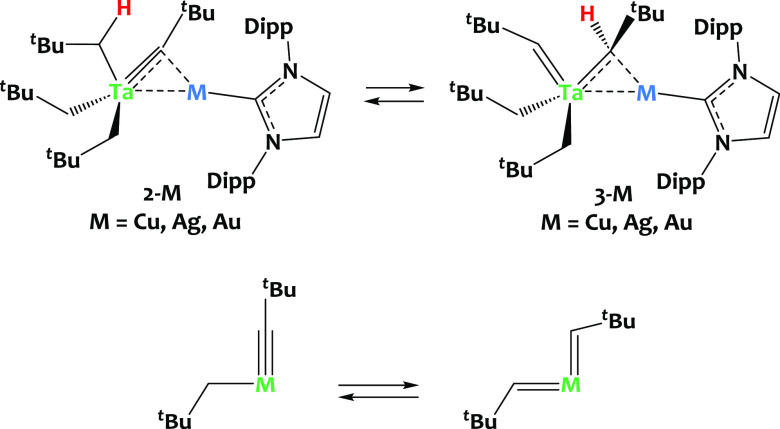

Interestingly, we observed that, in C6D6 solution (or toluene-d8), complexes 2-M slowly tautomerize into 3-M [Ta(CHtBu)(CH2tBu)2(μ-CHtBu)M(IPr)] (M = Cu, Ag, Au, Scheme 3-top). Such alkylidyne alkyl to bis(alkylidene) tautomerism equilibrium (Scheme 3-bottom) is a rare phenomenon. Such a rearrangement was first postulated by Schrock and coworkers to account for the quantitative formation of TaCp(CHtBu)2(PMe3) from treating TaCp(CtBu)Cl(PMe3)2 with Mg(CH2tBu)2(dioxane)102 and has then been documented in a few cases with W and Os derivatives.96−101 In these examples from literature, the relative stability of each tautomer depends on the nature of ancillary ligands, yet structural preference is difficult to predict and control. Still, in the case of (Me3SiCH2)3W—CSiMe, Xue and coworkers have demonstrated that the coordination of external phosphine ligands such as PMe3 could trigger this tautomeric equilibrium, helping to stabilize of the bis(alkylidene) tautomer (Me3SiCH2)2W(=CHSiMe3)2(PMe3).98,99 It is important to mention here that C6D6 solutions of compound 1 are stable over time at room temperature, and that the bis(alkylidene) tautomer is not observed in the absence of coinage metals.

Scheme 3. (Top) Equilibrium between the Alkylidyne-Bridged Species 2-M and Alkylidene-Bridged Species, 3-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au); (Bottom) Alkyl Alkylidyne/Bis-alkylidene Tautomerism Equilibrium96−101.

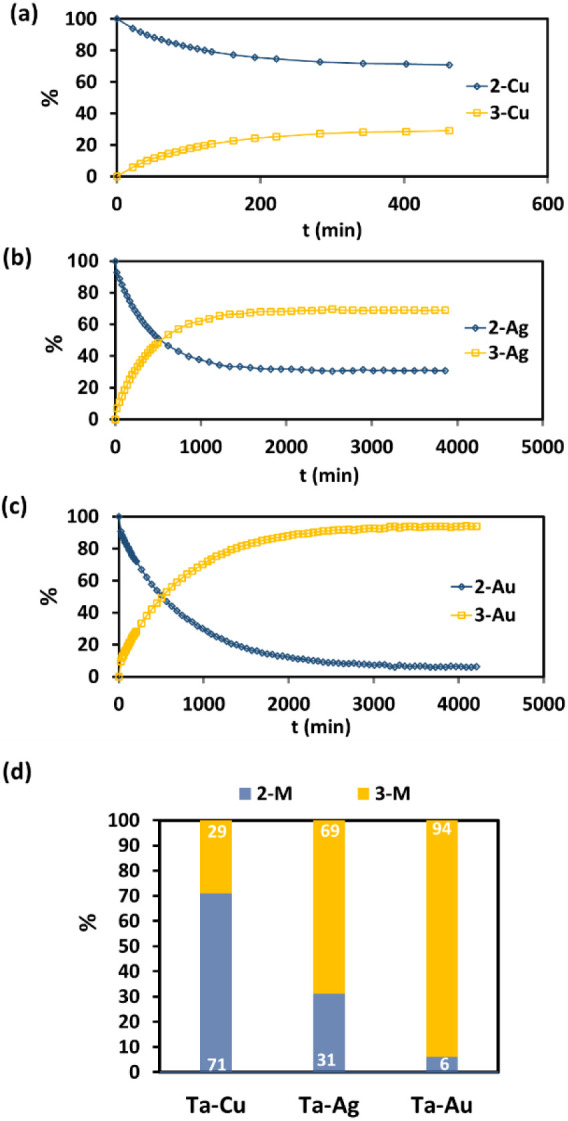

Significantly, our findings reveal that the tautomeric equilibrium is not only initiated but also remarkably influenced by the choice of the coinage metal, as illustrated in Figure 3. In the heterobimetallic Ta/Cu system, the equilibrium in C6D6 solution at 30 °C predominantly favors the formation of complex 2-Cu (2-Cu:3-Cu ratio at equilibrium 71%:29%). In contrast, within the Ta/Ag system, the equilibrium shifts toward 3-Ag, with an equilibrium ratio of 31 to 69% in favor of 3-Ag over 2-Ag at 30 °C. This shift is even more pronounced in the Ta/Au system, where the equilibrium ratio between 2-Au and 3-Au is 6% to 94%, demonstrating a significant preference for the formation of 3-Au over 2-Au. These findings underscore the sensitivity of the tautomeric equilibrium to the specific late metal component in the complex, offering a valuable avenue for controlling this phenomenon.

Figure 3.

(a–c) Evolution in the percentages of complexes 2-M and 3-M as a function of time in C6D6 solution at 303 K. (d) 2M:3M ratio at equilibrium. The equilibrium position is shifted as we move down the group 11 metal column, favoring the tantalum bis-neopentylidene over tantalum neopentyl neopentylidyne tautomer.

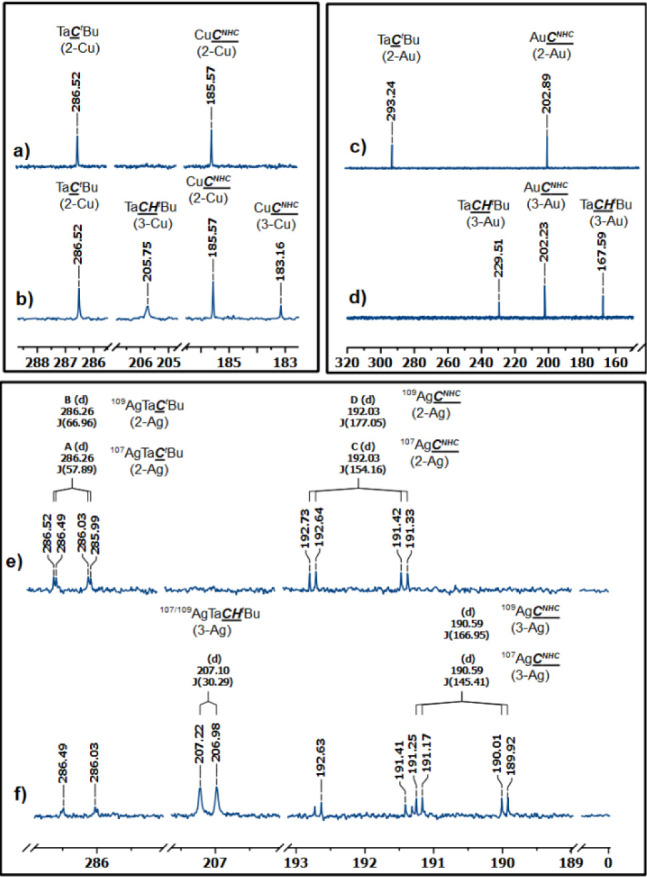

Complexes 3-Cu and 3-Ag were characterized in the reaction mixture by conducting a comparative analysis of 13C NMR spectra at both the initial time (t = 0) and at equilibrium (at 298 K). The formation of the new copper carbene species, 3-Cu, was evidenced by the appearance of an additional Cu–CNHC signal at 183.16 ppm, in addition to that found for 2-Cu at 185.57 ppm (Figure 4b). 13C NMR studies suggest that the two alkylidene ligands in 3-Cu are fluxional in solution, which is manifested by the appearance of a broad signal centered at 205.75 ppm (Figure 4c). This value falls in the lower end of the range typical for Ta(V) neopentylylidenes.71,72,74 Similar observations were made for the 2-Ag/3-Ag equilibrium mixture; yet, in this case, the 13C NMR signals display fine structure due to coupling with naturally abounding spin 1/2 107Ag and 109Ag isotopes. Consequently, the CNHC signal in 3-Ag appears as a doublet of doublets at 190.59 ppm (1JAg–C = 145.4 and 167.0 Hz for 107Ag and 109Ag, respectively, see Figure 4f), in agreement with the literature.93,103 The neopentylidene signal in 3-Ag is observed as a broad doublet, displaying a coupling constant of 30.3 Hz with silver (Figure 4f). These observations confirm the interaction of silver with the NHC and both neopentylidene moieties in 3-Ag on the NMR time scale.

Figure 4.

13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz) spectra of (a) compound 2-Cu in C6D6 at 298 K, (b) equilibrium mixture of 2-Cu and 3-Cu in C6D6 at 298 K, (c) compound 2-Au in C6D6 at 298 K, (d) compound 3-Au in toluene-d8 at 253 K, (e) compound 2-Ag in C6D6 at 298 K, (f) equilibrium mixture of 2-Ag and 3-Ag in C6D6 at 298 K.

Due to the pronounced equilibrium preference for 3-Au, we successfully isolated and characterized it independently. At room temperature, the NMR signals of complex 3-Au displayed significant broadening, presenting challenges in their assignment. This phenomenon is attributed to the rapid exchange between the two Ta=CHtBu motifs at the NMR time scale (see the VT 1H NMR data in Figure S37). Cooling the sample to 253 K resulted in the emergence of three distinct sharp signals in the carbene region at 229.51, 202.23, and 167.59 ppm, corresponding to the TaCHtBu, AuCNHC, and Ta(μ-CHtBu)Au motifs, respectively (see Figure 4d), consistent with the proposed molecular structure. The bridging neopentylidene 13C NMR resonance is strongly high-field shifted compared to the nonbridging neopentylidene moiety, as was reported previously in a TaRh(μ-CHtBu) species (δ= +170.1 ppm).71 Note that the neopentylidene α-H resonances observed in the 1H NMR spectra of complexes 3-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au) appear in very upfield regions (1.5–2.2 ppm). Although typical values are comprised between +3 and +7 ppm,71,74,104,105 there are a number of examples that deviate from this range, demonstrating upfield resonances. For instance, in compound Ta(=CHtBu)(CH2tBu)3, the α-H signal of the neopentylidene ligand in C6D6 solution at room temperature appears at +1.9 ppm.107,106 Similarly, in other compounds such as [Li][{Ta(CHtBu)(CH2tBu)2}{IrH2Cp*},72 Tp′Ta(NMe2)(CHtBu)Cl, and Tp′Ta(CHtBu)Br2,108 the neopentylidene resonance is found at +0.98; +1.68, and +1.88 ppm, respectively.

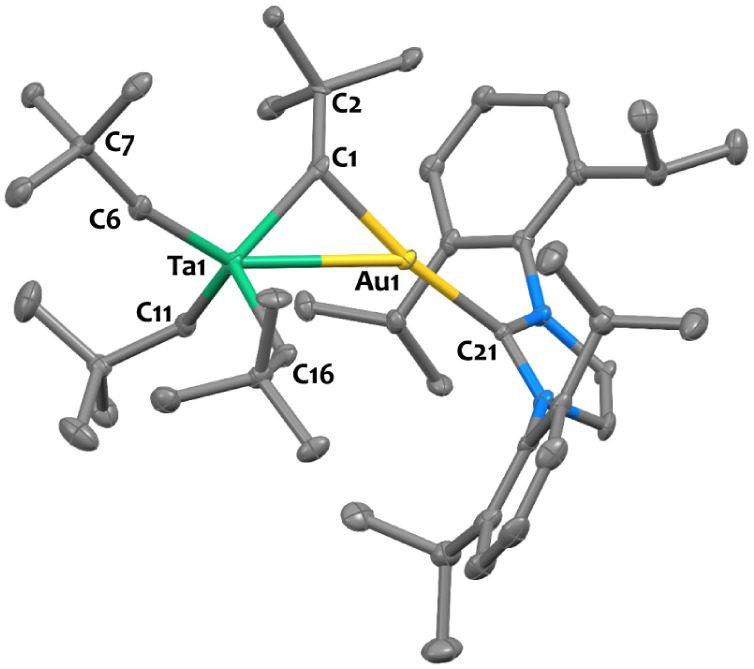

Additionally, 3-Au was crystallized from pentane through slow evaporation, and the solid-state structure was elucidated using single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 5). The Ta1–C1 distance in 3-Au (2.05(1) Å) is significantly elongated compared to that in 2-Au (1.882(6) Å), and the Ta1–C6 bond length is shortened (1.921(8) Å in 3-Au vs 2.163(6) Å in 2-Au), as expected. As a result of H transfer, the geometry around the C1 center shifts from pseudo trigonal planar in 2-Au, to pseudo tetrahedral in 3-Au, as shown by the mean deviation of C1 atom from the Ta1–Au1–C2 plane (0.01(1) Å in 2-Au vs 0.49(1) Å in 3-Au). The Ta1–C6–C7 angle is increased, from 132.9(2)° in 2-Au to 166.1(7)° in 3-Au. Such obtuse angle is frequently observed in primary alkylidenes,71,74,84,109 as a result of C–H agostic interaction, further confirming the bis-alkylidene nature of complex 3-Au. Note that the presence of this agostic interaction is confirmed by DFT calculations, showing short Au–H distance and elongated C–H distance in the computed structure for 3-Au (see Figure DFT-7 in Supporting Information). In NBO analysis, we also see a stronger donation of the C–H bond to the Ta center for 3-Au. The distance between the Au atom and the Ta–C1 multiple bond centroid is almost identical in 2-Au (2.37(1) Å) and 3-Au (2.35 Å). This tends to suggest that the π-bonding of the gold center to the tantalum carbon multiple bonds is similar in both tautomers.

Figure 5.

X-ray determined solid-state structure for complex 3-Au. Ellipsoids are represented with 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected distances (Å) and angles (deg): Ta1–Au1 2.9376(4), Ta1–C1 2.05(1), Ta1–C6 1.921(8), Ta1–C11 2.165(9), Ta1–C16 2.184(8), Au1–C1 2.121(7), Au1–C21 2.046(7), Ta1–Au1–C21 144.6(2), Ta1–C1–C2 135.8(6), Ta1–C6–C7 166.1(7).

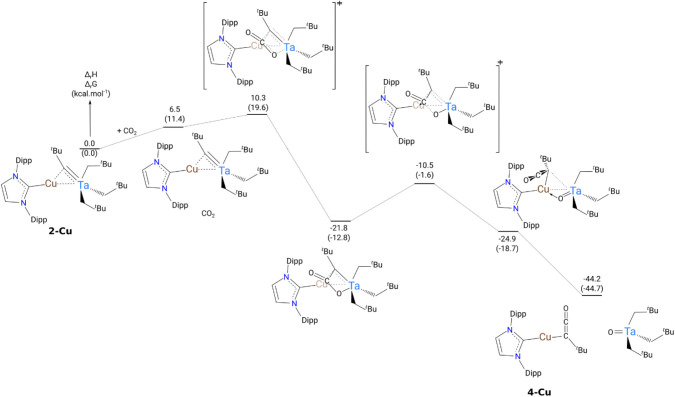

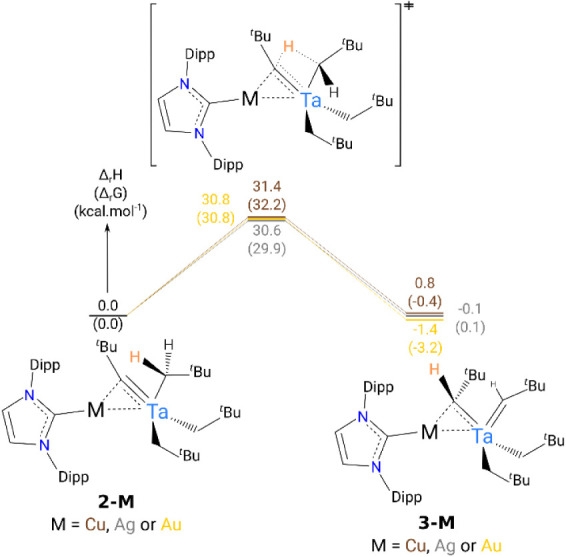

To better understand this phenomenon, DFT calculations were carried out (B3PW91 functional) including or not dispersion corrections. The optimized geometries of 2-Cu, 2-Ag, 2-Au, and 3-Au compare well with the experimental ones (see Supporting Information). The reaction profile for the tautomerism reaction (Figure 6) implies a Ta-assisted hydrogen transfer from the neopentyl to the alkylidyne. The computed barrier is in the 30–31 kcal·mol–1 range depending on the metal, in line with the lack of inclusion of the coinage metal at the transition state. It is interesting to note that the formation of 3-Cu from 2-Cu is slightly endothermic by 0.8 kcal.·mol–1, which fits with the experimental observation of 2-Cu being more stable than 3-Cu (experimental ratio 2-Cu:3-Cu 71%:29%). In the Ag and Au cases, the formation of 3-Ag and 3-Au is exothermic by 0.1 and 1.4 kcal·mol–1, respectively, in line with the experimental observation (2-M:3-M ratio for M = Ag 31%:69% and for M = Au 6%:94%). It is interesting to notice that the inclusion of the dispersion correction does not improve the result and even does not fit with the experimental thermodynamic parameters (the reaction is becoming very endothermic for Cu). Analyses of the computed metrical parameters and charges suggest that the Au–Ccarbyne interaction is weaker than the Ag–Ccarbyne and Cu–Ccarbyne interactions. This trend is corroborated by natural charge calculations (see Figure DFT-5 in Supporting Information), where, overall, the charge on gold (+0.31) is smaller than those on Ag (+0.44) and Cu (+0.46) in compounds 2-M, which could promote such tautomerism.

Figure 6.

Computed energy profile at room temperature for the tautomerism reaction 2-M ⇌ 3-M. The energies are given in kcal·mol–1.

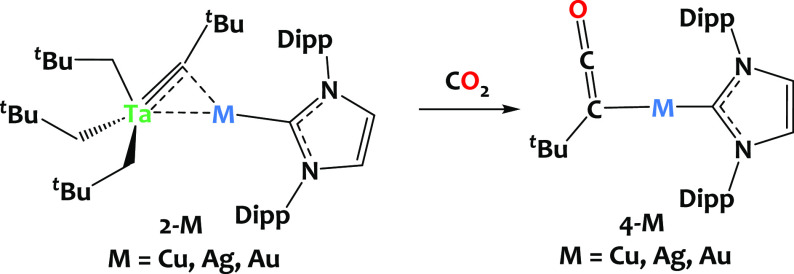

To illustrate the potential of these new bimetallic architectures to promote cooperative reactivity, we studied the reaction of complexes 2-M with a CO2 atmosphere (ca. 0.7 mbar, 2 equiv). The reaction was carried out in pentane at −80 °C for 10 min and then at room temperature for 1h. This led to the precipitation of the ketenyl complexes, (tBuCCO)M(IPr), 4-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au, see Scheme 4), which were isolated as white solids in 48% to 77% yields. The moderate yield is attributed, at least in part, to the partial solubility of compounds 4-M in pentane, which is employed for washing the materials.

Scheme 4. Reaction of Compounds 2-M with CO2 Producing the Ketenyl Complexes (tBuCCO)M(IPr), 4-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au).

Complexes 4-M were fully characterized by NMR and IR spectroscopy. The 1H NMR spectra show a singlet at δ = 1.15 ppm attributed to the tBu group in 4-Cu (corresponding signal found at δ = 1.21 and 1.16 ppm for 4-Ag and 4-Au, respectively). In the 13C NMR spectra, the ketenyl moiety gives rise to characteristic signals at δ = 169.89, 169.38, and 181.19 ppm for the central C atom and δ = 24.39, 23.70, and 32.00 ppm for Cα in 4-Cu, 4-Ag, and 4-Au, respectively.61,110−112 The CNHC13C NMR signals are found at 183.83 ppm for 4-Cu, 189.20 ppm for 4-Ag, and 193.39 ppm for 4-Au, as expected.80 In the DRIFT spectra, the strong absorption bands at 2012 cm–1 for 4-Cu, 2016 cm–1 for 4-Ag, and 2027 cm–1 for 4-Au confirm the presence of the ketenyl fragment (see Figure S66). This infrared ν(CCO) absorption is red-shifted in comparison to the typical range for ketenes (2120–2070 cm–1).62,113−115 For comparison, in the related compounds [M](CCO)tBu (where [M] = Et3Ge, Bu3Sn), the corresponding stretches appear at 2070 and 2060 cm–1, respectively,110 and two recent articles describing ketenyl derivatives reported ν(CCO) absorptions at 2047 and 2030 cm–1.61,64

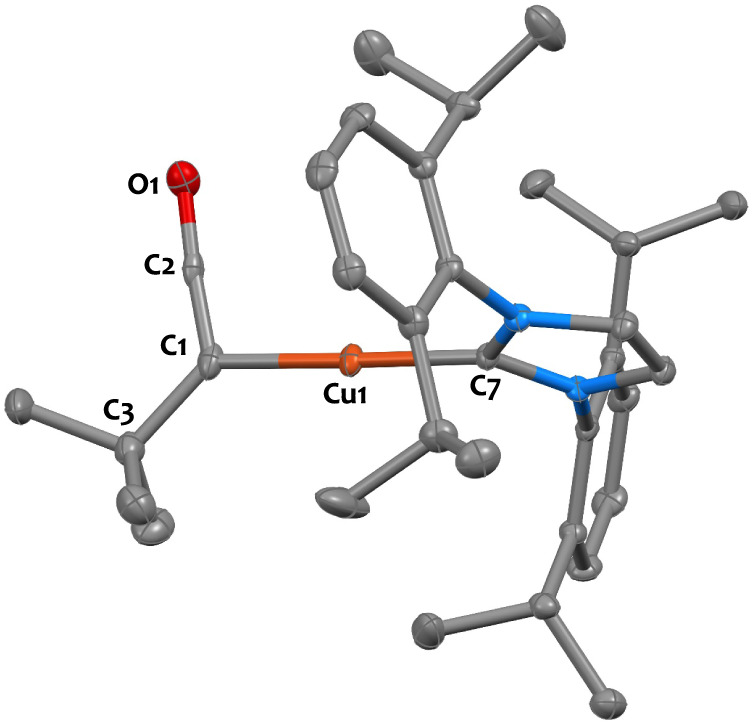

Conclusive evidence of the ketenyl moiety arises from the X-ray diffraction structure of compound 4-Cu, which is shown in Figure 7. The short C1–C2 and C2–O1 bond lengths as well as wide C1–C2–O1 angle (1.273(7) Å, 1.201(6) Å, and 174.8(4)°, respectively) support assignment as a η1C(tBu)=C=O ketenyl motif.61,62,66,113,116 The Cu(I) center adopts a linear geometry (C1–Cu1–C7 angle = 176.5(2)°), and the Cu1–C1 and Cu1–C7 bond lengths (1.908(4) Å and 1.891(4) Å, respectively) are akin that found in NHC copper(I) aryl complexes.117

Figure 7.

X-ray determined solid state structure for compound 4-Cu. Ellipsoids are represented with 30% probability. Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Selected distances (Å) and angles (deg): Cu1–C1 1.908(4), Cu1–C7 1.891(4), C1–C2 1.273(7), C2–O1 1.201(6), C1–C3 1.542(7), C1–Cu1–C7 176.5(2), C1–C2–O1 174.8(4), C3–C1–C2 126.0(4).

Ketenyl compounds have been relatively scarce in the scientific literature, even though there has been a notable surge in interest in the past years.60−66 Copper and silver ketenyl species have been proposed and debated as pivotal intermediates within catalytic cycles, for instance in the Kinugasa reaction.33,67−70 Despite their theoretical significance, these species remained elusive and were never isolated to the best of our knowledge, underscoring the scientific interest and relevance of compounds 4-M.

The originality of this family of ketenyl compounds is not confined to its structural features; it also extends to the uniqueness of its synthetic route. Traditionally, the prevalent approach to synthesizing ketenyl species relies on their preparation from carbon monoxide (CO). To the best of our knowledge, only one example of carbon dioxide cleavage leading to the formation of a ketenyl fragment was described in the literature.118 The proposed mechanism involves initial CO2 cycloaddition on a tungsten alkylidyne complex, [CF3–ONO]W—CCtBu(THF)2, to generate a heterometallacyclobutene, which then rearranges to yield a tungsten-oxo and the ketenyl moiety in [CF3–ONO]W—O[C(tBu)CO]. A comparable mechanism may be proposed here, involving the putative formation of a [(CH2tBu)3Ta=O]n species and then subsequent transfer of the ketenyl moiety to the M(IPr) fragment (M = Cu, Ag, Au). Regrettably, our attempts to definitely identify or isolate this tantalum-oxo coproduct were unsuccessful despite major efforts, primarily due to the very high solubility of the compound and the likelihood of it adopting various oligomeric structures in solution. In light of the burgeoning of emerging and novel heterobimetallic CO2 cleavage pathways documented in the literature,119−127 it is also conceivable that a concerted carbon dioxide activation may occur across the tantalum-coinage metal centers.

We further investigated the reaction of the Ta/Li carbyne complex 1 with CO2 (2 equiv) in pentane under the same experimental conditions. This reaction yielded a precipitate, indicative of a chemical transformation taking place. However, the complexity of this reaction was evidenced by the analysis of this solid using 1H NMR spectroscopy, which revealed the formation of a mixture comprising numerous species (see Figure S64). Despite our efforts, the identification of these products remained elusive. This observation underscores the complexity of the reaction mechanism and highlights the pivotal role played by the coinage metal partner in stabilizing the ketenyl fragment in this reaction.

To shed light on the possible mechanisms explaining the unusual formation of complex 4, DFT calculations (B3PW91) have been performed (Figure 8). The reaction begins by the formation of a van der Waals adduct of CO2 to 2-Cu, which is endothermic by 6.5 kcal·mol–1. To form this adduct, CO2 has to open some space in between the Dipp and tBu ligands explaining the positive enthalpy of formation. From this adduct, CO2 undergoes a [2 + 2] cycloaddition on the Ta—C–tBu bond with an associated low barrier (10.3 kcal·mol–1). Following the intrinsic reaction coordinate, it yields to a stable metallacyclobutane-type intermediate (−21.8 kcal·mol–1). In this intermediate, the carbon of the former alkylidene interacts with both Ta and Cu, while the carbon of CO2 is not interacting with any metal. The coordination of the carbon of CO2 to Cu allows the activation of the C–O bond of this stable intermediate. The associated barrier is 11.3 kcal·mol–1 in line with a kinetically facile reaction. This ultimately yields complex 4-Cu and the formation of a Ta=O complex, which are found to be highly stable (−44.2 kcal·mol–1).

Figure 8.

Computed reaction pathway of the formation of 4-Cu at room temperature. The energies are given in kcal·mol–1.

Conclusion

A salt metathesis synthetic strategy has been used with success to access rare tantalum/coinage metals heterobimetallic complexes [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)M(IPr)] 2-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au, IPr = 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) in high yields. Despite the large body of fundamental work dedicated to the study of transition metal alkylidene and alkylidyne complexes, the alkylidyne/alkyne tautomerism equilibrium is a rarely observed phenomenon. Here, we show for the first time that the addition of an external coinage metal center, with affinity for π-bonding to the tantalum–carbon multiple bond, can be used as a strategy to trigger and tune this unusual tautomerism equilibrium (Cu < Ag < Au). Given the importance of metal alkyllidynes/alkylidenes in catalysis, this work could open new avenues for reactivity.

Furthermore, we show that these uncommon heterobimetallic complexes could open attractive opportunities for synergistic reactivity. We notably report an unusual deoxygenative carbyne transfer to CO2 resulting in rare examples of coinage metal ketenyl species, (tBuCCO)M(IPr), 4-M (M = Cu, Ag, Au). Interestingly, in the case of the Ta/Li analogue 1, the bis(alkylidene) tautomer is not detected, and the reaction with CO2 does not cleanly yield ketenyl species, which highlights the pivotal role played by the coinage metal partner in controlling these unconventional reactions. This innovative reactivity could open up new avenues for exploring various synthetic possibilities in the fast-growing field of ketenyl species.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were performed either using standard Schlenk line techniques or in an MBRAUN glovebox under an atmosphere of purified argon (<1 ppm of O2/H2O). Glassware and cannulas were stored in an oven at ∼100 °C for at least 16 h prior to use. THF and n-pentane were purified by passage through a column of activated alumina, dried over Na/benzophenone, vacuum-transferred to a storage flask, and freeze–pump–thaw degassed prior to use. Deuterated solvents (toluene-d8, THF-d8, and C6D6) were dried over Na/benzophenone, vacuum-transferred to a storage flask, and freeze–pump–thaw degassed prior to use. Compound [Ta(CH2tBu)3(CHtBu)] was prepared according to the literature procedure.52 All other reagents were acquired from commercial sources and used as received.

IR Spectroscopy

The samples were prepared in a glovebox (diluted in dry KBr), sealed under argon in a DRIFT cell fitted with KBr windows, and then analyzed using a Nicolet 670 FT-IR spectrometer.

Elemental Analyses

Elemental analyses were performed under an inert atmosphere at Mikroanalytisches Labor Pascher, Germany.

X-Ray Structural Determinations

Experimental details regarding single-crystal XRD measurements are provided in the Supporting Information. CCDC 2310994–2310999 contain supplementary crystallographic data for this article. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre viawww.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

NMR Spectroscopy

Solution NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AV-300 and AV-500 spectrometers. 1H and 13C chemical shifts were measured relative to residual solvent peaks, which were assigned relative to an external TMS standard set at 0.00 ppm. 1H and 13C NMR assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H COSY, 1H–13C HSQC, and HMBC experiments. NMR data recorded as follows: chemical shift (δ) [multiplicity, coupling constant(s) J (Hz), relative integral], where multiplicity is defined: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet or combinations thereof, and prefixed br = broad.

Synthesis of [Li(THF)2][Ta(CH2tBu)3(CtBu)] (1)

This synthesis was adapted from a published procedure.52 A 0.77 mL hexane solution of n-BuLi (1.6 M, 1.23 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added dropwise, at −40 °C, to a 10 mL orange pentane solution of [Ta(CH2tBu)3(CHtBu)] (500 mg, 1.08 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and THF (0.35 mL, 4.32 mmol, 4.0 equiv). The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the volatiles were removed under vacuum, yielding a yellow solid. This powder was dissolved in the minimum amount of pentane (ca. 6 mL) and stored at −40 °C for 16 h, yielding after filtration and drying under vacuum compound 1 as orange crystals (412 mg, 62% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 3.56 (m, 8H, THF), 1.61 (s, 9H, CC(CH3)3), 1.44 (s, 27H, 3 CH2C(CH3)3), 1.35 (m, 8H, THF), 0.65 (s, 6H, 3 CH2Ta). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 281.77 (br s, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 101.46 (s, 3C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 68.88 (s, 4C, THF), 50.74 (s, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 36.99 (s, 3C, TaCC(CH3)3), 36.22 (s, 9C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 35.00 (s, 3C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 25.37 (s, 4C, THF). Anal. calcd for C28H58LiO2Ta: C, 54.71; H, 9.51. Found: C, 54.84; H, 9.52.

Synthesis of [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)Cu(IPr)] (2-Cu)

A 10 mL pentane solution of [Li(THF)2][Ta(CH2tBu)3(CtBu)] (300 mg, 0.49 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added dropwise at room temperature to a suspension of (IPr)CuCl (237 mg, 0.49 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 4 mL of pentane. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was filtered to remove the white LiCl precipitate. Then, the volatiles were removed under vacuum, yielding 2-Cu as an orange solid (415 mg, 93% yield). Orange block single crystals of 2-Cu suitable for XRD studies were grown by slow recrystallization of a pentane saturated solution at −40 °C over a period of 16 h. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.21–7.14 (m, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.09 (d, 3J1H-1H = 7.7 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.46 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH-N), 3.04 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.40 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.38 (s, 9H, TaCC(CH3)3), 1.28 (s, 27H, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 1.00 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 0.68 (s, 6H, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 286.52 (s, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 185.57 (s, 1C, CuCNHC), 145.17 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 136.38 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.32 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.89 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 123.13 (s, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 104.79 (s, 3C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 51.03 (s, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 37.76 (s, 3C, TaCC(CH3)3), 36.08 (s, 9C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 35.33 (s, 3C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 28.92 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 25.27 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 23.98 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr). Anal. calcd for C47H78CuN2Ta: C, 61.65; H, 8.59; N, 3.06. Found: C, 61.54; H, 8.47; N, 3.03.

Synthesis of [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)Ag(IPr)] (2-Ag)

A 6 mL pentane solution of [Li(THF)2][Ta(CH2tBu)3(CtBu)] (200 mg, 0.32 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added dropwise to a suspension of (IPr)AgCl (168.6 mg, 0.32 mmol, 1.0 equiv) in 4 mL of pentane. The resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was filtered to remove the white precipitate (LiCl). Then, the volatiles were removed under vacuum, yielding 2-Ag as an orange solid (280 mg, 92% yield). Orange block single crystals of 2-Ag suitable for XRD studies were grown by slow recrystallization of a pentane saturated solution at −40 °C over a period of 16 h. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.25–7.18 (m, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.09 (d, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.39 (d, 4J13C–109Ag = 4J13C–107Ag = 1.0 Hz, 2H, N–CH=CH–N), 2.78 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 4H, CH(CH3)2), 1.43–1.31 (m, 21H, 2 CH(CH3)2 and TaCC(CH3)3), 1.29 (s, 27H, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 1.02 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 0.74 (s, 6H, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 286.26 (d, 1J13C–109Ag = 66.96 Hz and d, 1J13C–107Ag = 57.89 Hz, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 192.03 (d, 1J13C–109Ag = 177.05 Hz and d, 1J13C–107Ag = 154.16 Hz, 1C, AgCNHC), 145.45 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 136.29 (br s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.67 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.80 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 123.43 (d, 3J13C–109Ag = 3J13C–107Ag = 4.85 Hz, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 103.73 (d, 2J13C–109Ag = 2J13C–107Ag = 2.45 Hz, 3C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 50.43 (d, 2J13C–109Ag = 2J13C–107Ag = 3.70 Hz, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 38.44 (d, 2J13C–109Ag = 2J13C–107Ag = 3.40 Hz, 3C, TaCC(CH3)3), 36.15 (s, 9C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 35.30 (s, 3C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 28.89 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.57 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.39 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr). Anal. calcd for C47H78AgN2Ta: C, 58.81; H, 8.19; N, 2.92. Found: C, 58,97; H, 8,20; N, 2,95.

Synthesis of [Ta(CH2tBu)3(μ-CtBu)Au(IPr)] (2-Au)

A 6 mL pentane solution [Li(THF)2][Ta(CH2tBu)3(CtBu)] (200 mg, 0.32 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added dropwise to a suspension of (IPr)AuCl (217 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1.1 equiv) in 4 mL of pentane. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The solution was then filtered to remove the white precipitate (LiCl). Subsequently, the volatiles were removed under vacuum, yielding 2-Au as an orange/brown solid (390 mg, 89% yield). Single crystals of 2-Au, suitable for X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies, were grown by slow recrystallization of a pentane saturated solution at −40 °C over a period of 16 h. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.24 (t, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.10 (d, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.33 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH-N), 2.85 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 4H, CH(CH3)2), 1.42 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.37 (s, 9H, TaCC(CH3)3), 1.28 (s, 27H, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 1.04 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 0.75 (s, 6H, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 293.24 (s, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 202.89 (s, 1C, AuCNHC), 145.50 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 136.27 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.66 (s, 2C, 2 para-CHAr), 124.84 (s, 4C, 4 meta-CHAr), 123.13 (s, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 108.48 (s, 3C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 50.21 (s, 1C, TaCC(CH3)3), 38.45 (s, 3C, TaCC(CH3)3), 36.09 (s, 9C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 35.89 (s, 3C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 28.93 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.49 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.15 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr). Anal. calcd for C47H78AuN2Ta: C, 53.81; H, 7.49; N, 2.67. Found: C, 54.02; H, 7.48; N, 2.63.

Characterization of [Ta(CH2tBu)2(μ-CHtBu)2Cu(IPr)] (3-Cu)

This product could not be isolated, but was characterized from the equilibrium mixture of 2-Cu and 3-Cu. This mixture was obtained by dissolving 50 mg of complex 2-Cu in 1 mL of C6D6 in a Young-type NMR tube and allowing it to sit at room temperature for 24 h. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.22–7.14 (m, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.09 (d, 3J1H–1H = 8.1 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.33 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH–N), 2.81 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.48 (s, 2H, 2 TaCHC(CH3)3), 1.42–1.35 (m, 30H, 2 CH(CH3)2 and 2 TaCHC(CH3)3), 1.34 (s, 18H, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 1.00 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 0.38 (s, 4H, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 205.75 (s, 2C, 2 TaCHC(CH3)3), 183.16 (s, 1C, CuCNHC), 145.40 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 135.62 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 131.03 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.66 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 123.33 (s, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 93.43 (s, 2C, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 45.58 (s, 2C, 2 TaCHC(CH3)3), 37.15 (s, 6C, 2TaCHC(CH3)3), 36.35 (s, 6C, 3 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 34.17 (s, 2C, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 28.92 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.98 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.10 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr).

Characterization of [Ta(CH2tBu)2(μ-CHtBu)2Ag(IPr)] (3-Ag)

This product could not be isolated but was characterized from the equilibrium mixture of 2-Ag and 3-Ag. This mixture was obtained by dissolving 50 mg of complex 2-Ag in 1 mL of C6D6 in a Young-type NMR tube and allowing it to sit at room temperature for 24 h. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.26–7.20 (m, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.07 (d, 3J1H-1H = 7.8 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.34 (d, 4J13C–109Ag = 4J13C–107Ag = 1.0 Hz 2H, N–CH=CH–N), 2.65 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 2.10 (s, 2H, 2 TaCHC(CH3)3), 1.42–1.35 (m, 30H, 2 CH(CH3)2 and 2 TaCHC(CH3)3), 1.33 (s, 18H, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 1.02 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 0.47 (s, 4H, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 207.10 (d, 1J13C–109Ag = 1J13C–107Ag = 30.29 Hz, 2C, TaCHC(CH3)3), 190.59 (d, 1J13C–109Ag = 166.95 Hz and d, 1J13C–107Ag = 145.41 Hz, 1C, AgCNHC), 145.49 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 135.61 (br s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.99 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.63 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 123.37 (d, 3J13C–109Ag = 3J13C–107Ag = 4.74 Hz, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 94.63 (s, 2C, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 45.00 (d, 2J13C-109Ag = 2J13C-107Ag = 1.10 Hz, 2C, TaCHC(CH3)3), 37.20 (d, 2J13C–109Ag = 2J13C–107Ag = 1.20 Hz, 6C, TaCHC(CH3)3), 35.62 (s, 6C, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 34.07 (s, 2C, 2 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 28.97 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.70 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.40 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr).

Synthesis of [Ta(CH2tBu)2(CHtBu)(μ-CHtBu)Au(IPr)] (3-Au)

In the glovebox, complex 2-Au (100 mg, 0.85 mmol) was dissolved in 3 mL of pentane within a 20 mL vial, and the mixture was left stirring overnight. Subsequently, the vial was gently opened to facilitate the gradual evaporation of pentane over an additional night, resulting in the formation of a yellow-orange crystalline solid. This solid was then promptly rinsed with approximately 1 mL of cold pentane (−40 °C), yielding 3-Au in the form of small yellow crystals (40 mg, 40% yield). Do to fluxional dynamics occurring on the NMR time scale at room temperature, resulting in signal broadening that complicates their assignment, the solution NMR characterization of 3-Au was conducted at 253 K. This lower temperature facilitated a more comprehensive and accurate signal assignment. 1H NMR (500 MHz, toluene-d8, 253 K) δ ppm 7.25 (t, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.11–6.98 (m, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.28 (s, 1H, N–CH=CH–N), 2.83 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 7.2 Hz, 2H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 2.67 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 7.2 Hz, 2H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 2.19 (s, 1H, AuTaCHC(CH3)3), 1.79 (s, 1H, TaCHC(CH3)3), 1.75 (s, 9H, AuTaCHC(CH3)3), 1.56 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 6H, CH(CH3)2), 1.50–1.43 (m, 15H, TaCH2C(CH3)3 and CH(CH3)2), 1.34 (s, 9H, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 1.12–1.05 (m, 21H, TaCHC(CH3)3, and 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.01 (d, 2J1H–1H = 13.4 Hz, 1H, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 0.66 (s, 2H, TaCH2C(CH3)3), −0.34 (d, 2J1H–1H = 13.4 Hz, 1H, TaCH2C(CH3)3). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, toluene-d8, 253 K) δ ppm 229.51 (s, 1C, TaCHC(CH3)3), 202.23 (s, 1C, AuCNHC), 167.59 (s, 1C, AuTaCHC(CH3)3), 145.00 (s, 2C, 2 CAriPr), 144.78 (s, 2C, 2 CAriPr), 134.60 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.77 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.27 (s, 2C, 2 metaCHAr), 124.09 (s, 2C, 2 metaCHAr), 122.79 (s, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 103.27 (s, 1C, 1 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 92.45 (s, 1C, 1 TaCH2C(CH3)3), 46.83 (s, 1C, AuTaCHC(CH3)3), 43.66 (s, 1C, TaCHC(CH3)3), 38.15 (s, 3C, TaCHC(CH3)3), 35.38 (s, 3C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 35.06 (s, 3C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 34.94 (s, 3C, AuTaCHC(CH3)3), 34.39 (s, 1C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 34.01 (s, 1C, TaCH2C(CH3)3), 28.65 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.38 (s, 2C, 2 CH3iPr), 24.18 (s, 2C, 2 CH3iPr), 24.01 (s, 2C, 2 CHiPr), 23.91 (s, 2C, 2 CH3iPr). Anal. calcd for C47H78AuN2Ta: C, 53.81; H, 7.49; N, 2.67. Found: C, 53.83; H, 7.51; N, 2.63.

Synthesis of [Cu(C(CO)tBu)(IPr)] (4-Cu)

A solution of 2-Cu (100 mg, 0.11 mmol) in pentane (5 mL) was cooled to −80 °C with an acetone/liquid nitrogen bath and then exposed to a CO2 atmosphere (0.78 bar, 70.5 mL headspace, 0.22 mmol, 2 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 10 min at this temperature and then for 1 h at room temperature. The orange color of the starting product disappears, and a white precipitate was formed, which was then filtered, washed with pentane (3 × 2 mL), and dried in vacuum to give product 4 as a white solid (29 mg, 48% yield). Crystals of 4 suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained by slow recrystallization of a saturated toluene solution of 4 at −40 °C over a period of 16 h. 1H NMR (500 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.21 (t, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.07 (d, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.27 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH-N), 2.60 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.7 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.44 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.15 (s, 9H, CuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 1.08 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 183.83 (s, 1C, CuCNHC), 169.89 (s, 1C, CuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 145.80 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 135.11 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.64 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.28 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 122.25 (s, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 36.67 (s, 3C, CuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 32.19 (s, 1C, CuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 29.04 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.91 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.39 (s, 1C, CuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 23.94 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr). DRIFT (293 K, cm–1) ν = 3163 (s), 3138 (s), 2961 (s), 2891 (s), 2868 (s), 2012 (s, νCC=O), 1469 (s), 1404 (s), 1384 (s), 1364 (s), 1355 (s), 1327 (s), 1211 (s), 1179 (s), 1060 (s), 946 (s). Anal. calcd for C33H45CuN2O: C, 72.16; H, 8.26; N, 5.10. Found: C, 70.00; H, 8.06; N, 5.01.

Synthesis of [Ag(C(CO)tBu)(IPr)] (4-Ag)

A solution of 2-Ag (100 mg, 0.104 mmol) in pentane (5 mL) was cooled to −80 °C and then exposed to a CO2 atmosphere (73 mbar, 70.5 mL headspace, 0.208 mmol, 2 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 10 min at this temperature and then for 1 h at room temperature. The orange color of the starting product disappears, and a white precipitate was formed, which was then filtered, washed with pentane (3 × 2 mL), and dried in vacuum to give product 4-Ag as a white solid (29 mg, 49% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, THF-d8, 298 K) δ ppm 7.58 (d, 3J1H–1H = 1.1 Hz, 2H, N–CH=CH–N), 7.47 (t, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.34 (d, 3J1H–1H = 7.8 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 2.65 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.30 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.23 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2). 0.73 (s, 9H, AgC(CO)C(CH3)3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.24–7.14 (m, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.04 (d, 3J1H–1H = 7.7 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.31 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH-N), 2.53 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.37 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.21 (s, 9H, AgC(CO)C(CH3)3), 1.05 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, THF-d8, 298 K) δ ppm 189.20 (d, 1J13C–109Ag = 192.2 Hz and d, 1J13C–107Ag = 167.5 Hz, 1C, AgCNHC), 169.38 (d, 2J13C–109Ag = 2J13C–107Ag = 3.3 Hz, 1C, AgC(CO)C(CH3)3), 146.83 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 136.50 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 131.12 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.95 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 124.79 (d, 3J13C–109Ag = 3J13C–107Ag = 5.2 Hz, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 37.17 (d, 3J13C–109Ag = 3J13C–107Ag = 3.9, 3C, AgC(CO)C(CH3)3), 32.20 (d, 2J13C–109Ag = 2J13C–107Ag = 6.2, 1C, AgC(CO)C(CH3)3), 29.75 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 25.12 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.33 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 23.70 (d, 1J13C–109Ag = 121.78 Hz and d, 1J13C–107Ag = 104.62 Hz 1C, AgC(CO)C(CH3)3). DRIFT (293 K, cm–1) ν = 3165 (s), 3141 (s), 2962 (s), 2890 (s), 2868 (s), 2016 (s, νCC=O), 1593 (s), 1469 (s), 1456 (s), 1406 (s), 1384 (s), 1363 (s), 1355 (s), 1328 (s), 1211 (s), 1178 (s), 1115 (s), 1102 (s), 1056 (s), 936 (s). Anal. calcd for C33H45AgN2O: C, 66.77; H, 7.64; N, 4.72. Found: C, 66.33; H, 7.60; N, 4.55.

Synthesis of [Au(C(CO)tBu)(IPr)] (4-Au)

A solution of 2-Au (100 mg, 0.095 mmol) in pentane (5 mL) was cooled to −80 °C and then exposed to a CO2 atmosphere (67 mbar, 70.5 mL headspace, 0.20 mmol, 2 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 10 min at this temperature and then for 1 h at room temperature. The orange/brown color of the starting product disappears, and a white precipitate was formed, which was then filtered, washed with pentane (3 × 2 mL), and dried in vacuum to give a white solid (69 mg). The yield of the reaction was estimated by1H NMR from this solid using durene as an internal standard (77%), since one unidentified impurity cocrystallized with the final product. Unfortunately, despite numerous attempts, we failed to remove this impurity by fractional recrystallizations. 1H NMR (500 MHz, THF-d8, 298 K) δ ppm 7.53 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH–N), 7.45 (t, 3J1H-1H = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.31 (d, = 7.8 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 2.68 (hept, 3J1H-1H = 6.9 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.36 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.22 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.9 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 0.72 (s, 9H, AuC(CO)C(CH3)3). 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 298 K) δ ppm 7.26–7.11 (m, 2H, 2 para CHAr), 7.05 (d, 3J1H–1H = 7.7 Hz, 4H, 4 meta CHAr), 6.26 (s, 2H, N–CH=CH-N), 2.60 (hept, 3J1H–1H = 6.7 Hz, 4H, 4 CH(CH3)2), 1.48 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2), 1.16 (s, 9H, AuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 1.07 (d, 3J1H–1H = 6.8 Hz, 12H, 2 CH(CH3)2). 13C{1H}-NMR (126 MHz, THF-d8, 298 K) δ ppm 193.39 (s, 1C, AuCNHC), 181.19 (s, 1C, AuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 146.84 (s, 4C, 4 CAriPr), 136.11 (s, 2C, 2 CArN), 130.99 (s, 2C, 2 paraCHAr), 124.80 (s, 4C, 4 metaCHAr), 124.30 (s, 2C, N–CH=CH–N), 39.71 (s, 1C, AuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 36.45 (s, 3C, AuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 32.00 (s, 1C, AuC(CO)C(CH3)3), 29.80 (s, 4C, 4 CHiPr), 24.84 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr), 24.40 (s, 4C, 4 CH3iPr). DRIFT (293 K, cm–1) ν = 3166 (s), 3142 (s), 2960 (s), 2894 (s), 2867 (s), 2027 (s, νCC=O), 1552 (s), 1470 (s), 1414 (s), 1384 (s), 1364 (s), 1357 (s), 1328 (s), 1315 (s), 1257 (s), 1232 (s), 1180 (s), 1117 (s), 1060 (s), 947 (s), 936 (s), 866 (s), 805 (s), 768 (s).

Reactivity of Compound 1 with CO2

A solution of complex 1 (100 mg, 0.16 mmol) in pentane (5 mL) was exposed to a CO2 atmosphere (114 mbar, 70.5 mL headspace, 0.33 mmol, 2 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 90 min. A yellow precipitate formed, which was then filtered, washed with pentane (3 × 2 mL), and dried under vacuum to yield a yellow pale powder (60 mg). This solid appeared to be insoluble in pentane (as well as in C6D6). It was subsequently analyzed by 1H NMR in THF-d8 (see Figure S64), revealing the formation of a mixture of unknown diamagnetic compounds. The supernatant solution was also evaporated under vacuum and analyzed by 1H NMR, revealing the full consumption of complex 1 in this reaction (see Figure S65).

Acknowledgments

L. M. is a senior member of the “Institut Universitaire de France”. Anne Baudouin and Emmanuel Chefdeville are acknowledged for their help in acquiring the NMR data.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.4c02172.

NMR and DRIFT spectra (Figures S1–S66); XRD, projection of the reciprocical space (Figures S67–S70); and computational data (Figures DFT-1–DFT-9); crystallographic parameters (Tables S1, S2); relative stability (Table S3) (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funded by the European Union (ERC, DUO 101 041 762). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. The computational work was performed using the HPC resources from CALMIP (Grant 2016-p0833).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author Status

A CC-BY public copyright license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) has been applied by the authors to the present document and will be applied to all subsequent versions up to the Author Accepted Manuscript arising from this submission, in accordance with the grant’s open access conditions.

Supplementary Material

References

- Navarro M.; Bourissou D.. π-Alkene/Alkyne and Carbene Complexes of Gold(I) Stabilized by Chelating Ligands. In Advances in Organometallic Chemistry; Academic Press, 2021; Vol. 76, pp. 101–144.. DOI: 10.1016/bs.adomc.2021.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehara J.; Watson B. T.; Noonikara-Poyil A.; Zacharias A. O.; Roithová J.; Rasika Dias H. V. Binding Interactions in Copper, Silver and Gold π-Complexes. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2022, 28 (13), e202103984 10.1002/chem.202103984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M.; Toledo A.; Mallet-Ladeira S.; Sosa Carrizo E. D.; Miqueu K.; Bourissou D. Versatility and Adaptative Behaviour of the P^N Chelating Ligand MeDalphos within Gold(I) π Complexes. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (10), 2750–2758. 10.1039/C9SC06398F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J.; Szalóki G.; Sosa Carrizo E. D.; Saffon-Merceron N.; Miqueu K.; Bourissou D. Gold(III) π-Allyl Complexes. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (4), 1511–1515. 10.1002/anie.201912314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. S.; Harlow R. L.; Whitney J. F. Copper(I)-Olefin Complexes. Support for the Proposed Role of Copper in the Ethylene Effect in Plants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105 (11), 3522–3527. 10.1021/ja00349a026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dias H. V. R.; Wu J. Structurally Characterized Coinage-Metal–Ethylene Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem 2008, 2008 (4), 509–522. 10.1002/EJIC.200701055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dias H. V. R.; Lovely C. J. Carbonyl and Olefin Adducts of Coinage Metals Supported by Poly(Pyrazolyl)Borate and Poly(Pyrazoly)Alkane Ligands and Silver Mediated Atom Transfer Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108 (8), 3223–3238. 10.1021/cr078362d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.; Zhai X. Y.; Zhao L. Mechanistic Insights into Multisilver-Mediated Synergistic Activation of Terminal Alkynes. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62 (4), 1414–1422. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M.; Toledo A.; Joost M.; Amgoune A.; Mallet-Ladeira S.; Bourissou D. π Complexes of P^P and P^N Chelated Gold(I). Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (55), 7974–7977. 10.1039/C9CC04266K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motloch P.; Jašík J.; Roithová J. Gold(I) and Silver(I) π-Complexes with Unsaturated Hydrocarbons. Organometallics 2021, 40 (10), 1492–1502. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deolka S.; Rivada-Wheelaghan O.; Aristizábal S. L.; Fayzullin R. R.; Pal S.; Nozaki K.; Khaskin E.; Khusnutdinova J. R. Metal-Metal Cooperative Bond Activation by Heterobimetallic Alkyl, Aryl, and Acetylide PtII/CuIcomplexes. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (21), 5494–5502. 10.1039/D0SC00646G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias A. O.; Mao J. X.; Nam K.; Dias H. V. R. Copper(I) and Silver(I) Chemistry of Vinyltrifluoroborate Supported by a Bis(Pyrazolyl)Methane Ligand. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50 (22), 7621–7632. 10.1039/D1DT00974E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonikara-Poyil A.; Cui H.; Yakovenko A. A.; Stephens P. W.; Lin R.-B.; Wang B.; Chen B.; Dias H. V. R. A Molecular Compound for Highly Selective Purification of Ethylene. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133 (52), 27390–27394. 10.1002/ange.202109338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambrier I.; Rocchigiani L.; Hughes D. L.; Budzelaar P. M. H.; Bochmann M. Thermally Stable Gold(III) Alkene and Alkyne Complexes: Synthesis, Structures, and Assessment of the Trans-Influence on Gold–Ligand Bond Enthalpies. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24 (44), 11467–11474. 10.1002/CHEM.201802160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchigiani L.; Fernandez-Cestau J.; Agonigi G.; Chambrier I.; Budzelaar P. H. M.; Bochmann M. Gold(III) Alkyne Complexes: Bonding and Reaction Pathways. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (44), 13861–13865. 10.1002/anie.201708640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langseth E.; Scheuermann M. L.; Balcells D.; Kaminsky W.; Goldberg K. I.; Eisenstein O.; Heyn R. H.; Tilset M. Generation and Structural Characterization of a Gold(III) Alkene Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (6), 1660–1663. 10.1002/anie.201209140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savjani N.; Roşca D. A.; Schormann M.; Bochmann M. Gold(III) Olefin Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52 (3), 874–877. 10.1002/anie.201208356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praveen C. Carbophilic Activation of π-Systems via Gold Coordination: Towards Regioselective Access of Intermolecular Addition Products. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 392, 1–34. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X.-T.; Yang F.; Zhang T.-T.; Liu Y.-F.; Liu S.-Y.; Su T.-F.; Lv D.-C.; Shen W.-B. Recent Progress in N-Heterocyclic Carbene Gold-Catalyzed Reactions of Alkynes Involving Oxidation/Amination/Cycloaddition. Catalysts 2020, 10 (3), 350. 10.3390/catal10030350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Carrillo V.; Echavarren A. M. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Intermolecular [2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Alkynes with Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (27), 9292–9294. 10.1021/ja104177w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanini M.; Cataffo A.; Echavarren A. M. Synthesis of Cyclobutanones by Gold(I)-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloaddition of Ynol Ethers with Alkenes. Org. Lett. 2021, 23 (22), 8989–8993. 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoulet M.; Thillaye du Boullay O.; Amgoune A.; Bourissou D. Gold(I)/Gold(III) Catalysis That Merges Oxidative Addition and π-Alkene Activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (38), 16625–16630. 10.1002/anie.202006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi A. S. K.; Lauterbach T.; Nösel P.; Vilhelmsen M. H.; Rudolph M.; Rominger F. Dual Gold Catalysis: σ,π-Propyne Acetylide and Hydroxyl-Bridged Digold Complexes as Easy-to-Prepare and Easy-to-Handle Precatalysts. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2013, 19 (3), 1058–1065. 10.1002/chem.201203010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes Dos Santos Comprido L.; Klein J. E. M. N.; Knizia G.; Kästner J.; Hashmi A. S. K. Gold(I) Vinylidene Complexes as Reactive Intermediates and Their Tendency to π-Backbond. Chem. - A Eur. J. 2016, 22 (9), 2892–2895. 10.1002/chem.201504511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi A. S. K. Gold-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 3180–3211. 10.1021/cr000436x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürstner A. From Understanding to Prediction: Gold- and Platinum-Based Π-Acid Catalysis for Target Oriented Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47 (3), 925–938. 10.1021/ar4001789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. C. Gold π-Complexes as Model Intermediates in Gold Catalysis. Top. Curr. Chem. 2014, 357, 133–166. 10.1007/128_2014_593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J.; Vesseur D.; Tabey A.; Mallet-Ladeira S.; Miqueu K.; Bourissou D. Au(I)/Au(III) Catalytic Allylation Involving π-Allyl Au(III) Complexes. ACS Catal. 2022, 12 (2), 993–1003. 10.1021/acscatal.1c04580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Praveen C.; Szafert S. Homogeneous Gold Catalysis for Regioselective Carbocyclization of Alkynyl Precursors. ChemPluschem 2023, 88 (7), e202300202 10.1002/cplu.202300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi A. S. K.; Hutchings G. J. Gold Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45 (47), 7896–7936. 10.1002/anie.200602454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y.-B.; Luo Z.; Wang Y.; Gao J.-M.; Zhang L. Au-Catalyzed Intermolecular [2 + 2] Cycloadditions between Chloroalkynes and Unactivated Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (17), 5860–5865. 10.1021/jacs.8b01813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Orbe M. E.; Amenós L.; Kirillova M. S.; Wang Y.; López-Carrillo V.; Maseras F.; Echavarren A. M. Cyclobutene vs 1,3-Diene Formation in the Gold-Catalyzed Reaction of Alkynes with Alkenes: The Complete Mechanistic Picture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (30), 10302–10311. 10.1021/jacs.7b03005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweis R. F.; Schramm M. P.; Kozmin S. A. Silver-Catalyzed [2 + 2] Cycloadditions of Siloxy Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (24), 7442–7443. 10.1021/ja048251l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunschweig H.; Radacki K.; Shang R. Side-on Coordination of Boryl and Borylene Complexes to Cationic Coinage Metal Fragments. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6 (5), 2989–2996. 10.1039/C5SC00211G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriedo G. A.; Riera V.; Sánchez G.; Solans X. Synthesis of New Heteronuclear Complexes with Bridging Carbyne Ligands between Tungsten and Gold. X-Ray Crystal Structure of [AuW(μ-CC6H4Me-4)(CO)2(Bipy)(C6F5)Br]. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1988, 7, 1957–1962. 10.1039/DT9880001957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onn C. S.; Hill A. F.; Olding A. Metal Coordination of Phosphoniocarbynes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49 (36), 12731–12741. 10.1039/D0DT02737E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzano R. A.; Hill A. F. Fluorocarbyne Complexes via Electrophilic Fluorination of Carbido Ligands. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14 (14), 3776–3781. 10.1039/D3SC00261F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark G. R.; Cochrane C. M.; Roper W. R.; Wright L. J. The Interaction of an Osmium-Carbon Triple Bond with Copper(I), Silver(I) and Gold(I) to Give Mixed Dimetallocyclopropene Species and the Structures of Os(AgCl) (CR) Cl(CO) (PPh3)2. J. Organomet. Chem. 1980, 199 (2), C35–C38. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)83865-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Li Y.; Shao Y.; Hua Y.; Zhang H.; Lin Y. M.; Xia H. Reactions of Cyclic Osmacarbyne with Coinage Metal Complexes. Organometallics 2018, 37 (11), 1788–1794. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borren E. S.; Hill A. F.; Shang R.; Sharma M.; Willis A. C. A Golden Ring: Molecular Gold Carbido Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (13), 4942–4945. 10.1021/ja400128h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frogley B. J.; Hill A. F.; Onn C. S. Auriferous Alkynylselenolatoalkylidynes. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48 (31), 11715–11723. 10.1039/C9DT02314C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N. A.; Kong R. Y.; White A. J. P.; Crimmin M. R. Group 11 Borataalkene Complexes: Models for Alkene Activation. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (21), 12013–12019. 10.1002/anie.202100919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A.; Wu L.; Lin Z.; Yamashita M. Isomerization of a Cis-(2-Borylalkenyl)Gold Complex via a Retro-1,2-Metalate Shift: Cleavage of a C–C/C–Si Bond Trans to a C–Au Bond. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (38), 21007–21013. 10.1002/anie.202108530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisofsky G. K.; Rojales K.; Su X.; Bartholome T. A.; Molino A.; Kaur A.; Wilson D. J. D.; Dutton J. L.; Martin C. D. Ligation of Boratabenzene and 9-Borataphenanthrene to Coinage Metals. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60 (24), 18981–18989. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c02800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Daniliuc C. G.; Kehr G.; Erker G. Bora-Alkenes: Metal Coordination and Reactions with BH-Boranes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2023, 29 (41), e202301044 10.1002/CHEM.202301044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frogley B. J.; Hill A. F.; Watson L. J. New Binding Modes for CSe: Coinage Metal Coordination to a Tungsten Selenocarbonyl Complex. Dalton Trans 2019, 48 (33), 12598–12606. 10.1039/C9DT02958C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt L. K.; Dewhurst R. D.; Hill A. F.; Kong R. Y.; Nahon E. E.; Onn C. S. Heterobimetallic Μ2-Halocarbyne Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51 (32), 12080–12099. 10.1039/D2DT01558G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo Q.; Zhang H.; Hua Y.; Kang H.; Zhou X.; Lin X.; Chen Z.; Lin J.; Zhuo K.; Xia H. Constraint of a Ruthenium-Carbon Triple Bond to a Five-Membered Ring. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4 (6), 336–358. 10.1126/sciadv.aat0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrock R. R. High Oxidation State Multiple Metal-Carbon Bonds. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102 (1), 145–179. 10.1021/cr0103726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhorn H.; Tamm M. Well-Defined Alkyne Metathesis Catalysts: Developments and Recent Applications. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25 (13), 3190–3208. 10.1002/chem.201804511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürstner A.; Davies P. W. Alkyne Metathesis. Chem. Commun. 2005, 18, 2307–2320. 10.1039/b419143a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenberger L. J.; Schrock R. R. A Tantalum Carbyne Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97 (10), 2935. 10.1021/ja00843a072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld M. H. P.; Lohner P.; Nijkamp M. G.; Grove D. M.; Veldman N.; Spek A. L.; Pfeffer M.; Van Koten G. A Novel Synthetic Route to Tantalum-Zinc Neophylidyne Complexes Stabilized by Ortho-Chelating Arylamine Ligands; the X-Ray Structure of [TaCl2(μ-C6H4CH2NMe2–2)(μ-CCMe2 Ph)ZnCl(THF)]. Chem. - Eur. J. 1997, 3 (5), 817–822. 10.1002/chem.19970030522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gal A. W.; Van Der Heijden H. Synthesis and X-Ray Crystal Structure of the Trimetallic Neopentylidyne Complex [{Cl2(MeOCH2CH2OMe)Ta(μ-CCMe 3)}2Zn(μ-Cl)2]. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1983, 8, 420–422. 10.1039/C39830000420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbenhuis H. C. L.; Feiken N.; Haarman H. F.; Grove D. M.; Horn E.; Spek A. L.; Pfeffer M.; van Koten G. A Bimetallic Tantalum-Zinc Complex with an Ancillary Aryldiamine Ligand as Precursor for a Reactive Alkylidyne Species: Alkylidyne-Mediated C-H Activation and a Palladium-Mediated Alkylidyne Functionalization. Organometallics 1993, 12 (6), 2227–2235. 10.1021/om00030a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lohner P.; Fischer J.; Pfeffer M. Synthesis and Reactivity of Early-Late Heterobimetallic Complexes Displaying a Η2-Tantalum-Alkylidene to Palladium Interaction. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2002, 330 (1), 220–228. 10.1016/S0020-1693(01)00829-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachguar A.; Pichugov A. V.; Neumann T.; Dubrawski Z.; Camp C. Cooperative Activation of Carbon-Hydrogen Bonds by Heterobimetallic Systems. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 1393–1409. 10.1039/D3DT03571A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R.; Wang X. F.; Hu C.; Liu L. L. Synthesis and Reactivity of Copper Carbyne Anion Complexes. Nat. Synth. 2023, 2 (4), 357–363. 10.1038/s44160-022-00225-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C.; Wang X. F.; Wei R.; Hu C.; Ruiz D. A.; Chang X. Y.; Liu L. L. Crystalline Monometal-Substituted Free Carbenes. Chem 2022, 8 (8), 2278–2289. 10.1016/j.chempr.2022.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez M. A.; García M. E.; García-Vivó D.; Martínez M. E.; Ruiz M. A. Binuclear Carbyne and Ketenyl Derivatives of the Alkyl-Bridged Complexes [Mo2(Η5-C5H5) 2(μ-CH2R)(μ-PCy2)(CO)2] (R = H, Ph). Organometallics 2011, 30 (8), 2189–2199. 10.1021/om1011819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R.; Wang X. F.; Ruiz D. A.; Liu L. L. Stable Ketenyl Anions via Ligand Exchange at an Anionic Carbon as Powerful Synthons**. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (15), e202219211 10.1002/anie.202219211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörges M.; Krischer F.; Gessner V. H. Transition Metal–Free Ketene Formation from Carbon Monoxide through Isolable Ketenyl Anions. Science 2022, 378 (6626), 1331–1336. 10.1126/science.ade4563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G. A.; Agapie T. Terminal Mo Carbide and Carbyne Reactivity: H2Cleavage, B-C Bond Activation, and C-C Coupling. Organometallics 2021, 40 (16), 2881–2887. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann C.; Thiem P.; Wanitschke D.; Hüttenschmidt M.; Romischke J.; Villinger A.; Seidel W. W. Migratory Insertion of Isocyanide into a Ketenyl-Tungsten Bond as Key Step in Cyclization Reactions. Chem. Sci. 2021, 13 (1), 123–132. 10.1039/D1SC06149F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.; Wang T.; Qu Z. W.; Grimme S.; Stephan D. W. Reactions of a Dilithiomethane with CO and N2O: An Avenue to an Anionic Ketene and a Hexafunctionalized Benzene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (48), 25281–25285. 10.1002/anie.202111486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss J. A.; Bailey G. A.; Oppenheim J.; Vandervelde D. G.; Goddard W. A.; Agapie T. CO Coupling Chemistry of a Terminal Mo Carbide: Sequential Addition of Proton, Hydride, and CO Releases Ethenone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (39), 15664–15674. 10.1021/jacs.9b07743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro S.; Himo F. Mechanism of the Kinugasa Reaction Revisited. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86 (15), 10665–10671. 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malig T. C.; Yu D.; Hein J. E. A Revised Mechanism for the Kinugasa Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (29), 9167–9173. 10.1021/jacs.8b04635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torelli A.; Choi E. S.; Dupeux A.; Perner M. N.; Lautens M. Stereoselective Kinugasa/Aldol Cyclization: Synthesis of Enantioenriched Spirocyclic β-Lactams. Org. Lett. 2023, 25 (47), 8520–8525. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c03534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Jiang L.; Liang H.; Fan H. Mechanism of Silver-Catalyzed[2 + 2] Cycloaddition between Siloxy-Alkynes and Carbonyl Compound: A Silylium Ion Migration Approach. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 41 (11), 4327–4337. 10.6023/cjoc202106038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R.; Quadrelli E. A.; Camp C. Lability of Ta-NHC Adducts as a Synthetic Route towards Heterobimetallic Ta/Rh Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49 (10), 3120–3128. 10.1039/D0DT00344A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle S.; Petit J.; Falconer R. L.; Hérault V.; Jeanneau E.; Thieuleux C.; Camp C. Reactivity of Tantalum/Iridium and Hafnium/Iridium Alkyl Hydrides with Alkyl Lithium Reagents: Nucleophilic Addition, Alpha-H Abstraction, or Hydride Deprotonation?. Organometallics 2022, 41 (13), 1675–1687. 10.1021/acs.organomet.2c00158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle S.; Jabbour R.; Schiltz P.; Berruyer P.; Todorova T. K.; Veyre L.; Gajan D.; Lesage A.; Thieuleux C.; Camp C. Metal–Metal Synergy in Well-Defined Surface Tantalum–Iridium Heterobimetallic Catalysts for H/D Exchange Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (49), 19321–19335. 10.1021/jacs.9b08311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R.; Moneuse R.; Petit J.; Pavard P.-A.-A.; Dardun V.; Rivat M.; Schiltz P.; Solari M.; Jeanneau E.; Veyre L.; et al. Early/Late Heterobimetallic Tantalum/Rhodium Species Assembled Through a Novel Bifunctional NHC-OH Ligand. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24 (17), 4361–4370. 10.1002/chem.201705507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle S.; Jabbour R.; Del Rosal I.; Maron L.; Fonda E.; Veyre L.; Gajan D.; Lesage A.; Thieuleux C.; Camp C. Stepwise Construction of Silica-Supported Tantalum/Iridium Heteropolymetallic Catalysts Using Surface Organometallic Chemistry. J. Catal. 2020, 392, 287–301. 10.1016/j.jcat.2020.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camp C.; Toniolo D.; Andrez J.; Pécaut J.; Mazzanti M. A Versatile Route to Homo- and Hetero-Bimetallic 5f-5f and 3d-5f Complexes Supported by a Redox Active Ligand Framework. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46 (34), 11145. 10.1039/C7DT01993A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S.; Karunananda M. K.; Bagherzadeh S.; Jayarathne U.; Parmelee S. R.; Waldhart G. W.; Mankad N. P. Synthesis and Characterization of Heterobimetallic Complexes with Direct Cu-m Bonds (m = Cr, Mn, Co, Mo, Ru, w) Supported by N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands: A Toolkit for Catalytic Reaction Discovery. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53 (20), 11307–11315. 10.1021/ic5019778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C. Z.; Del Rosal I.; Boreen M. A.; Ouellette E. T.; Russo D. R.; Maron L.; Arnold J.; Camp C. A Versatile Strategy for the Formation of Hydride-Bridged Actinide-Iridium Multimetallics. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14 (4), 861–868. 10.1039/D2SC04903A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C. P.; Raynaud C.; Andersen R. A.; Copéret C.; Eisenstein O. Carbon-13 NMR Chemical Shift: A Descriptor for Electronic Structure and Reactivity of Organometallic Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52 (8), 2278–2289. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortman G. C.; Slawin A. M. Z.; Nolan S. P. A Versatile Cuprous Synthon: [Cu(IPr)(OH)] (IPr = 1,3 Bis(Diisopropylphenyl)Imidazol-2-Ylidene). Organometallics 2010, 29 (17), 3966–3972. 10.1021/om100733n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLain S. J.; Wood C. D.; Messerle L. W.; Schrock R. R.; Hollander F. J.; Youngs W. J.; Churchill M. R. Multiple Metal-Carbon Bonds. 10.1 Thermally Stable Tantalum Alkylidyne Complexes and the Crystal Structure of Ta(η-C5Me5)(CPh)(PMe3)2Cl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100 (18), 5962–5964. 10.1021/ja00486a069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanwick P. E.; Ogilvy A. E.; Rothwell I. P. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Properties of Tantalum 1/4-Alkylldyne Compounds Containing Bulky Aryloxide Ligands: X-Ray Structures of The Asymmetric Derivatives (Me2SiCH2)2ta(1/4-CSiMe3)2Ta(Ch2SiMe3)(OAr-2,6-Ph2) and (Me2SiCH2)2Ta(CH-CSiMe3)2Ta(OAr-2,6-t-Bu2)2(. Organometallics 1987, 6 (1), 73–80. 10.1021/om00144a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill M. R.; Holl F. J. Crystal and molecular structure of a tantalum-alkylidene complex, bis(.eta.5-cyclopentadienyl)chloro(neopentylidene)tantalum. Inorg. Chem. 1978, 17 (7), 1957–1962. 10.1021/ic50185a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz A. J.; Williams J. M.; Schröck R. R.; Rupprecht G. A.; Fellmann J. D. Interaction of Hydrogen and Hydrocarbons with Transition Metals. Neutron Diffraction Evidence for an Activated Carbon-Hydrogen Bond in an Electron-Deficient Tantalum-Neopentylidene Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101 (6), 1593–1595. 10.1021/ja00500a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abbenhuis H. C. L.; Feiken N.; Grove D. M.; Jastrzebski J. T. B. H.; Kooijman H.; van der Sluis P.; Smeets W. J. J.; Spek A. L.; van Koten G. Use of an Aryldiamine Pincer Ligand in the Study of Tantalum Alkylidene-Centered Reactivity: Tantalum-Mediated Alkene Synthesis via Reductive Rearrangements and Wittig-Type Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114 (25), 9773–9781. 10.1021/ja00051a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayarathne U.; Mazzacano T. J.; Bagherzadeh S.; Mankad N. P. Heterobimetallic Complexes with Polar, Unsupported Cu-Fe and Zn-Fe Bonds Stabilized by N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Organometallics 2013, 32 (14), 3986–3992. 10.1021/om400471u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhmutov V. I.; Vorontsov E. V.; Bakhmutova E. V.; Boni G.; Moise C. Tantalum-Gold and Tantalum-Copper Trihydride Complexes Cp’2TaH3MPPh3[PF6] (Cp’ = C5H4C(CH3)3). Structure Determination From1H T1 Relaxation Studies. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 38 (6), 1121–1125. 10.1021/ic980765w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pätow R.; Isaac I. Syntheses and Crystal Structures of Novel Heterobimetallic Tantalum Coin MetalChalcogenido Clusters. Zeitschrift für Anorg. Und Allg. Chemie 2002, 628, 1279–1288. 10.1002/1521-3749. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. Q.; Morgan H. W. T.; Shu C. C.; McGrady J. E.; Sun Z. M. Synthesis and Characterization of Ternary Clusters Containing the [As16]10-Anion, [MM′As16]4-(M = Nb or Ta; M′= Cu or Ag). Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61 (10), 4421–4427. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.1c03940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiola M. L.; Buss J. A. Accessing Ta/Cu Architectures via Metal-Metal Salt Metatheses: Heterobimetallic C–H Bond Activation Affords μ-Hydrides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202311721 10.1002/anie.202311721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauling L. Atomic Radii and Interatomic Distances in Metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69 (3), 542–553. 10.1021/ja01195a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero B.; Gómez V.; Platero-Prats A. E.; Revés M.; Echeverría J.; Cremades E.; Barragán F.; Alvarez S.; et al. Covalent Radii Revisited. Dalton Trans. 2008, 44 (21), 2832. 10.1039/b801115j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Frémont P.; Scott N. M.; Stevens E. D.; Ramnial T.; Lightbody O. C.; Macdonald C. L. B. B.; Clyburne J. A. C. C.; Abernethy C. D.; Nolan S. P. Synthesis of Well-Defined N-Heterocyclic Carbene Silver(I) Complexes. Organometallics 2005, 24 (26), 6301–6309. 10.1021/om050735i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tzouras N. V.; Saab M.; Janssens W.; Cauwenbergh T.; Van Hecke K.; Nahra F.; Nolan S. P. Simple Synthetic Routes to N-Heterocyclic Carbene Gold(I)–Aryl Complexes: Expanded Scope and Reactivity. Chem. - Eur. J. 2020, 26 (24), 5541–5551. 10.1002/chem.202000876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakarawet K.; Davis-Gilbert Z. W.; Harstad S. R.; Young V. G.; Long J. R.; Ellis J. E. Ta(CNDipp)6: An Isocyanide Analogue of Hexacarbonyltantalum(0). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (35), 10577–10581. 10.1002/anie.201706323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Z. L.; Morton L. A. Transition Metal Alkylidene Complexes. Pathways in Their Formation and Tautomerization between Bis-Alkylidenes and Alkyl Alkylidynes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696 (25), 3924–3934. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2011.06.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morton L. A.; Wang R.; Yu X.; Campana C. F.; Guzei I. A.; Yap G. P. A.; Xue Z. L. Tungsten Alkyl Alkylidyne and Bis-Alkylidene Complexes. Preparation and Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies of Their Unusual Exchanges. Organometallics 2006, 25 (2), 427–434. 10.1021/om050745j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morton L. A.; Zhang X. H.; Wang R.; Lin Z.; Wu Y. D.; Xue Z. L. An Unusual Exchange between Alkylidyne Alkyl and Bis(Alkylidene) Tungsten Complexes Promoted by Phosphine Coordination: Kinetic, Thermodynamic, and Theoretical Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126 (33), 10208–10209. 10.1021/ja0467263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan B. A.; Xue Z. L. Reaction of a Tungsten Alkylidyne Complex with a Chelating Diphosphine. α-Hydrogen Migration in the Intermediates and Formation of an Alkyl Alkylidene Alkylidyne Complex. Organometallics 2009, 28 (5), 1295–1302. 10.1021/om8010917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud R.; Rendón N.; Blanc F.; Solans-Monfort X.; Copéret C.; Eisenstein O. Metal Fragment Isomerisation upon Grafting a D2ML4 Perhydrocarbyl Os Complex on a Silica Surface: Origin and Consequence. Dalton Trans. 2009, 30, 5879–5886. 10.1039/b901669d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callens E.; Abou-Hamad E.; Riache N.; Basset J. M. Direct Observation of Supported W Bis-Methylidene from Supported W-Methyl/Methylidyne Species. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50 (31), 3982–3985. 10.1039/C4CC00286E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellmann J. D.; Rupprecht G. A.; Wood C. D.; Schrock R. R. Multiple Metal-Carbon Bonds. 11.1 Bisneopentylidene Complexes of Niobium and Tantalum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100 (18), 5964–5966. 10.1021/ja00486a070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giarrusso C. P.; Zeil D. V.; Blair V. L. Catalytic Exploration of NHC-Ag(i)HMDS Complexes for the Hydroboration and Hydrosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52 (23), 7828–7835. 10.1039/D3DT01042B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbenhuis H. C. L.; Rietveld M. H. P.; Haarman H. F.; Hogerheide M. P.; Spek A. L.; van Koten G. Configurational Preferences and Alkylidene-Centered Reactivity of Tantalum Alkoxide Complexes Containing an Aryldiamine Spectator Ligand. Organometallics 1994, 13 (8), 3259–3268. 10.1021/om00020a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaPointe R. E.; Wolczanski P. T.; Van Duyne G. D. Tantalum Organometallics Containing Bulky Oxy Donors: Utilization of Tri-Tert-Butylsiloxide and 9-Oxytriptycene. Organometallics 1985, 4 (10), 1810–1818. 10.1021/om00129a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrock R. R.; Fellmann J. D. Multiple Metal-Carbon Bonds. 8. Preparation, Characterization, and Mechanism of Formation of the Tantalum and Niobium Neopentylidene Complexes, M(CH2CMe3)3(CHCMe3). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100 (11), 3359–3370. 10.1021/ja00479a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chabanas M.; Quadrelli E. A.; Fenet B.; Copéret C.; Thivolle-Cazat J.; Basset J.-M.; Lesage A.; Emsley L. Molecular Insight Into Surface Organometallic Chemistry Through the Combined Use of 2D HETCOR Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy and Silsesquioxane Analogues. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40 (23), 4493–4496. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boncella J. M.; Cajigal M. L.; Abboud K. A. Competition between π Donation and α-C–H Agostic Interactions in Complexes of the Type Tp‘Ta(CH- t -Bu)(X)(Y) (X = Halide; Y = Halide, NR 2, OR; Tp‘= Hydrotris(3,5-Dimethylpyrazolyl)Borate). Organometallics 1996, 15 (7), 1905–1912. 10.1021/om950836o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill M. R.; Youngs W. J. Crystal Structure and Molecular Geometry of Ta(: CHCMe3)2(Mesityl)(PMe3)2, a Bis(Alkylidene) Complex of Tantalum with Remarkably Obtuse Ta: C(.Alpha.)-C(.Beta.) Angles of 154.0(6) and 168.9(6).Degree. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18 (7), 1930–1935. 10.1021/ic50197a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stang P. J.; Roberts K. A. Generation and Trapping of Alkynolates from Alkynyl Tosylates: Formation of Siloxyalkynes and Ketenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108 (22), 7125–7127. 10.1021/ja00282a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Firl J.; Runge W. 13C-NMR Spectrum of Ketene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1973, 12 (8), 668–669. 10.1002/anie.197306681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]