Musculoskeletal symptoms of various types (neck pain, limb pain, low back pain, joint pain, chronic widespread pain) are a major reason for consultation in primary care. This article uses the example of low back pain because it is particularly common and there is a substantial evidence base for its management. The principles of management outlined are also applicable to non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms in general.

The increasing prevalence of musculoskeletal pain, including back pain, has been described as an epidemic. Pain complaints are usually self limiting, but if they become chronic the consequences are serious. These include the distress of patients and their families and consequences for employers in terms of sickness absence and for society as a whole in terms of welfare benefits and lost productivity. Many causes for musculoskeletal pain have been identified. Psychological and social factors have been shown to play a major role in exacerbating the biological substrate of pain by influencing pain perception and the development of chronic disability. This new understanding has led to a “biopsychosocial” model of back pain.

Research has also shown that there are many different reasons for patients to consult their doctor with pain—seeking cure or symptomatic relief, diagnostic clarification, reassurance, “legitimisation” of symptoms, or medical certification for work absence or to express distress, frustration, or anger. Doctors need to clarify which of these reasons apply to an individual and to respond appropriately.

Managing acute back pain

Most patients can be effectively managed with a combination of brief assessment and giving information, advice, analgesia, and appropriate reassurance. Minimal rest and an early return to work should be encouraged. Explanation and advice can be usefully supplemented with written material.

Doctors' tasks include not only the traditional provision of diagnosis, investigation, prescriptions, and sickness certificates but also giving accurate advice, information, and reassurance. Primary care and emergency department doctors are potentially powerful therapeutic agents and can provide effective immediate care, but they may also unintentionally promote progression to chronic pain. The risk of chronicity is reduced by

Excerpt from information booklet The Back Book*

It's your back

Backache is not a serious disease and it should not cripple you unless you let it. We have tried to show you the best way to deal with it. The important thing now is for you to get on with your life. How your backache affects you depends on how you react to the pain and what you do about it yourself.

There is no instant answer. You will have your ups and downs for a while—that is normal. But look at it this way

There are two types of sufferer

One who avoids activity, and one who copes

The avoider gets frightened by the pain and worries about the future

The avoider is afraid that hurting always means further damage—it doesn't

The avoider rests a lot and waits for the pain to get better

The coper knows that the pain will get better and does not fear the future

The coper carries on as normally as possible

The coper deals with the pain by being positive, staying active, or staying at work

*Roland M et al, Stationery Office, 2002.

Paying attention to the psychological aspects of symptom presentation

Avoiding unnecessary, excessive, or inappropriate investigation

Avoiding inconsistent care (which may cause patients to become overcautious)

Giving advice on preventing recurrence (such as by sensible lifting and avoiding excessive loads).

Research evidence supports a change of emphasis from treating symptoms to early prevention of factors that result in progression to chronicity. This has led to the development of new back pain management guidelines for both medical management and occupational health. The shift in emphasis from rest and immobilisation to active self management requires broadening the focus of the consultation from examination of symptoms alone to assessment, which includes patients' understanding of their pain and how they behave in response to it. The shift towards self directed pain management recasts the role of primary care doctor to the more rewarding one of guide or coach rather than a mere “mechanic.”

Factors associated with chronicity and outcome

Distress

Symptom awareness and concern

Depressive reactions; helplessness

Beliefs about pain and disability

Significance and controllability

Fears and misunderstandings about pain

Behavioural factors

Guarded movements and avoidance patterns

Coping style and strategies

Identify risk factors for chronicity

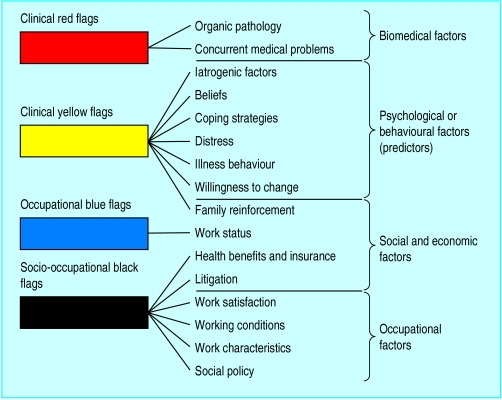

Guidelines for primary care management of acute back pain highlight the identification of risk factors for chronicity. A useful approach has been developed in New Zealand. It aims to involve all interested parties—patient, the patient's family, healthcare professionals, and, importantly, the patient's employer. Four groups of risk factors or “flags” for chronicity are accompanied by recommended assessment strategies, which include the use of screening questionnaires, a set of structured interview prompts, and a guide to behavioural management. The focus is on key psychological factors that favour chronicity:

The belief that back pain is due to progressive pathology

The belief that back pain is harmful or severely disabling

The belief that avoidance of activity will help recovery

A tendency to low mood and withdrawal from social interaction

The expectation that passive treatments rather than active self management will help.

The assessment of “red flags” will identify the small number of patients who need referral for an urgent surgical opinion. Similarly, patients with declared suicidal intent require immediate psychiatric referral. These two groups of patients need to be managed separately.

For the vast majority of patients, however, the identification of contributory psychological and social factors should be seen as an investigation of the normal range of reactions to pain rather than the seeking of psychopathology. Questions in the form of interview prompts have been designed to elicit potential psychosocial barriers to recovery in the “yellow flags” system. They can be used at the time of initial presentation by the general practitioner.

Structured interview prompts

What do you understand is the cause of your back pain?

What are you expecting will help you?

How are others responding to your back pain (employer, coworkers, and family)?

What are you doing to cope with back pain?

Have you had time off work in the past with back pain?

Do you think that you will ever return to work? When?

Establish collaboration

Recent studies of miscommunications between doctors and patients with pain show that adequate assessment and collaborative management cannot be achieved without good communication between doctors and patients: only then will patients fully disclose their concerns.

Guidelines for collaborative management of patients with pain

Listen carefully to the patient

Carefully observe the patient's behaviour

Attend not only to what is said but also how it is said

Attempt to understand how the patient feels

Offer encouragement to disclose fears and feelings

Offer reassurance that you accept the reality of the pain

Correct misunderstandings or miscommunications about the consultation

Offer appropriate challenges to unhelpful thoughts and biases (such as catastrophising)

Understand the patient's general social and economic circumstances

The essence of good communication is to work toward understanding a patient's problem from his or her own perspective. In order to do this, the doctor must first gain the patient's confidence. A patient who has been convinced that the doctor takes the pain seriously will give credence to what the doctor says. Unfortunately, the converse is more common, and patients who feel that a doctor has dismissed or under-rated their pain are unlikely to reveal key information or to adhere to treatment advice.

Enhance accurate beliefs and self management strategies

It is easy to overlook the value of simple measures. Many patients respond positively to clear and simple advice, which enables them to manage and control their own symptoms.

Examples of simple management strategies

| • Explain the difference between “hurt” and “harm” | • Advise that analgesic drugs be taken on a regular rather than a pain contingent basis |

|---|---|

| • Reassure patients about the future and the benign nature of their symptoms | • Set realistic goals such as small increases in activity |

| • Help patients regain control over pain | • Suggest rewards for successful achievement (such as listening to some favourite music) |

| • Get patients to “pace” activities—that is, perform activities in manageable, graded stages | |

Some of these strategies may seem self evident or even trivial, but they are not. Only by building confidence slowly is it possible to prevent the development of invalidity. Occasionally patients will seem to “get stuck” and become demoralised or distressed. Suggesting ways to enhance positive self management can help maintain progress towards a more satisfactory lifestyle.

Ways of enhancing positive self management

Get patients to

Identify when they are thinking in unrealistic, unhelpful ways about their pain (such as “It will keep getting worse”) and to change to making a more balanced positive evaluation

Notice when they are becoming tense or angry and then take steps to interrupt their thoughts and to use relaxation strategies

Change how they respond when the pain gets bad (such as pause and take a break)

Document their progress

Elicit and use the help of others to establish and maintain successful coping strategies

Key strategies for assessing and managing distress and anger associated with pain

Distinguish distress associated with pain and disability from more general distress

Identify iatrogenic misunderstandings

Identify mistaken beliefs and fears

Try to correct misunderstandings

Identify iatrogenic distress and anger

Listen and empathise

Above all, don't get angry yourself

The success of the cognitive and behavioural approach described below has stimulated the development of secondary prevention programmes designed to prevent those with low back pain from becoming chronically incapacitated by it. Intervention programmes based on cognitive behaviour therapy have also been shown to be effective in reducing disability.

Manage distress and anger

If patients show evidence of distress or anger, find out why. Various strategies for dealing with distress and anger have been developed.

Managing disabling chronic back pain

A minority of patients become increasingly incapacitated and require more detailed management of what has become a chronic pain problem. Research has shown that the most important influences on the development of chronicity are psychological rather than biomechanical. The psychological factors are high levels of distress, misunderstandings about pain and its implications, and avoidance of activities associated with a fear of making pain worse.

For patients with established chronic disabling pain specialist referral is required. The treatment of choice is an interdisciplinary pain management programme (IPMP). In these programmes the focus is changed from pain to function, with particular emphasis on perceived obstacles to recovery.

These pain management programmes address the clinical flags. The most commonly used therapeutic approach is a cognitive-behavioural perspective with emphasis on self management. Treatment approaches based on cognitive and behavioural principles have been found to be more effective than traditional biomedical or biomechanically oriented interventions.

Defining characteristics of modern pain management programmes

Focus on function rather than disease

Focus on management rather than cure

Integration of specific therapeutic ingredients

Multidisciplinary management

Emphasis on active rather than passive methods

Emphasis on self care rather than simply receiving treatment

Specific chronic pain syndromes

Many specific and more widespread pain syndromes have been described—such as “chronic pain,” late whiplash syndrome, chronic widespread pain, fibromyalgia, somatoform pain disorder, repetitive strain disorder. It seems unlikely that these are distinct entities, and they are best seen as overlapping descriptive terms that do not have specific aetiological significance. Multidisciplinary treatment that includes psychological, behavioural, and psychiatric assessment and interventions is usually required.

Conclusion

There needs to be a revolution in the day to day management of musculoskeletal pain. Not only do we need to abandon prolonged rest and enforced inactivity as a form of treatment, but we also need to appreciate that addressing patients' beliefs, distress, and coping strategies must be an integral part of management if it is to be effective.

Lessons learnt in the management of chronic low back pain have direct relevance to the early and specialist management of musculoskeletal pain in general.

Evidence based summary

Acute back pain is best treated with minimal rest and rapid return to work and normal activity

Psychological and behavioural responses to pain and social factors are the main determinants of chronic pain disability

Specialist psychological treatments and pain management programmes are effective in treating chronic pain

Burton AK, Waddell G, Tillotson KM, Summerton N. Information and advice to patients with back pain can have a positive effect. A randomised controlled trial of a novel educational booklet in primary care. Spine 1999;24:2484-91

Linton SJ. A Review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine 2000;25:1148-56

Morley SJ, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain 1999;80:1-13

Further reading

Clinical Standards Advisory Group. Clinical Standards Advisory Group report on back pain. London: HMSO, 1994

Kendall NAS, Linton SJ, Main CJ. Guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: risk factors for long term disability and work loss. Wellington, NZ: Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee, 1997

Royal College of General Practitioners. Clinical guidelines for the management of acute low back pain. London: RCGP, 1996

Waddell G, Burton K. Occupational health guidelines for the management of low back pain at work—evidence review. London: Faculty of Occupational Medicine, 2000

Roland M, Waddell G, Klaber-Moffett J, Burton AK, Main CJ. The back book. 2nd ed. Norwich: Stationery Office, 2002

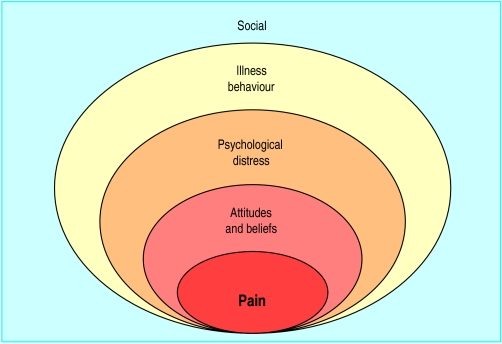

Figure.

Biopsychosocial model of the clinical presentation and assessment of low back pain and disability at a point in time

Figure.

The clinical flags approach to obstacles to recovery from back pain and aspects of assessment

Figure.

Effects of confrontation or avoidance of pain on outcome of episode of low back pain: fear of movement and re-injury can determine how some people recover from back pain while others develop chronic pain and disability

Acknowledgments

The photograph of a man with back pain is reproduced with permission of John Powell/Rex. The figure showing the biopsychosocial model of low back pain is adapted from Waddell G, The back pain revolution, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1998. The figure showing the clinical flags approach to assessing back pain and the box of defining characteristics of modern pain management programmes are adapted from Main CJ and Spanswick CC, Pain management: an interdisciplinary approach, Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 2000. The boxes of guidelines for collaborative management of patients with pain, of key strategies for managing distress and anger associated with pain, of structured interview prompts, and of ways to enhance positive self management are adapted from Main CJ and Watson PJ, in Gifford L, ed, Topical issues in pain, vol 3, Falmouth: CNS Press (in press). The figure showing effects of confrontation or avoidance of pain on outcome of episode of low back pain is adapted from Vlaeyen JWS et al, J Occup Rehabil 1995;5:235-52.

Footnotes

Chris J Main is head of the department of behavioural medicine, Hope Hospital, Salford. Amanda C de C Williams is senior lecturer in clinical health psychology, Guy's, King's, and St Thomas's School of Medicine, University of London.

The ABC of psychological medicine is edited by Richard Mayou, professor of psychiatry, University of Oxford; Michael Sharpe, reader in psychological medicine, University of Edinburgh; and Alan Carson, consultant neuropsychiatrist, NHS Lothian, and honorary senior lecturer, University of Edinburgh. The series will be published as a book in winter 2002.