The British government has launched local and national initiatives to tackle the problems of recruiting and retaining nursing staff. But will these be sufficient to resolve the current crisis?

Difficulties in recruiting and retaining key workers are severely hampering the quality of service the NHS can provide and the progress towards “modernisation.” In our other article published in this same issue, we outline the extent of recruitment and retention problems in the nursing and midwifery workforce. Here, we describe the main initiatives for England introduced by the government to tackle the problems and the new administrative machinery to implement them. We discuss whether these initiatives will be adequate.

Summary points

Problems in recruiting and retaining nurses are hampering the “modernisation” of the NHS

Universities are struggling to fill places on nursing diploma and degree courses so are recruiting students from overseas

New NHS workforce development confederations have the potential to resolve recruitment and retention problems but face substantial obstacles

The existing range of national initiatives may not resolve the crisis fast enough

More widespread or radical solutions may need to be considered

Government policies

The underlying causes of recruitment and retention can be grouped under four broad headings: pay and the cost of living; the changing nature of the job; feeling valued; and the availability of other employment opportunities.1 Recent government policies to tackle these problems relate to the first three. We consider the main initiatives outlined in the NHS Plan and the white paper Improving Working Lives.2,3

Pay and cost of living

The government has sought to improve nurses' salaries through a series of annual increases and special allowances. From 1 April 2001, nurses received a basic pay increase of 3.7%. Senior nurses (including charge nurses, ward sisters, and nurse specialists), on whom the government was dependent to implement key aspects of the NHS Plan, received a rise of 5%.

Yet nurses' basic pay remains low, even in relation to that of other public sector workers. A newly qualified nurse, for example, begins work on £15 445 ($23 544; €24 277) (www.doh.gov.uk). By comparison, a qualified teacher begins work on £16 038 or £17 001 depending on level of attainment (www.dfes.gov.uk), and an untrained police officer on £17 133 (www.homeoffice.gov.uk).

In 2001, London nurses also received a 3.7% increase in the London allowance and a cost of living supplement worth up to £1000. Nurses working in high cost areas outside London received up to £600 as a cost of living allowance. The NHS Plan2 promised to set up more residential units for nurses—up to 2000 extra in London by 2003—and a central accommodation bureau to match nurses with accommodation. A national housing coordinator was appointed in 2000 to determine the extent of the housing problem for nurses. A new scheme to help nurses and other public sector workers to buy their first home was announced in September 2001.4

But living costs remain a concern, particularly in London. At the end of June 2001, the average house price in Greater London for April to June 2001 was £205 831.5 For the same period, the average price in Kent was £128 001, in the West Midlands £82 480, and in Greater Manchester £69 358. On the basis of a typical mortgage allowance of three and a half times salary, a staff nurse on a salary at the top of grade E (£19 935) (www.doh.gov.uk) could borrow only about £69 772 towards a property. A nurse living in London would therefore have to earn £60 000 to afford the same house as a nurse living in Greater Manchester.

Changing nature of job

Increasing bureaucracy with lack of appropriate support

Nurses have experienced an increase in paperwork in recent years, partly as a result of regular audit and clinical governance activities. Like other professionals working in the NHS, nurses complain they do not have good administrative support and work overtime as a result.6 Efforts by the Regulatory Impact Unit at the Department of Health to limit paperwork for general practitioners have not been replicated for nurses.

Limitations to clinical roles and lack of senior clinical posts

More opportunities to expand nurses' clinical roles are being developed. The NHS Plan proposed to extend nurses' prescribing rights, allow nurses to make and receive referrals, and admit and discharge patients.2 The NHS Plan also championed the need to consider new ways of working. The Changing Workforce Programme was subsequently set up by the Department of Health to assess different ways of doing this.7

Historically, senior clinical roles for nurses have been lacking. In 1999 the government reiterated its commitment to a “modern career framework” for nurses, which incorporated the creation of consultant posts for nurses, midwives, and health visitors.8 The NHS has only 500 nurse consultant posts, however, and a doubling of this figure by 2004, as promised by the NHS, may be insufficient given the overall size of the nursing and midwifery workforce. The NHS Plan also promised to “bring back Matron,” but it is unclear how many of these posts will be available.

Caring for more patients with fewer staff

High levels of vacancies and turnover in nursing staff in trusts mean that existing staff have increased workloads and supervise agency staff who are often unfamiliar with the wards.9 Cutbacks in staff costs are resulting in nurses having to care for more, and more acutely ill, patients with fewer staff.9 Evidence from the United States, Canada, and Germany found that nurses were spending time performing functions not related to their professional skills, such as cleaning rooms or moving food trays. Nurses also reported more pressure to take up management responsibility, taking them away from direct patient care.10

To reduce some of these pressures, the government promised to recruit an extra 20 000 nurses (not including healthcare assistants) to the NHS by 2004.2 These headcount numbers (notably not whole time equivalents, which lowers the potential contribution to the NHS) were to be met through attracting back nurses who had left the NHS (“returners”), recruiting trained nurses from overseas, and increasing the number of training places in nursing and midwifery. Two high profile recruitment drives—in 1999 and 2000—yielded 6000 and 5797 returners respectively by September 2000,11 although areas with the highest vacancy rates, such as London, received a disproportionately low share of these nurses.12 A third high profile campaign, in 2001, recruited 713 returners between April and July 2001.13

The Royal College of Nursing suggests, however, that the current number of vacancies for nurses is around 22 000 whole time equivalents. The college calculates that if retirement levels and other losses remain the same, the NHS will need to recruit 110 000 nurses by 2004—less than half of which will be met through training.12

In the NHS Plan, the government pledged year-on-year increases in training places for nurses, midwives, and health visitors so that by 2004 the number of places would be increasing by 5500 a year. However, many universities are struggling to fill places on nursing diploma and degree courses and are recruiting students from overseas to plug the gaps. At South Bank University in London, for example, 30% of current nursing students are not European nationals.14 There is a discrepancy, however, between these and the official figures from the Higher Education Statistics Authority, which suggest overseas students at South Bank University comprise only 7.6%. The reason for this discrepancy could be the way in which data on students' domicile are compiled. None the less, if this example is true of other universities, it may indicate that the NHS is funding a substantial number of places for overseas students who may be less likely to work in the NHS after qualifying.

Feeling valued

Many of the new initiatives outlined above, such as recognising the importance of ongoing staff development, may help to make nurses feel more valued in their work. So too may the efforts to encourage flexible and family friendly work arrangements, outlined in a 1998 government white paper15 and reiterated in the NHS Plan.2 The table shows examples of some of the challenging targets that NHS trusts have been asked to meet. NHS trusts will be held to account for progress against these performance indicators, and the level of progress will be linked to their financial resources.

Racism and violence in the workplace also undermine esteem.9 The government has adopted a zero tolerance policy on violence against staff and is committed to eradicating harassment and discrimination in the NHS. Both of these issues are included in the Department of Health's Improving Working Lives Standard, which NHS employers are expected to meet by April 2003.16

But politicians are sending out mixed messages. On one hand they champion nurses—for example, by setting up the health and social care awards in 1998 to recognise the achievements of staff. On the other hand, the government rhetoric on public service workers can be negative. These mixed messages could undermine hard pressed workers further.

New administrative machinery

To help translate national policies on workforce into action on the ground and encourage delivery, the government has tried to strengthen the administrative machinery.

Nationally

After the launch of the NHS Plan, a series of taskforces were set up to help implement its proposals in key priority areas, such as the workforce and clinical priorities (for example, cancer and coronary heart disease). The national Workforce Taskforce, together with local modernisation boards (responsible for implementing the NHS Plan locally), are charged with encouraging and assessing local progress against targets. Both the Workforce Taskforce and the local modernisation boards are ultimately accountable to the NHS Modernisation Board, which is responsible for overseeing the NHS Plan's implementation nationally. The taskforces have no set life span.

Locally

The government also announced proposals in the NHS Plan to replace the education and training consortiums with new NHS workforce and development confederations. The 39 consortiums were established in England in 1996 and charged with determining the number of non-medical (such as nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy) training places required, commissioning those places, and monitoring the resulting contracts with, for example, education providers.17 The 24 new confederations were set up on 1 April 2001. Their role is similar to the consortiums', except their scope is larger, most notably managing and commissioning education and training for all health professionals in their patch. Initially, the postgraduate deaneries will retain responsibility for funds for medical education and training, but the confederations are intended to absorb this role in future.

Whereas the consortiums comprised a group of representatives from different stakeholders who came together for specific meetings, the new confederations have a more formal corporate structure. Each has a full time chief executive and a chair, and an initial annual budget of about £150m. The confederations are not independent statutory bodies but, unlike the consortiums, have clear lines of accountability to the regional director of workforce development.18

Local stakeholders are represented on confederation boards. Stakeholders include representatives from health authorities, NHS trusts, and primary care trusts; postgraduate deans; and representatives from primary care education, higher education institutions, medical schools, local authorities (social services), the voluntary and independent sectors, and the prison service. Through working with these bodies, and holding the budget for training, the confederations should be able to influence NHS employers in their patch on matters such as recruitment and retention, accommodation for staff, continuing professional development, flexible working opportunities, and leadership programmes.

With a strengthened corporate structure, clearer lines of accountability, explicit targets to meet, a wider reach across the workforce, and a larger budget, the confederations have the potential to make more progress in tackling recruitment and retention problems than their predecessors. But they will also need to overcome considerable obstacles. These include a lack of adequate data on workforce on which to plan; the robustness of trusts' workforce predictions and how these link to the delivery of health improvement programmes; a historical lack of engagement of chief executives in workforce development; and, more fundamentally, the fact that NHS workforce issues are still not high enough on the agendas of many NHS employers.

Conclusion

The government has acknowledged and sought to tackle the serious problems of recruiting and retaining nurses. But despite the resulting national initiatives, problems persist. Overall progress has been slow; staff are unaware of the new opportunities available to them6; some targets are modest, such as plans for 100 trusts to have onsite nurseries by 2004; little effort has been made to evaluate the impact of these initiatives. Workforce issues are still nowhere near the top of the agenda for managers or trust boards, who have other managerial “must do's,” such as reducing waiting lists and times, managing emergency admissions, and breaking even financially. The new confederations have great potential to shape the agenda, but they are still in their infancy.

Will the national initiatives, if fully implemented on time, actually deliver? They will help, but it is questionable whether they will turn the tide. In the meantime more radical suggestions for a complete redesign of the healthcare workforce are being proposed, both as a way of designing a more patient focused health system and as an alternative strategy to tackle problems of recruitment and retention. The merits of these proposals should be openly debated and their evidence base evaluated.

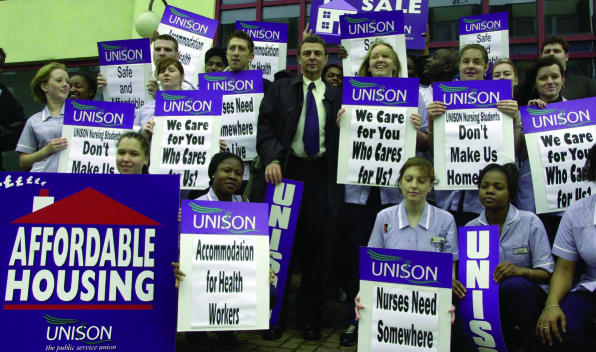

Figure.

JOHN STILWELL/PA

Can the government resolve the housing problems for nurses?

Table.

Targets in staffing and training for NHS employers. Data from Department of Health2 16

| Target

|

Date to be reached

|

|---|---|

| Training and development plans for most health professionals | April 2000 |

| Annual workforce plan | April 2000 |

| Occupational health services and counselling available for all staff | April 2000 |

| Commitment to flexible working arrangements* | April 2003 |

| Childcare coordinator to liaise with staff and childcare providers | 2003 |

For example, flexible working hours.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Dewar and Pippa Gough for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Finlayson B, Dixon J, Meadows S, Blair G. Mind the gap: the extent of the NHS nursing shortage. BMJ. 2002;325:538–541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7363.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. Norwich: Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. Improving working lives in the NHS. London: DoH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department for Transport, Local Government, and the Regions. Nurses, teachers and police get government help to buy homes in housing hotspots. Press release, 6 September 2001.

- 5.Collis P. HM land registry residential property price report: April to June 2001 compared with the same period in 2000. London: Land Registry; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith G, Seccombe I. Changing times: a survey of registered nurses in 1998. Brighton: Institute for Employment Studies; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Changing Workforce Programme. Briefing paper. London: Department of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health. Making a difference: strengthening the nursing, midwifery and health visiting contribution to health and healthcare. London: DoH; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meadows S, Levenson R, Baeza J. The last straw: explaining the NHS nursing shortage. London: King's Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D, Sochalski J, Busse R, Clarke H, et al. Nurses' reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Affairs. 2001;20:43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NHS Executive. Recruiting and retaining nurses, midwives and health visitors in the NHS—a progress report. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royal College of Nursing. Making up the difference: A review of the UK nursing labour market in 2000. London: RCN; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health. Milburn: we are delivering on pledge to bring in more nurses. Press release, 13 July 2001.

- 14.Duffin C. Universities fear drop in foreign student numbers. Nursing Standard. 2001;15:4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health. Working together: securing a quality workforce for the NHS. London: DoH; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health. Improving working lives standard: NHS employers committed to improving the working lives of people who work in the NHS. London: DoH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchan J, Seccombe I, Smith G. Nurses work: an analysis of the UK Nursing Labour Market. Aldershot: Ashgate; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. Workforce Development Confederations guidance: functions of a mature confederation. London: DoH; 2001. [Google Scholar]