Abstract

Introduction

Commercial payer-negotiated rates for cleft lip and palate surgery have not been evaluated on a national scale. The aim of this study was to characterize commercial rates for cleft care, both in terms of nationwide variation and in relation to Medicaid rates.

Methods

A cross-sectional analysis was performed of 2021 hospital pricing data from Turquoise Health, a data service platform that aggregates hospital price disclosures. The data were queried by CPT code to identify 20 cleft surgical services. Within- and across-hospital ratios were calculated per CPT code to quantify commercial rate variation. Generalized linear models were utilized to assess the relationship between median commercial rate and facility-level variables, and between commercial and Medicaid rates.

Results

There were 80,710 unique commercial rates from 792 hospitals. Within-hospital ratios for commercial rates ranged from 2.0–2.9, while across-hospital ratios ranged from 5.4–13.7. Median commercial rates per facility were higher than Medicaid rates for primary cleft lip and palate repair ($5,492.2 vs. $1,739.0), secondary cleft lip and palate repair ($5,429.1 vs. $1,917.0), and cleft rhinoplasty ($6,001.0 vs. $1,917.0) (p<0.001). Lower commercial rates were associated with hospitals that were smaller (p<0.001), safety-net (p<0.001), and non-profit (p<0.001). Medicaid rate was positively associated with commercial rate (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Commercial rates for cleft surgical care demonstrated marked variation within and across hospitals, and were lower for small, safety-net, and/or non-profit hospitals. Lower Medicaid rates were not associated with higher commercial rates, suggesting that hospitals did not utilize cost-shifting to compensate for budget shortfalls resulting from poor Medicaid reimbursement.

Introduction

The economics of payment for cleft lip and palate surgical services have substantial implications for access to and quality of cleft care, yet have remained poorly understood due to absent commercial price transparency. Children with a cleft lip and/or palate may be insured through commercial employer- or group-based health insurance plans, military health insurance (Tricare), Medicaid, or programs such as the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) for children who are not commercially-insured but have family incomes above the Medicaid threshold.1,2 Commercial insurers and Medicaid are the most common payers, with SCHIP reimbursement often similar to Medicaid.3,4 While Medicaid rates are set by states and publicly-accessible,5 commercial payer-negotiated rates have historically been classified beyond the institutional level. Prior nationwide studies have examined commercial charges for cleft procedures,6–10 though charges reflect the amount billed and are not accurate estimates of actual reimbursements.11,12 Single-institution studies privy to commercial payer-negotiated institutional rates show that Medicaid reimburses less than commercial payers,3,13 though the scope and generalizability of these studies are limited.

Understanding the effect of payer status and associated reimbursements has been identified as a priority in cleft care, as it has important implications for both patients and health care systems.14 Variation in commercial rates may highlight disparities in the financial burden borne by patients’ families, as higher rates are passed down in the form of higher premiums, copayments, and deductibles.15–17 In addition, the United States healthcare system operates under the premise that cost-shifting among a diverse payer mix will facilitate a balanced budget, such that higher commercial reimbursements will buffer negative margins from poor Medicaid reimbursement.3 While there is preexisting evidence that Medicaid rates are indeed low compared to commercial rates,3,13 a compensatory increase in commercial rates has not been demonstrated for cleft care.

Recent commercial price transparency reforms have enabled an accurate examination of commercial rates for cleft surgical services. Effective January 1, 2021, all United States hospitals are required to disclose payer-specific negotiated rates for items and services, per Department of Health and Human Services Final Rule.18 The aim of this study was to leverage data made public by this rule to characterize commercial payer-negotiated rates for cleft surgical services in actual dollar amounts, both in terms of variation within and across hospitals, and in relation to Medicaid rates. Given the known heterogeneity in the United States healthcare system, we hypothesized that there would be considerable variation in commercial rates. Further, we hypothesized that commercial rates would be inversely proportional to Medicaid rates (i.e. cost-shifting).

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of 2021 hospital pricing data obtained from Turquoise Health, a data service platform that utilizes machine-learning to aggregate price disclosures from hospital data repositories. As of September 2021, the Turquoise Health platform contained payer-specific private and public pricing data from 5,700 US hospitals (94% of 6,090 total US hospitals).19 Prior published investigations have utilized and validated Turquoise data.19–24 Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used to identify and extract rate information for 20 cleft procedures, grouped into three categories: primary cleft lip and palate repair (CPTs 40700, 40701, 40702, 42200, 42205, 42210, 42235); secondary cleft lip and palate repair, including speech surgery (CPTs 40720, 40761, 30580, 30600, 42260, 42145, 42215, 42220, 42225, 42226, 422227); and cleft rhinoplasty (CPTs 30460, 30462). See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for a list and full descriptions of CPT codes used in the study to identify target cleft lip and palate procedures within Turquoise Health data, http://links.lww.com/PRS/G62.

For the purpose of comparison, Turquoise Health data were additionally queried for commercial rate data for five common plastic surgery procedures: reduction mammaplasty (CPT 19318); breast reconstruction, immediate or delayed, with tissue expander, including subsequent expansion (CPT 19357); revision of reconstructed breast (CPT 19380); mammaplasty, augmentation, with prosthetic implant (CPT 19325); and delayed insertion of breast prosthesis following mastopexy, mastectomy or in reconstruction (CPT 19342). These were chosen based on Blau et al.’s identification of these procedures as the five most common plastic surgery procedures performed within the all-payer American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database from 2005 to 2013,25 which also had Turquoise Health commercial data from greater than 10 hospitals.

Hospital pricing data was merged at facility (i.e. hospital or hospital system) level with data from the 2021 Lown Institute Hospitals Index, a publicly-available dataset containing facility-level data for more 3,709 US hospitals.26,27 Variables within the Index include: hospital size [extra-small (6–49 beds), small (50–99 beds), medium (100–199 beds), large (200–399 beds), and extra-large (400+ beds)], safety-net status (i.e. the 20% of hospitals with the highest proportion of patients eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid), profit status (for-profit vs. non-profit), teaching status (teaching vs. non-teaching), and local population density (urban vs. rural). See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows a flowchart diagraming construction of the study dataset that merges data from Turquoise Health and the 2021 Lown Institute Hospitals Index, http://links.lww.com/PRS/G63.

Statistical Analysis

Ratios of commercial payer-negotiated rates within and across hospitals for each queried CPT code were computed to assess intra- and inter-facility variation, respectively, based on established methodology.28–30 Within-hospital ratios were calculated as the median of the maximum divided by the minimum commercial rate per CPT code for each hospital. Across-hospital ratios were calculated as the 90th percentile median Medicare-normalized rate divided by the 10th percentile median Medicare-normalized rate per CPT code across all hospitals. Medicare-normalized rates (i.e. commercial rate divided by Medicare rate) were utilized for geographic standardization purposes only since, unlike commercial rates, Medicare rates are geographically-price adjusted based on regional differences in input prices.31

Hypothesis testing and multivariable modeling were performed for nonparametric data based on the result of a Shapiro-Wilk test. Commercial rates among cleft surgical groups, and in comparison to Medicaid rates, were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis rank tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, respectively. A generalized linear model with a gamma family and log link modeled associations of median commercial rate per facility with facility-level variables: size, safety-net status, profit status, teaching status, local population density, and location (based on US census region and division).32 A mixed effects generalized linear model with a gamma family and log link, and random intercept by facility, was used to model the relationship between commercial and Medicaid rates. The likelihood ratio (LR) test was used to compare model fitness of the mixed effects generalized linear model to a simple generalized linear regression model. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) informed model selection. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE version 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Geographic mapping of commercial rates was performed using Tableau version 2021.4.4 (Tableau Software LLC, Seattle, WA).

Results

A total of 792 unique hospitals had at least one commercial rate (N=633, 79.9%), Medicare rate (N=327, 41.3%), and/or Medicaid rate (N=321, 40.5%) for the queried CPT codes. There were 559 hospitals with facility-level data, which included 109 (19.5%) safety-net, 498 (89.1%) non-profit, and 282 (50.6%) non-teaching hospitals. Most hospitals were of extra-large (26.5%), large (24.7%), or medium (22.0%) size. A minority of hospitals (N=129, 23.1%) were in rural locations, with an overall geographic distribution by US region of 18.3% Northeast, 29.5% Midwest, 36.5% South, and 15.7% West. There were 80,710 commercial rates that were unique in terms of CPT code, hospital, payer, and plan; of these, 65,946 could be normalized based on the availability of corresponding Medicare rates.

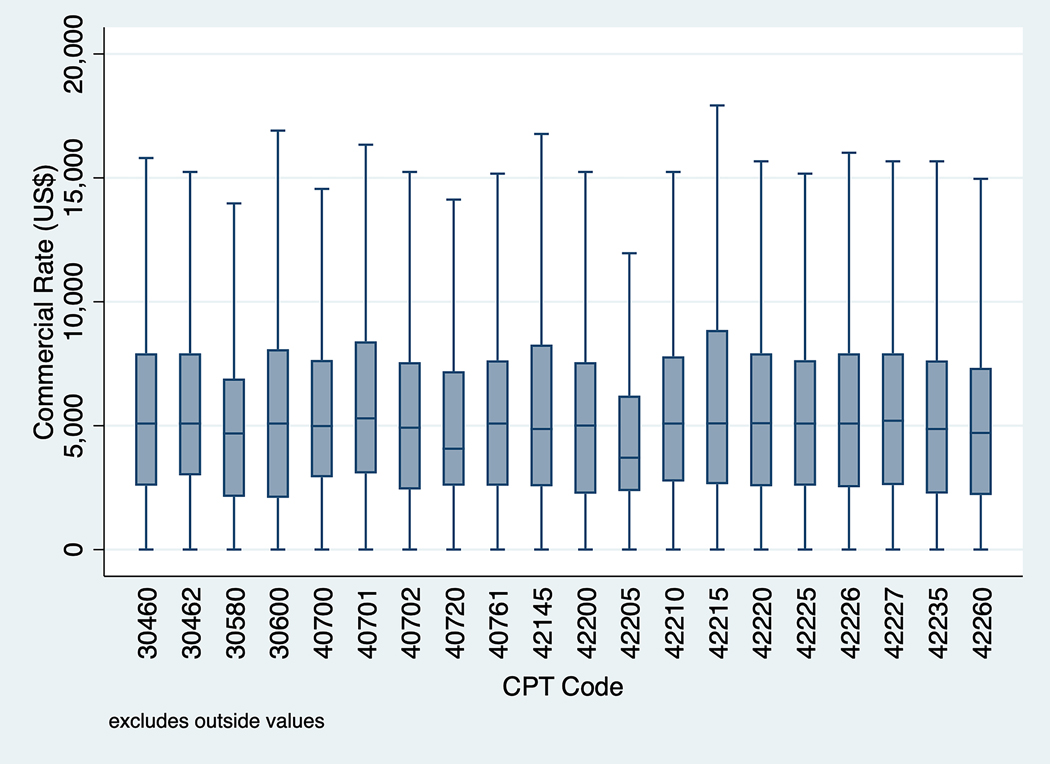

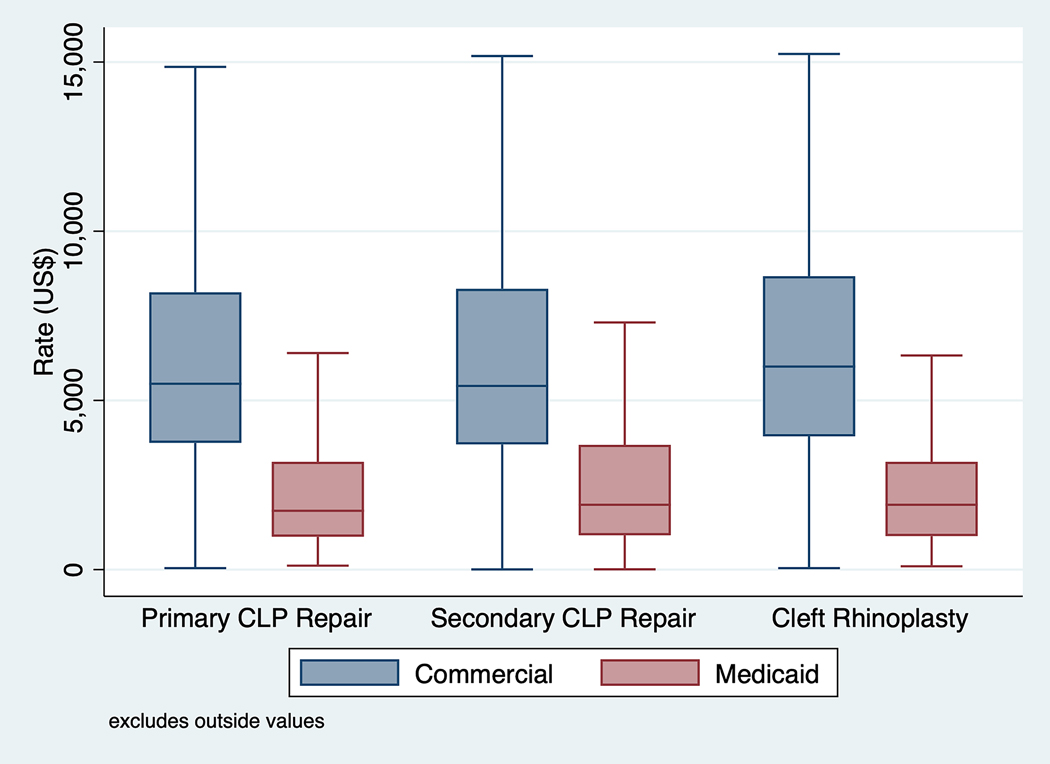

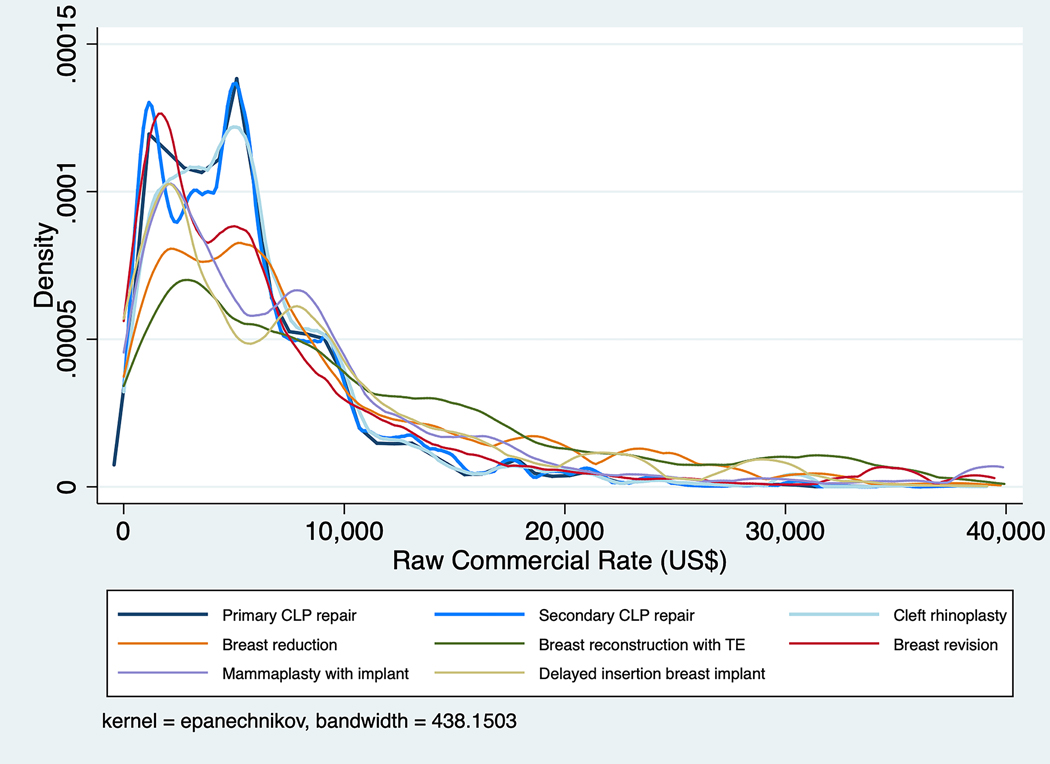

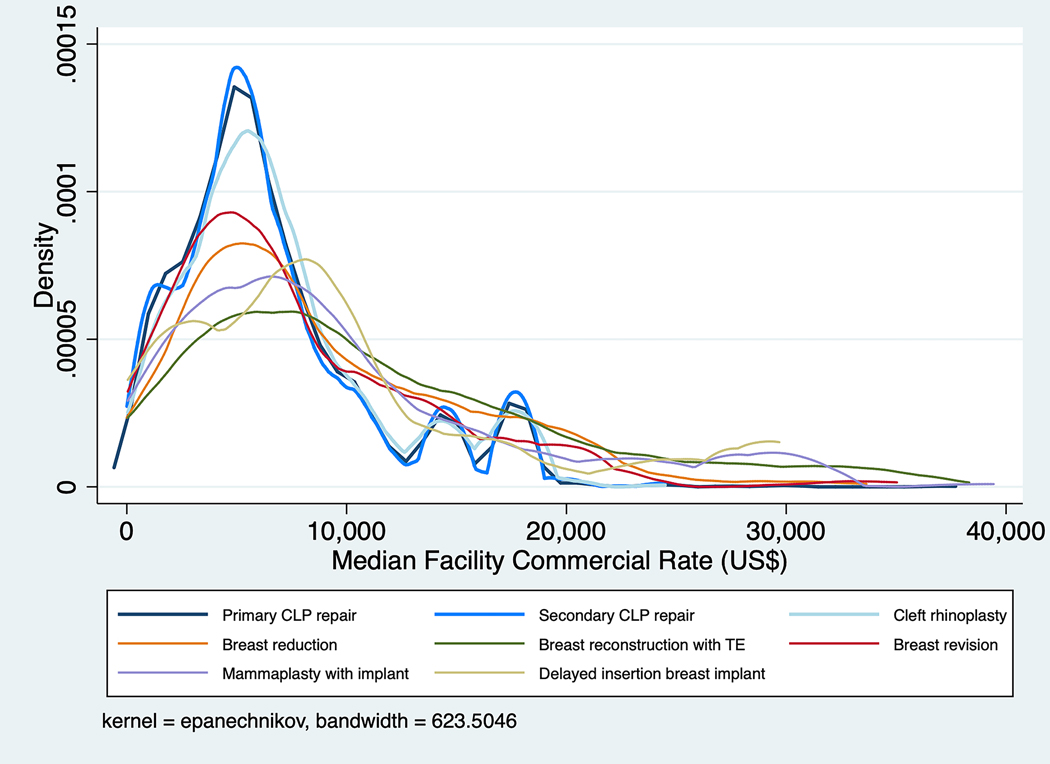

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of raw commercial payer-negotiated rates per CPT code. Within- and across-hospital variation per CPT code is quantified in Table 1. Within-hospital ratios ranged from 2.0 to 2.9, while across-hospital ratios ranged from 5.4 to 13.7. Out of 80,710 total commercial rates, there were 25,042 (31.0%) commercial rates for primary cleft lip and palate repair procedures; 47,949 (59.4%) for secondary cleft lip and palate repair procedures, including speech surgery; and 7,719 (9.6%) for cleft rhinoplasty. As illustrated in Figure 2, raw commercial rates did not differ significantly among primary cleft lip and palate (median $5,492.2, IQR $3,747.3–$8,194.1), secondary cleft lip and palate (median $5,429.1, IQR $3,701.1–$8,298.0), and cleft rhinoplasty (median $6,001.0, IQR $3,939.0–$8,672.0) groups (p=0.063). Median commercial rates per facility were significantly higher than Medicaid rates for all groups (p<0.001). Kernel density distributions of raw commercial rate (Figure 3a) and median facility commercial rate (Figure 3b) in comparison to respective commercial rates for five common plastic surgery procedures demonstrated a greater concentration of lower commercial rates for cleft procedures compared to the comparison common breast procedures.

Figure 1. Commercial rates for cleft surgical services by CPT code.

Variation in commercial rate per CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) code for 80,710 individual hospital-specific commercial plans. See Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1 for descriptions of CPT codes.

Table 1.

Within- and across-hospital variation in commercial payer-negotiated rates for cleft lip and palate repair

| Payer-negotiated rate, $b |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service (CPT code)a | No. rates | No. hospitals | Median (IQR) | p10 | p90 | Within-hospital ratioc | Across-hospital ratiod |

|

| |||||||

| Primary cleft lip and palate repair | |||||||

| Primary UCL/nose repair (40700) | 3,621 | 358 | 5,092.3 (3,724.0–7,084.0) | 1,471.1 | 9,121.0 | 2.2 (1.0 – 6.6) | 8.5 |

| Primary BCL/nose repair, 1-stage (40701) | 3,707 | 354 | 5,315.2 (3,074.4–7,490.0) | 1,689.3 | 9,446.0 | 2.0 (1.0 – 6.2) | 7.7 |

| Primary BCL/nose repair, 2-stage (40702) | 2,751 | 308 | 4,950.5 (3,208.0–6,926.0) | 1,264.5 | 9,121.0 | 2.5 (1.0 – 6.6) | 9.9 |

| CP repair, soft and/or hard palate (42200) | 3,272 | 348 | 4,866.2 (3,118.5–6,860.0) | 1,321.2 | 9,821.0 | 2.0 (1.0 – 5.6) | 9.0 |

| CP and alveolus repair (42205) | 3,606 | 348 | 4,002.1 (2,736.0–5,762.0) | 1,566.3 | 8,034.5 | 2.4 (1.0 – 5.3) | 5.7 |

| CP and alveolus repair, with bone graft (42210) | 4,109 | 378 | 5,202.0 (3,634.0–7,084.0) | 1,590.3 | 9,259.0 | 2.1 (1.0 – 6.1) | 8.1 |

| Repair anterior palate (42235) | 3,811 | 345 | 4,783.5 (2,783.0–6,860.0) | 1,121.4 | 9,235.0 | 2.6 (1.0 – 6.4) | 11.3 |

| Secondary cleft lip and palate repair | |||||||

| Secondary CL repair (40720) | 4,595 | 378 | 3,804.0 (2,859.7–5,900.0) | 1,806.3 | 9,703.4 | 2.5 (1.0 – 5.1) | 5.4 |

| Secondary CL repair with cross lip flap (40761) | 3,731 | 335 | 5,152.0 (3,833.6–6,400.0) | 1,649.7 | 8,607.5 | 2.7 (1.0 – 6.8) | 7.6 |

| Repair oromaxillary fistula (30580) | 5,252 | 420 | 5,004.4 (3,360.8–6,625.5) | 1,054.7 | 9,626.2 | 2.7 (1.0 – 6.2) | 10.8 |

| Repair oronasal fistula (30600) | 5,014 | 389 | 5,151.0 (3,482.0–7,604.5) | 855.4 | 9,821.0 | 2.8 (1.0 – 7.0) | 13.7 |

| Repair nasolabial fistula (42260) | 3,639 | 345 | 5,000.4 (2,783.0–6,323.0) | 1,623.9 | 9,228.8 | 2.7 (1.0 – 6.1) | 11.5 |

| Palatopharyngoplasty (42145) | 3,426 | 538 | 5,086.0 (3,365.8–7,552.9) | 1,623.9 | 11,295.1 | 2.9 (1.0 – 5.5) | 9.0 |

| Palatoplasty, major revision (42215) | 3,426 | 336 | 5,202.0 (4,036.0–7,918.0) | 1,135.3 | 9,235.0 | 2.5 (1.0 – 6.6) | 11.2 |

| Palatoplasty, lengthening (42220) | 3,272 | 337 | 5,315.2 (3,701.1–6,860.0) | 918.1 | 13,913.5 | 2.6 (1.0 – 6.6) | 13.1 |

| Palatoplasty, attach pharyngeal flap (42225) | 4,389 | 348 | 5,249.4 (3,861.5–5,993.0) | 1,591.5 | 8,442.0 | 2.6 (1.0 – 6.6) | 9.1 |

| Pharyngeal flap (42226) | 3,299 | 336 | 5,280.5 (3,348.1–6,926.0) | 1,386.0 | 9,259.0 | 2.3 (1.0 – 6.3) | 9.3 |

| Island flap to palate (42227) | 3,192 | 328 | 5,322.1 (3,892.0–7,300.0) | 1,271.7 | 9,943.6 | 2.6 (1.0 – 6.5) | 9.9 |

| Cleft rhinoplasty | |||||||

| Rhinoplasty; tip only (30460) | 3,816 | 372 | 5,252.5 (3,046.0–6,850.0) | 1,233.9 | 9,617.6 | 2.4 (1.0 – 6.1) | 11.6 |

| Rhinoplasty; tip, septum, osteotomies (30462) | 3,903 | 349 | 5,200.2 (3,816.0–7,198.5) | 2,338.2 | 9,173.0 | 2.4 (1.0 – 6.1) | 5.9 |

CPT, Current Procedural Terminology. IQR, interquartile range. (U)CL, (unilateral) cleft lip. (B)CL, (bilateral) cleft lip. CP, cleft palate. p90, 90th percentile median rate. p10, 10th percentile median rate.

Service names are abbreviated. For full service/procedure names, see Supplemental Table 1.

Calculated based on the median payer-negotiated prices at each hospital.

Calculated as the median of the maximum payer-negotiated rate divided by the minimum payer-negotiated rate for each hospital (each hospital may contain multiple contracted commercial insurance rates that vary by insurance plan).

Calculated as 90th percentile median Medicare-normalized rate divided by the 10h percentile median Medicare-normalized across all hospitals.

Figure 2. Distribution of median commercial and Medicaid rates per hospital for grouped cleft surgical services.

Median (IQR) Medicaid rates were $1,739.0 9 ($972.0–$3,186.2) for primary cleft lip and palate repair, $1,917.0 ($1,015.7–$3,687.9) for secondary cleft lip and palate repair, and $1,917.0 ($991.5–$3,186.4) for cleft rhinoplasty. CLP, cleft lip and palate.

Figure 3. Kernel density distributions of commercial rate for cleft surgical services compared to five common plastic surgery procedures.

Comparison of (a) raw commercial rates and (b) median facility commercial rates for cleft procedures (blue) to five common plastic surgery procedures (CPTs 19318, 19357, 19380, 19325, and 19342; see text for CPT code descriptions). CLP, cleft lip and palate. TE, tissue expander.

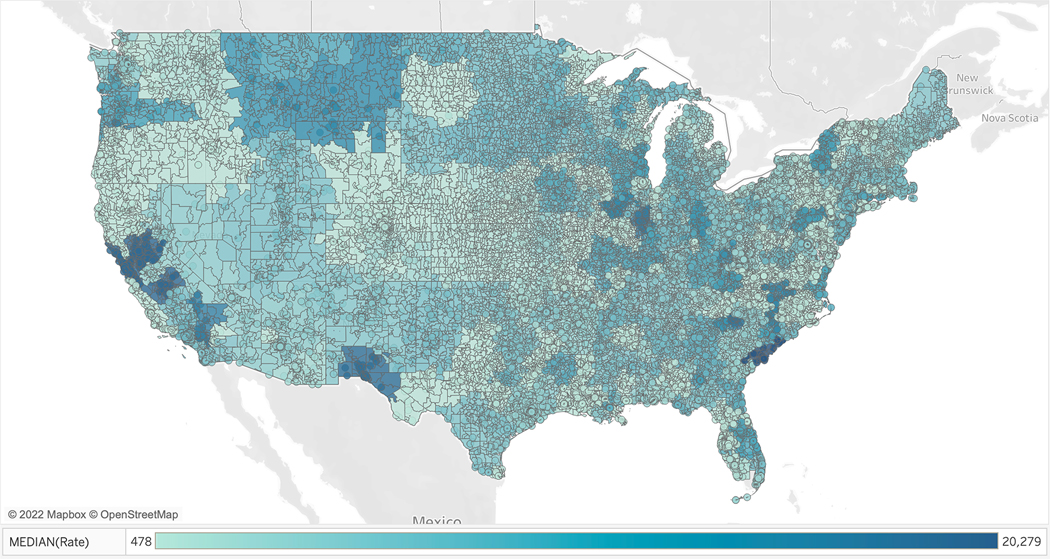

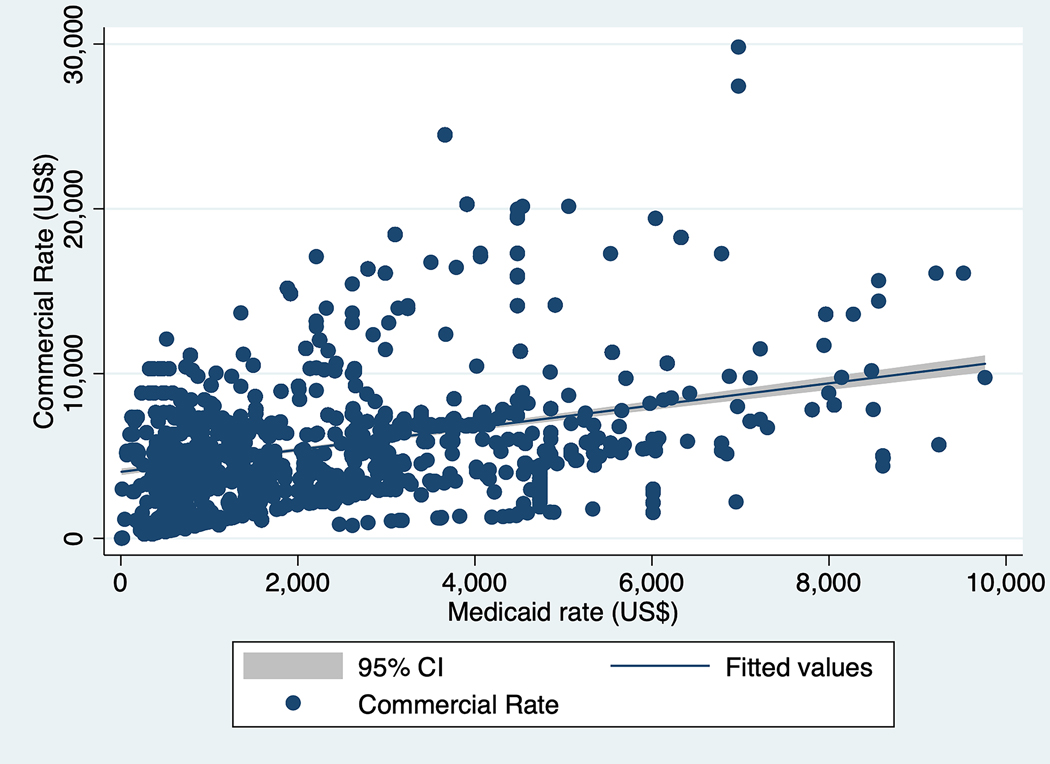

Generalized linear model output for median facility commercial rate as a function of facility-level variables is shown in Table 2. Lower commercial rates were associated with smaller hospital sizes compared to extra-large (400+ bed count) hospitals (p<0.001), safety net status (p<0.001), and non-profit status (p<0.001). Compared to New England, higher commercial rates were observed in the East/West North Central, South Atlantic, East South Central, and Pacific (p<0.03); lower commercial rates were seen in the West South Central (p=0.005). Geographic variation in commercial rate is further illustrated in Figure 4, which shows the median commercial rate by hospital referral region (HRR) for aggregate cleft lip and palate repair procedures. On mixed effect generalized linear regression, Medicaid rate was significantly positively associated with commercial rate (coefficient 0.0000992, 95% CI 0.0000895–0.0001089, p<0.001); for each $100 increase in commercial rate, Medicaid rate increased by approximately 1% (model p-value <0.001, LR test p-value <0.001). The relationship between commercial and Medicaid rates is further demonstrated in Figure 5.

Table 2.

Generalized linear model for median facility commercial rate as a function of facility factors, total cleft services

| Coefficient (β) | Proportional change in rate (eβ) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Hospital size (bed count) | ||||

| Extra-large (400+) | Ref | Ref | - | - |

| Large (200–399) | −0.38 | 0.68 | −0.43 – −0.34 | <0.001 |

| Medium (100–199) | −0.21 | 0.81 | −0.26 – −0.15 | <0.001 |

| Small (50–99) | −0.22 | 0.80 | −0.29 – −0.15 | <0.001 |

| Extra-small (6–49) | −0.32 | 0.73 | −0.39 – −0.25 | <0.001 |

| Safety-net hospital | −0.31 | 0.73 | −0.36 – −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Profit status | ||||

| For-profit | Ref | Ref | - | - |

| Non-profit | −0.13 | 0.88 | −0.18 – −0.07 | <0.001 |

| Academic status | ||||

| Teaching | Ref | Ref | - | - |

| Non-teaching | 0.02 | 1.02 | −0.02 – 0.07 | 0.273 |

| Population density | ||||

| Urban | Ref | Ref | - | - |

| Rural | 0.04 | 1.04 | −0.01 – 0.09 | 0.094 |

| US Census division | ||||

| New England | Ref | Ref | - | - |

| Middle Atlantic | −0.04 | 0.96 | −0.14 – 0.06 | 0.435 |

| East North Central | 0.34 | 1.40 | 0.24 – 0.43 | <0.001 |

| West North Central | 0.31 | 1.36 | 0.20 – 0.42 | <0.001 |

| South Atlantic | 0.18 | 1.20 | 0.07 – 0.28 | 0.001 |

| East South Central | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.02 – 0.23 | 0.024 |

| West South Central | −0.15 | 0.86 | −0.26 – 0.23 | 0.005 |

| Mountain | 0.11 | 1.12 | −0.00 – 0.22 | 0.053 |

| Pacific | 0.50 | 1.65 | 0.39 – 0.62 | <0.001 |

Model uses gamma family and log link. Ref, reference.

Figure 4. Geographic mapping of cleft surgery commercial rates by hospital referral region (HRR).

Aggregate commercial rates (US$) for all cleft procedures are mapped. Alaska and Hawaii are excluded.

Figure 5. Relationship between Medicaid and commercial rates.

Positive slope of fitted values indicates a lack of cost-shifting effect. Medicaid rates of greater than 10,000 are excluded.

Discussion

This study is the first to reveal nationwide commercial payer-negotiated rates for cleft lip and palate reconstructive procedures, demonstrating substantial within- and across-hospital variation. If payer-negotiated rates parallel the out-of-pocket costs paid by commercially-insured cleft patients, these patients both within and across hospitals are likely paying markedly different rates for cleft surgical services depending on their insurance provider and plan. Since the passage of the Hospital Price Transparency Rule, investigators within other medical and surgical fields have pursued similar lines of inquiry, showing large variation in commercial rates within otolaryngology,28,29 radiology,19 ophthalmology,33 and orthopedic surgery.34 Studies have also examined commercial rates for groups of hospital services20,21 and for delivery of such services, such as via telemedicine.30 In their evaluation of commercial rate variation within outpatient otolaryngology procedures, Wang et al.28 define within- and across-hospital ratios in a manner identical to our methodology, thus allowing direct comparison. Wang et al. report a within-hospital ratio range of 2.7 to 5.4, compared to 2.0 to 2.9 in our study, and an across-hospital ratio range of 3.5 to 18.6, compared to 5.4 to 13.7 in our study, indicating comparable within-hospital and greater across-hospital variation for otolaryngology compared to cleft surgical procedures.

More limited across-hospital variation for cleft surgery is additionally evident in the comparison of cleft procedures to five common plastic surgery procedures. As shown in Figure 1, the degree of variation in commercial rate is similar across most cleft CPT codes. These commercial rates are concentrated toward the low end of the reimbursement spectrum, as is evident in the comparison to the common breast procedures in Figure 3. Qualitatively, both raw and median facility commercial prices for breast procedures demonstrate more variation and a wider distribution compared to cleft procedures. While this study is by no means a comprehensive analysis of cleft surgery commercial rates in comparison to other surgical services, the data do reinforce suspicions that cleft surgeries are undervalued in terms of reimbursement and measures of physician productivity.35

Based on generalized linear modeling, hospitals that were smaller, safety-net, and/or non-profit were associated with lower commercial rates compared to counterpart institutions. Significant geographic variation by US census division was also shown in the model, and in Figure 4 by hospital referral region. Commercial rate variation may reflect quality of care, as hospitals that offer new technologies or serve more complex patients may be rewarded with higher rates, or market power, as hospitals may negotiate higher prices based on brand or market concentration.28 It is also possible that price variation has no true etiology, and merely reflects hospitals’ inability to calculate and translate the true cost of care into prices.36 Regardless of the cause, the fact that safety-net hospitals negotiate lower rates threatens to exacerbate health care disparities. Safety-net hospitals provide care to the majority of low-income, underinsured, and uninsured patients in the US.37,38 Further stressing the financial solvency of such institutions may diminish the quality of care that patients with cleft lip and palate receive at these hospitals, which has been shown to be problematic in other areas of plastic surgery.39

Our findings do not support cost-shifting theory that hospitals negotiate higher commercial rates to compensate for poor Medicaid reimbursement. If this were the case, we would have seen a negative association between commercial and Medicaid rates. Instead, our data show a small positive association (p<0.001), suggesting a lack of cost-shifting. Thus, we reject our hypothesis. Prior evidence for cost-shifting in the general healthcare economics literature is limited and stipulates that the effect is dependent on both market competition and payer mix.40–43 For instance, a hospital’s bargaining power is directly proportional to its share of commercially-insured patients.40 Pediatric patients are more commonly publicly-insured compared to adult patients in the United States;4,44 a smaller proportion of privately-insured cleft patients, compared to patients undergoing other surgical procedures nationally, may contribute to the observed lack of cost-shifting. In addition, cleft surgeons operate in a saturated field, with the supply of craniofacial fellowship-trained surgeons exceeding the demand,45 thus potentially diluting bargaining power for cleft surgical rates at the hospital level. It is therefore not surprising that our data did not support cost-shifting theory, however, it is problematic given the lower Medicaid compared to commercial rates demonstrated in our study (p<0.001).

The uncompensated price gap between Medicaid and commercial rates poses several problems in terms of access to cleft surgical services. Medicaid enrollment of the cleft population has increased within the last decade.3 Concurrently, private physicians are increasingly reluctant to accept Medicaid due to poor reimbursement.46 Compared to children with commercial insurance, Medicaid-insured children are less likely to receive specialty care and more likely to encounter difficulty finding an in-network physician.47 Treatment of both Medicaid patients and patients with cleft lip and palate has become increasingly concentrated at academic medical centers and specialty children’s hospitals.7,46 For cleft patients, there are likely multiple etiologies for this trend, including the inability of private physicians and smaller group practices to absorb financial losses from publicly-reimbursed cleft care. In addition, academic and specialty children’s hospitals are more often equipped with multidisciplinary teams needed manage the many dimensions of cleft-related care and medically-complex children; these teams also carry costs related to team certification and maintenance.7,48 If the payer mix shifts more towards Medicaid, the financial sustainability of cleft surgical services may be in jeopardy.

It is unlikely that the public healthcare system will provide a solution to the present dilemma, as federal budget constraints and attempts to reduce national debt make Medicaid rate increases highly improbable. Due to the multidisciplinary nature of cleft care, the bundled payment model theoretically provides a means of incentivizing quality improvement and lower costs; however, significant barriers in the cleft population preclude easy implementation of this model, including the longevity of care,49 and variations in episodes of care, disease severity, and outcomes reporting.50 To maintain access for low-income children to receive cleft care, health systems, and particularly children’s hospitals, must consider alternative means of ensuring fiscal success, such as lowering the cost of care delivery and increasing volume. Alternatively, these facilities will need to procure external funds through local bonds, state subsidies, charitable donations, and foundation endowments.

Limitations of this study include incomplete compliance with the price transparency rule, which limits the comprehensiveness of our data. Gondi et al. found that as of March 2021, 33% of 100 randomly-sampled hospitals reported payer-specific negotiated rates, and 35% of the 100 highest-revenue hospitals posted these rates.51 These disclosure gaps invite potential for selection bias, as disclosing and non-disclosing hospitals may differ in pricing behavior and other hospital characteristics.19,23 Disclosures may increase in the coming years as penalties for nondisclosure become more severe,52 though the 80,710 unique commercial rates from 792 unique hospitals and hospital systems examined in this study provide a robust starting point for this research question in cleft surgery. In addition, our study in unable to evaluate whether commercial plans cover all of the services required by children with cleft lip and palate (e.g. orthodontics, dental care, speech therapy, psychological counseling), which vary based on state mandate and individual plan stipulations,53 or whether commercial price correlates with out-of-pocket costs. Lastly, we cannot evaluate associations between pricing and outcomes, a weakness common to similar studies of commercial pricing.28 Ultimately, we aim to advance value, defined as health outcomes achieved per dollars spent,54,55 within cleft lip and palate surgery. Thus, future studies should more definitively investigate the relationship between commercial rates and outcomes so that prices may be studied in the context of value improvement within the provision of cleft care.

Conclusion

Commercial payer-negotiated rates for cleft surgical care varied within hospitals, across hospitals, and across geographic regions, and were significantly lower for small, safety-net and/or non-profit hospitals. While we have generally known that Medicaid rates are lower than commercial rates, this study highlights the gap between these rates with actual dollar amounts, and shows that hospitals are not making up for low Medicaid rates with higher commercial rates. As demonstrated by the absence of cost-shifting in our study, counting on payer mix that swings towards commercial payers is not a viable solution to longevity in equitable cleft care.

Supplementary Material

List and full descriptions of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes used in study to identify target cleft lip and palate procedures within Turquoise Health data.

Flowchart diagraming construction of study dataset that merges data from Turquoise Health and the 2021 Lown Institute Hospitals Index.

Acknowledgements:

This research was funded in part through the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant P30 CA008748, which supports Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s research infrastructure. In addition, the senior author is funded through a grant from the Center for Translation Science Advancement (CTSA) award number KL2TR003143. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Financial Disclosure Statement:

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript. No payment or compensation was received for this study.

Footnotes

IRB Approval: Individual IRB approval was not required for this study as it does not involve human subjects research.

References

- 1.American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association. Paying for Treatment | ACPA Family Services. Published 2019. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://acpa-cpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Paying-for-Treatment.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Child Health Financing, Racine AD, Long TF, et al. Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): Accomplishments, Challenges, and Policy Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e784–e793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deleyiannis FWB, TeBockhorst S, Castro DA. The Financial Impact of Multidisciplinary Cleft Care: An Analysis of Hospital Revenue to Advance Program Development. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2013;131(3):615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of Children 0–18. KFF. Published October 23, 2020. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/children-0-18/

- 5.Kaura AS, Berlin NL, Momoh AO, Kozlow JH. State Variations in Public Payer Reimbursement for Common Plastic Surgery Procedures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2018;142(6):1653–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allareddy V, Turkistani K, Nanda V, Allareddy V, Gajendrareddy P, Venugopalan SR. Factors Associated With Hospitalization Charges for Cleft Palate Repairs and Revisions. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2012;70(8):1968–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basseri B, Kianmahd BD, Roostaeian J, et al. Current National Incidence, Trends, and Health Care Resource Utilization of Cleft Lip–Cleft Palate. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;127(3):1255–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berk N, Marazita M. Costs of Cleft Lip and Palate: Personal and Societal Implications - Cleft Lip & Palate: From Origin to Treatment, 1st Edition. In: Wyszynski D, ed. Cleft Lip & Palate: From Origin to Treatment. 1st ed. Oxford University Press; 2002. Accessed March 15, 2022. https://doctorlib.info/surgery/treatment/37.html [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen C, Hernandez-Boussard T, Davies SM, Bhattacharya J, Khosla RK, Curtin CM. Cleft Palate Surgery: An Evaluation of Length of Stay, Complications, and Costs by Hospital Type. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2014;51(4):412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boulet SL, Grosse SD, Honein MA, Correa-Villaseñor A. Children with Orofacial Clefts: Health-Care Use and Costs Among a Privately Insured Population. Public Health Reports (1974-). 2009;124(3):447–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rha J, Rathi VK, Naunheim MR, Miller LE, Gadkaree SK, Gray ST. Markup on Services Provided to Medicare Beneficiaries by Otolaryngologists in 2017: Implications for Surprise Billing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(5):662–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dusetzina SB, Basch E, Keating NL. For Uninsured Cancer Patients, Outpatient Charges Can Be Costly, Putting Treatments Out Of Reach. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(4):584–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert MG, Babchenko OOB, Lalikos JF, Rothkopf DM. Inpatient Versus Outpatient Cleft Lip Repair and Alveolar Bone Grafting: A Cost Analysis. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2014;73(Suppl 2):S126–S129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yazdy MM, Honein MA, Rasmussen SA, Frias JL. Priorities for Future Public Health Research in Orofacial Clefts. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2007;44(4):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassell CH, Mendez DD, Strauss RP. Maternal Perspectives: Qualitative Responses about Perceived Barriers to Care among Children with Orofacial Clefts in North Carolina. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2012;49(3):262–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rochlin DH, Ma LW, Sheckter CC, Lorenz HP. Out-of-Pocket Costs and Provider Payments in Cleft Lip and Palate Repair. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 2022;Publish Ahead of Print. Accessed March 13, 2022. https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/SAP.0000000000003081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albino FP, Koltz PF, Girotto JA. Predicting out-of-pocket costs in the surgical management of orofacial clefts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(4):188e–189e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare and Medicaid Programs: CY 2020 Hospital Outpatient PPS Policy Changes and Payment Rates and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System Policy Changes and Payment Rates. Price Transparency Requirements for Hospitals To Make Standard Charges Public. Federal Register. 2019;84(229):65524–65606. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang JX, Makary MA, Bai G. Commercial Negotiated Prices for CMS-specified Shoppable Radiology Services in U.S. Hospitals. Radiology. 2021;000:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang JX, Makary MA, Bai G. Commercial Negotiated Prices for CMS-Specified Shoppable Surgery Services in U.S. Hospitals. Int J Surg. 2021;95:106107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang J(Xuefeng), Makary MA, Bai G. Comparison of US Hospital Cash Prices and Commercial Negotiated Prices for 70 Services. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang J, Makary M, Bai G. Where Are The High-Price Hospitals? With The Transparency Rule In Effect, Colonoscopy Prices Suggest They’re All Over The Place | Health Affairs Forefront. Health Affairs Blog. Published August 11, 2021. Accessed February 12, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210805.748571/full/

- 23.Jiang JX, Polsky D, Littlejohn J, Wang Y, Zare H, Bai G. Factors Associated with Compliance to the Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule: A National Landscape Study. J Gen Intern Med. Published online December 13, 2021:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulaney B, Shah SA, Kim C, Baker LC. Compliance with Price Transparency by California Hospitals. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research; 2021. Accessed February 12, 2022. https://healthpolicy.fsi.stanford.edu/publication/compliance-price-transparency-california-hospitals [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blau JA, Marks CE, Phillips BT, Hollenbeck ST. Disparities between operative time and relative value units for plastic surgery procedures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2021;148(3):638–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lown Institute. Lown Institute Hospital Index. Lown Institute Hospital Index. Published 2022. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://lownhospitalsindex.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saini V, Brownlee S, Gopinath V, Smith P, Chalmers K, Garber J. 2021 Methodology Lown Institute Hospitals Index for Social Responsibility. The Lown Institute; 2021:1–25. https://lownhospitalsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021_Methodology_9-21-21.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang AA, Xiao R, Sethi RKV, Rathi VK, Scangas GA. Private Payer–Negotiated Prices for Outpatient Otolaryngologic Surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Published online September 28, 2021:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao R, Rathi VK, Gross CP, Ross JS, Sethi RKV. Payer-Negotiated Prices in the Diagnosis and Management of Thyroid Cancer in 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(2):184–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu SS, Rathi VK, Ross JS, Sethi RKV, Xiao R. Payer-Negotiated Prices for Telemedicine Services. J Gen Intern Med. Published online January 14, 2022:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MaCurdy T, Shafrin J, DeLeire T, et al. Geographic Adjustment of Medicare Payments to Physicians: Evaluation of IOM Recommendations. Acumen, LLC; 2012:1–132. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/physicianfeesched/downloads/geographic_adjustment_of_medicare_physician_payments_july2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. Published 2010. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkowitz ST, Siktberg J, Hamdan SA, Triana AJ, Patel SN. Health Care Price Transparency in Ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139(11):1210–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Amore T, Goh GS, Courtney PM, Klein GR. Do New Hospital Price Transparency Regulations Reflect Value in Arthroplasty? J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;Publish Ahead of Print. Accessed February 12, 2022. https://journals.lww.com/10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rochlin D, Chaya B, Flores R. National Undervaluation of Cleft Surgical Services: Evidence from a Comparative Analysis of 50,450 Cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cram P, Cram E, Antos J, Sittig DF, Anand A, Li Y. Availability of Prices for Shoppable Services on Hospital Internet Sites. Am J Manag Care. 2021;27(12):e426–e428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chatterjee P, Qi M, Werner RM. Association of Medicaid Expansion With Quality in Safety-Net Hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadley J, Cunningham P. Availability of Safety Net Providers and Access to Care of Uninsured Persons. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(5):1527–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradley CJ, Dahman B, Shickle LM, Lee W. Surgery Wait Times and Specialty Services for Insured and Uninsured Breast Cancer Patients: Does Hospital Safety Net Status Matter? Health Serv Res. 2012;47(2):677–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu VY. Hospital Cost Shifting Revisited: New Evidence from the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. International Journal of Health Care Finance & Economics. 2010;10(1):61–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson J Hospitals Respond To Medicare Payment Shortfalls By Both Shifting Costs And Cutting Them, Based On Market Concentration. Health Affairs. 2011;30(7):1265–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frakt AB. How Much Do Hospitals Cost Shift? A Review of the Evidence. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):90–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chernew ME, He H, Mintz H, Beaulieu N. Public Payment Rates For Hospitals And The Potential For Consolidation-Induced Cost Shifting. Health Affairs. 2021;40(8):1277–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaiser Family Foundation. Health Insurance Coverage of Adults 19–64. KFF. Published October 23, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2022. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/adults-19-64/

- 45.Luby AO, Ranganathan K, Matusko N, Buchman SR. Assessing the key predictors of an academic career after craniofacial surgery fellowship. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2020;146(6):759e–767e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunningham P, May J. Medicaid patients increasingly concentrated among physicians. Track Rep. 2006;16:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skinner AC, Mayer ML. Effects of insurance status on children’s access to specialty care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robin NH, Baty H, Franklin J, et al. The multidisciplinary evaluation and management of cleft lip and palate. South Med J. 2006;99(10):1111–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cassell CH, Meyer R, Daniels J. Health care expenditures among Medicaid enrolled children with and without orofacial clefts in North Carolina, 1995–2002. Birth Defect Res A. 2008;82(11):785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ahsanuddin S, Sayegh F, Lu J, Sanati-Mehrizy P, Taub PJ. Considerations for Payment Bundling in Cleft Care. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2021;147(4):927–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gondi S, Beckman AL, Ofoje AA, Hinkes P, McWilliams JM. Early Hospital Compliance With Federal Requirements for Price Transparency. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(10):1396–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.CY 2022. Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System and Ambulatory Surgical Center Payment System Final Rule (CMS-1753FC) | CMS. Published November 2, 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cy-2022-medicare-hospital-outpatient-prospective-payment-system-and-ambulatory-surgical-center-0

- 53.Wanchek T, Wehby G. State Mandated Coverage of Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate Treatment. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2020;57(6):773–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Porter ME. What Is Value in Health Care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abbott MM, Alkire BC, Meara JG. The Value Proposition: Using a Cost Improvement Map to Improve Value for Patients with Nonsyndromic, Isolated Cleft Palate: Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;127(4):1650–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List and full descriptions of Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes used in study to identify target cleft lip and palate procedures within Turquoise Health data.

Flowchart diagraming construction of study dataset that merges data from Turquoise Health and the 2021 Lown Institute Hospitals Index.