Abstract

PURPOSE

The phase III Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB)/SWOG 80405 trial found no difference in overall survival (OS) in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy in combination with either bevacizumab or cetuximab. We investigated the potential prognostic and predictive value of HER2 amplification and gene expression using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and NanoString data.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Primary tumor DNA from 559 patients was profiled for HER2 amplification by NGS (FoundationOne CDx). Tumor tissue from 925 patients was tested for NanoString gene expression using an 800-gene panel. OS and progression-free survival (PFS) were the time-to-event end points.

RESULTS

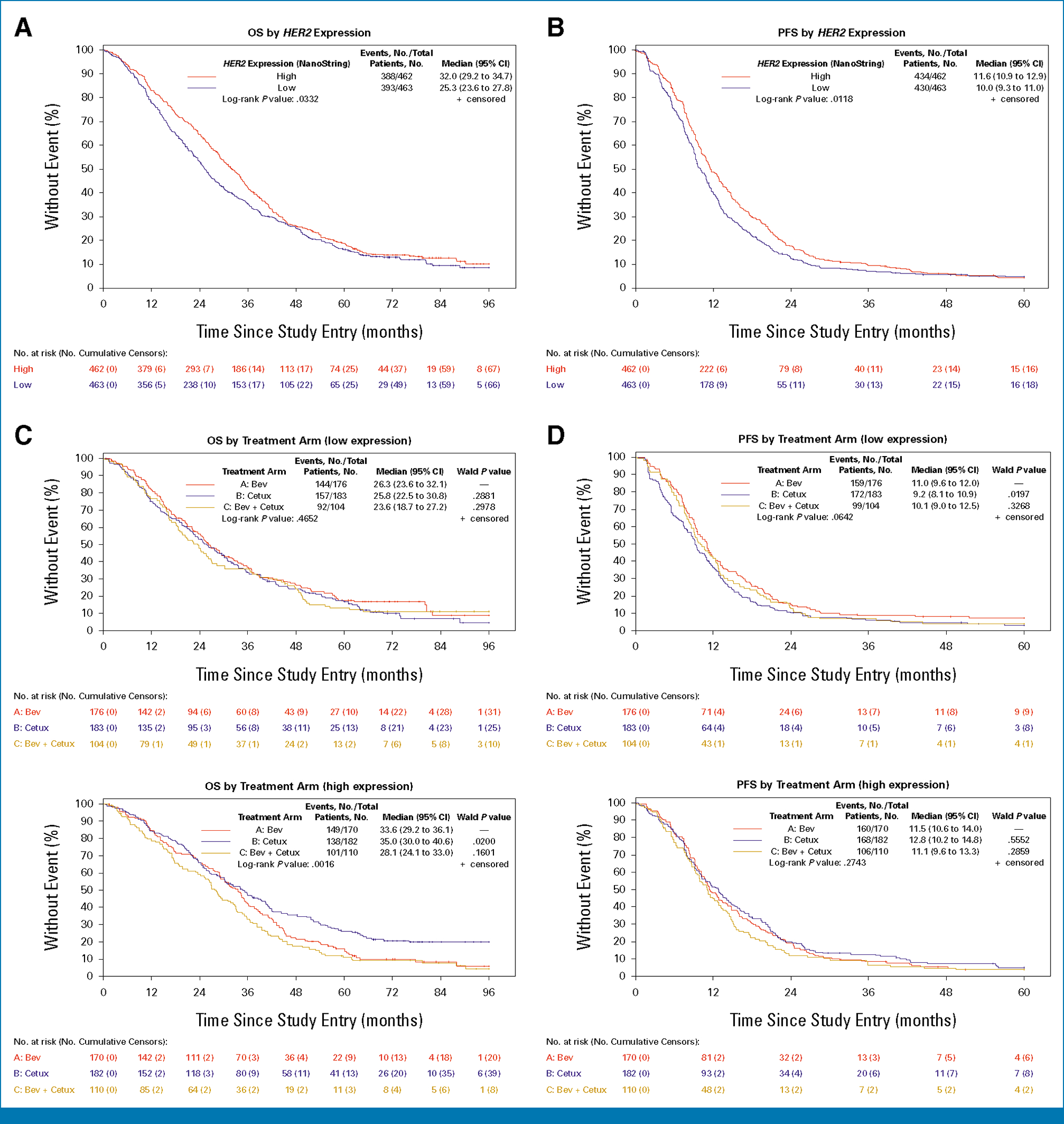

High HER2 expression (dichotomized at median) was associated with longer PFS (11.6 v 10 months, P = .012) and OS (32 v 25.3 months, P = .033), independent of treatment. An OS benefit for cetuximab versus bevacizumab was observed in the high HER2 expression group (P = .02), whereas a worse PFS for cetuximab was seen in the low-expression group (P = .019). When modeled as a continuous variable, increased HER2 expression was associated with longer OS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.83 [95% CI, 0.75 to 0.93]; adjusted P = .0007) and PFS (HR, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.74 to 0.91]; adjusted P = .0002), reaching a plateau effect after the median In patients with HER2 expression lower than median, treatment with cetuximab was associated with worse PFS (HR, 1.38 [95% CI, 1.12 to 1.71]; adjusted P = .0027) and OS (HR, 1.28 [95% CI, 1.02 to 1.59]; adjusted P = .03) compared with that with bevacizumab. A significant interaction between HER2 expression and the treatment arm was observed for OS (Pintx = .017), PFS (Pintx = .048), and objective response rate (Pintx = .001).

CONCLUSION

HER2 gene expression was prognostic and predictive in CALGB/SWOG 80405 HER2 tumor expression may inform treatment selection for patients with low HER2 favoring bevacizumab- versus cetuximab-based therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States.1 The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB)/SWOG 80405 trial was conducted to determine whether the addition of either cetuximab or bevacizumab to standard chemotherapy was superior as first-line treatment in metastatic CRC (mCRC). The primary end point was overall survival (OS). In the primary analysis on 1,137 patients with KRAS wild-type (WT; codons 12/13), no statistically significant difference in OS was found between the bevacizumab and cetuximab arms.2 Since the trial began, our understanding of which patients benefit most from antiepidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR/HER1) therapies has advanced, with evidence now showing that the presence of noncodon 12/13 KRAS mutations confers resistance to EGFR inhibitors.3–5 Extended RAS testing is currently required before treatment with EGFR-targeting agents to screen out patients with RAS-mutated tumors. In addition to RAS mutations, several other mechanisms of primary resistance to EGFR inhibitors have been identified.6–9 Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2/HER2) amplification is detected in 2%–3% of genetically unselected CRC, reaching about 5% in RAS WT mCRC. The value of HER2 as a prognostic biomarker in CRC is still debated, whereas its role as an oncogenic driver and therapeutic target has been established.10–12 HER2 amplification testing is currently recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines at diagnosis of mCRC, alongside KRAS/NRAS and BRAF status, to evaluate eligibility to receive anti-HER2 treatment.13 The recommended methodologies for diagnostic testing are immunohistochemistry (IHC), fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), or next-generation sequencing (NGS). HER2 overexpression by IHC is defined as positive 3+ staining in >50% of tumor cells, whereas cases with a HER2 score of 2+ should be tested with FISH.14,15 HER2 amplification by FISH is considered positive when the HER2:CEP17 ratio is ≥2 in >50% of tumor cells.14,15 HER2 amplification is one of the mechanisms implicated in resistance to anti-EGFR antibodies.16,17 At the moment, however, such evidence is not conclusive and further validation is needed.

In the current scenario where the increased use of NGS technologies offers the opportunity to leverage new profiling data as new predictive and/or prognostic tools,18 understanding the clinical significance and impact of HER2 gene expression as compared with HER2 amplification may provide additional evidence to support the role of HER2 as a biomarker for treatment selection in mCRC. In this study, we aimed to determine the predictive and prognostic value of HER2 gene expression using NanoString data from patients with mCRC enrolled in the CALGB/SWOG 80405 trial.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

CALGB/SWOG 80405

CALGB/SWOG 80405 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00265850) was a randomized phase III trial designed to compare cetuximab, bevacizumab, or cetuximab/bevacizumab each combined with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin or fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan as first-line treatment of mCRC. Within 3 years, emerging evidence on the lack of efficacy of EGFR antibodies in KRAS-mutant tumors and failures of the dual antibody plus chemotherapy combination led to a restriction of eligibility to patients with KRAS WT (codon 12/13) tumors and to the discontinuation of the cetuximab/bevacizumab arm. Eligibility criteria and study details can be found in the original publication.2

OS was defined as the interval between the time of random assignment until death because of any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time of random assignment until first documented progression of disease or death. For patients alive without documented tumor progression, OS and PFS were censored at the last known follow-up and at the most recent disease assessment, respectively. Objective response was defined per RECIST v1.0.19

Gene Expression Analysis by NanoString

The original study protocol included gene expression analyses as a potential predictive and prognostic marker. Custom-designed CRC NanoString code sets were used to measure gene expression using 250 ng of total RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples in a non–CLIA-approved research laboratory as previously described.20 Positive and negative control probes were included for hybridization efficiency and background calculations. Gene expression was quantified using the nCounter Analysis System, and raw counts were generated by using the nSolver 4.0 Software (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA).

NGS of Tumor DNA

Tumor DNA isolated from FFPE samples was profiled by NGS on a 324-gene panel (FoundationOne CDx) at Foundation Medicine (Cambridge, MA) following standard procedures. HER2 amplification was defined as copy number variation ≥6 per Foundation Medicine.

Statistical Analysis

Patient baseline clinical characteristics were compared between HER2 expression groups (high v low by median cutoff). Continuous variables were presented as medians with interquartile percentiles, whereas categorical variables were expressed as count with percentages. Univariate comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square tests for categorical variables.

The distribution of time-to-event end points was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in OS and PFS were tested using the log-rank test. Differences in objective response rate (ORR) were compared using the chi-square test. HER2 expression was dichotomized as low or high using the overall median of all patients in the NanoString data set as the cutoff for the generation of Kaplan-Meier curves. Multivariable Cox models were used to assess the prognostic associations of both HER2 amplification and expression with OS and PFS. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess the prognostic associations with ORR. For modeling purposes, HER2 expression was treated as a continuous variable, scaled (divided by 100) to aid interpretability, and modeled using a linear spline with a knot at the median of all NanoString data. A visual inspection of the association between HER2 expression and OS/PFS using the restricted cubic spline methodology was performed (Data Supplement, Fig S1, online only). A linear spline with one knot at the median was chosen for model fitting. Three models were performed for each analysis: model 1 unadjusted, model 2 adjusted for clinical factors (arm, age, chemotherapy, previous adjuvant therapy, previous radiation therapy, race, sex, number of metastatic sites, performance score, tumor sidedness, and tumor biology), and model 3 additionally adjusted for molecular factors (BRAF, RAS, and microsatellite instability [MSI] status). The predictive effect of each main variable was examined by including amplification/expression, treatment arm, and the interaction between the two in the model while adjusting for the covariates mentioned above. Likelihood ratio test was used for the tests of interactions. The differential treatment effect was estimated at first quartile (Q1), median, and third quartile (Q3) of the HER2 expression level. HER2 expression analyses were performed using the complete NanoString data set. Supplementary analyses were performed on the population of patients with both NGS and NanoString data available. Additional sensitivity analyses were also performed using the complete NanoString data set while (1) subsetting on patients with RAS/BRAF WT and non-MSI high (MSI-H) tumors and (2) subsetting on patients who received either bevacizumab or cetuximab as individual agents in combination with chemotherapy.

P values <.05 were considered as statistically significant, except for the interaction term, where .1 was used.

Ethics Statement

CALGB/SWOG 80405 received approval by the institutional review board of participating centers, and all participating patients provided written informed consent to permit additional studies on their submitted tumor tissue. Patient registration, data collection, and data analysis were performed by the Alliance Statistics and Data Management Center. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines from the Declaration of Helsinki, Belmont Report, and the US Common Rule.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics

Of 1,843 patients who consented to correlative studies within CALGB/SWOG 80405, 559 were profiled for HER2 amplification by NGS and 925 were tested with NanoString gene expression (NanoString cohort). A total of 505 tumors with both NGS and NanoString data available were identified and included in secondary analyses (Data Supplement, Fig S2). Patient and tumor characteristics for the CALGB/SWOG 80405 population are summarized in the Data Supplement (Table S1).

No significant differences were observed between HER2-high versus HER2-low expression groups in terms of age, sex, race/ethnicity, performance status, tumor location, number of metastatic sites, and treatment distribution in the NanoString cohort (Table 1). RAS mutational status and MSI status were balanced between HER2 expression groups, whereas BRAF mutations were more frequent in HER2-low tumors (16.9% v 7.5%, P = .0001). Among the 505 patients with available NGS data within the NanoString cohort, 16 harbored a HER2 amplification (3%), all within microsatellite-stable tumors. WT RAS was more prevalent among HER2-amplified tumors (94% v 69%, P = .036). HER2 amplification was significantly associated with HER2 expression (P < .001, Data Supplement, Fig S3). The baseline characteristics on the basis of tumor HER2 amplification by NGS are reported in the Data Supplement (Table S2). Among patients with NGS data, tumors obtained from 10 patients presented a HER2 somatic mutation, including known HER2-activating mutations, with one patient’s tumor having two concurrent mutations (Data Supplement, Table S3). No cases of concomitant HER2 mutation(s) and amplification were observed. Nine of 10 of these tumors had available NanoString data (Data Supplement, Fig S4).

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Demographics of Patients According to Tumor HER2 Expression (NanoString cohort)

| Patient Characteristic | HER2 Expression (median cutoff) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 462) | Low (n = 463) | Total (n = 925) | P | |

| Age, years | .1363 | |||

| N | 462 | 463 | 925 | |

| Median | 61.2 | 59.4 | 60.4 | |

| Q1, Q3 | 53.0, 68.8 | 50.8, 68.9 | 52.1, 68.8 | |

| Treatment arm, No. (%) | .8720 | |||

| A: Bev | 170 (36.8) | 176 (38.0) | 346 (37.4) | |

| B: Cetux | 182 (39.4) | 183 (39.5) | 365 (39.5) | |

| C: Bev + Cetux | 110 (23.8) | 104 (22.5) | 214 (23.1) | |

| Planned protocol chemotherapy, No. (%) | .8287 | |||

| FOLFOX | 357 (77.3) | 355 (76.7) | 712 (77.0) | |

| FOLFIRI | 105 (22.7) | 108 (23.3) | 213 (23.0) | |

| Previous adjuvant chemotherapy, No. (%) | .8378 | |||

| No | 398 (86.1) | 401 (86.6) | 799 (86.4) | |

| Yes | 64 (13.9) | 62 (13.4) | 126 (13.6) | |

| Previous pelvic radiation therapy, No. (%) | .0548 | |||

| No | 437 (94.6) | 423 (91.4) | 860 (93.0) | |

| Yes | 25 (5.4) | 40 (8.6) | 65 (7.0) | |

| Sex, No. (%) | .6091 | |||

| Male | 283 (61.3) | 276 (59.6) | 559 (60.4) | |

| Female | 179 (38.7) | 187 (40.4) | 366 (39.6) | |

| Race, No. (%) | .6835 | |||

| Missing | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| White | 392 (85.6) | 398 (86.5) | 790 (86.1) | |

| Other | 66 (14.4) | 62 (13.5) | 128 (13.9) | |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | .4362 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 19 (4.1) | 20 (4.3) | 39 (4.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 419 (90.7) | 426 (92.0) | 845 (91.4) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Unknown | 22 (4.8) | 17 (3.7) | 39 (4.2) | |

| Performance score, No. (%) | .9684 | |||

| 0 | 274 (59.3) | 274 (59.2) | 548 (59.2) | |

| 1 | 188 (40.7) | 189 (40.8) | 377 (40.8) | |

| No. of metastatic sites, No. (%) | .4046 | |||

| Missing | 5 | 4 | 9 | |

| 1 | 233 (51.0) | 242 (52.7) | 475 (51.9) | |

| 2 | 151 (33.0) | 158 (34.4) | 309 (33.7) | |

| 3+ | 73 (16.0) | 59 (12.9) | 132 (14.4) | |

| Liver metastases only, No. (%) | .2483 | |||

| Missing | 5 | 4 | 9 | |

| No | 287 (62.8) | 305 (66.4) | 592 (64.6) | |

| Yes | 170 (37.2) | 154 (33.6) | 324 (35.4) | |

| Tumor location (sidedness), No. (%) | .0919 | |||

| Missing | 18 | 23 | 41 | |

| Left | 275 (61.9) | 248 (56.4) | 523 (59.2) | |

| Right/transverse | 169 (38.1) | 192 (43.6) | 361 (40.8) | |

| Synchronous/metachronous, No. (%) | .5408 | |||

| Missing | 14 | 13 | 27 | |

| Synchronous | 352 (78.6) | 361 (80.2) | 713 (79.4) | |

| Metachronous | 96 (21.4) | 89 (19.8) | 185 (20.6) | |

| BRAF mutation, No. (%) | .0001 | |||

| Missing | 102 | 60 | 162 | |

| Wild-type | 333 (92.5) | 335 (83.1) | 668 (87.5) | |

| Mutant | 27 (7.5) | 68 (16.9) | 95 (12.5) | |

| RAS mutation, No. (%) | .7054 | |||

| Missing | 105 | 62 | 167 | |

| Wild-type | 252 (70.6) | 278 (69.3) | 530 (69.9) | |

| Mutant | 105 (29.4) | 123 (30.7) | 228 (30.1) | |

| MSI status from PCR, No. (%) | .9604 | |||

| Missing | 109 | 83 | 192 | |

| MSI-H | 19 (5.4) | 20 (5.3) | 39 (5.3) | |

| MSI-L | 25 (7.1) | 25 (6.6) | 50 (6.8) | |

| MSS | 309 (87.5) | 335 (88.2) | 644 (87.9) | |

| HER2 gene amplification (FM), No. (%) | .0002 | |||

| Not amplified | 227 (93.8) | 262 (99.6) | 489 (96.8) | |

| Amplified | 15 (6.2) | 1 (0.4) | 16 (3.2) | |

NOTE. Comparisons are between the population with HER2 expression high versus low (median cutoff). P values were generated using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests and Pearson chi-square tests for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively.

Abbreviations: Bev, bevacizumab; Cetux, cetuximab; FM, foundation medicine; FOLFOX, infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin; FOLFIRI, fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan; MSI, microsatellite instability; MSS, microsatellite stable; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Q1,first quartile (ie, 25th percentile); Q3, third quartile (ie, 75th percentile).

Prognostic and Predictive Values in OS and PFS of HER2 Expression and HER2 Amplification in CALGB/SWOG 80405

HER2 Expression Dichotomized at the Median

Tumor HER2 expression higher than the median (cutoff value of 467) was significantly associated with longer PFS and OS (11.6 v 10 months, P = .012, and 32 v 25.3 months, P = .033, respectively) in the NanoString cohort (Figs 1A and 1B) and higher ORR (63.6% v 55.3%, P = .010; Table 2). When PFS and OS were evaluated by treatment arm among each HER2 expression level, patients in the high-expression group treated with cetuximab showed longer OS compared with those treated with bevacizumab (35 v 33.6 months, respectively, P = .02), whereas patients in the low-expression group receiving cetuximab had shorter PFS (cetuximab v bevacizumab: 9.2 v 11 months, P = .020; Figs 1C and 1D). No significant differences in ORR were observed across treatment arms in either group (Table 2).

FIG 1.

OS and PFS by HER2 gene expression in CALGB/SWOG 80405 (NanoString cohort). (A) OS and (B) PFS for HER2 high versus low in the entire NanoString cohort (n 5 925). (C) OS and (D) PFS by treatment arm among each HER2 gene expression group. Bev, bevacizumab; CALCB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; Cetux, cetuximab; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

TABLE 2.

ORR by HER2 Gene Expression in CALGB/SWOG 80405 (NanoString Cohort)

| Outcome | ORR × HER2 Expression | ORR × Arm (high HER2 expression) | ORR × Arm (low HER2 expression) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 462), No. (%) | Low (n = 463), No. (%) | Total (n = 925), No. (%) | P | A: Bev (n = 170), No. (%) | B: Cetux (n = 182), No. (%) | C: Bev + Cetux (n = 110), No. (%) | Total (n = 462), No. (%) | P | A: Bev (n = 176), No. (%) | B: Cetux (n = 183), No. (%) | C: Bev + Cetux (n = 104), No. (%) | Total (n = 463), No. (%) | P | |

| Overall response | .010 a | .19a | .69a | |||||||||||

| No | 168 (36.4) | 207 (44.7) | 375 (40.5) | 70 (41.2) | 58 (31.9) | 40 (36.4) | 168 (36.4) | 83 (47.2) | 80 (43.7) | 44 (42.3) | 207 (44.7) | |||

| Yes | 294 (63.6) | 256 (55.3) | 550 (59.5) | 100 (58.8) | 124 (68.1) | 70 (63.6) | 294 (63.6) | 93 (52.8) | 103 (56.3) | 60 (57.7) | 256 (55.3) | |||

Abbreviations: Bev, bevacizumab; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; Cetux, cetuximab; ORR, objective response rate.

Chi-square.

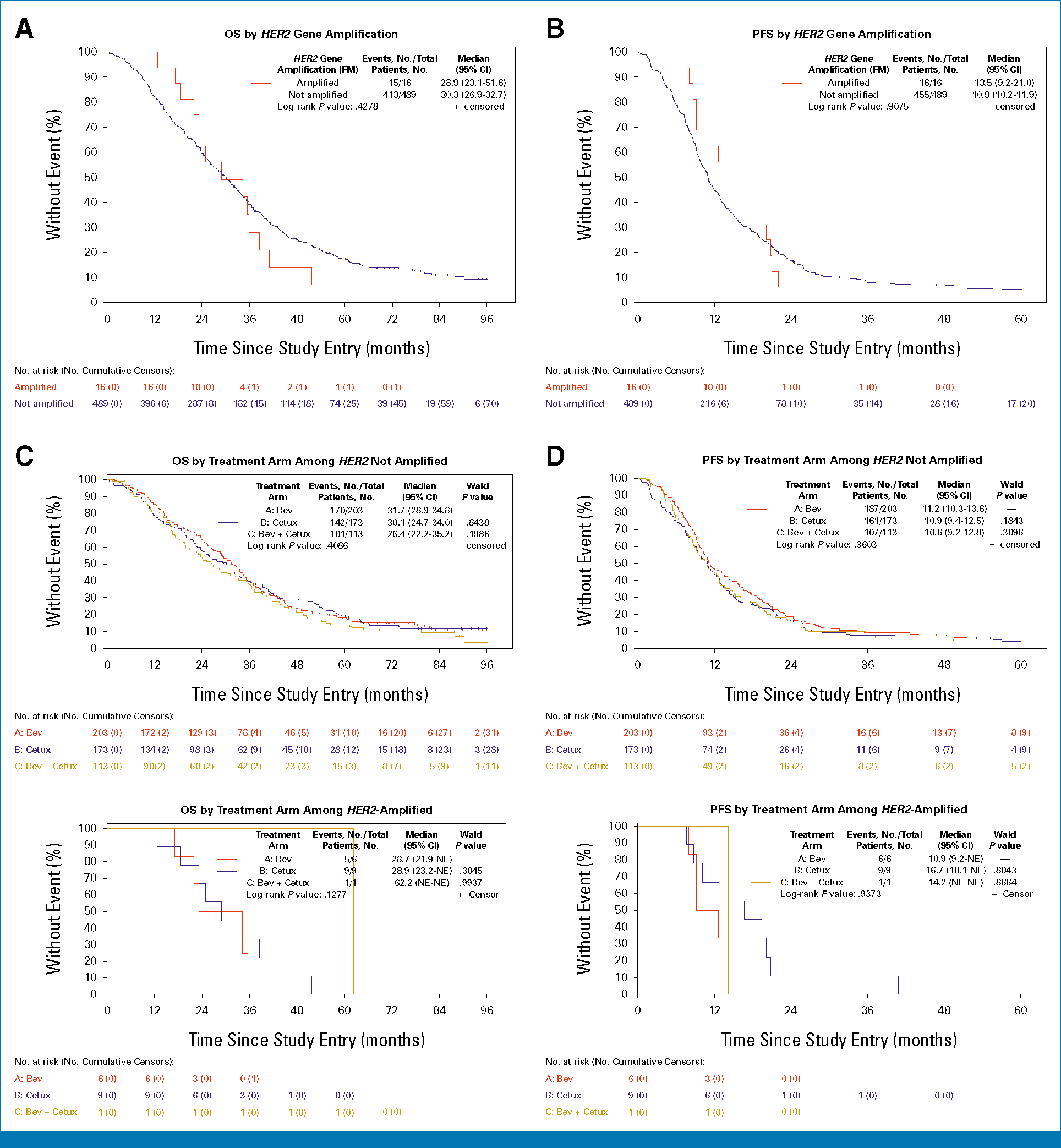

Overall, HER2 amplification was not prognostic for OS (28.9 v 30.3 months, P = .43), PFS (13.5 v 10.9 months, P = .91; Figs 2A and 2B), or ORR (75.1% v 59.1%, P = .20; Data Supplement, Table S4). No significant associations were observed by treatment arm (Figs 2C and 2D), and HER2 amplification was not predictive (Pintx = .58 for OS and Pintx = .76 for PFS, respectively).

FIG 2.

HER2 amplification is neither prognostic nor predictive for OS or PFS (n = 505). (A) OS and (B) PFS for HER2-amplified versus HER2 not amplified in the cohort of patients with both NanoString and NGS data (n = 505). (C) OS and (D) PFS by treatment arm among each HER2 amplification group. Bev, bevacizumab; CALGB, Cancer and Leukemia Group B; Cetux, cetuximab; FM, foundation medicine; NGS, next-generation sequencing; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

HER2 Expression as the Continuous Variable

When treated as a continuous variable, the relationship between NanoString expression data and OS/PFS was found to have a nonlinear shape (Data Supplement, Fig S1), where a progressive increase in HER2 expression below the median was associated with increasing survival, reaching a plateau for HER2 expression levels above the median.

Overall, higher HER2 expression was associated with better OS (adjusted [model 3] hazard ratio [HR], 0.83 [95% CI, 0.75 to 0.93]; P = .0007), PFS (adjusted [model 3] HR, 0.82 [95% CI, 0.74 to 0.91]; P = .0002), and ORR (adjusted [model 2] odds ratio [OR], 1.27 [95% CI, 1.04 to 1.53]; P = .016) when the expression was less than the median value (Table 3). However, the association attenuated above the median level of expression, that is, a higher than median expression, did not associate with the additional improvement in OS, PFS, and ORR. In patients with tumor HER2 expression lower than median, treatment with cetuximab was associated with worse PFS (adjusted [model 3] HR [at expression = Q1], 1.38 [95% CI, 1.12 to 1.71]; P = .0027) and OS (adjusted [model 2] HR [at expression = Q1], 1.28 [95% CI, 1.02 to 1.60]; P = .03) compared with bevacizumab although the association with OS diminished after adjusting for RAS/BRAF and MSI status (Table 4). The association with ORR was not statistically significant in this case. Nevertheless, the interaction between HER2 expression and the treatment arm was statistically significant for each treatment outcome: OS (Pintx = .017), PFS (Pintx = .048), and ORR (Pintx = .001).

TABLE 3.

Prognostic Effect of HER2 Expression in the NanoString Cohort

| Prognostic Effect | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2 (NanoString) | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |||

| HRf (95% CI)e | P | HRf (95% CI)e | P | HRf (95% CI)e | P | |

| OS | ||||||

| .0014 d | .0003 d | .0027 d | ||||

| Above median | 1.000 (0.997 to 1.004) | .8883 | 1.001 (0.998 to 1.005) | .4725 | 1.002 (0.998 to 1.005) | .3075 |

| Below median | 0.826 (0.745 to 0.916) | .0003 | 0.803 (0.722 to 0.893) | <.0001 | 0.832 (0.747 to 0.926) | .0007 |

| PFS | ||||||

| .0001 d | .0001 d | .0007 d | ||||

| Above median | 1.001 (0.998 to 1.004) | .5036 | 1.001 (0.998 to 1.004) | .4851 | 1.002 (0.999 to 1.005) | .2762 |

| Below median | 0.809 (0.733 to 0.892) | <.0001 | 0.806 (0.728 to 0.891) | <.0001 | 0.822 (0.743 to 0.910) | .0002 |

| Overall response | ||||||

| .0399 d | .0545 d | .1707d | ||||

| Above median | 1.000 (0.994 to 1.006) | .9772 | 0.999 (0.993 to 1.005) | .7902 | 0.998 (0.992 to 1.005) | .5822 |

| Below median | 1.274 (1.055 to 1.537) | .0117 | 1.267 (1.045 to 1.535) | .0159 | 1.204 (0.989 to 1.467) | .0648 |

NOTE. Bold entries identify significant P values.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; MSI, microsatellite instability; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status.

Model includes NanoString (linear spline with one knot at median).

Model additionally includes arm, age, chemotherapy, previous adjuvant therapy, previous radiation therapy, race, sex, number of metastatic sites, PS, tumor sidedness, and synchronous/metachronous.

Model additionally includes BRAF, RAS, and MSI.

Test to evaluate the prognostic effect of HER2 expression by comparing a model with HER2 expression with a reduced model without HER2 expression, whereas all other covariates remain the same (a 2 degree-of-freedom test).

Per 100-unit increase.

Odds ratio from the logistic regression model used for overall response.

TABLE 4.

Predictive Effect of HER2 Expression in the NanoString Cohort

| Predictive Effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arm Comparison | HER2g (NanoString) | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c | |||

| HRh (95% CI)f | P | HRh (95% CI)f | P | HRh (95% CI)f | P | ||

| OS | |||||||

| .0673d | .0102 d | .0174 d | |||||

| .0271 | .6471e | .0082 | 0.2394e | .0163 | 0.2037e | |||||

| Cetux v Bev | Q1 = 3.4873 | 1.300 (0.992 to 1.702) | .0568 | 1.278 (1.024 to 1.596) | .0301 | 1.229 (0.982 to 1.538) | .0720 |

| Cetux v Bev | Q2 = 4.5554 | 0.909 (0.679 to 1.216) | .5193 | 0.902 (0.704 to 1.155) | .4119 | 0.895 (0.699 to 1.147) | .3816 |

| Cetux v Bev | Q3 = 6.1281 | 0.906 (0.678 to 1.210) | .5050 | 0.895 (0.700 to 1.144) | .3756 | 0.888 (0.695 to 1.136) | .3447 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q1 = 3.4873 | 1.315 (0.963 to 1.794) | .0847 | 1.243 (0.961 to 1.607) | .0975 | 1.230 (0.950 to 1.594) | .1165 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q2 = 4.5554 | 1.253 (0.895 to 1.753) | .1890 | 1.214 (0.912 to 1.617) | .1833 | 1.292 (0.969 to 1.723) | .0810 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q3 = 6.1281 | 1.203 (0.877 to 1.650) | .2510 | 1.192 (0.914 to 1.556) | .1949 | 1.278 (0.978 to 1.670) | .0725 |

| PFS | |||||||

| .0641 d | .0570 d | .0480 d | |||||

| .0200 | .9879e | .0193 | .8311e | .0173 | .7102e | |||||

| Cetux v Bev | Q1 = 3.4873 | 1.401 (1.080 to 1.817) | .0110 | 1.361 (1.102 to 1.679) | .0041 | 1.384 (1.119 to 1.711) | .0027 |

| Cetux v Bev | Q2 = 4.5554 | 0.969 (0.735 to 1.279) | .8251 | 1.016 (0.804 to 1.285) | .8925 | 1.026 (0.811 to 1.299) | .8294 |

| Cetux v Bev | Q3 = 6.1281 | 0.969 (0.736 to 1.276) | .8234 | 1.015 (0.804 to 1.281) | .8995 | 1.024 (0.811 to 1.293) | .8415 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q1 = 3.4873 | 1.154 (0.854 to 1.558) | .3516 | 1.097 (0.853 to 1.409) | .4716 | 1.117 (0.869 to 1.436) | .3880 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q2 = 4.5554 | 1.227 (0.879 to 1.712) | .2290 | 1.223 (0.921 to 1.624) | .1642 | 1.373 (1.028 to 1.833) | .0319 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q3 = 6.1281 | 1.177 (0.870 to 1.594) | .2909 | 1.189 (0.920 to 1.537) | .1855 | 1.325 (1.022 to 1.718) | .0339 |

| Overall response | |||||||

| .1192d | .0281 d | .0097 d | |||||

| .0504 | 0.3007e | .0089 | 0.3165e | .0029 | 0.2381e | |||||

| Cetux v Bev | Q1 = 3.4873 | 0.961 (0.690 to 1.339) | .8155 | 0.879 (0.673 to 1.147) | .3415 | 0.849 (0.647 to 1.113) | .2352 |

| Cetux v Bev | Q2 = 4.5554 | 1.415 (0.981 to 2.041) | .0629 | 1.327 (0.988 to 1.782) | .0597 | 1.367 (1.013 to 1.846) | .0409 |

| Cetux v Bev | Q3 = 6.1281 | 1.287 (0.909 to 1.822) | .1547 | 1.264 (0.953 to 1.677) | .1046 | 1.288 (0.966 to 1.717) | .0846 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q1 = 3.4873 | 1.010 (0.691 to 1.476) | .9589 | 1.174 (0.863 to 1.597) | .3056 | 1.216 (0.887 to 1.666) | .2239 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q2 = 4.5554 | 0.860 (0.549 to 1.346) | .5086 | 0.992 (0.702 to 1.403) | .9642 | 0.924 (0.648 to 1.318) | .6642 |

| Cetux + Bev v Bev | Q3 = 6.1281 | 1.051 (0.711 to 1.553) | .8026 | 1.102 (0.808 to 1.503) | .5403 | 1.050 (0.765 to 1.442) | .7609 |

Abbreviations: Bev, bevacizumab; Cetux, cetuximab; HR, hazard ratio; MSI, microsatellite instability; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PS, performance status; Q1, first quartile (ie, 25th percentile); Q3, third quartile (ie, 75th percentile).

Model includes NanoString (linear spline with one knot at median), treatment arm, and NanoString × arm.

Model additionally includes age, chemotherapy, previous adjuvant therapy, previous radiation therapy, race, sex, number of metastatic sites, PS, tumor sidedness, and synchronous/metachronous.

Model additionally includes BRAF, RAS, and MSI.

Interaction test on NanoString × arm (arms A and B only), a 2 degree-of-freedom test.

Interaction tests on NanoString × arm (arms A and B only) for each segment of NanoString (below and above median). Each test is a 1 degree-of-freedom test.

Per 100-unit increase.

Expression level after scaling (ie, divided by 100).

Odds ratio from the logistic regression model used for overall response.

In a sensitivity analysis where the model was applied to patients with both HER2 amplification and gene expression data (n = 453), HER2 expression had an additional prognostic and predictive effect for both OS and PFS independent of the amplification status, which held true even after adjusting for multiple covariates (Data Supplement, Tables S5 and S6). Among patients with HER2 not amplified tumors, higher HER2 expression was associated with better OS (adjusted [model 3] P = .016) and PFS (adjusted [model 3] P = .027) when the expression was less than median. In patients with no HER2 amplification and tumor HER2 expression lower than median, treatment with cetuximab was associated with worse PFS (adjusted [model 3] P = .005) and OS (adjusted [model 2] P = .04) compared with that with bevacizumab. No significant associations were observed with tumor expression higher than median regardless of HER2 amplification status. It has to be noted that only one patient within our study population was identified as HER2-amplified with HER2 tumor expression lower than median, and hence, no comparisons were performed for this group.

A second sensitivity analysis of RAS/BRAF WT and non–MSI-H tumors and a third sensitivity analysis of patients receiving either bevacizumab or cetuximab in the NanoString cohort showed similar patterns (Data Supplement, Tables S7–S10).

DISCUSSION

In CALGB/SWOG 80405, tumor HER2 gene expression was predictive and prognostic in patients with mCRC receiving first-line therapy. Overall, patients with tumor HER2 expression higher than median had longer OS and PFS, as well as higher ORR, compared with those with lower expression regardless of treatment. However, when PFS and OS were evaluated by treatment arm on the basis of HER2 expression levels, patients in the high expression group treated with cetuximab showed a longer OS compared with those treated with bevacizumab, whereas patients in the low expression group receiving cetuximab had a shorter PFS. Interestingly, the association between HER2 expression and outcomes showed a nonlinear association in our analysis, demonstrating that OS/PFS/ORR benefit increased with the HER2 expression increase until the median value was reached and then this effect diminished when HER2 expression was higher than median. Conversely, HER2 amplification was neither predictive nor prognostic in our series. To our knowledge, this is the largest analysis of HER2 molecular profiling (ie, HER2 gene amplification and gene expression by NGS and NanoString) in patients with mCRC treated with standard therapy. Previous studies addressing the potential prognostic value of HER2 amplification/overexpression yielded inconsistent results, suggesting either a trend toward worse survival or no prognostic effects,21–23 with the exception of the CALGB 80203 (Alliance) where a dedicated analysis on gene expression markers of efficacy and resistance to cetuximab-based treatment showed that high tumor mRNA levels of HER2 were associated with longer PFS.24 These studies were largely based on HER2 testing by IHC and/or ISH, using heterogeneous HER2 scoring criteria across studies, and mostly focused on early-stage disease or a combination of different tumor stages. In fact, the assessment of the prognostic effect of tumor HER2 amplification/overexpression in CRC is hindered by the low incidence of these alterations, an issue that we also encountered in our series where the prevalence of HER2-amplified tumors was 3%. The low prevalence of tumor HER2 amplification may explain why we did not find any association with patient and treatment outcomes. Hence, gene expression analysis may provide a more effective biomarker for patient selection and stratification. Of note, HER2 amplification significantly correlated with HER2 gene expression in our cohort, and previous studies report high concordance between HER2 molecular profiling using NGS, IHC, and chromogenic ISH/FISH.25–27 Tumor gene expression profiling of HER2 offers the additional advantage of capturing the effect of a wider range of genome alterations enhancing the understanding of cross talk between activated pathways.

The mechanism behind the observed nonlinear association of HER2 expression with patient outcomes is still unclear and opens the question of how to select the optimal cutoff for its use as a candidate biomarker on a larger scale moving forward. The use of a linear spline with one knot to model HER2 expression in our study may seem unusual, but it has several advantages. Most importantly, it avoids the loss of power by dichotomizing the variable and sheds light on the nonlinear relationship between HER2 expression and outcomes.28 The challenge of doing so is that the interpretation of the effect is more complicated than a simple dichotomized variable given the complex relationship. Nevertheless, our results open new perspectives on the role of HER2 expression in mCRC, particularly in those tumors with no HER2 amplification and HER2 expression below the median. This is even more relevant for patients receiving cetuximab-based treatments. In fact, HER2 amplification has been reported as a negative predictor of response to EGFR inhibitors on the basis of retrospective series and preclinical evidence.16,17,29,30 Interestingly, however, a previous study reported the existence of three distinct subgroups of patients with differential response to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies depending on HER2 gene copy number as detected by FISH in KRAS WT mCRC.31 In this series, the presence of partial HER2 amplification was associated with better outcomes compared with FISH-positive and the absence of HER2 imbalance. The authors suggest that HER2 deregulation can be linked to discordant disease behavior depending on the proportion of cells that carry the alteration, reflecting the coexistence of different underlying oncogenic drivers. Notably, none of these studies evaluated HER2 at the gene expression level, which allows for a more granular assessment of the association with outcomes in a setting where the threshold for prognosis and response to anti-EGFR agents has not been established yet. In our series, we found that in patients with tumor HER2 expression lower than median, first-line treatment with cetuximab was associated with worse PFS and OS compared with that with bevacizumab. Early studies suggest that HER2 protein expression can enhance sensitivity and response to growth stimulation by EGFR ligands.32,33 Indeed, specific ligand binding can trigger either homo- or heterodimerization of EGFR with other HER receptors, and cross talk between HER receptors can modulate distinct downstream signaling cascades.34 HER2 is the preferred binding partner for the other members of the family, and HER2 heterodimers produce stronger intracellular signals as compared with other combinations.33 In this context, a higher HER2 gene expression could determine increased HER2 availability to form EGFR/HER2 heterodimers, thus potentially promoting higher dependency on EGFR signaling and consequently increased sensitivity to EGFR inhibitors. On the other hand, HER2 overexpression can trigger EGFR-independent cell proliferation and survival, which may help to explain our observation of a nonlinear association between HER2 expression and treatment outcomes. Further molecular studies are warranted to characterize the underlying complex signaling interactions and understand the biologic changes related to different levels of HER2 gene expression in CRC.

Finally, several studies have reported a differential distribution of HER2 amplification on the basis of clinical and pathologic features of the tumor, including the primary tumor location, with HER2 overexpression/amplification being more frequently found in distal tumors.22,35 A prognostic and predictive association between tumor sidedness and patient outcomes has been recently established in mCRC, with left-sided tumors showing better prognoses and improved treatment outcomes with the use of EGFR inhibitors in addition to combination chemotherapy.36,37 In our cohort, no significant association was observed between HER2 expression/HER2 amplification and known patient/tumor characteristics including tumor location, except for a lower incidence of BRAF mutations in the high HER2 expression group and an association of HER2 amplification with RAS WT and MSS status consistent with other previous reports.

Limitations of our study include the retrospective nature of the analysis and the low number of HER2-amplified tumors in our study population. In addition, our study lacks HER2 IHC and ISH/FISH data to correlate with our gene expression analysis. Another limitation is that the gene expression threshold used in the study was derived internally from our data set. To use HER2 expression as a predictive biomarker in the clinical setting, future prospective validations are necessary to determine the appropriate cut point and to align expression readouts from different platforms.

Our results provide novel insights into the predictive and prognostic values of HER2 gene expression in patients treated with cetuximab- and bevacizumab-based regimens, suggesting a role of HER2 expression in modulating tumor response to anti-EGFR treatment. The observed survival benefit for high versus low HER2 expression was 32 versus 25.3 months, with an increase in ORR and a 1.6-month difference in PFS. In addition, we were able to show a PFS delta of 1.8 months favoring bevacizumab in patients with low HER2 expression. This is meaningful since CALGB/SWOG 80405 did not find any significant difference in PFS in its primary analysis2 and neither did a second large first-line head-to-head trial, the FIRE-3 study.38 Our observed survival differences in patients stratified by HER2 expression compare with results valued as clinically significant in other first-line phase III trials. However, this article focuses on biomarker discovery, the contribution of HER2 expression in risk stratification will need to be measured, and potential utility for treatment decision making will need to be validated before bringing this to clinical practice. Once validated, these findings could inform patient selection and the design of more effective treatment options particularly for patients with low HER2 expression who appear to not benefit from anti-EGFR agents.

Supplementary Material

CONTEXT.

Key Objective

Is HER2 tumor gene expression a biomarker for targeted treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC)?

Knowledge Generated

Patients receiving first-line treatment within the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB)/SWOG 80405 trial with tumor HER2 expression higher than median had longer overall survival, progression-free survival, and higher objective response rates. mCRC tumors with HER2 expression lower than median had worse PFS and OS when treated with cetuximab compared with bevacizumab.

Relevance (E.M. O’Reilly)

Secondary analyses from CALGB/SWOG 80405 provide insight into treatment paradigms for patients with HER2 high and low gene expression in metastatic colon cancer and inform tailored treatment opportunity.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Eileen M. O’Reilly, MD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all the patients and physicians contributing to the establishment of the analyzed data set.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers U10CA180821 and U10CA180882 (to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology), UG1CA233253, UG1CA233180, UG1CA233337, UG1CA233373; U10CA180888, and UG1CA180830 (SWOG). Also supported in part by funds from BMS, Genentech, Pfizer, and Sanofi (https://acknowledgments.alliancefound.org).

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01507.

DISCLAIMER

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, May 29-June 2, 2020 (virtual format).

CLINICAL TRIAL INFORMATION

NCT00265850. Now part of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (Alliance).

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Deidentified patient data and data dictionary are available via NCTN data archive (https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/) or Alliance data sharing (https://www.allianceforclinicaltrialsinoncology.org/main/public/standard.xhtml?path5%2FPublic%2FDatasharing).

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. : Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 73:17–48, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, et al. : Effect of first-line chemotherapy combined with cetuximab or bevacizumab on overall survival in patients with KRAS wild-type advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 317:2392–2401, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, et al. : Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 11:753–762, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, Rowland A, et al. : Extended RAS mutations and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody survival benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Oncol 26:13–21, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allegra CJ, Rumble RB, Hamilton SR, et al. : Extended RAS gene mutation testing in metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Provisional Clinical Opinion update 2015. J Clin Oncol 34:179–185, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, et al. : Resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer: From heterogeneity to convergent evolution. Cancer Discov 4:1269–1280, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertotti A, Papp E, Jones S, et al. : The genomic landscape of response to EGFR blockade in colorectal cancer. Nature 526:263–267, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rachiglio AM, Lambiase M, Fenizia F, et al. : Genomic profiling of KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer patients reveals novel mutations in genes potentially associated with resistance to anti-EGFR agents. Cancers (Basel) 11:859, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RM, Qu X, Lin CF, et al. : ARID1A mutations confer intrinsic and acquired resistance to cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun 13:5478, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartore-Bianchi A, Lonardi S, Martino C, et al. : Pertuzumab and trastuzumab emtansine in patients with HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer: The phase II HERACLES-B trial. ESMO Open 5: e000911, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosi F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Lonardi S, et al. : Long-term clinical outcome of trastuzumab and lapatinib for HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 19:256–262.e2, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Marsoni S, et al. : Targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) oncogene in colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 29:1108–1119, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Comprehensive Cancer Network: National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Colon Cancer Version 3.2023. https://www.nccn.org [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valtorta E, Martino C, Sartore-Bianchi A, et al. : Assessment of a HER2 scoring system for colorectal cancer: Results from a validation study. Mod Pathol 28:1481–1491, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sartore-Bianchi A, Trusolino L, Martino C, et al. : Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type, HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): A proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 17:738–746, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sartore-Bianchi A, Amatu A, Porcu L, et al. : HER2 positivity predicts unresponsiveness to EGFR-targeted treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist 24:1395–1402, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raghav K, Loree JM, Morris JS, et al. : Validation of HER2 amplification as a predictive biomarker for anti–epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 10.1200/PO.18.00226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randon G, Pietrantonio F: Towards multiomics-based dissection of anti-EGFR sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 29:4021–4023, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. : New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92:205–216, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenz H-J, Ou F-S, Venook AP, et al. : Impact of consensus molecular subtype on survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 37: 1876–1885, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richman SD, Southward K, Chambers P, et al. : HER2 overexpression and amplification as a potential therapeutic target in colorectal cancer: Analysis of 3256 patients enrolled in the QUASAR, FOCUS and PICCOLO colorectal cancer trials. J Pathol 238:562–570, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingold Heppner B, Behrens HM, Balschun K, et al. : HER2/neu testing in primary colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 111:1977–1984, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawada K, Nakamura Y, Yamanaka T, et al. : Prognostic and predictive value of HER2 amplification in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 17:198–205, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sepulveda AR, Hamilton SR, Allegra CJ, et al. : Molecular biomarkers for the evaluation of colorectal cancer: Guideline from the American Society for Clinical Pathology, College of American Pathologists, Association for Molecular Pathology, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 35:1453–1486, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cenaj O, Ligon AH, Hornick JL, et al. : Detection of ERBB2 amplification by next-generation sequencing predicts HER2 expression in colorectal carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 152:97–108, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada Y, Yagi R, Kameyama H, et al. : Utility of comprehensive genomic sequencing for detecting HER2-positive colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol 66:1–9, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujii S, Magliocco AM, Kim J, et al. : International harmonization of provisional diagnostic criteria for ERBB2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer allowing for screening by next-generation sequencing panel. JCO Precis Oncol 10.1200/PO.19.00154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman DG, Royston P: The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ 332:1080, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertotti A, Migliardi G, Galimi F, et al. : A molecularly annotated platform of patient-derived xenografts (“xenopatients”) identifies HER2 as an effective therapeutic target in cetuximab-resistant colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 1:508–523, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yonesaka K, Zejnullahu K, Okamoto I, et al. : Activation of ERBB2 signaling causes resistance to the EGFR-directed therapeutic antibody cetuximab. Sci Transl Med 3:99ra86, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin V, Landi L, Molinari F, et al. : HER2 gene copy number status may influence clinical efficacy to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer 108: 668–675, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kurbel S: Are HER1/EGFR interactions with ligand free HER2 related to the effects of HER1-targeted drugs? Med Hypotheses 67:1355–1357, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin I, Yarden Y: The basic biology of HER2. Ann Oncol 12:S3–S8, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wee P, Wang Z: Epidermal growth factor receptor cell proliferation signaling pathways. Cancers (Basel) 9:52, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salem ME, Weinberg BA, Xiu J, et al. : Comparative molecular analyses of left-sided colon, right-sided colon, and rectal cancers. Oncotarget 8:86356–86368, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, et al. : Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol 28:1713–1729, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, et al. : The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 70:87–98, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. : FOLFIRI plus cetuximab or bevacizumab for advanced colorectal cancer: Final survival and per-protocol analysis of FIRE-3, a randomised clinical trial. Br J Cancer 124:587–594, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified patient data and data dictionary are available via NCTN data archive (https://nctn-data-archive.nci.nih.gov/) or Alliance data sharing (https://www.allianceforclinicaltrialsinoncology.org/main/public/standard.xhtml?path5%2FPublic%2FDatasharing).