Abstract

Optimal expansion of influenza virus nucleoprotein (DbNP366)-specific CD8+ T cells following respiratory challenge of naive Ig−/− μMT mice was found to require CD4+ T-cell help, and this effect was also observed in primed animals. Absence of the CD4+ population was consistently correlated with diminished recruitment of virus-specific CD8+ T cells to the infected lung, delayed virus clearance, and increased morbidity. The splenic CD8+ set generated during the recall response in Ig−/− mice primed at least 6 months previously showed a normal profile of gamma interferon production subsequent to short-term, in vitro stimulation with viral peptide, irrespective of a concurrent CD4+ T-cell response. Both the magnitude and the localization profiles of virus-specific CD8+ T cells, though perhaps not their functional characteristics, are thus modified in mice lacking CD4+ T cells.

Whether or not CD4+ T-cell help is required to promote the CD8+ T-cell response may vary for different virus infections (4, 9, 10, 11, 18). Several mechanisms accounting for these differences have been elucidated using a variety of systems. For instance, if the virus infection directly upregulates costimulatory molecules (such as B7-1 and B7-2) on dendritic cells (23), the need for CD4+ T cells can be bypassed, perhaps due to increased interleukin-2 production by the CD8+ T cells themselves (7, 13). Also, cognate interaction between CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells can lead to subsequent signaling through CD40 and cross-priming of the CD8+ response (3). Limiting dilution analysis (LDA) to determine cytotoxic T-lymphocyte precursor (CTLp) frequencies in CD4-deficient major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II−/− mice indicated that the extent of clonal expansion for the CD8+ population was diminished following primary respiratory challenge with the HKx31 (H3N2) influenza A virus, though not with the parainfluenza type 1 virus, Sendai virus (8, 22). However, potent, influenza virus-specific CTL effector populations were detected in the pneumonic lung, and virus clearance was only slightly delayed in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help (22). The overall conclusion was that a smaller CTLp pool in the influenza virus-infected MHC class II−/− mice is fully used to achieve efficient elimination of the pathogen.

These experiments have been interpreted as evidence that CD8+ T cells, acting alone, can function to terminate an influenza A virus infection. However, there is the caveat that the MHC class II−/− mice can still mount an immunoglobulin M (IgM) response which, though virus-specific IgG is clearly much more effective (14, 15, 20), could act to reinforce CD8+ T-cell-mediated control by neutralizing free virus. We have thus looked at the question again, using monoclonal antibody (MAb) treatment (2) to deplete the CD4+ subset in naive Ig−/− μMT mice throughout the course of virus challenge (12). The analysis has also been extended to quantify the need, or otherwise, for CD4+ T help in previously primed μMT mice, which make both a strong CD4+ T-cell response to the HKx31 influenza A virus and establish CD4+ T-cell memory in the long term (21). The LDA approach used to quantitate the CD8+ response in the previous experiments with MHC class II−/− mice has been supplanted by direct staining with tetrameric complexes of MHC class I glycoprotein plus peptide (tetramers), which gives a much more accurate measure of virus-specific T-cell numbers (5, 16).

Experimental procedures.

The Ig−/− μMT mice backcrossed to the C57BL/6J (B6) background (12) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine, and established as a colony at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. Female (8- to 10-week-old) mice were anesthetized and infected intranasally (i.n.) with 106.8 50% egg infectious doses (EID50) of the HKx31 influenza A virus (2), either to monitor the host response and virus clearance (primary challenge) or to establish immune memory prior to a further HKx31 challenge (secondary challenge). Other mice were primed by intraperitoneal exposure to 107.9 EID50 of the A/PR8/34 (PR8, H1N1) virus, the source of the internal proteins of HKx31 which was generated as a laboratory recombinant. At least 1 month elapsed between priming and challenge. Depletion of the CD4+ subset was done by a well-established protocol (2) that requires dosing every 2 to 3 days (commencing prior to challenge) with MAb GK1.5 or a control rat Ig. The efficacy of the GK1.5 treatment was checked at each sampling by flow cytometric analysis using a noncompetitive MAb to CD4 (RM4-4; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.) and consistently showed <0.1% CD4+ T cells in spleen samples from the depleted mice.

At the time of sampling, the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), mediastinal lymph node (MLN), and spleen populations were taken to measure the magnitude of the virus-specific CD8+ T-cell response, while the lungs were homogenized in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline for virus titration in embryonated hen eggs. All virus titers are expressed as log10 EID50 per 100 μl of lung homogenate. The number of influenza virus nucleoprotein (NP)-specific CD8+ T cells was determined (5) by concurrent staining with a MAb to CD8α and the DbNP366 tetramer, or by in vitro stimulation with the NP366–374 peptide for 5 h in the presence of brefeldin A, followed by fixation and staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated MAb XMG1.2 (Pharmingen) to gamma interferon (IFN-γ). The analysis was done with a FACScan and Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Consequences of CD4 depletion for the primary response.

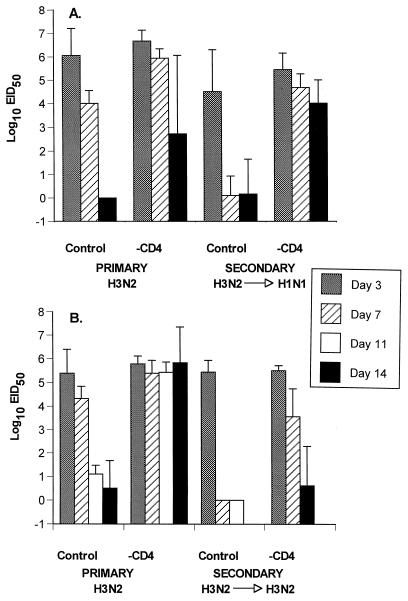

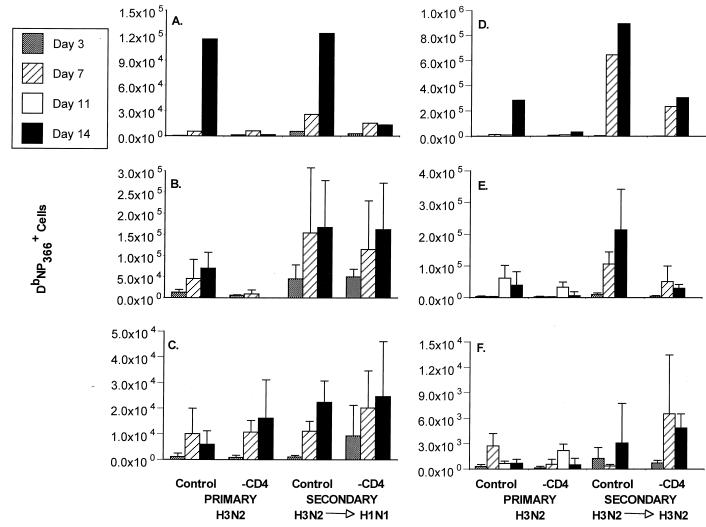

The HKx31 influenza A virus is generally eliminated from the respiratory tract of conventional B6 mice by day 10 after i.n. challenge (6). The profile in the Ig−/− mice was essentially identical, with minimal (or no) virus being detected at day 14 in those with an intact CD4+ T-cell compartment; however, the infection was controlled more slowly in the absence of the CD4+ subset (Fig. 1). The pattern of delayed virus clearance for the treatment group reflected diminished recruitment of DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells to the BAL (Fig. 2A and D) and smaller responses in the spleen (Fig. 2B and E), though this effect was not obvious for the regional MLN (Fig. 2B and E). The net consequence was that the CD4-depleted Ig−/− mice were much more susceptible to this relatively nonlethal influenza virus and had high mortality rates (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Virus titers in lung homogenates (log10 EID50/100 μl) recovered from Ig−/− μMT mice during a primary or secondary response in the presence or absence of CD4+ T cells. The secondary-challenge mice (5) were primed more than 1 month previously with either the PR8 (H1N1) (A) or HKx31 (H3N2) (B) influenza A virus and then challenged i.n. with the H3N2 virus. Some (−CD4) were depleted of CD4+ T cells (2), while others (control) were treated with an irrelevant MAb. Groups of four to five mice were assayed at each time point, and the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The secondary response was not assayed on day 11. The “0” results are included to show that the mice were sampled, but no virus was recovered.

FIG. 2.

The primary and secondary CD8+ T-cell response to DbNP366 in control and CD4-depleted Ig−/− μMT mice. The secondary-challenge mice (4) were primed more than 1 month previously with either the PR8 (H1N1; (A to C) or HKx31 (H3N2; D to F) influenza A virus and then challenged i.n. with the H3N2 virus. These are the same experiments as those illustrated in Fig. 1, which gives virus titers in lungs. The BAL populations (A and D) were pooled, and the spleen (B and E) and MLN (C and F) samples (mean ± standard deviation) were assayed as individuals. The numbers of virus-specific CD8+ T cells were calculated from the percent staining for both CD8α and DbNP366 and the total cell counts (5).

TABLE 1.

Consequences of depleting CD4+ T cells for the survival of Ig−/− μMT mice following i.n. challenge with the HKx31 virusa

| Virus priming | CD4 depletionb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| − | + | |

| Nil | 91 | 46 |

| H1N1 | 89 | 67 |

| Nil | 100 | 34 |

| H3N2 | 93 | 59 |

The analysis was done exactly as described in the text. Group sizes ranged from 9 to 38 mice, and the study was terminated at day 14 after infection.

Numbers represent percent survival.

Effect in previously primed mice.

The recall CD8+ T-cell response was analyzed for intact μMT mice that had been primed with the PR8 (H1N1) or HKx31 (H3N2) virus, rested for at least a month, and then depleted of the CD4+ set immediately before (and during) secondary challenge with the H3N2 virus. Mortality rates in the CD4-depleted immune mice were not as high as those for the primary animals, but survival in these groups was still less than that for the comparable controls (Table 1). Again, the more rapid virus elimination characteristic of established CD8+ T-cell memory (6, 17) was compromised in the absence of the CD4+ subset (Fig. 1). As in the primary response, fewer DbNP366-specific CD8+ T cells were recruited to the lung in the mice lacking CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A and D). The CD8+ DbNP366 response in the spleen was significantly reduced (P < 0.01) in one (H3N2→H3N2), but not the other (H3N2→H1N1), group of CD4-depleted mice compared to the control groups (Fig. 2B and E). Again, there was no obvious effect on the numbers of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the MLN (Fig. 2C and F). Perhaps the difference in spleen findings between the H1N1- and H3N2-immune mice (Fig. 2B and E) reflects that the recall CD4+ T-cell response was more effectively primed by prior exposure to the H3N2 challenge virus, since other experiments indicate that most of the virus-specific CD4+ T cells are specific for epitopes derived from the H3 molecule (J. Riberdy, unpublished data). Certainly, the recruitment to the lung is much greater in H3N2-immune mice during secondary challenge with a homologous virus (Fig. 2A and D). Despite the difference in recruitment to the lung, virus is cleared from the lung at similar rates (Fig. 1).

IFN-γ production by secondarily stimulated CD8+ T cells.

Earlier experiments with one (25), but not another (18), model of persistent virus infection under conditions of CD4+ T-cell deficiency indicated that these continually activated virus-specific CD8+ T cells progressively lose the capacity to synthesize IFN-γ after in vitro stimulation with a high dose of the appropriate peptide (24). The HKx31 (H3N2) influenza A virus could not be recovered from the lungs of Ig−/− mice sampled at 30, 60, or 90 days after infection (21; D. J. Topham, personal communication), and so this model allows us to analyze the nature of the recall response from a resting CD8+ memory T-cell population in the absence of concurrent CD4+ T help.

Splenic CD8+ T cells from Ig−/− mice that had been primed i.n. 6 or 12 months previously with the H3N2 virus were infected i.n. again with the same virus and then analyzed for the capacity to synthesize IFN-γ following in vitro restimulation with the NP366–374 peptide (Table 2). Secondary stimulation of these influenza virus-immune Ig−/− mice in the absence of a concurrent CD4+ T-cell response in no way modified the profile of IFN-γ production for the responding CD8+ set (Table 2). However, as observed in the early experiment with mice that had been given the first dose of the H3N2 virus only 1 month before a further H3N2 challenge (Fig. 2E), the numbers of virus-specific CD8+ DbNP366+ T cells generated in the spleen were significantly diminished in the CD4-depleted group.

TABLE 2.

Effect of CD4 depletion on the spleen recall response in long-term memorya

| Expt | CD4 depletion | Cell count (104)

|

Ratiob | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ DbNP366+ | CD8+ IFN-γ+ | |||

| 1 | − | 144 | 87 | 0.6 |

| + | 19 | 7 | 0.4 | |

| 2 | − | 152 ± 63 | 96 ± 40 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| + | 48 ± 34c | 34 ± 22c | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |

Groups of five (experiment 1) or six (experiment 2) μMT were challenged i.n. with the HKx31 virus at 6 (experiment 2) or 12 (experiment 1) months after i.n. priming with the same virus. The spleens from experiment 1 were pooled and sampled on day 14 after secondary infection, while those from experiment 2 were sampled on day 10 after secondary infection and processed as individuals.

Ratio of IFN-γ+ to DbNP366+ for the CD8+ set.

Significantly different (P < 0.01 or less) from the (−) group given the rat Ig control.

Conclusions.

We know from previous studies with μMT mice that both naive and primed CD4+ T cells deal very poorly with an influenza virus challenge in the absence of the CD8+ subset (17, 18, 20). Now we have shown that collaboration between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells plays an important role and contributes directly to virus clearance when the CD8 response is intact. The CD4+ T cells clearly operate to promote the extent of clonal expansion for influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleen, though not in the regional MLN. Does this reflect that the MLN is sampling afferent lymph draining directly from the virus-infected lung? Are there virus-induced cytokines or chemokines in this fluid phase that substitute for T-cell help? The HKx31 influenza virus replicates almost exclusively in the respiratory tract and little, if at all, in lymphoid tissue. Also, the spleens of μMT mice are small, lack both follicular dendritic cells and B lymphocytes, and may provide an anatomical environment very different from that encountered in a normal mouse. Nonetheless, optimal recruitment of virus-specific CD8+ T cells to the lung seems to require the presence of CD4+ T cells regardless of what happens in the spleen.

In general, however, these experiments support the conclusion reached from the earlier LDA and CTL analysis with MHC class II−/− mice (22) that CD4+ T-cell help can function to augment the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T-cell response. This is true for naive CD8+ precursors specific for the DbNP366 epitope and for CD8+ memory T cells expanded initially in the context of intact CD4+ T-cell function that were then restimulated in the absence of such help. The latter finding was somewhat surprising, as CD8+ memory T cells are generally considered to be much easier to trigger and to require less cytokine (1, 19). In general, these results suggest that it is important to prime both the CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell compartments to achieve an optimal recall response.

Acknowledgments

These experiments were supported by Public Health Service grants AI29579, AI38359, and CA21765 and by The American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). J.P.C. is the recipient of a fellowship from the Alfred Benzon Foundation, Denmark.

We thank Vicki Henderson for help with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allan W, Tabi Z, Cleary A, Doherty P C. Cellular events in the lymph node and lung of mice with influenza. Consequences of depleting CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:3980–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett S R M, Carbone F R, Karamalis F, Flavell R A, Miller J F A P, Heath W R. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1993;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty P C, Allan W, Eichelberger M, Carding S R. Roles of alpha beta and gamma delta T cell subsets in viral immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:123–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flynn K J, Belz G T, Altman J D, Ahmed R, Woodland D L, Doherty P C. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary influenza pneumonia. Immunity. 1998;8:683–691. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn K J, Riberdy J M, Christensen J P, Altman J D, Doherty P C. In vivo proliferation of naive and memory influenza-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8597–8602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding F A, Allison J P. CD28-B7 interactions allow the induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the absence of exogenous help. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1791–1796. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou S, Mo X Y, Hyland L, Doherty P C. Host response to Sendai virus in mice lacking class II major histocompatibility complex glycoproteins. J Virol. 1995;69:1429–1434. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1429-1434.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings S R, Bonneau R H, Smith P M, Wolcott R M, Chervenak R. CD4-positive T lymphocytes are required for the generation of the primary but not the secondary CD8-positive cytolytic T lymphocyte response to herpes simplex virus in C57BL/6 mice. Cell Immunol. 1991;133:234–252. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90194-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson A J, Njenga M K, Hansen M J, Kuhns S T, Chen L, Rodriguez M, Pease L R. Prevalent class I-restricted T-cell response to the Theiler's virus epitope Db:VP2121-130 in the absence of endogenous CD4 help, tumor necrosis factor alpha, gamma interferon, perforin, or costimulation through CD28. J Virol. 1999;73:3702–3708. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3702-3708.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalams S A, Walker B D. The critical need for CD4 help in maintaining effective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2199–2204. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. A B cell-deficient mouse by targeted disruption of the membrane exon of the immunoglobulin mu chain gene. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linsley P S, Brady W, Grosmaire L, Aruffo A, Damle N K, Ledbetter J A. Binding of the B cell activation antigen B7 to CD28 costimulates T cell proliferation and interleukin 2 mRNA accumulation. J Exp Med. 1991;173:721–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozdzanowska K, Furchner M, Maiese K, Gerhard W. CD4+ T cells are ineffective in clearing a pulmonary infection with influenza type A virus in the absence of B cells. Virology. 1997;239:217–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mozdzanowska K, Furchner M, Washko G, Mozdzanowski J, Gerhard W. A pulmonary influenza virus infection in SCID mice can be cured by treatment with hemagglutinin-specific antibodies that display very low virus-neutralizing activity in vitro. J Virol. 1997;71:4347–4355. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4347-4355.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murali-Krishna K, Altman J D, Suresh M, Sourdive D J, Zajac A J, Miller J D, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a re-evaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riberdy J M, Flynn K J, Stech J, Webster R G, Altman J D, Doherty P C. Protection against a lethal avian influenza A virus in a mammalian system. J Virol. 1999;73:1453–1459. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1453-1459.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevenson P G, Belz G T, Altman J D, Doherty P C. Virus-specific CD8+ T cell numbers are maintained during gamma-herpesvirus reactivation in CD4-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15565–15570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabi Z, Lynch F, Ceredig R, Allan J E, Doherty P C. Virus-specific memory T cells are Pgp-1+ and can be selectively activated with phorbol ester and calcium ionophore. Cell Immunol. 1988;113:268–277. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topham D J, Doherty P C. Clearance of an influenza A virus by CD4+ T cells is inefficient in the absence of B cells. J Virol. 1998;72:882–885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.882-885.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Topham D J, Tripp R A, Hamilton-Easton A M, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Quantitative analysis of the influenza virus-specific CD4+ T cell memory in the absence of B cells and Ig. J Immunol. 1996;157:2947–2952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripp R A, Sarawar S R, Doherty P C. Characteristics of the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response in mice homozygous for disruption of the H- 21Ab gene. J Immunol. 1995;155:2955–2959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y, Liu Y. Viral induction of co-stimulatory activity on antigen-presenting cells bypasses the need for CD4+ T-cell help in CD8+ T-cell responses. Curr Biol. 1994;4:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zajac A J, Blattman J N, Murali-Krishna K, Sourdive D J, Suresh M, Altman J D, Ahmed R. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2205–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zajac A J, Murali-Krishna K, Blattman J N, Ahmed R. Therapeutic vaccination against chronic viral infection: the importance of cooperation between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]