All agree that we need to measure the quality of health care, including the care given by individual doctors. Measuring “goodness” requires accurate data used appropriately, and it must be done without demoralising and demotivating staff. Do current measures fulfil these requirements, and if not, what measures should be used?

In the recent Reith lectures (broadcast annually by BBC radio on issues of contemporary interest), Onora O'Neill explored the new age of accountability. She concluded that increasing reliance on measurement reduced trust in health (and other public) services and that professionals and public servants should be“free to serve the public.′1 This will ring true with many.

However, patients, funders, commissioners, provider organisations, and health professionals legitimately want to know just how “good” are individual doctors, teams, and healthcare providing organisations. The traditionally qualitative, anecdotal approach, supplemented by trust, is being increasingly replaced by data on effectiveness, safety, acceptability, and efficiency.

Measurement is crucial for a range of purposes—learning, quality improvement, accountability, and regulation—but must be used appropriately. We contend that measurement can be used to reinforce the natural desire of healthcare staff to improve care at the same time as understanding the quality of the service delivered.

However, creating meaningful information from accurate data to facilitate rational choices is a real challenge. It must be done without distorting staff behaviour or demoralising and demotivating health professionals (including managers), and it must offer true comparisons.

Summary points

Individuals and organisations constantly strive to define and measure quality of health care

Good data on quality of care are needed to achieve understanding and effective change

Data are often used out of context and without taking account of natural variation

A good measure of quality of care is appropriate to that task and is used appropriately

Twelve attributes can be ascribed to quality measures—helpful when choosing indicators

Background

Recently the Institute of Medicine in the United States concluded that “between health care we have and the care we could have is not just a gap but a chasm.”2 An evaluation in a large sample of general practitioners of the use of 29 national (evidence based) guidelines and 282 indicators for primary care in the Netherlands showed that on average 67% of the recommended care was provided to patients.3 Patients' evaluations of primary care collected in 16 countries in Europe with an internationally standardised questionnaire showed that 30-40% of the patients thought that the organisation of services could be better (50% in the United Kingdom).4

These findings support the action of societies, governments, and healthcare organisations in their monitoring of health care for expenditure, value for money, and safety. Doctors, nurses, and other health professionals need to compare themselves with their peers and against external and self generated standards in order to improve care. And crucially, patients need information to make rational choices—is their doctor competent, is their hospital safe, is their treatment optimal?

In particular, both the public and managers want to know which the “good” doctors, teams, and institutions are. They want to protect themselves from the bad and incompetent. Of course, there are many definitions and therefore assessments of good, and any one doctor may be very good in some aspects of care but“poor”in others.

How is “goodness” currently measured?

The Institute of Medicine has recommended improvements in the way that the healthcare system is measured2 as standards, performance, and changes cannot be monitored effectively without secure measures. However, inappropriate measures (and there is no such thing as the perfect or right measure) can result in perverse incentives or justification for data manipulation. If the person or organisation whose performance is being measured feels powerless to influence the indicator, inappropriate measurement can also lead to demotivation, dysfunction, and crisis. Currently, the selection of quality measures is often driven by what can be measured3 rather than by a definition of “goodness” followed by the derivation of an appropriate measure.

Many quality measures, such as revalidation, consultation satisfaction rating, or the “fellowship by assessment” quality assurance programme of the Royal College of General Practitioners, relate to individual health professionals. Others more clearly relate to teams or whole organisations. These include star ratings, assessments by the Commission for Health Improvement, or satisfaction with services.

Examples of measures from the United States include a comprehensive set of quality indicators (developed by researchers at Rand, California), tested for validity and feasibility, that cover many aspects of health care,5 and a set of complex assessments to accredit care—used by the Joint Commission for Accreditation of Health Organisations and the National Committee for Quality Assurance. Other international examples can be found in box B1 on the BMJ 's website (bmj.com).

Official bodies and outside commercial organisations have begun placing data derived from health service self reporting sources in the public domain in ways that make it accessible to patients, managers, researchers, and clinicians. For example, the 60 US hospitals with lowest mortality within 30 days after a myocardial infarction scored lower on patient evaluations of care.6 The hope is that public access to such data will lead to better data, choices, and care, although its impact is still unproved and use by the target groups (patients, other providers, and commissioners) is still limited.7,8

Even though choices are often severely constrained, people can look at local comparisons and in many cases add their own vital contextual understanding in making their choice. Prospective patients must weigh comparative information, such as waiting times and outcomes, keeping in mind their own previous experience and the experience of family, friends, and advisers.

We aspire to a world in which patients are protected by measures of competency; failing teams and organisations can be identified and remedial action taken; patients and their advisers, especially family doctors, can make informed choices of services to use; and service commissioners can deploy resources most efficiently to achieve best care. Finally, the treasury can monitor improvements in care and be held to account by the electorate. This world is currently far from reality.

How should health care be measured?

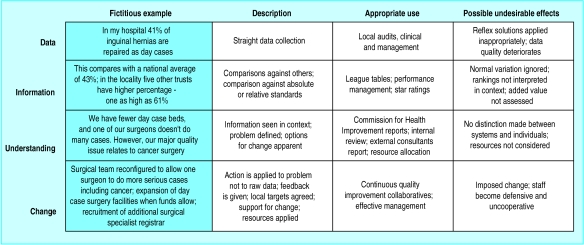

Data on their own are of limited value. Information that compares data with others or against standards is more useful, but without context—and thus understanding—it cannot be applied effectively (figure). Ideally comparisons would be “like with like,” but this rarely happens. Local health needs, service configurations, and case mix all influence data, and this is what is meant by “context.” The easiest way to get good surgical outcomes is to admit only low risk cases; high immunisation rates are much more difficult to achieve in deprived areas.

In the table we suggest 12 attributes to use when appraising quality measures—with examples of current quality measures in the United Kingdom that we believe have or do not have these attributes. For example, surgical waiting times have good face validity, are usually available, and offer a comparison between teams and organisations. They fall down on effectiveness: they measure only part of the patient's experience, such as time on the waiting list for surgery; their reliability is compromised by manipulation; they are usually not adjusted for the context; and it is never clear whether a long waiting list is due to inefficient surgical teams, poor management, or lack of capacity—so, it is unclear if and how the problem can be resolved.

If poor quality measures as defined against the attributes in the table are applied, then perverse incentives and demoralisation of managers and health professionals become a real possibility. One major English trust—the Royal United Hospitals, Bath—had manipulated the number it reported for patients waiting over 15 months for surgery. This is precisely the outcome to be avoided. Another powerful lesson from recent experience with performance indicators is that variation occurs in all systems and that detecting unacceptable or dangerous variation is the key task.9 Not all differences are meaningful.

Lastly, the involvement of service users and the public in developing quality measures is an essential aspect of quality improvement. Although some measures will continue to be technical, there is a shortage of good measures of dimensions of care that are directly relevant to service users and which meet the attributes in the table.

Right tool for the job

Measurement can be used for learning and developing, quality improvement, making informed choices, accountability, contracting, and regulation. In choosing a measure, the purpose must be explicit, alternative measures appraised, and the limitations of the chosen measure openly acknowledged.

In regulation, for example, definitive judgments are needed—a doctor cannot be“slightly”fit to practise—and this requires high face validity, reliability of data (or evidence), and attribution to an individual. Context and interpretation may be used in mitigation, but the key decision is a bipolar judgment: is this behaviour acceptable or unacceptable?

However, many measures of quality are for feeding into the quality improvement cycle (see box B2 on bmj.com). In this setting, it is much more important that the data are understood and are interpreted within the context of the performance. If a town has a high rate of ischaemic heart disease owing to local deprivation, ethnic mix, or population behaviour, its appearance at the bottom of league tables is more likely to create poor morale and apathy than improvement. If, however, the same data are used to measure “health gain”—the level of care or outcome adjusted for the context—teams will understand the context and use them wisely. As the second of Langland's rules states that “measurement for improvement is not measurement for judgment.”10

Teams and individuals are increasingly committed to improving the quality of their care as part of their professional imperative and culture.11 The adoption of clinical audit and reflective practice has been slow,12 but the evidence of its effectiveness is mounting, particularly when the audit is integrated in a more comprehensive approach to improving patient care.13 One cornerstone of healthcare improvement is continual measurement as a tool for understanding systems and determining whether changes are effective.

The way in which data are used (as in figure) is important. At one extreme, simply sending people data on their performance does not create quality improvement. We know that “facilitated feedback” (or “academic detailing”)—that is, using someone trained in interpreting the data to give the feedback—is the most effective way of giving people feedback, but it has to be supported with leadership and resources.

Conclusions

It is right that the public, health professionals, and health service managers want to measure absolute and relative performance—or “goodness”—as a means to improve care and support informed choices. The measures used will meet the ideal attributes to a greater or lesser degree and require value judgments in arriving at a conclusion.

Data should be accurate, measures appropriate, context adjusted for, and interpretation responsible and cautious. That way, stakeholders in health care, especially service users, will be able to make informed choices; good care will be identified and rewarded; and safety will be improved. If healthcare regulators are serious about promoting quality then they must ensure that measures of quality are not misapplied and abused,14 that natural variations in systems are recognised, and that measures are not perceived as capricious tools for shifting responsibility and blame.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Using data for quality improvement and the levels at which they are applied

Table.

Twelve attributes and ideal descriptions of quality measures, with examples from United Kingdom

| Attribute

|

Ideal description

|

Measures with attribute

|

Measures without attribute

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Health professions, managers, and public see meeting the quality measure as better quality (better patient outcomes; more efficient and patient friendly services, etc) | Waiting times; death rates from surgery; readmission rates; complaints and litigation; significant event auditing | Singlehanded general practice |

| Communicable | Relevance of measure can be easily explained and understood by target groups | Prevention uptake rates (for example, cervical cytology or immunisation) | Star rating of NHS trusts |

| Effective | It measures what it purports to measure—so useful for clinicians, public, and managers in making choices and commissioning services; free of perverse incentives | Commission for Health Improvement reports | Waiting times; day surgery rates; revalidation |

| Reliable | Data should be complete, accurate, consistent, and reproducible | Singlehanded general practice | Fellowship by assessment; availability of general practitioner for consultation |

| Objective | Data should be as independent of subjective judgment as possible | Prescribing data | NHS doctor appraisal; Commission for Health Improvement reports |

| Available | Data should be collected for routine clinical or organisational reasons or be available quickly with minimum of extra effort and cost | Prescribing data; star rating of NHS trusts | Long term effects of care; functional status; link between care and outcome |

| Contextual | Measure should be context free or important context effects should be adjusted for | Consultant numbers per 1000 patients with disease | Prevention uptake rates |

| Attributable | How well measure reflects quality of individuals, teams, or organisations must be explicit; measure to be used appropriately in its presentation and interpretation | NHS doctor appraisal; revalidation; fellowship or membership by assessment; quality team development; quality practice award | Waiting times; overall patient satisfaction |

| Interpretation | How well measure reflects health needs, capacity, structures, or performance should be explicit | Bed occupancy | General practitioners' referral rates; prescribing data (PACT) |

| Comparable | Where “gold standard” (for example, NICE guideline, NSF standard or GMC guidance) exists, measure should allow reliable comparison with standard; otherwise comparison should be to other data in similar circumstances | Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; aspirin in ischaemic heart disease or stroke; glycaemic and blood pressure control in diabetes | General practitioners' referral rates |

| Remediable | Need for recognised, accepted, and feasible methods for influencing measure and improving quality, need for resources for intervening; change can be achieved if it is needed | Record keeping | Effects due to deprivation and lifestyle (acute myocardial infarction, smoking rates, obesity); attendance rates at accident and emergency; suicide rates |

| Repeatable | Measure should be sensitive to improvement over time | Staffing levels; bed numbers and occupancy | Complaints and litigation; significant event auditing |

NICE=National Institute for Clinical Excellence; NSF=national service framework; GMC=General Medical Council.

Footnotes

Competing interests: MP is the strategic director of Primary Care Information services (PRIMIS) and is a paid adviser to Dr Foster (http://home.drfoster.co.uk), a guide to local NHS and private healthcare services. TW has been paid for talks and workshops on measurement.

More examples of quality measures can be found on bmj.com

References

- 1. O'Neill A. Called to account. 2002 Reith lectures. www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2002/ (accessed June 2002).

- 2.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grol R. Improving the quality of medical care. JAMA. 2002;286:2578–2585. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grol R. Successes and failures in guideline implementation. Med Care. 2001;39:S2. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108002-00003. (II46-54). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall M, Shekelle P, Brook R, Leatherman S. Dying to know: public release of information about quality of health care. California: Rand; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassirer J. Hospitals, heal yourselves. New Engl J Med. 1999;340:309–310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901283400410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies HT, Marshall M. Public disclosure of performance data: does the public get what the public wants? Lancet. 1999;353:1639–1640. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin N, Marshall M, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. Public disclosure of performance data: learning from the US experience. Q Health Care. 2000;9:53–57. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammed MA, Cheng KK, Rouse A, Marshall T. Bristol, Shipman, and clinical governance: Shewhart's forgotten lessons. Lancet. 2001;357:463–467. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berwick D. Looking forward: the NHS: feeling well and thriving at 75. BMJ. 1998;317:57–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berwick DM. Continuous improvement as an ideal in health care. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:53–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901053200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walshe K. Opportunities for improving the practice of clinical audit. Q Health Care. 1995;4:231–232. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.4.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards KF. Developments in total quality management in the United States: the intermountain health care perspective. Q Health Care. 1994;3(suppl):20–24. doi: 10.1136/qshc.3.suppl.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scherkenbach WW. Washington, DC: George Washington University; 1986. The Deming route to quality and productivity: road maps and roadblocks. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.