Abstract

Hepadnaviruses are DNA viruses but, as pararetroviruses, their morphogenesis initiates with the encapsidation of an RNA pregenome, and these viruses have therefore evolved mechanisms to exclude nucleocapsids that contain incompletely matured genomes from participating in budding and secretion. We provide here evidence that binding of hepadnavirus core particles from the cytosol to their target membranes is a distinct step in morphogenesis, discriminating among different populations of intracellular capsids. Using the duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) and a flotation assay, we found about half of the intracellular capsids to be membrane associated due to an intrinsic membrane-binding affinity. In contrast to free cytosolic capsids, this subpopulation contained largely mature, double-stranded DNA genomes and lacked core protein hyperphosphorylation, both features characteristic for secreted virions. Against expectation, however, the selective membrane attachment observed did not require the presence of the large DHBV envelope protein, which has been considered to be crucial for nucleocapsid-membrane interaction. Furthermore, removal of surface-exposed phosphate residues from nonfloating capsids by itself did not suffice to confer membrane affinity and, finally, hyperphosphorylation was absent from nonenveloped nucleocapsids that were released from DHBV-transfected cells. Collectively, these observations argue for a model in which nucleocapsid maturation, involving the viral genome, capsid structure, and capsid dephosphorylation, leads to the exposure of a membrane-binding signal as a step crucial for selecting the matured nucleocapsid to be incorporated into the capsid-independent budding of virus particles.

Enveloped viruses acquire their outer coat by budding at cellular membranes, a step generally thought to depend on the interaction between the viral envelope proteins and internal viral matrix and nucleocapsid components (7). However, some viruses, such as retroviruses and rhabdoviruses, are able to release membrane-coated particles also in the absence of viral envelope proteins (5, 9, 23). Moreover, other viruses, including coronavirus, herpes simplex virus type 1 and, in particular, the hepadnaviruses, release empty envelope particles devoid of nucleocapsids, in addition to infectious virus (28, 30). Hepatitis B viruses (HBVs; hepadnaviruses) are small, enveloped viruses and a causative agent of acute and chronic viral hepatitis (6). Their nucleocapsid, or core particle, which is composed of a single core protein species, contains a largely double-stranded DNA genome and the covalently attached viral polymerase and is surrounded by a membrane shell with two or three viral envelope proteins embedded. In addition to these infectious virus particles, hepadnavirus-infected cells secrete, in abundant excess, nucleocapsid-free enveloped particles, suggesting that hepadnavirus budding may be an envelope protein-driven process. On the other hand, it has been shown that budding and secretion of complete virus particles require the presence of the large viral envelope protein (L-protein) (2, 27). This has led to the assumption that nucleocapsids enter the export pathway by attaching to cytosolically exposed preS ectodomains of membrane-anchored L chains at the ERGIC (endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi intermediate compartment) into which they bud (11, 19).

Hepadnaviruses replicate their genome via reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate, a process occurring already in the producer cell and thereby differing from the related retroviral life cycle (17, 25). Intracellular core particles thus contain the viral genome at various stages of maturation, while secreted virus has been found to contain only the mature replication end product, a largely double-stranded DNA molecule. These observations have been taken to indicate that completion of genome replication is a prerequisite for capsid envelopment, and they predict that core particles containing a mature viral DNA genome display signals for selective budding and export (25). Support for this prediction comes from more recent experiments demonstrating a block to virus production for capsids unable to complete DNA synthesis due to mutational inactivation of the viral polymerase (8, 31). While this model has been generally accepted, the nature of the predicted maturation signal and its cellular or viral interaction partner(s) have remained unknown, as has the mechanism resulting in selective export of mature capsids. However, it has been extrapolated that genome maturation could lead to the exposure of L-protein binding sites on the particle surface, involving changes in the overall nucleocapsid structure (25, 31). Alternatively, or additionally, more-subtle changes have been considered to signal capsid maturation, such as a change in core protein hyperphosphorylation (characterized by the complex series of core protein species detected upon sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis ([SDS-PAGE]) that is typically observed with intracellular capsids but is absent in the secreted virion (21, 22).

We addressed the issues of how hepadnavirus nucleocapsids are selected for secretion using duck HBV (DHBV) and an adapted flotation assay that had been previously used to study other viral systems (1, 5). The data we obtained indicate that (i) an initial selection of mature nucleocapsids by membrane attachment does not require an interaction with the large envelope protein and, furthermore, that (ii) extensive dephosphorylation of capsid protein subunits, although correlating with membrane attachment, is by itself not sufficient to confer membrane affinity to free cytosolic nucleocapsids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus, plasmids, and antibodies.

DHBV subtype 16 (15) was used throughout the study. pD1.3 contains 1.3 copies of the DHBV 16 genome in tandem arrangement (starting and terminating at genome positions 1847 and 2816, respectively) inserted into a minimal pUC vector for bacterial amplification. Plasmid pD1.3 L(−) bears a G-to-A mutation at nucleotide position 1165 leading to a stop codon in the preS open reading frame at amino acid (aa) 122. A polyclonal rabbit serum raised against DHBV core protein purified from infected duck liver (D087) was used as the primary antibody in Western blot analysis.

Cell culture and transfection.

DHBV-positive livers were obtained from 4- to 6-week-old ducks, infected congenitally or experimentally. Primary duck hepatocytes (PDHs) were prepared and cultivated as described previously (10). For transfection experiments, the LMH cells (13) were seeded into a six-well culture dish (about 5 × 105 cells) 24 h before transfection. To prepare the calcium phosphate precipitate, 20 μg of plasmid DNA was ethanol precipitated and dissolved in 500 μl of 0.25 M CaCl2. After the addition of 500 μl of 2× HBS (280 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM Na2HPO4; pH 7.1), samples were incubated for 20 min at room temperature and 100 μl of the sample was added dropwise into the medium. At 16 h posttransfection, cells were washed and fresh medium was added. After 5 days, cells were harvested as described below.

DHBV density flotation assay.

DHBV-infected PDHs or transfected LMH cells were harvested 5 days after plating or transfection, respectively, and fractionated essentially as described previously (1), with some modifications: plates were first rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and then scraped into ice-cold 10% (wt/wt) sucrose homogenization buffer containing 10 mM Tris hydrochloride (Tris-HCl; pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, and 100 U of kallikrein/ml of aprotinin. PDHs, transfected LMH cells, or infected liver were disrupted on ice with 60 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. Nuclei and debris were removed from the cell lysate by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm at 4°C for 4 min. The resulting postnuclear supernatant was made to 60% (wt/wt) sucrose, placed at the bottom of a Beckman SW60 centrifuge tube, and overlaid with 48% (2 ml) and 10% (1 ml) sucrose. The step gradient was then centrifuged at 40,000 rpm at 20°C for 3 h (or occasionally at 4°C for 16 h, no difference in the results being observed). Fractions were collected from the top. The membrane fraction, corresponding to the 10 to 48% sucrose interface, and the cytosolic fraction, corresponding to the 60% sucrose fraction at the bottom of the gradient, were analyzed for DHBV DNA or were trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitated and analyzed for DHBV core protein. Total nucleic acids were extracted from membrane or cytosolic fractions as described previously (26). Membrane and cytosolic fraction were digested by addition of 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, and 0.5 mg of pronase/ml) at 37°C for 1 h. The digested lysate was extracted one time with each an equal volume of phenol and chloroform, and nucleic acids were precipitated by the addition of 2 volumes of absolute ethanol. After precipitation nucleic acids were pelleted by centrifugation, washed once with ethanol 70% (vol/vol), dried, dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA), and analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting.

For refloating of nucleocapsids, membrane and cytosolic capsids isolated from a first density flotation assay were released from membranes overnight at 4°C by the addition of 1% NP-40. To remove the detergents, the capsids were pelleted in an TLA45 (1 h, 44,000 × g, 20°C), and the resulting pellet was washed twice in homogenization buffer and resuspended by shaking overnight at 4°C in homogenization buffer. After a low-speed centrifugation, the supernatant containing the resuspended capsids was then mixed with membranes from a noninfected duck liver collected from the membrane fraction of another density flotation, and the mixture was adjusted to 60% (wt/wt) sucrose and subjected to another density flotation.

Analysis of cell culture supernatants.

To determine the yield of enveloped virions versus nonenveloped core particles secreted from transfected cells, 1 ml of the supernatant was centrifuged into a CsCl step gradient (1.5, 1.4, and 1.3 g/ml, overlaid with 20% sucrose), and DHBV DNA in each fraction was quantified relative to a standard by dot blot hybridization as described previously (18). The proteins present in the cell supernatant or in membrane and cytosolic fractions were TCA precipitated (10% final) for 30 min. After centrifugation (10 min at 13,000 rpm), the pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of sample buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.8], 10% sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 3% SDS, 2% β-mercaptoethanol). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% acrylamide) and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) using a Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% skim milk in TBST (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 0.3% Tween 20). Membranes were probed with a polyclonal anti-core antiserum (D087) for 2 h in 5% skim milk–TBST, washed three times (10 min each time) with TBST, and probed with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) in 5% skim milk–TBST for 1 h. After three 10-min washes in TBST, protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's manual. For quantification of the signals, the secondary antibody was alkaline phosphatase conjugated, and enhanced chemifluoresence (ECF; Amersham) was performed with a Fluoroimager (Molecular Dynamics) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Dephosphorylation of the core particles.

Prior to refloating, purified membrane-associated and cytosolic capsids were dephosphorylated by alkaline phosphatase treatment as described previously (21). In brief, the capsids were incubated with alkaline phosphatase (4 U/ml; type III from Escherichia coli; Sigma) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–5 mM dithiothreitol–10 mM MgCl2–100 mM Na2SO4 for 18 h at 25°C. Protease inhibitors were added as CLAP cocktail (Boehringer Mannheim). The capsids were pelleted and resuspended in the homogenization buffer as described above.

RESULTS

A large fraction of intracellular core particles have the intrinsic property to bind to cellular membranes.

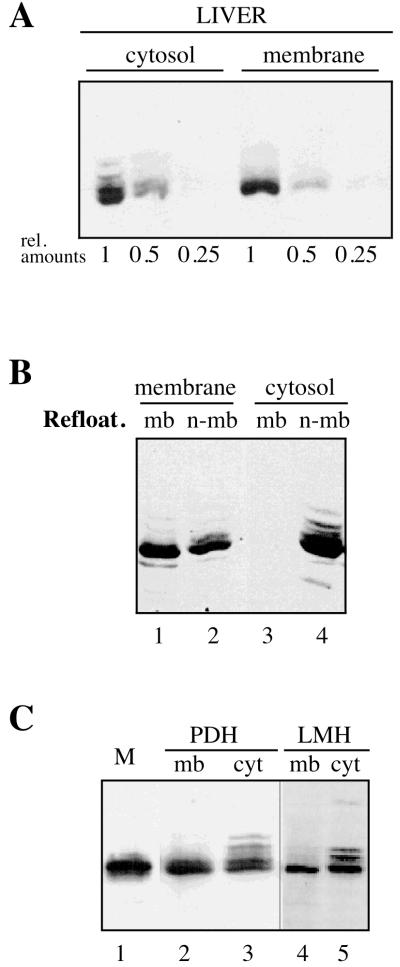

Membrane-associated DHBV capsids were detected and isolated using a flotation assay in which cellular homogenates were subjected to density centrifugation into an overlaid sucrose step gradient (see Materials and Methods). In this assay system, membrane-bound viral proteins are comigrating with membranes to the 10 to 48% sucrose interface and separated from free, cytosolic components which remain at the bottom of the centrifuge tube. When material from DHBV-infected duck liver was subjected to this procedure, a large fraction of the DHBV core protein was detected in the membrane fraction. The amounts of core protein in both membrane and bottom (cytosolic) fraction were compared by Western blotting of dilution series and found to be about equal (Fig. 1A). Since the core protein from either fraction was pelletable by ultracentrifugation in the presence of detergent (see below), these results indicate that about half of the intracellular core particles are associated with cellular membranes in the liver of a DHBV-infected duck.

FIG. 1.

A large fraction of intracellular DHBV core particles binds to cellular membranes, due to an intrinsic membrane affinity. (A) About half of the core particles are membrane associated. Duck liver homogenates from infected animals, depleted of the nuclear fraction, were subjected to density flotation as described in Materials and Methods. The resulting membrane and cytosolic fractions were analyzed by Western blot for the presence of DHBV core protein. Lanes 1, 0.5, and 0.25 represent a dilution series used to estimate relative protein concentrations. (B) Core particles from the membrane fraction rebind to cellular membranes. Membrane (membrane) and cytosolic (cytosol) fractions from a floating experiment as described in panel A were treated with detergent, and the contained core particles were pelleted, washed, subjected to refloating with membranes from noninfected duck hepatocytes, and detected by Western blotting in the resulting membrane-bound and nonbound fractions (mb, lanes 1 and 3; n-mb, lanes 2 and 4, respectively). (C) Membrane-associated capsids lack core protein hyperphosphorylation characteristic for intracellular nucleocapsids. A western blot detecting the DHBV core protein in membrane or cytosolic fractions (mb, lanes 2 and 4; cyt, lanes 3 and 5, respectively) from DHBV-infected PDHs or from LMH cells transfected with pD1.3 (LMH) is shown. Recombinant DHBV core protein from E. coli was included as a marker for the nonphosphorylated protein species (M, lane 1).

To confirm the specificity of the observed membrane binding, capsids from the membrane fraction were liberated from membranes by treatment with 1% NP-40, pelleted by ultracentrifugation, mixed with native (DHBV-free) cellular membranes, and retested in the flotation assay for the persistence of their membrane-binding capacity (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2). After such treatment, a major fraction of the capsids that had initially floated with cellular membranes was found to be able to reassociate with the newly added membranes (about 50% in the experiment shown in Fig. 1B and 90% in another experiment [not shown]). As a control, capsids from the bottom fraction of the initial separation, representing free cytosolic particles that had been treated identically, again did not show any membrane affinity (Fig. 1B, lanes 3 and 4). From these data, we conclude that the membrane-bound capsids represent a distinct subpopulation differing from cytosolic core particles by possessing an intrinsic membrane affinity. Moreover, the observation of efficient rebinding with membranes from noninfected duck liver suggests that the membrane binding observed may not necessarily depend on the presence of the membrane-embedded viral envelope proteins.

Membrane-associated capsids lack core protein hyperphosphorylation.

In the initial Western blots analyzing the distribution of intracellular capsids (Fig. 1A and B), a characteristic difference was observed with respect to the number of core protein bands resolved and detected. In SDS-PAGE, intracellular DHBV core protein molecules are known to display a complex mobility pattern, related to the variable extent of phosphorylation at least four distinct serine and threonine residues in their C-terminal portion (22, 32). In membrane-bound capsids, the several slower-migrating bands representing the various phosphorylated protein species were much reduced or absent (Fig. 1A), a result indicating that the great majority of core protein subunits were not phosphorylated at sites affecting their electrophoretic mobility. In contrast, core protein from cytosolic capsids showed the heterogeneous pattern characteristic of the mixture of hyperphosphorylated intracellular core gene products.

These initial observations with material from duck liver were confirmed in experiments analyzing capsids from either DHBV-infected PDHs or from LMH cells that had been productively transfected with a plasmid (pD 1.3) carrying a replication-competent DHBV genome (Fig. 1C). In these experimental systems, hyperphosphorylated core protein subunits were produced in higher proportions than in DHBV-infected liver. Again about half of the intracellular core protein was detected as either membrane bound (mb, lanes 2 and 4) or free in the cytosolic fraction (cyt, lanes 3 and 5), respectively. As already observed in Western blots of cell extracts from duck liver, only the fastest-migrating core protein band was detected in the membrane fraction (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 4), comigrating with nonphosphorylated, recombinant DHBV core protein produced from E. coli (Fig. 1C, lane M). In contrast, the slower-migrating, hyperphosphorylated species were selectively enriched among the free cytosolic capsids (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 5). Similar results were observed when the analysis was performed in a phosphate buffer to inhibit a potential removal of phosphate residues by cellular phosphatases present in the crude cell extracts used (data not shown). Based on data from three different experimental systems used, we deduce that the membrane-associated capsids represent a distinct subpopulation of intracellular capsids that are characterized by a much-reduced level of core protein phosphorylation.

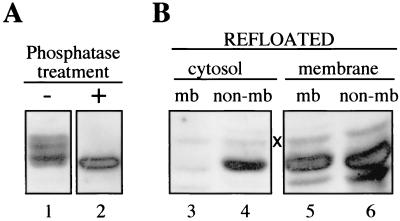

Core protein dephosphorylation is not sufficient to induce the membrane binding of capsids.

The data presented so far would be compatible with a model in which surface-exposed phosphate residues are used as a signal on the capsid surface to trigger membrane attachment of core particles. This hypothesis was challenged by testing whether cytosolic phosphorylated core particles would gain membrane affinity after enzymatic removal of surface-exposed phosphate residues. As shown in Fig. 2 and as described previously (21), treatment of cytosolic capsids with phosphatase resulted in a complete disappearance of the slowly migrating bands of core protein, indicating extensive capsid dephosphorylation (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2). However, such modified capsids were still unable to bind to membranes (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). In a parallel control experiment, phosphatase pretreatment did not interfere with the rebinding of membrane-derived nucleocapsids to liver membranes (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 6), excluding two counteracting effects of the phosphatase treatment. In this experiment, a minor, slower-migrating band was additionally detected in the Western blot shown (marked “×” in Fig. 2B). However, since it is present in comparable strength in membrane-rebound and nonbound fractions and also irrespective of the initial fractionation, this signal of unknown origin appears to be irrelevant for the above interpretation of the data.

FIG. 2.

Core protein dephosphorylation alone does not confer membrane affinity to free cytosolic nucleocapsids. A western blot detecting the DHBV core protein of free cytosolic capsids from infected duck liver, before and after phosphatase treatment (−, lane 1; +, lane 2), is shown. After floating with added cellular membranes, the resulting membrane fractions (mb, lanes 3 and 5) and nonbound fractions (non-mb, lanes 4 and 6) were analyzed for core protein again by Western blotting. The minor signal marked “×” is of unknown origin and is unrelated to the subpopulations of nucleocapsids separated by refloating.

Thus, while the dephosphorylation of the core protein may be important at some other stages of the envelopment process, this modification of the core particle appears to be not sufficient to confer the ability to bind to cellular membranes. Notably, this conclusion is also valid for possibly existing surface-exposed phosphate residues not causing a mobility shift in PAGE and therefore escaping detection in our analysis.

Membrane association of core particles does not require the presence of the large viral envelope protein.

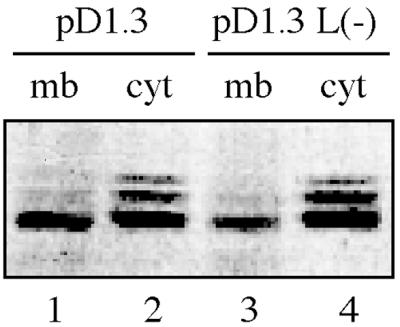

The results of the refloating experiment with cellular membranes from noninfected duck liver (Fig. 1B) had already raised doubts as to whether the membrane binding of core particles depended upon the presence of the L-protein. To further explore this issue, we assayed for membrane association of capsids that were produced from a DHBV genome carrying a stop codon at aa 122 in the preS-coding sequence. This construct, pD 1.3 L(−), is unable to produce L-protein and, furthermore, immunoblot studies showed that it did not produce any detectable amounts (<2 to 5% of a wild-type L control) of the 121-aa preS fragment predicted to be produced and potentially functioning in the preS-mediated membrane association of capsids (B. Zachmann-Brand and H. Schaller, unpublished data). Capsids produced in LMH cells transfected with this construct were still found to be membrane associated (Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4), although to somewhat reduced levels (ca. 30%) compared to the wild-type control (ca. 50%, Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2), as revealed by ECF quantification. Furthermore, there was the same correlation between membrane association and the much-reduced core protein hyperphosphorylation as observed for wild-type DHBV (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 3, respectively).

FIG. 3.

Membrane association of core particles does not require the presence of the large DHBV envelope protein. A western blot detecting the DHBV core protein in membrane (mb, lanes 1 and 3) and the cytosolic fractions (cyt, lanes 2 and 4) from LMH cells transfected with pD1.3 or transfected with a DHBV genome incapable of synthesizing the large DHBV envelope protein [pD1.3 L(−)] is shown.

These results further support the data from the above-described refloating experiment, collectively indicating that a selected fraction of nucleocapsids associates specifically with cellular membranes even in the absence of interaction with the L-protein at the target membrane. The distinct reduction of membrane-bound capsids reproducibly observed in case of the DHBV L(−)-transfected cells implies, however, that the L-protein may nonetheless contribute the core particle-membrane interaction.

Nonenveloped virus particles released from DHBV-transfected cells are related to intracellular, membrane-bound nucleocapsids.

There have been many reports describing, but not further investigating, the release of apparently “naked” core particles from hepatoma cell lines that had been transfected with replication-competent HBV or DHBV genomes. These particles were characterized as nonenveloped by their sensitivity to protease digestion and their increased buoyant density in cesium chloride density gradients (12, 14, 24), as well as by their ability to incorporate radiolabeled deoxyribonucleotides in the absence of detergents (Zachmann-Brand and Schaller, unpublished). It has been generally assumed that production of these naked capsids was a result of cell lysis; however, a release by an unknown secretion pathway had not been ruled out (17).

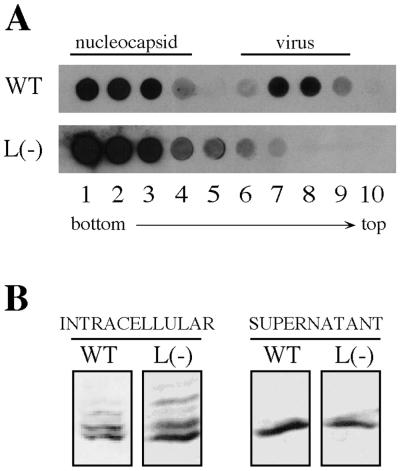

To study a possible correlation of this unconventional process to the membrane association of intracellular hepadnaviral capsids, LMH cells were transfected with DHBV-expressing plasmid pD 1.3 or with the corresponding L(−) mutant plasmid. Figure 4A shows the DNA dot blot analysis of cesium chloride density gradients analyzing the cell culture supernatants at day 4 posttransfection. As mentioned above, cells transfected with DHBV wild-type genomes produced enveloped virus particles (banding in fractions 7 and 8), as well as naked nucleocapsids banding at the higher density (fractions 1 to 3); in the case of the L-stop construct, naked (DNA-containing) particles were produced in larger amounts (up to a five-fold increase, compared to wild type) and were the only product.

FIG. 4.

Nonenveloped virus particles released from transfected cells into the culture medium display the dephosphorylated core protein pattern characteristic for membrane-bound intracellular nucleocapsids and secreted virus. LMH cells were transfected with pD1.3 wild type (WT) or pD1.3 L(−) [L(−)] and cultivated for further 4 days. (A) A portion (1 ml) of cell culture medium was subjected to centrifugation in a preformed cesium chloride density gradient. Fractions collected were analyzed by a DHBV-specific DNA dot blot. (B) Western blot analysis of DHBV core protein in total cell lysates (intracellular) or in enveloped and nonenveloped virus particles pelleted from the cell culture medium (supernatant).

To determine the phosphorylation state of these nonenveloped capsids, particles were pelleted from each cell culture supernatant and tested in a Western blot for the electrophoretic mobility pattern of the contained DHBV core protein species (Fig. 4B). For comparison, we also included intracellular capsids from total cell extracts of each transfection. As shown above, these intracellular core particles displayed a heterogeneous mobility in SDS-PAGE analyses, indicating extensive and variable phosphorylation of the core protein subunits. In contrast, the core protein molecules from extracellular particles were migrating as a single band, demonstrating a phosphorylation state similar to that observed above with the membrane-associated intracellular capsids (Fig. 1 and 3). Taking core protein phosphorylation as an indicator, we find that released nucleocapsids resemble the membrane-bound subfraction of intracellular core particles, not only in the case of secreted virus (21) but also in case of liberated nonenveloped nucleocapsids. This result lends strong support to the notion that release of naked core particles reflects a secretion mechanism that is preceded by the selective membrane attachment of mature capsids characteristic of virus budding.

Membrane binding selects for core particles containing mature genomes.

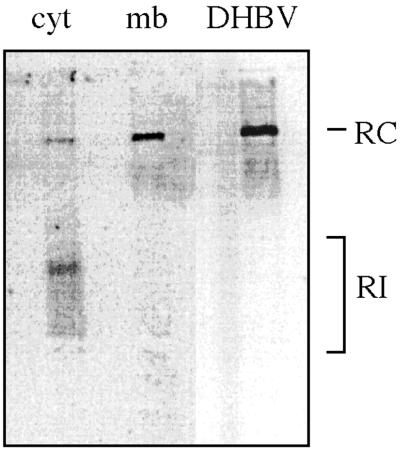

Another hallmark of secreted hepadnaviruses is that their nucleocapsids contain the mature, largely double-stranded DNA genome, whereas all stages of genome maturation can be found in intracellular capsids (25). Since membrane-bound nucleocapsids resembled those of secreted virus with regard to the phosphorylation state of their protein subunits, we wanted to assess whether they also contain a matured viral genome. Membrane-bound and free cytosolic particles were examined for the maturation state of the encapsidated viral nucleic acid by Southern blot analysis following the floating separation procedure (Fig. 5). In capsids associated with the membrane fraction of homogenates from infected duck liver, only the mature, relaxed circular form (RC) of the DHBV genome was detectable, as characterized by comigration with a DHBV DNA from serum virions. In contrast, preparations of free cytosolic nucleocapsids displayed a pattern indicative of the presence of the faster-migrating, immature replicative intermediates (RI). Similar results were obtained with capsids from cultured duck hepatocytes derived from DHBV-infected animals (data not shown). The quantification of the radioactive signals in the PhosphorImager showed that in both cases the great majority of the RC DNA genomes were present in the membrane fraction (ca. 90%), confirming a strong enrichment for mature nucleocapsids at cellular membranes. Thus, a mature viral genome and dephosphorylated capsid protein subunits, two characteristics of secreted virus, are already present at the stage of membrane association.

FIG. 5.

Membrane binding selects for nucleocapsids containing a mature DNA genome. A liver homogenate from a DHBV-infected duck was subjected to flotation centrifugation (as described in Fig. 1A), and equal amounts of core particles from either the cytosolic or the membrane fraction were analyzed for DHBV DNA by Southern blotting. Serum-derived virus DNA was loaded as a control (DHBV). RC, relaxed circular form; RI, replicative intermediates.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals a novel aspect in hepadnaviral morphogenesis by identifying an intrinsic membrane-binding affinity as a characteristic property of a distinct subpopulation of intracellular core particles, which seemingly represents those destined to be enveloped and secreted. In contrast to the free cytosolic species, membrane-bound nucleocapsids were found to lack core protein hyperphosphorylation and to contain the mature form of the viral DNA genome, thus resembling the nucleocapsid as present in secreted virus particle.

Since the large envelope protein has been indicated to be essential for virion formation and secretion of hepadnaviruses (2, 27), the assumption prevails that the matured nucleocapsid is recognized by and bound to L chains at the membrane of the cellular compartment into which it buds, i.e., the ERGIC (11, 19). However, by demonstrating that cellular membranes maintain their selective affinity for matured capsids in the absence of L, our data are incompatible with such a simple model. Instead, we conclude that the mature capsid interacts at the target membrane primarily with nonviral components, such as phospholipids or cellular membrane proteins, which we expect to be enriched in the compartment where hepadnavirus budding is initiated. The L-protein seems nonetheless to be needed to direct membrane-bound nucleocapsids to the budding membrane structures formed by the sole interaction of viral envelope proteins, independent of capsid attachment. Accordingly, our finding that the fraction of membrane-associated nucleocapsids was reduced in the absence of L suggests that the L-protein contributes to the stability of membrane-capsid binding, in keeping with the notion of a capsid-L interaction constituting a matrix-like function (3). A general significance of these data from DHBV for hepadnaviral morphogenesis is further supported by results from initial cofloating experiments with HBV core particles and mouse liver microsomes in which half of the nucleocapsids was found to membrane associate, without any major contribution of HBV L-protein (our unpublished data).

In an attempt to elucidate the function of dephosphorylation of the DHBV core protein during morphogenesis, Yu and Summers examined in detail the phenotypes of mutants substituting serine and threonine at positions 239, 245, 257, or 259 (33). In that study, only small reductions in virus production compared to wild type (maximally two-fold with the S257 mutant or the S259 mutant) were noted, suggesting that core protein phosphorylation-dephosphorylation at these sites does not play a crucial role in the envelopment process (33; W. Yu and J. Summers, personal comm.). However, since only single amino acid changes were investigated, these data did not rule out more-stringent effects of phosphorylation at multiple sites. As to the nature of the signal for membrane binding eventually presented on the surface of capsids, particle dephosphorylation by itself appears not to be the structural feature selecting mature particles, since removal of exposed phosphate residues was not sufficient to confer membrane affinity to cytosolic nucleocapsids. Nevertheless, by correlating with membrane association, particle dephosphorylation may function as an auxiliary element, contributing to the features recognized by the target membrane.

The unconventional mechanism of membrane targeting of the hepadnavirus nucleocapsids discussed above is also in keeping with the rather efficient secretion of nonenveloped core particles from transfected cells. Although already mentioned in the initial reports describing hepadnavirus production from cells transfected with DNA genomes (12, 24), this process has been generally ignored, since it has been assumed that these capsids may solely originate from lysed cells (17). However, our present finding that these unconventionally liberated naked core particles display the same characteristic dephosphorylation of membrane-bound nucleocapsids (and capsids in secreted virions) strongly argues that these particles originate from the very same membrane-bound subpool of matured capsids that is normally secreted as enveloped virus and thus suggests that capsid secretion without envelope is initiated by membrane binding. Importantly, envelope-free, extracellular hepadnavirus particles are produced only from transfected cells, but are not found in infected hepatocyte cultures or test animals (unpublished observations) or in immunocompromised HBV patients (20). This correlation suggests that secretion of hepadnavirus particles without envelope results from an unbalanced nucleocapsid overproduction in transfected cells, particularly as was done here, if large amounts of intracellular core particles are produced from constructs using a strong heterologous promoter to direct synthesis of the pregenomic RNA and/or in the absence of the large envelope protein.

Secretion of nucleocapsids devoid of envelope proteins has been reported for several other viruses such as rhabdoviruses (16, 23) or retroviruses (5, 9). However, in contrast to the naked hepadnavirus capsids released, the secreted nucleocapsids were found to be fully enveloped by cell surface membranes. It seems likely that this difference reflects the different driving forces for the budding process, which may be attributed in these viruses to their matrix components, whereas hepadnavirus budding appears to be driven by the envelope components alone (19). Thus, the secretion of nucleocapsids without membrane envelope described here appears to be a very special variation of virus particle release, illustrated elsewhere only by the release of poliovirus prior or in absence of lysis (29).

Collectively, our data refine a model of virus secretion wherein maturation of viral genomes proceeds in cytosolic capsids which are initially phosphorylated and incapable of binding to cellular membranes. A change in the capsid structure, induced by genome maturation, triggers membrane association, preceded or followed by core protein dephosphorylation. If present, the large envelope protein then interacts with membrane-bound capsids, incorporating these into preexisting, envelope-driven budding structures, thus leading to the formation and secretion of enveloped virions along with the vast excess of empty enveloped particles produced independent of capsid attachment. In the absence of L-protein, matured capsids appear to be exported without envelope by an alternative, yet-uncharacterized mechanism or else move to the nucleus to serve for genome amplification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bärbel Glass for the preparation of the PDHs and for providing liver tissue and duck sera, Christa Kuhn for antibodies, Beate Zachmann-Brand for providing the D 1.3 constructs, Marc Hild for helpful discussions, Klaus Breiner for constructive criticism of the manuscript, and Karin Coutinho for expert editorial assistance.

This work was supported by fellowships to H.M. from the Institut National de la Recherche Medicale (INSERM) and the Association Francaise pour la Recherche Therapeutique (AFRT), as well as by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 229) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCE

- 1.Bergmann J E, Fusco P J. The M protein of vesicular stomatitis virus associates specifically with the basolateral membranes of polarized epithelial cells independently of the G protein. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1707–1715. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruss V, Ganem D. The role of envelope proteins in hepatitis B virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1059–1063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruss V, Vieluf K. Functions of the internal Pre-S domain of the large surface protein in hepatitis B virus particle morphogenesis. J Virol. 1995;69:6652–6657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6652-6657.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chong L D, Rose J K. Membrane association of functional vesicular stomatitis virus matrix protein in vivo. J Virol. 1993;67:407–414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.407-414.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delchambre M, Gheysen D, Thines D, Thiriart C, Jacobs E, Verdin E, Horth M, Burny A, Bex F. The GAG precursor of simian immunodeficiency virus assembles into virus-like particles. EMBO J. 1989;8:2653–2660. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganem D. Hepadnaviridae. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2703–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garoff H, Hewson R, Opstelten D J. Virus maturation by budding. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1171–1190. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1171-1190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerelsaikhan T, Tavis J E, Bruss V. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid envelopment does not occur without genomic DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1996;70:4269–4274. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4269-4274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gheysen D, Jacobs E, de Foresta F, Thiriart C, Francotee M, Thines D, de Wille M. Assembly and release of HIV-1 precursor pr55gag virus-like particles from recombinant bacculovirus-infected cells. Cell. 1989;59:103–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90873-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hild M, Weber O, Schaller H. Glucagon treatment interferes with an early step of duck hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:2600–2606. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2600-2606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huovila A P, Eder A M, Fuller S D. Hepatitis B surface antigen assembles in a post-ER, pre-Golgi compartment. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:1305–1320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.6.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Junker M, Galle P, Schaller H. Expression and replication of the hepatitis B virus genome under foreign promoter control. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:10117–10131. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.24.10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi T, Nomurak K, Hirayama Y, Kitagawa T. Establishment and characterization of a chicken hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, LMH. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4460–4464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenhoff R J, Summers J. Coordinate regulation and virus assembly by the large envelope protein of an avian hepadnavirus. J Virol. 1994;68:4565–4571. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4565-4571.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandart E, Kay A, Galibert F. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned duck hepatitis B virus genome: comparison with woodchuck and human hepatitis B virus sequences. J Virol. 1984;49:782–792. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.3.782-792.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mebatsion T, Konig M, Conzelmann K-K. Budding of rabies virus particles in the absence of the spike glycoprotein. Cell. 1996;84:941–951. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nassal M. Hepatitis B virus morphogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:297–337. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obert S, Zachmann Brand B, Deindl E, Tucker W, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. A spliced hepadnavirus RNA that is essential for virus replication. EMBO J. 1996;15:2565–2574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patzer E J, Nakamura G R, Simonsen C C, Levinson A D, Brands R. Intracellular assembly and packaging of hepatitis B surface antigen particles occur in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1986;58:884–892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.3.884-892.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Possehl C, Repp R, Heermann K H, Korec E, Uy A, Gerlich W H. Absence of free core antigen in anti-HBc negative viremic hepatitis B carriers. Arch Virol Suppl. 1992;4:39–41. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-5633-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pugh J, Zweidler A, Summers J. Characterization of the major duck hepatitis B virus core particle protein. J Virol. 1989;63:1371–1376. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1371-1376.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlicht H J, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. The duck hepatitis B virus core protein contains a highly phosphorylated C terminus that is essential for replication but not for RNA packaging. J Virol. 1989;63:2995–3000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2995-3000.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnell M, Mebatsion T, Conzelmann K K. Infectious rabies viruses from cloned cDNA. EMBO J. 1994;13:4195–4203. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sells M A, Chen M L, Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in HepG2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1005–1009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summers J, Mason W S. Replication of the genome of hepatitis B-like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell. 1982;29:403–415. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summers J, Smith P, Horwich A L. Hepadnaviral envelope proteins regulate amplification of covalently closed circular DNA. J Virol. 1990;64:2819–2824. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2819-2824.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Summers J, Smith P M, Huang M J, Yu M S. Morphogenetic and regulatory effects of mutations in the envelope protein of an avian hepadnavirus. J Virol. 1991;65:1310–1317. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1310-1317.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szilagyi J F, Cunningham C. Identification and characterization of a novel non-infectious herpes simplex virus-related particle. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:661–668. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-3-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker S P, Thornton C L, Wimmer E, Compans R W. Vectorial release of poliovirus from polarized human intestinal epithelial cells. J Virol. 1993;67:4274–4282. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4274-4282.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vennema H, Godeke G J, Rossen J W A, Voorhout W F, Horzinek M C, Opstelten D J E, Rottier P J M. Nucleocapsid-independent assembly of coronavirus-like particles by co-expression of viral envelope protein genes. EMBO J. 1996;15:2020–2028. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei Y, Tavis J E, Ganem D. Relationship between viral DNA synthesis and virion envelopment in hepatitis B viruses. J Virol. 1996;70:6455–6458. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6455-6458.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu M, Summers J. Phosphorylation of the duck hepatitis B virus capsid protein associated with conformational changes in the C terminus. J Virol. 1994;68:2965–2969. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2965-2969.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu M, Summers J. Multiple functions of capsid protein phosphorylation in duck hepatitis B virus replication. J Virol. 1994;68:4341–4348. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4341-4348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]