In every country, to a greater or lesser extent, violence blights lives and undermines health. Acknowledging this, in 1996 the 49th World Health Assembly adopted a resolution (WHA49.25) declaring violence a major and growing public health problem across the world. The resolution ended by calling for a plan of action for progress towards a science based public health approach to preventing violence. The World Health Organization defines violence as the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or a group or community, that either results in, or has a high likelihood of resulting in, injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.1 In 2000, an estimated 1.6 million people died as a result of violence. Many more suffered injury. Of the deaths, nearly half were suicides, almost a third were homicides—of whom 57 000 were of children—and about a fifth were related to war. This week, the WHO published the World Report on Violence and Health.2 The report includes sections on youth violence, child abuse, violence by intimate partners, abuse of elderly people, sexual violence, self directed violence, and collective violence. Underlying the bleak statistics in each chapter is a terrifying amount of pain and suffering.

Bringing all forms of intentional violence together in one volume makes very clear how much the different forms of violence feed on each other. People who were subjected to child abuse or violence from an intimate partner are much more likely to harm themselves. Collective violence fractures normal social bonds and often leads to sexual violence and heightened violence in young people. Almost every form of violence predisposes to another. Wherever power is distributed unequally across divisions of socioeconomic class, race, or sex, violence flourishes, and the more unequal the distribution the greater the flourishing. All social classes experience violence, but people with the lowest socioeconomic status are consistently at greatest risk. More than 90% of all violence related deaths occur in low and middle income countries. Inequality always compounds inequality, and, as Wilkinson points out, the distributions of violence and of death from non-violent causes are closely related.3

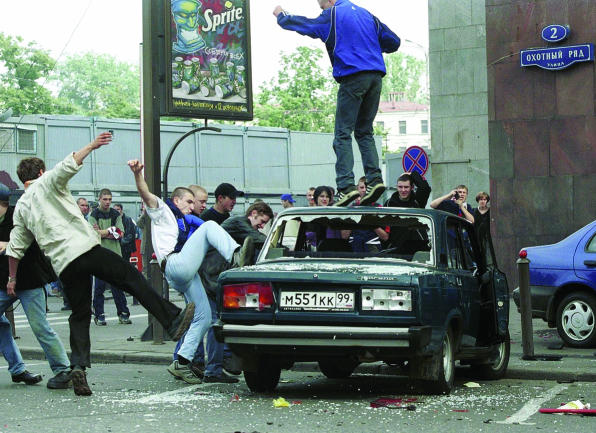

ACTION PRESS/REX

The fundamental premise of the report is that violence is both predictable and preventable. The authors argue that more can be achieved by regarding violence as a problem of public health rather one of crime, and that politicians and decision makers in all countries and at all levels of society have a responsibility to make changes that will prevent violence and so protect health. A science based public health approach has considerable strengths. The painstaking collation of the available statistics from countries across the world allows useful conclusions to be drawn about those factors that seem to make violence more likely. A huge variety of interventions has been tried in different places and the impact evaluated more or less robustly. Public health research already shows that much can be done to minimise violence and that more research is likely to be increasingly useful.

But a public health approach also has its weaknesses. As Skrabanek argues in relation to poverty, violence is unacceptable not primarily because it undermines health but because it is, in itself, demeaning, cruel, and unjust.4 People should be entitled to live free of violence, not because this protects their health but because they have a human right to do so. In important ways, the public health approach diminishes what it is to be human. Human individuals are moral beings whose futures are never entirely determined by their circumstance and who have at least a degree of freedom to make choices about the ways in which they will and will not act. This freedom is the essence of human dignity and, as humans, we judge each other on the basis of these free choices. The existence of choice is captured in the report in the notion of intentionality included in the definition of violence but thereafter receives scant attention. Clearly, it can be much easier to make laudable moral choices when the circumstances of one's life are untroubled by lack of hope and opportunity, but everyone retains a degree of choice, whatever their circumstances. To what extent does an explanation of violence condone it? These issues were well understood by Aristotle and the writers of the Greek tragedies, and the extenuating power of a lack of moral luck has been debated ever since.5 The debate remains as relevant as ever and deserves some consideration by the WHO.

The report's recommendations call on policy makers and governments to integrate prevention of violence into social and educational policies and so promote gender and social equality. What the report does not point out is that governments are dependent on their electorates, who too often resist the allocation of more services and resources to poor families and communities. The unasked question is whether people in all societies who find themselves comfortably situated on the gaining side of inequality and favoured by moral luck will exercise their gift of free choice to support policies that promote the more equal distribution of hope, opportunity, and power. Mann and colleagues argue that the promotion and protection of health are inextricably linked to promotion and protection of human rights and dignity.6 If a human rights perspective were allowed to temper the undoubted strengths of the science based public health approach a much more comprehensive response to the challenge of world violence could be achieved.

News p 731

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global Consultation on Violence and Health. Violence: a public health priority. Geneva: WHO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi A, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson R. Mind the gap. Hierarchies, health and human evolution. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skrabanek P. The death of humane medicine. London: Social Affairs Unit; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nussbaum MC. The fragility of goodness. Luck and ethics in Greek tragedy and philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann JM, Gostin L, Gruskin S, Brennan T, Lazzarini Z, Fineberg HV. Health and human rights. Health Hum Rights. 1994;1:7–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]