Abstract

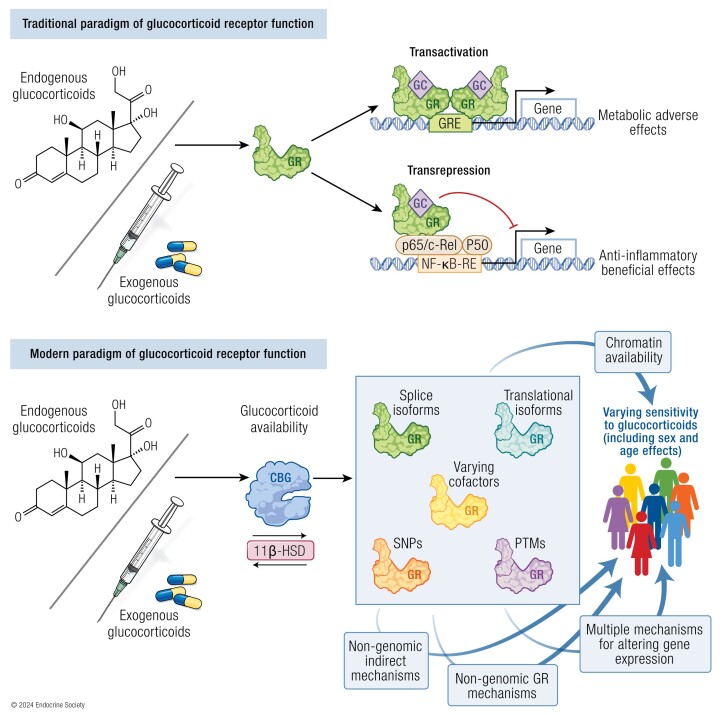

Glucocorticoids exert pleiotropic effects on all tissues to regulate cellular and metabolic homeostasis. Synthetic forms are used therapeutically in a wide range of conditions for their anti-inflammatory benefits, at the cost of dose and duration-dependent side effects. Significant variability occurs between tissues, disease states, and individuals with regard to both the beneficial and deleterious effects. The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is the site of action for these hormones and a vast body of work has been conducted understanding its function. Traditionally, it was thought that the anti-inflammatory benefits of glucocorticoids were mediated by transrepression of pro-inflammatory transcription factors, while the adverse metabolic effects resulted from direct transactivation. This canonical understanding of the GR function has been brought into question over the past 2 decades with advances in the resolution of scientific techniques, and the discovery of multiple isoforms of the receptor present in most tissues. Here we review the structure and function of the GR, the nature of the receptor isoforms, and the contribution of the receptor to glucocorticoid sensitivity, or resistance in health and disease.

Keywords: glucocorticoids, glucocorticoid receptor, glucocorticoid receptor isoforms, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, glucocorticoid sensitivity

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Essential Points.

The glucocorticoid receptor, through expression of isoforms, interaction with cofactors, interaction with DNA and RNA, and interaction with other transcription factors, plays a key role in glucocorticoid sensitivity and tissue-selective action.

The glucocorticoid receptor isoforms diversify glucocorticoid function; a greater understanding of their functions and the role they play in disease is required.

The canonical understanding of glucocorticoid receptor function has been challenged by recent data and is much more complex and varied than previously understood.

Glucocorticoids are 21-carbon corticosteroid hormones derived from cholesterol in the adrenal gland, under control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (1). They exert pleiotropic effects on all tissues to regulate cellular and metabolic homeostasis, including, but not limited to, functions such as the response to stress, inflammation, metabolism, sodium and water balance, and reproductive function (2). In humans, cortisol is the main physiological glucocorticoid, and it acts via binding to the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a member of the highly conserved nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group of intracellular hormone receptors (3). Ligand binding to GR results predominantly in transcriptional regulation, and in some conditions and tissues, glucocorticoids may regulate up to 20% of the genome (4). In recent years, researchers have identified a number of splice and transcription initiation site isoforms of the GR, which allow diversification of glucocorticoid action and, in part, mediate cellular sensitivity to glucocorticoids (3, 5).

Therapeutically, the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive actions of glucocorticoids are harnessed to treat a wide range of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, with synthetic glucocorticoids forming critical components of organ transplantation and chemotherapeutic regimens in addition to hormone replacement in hypocortisolism (6). It was estimated that 1% of the UK population was on chronic glucocorticoid therapy in the 1990s (7); however, more recent data from Denmark suggests the population prevalence was around 3% between 1999 to 2014, increasing with age to up to almost 11% in those over 80 years of age (8). Their immunosuppressive benefits need to be balanced against an extensive, dose-dependent side-effect profile that includes diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, weight gain, myopathy, and osteoporosis, culminating in excess mortality (9-13). Currently, we understand that sensitivity to glucocorticoids (to both beneficial and adverse effects) varies between individuals, yet clinically, we have no way to assess this objectively a priori or to measure glucocorticoid activity upon treatment commencement, and so we are limited to the retrospective review of clinical response, which may expose patients to the risk of harmful side effects or ineffective dosing. The desire to improve the efficacy of glucocorticoids while avoiding the side effects has led to research into the development of selective GR agonists (SEGRAs) which have yet to be successfully translated from preclinical studies (14). A greater understanding of interindividual differences in glucocorticoid sensitivity is expected to elucidate potential biomarkers for assessment/monitoring of patients who require glucocorticoid therapy, thereby improving the safety of treatment. Here we review the recent advances in understanding of the GR and its isoforms, and the role that they play in mediating glucocorticoid sensitivity.

Glucocorticoids and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function

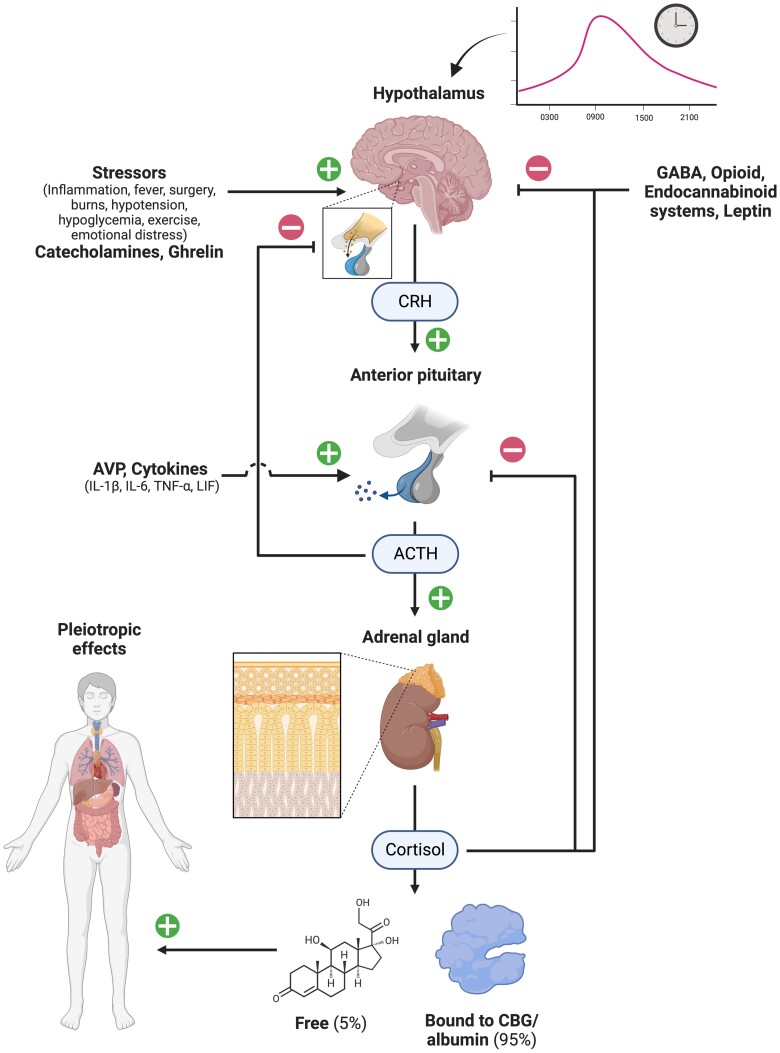

Glucocorticoids are synthesized in the zona fasciculata, the middle of 3 layers of the adrenal cortex, through a series of enzymatic modifications of cholesterol and downstream steroidogenic precursors; in humans, cortisol is the primary glucocorticoid (Fig. 1) (15). This occurs under control of the HPA axis, comprising neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), corticotrope cells of the anterior pituitary, and the aforementioned adrenocortical cells (1). The HPA axis controls both basal cortisol secretion and the response to stress; its function is tightly regulated, including negative feedback loops, and in nonstressed conditions it displays circadian and ultradian rhythmicity.

Figure 1.

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The hypothalamus secretes CRH with a circadian rhythm, which acts on anterior pituitary corticotrope cells, stimulating secretion of ACTH (among other hormones). This induces cortisol secretion from the adrenal gland. Cortisol circulates predominantly bound to CBG and induces pleiotropic effects in almost all tissues. Several external inputs modulate this system and negative feedback loops constrain the secretion at each level, ultimately maintaining normal serum cortisol levels. (+) indicates stimulates; (−) indicates inhibits. Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; AVP, arginine vasopressin; CBG, corticosteroid-binding globulin; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; IL-6, interleukin 6; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α. Created with Biorender.com.

HPA Axis Regulation and Feedback

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is a peptide hormone synthesized predominantly in parvocellular neurons of the PVN, and secreted into the hypophyseal portal vessels which traverse the pituitary stalk and deliver CRH to the anterior pituitary (16, 17). CRH binds to its cognate receptor on anterior pituitary corticotrope cells to stimulate production and secretion of pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) (16, 18). Stimulation of POMC by CRH is potentiated by arginine vasopressin (AVP; also known as anti-diuretic hormone, ADH), another hypothalamic hormone, but can also be enhanced by other hormones, including angiotensin II, cholecystokinin, and atrial natriuretic peptide, among others (19, 20). POMC is a large hormone precursor that is cleaved in a tissue-specific fashion variably into α, β, and γ-melanocyte stimulating hormones, β-endorphin, β and γ-lipoproteins, and importantly for the HPA axis, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (18, 21). ACTH binding to its receptor melanocortin receptor type 2 (MC2R) sets in motion acute, and subacute changes in the enzymatic activity in the zona fasciculata that yield an increase in production of cortisol. Once secreted, cortisol bioavailability is regulated by binding to circulating proteins: 80% to 90% to corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG) and 5% to 15% to albumin (22). This acts as a reservoir for hydrophobic cortisol, ensuring it is delivered appropriately to tissues with maintenance of the ∼5% free cortisol fraction that is bioactive and can increase to 25% when CBG is absent or inactivated (23, 24). Furthermore, CBG can be cleaved by neutrophil elastase, resulting in a conformational change that reduces the binding affinity for cortisol, allowing targeted delivery of cortisol to sites of acute inflammation (25).

The HPA axis is regulated by negative feedback at multiple levels. Ultrashort feedback loops occur in the hypothalamus (CRH-mediated) (26) and pituitary (ACTH-mediated) through autocrine inhibition (27). Short feedback loops inhibiting CRH secretion occur in the hypothalamus, either through neural projections from the arcuate nucleus in response to CRH (1) or hormonal by ACTH. The latter has been demonstrated via in vitro studies, which has been confirmed to occur in vivo in patients with Addison disease or hypopituitarism (who have baseline elevated CRH), but not in normal subjects (in whom it is assumed long-feedback from cortisol masks this mechanism (28). As cortisol is secreted in response to ACTH, it acts via the GR in long-feedback loops to inhibit CRH and AVP mRNA transcription in the hypothalamus and POMC transcription and post-translational modification (into ACTH) in the anterior pituitary, thereby limiting exposure to glucocorticoids in response to stress (29, 30). This can also occur rapidly (< 20 minutes) through nongenomic, GR-mediated mechanisms, likely acting to prevent pre-formed ACTH release from corticotropes and blocking CRH stimulation, thus inhibiting ongoing pulsatile secretion of ACTH and cortisol (31). Supraphysiological doses of glucocorticoids can suppress HPA axis function through inducing constant, potent, negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary. This is estimated to occur in 48% to 63% of those receiving long-term treatment (32, 33), but has also been demonstrated after short or recurrent courses of high-dose glucocorticoids (34-36). It is likely that interindividual differences in glucocorticoid sensitivity mediate the unpredictability in development of secondary adrenal insufficiency in this setting.

External inputs into HPA axis function come from multiple sources. Central catecholaminergic pathways in the medulla reciprocally stimulate CRH secretion in the hypothalamus, and inhibitory inputs arise from central gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), opioid, and endocannabinoid neuronal systems (16, 17). Ghrelin and leptin have contrasting effects on the HPA axis, the former stimulatory (predominantly acting via AVP), the latter inhibitory (37, 38). The HPA axis is one of the key effectors of the stress response and is tightly linked to the immune system, both regulating and being regulated by it: the immune-endocrine axis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) all increase ACTH secretion either directly or via potentiating CRH stimulation (1, 39, 40).

Circadian/ultradian rhythms

CRH, ACTH, and cortisol, are secreted in a pulsatile manner with levels rising from the early hours of the morning, peaking shortly after waking, and falling throughout the day and evening (1, 41). Reported peak morning serum cortisol concentrations using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; the most accurate current methodology for measurement of steroid hormones) are 350 nmol/L (2.5-97.5th percentiles; 165-635) in males and 323 nmol/L (166-617) in females (42). In an older study which measured cortisol using reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), nadir concentrations were (mean ± SD) 50 ± 30 nmol/L (43), while stressed values in critically ill patients range from means/medians of 744 to 1350 nmol/L depending on the cause, severity, and duration of illness (44-46). Using microdialysis, free tissue concentrations of cortisol retain this pattern in ambulatory healthy volunteers, along with all measurable adrenal steroids and metabolites except for dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) (47). This study confirmed that a drop to nadir levels only occurs following sleep commencement. This circadian rhythm is driven by an increase in secretory pulse amplitude in the morning and a reduction in pulse frequency overnight (1, 48). The circadian pattern of secretion is controlled by light-dark and sleep-wake patterns (through the central clock mechanism of the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus [SCN]), food intake, and stressors (49, 50). Additionally, there is evidence of a native adrenal clock mechanism with daily rhythmic expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) contributing to an intrinsic adrenal circadian rhythm (51). Furthermore, cortisol can act to reset other peripheral clock mechanisms by enhancing the expression of clock-related genes; however, there is no effect on the central clock as SCN neurons lack GR (50, 52). Overlaid on the circadian pattern of secretion is an ultradian rhythm with pulses of ACTH produced every 1 to 2 hours (50). This pulsatility enhances the ability of the HPA axis to respond to stress and loss of the circadian and derangement of ultradian rhythm are some of the first changes in endogenous Cushing syndrome (53).

Sex differences in HPA axis function

Sexual dimorphism occurs in HPA axis function between male and female subjects. This is mediated by interactions with the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and its effector hormones (estrogens, progestogens, and androgens), either directly or indirectly. Other sex effects include the influence of chromosomal genetic factors, and biochemical and structural differences of the central nervous system arising from epigenetic programming during development that impact the integration of complex signals to the PVN (54, 55). These differences in HPA axis function are associated with sexual dimorphism in diseases impacted by HPA axis dysregulation, with women being disproportionately affected by autoimmune disease and major depressive disorders, while men more commonly suffer cardiovascular disease and infection (54). The most striking discrepancy is in the epidemiology of all causes of Cushing syndrome (endogenous cortisol excess), which are heavily biased toward female individuals (56).

In rodent studies, the sex differences in HPA axis function are consistent, demonstrating elevated basal and stress-induced corticosterone levels in female rodents (regardless of the stressor) with more frequent and greater amplitude of secretory pulses measured when assessing diurnal rhythmicity (55). In humans, sex differences are not as well defined, depending on the timing of assessment (basal vs stressed) and the nature of the stressor. No difference was found in serum cortisol levels between men and women when sampled every 15 minutes for 24 hours, despite an increase in the pulse frequency, amplitude, mean ACTH, and area under the curve (AUC) for ACTH in male subjects, suggesting there may be differences in either ACTH sensitivity or negative feedback regulation between males and females (48).

Differences between sexes alter with age, particularly in female individuals, which vary with impact of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis hormonal changes. Young female individuals have lower basal ACTH (57). Basal cortisol levels are elevated in the follicular compared to luteal phase of the menstrual cycle when measured both in serum (total) or saliva (free) (58, 59). In the extremis, HPA axis function becomes progressively more altered from normal physiology through the course of pregnancy, with eventual development of positive, placental CRH–driven feed-forward regulation and exceedingly high cortisol levels approaching parturition (60). As women age, CBG decreases compared to men, but this is not associated with changes in free cortisol (61). Relative to men, older data suggest lower mean 24-hour cortisol levels in premenopausal women, a difference that was lost following menopause, suggesting a relative greater increase in total serum cortisol as women age (62). This is associated with a delay in the onset and shortening of duration of the “quiescent phase” (cortisol persistently < 138 nmol/L) of the diurnal cycle which was more pronounced in aging women.

Following a standardized laboratory-induced psychological stress (Trier Social Stress Test), male subjects exhibit a greater ACTH response than female subjects (except those in the luteal phase) (63), and greater salivary free cortisol peak and during recovery period (64, 65). Stress involving a social rejection trigger may induce a greater cortisol response in female subjects (66), however this finding could not be replicated (67, 68). Physical triggers similarly demonstrate sexual dimorphism in HPA axis response with no difference in response to endurance exercise (69, 70), female participants generating greater cortisol levels following heat and cold exposure (71, 72), while males demonstrate greater salivary cortisol response to noxious stimuli (73). Finally, responses to pharmacological manipulation of the HPA axis differ, with female subjects demonstrating greater response of ACTH and cortisol to naloxone (65), ACTH (and more prolonged cortisol peak) to ovine CRH (74), ACTH and cortisol to combined human CRH and AVP (57, 75), cortisol following dexamethasone-suppressed CRH (76), and salivary free cortisol with ACTH1-24 stimulation (greater in luteal phase) (63). As aging occurs, the responsivity to pharmacological tests of HPA function tends to increase, and this occurs disproportionately so in females (76-78).

The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of sexual dimorphism in HPA axis function are reviewed in depth elsewhere (55), where relevant data is available, sex differences will be covered in subsequent sections of this paper.

Physiological Effects and Therapeutic Use of Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids have pleiotropic effects on a wide range of tissues, and by acting predominantly through the GR, they regulate up to 20% of the genome (4). This expansive repertoire of transcriptional regulation accounts for the extensive and varied physiological regulation, beneficial therapeutic, and significant adverse effects.

In addition to responding to inflammatory stimuli, other stressors induce the HPA axis’ counterregulatory response to return the body to homeostasis. This has been demonstrated with fever, surgery, burns, hypotension, exercise, emotional stress, and hypoglycemia (79-83). The latter forms the basis for the insulin tolerance test as the gold standard for assessing adequate HPA axis function (84, 85). The effects on individual systems coalesce to prepare the body to deal with the stressor and prevent decompensation.

The name for glucocorticoids is derived from the hormones’ actions on glucose metabolism. The metabolic alterations in response to an elevation in glucocorticoid levels function to mobilize substrates for use in energy production. In the liver, glucocorticoids stimulate glycogen synthesis and gluconeogenesis through upregulation of synthetic enzymes, while peripherally cortisol inhibits uptake and utilization of glucose in muscle and fat and potentiates glucagon and catecholamine effects (86-88). The net effect is insulin resistance and mobilization of glucose into the circulation. Hyperglycemia is common with therapeutic treatment, occurs within hours of commencement, and predominantly affects postprandial glucose levels (89, 90). While stimulating lipolysis, glucocorticoids also promote adipocyte differentiation and adipogenesis, and long-term excess glucocorticoid exposure is associated with visceral and central adiposity (91, 92). Weight gain is reported in up to 70% of long-term glucocorticoid users, with a magnitude of 4% to 8% of body weight over 2 years on 5 to 10 mg prednisolone equivalent (93, 94). Furthermore, protein catabolism is stimulated in skeletal muscle, bones, and skin to provide amino acids for use in oxidative pathways (95, 96). With prolonged, excessive exposure to glucocorticoids, this culminates in clinical features such as dermal atrophy, sarcopenia, and osteoporosis (6, 97-99). Additionally, cortisol is necessary for maintenance of adequate circulating volume and blood pressure through interaction with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system to promote salt and water retention, increasing vascular sensitivity to catecholamines and inhibiting AVP (100-103). Glucocorticoids are essential for development in a range of tissues, but most importantly the lung, where they induce fetal lung maturation (104). GR-knockout mice die shortly after birth due to respiratory failure, and exogenous glucocorticoids are administered prenatally (maternally) to accelerate fetal lung development with impending premature delivery (105). Glucocorticoids are similarly important for neural function and in excess can cause a range of neurocognitive side effects which are dose- and duration-dependent but can occur within 1 week of commencement (106, 107). In normal physiological concentrations, glucocorticoids may contribute to neurodegenerative diseases through induction of neuronal cell death (108). Cortisol interacts with the other endocrine systems with induction of growth hormone transcription but antagonism of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and inhibition of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion, 5′-deiodinase, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulsatility, and luteinizing (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion (109, 110). Despite these wide-ranging impacts of glucocorticoids, therapeutically, they are predominantly used for their potent immunosuppressive effects.

Physiologically, the overarching function of glucocorticoids on the immune system is to enhance innate immunity and control inflammation, supporting efficient clearance of pathogens while limiting tissue damage and preventing an overwhelming systemic inflammatory response, thereby returning homeostasis (111). These contrasting pro- and anti-inflammatory effects are determined by the cell type, cellular activation state, stage of the inflammatory response, and dosage of glucocorticoids (1). Glucocorticoids are involved in enhancing the innate immune response through upregulation of some pattern-recognition receptors (toll-like receptor 2 [TLR2]; NOD-like receptors [NLR]P1, NLRP3, NLRC4) to enhance recognition of evolutionarily conserved pathogen/damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMP/DAMPs) (112, 113). This increases activation of transcription factors activator protein 1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) and subsequent induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a synergistic fashion to aid with chemotaxis, and initiation of the immune and acute-phase response to an insult (111). The resultant secretion of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α enhances glucocorticoid secretion, providing a feed-forward mechanism to limit inflammation (1, 114). Subsequent direct inhibition of AP-1 and NF-κB and upregulation of their inhibitors by glucocorticoids downregulates the inflammatory response (111). In the resolution phase of inflammation, glucocorticoids impair neutrophil recruitment and stimulate neutrophil and lymphocyte apoptosis with recruitment and activation of macrophages at the site of injury to promote clearance of cellular debris and tissue/wound healing (111). At therapeutic doses, the immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids predominate with inhibition of leukocyte migration into tissues, neutrophil egress from the bone marrow, induction of eosinophil apoptosis, reduction in circulating lymphocyte counts (T more than B cells) through apoptosis and sequestration, and a reduction in immunoglobulins (115-118). While these immunosuppressant actions of glucocorticoids are harnessed to effectively treat autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, they predispose to opportunistic infections in those on prolonged treatment. The relative risk may be as high as 1.6 compared to placebo, and this risk is increased further by concomitant use of other immunosuppressive or biological therapy (119). There is a particular susceptibility to invasive fungal and viral infections. The infection risk is also dependent on other factors such as the use of additional immunosuppressive agents, age, and comorbidities (120).

Therapeutic uses of glucocorticoids

Since the discovery that cortisone could improve clinical features and markers of inflammation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (121), glucocorticoids have been used widely to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases in oral, parenteral, inhaled, topical, ocular, and intraarticular formulations (6). They have additionally been used as essential components of chemotherapeutic regimens, for their direct cytotoxic effects in lymphoproliferative malignancies, for their antiemetic and orexigenic properties in other cancers, and their anti-inflammatory properties in edematous brain metastases (36, 122). Furthermore, glucocorticoids form part of the backbone of organ transplantation immunosuppression regimens and are utilized in the perioperative setting for nausea and vomiting prophylaxis or to reduce laryngeal edema after endotracheal intubation (123, 124).

Pig adrenal extract was first used to treat Addison disease by William Osler in 1896 and since the mid-20th century, glucocorticoids have been used as life-saving treatment for patients with both primary (also requiring mineralocorticoid replacement) and secondary adrenal insufficiency (125). Unlike in therapeutic treatment of inflammatory disease, treatment of adrenal insufficiency aims to mimic the physiological diurnal secretion of cortisol which is estimated to be in the region of 5 to 8 mg/m2 (body surface area) per day (126). Hydrocortisone twice or thrice daily is the preferred formulation due to the short half-life; however, longer-acting medications may be used to aid with compliance (126). These regimens do not truly mimic physiological secretion which begins prior to waking, leading to development of delayed-release hydrocortisone and the use of continuous subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusions that can more closely mimic the cortisol circadian rhythm (126, 127).

Over time, there has been development/discovery of a wide range of glucocorticoids with varying potencies, degrees of mineralocorticoid activity, and pharmacokinetic profiles. Hydrocortisone is the pharmacologic name for cortisol, and progressive alterations of the molecule have yielded a range of synthetic glucocorticoids, the common feature being a 17-carbon androstane structure of 3 hexane rings and 1 pentane ring, with a hydroxyl group at carbon-11 being critical for glucocorticoid activity (128). Cortisone acetate and prednisone are inactive precursors that require conversion by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1) to the active hydrocortisone and prednisolone respectively (128). Table 1 lists common glucocorticoids used in clinical practice.

Table 1.

Common glucocorticoids used in clinical practice

| Medication | Equivalent dosage (mg) | Anti-inflammatory potency (relative) | HPA axis suppression potency (relative) | Mineralocorticoid potency (relative) | Duration of action (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrocortisone | 20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8-12 |

| Cortisone acetate | 25 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 8-12 |

| Prednis(ol)one | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0.75 | 12-36 |

| Methylprednisolone | 4 | 6.2 | 4 | 0.5 | 12-36 |

| Dexamethasone | 0.75 | 26 | 17 | 0 | 36-72 |

| Betamethasone | 0.6 | 30 | — | 0 | 36-72 |

| Budesonide (inh) | 1.3 | — | 19.5 | — | 24 |

| Fluticasone p. (inh) | 0.6 | — | 34 | — | 24 |

Adverse effects from glucocorticoid treatment are predictable and dose- and duration-dependent (6), and they contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality in those being treated (9-13). In hormone replacement for adrenal insufficiency, traditional doses were supraphysiological based on earlier estimates of endogenous cortisol production (132). More recent studies have focused on replicating the 5 to 8 mg/m2 (body surface area) per day. Guidelines recommend hydrocortisone 15 to 25 mg per day with consideration of weight-based dosing for some patients (126). Weight-based dosing and administration of hydrocortisone in the fasted state has been shown to reduce cortisol area under the curve (AUC) variability and to provide levels closer to physiological replacement than fixed dosing (132). Despite this, cortisol peaks and troughs are respectively higher and lower than physiological secretion and could contribute to development of side effects and reduced quality of life. Increasing the frequency of dosing provides a more physiological profile (126). Furthermore, retrospective studies suggest that higher glucocorticoid doses, and particularly dexamethasone use, are associated with increased risk of adverse metabolic effects; the data for prednisolone are less certain (126, 127, 133). Monitoring of glucocorticoid replacement remains predominantly clinical, and many patients report ongoing symptoms related to glucocorticoid excess or deficiency and metabolic side effects of over-replacement despite treatment with recommended doses (134, 135). As a result of this inaccuracy in management, patients with Addison disease are at risk of premature mortality (136).

In therapeutic uses, dosage of glucocorticoids is disease specific and often protocol driven. For systemic, high-dose glucocorticoids to treat autoimmune/inflammatory diseases or in organ transplantation, regimens typically begin at a moderate-high doses with or without an initial very high-dose induction “pulse” (137, 138). Many regimens use a 1 mg/kg prednisolone equivalent starting dose and wean down over time, often months. Reduction in dosage is dependent on clinical or biochemical measures of underlying disease activity and/or emergence of side effects, with consideration of HPA axis suppression once approaching physiological dosing (138, 139). Addition of alternative immunosuppressants is often used to reduce steroid exposure. Alternatively, in oncology regimens, high doses of glucocorticoids are delivered intermittently to coincide with cytotoxic medications (36). For many of these uses, aside from the initial weight-based commencement dose, little consideration is made to interindividual sensitivity to glucocorticoids and there currently is no mechanism/biomarker to assess the extent of glucocorticoid activity, which is likely to result in many patients being unnecessarily exposed to excess glucocorticoids. The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is a key regulator of glucocorticoid sensitivity and further understanding of how it does so may provide a promising avenue by which to assess an individual's sensitivity.

Glucocorticoid Receptor

The GR is a member of the highly conserved nuclear receptor subfamily 3, which also includes the estrogen, progesterone, androgen, and mineralocorticoid receptors (140). GR is encoded by a single gene: nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1 (NR3C1), located on chromosome 5 (5q31) (141). All members of the family have a similar structure centering around the highly conserved central DNA-binding domain, and heterodimerization of the receptors and ligand promiscuity between the family allow for diverse and complex interactions between the hormones (140). Of note, cortisol, and many synthetic glucocorticoids, are natural agonists of the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), binding with up to 100-fold the affinity of the hormone for GR; however, transcriptional regulation by cortisol via GR is much more pronounced than via MR (142). The MR is protected from excessive cortisol activation by 11β-HSD2 in many key tissues (see section on glucocorticoid activity); however, this is not the case in cardiac myocytes or macrophages, where the MR is key for cellular function and glucocorticoids remain the primary physiological ligand (143). Glucocorticoid function mediated by the MR has been reviewed elsewhere in depth (144-148).

Structure of the Glucocorticoid Receptor

The nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (NR3C1) gene consists of 9 exons, of which exons 2 to 9 encode for the GR protein (149). Exon 1 encodes the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of which 13 variants have been identified, with differing upstream promoter regions, and these appear to be involved in regulation of protein isoform expression, with certain promoter usage related to specific isoforms (150-152).

Exon 1 includes promoters for 9 exon 1 variants, including 2 that can be alternatively spliced into a total of 13 exon 1 promoter variants (153-156). The presence of multiple GR untranslated exon 1 sequences arising from different promoters is seen across species and nuclear receptors (154, 155). In humans, these occur up to 31 kilobase pairs (kb) upstream of exon 2, have variable splice donor sites, and a common exon 2 splice acceptor site that includes an in-frame stop codon, 12 base pairs (bp) proximal to the initial exon 2 ATG, ensuring they are not translated into the GR protein (154). There is no difference in transcript stability between the variants tested, nor translational efficiency (157). Alternative promoter usage has been demonstrated to impact splice variant expression in a number of genes, modulated via transcription factor and cofactor recruitment, which could be important for the expression of different GR isoforms (158).

Full-length GR (GRα-Α) is a 777–amino acid, modular protein composed of 3 major functional domains (140). The N-terminal domain (NTD) encoded by exon 2 comprises the initial 421 amino acids and is the most variable region between nuclear receptors in the same species, and in the same receptor between species (3). The NTD contains the constitutive, ligand-independent transcriptional activation function 1 (AF1), which is essential for maximal transcriptional activation and is important for GR interaction with other transcription factors, chromatin re-modelers, and the basal transcriptional machinery (149). The central DNA-binding domain (DBD) contains 2 highly conserved zinc finger motifs which are critical for binding of GR to glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) in the DNA sequence (159). Additionally, this region also contains a nuclear localization (NLS1), nuclear retention, and nuclear export signal which mediate cellular transport of the receptor. The second zinc finger includes a specific 5–amino acid sequence (D-box) required for canonical receptor dimerization (149). More recent data demonstrate that mutations of this region do not abrogate dimerization completely as previously thought (160). Furthermore, the C-terminal end of the DBD comprises the hinge region, which provides flexibility for conformational change and allosteric interactions with transcription cofactors, the basal transcriptional machinery, and DNA itself (161). The hinge region also participates in bidirectional signaling between the components of the receptor in response to DNA binding (162). A final ligand-binding domain (LBD) forms the carboxy-terminal portion of the protein. The LBD forms a hydrophobic pocket necessary for glucocorticoid binding, in addition to mediating crucial interactions with coregulators, other transcription factors, and cytoplasmic chaperone proteins (163). Also included in the LBD are the ligand-dependent transcriptional activation function (AF2) and a second nuclear localization signal (NLS2) (149). Structural analysis of the LBD demonstrates that it may play a role in the ability of GR to dimerize in addition to impacting the conformation of these dimers (164).

Function of the Glucocorticoid Receptor

The canonical understanding of GR function begins with unliganded GR residing predominantly in the cytoplasm, bound to a multi-protein anchoring complex. This multi-protein complex includes chaperones (heat shock protein 90 [hsp90], hsp70), immunophilins (FK506-binding protein 5 [FKBP5], FKBP4), and tyrosine kinases (c-Src), which prevent GR from acting as a transcription factor while maintaining a conformation with a high affinity for glucocorticoid (165). Ligand binding to GR induces a conformational change in the receptor leading to exchange of FKBP5 for FKBP4 within the components of the multi-protein complex (166). This leads to dissociation of some components of the multi-protein complex and exposure of the NLS1 and NLS2, facilitating nuclear translocation of GR where it can modify target gene expression via a number of mechanisms (Fig. 2) (167). The affinity of the GR ligand alters the diffusion coefficient and nuclear residence time, with higher-affinity ligands inducing longer nuclear translocation (168, 169).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) action. GR is maintained in the cytoplasm by an anchoring complex [1] which modifies the conformation of GR to allow high affinity for glucocorticoids [2]. Glucocorticoids cross the membrane where they can be activated/inactivated by 11β-ΗSD isoforms [3]. Binding of active glucocorticoid to GR leads to dissociation of the complex [4]. GR can have a series of nongenomic effects in the cytoplasm (see text for details), or predominantly enters the nucleus. GR binds to open chromatin (determined by pioneering transcription factors) [5] where it can: directly activate or repress transcription at canonical GREs, direction of regulation determined by cofactors, gene, other transcription factors [6]; repress transcription at nGREs [7]; interact with other transcription factors either as a monomer or dimer at shared binding sites to enhance/repress transcription [8, 9], whether this can occur without direct DNA binding (tethering) [8] has been brought into question; or compete for binding sites with other transcription factors [10]. Unliganded GR is bound throughout open chromatin [11] and dissociates in favor of glucocorticoid-bound dimers upon exposure. Created with Biorender.com.

Homodimers of GR can bind to the consensus sequence of GRE in the promoter, intron, or exon of target genes to induce transactivation (149). The GRE consensus sequence consists of an imperfect palindrome with 2 half-sites, each of which cooperatively bind 1 subunit of the GR homodimer, separated by a crucial 3-bp spacer which is necessary to allow for appropriate GR conformation (3). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) studies have demonstrated that in the absence of glucocorticoid stimulation, there is widespread chromatin occupancy by GR monomers, which dissociate in favor of GR dimer binding to GRE in response to glucocorticoids (170, 171); GR occupation of GRE leads to the recruitment of cofactors and chromatin remodeling complexes to positively regulate transcription by RNA polymerase II (RNApolII). The DNA sequence of the GRE alters GR confirmation, activation site usage, and transcriptional activity with differences seen with as little as a 1-bp alteration (172). Binding to GRE, however, does not always lead to transactivation. Occupation of canonical GREs by GR has been shown to induce suppression of target genes, suggesting that other regulatory mechanisms (eg, recruitment of certain cofactors) can modulate GR-GRE activity (149). Furthermore, negative GRE (nGRE) with a more variable consensus sequence have been identified that repress transcription upon binding of 2 everted GR monomers (preventing interaction of the D-box motif and hence dimerization), involving recruitment of corepressors and histone deactylases (173, 174). In addition to direct DNA-binding mechanisms, GR is thought to interact with DNA-bound transcriptions factors (tethering), either amplifying (eg, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; STAT3) or suppressing (eg, NF-κB) their function through means such as altering coactivator binding or hindrance of interaction with transcriptional machinery (2, 175-177). Recent data have brought this mechanism into question. Substitution of a cysteine residue in the first zinc finger for glycine completely abrogates GR DNA binding but leaves all other functions/domains and post-translational modification intact (178). This mutation demonstrates perinatal lethality (similar to GR knockout), and while tethering was demonstrable, no changes in associated gene activation/repression were detected in response to ligand when assessed by multiple means, suggesting that DNA binding by GR is necessary to alter gene expression, potentially through failure of interaction with key coactivators (eg, GRIP-1) (178). Furthermore, only a small proportion of GR-regulated genes are found at sites with concomitant NF-κB and AP-1 binding, and the majority of those that are contain a classic GRE, suggesting that tethering is not widespread at a genome level (170). Monomeric GR can even repress inflammatory gene transcription by binding to a cryptic GRE half-site within the AP-1 response element in the absence of AP-1 binding (179). A final genomic mechanism of transcriptional regulation by a composite of GRE binding and tethering to/interacting with transcription factors bound at an adjacent DNA response element has also been demonstrated (eg, STAT3 and 5, AP-1) (2, 175). At the same locus, differing interacting transcription factors can variably upregulate or downregulate the gene in response to glucocorticoids (170, 180). It may be that the formerly demonstrated DNA-independent tethering actually represents composite binding and requires direct DNA interaction with a GRE (175).

Some effects of GR have been demonstrated to occur rapidly upon ligand binding—within seconds to minutes—suggesting a nongenomic mechanism (3, 181). Glucocorticoids can activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) pathway through phosphorylation within minutes of administration in a GR-dependent, mRNA-independent manner; this pathway is essential for NF-κB phosphorylation and activation (182). This pathway is also involved in GR-dependent upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity in vascular endothelial cells treated for 10 minutes with dexamethasone, an effect resistant to transcriptional inhibition (182). Furthermore, GR interacts with p65 and IκBα in the cytoplasm and glucocorticoids can reduce p65 entry into the nucleus (183). Similarly, GR can prevent AP-1 activity by associating with c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) via the LBD of GR, inhibiting phosphorylation and hence activation of JNK, subsequently competitively inhibiting active JNK from phosphorylating c-Jun in AP-1 (184). Glucocorticoid-mediated liberation from the cytoplasmic multi-protein complex can lead to GR translocation to the mitochondria and induction of apoptotic pathways without gene regulation, and this correlates with lymphocyte sensitivity to glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis (185). Furthermore, membrane-bound GR has been demonstrated in a range of tissues, is upregulated in immune cells in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, and rapidly activates pro-apoptotic, immune regulation, and metabolic pathways upon exposure to membrane-impermeable glucocorticoids (181, 186, 187). Unliganded GR is essential for T-cell receptor signaling at the membrane through LCK/FYN kinase activation, and glucocorticoid treatment causes dissociation of GR from the complex preventing this (188, 189). Finally, liberation of the other components of the anchor complex allows them to participate in signal transduction pathways such as c-Src's activation of pathways leading to annexin-1 phosphorylation and inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolism (190). At least a portion of the described nongenomic effects may even be independent of GR (181). Glucocorticoids have been shown to rapidly decrease via protein kinase A, or increase via protein kinase C, basal or stimulated intracellular calcium concentration in a cell type–specific manner which is not affected by the GR antagonist mifepristone (also known as RU-486) or cycloheximide (mRNA synthesis inhibitor) treatment (191, 192). It is thought these effects are mediated by nonspecific interactions between glucocorticoids and the cell membrane, which alter its physiochemical properties and the function of membrane-associated proteins, and may mediate some of the immunosuppressive benefits at supratherapeutic doses (eg, pulse methylprednisolone treatment) (181, 193).

Glucocorticoid Receptor Isoforms

While a significant body of work has developed an in-depth understanding of canonical GR function, a number of splice and translation initiation isoforms have recently been discovered which diversify GR function as detailed below and shown in Fig. 3. Both splice and translational isoforms are conserved across species, having been described in analysis of various tissues of mice, rats, guinea pigs, pigs, sheep, dogs, and zebrafish (5, 194-196). Other splice variants have been described in the slender African lungfish (197). An example of conservation of GR isoforms across species is derived from work conducted in the placenta, where 8 known GR isoforms are detectable in human (152, 198, 199), mouse (200), guinea pig (201), and sheep placentas (202). Data presented here relate to the human GR.

Figure 3.

Splice and translation initiation isoforms of the glucocorticoid receptor. NR3C1 gene is composed of 9 exons, exon 1 contains 11 untranslated promoter variants, while exons 2 to 9 encode the GR, which occurs as a number of splice, and translational initiation isoforms, see text for details. Abbreviations: AF-1, transcriptional activation function 1; DBD, DNA-binding domain; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; H, hinger region; LBD, ligand-binding domain; NTD, N-terminal domain. Created with Biorender.com.

Alternative splice site variants

Gene splicing is the process of removing noncoding introns and joining protein-encoding exons of pre-mRNA to form mature mRNA that can be translated (203). This process is mediated by a large ribonucleoprotein complex, the spliceosome, under the guidance of regulatory sequences within the pre-mRNA which recruit splicing factors to control splicing. Alternative splicing is a common feature of eukaryotic gene expression and can generate multiple mRNA isoforms from a single gene (203). Direction of alternative splicing can occur through variation in RNA-binding protein recruitment (eg, heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, serine-arginine repeat proteins), RNA-RNA base pair interactions and pre-mRNA secondary structure, and interactions between the spliceosome and histones/chromatin structure and RNApolII (204).

The full-length GRα mRNA results from splicing of exons 2 to 8 and the end of exon 8 to a donor site at the beginning of exon 9—9a; this results in the majority of exon 9 forming the 3′ UTR (149). Our understanding of GRα-A function is as above, or as described for its other translational isoforms in the subsequent section.

GRβ

GRβ is generated through alternative splicing of exon 8 to a distal splice acceptor site in exon 9—9β (205). The resulting protein is identical to GRα through to amino acid 727 (NTD, DBD, and part of LBD) with a further nonhomologous 15 amino acids. This results in a shorter protein lacking α-helix 12 of the LBD, which is essential for formation of the hydrophobic pocket, thereby preventing glucocorticoid binding, and which forms part of the AF2 domain, thereby altering cofactor interactions (206-208). Alternative splicing to GRβ can be directed by dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)-induced serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 9 (209). The only known ligand of GRβ is GR antagonist mifepristone (210). GRβ has been found to be a dominant negative regulator of GRα activity in a range of tissues. It is expressed predominantly in the nucleus and can form nontransactivating heterodimers with GRα, and competes for both coactivator and GRE binding, preventing glucocorticoid-mediated GRα activity (211-214). Nuclear localization of GRβ is not universal and cytoplasmic expression has been demonstrated in a number of cell types/lines (human monocytes, COS-1, HeLa, U2OS) (206, 210, 213). Furthermore, mifepristone has been variably shown to induce nuclear translocation of GRβ in a cell type–specific manner (210, 215). GRβ mRNA is detectable in almost all tissues and cells, but with expression at a fraction of GRα levels, and the protein has been detected in most tissues, but this has not been consistently demonstrated (213, 216). In patients with Cushing syndrome compared to healthy controls, the relative expression of GRβ mRNA was higher in hypercortisolism and declined after successful treatment. In parallel to this, binding affinity of dexamethasone was lower in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in patients with hypercortisolism than in healthy controls and increased after treatment; however, this difference was not seen in skin fibroblasts (217-220).

While traditionally thought of as acting solely as an inhibitor of GRα activity, GRβ has been demonstrated to have its own, unique transcriptional regulation repertoire, while also sharing some regulatory functions with GRα (eg, repression of IL-5 and IL-13 via histone deacetylase recruitment to their promoters) (214, 215, 221, 222). The mechanism behind this is not fully elucidated, however in vitro data has been confirmed to be active in vivo from a study of GR wild-type and knockout mice which demonstrated that the effect of GRβ on gene transcription in the liver varies, dependent on the presence or absence of GRα (222). Furthermore, despite lacking the α-helix 12 and presumed interruption of the AF2 domain, GRβ can still bind corepressors in the presence of mifepristone to a similar extent to GRα, meanwhile, coactivator binding on dexamethasone stimulation is abrogated (206). Further work is needed to elucidate the mechanisms of GRβ's non-GRα-dependent functions.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines can increase GRβ expression through a number of mechanisms, and it is thought that this contributes to glucocorticoid resistance seen in inflammatory illnesses such as sepsis (223, 224). The serine/arginine-rich proteins (SRps) are a highly conserved family of proteins involved in regulating mRNA splicing through preferentially binding to different splice sites and initiating spliceosome formation. SRp30c and SRp40 have been shown to favor GRβ splicing of GR mRNA in response to IL-8 or bombesin, while SRp20 expression favors GRα splicing (225, 226). The effect of these SRps in regulating GR mRNA splicing is supported by the presence of predicted binding sites for each isoform in their respective segments of GR exon 9 (167). Furthermore, micro-RNAs can alter splice isoform expression; micro-RNAs are small, noncoding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to mRNA and causing degradation of the transcript (227). In T cells, expression of microRNA (miR)-124 reduces both GRα mRNA and protein resulting in a relative increase in the proportion of GRβ mRNA (which was unchanged) (223). Additionally, miR-144 has been demonstrated to be targeted to the 3′ UTR of GRβ mRNA; mutation of miR-144 or blockade leads to downregulation of GRβ, and overexpression leads to increased expression of GRβ (228).

GRγ

GRγ was first discovered in cancer cell lines and upregulation in these tissues is associated with glucocorticoid resistance (229, 230). This isoform results from alternative splicing of the intron between exons 3 and 4, resulting in addition of a single arginine residue between the DNA-binding zinc finger motifs (229). This insertion resides close to the NLS1 domain and unliganded, GRγ shows a predominantly cytoplasmic distribution compared to GRα, with slower nuclear import in response to dexamethasone, which is associated with delayed onset of transactivation (231). Interestingly, there is a concentration of GRγ residing close to the cell membrane particularly concentrated around membrane ruffles, and potentially this isoform may be the putative membrane GR (231). GRγ typically accounts for around 3.8% to 8.7% of total GR mRNA (232, 233); however, as much as 40% of total GR has been seen in PBMC of patients with glucocorticoid-resistant multiple sclerosis (who also had reduced total and GRγ expression compared to glucocorticoid-sensitive controls) (234). Additionally, GRγ mRNA is upregulated in PBMC from patients with glucocorticoid-resistant immune thrombocytopenic purpura (235).

The GRγ gene regulatory profile and DNA-binding regions show up to 94% similarity to GRα in response to glucocorticoids (162, 236), but despite a higher affinity for GR binding sites than GRα, GRγ has been shown to have approximately 50% of the transcriptional activity (229, 230). In the unliganded state, transcriptional regulation compared to GRα is more distinct (231). These differences in GRγ-specific regulation of genes appear to be in part directed by the DNA sequence at the GR binding site (162, 172). Additionally, GRγ demonstrates an abundance of mitochondrial function–related gene pathways in transcriptome and protein interaction studies relative to GRα, which is associated with increased mitochondrial mass, basal (unliganded) respiration, and ATP production in HEK cells overexpressing each isoform (231).

To date, this isoform has only been described using measurement of RNA/cDNA (229, 230, 232, 233), or functional reporter assays in cell lines (229, 230). With only one additional amino acid, it would be impossible to separate this isoform from GRα using Western blot methodology, the most common approach to isoform protein measurement.

GR-A

GR-A was first described in a resistant multiple myeloma cell line and is formed through alternative splicing of the 3′ exon 4 splice donor site to the 5′ donor site in exon 8 (237). The absence of exons 5 to 7 yields a 65-kDa receptor lacking the amino portion of the LBD, including a nuclear localization signal and AF2 (237). The physiological activity of this isoform is unknown and to date has only otherwise been confirmed in the placenta (198). However, a 67-kDa isoform, which may represent GR-A, was the predominant isoform expressed in nasal mucosa of healthy volunteers and polyps from patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (although this study found conflicting findings using 2 different GR antibodies) (238) and was also detected in human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex at higher levels than GRα-A (239). No changes in GR-A expression were seen in hippocampal or prefrontal cortex of mice exposed to chronic unpredictable stress, unlike other isoforms.

GR-P

GR-P mRNA was first recognized in a glucocorticoid-resistant multiple myeloma cell line where its upregulation (in combination with downregulation of GRα) occurred at emergence of the resistant population followed by eventual downregulation over months whether or not there was ongoing exposure to dexamethasone (240). The isoform is formed by failure of splicing between exon 7 and 8, with inclusion of the initial segment of the intervening intron (237, 240). The resulting receptor lacks the carboxy-terminal half of the LBD, including the dimerization signal and AF2, resulting in a 74-kDa protein that fails to bind ligand (241).

Subsequently, GR-P has been shown to be present in normal PBMCs or lymphocytes where is constitutes 4% to 24% of total GR mRNA and is correlated with total GR per cell using dexamethasone binding assays (217, 242, 243). Additionally, this isoform has been demonstrated in human placenta (where it is increased in those undergoing induction of labor or cesarean section) (150, 198, 199, 244), postmortem hippocampus and prefrontal cortex samples (in the latter, mRNA expression was lower in suicide-completers compared to controls) (245), leukemic cells of glucocorticoid-naïve multiple myeloma, acute lymphoblastic/myeloid leukemia (ALL/AML), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients, and ovarian, hepatocellular, prostate, and ACTH-secreting small cell lung cancer cell lines (241, 242). GR-P was not detectable in paraganglioma samples (242). There is significant variability of the level of GR-P expressed in these malignancies; however, in most samples it is greater than in healthy lymphocytes. Additionally, GR-P mRNA is expressed to a greater extent in marrow mononuclear cells from patients with T-ALL compared to B-ALL (246). GR-P expression in these studies did not find any association with glucocorticoid resistance (242). DMS-79 cells (ACTH-secreting small cell lung cancer line), known to be resistant to glucocorticoids, showed no detectable dexamethasone binding with an abundance of GR-P protein detected (241). However, this glucocorticoid resistance is likely mediated by negligible expression of GRα, as transfection with GRα into the similar COR L24 cell line restored glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional activation and repression (247).

Transfection studies have demonstrated that GR-P alone does not activate a known glucocorticoid-responsive reporter (mouse mammary tumor virus-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; MMTV-CAT) (241). However, GR-P modulates GRα activity in a cell type–specific manner. In COS-1 (monkey kidney fibroblast; lacking endogenous GR) and HeLa (human cervical epithelial carcinoma; expressing endogenous GRα) and 2 multiple myeloma cell lines, GR-P increased dexamethasone-stimulated luciferase reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner when present with GRα (242). In contrast, in the CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) cell line, GR-P co-transfection reduced dexamethasone reporter stimulation by 50%. Furthermore, GR-P may undergo glucocorticoid-mediated negative feedback, with GR-P mRNA significantly decreased following glucocorticoid treatment in human placenta, with a greater extent using dexamethasone compared to hydrocortisone (150).

Other splice variants

While the splice variants discussed above have been described and some of their effects on function characterized, it is possible there are many more isoforms that could play a role in the modulation of GR function. In a study considering 97 healthy volunteers, 18 burn patients, and 35 patients with asthma, an additional 21 GR splice isoforms were identified in RNA extracted from buffy coat (248, 249). These arose through retention of varying lengths of introns B, D, G, and H, with many lacking the LBD and/or DBD. Only 2 variants have been characterized and whether they were expressed to a greater extent in health or disease was not reported. GR-S1 and GR-S1(-349A) were identified in a single subject, both retain intron H (between exon 8 and 9), with the latter also containing a single nucleotide deletion at position 349 that induces a frameshift with premature stop codon and truncated protein of 118 amino acids (249). These demonstrate 10% and < 1% of the transactivation potential of wild-type GR in a luciferase assay; however, the latter had greater than 10-fold the activity of wild-type at higher hydrocortisone concentrations. This augmented response is abrogated by removing the 3′ UTR, which is known to reduce the stability or interfere with the processing of mRNA. Another of these variants had previously been reported: GRΔ313 to 338 (250). This GR has a 78-bp, 26–amino acid deletion of exon 2, downstream of AF1. Unlike the larger study, this isoform was not detected in any immune cells but was expressed in lung, adipose tissue, thyroid, and salivary gland; no functional studies were undertaken (250).

Alternative translation initiation variants

Translation of mRNA into protein by the ribosomal complex begins at a start codon (AUG) which encodes for methionine. Scanning of mRNA by the 40S subunit of the ribosome stops upon recognition of AUG by the complementary tRNA, instigating formation of the remainder of the ribosome complex and initiation of protein translation (251). The base pair context (Kozak context) in which AUG is placed affects the ability of the 40S subunit to recognize the start codon and begin translation, allowing alternative translation initiation at downstream AUGs (251). The process of ribosomal leaky scanning involves translation initiation at multiple AUGs whereby the 40S subunit will not reliably begin translation at the proximal AUG with suboptimal Kozak context, but it will scan past and commence at a more optimal downstream AUG (252, 253). The frequency of recognition of a start codon can be altered by mRNA secondary structure downstream of the first AUG, availability of eukaryotic initiation factors, or queueing of ribosomes at downstream codons (251-253). Ribosomal shunting is the process of discontinuous scanning of mRNA that allows the 40S subunit to bypass sections of the 5′ UTR directly to downstream AUG codons (252). The mechanisms by which this occurs are not completely understood but may be dependent on upstream short open reading frames and the presence of complex stem-loop structures in mRNA (252-254).

The human GR gene includes 8 N-terminal AUG codons within exon 2. Mutational studies have shown that translation initiation at each of these codons is responsible for the production of N-terminal translational isoforms of GRα: GRα-A (94 kDa; full-length GR), GRα-B (91 kDa), GRα-C1-3 (82-84 kDa), and GRα-D1-3 (53-56 kDa) (194). The Kozak context for the first start codon is suboptimal, and placement within the optimal context leads to an absence of GRα-Β and significant reduction in GRα-C1-3, suggesting that these isoforms are generated through ribosomal leaky scanning (194, 255). However, insertion of scanning inhibitory structures in upstream mRNA at some locations but not others could inhibit expression of GRα-D1-3, in addition to GRα-C1-3, suggesting ribosomal shunting is responsible for translation initiation of both C (in part) and D isoforms (194). As all other GR splice variants described to date contain an intact exon 2, it is expected that alternatively spliced translation initiation isoforms exist (eg, GRβ-C3), resulting in 40 potential isoforms; however, only the GRα translational isoforms have been confirmed (3, 199).

Translation initiation isoforms of GRα have progressively shorter NTD, and truncation of this domain alters interaction with cofactors and the transcriptional machinery (3), but does not affect dexamethasone binding affinity, receptor half-life, or GRE binding capacity (at genes for H+/K+ ATPase subunit α, vitamin D receptor, NF-κB inhibitor α [IκBα], caspase 6, and granzyme A [GZMA]) when expressed alone in U2OS cells (256). While not tested, given that the NTD is involved in AP-1 interaction, it could be expected this function may be altered (177). As a result, these isoforms have been shown to have both shared and unique gene regulatory profiles upon stimulation with glucocorticoid (194, 256-259). The various translational isoforms of GRα contribute to tissue specificity of glucocorticoid activity, leading to an alteration in glucocorticoid response. This is evidenced by varying levels of isoforms expressed in different cells/tissues (194, 198, 257), contrasting effects of some isoforms on cellular function (eg, apoptosis) (258), or differential activation of the same function in different cells (257), and changes in isoform expression occurring during cellular (259) or organ (239) maturation, or in response to different disease states (198).

GRα-A

GRα-A is the canonical full-length GR (777 amino acids, 94 kDa) and much of the earlier described understanding of the function of GR is thought to be mediated by this isoform. Hence only features specific to this isoform are detailed here. As with other isoforms, expression of GRα-A changes through development. In the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, neuronal GRα-A expression increases from birth through to adolescence where it peaks, before falling and remaining stable throughout life (239). GRα-A protein expression is stimulated in PBMCs by LPS and peptidoglycan but not lipoteichoic acid (260). GRα-A expression is reduced in PBMC of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma compared to healthy volunteers with no change in GRβ, leading to a reduced GRα-A:GRβ ratio, which is thought to contribute to glucocorticoid resistance in these diseases (261). GRα-A mRNA is elevated compared to controls in PBMC of patients with chronic adrenal insufficiency on glucocorticoid replacement, but not those with acute, induced hypocortisolism (metyrapone test) (217). Furthermore, GRα-A mRNA is reduced in the neutrophils, monocytes, skeletal muscle, and subcutaneous adipose tissues of critically ill patients in an intensive care unit at up to 4 weeks (262). Other GRα translational isoforms were not considered in these studies.

Interestingly, despite being the prototypical isoform, GRα-A expression in the placenta is low relative to other isoforms, making up less than 5% of nuclear receptor expression and even lower in the cytoplasm (198, 199). It thought that due to this, the interaction of GRα-A with other isoforms contributes to the sex-specific response of the fetus to excess glucocorticoid exposure: relative resistance in males (GRβ) and hypersensitivity in females (GRα-C, GRα-D) (263).

GRα-B

GRα-B results from translation initiation at the second AUG codon, producing a 751–amino acid sequence of 91 kDa, retaining all the AF1 domain. GRα-B is expressed in a tissue-specific manner, being highest in the rat liver and thymus, where it is more extensively expressed than GRα-A (194). Additionally, GRα-B is one of the most abundant isoforms in CD3+ T cells (257), and dendritic cells switch isoform expression following maturation to GRα-Α and GRα-Β rendering them sensitive to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis and resistant to glucocorticoid inhibition of antigen uptake (259). Most studies report similar magnitude of transcriptional regulation and apoptosis induction to GRα-A when transfected into cells in isolation using GRE, MMTV, and NF-κB reporters, demonstrated in COS1, U2OS, and Jurkat T-ALL cell lines (194, 256-258). One study found a 1.5- to 2-fold elevation of transcriptional activation compared to GRα-A despite a lower protein expression for equivalent vector transfection (255); this could be explained by the greater expression of an 83-kDa “degradation product” in the GRα-B transfected cells, as this is now known to correspond to the more active GRα-C isoform. Despite a similar magnitude of effect on transcription as GRα-A, GRα-B has been shown to regulate fewer genes and a proportion of distinct genes to other isoforms (194, 256).

GRα-C 1-3

The GRα-C isoforms 1 to 3 are 692–, 688–, and 680–amino acid proteins with molecular weight between 82 and 84 kDa, generated from further downstream start codons (still upstream of the AF1 domain—residues 187-244) (264). GRα-C1 and GRα-C2 isoforms have a similar GRE-driven luciferase reporter response to dexamethasone as GRα-A and GRα-Β in both COS1 and U2OS cells. GRα-C3 appears to be the most transcriptionally active GR isoform, with the greatest luciferase and MMTV reporter activity on dexamethasone stimulation across a range of receptor and dexamethasone levels (194, 264). In addition to being more effective at transactivation, GRα-C3 regulates the most total and distinct genes of any translational isoform (194) and displays a completely different transcriptome to wild-type GR in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (265). This renders GRα-C3-expressing cells more sensitive to glucocorticoids through multiple mechanisms. GR-null osteosarcoma cell lines (which are resistant to glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis) are rendered sensitive by stable-transfection with GRα-C3, and dexamethasone induces apoptosis to a greater extent than GRα-Α through enhanced inhibition of NF-κB and nGRE-mediated inhibition of anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-XL, survivin, and cIAP1 (258). This translates to earlier induction of apoptosis (12 hours vs 20 hours in other isoforms), and a greater extent of apoptosis 48 hours after stimulation (50% vs 30% in GRα-A), and co-expression of GRα-A and GRα-C3 increases cell death by 19% (256). GRα-C3-expressing Jurkat T-ALL cells showed similar rates of dexamethasone-induced apoptosis (50% at 48 hours) with nGRE-mediated inhibition of anti-apoptotic MYC and miR-17, and GRE-mediated expression of pro-apoptotic BIM, miR-15b (257). The underlying mechanism of GRα-C3 hyperactivity compared to other isoforms appears to be due to steric hindrance of residues 98 to 115 (particularly Asp101) which, when unmasked by the shorter N-terminal of GRα-C3, improves recruitment of specific coactivators to the AF1 domain when bound to DNA (particularly CBP/p300) (264).

GRα-C3 is expressed most abundantly in rat pancreas and colon (194), and it is not detected in human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (239) or in either immature or activated dendritic cells (259). In the placenta, GRα-C3 is higher in female fetuses than male (198), increased in male preterm births compared to term, reduced in female preterm placentae (199), and increased with maternal alcohol intake (244). This isoform represents 10% to 20% of GR in T cells and can be upregulated in response to concanavalin A activation (257). While varying levels of GRα-C3 in tissue is expected to vary the cellular sensitivity to glucocorticoids, this isoform also appears to have both tissue- and gene-specific regulation of target genes. When comparing apoptosis stimulation in Jurkat T-ALL and U2 osteosarcoma cells, apoptosis-related genes AKAP13, ATG12, CDKN2D, GZMA, ING1, ITPR1, SATB1 were commonly regulated by GRα-C3 between cells, but most other modulated apoptosis pathway genes were cell type–specific (257). Furthermore, there appears to be promoter-specific regulation, with higher amounts of CBP/p300 and RNA polymerase II recruitment and acetylated histone H4 at the GZMA promoter when activated by GRα-C3 compared to other isoforms, a change that was not seen for IκBα, which was also regulated by this isoform (256).

GRα-D 1-3

GRα-D1-3 isoforms have the shortest NTD, consisting of sequences of 462, 447, and 441 amino acids, generating proteins of 53 to 56 kDa. Unlike the other translation initiation isoforms, the GRα-D isoforms reside primarily in the nucleus both liganded and unliganded (194, 256). Deletion of the residues 98 to 335 (present in GRα-A, -B, and -C, but not -D) of GRα-A leads to a GR with similar nuclear localization to the GRα-D isoforms, the thought is that changes in the conformation of the protein resulting from this region being absent exposes either the nuclear localization and/or nuclear retention domains (258). GRα-D isoforms have the lowest transactivation activity and regulate the fewest total and distinct genes in COS1 and U2OS cells, and increasing concentrations do not alter GRα-A activity (194, 256). In cell-free in vitro coimmunoprecipitation studies, GRα-D isoforms interact with NF-κB to a similar extent to GR wild-type (258). However, when expressed in GR-null osteosarcoma cells, GRα-D isoforms do not readily interact with the p65 subunit of NF-κB; these isoforms do not induce apoptosis and regulate the fewest apoptosis-related genes (256, 258), and either do not alter basal NF-κΒ reporter activity (258), or reduce it by 50%, associated with dexamethasone inhibition of cytokine (TNF-α, IL-8, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) release in response to LPS (256). It is postulated that this reduction in NF-κB inhibition is due to the need for GR to be localized in the same compartment as the p65 subunit for optimal interaction of these proteins, the latter of which is predominantly expressed in the cytoplasm (258). Furthermore, Jurkat T-ALL cells transfected with GRα-D3 were also resistant to dexamethasone-induced apoptosis but did downregulate the pro-inflammatory genes inducible T-cell costimulatory, IL-8, TNF-α, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, TNF superfamily member 14, lymphotoxin-β, GM-CSF commonly to GRα-C3 (257). GRα-D3 appears to also regulate gene expression in a glucocorticoid-independent manner, having been shown to activate certain promoter regions by ChIP-seq, unlike other isoforms (256). Interestingly, a 50-kDa GR protein, likely one of the D isoforms, was upregulated in PBMCs isolated from human donors following incubation with LPS and peptidoglycan, suggesting a potential role in the innate immune response (260).

Like the other translation initiation isoforms, GRα-D isoforms display variation in tissue expression. In rodents GRα-D are expressed to the greatest extent in spleen and bladder, with negligible expression in bone (194, 256). GRα-D isoforms represent 5% of GR expressed in the CD3+ T cells and GRα-D is the predominant isoform expressed in immature dendritic cells (257, 259). In the human cortex, GRα-D is the most abundantly expressed in neonates, before falling through childhood and adolescence with some recovery in adults (239). In keeping with this, samples from neonates < 130 days old displayed strong GR immunohistochemistry staining in the nuclei of pyramidal neurons which progressed to greater soma staining in older tissue samples. Additionally, GRα-D1 is upregulated in the dorsolateral prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (266, 267), and in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (compared to uncinate mucosa of healthy volunteers) (238). Sexual dimorphism is seen in the brain, with unstressed female mice expressing GRα-D isoforms to a greater extent than males in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, with chronic stress leading to a reduction in cytosolic expression in females and increased nuclear expression in males (268). GRα-D isoforms account for the majority of GR expressed in human placenta, with the D1 isoform being the only nuclear isoform detected in human umbilical endothelial cells (198, 199). Finally, gestational alcohol consumption was associated with a reduced frequency of GRα-D detection in placental extract cytoplasm lysate (244).

Exon 1 promoter variants

The GR exon 1 promoter variants demonstrate variable expression between tissues, and are associated with expression of certain GR isoforms, suggesting they may contribute to tissue specificity of glucocorticoid action (152, 155, 156, 269). Variant 1C3 and 1H are the most widely detectable between tissues, and 1D appears to be exclusively expressed in the hippocampus (155). Expression of these exon 1 promoter variants is altered in response to inflammation in human placenta and varies depending on sex of the fetus (150, 152). This is associated with altered protein expression of various GR isoforms depending on sex, with different patterns of change in males and females in response to maternal asthma during pregnancy (152). In multiple cell types, exon 1 variant 1A3 is associated with an increase in GRα-B relative to GRα-A protein expression (157), while 1B is correlated with GR-P, and 1C with GRα mRNA (243). In suicide-completers, increased methylation in the 1J and 1C promoters in prefrontal cortex was associated with reduced GR-P mRNA expression (245). Variants 1B and 1C are downregulated in response to glucocorticoid treatment of trophoblast cell lines in vitro (150), whereas the distal three 1A splice variants and 1I are upregulated by dexamethasone in T but not B-cell ALL lines (154, 156, 270). Using luciferase reporter assays, 1B and 1C (or a combination) demonstrate varying efficacy in driving luciferase activity dependent on cell type (269). Overall, the 1A variants appear to be more responsive to glucocorticoid-mediated regulation than 1B and 1C (157, 270). Transcription factor binding sites have been identified in a number of the promoter regions that may explain the differing tissue distribution of these variant transcripts, including: SP1, AP-1, AP-2, YY1, NGF-1A, NF-κB (p65), IRF 1/2, Nur77, COUP, c-Myb, c-Ets, and nGRE (the latter 3 appear to form a unit mediating glucocorticoid regulation of those exon 1 variant transcripts that are glucocorticoid-responsive) (152, 154, 180, 245, 269, 271). Taken together, these data suggest that the multiple exon 1 promoter variants allow diversification of GR transcriptional regulation between cellular environments and may contribute to splice variant control of downstream isoforms. More work is needed to understand how expression of these exon 1 promoter variants are controlled and how they affect downstream GR isoform protein expression.

Post-Translational Modification

Post-translational modification involves the covalent modification of GR, altering protein stability and interaction with other proteins and hence cellular localization and transcriptional activity (149).

Phosphorylation of GR is the most well-described post-translational modification, which occurs at a number of serine and tyrosine residues, predominantly in the AF1 domain, under the control of phosphorylating kinases (cyclin-dependent kinases, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases [MAPKs], JNKs, extracellular signal-regulated kinases [ERKs], and glycogen synthase kinase 3β [GSK-3β]) and dephosphorylating phosphatases (protein phosphatase [PP]I1, PP2a, and PP5) (149). The effects of phosphorylation are both site and kinase dependent. Phosphorylation of Ser211 by p38 induces a conformational change in AF1 favoring coregulator recruitment and thereby enhancing transcriptional activity, yet phosphorylation at the same residue by ERK or JNK yields transcriptional activity that is relatively reduced (272). In general, phosphorylation by ERKs, JNKs, or GSK-3β blunts GR activity (149). Concomitant phosphorylation of Ser203 and Ser211 is required for maximal transcriptional activity of GR, whereas phosphorylation of Ser226 and Ser404 reduces transcriptional activity by promoting nuclear export of the receptor (149, 273). Abnormal phosphorylation status of GR has been linked with glucocorticoid resistance in a number of inflammatory diseases (274-276), and maternal asthma is linked to Ser226 phosphorylation in the placenta (198). MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP1) is upregulated by GR and inhibits MAPK expression, and hence reduces inhibitory GR phosphorylation. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) suppressed MKP1 and is thought to antagonize the immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids in RA, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), asthma, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (277, 278).