Primary hypothyroidism is a relatively common endocrine disorder. Because awareness is now high and screening is easy, the condition is detected early in most patients, when symptoms and signs are mild or often non-specific. Patients with more severe hypothyroidism may present with clinical features such as coma, cerebellar ataxia, pericardial effusion, and ascites. These features mimic those of other conditions, and as severe hypothyroidism is uncommon, the condition can be overlooked. We present a case in which the clinical presentation supported by a raised CA 125 concentration led to an incorrect presumptive diagnosis of ovarian malignancy.

Case report

A 74 year old woman presented with increasing abdominal swelling over four months, along with exertional dyspnoea, lethargy, and anorexia. She had been referred by her general practitioner for an urgent surgical outpatient appointment with a provisional diagnosis of intra-abdominal malignancy. However, before her appointment she was admitted as a medical emergency because of worsening breathlessness. She gave no history of thyroid dysfunction, neck surgery, irradiation, or heart disease and was taking no drugs.

On examination she appeared cachectic and pale. She had vitiligo but no lymphadenopathy, signs of chronic liver disease, or goitre. She spoke with a hoarse voice. Her temperature was 36.5°C, pulse 70 beats/min, and blood pressure 140/80 mm Hg. The jugular venous pressure was not raised. She had moderate pitting pedal oedema. The heart sounds were normal with no murmurs. Chest examination showed dull bases and reduced air entry bilaterally. The abdomen was tense with gross ascites but no masses were palpable. Breast and rectal examinations found no abnormality. She was alert and oriented. In view of her age, cachectic appearance, and gross ascites, we suspected an intra-abdominal malignancy.

She had a normal full blood count, urea and electrolyte concentrations, and liver function test results. Her calcium concentration was 2.25 mmol/l (normal range 2.1-2.6 mmol/l), albumin 38 g/l, lactate dehydrogenase 325 U/l (0-500 U/l), and creatinine kinase 95 U/l (0-180 U/l). Chest radiography confirmed bilateral pleural effusions, and her heart was normal size. Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm.

She had a diagnostic and therapeutic paracentesis. The ascitic fluid was found to be an exudate with a protein content of 37 g/l. Cytological analysis showed mesothelial cells and few lymphocytes but no malignant cells. There was no bacterial growth in culture. Repeat paracentesis and cytological analysis on two further samples showed no malignant cells. The tumour marker results showed an extremely high CA 125 concentration of 1059 U/ml (normal < 37 U/ml). Her CA 19-9, CA 15-3, carcinoembryonic antigen, and alpha fetoprotein concentrations were normal.

At this stage, she was reviewed by an oncologist, who thought that the results of the investigations strongly suggested ovarian carcinoma or disseminated peritoneal metastases from an unknown primary tumour. To confirm the diagnosis, she had computed tomography of the abdomen, which showed extensive ascites but no obvious abdominal or pelvic mass. A diagnostic laparoscopy showed no evidence of intraperitoneal malignancy. Mammography and oral gastroduodenoscopy also gave normal results.

Although the patient was not overtly clinically hypothyroid, because she had a hoarse voice and dry skin we tested her thyroid function. The tests showed severe primary hypothyroidism with a serum thyroid stimulating hormone concentration of 73 mU/l (normal range 0.2-5.7 mU/l) and free thyroxine of 5 pmol/l (normal range 9-19 pmol/l). Her thyroid peroxidase antibody titre was 806 IU/ml (normal <50 IU/ml). The patient was started on oral levothyroxine 25 μg a day.

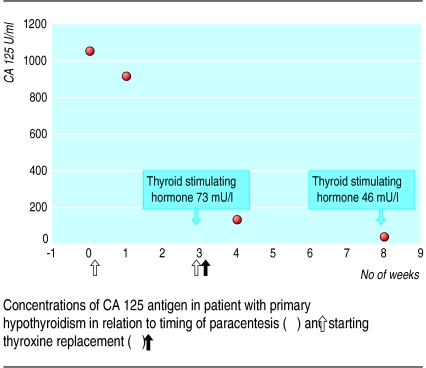

Her CA 125 concentration after the first paracentesis and before starting thyroxine had fallen to 921 U/ml; it fell further to 138 U/ml 10 days after the second paracentesis (figure). After four weeks of thyroxine replacement, her thyroid stimulating hormone concentration was still above normal (46.6 mU/l) and her free thyroxine concentration was 5 pmol/l, but her CA 125 concentration had fallen to 43 U/ml. The thyroxine replacement was increased gradually to 100 μg a day over the subsequent weeks, and she became biochemically and clinically euthyroid with no recurrence of the ascites. She described considerable improvement in her general well being and increased exercise tolerance. She remained well six months after diagnosis, without any evidence of recurrent ascites or malignancy.

Discussion

Ascites is a well known but uncommon feature of hypothyroidism and occurs in about 4% of patients. The typical features of myxoedema ascites include a high ascitic protein concentration (>25 g/l), a high serum to ascites albumin gradient of >11 g/l, presence of glycosaminoglycans (particularly hyaluronic acid), long duration, and rapid resolution of the ascites with thyroxine replacement.1

To our knowledge, this is only the second reported case of myxoedema ascites associated with a raised CA 125 concentration. The previous case was of a 74 year old woman with profound hypothyroidism, severe ascites, and a CA 125 concentration of 684 U/ml.2 She was started on thyroxine replacement, and the ascites resolved and CA 125 concentrations fell towards the reference range as the patient became euthyroid. It was therefore unclear whether the normalisation of the CA 125 concentration was due to resolution of ascites or restoration of euthyroidism.

In contrast, our case clearly shows that CA 125 concentrations fell after therapeutic paracentesis (figure). Although the thyroxine replacement was started one week before we measured CA 125 concentration, we do not think that thyroxine could have significantly contributed to the fall in CA 125 concentration as the patient remained biochemically hypothyroid. Thus, we believe that extremely high CA 125 concentrations in myxoedema ascites are due to peritoneal irritation caused by the presence of ascitic fluid. This is consistent with the observations of Sevinc et al.3 They found that patients with ascites who have benign conditions such as nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis of the liver, tuberculous peritonitis, renal failure, and pancreatitis may have CA 125 concentrations as high as those seen in ovarian carcinoma.3

CA 125 in hypothyroidism

In a study of 131 women, Hashimoto and Matsubara found that the mean CA 125 concentration in hypothyroid women was significantly higher (13.0 (SE 2.6) U/ml; n=49) than in euthyroid (5.5 (0.8) U/ml; n=46) and hyperthyroid women (7.6 (1.1) U/ml; n=36); the P value was <0.02 for both.4 The hypothyroid patients had thyroid stimulating hormone concentrations between 20 mU/l and 200 mU/l, but it was unclear whether any of them had ascites. Unlike the reported cases with myxoedema ascites, these women had only mildly increased CA 125 concentrations.

In summary, our case shows that CA 125 concentrations in patients with hypothyroidism and ascites can be as high as those seen in patients with carcinoma. We therefore suggest that any patient with ascites and a raised CA 125 concentration should have thyroid function measured as part of their initial investigations.

Thyroid function should be checked in all patients with ascites and raised CA 125 concentrations

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.De Castro F, Bonacini M, Walden JM, Schubert TT. Myxoedema ascites. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:411–414. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depczynski B, Ward R, Eisman J. The association between myxoedema ascites and extreme elevation of serum tumour markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4175. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sevinc A, Sari R, Camci C, Buyukberber S. A secondary interpretation is needed on serum CA 125 levels in case of serosal involvement. J R Soc Health. 2000;120:268–270. doi: 10.1177/146642400012000420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto T, Matsubara F. Changes in the tumor marker concentration in female patients with hyper-, eu- and hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Jpn. 1989;36:873–879. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.36.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]