Abstract

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) remains one of the most lethal gynecological cancers. Cytokine-induced memory–like (CIML) natural killer (NK) cells have shown promising results in preclinical and early-phase clinical trials. In the current study, CIML NK cells demonstrated superior antitumor responses against a panel of EOC cell lines, increased expression of activation receptors, and up-regulation of genes involved in cell cycle/proliferation and down-regulation of inhibitory/suppressive genes. CIML NK cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) targeting the membrane-proximal domain of mesothelin (MSLN) further improved the antitumor responses against MSLN-expressing EOC cells and patient-derived xenograft tumor cells. CAR arming of the CIML NK cells subtanstially reduced their dysfunction in patient-derived ascites fluid with transcriptomic changes related to altered metabolism and tonic signaling as potential mechanisms. Lastly, the adoptive transfer of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells demonstrated remarkable inhibition of tumor growth and prevented metastatic spread in xenograft mice, supporting their potential as an effective therapeutic strategy in EOC.

CAR memory–like NK cells targeting the membrane proximal domain of mesothelin demonstrate promising activity in ovarian cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in women with most patients presenting with advanced disease at the time of diagnosis (1). The 5-year survival in all stages is ~50%, which decreases to ~30% for patients with advanced disease (1). The combination of cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy induces remission in ~80% of women, yet most will relapse and succumb to therapy-resistant disease (2, 3). Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized the treatment of hematological and certain solid malignancies (4, 5). Although the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes has been associated with improved progression-free and overall survival in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC) (6, 7), single-agent ICIs and in combination with chemotherapies, antiangiogenic agents and poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase inhibitors have only shown a modest response (8–11). Thus, novel immunotherapeutic strategies are urgently needed to improve survival in EOC.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell immunotherapies have remarkably improved the treatment of hematological malignancies, but their use in solid tumors remains limited. The risk of severe toxicities including cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity, and potential for graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) in an allogenic setting remain major hurdles in CAR T therapy (12, 13). Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic innate lymphocytes that specialize in eliminating virus-infected and malignant cells without any prior antigen sensitization (14, 15). The multiple mechanisms of killing, low risk of CRS, GvHD, and neurotoxicity make NK cells an attractive platform for adoptive cell therapy–based approaches, and their translation in early clinical trials has demonstrated safety and promising preliminary results in multiple cancers. In EOC, the presence of NK cells correlates with improved survival, and a prognostic risk model based on differentially expressed genes of NK cells in EOC samples has recently been reported, further underscoring the importance of NK cell–mediated antitumor activity (16, 17).

Limited ex vivo expansion and viral transduction, poor in vivo persistence, and trafficking after adoptive transfer remain the major challenges to NK cell–based immunotherapy approaches (15). Memory-like differentiation of conventional NK (cNK) cells induced by a brief (12 to 18 hours) activation with the cytokine combination consisting of interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-18, and IL-15, also called cytokine-induced memory-like (CIML or memory-like) NK cells overcomes some of these major hurdles (14, 18–21). CIML NK cells exhibit increased IFN-γ production, reduced threshold for secondary stimuli, massive expansion, and prolonged persistence in the preclinical models and in patients after adoptive transfer (18, 22, 23).

Mesothelin (MSLN) is a glycoprotein overexpressed in multiple malignancies including ~80% of EOCs, particularly in the most common subtype HGSOC (24, 25). MSLN expression has been correlated with chemoresistance, poor prognosis, and increased tumor aggressiveness and has been implicated in promoting tumor invasion and metastasis (26). CAR T cells targeting MSLN have been investigated in preclinical models and clinical settings in MSLN-positive solid tumors (27–31). These trials have demonstrated modest efficacy and a narrow therapeutic window with the use of CAR T cell–based approaches to targeting MSLN in multiple cancer types (27–29, 31).

Herein, we evaluated the antitumor activity of peripheral blood–derived cNK and CIML NK cells against multiple EOC cell lines and generated MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells targeting the membrane-proximal domain of MSLN. MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells showed potent activity against EOC cells and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumor cells. The MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells also exhibited remarkable ability to resist dysfunction in immune-suppressive patient-derived ascites fluid and inhibited tumor growth in an intraperitoneal xenograft mice model. The results from this study support further evaluation of this approach in the clinic and serve as a foundation for developing more effective NK cell–based approaches in the future.

RESULTS

CIML NK cells exhibit superior activity compared to cNK cells against EOC cell lines

Peripheral blood–derived cNK cells were briefly activated with the cytokine combination of IL-12, IL-18, and IL-15 to differentiate into CIML NK cells (Fig. 1A), as described in our previous studies (18–21). After a few days of rest, cytotoxicity and activation status (CD107a expression and IFN-γ production) of CIML and corresponding cNK cells were tested against EOC cell lines including OVCAR8, SKOV3, OVCAR3, CaOV3, and CaOV4. Compared to the cNK, CIML NK cells exhibited consistently higher cytotoxicity, degranulation (CD107a), and IFN-γ responses against these EOC cell lines upon 6 hours of coculture (Fig. 2 and figs. S1 and S2). To investigate the potential underlying mechanisms for the enhanced antitumor responses of CIML NK cells, we performed a detailed surface marker and gene expression profiling using our 14-marker flow cytometry panel (table S1) and bulk RNA sequencing (Fig. 1A). Compared to cNK cells, CIML NK cells showed increased expression of several activating receptors including NKp46, NKp30, NKp44, NKG2D, DNAM1, CD94, and CD69, while only NKG2A and Tim3 inhibitory receptors showed increased expression in the CIML NK cells (Fig. 3A) consistent with previous studies (19, 22, 23).

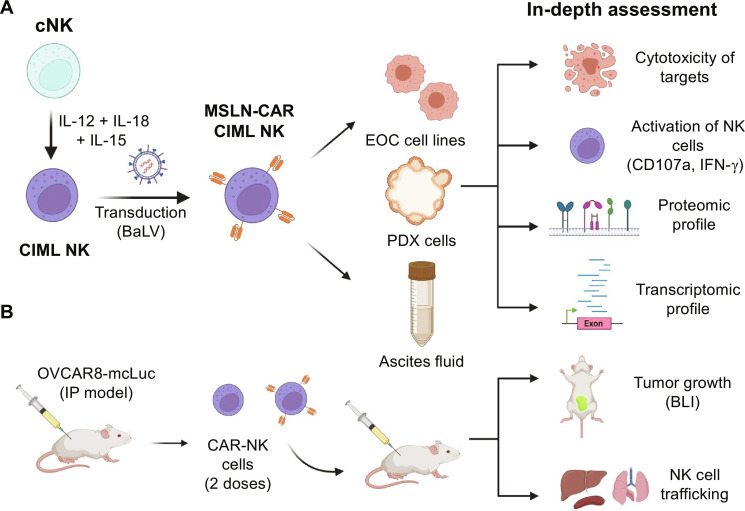

Fig. 1. Overview of the design, development, and in vitro and in vivo evaluation of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells.

(A) CIML NK cells were differentiated from cNK by brief (12 to 18 hours) preactivation with IL-12, IL-18, and IL-15 cytokine combination, further armed with MSLN-CAR using Baboon pseudotyped lentivirus (BaLV)–mediated transduction. The activity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells was then evaluated against EOC cell lines, PDX tumor cells, and after exposure to patient-derived ascites fluid. After exposure, MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells were evaluated for their antitumor cytotoxicity, activation, proteomic, and transcriptomic changes. (B) In vivo therapeutic efficacy assessment of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells in an intraperitoneal (IP) model using OVCAR8 cells in nonobese diabetic scid gamma mice (NSG) mice. The graphics in this figure were created with BioRender.com.

Fig. 2. CIML NK cells exhibit superior activity against a panel of EOC cell lines.

(A) Schematic diagram showing the generation of CIML NK cells from cNK cells by 12- to 18-hour activation with the specific cytokine cocktail, 4 to 5 days’ rest and their assessment for cytotoxicity (annexin V/7-AAD), degranulation (CD107a), and IFN-γ production upon 6-hour coculture with EOC cell lines (OVCAR8, SKOV3, OVCAR3, CaOV3, and CaOV4). The graphics were created with BioRender.com. (B) Cytotoxicity of CIML NK cells (purple) versus cNK cells (green) upon coculture with various EOC cell lines at various E:T ratios. (C) Summary of the relative cytotoxicity of CIML NK versus cNK cells at 2:1 E:T ratio. (D) Degranulation (CD107a) and (E) IFN-γ production of CIML NK cells (purple) versus cNK cells (green) upon coculture with various EOC cell lines at 2:1 E:T ratio. Data are represented as means ± SD. Data in (B), (D), and (E) are from NK cells from three independent healthy donors in two technical replicates. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with donor-matched Sidak’s (B) or Tukey’s [(D) and (E)] multiple comparisons was performed between different groups to determine the statistical difference; ***P ≤ 0.0001, ***P ≤ 0.001, **P ≤ 0.01, and *P ≤ 0.05.

Fig. 3. Proteomic and gene expression differences in the cNK versus CIML NK cells at baseline and gene expression changes in the EOC cells upon coculture with CIML NK cells.

(A) Heatmap showing the expression of key receptors in cNK versus CIML NK cells (three donors) as assessed by an extended flow cytometry NK cell panel. (B) Heatmap (B1) and STRING analysis (B2) of differentially expressed genes in cNK and CIML NK cells (two donors) evaluated by bulk RNA sequencing. (C to E) Volcano plots depicting the differentially expressed genes in EOC cell lines; OVCAR8 (C1), SKOV3 (D1), and OVCAR3 (E1) flow-sorted after 24-hour coculture with CIML NK cells (two donors) at 1:4 E:T ratio. Heatmaps (C2, D2, and E2) and STRING analysis (C3, D3, and E3) of selected genes in EOC cells after coculture with CIML NK cells. Bulk RNA sequencing was performed on flow-sorted EOC cell lines, and data are represented with FDR setup (0.05) and fold change (2).

Gene expression analysis identified cell cycle control, cell division, and migration as the gene set up-regulated in CIML NK compared with cNK cells. Specifically, CCNB2, CENPE, and ASPM (32–34) were found among the top up-regulated genes [after false discovery rate (FDR) setup of ≤0.05 and fold change of ≥2 or ≤−2] (Fig. 3B, 1, 2, 3). These results are consistent with the increased proliferation observed in CIML NK cells. The group of down-regulated genes included inhibitory/suppressive genes (e.g., VSIG4 and LILRB5) (35, 36) further highlighting the increased global activation status of CIML NK cells that likely contributes to their higher antitumor activity. We also found increased expression of genes involved in heme synthesis (HBG2, ALAS2, HBE1, and HBB) (37, 38) in CIML NK cells, the significance of which needs further validation in additional donors and exploration through proteomic analysis. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for up-regulated genes showed significant enrichment of PLK1, cell cycle, E2F targets, G2-M checkpoints, and heme metabolism pathways (fig. S3, B and C). In addition, we used the new dictionary published by Cui et al. (39) to perform immune response enrichment analysis (IREA) of up-regulated and down-regulated genes (FDR setup of ≤0.05 and fold change of ≥2 or ≤−2) (fig. S4). The enrichment score from the up-regulated genes showed enrichment of responses to IL-18, IL-2, IL-15, and IL4 cytokines. The enrichment score from the down-regulated genes had similar cytokine gene expression signatures except for the addition of IL-12 cytokine.

Despite their overall enhanced activity, there was heterogeneity in the responses of different EOC cell lines to CIML NK cells. As evident in Fig. 2C, OVCAR8 and OVCAR3 cells exhibited higher susceptibility to CIML NK cells compared with SKOV3 cells. To investigate the potential mechanism(s) underlying this heterogeneity, we assessed gene expression changes in CIML NK cells after being exposed to each EOC cell line for 24 hours. Changes in gene expression in CIML NK cells was similar following exposure to any of the EOC cell lines tested (OVCAR8, OVCAR3, or SKOV3) (fig. S5), suggesting that the differences in relative cytotoxicity of CIML NK cells toward these EOC cells could be due to tumor cell–intrinsic gene expression or ligand expression profiles mediating their susceptibility/resistance (40). To test this hypothesis, we assessed the gene expression of the flow-sorted EOC cells after coculture with CIML NK cells. We found unique gene expression patterns in SKOV3 cells (relatively resistant cell line) when compared to OVCAR3 and OVCAR8 cells after coculture with CIML NK cells (Fig. 3, C to E). The up-regulated genes in SKOV3 after exposure to CIML NK cells could be attributed to treatment resistance and dysfunction of immune cells (ATF4, SLC3A2, CARS1, YARS1, and MUC16) (41–43), whereas very few IFN response genes were up-regulated (IRF9 and APOL6) (44) in the SKOV3 cell line (compared to the other cell lines tested). Among the up-regulated genes, we found several genes in common with the ferroptosis-related gene group (CARS1 and CHAC1) (45, 46), indicating that the ferroptosis pathway may contribute to resistance to the CIML NK cells in this cell line. In sharp contrast, among the top up-regulated genes in OVCAR8 and OVCAR3 cells after exposure to CIML NK cells were interferon-stimulated genes (IRF1, IRF9, STAT1, TAP, and PSMB) (47) (Fig. 3, D and E), consistent with the cells undergoing cell apoptosis in response to the CIML NK cells.

As we observed increased expression of key activation receptors in CIML NK cells (Fig. 3A), we further explored the gene expression of ligands in the tumor cells that could potentially, with the corresponding activating or inhibitory receptors on NK cells. These include B7-H6 (NKp30), MICA/B (NKG2D), CD155 (DNAM1/TIGIT), HLA-E (CD94/NKG2A), CDH1/2 (KLRG1), and Galectin-9 (Tim3) (fig. S6). Since the SKOV3 cell line used in our study was the most resistant cell line, we compared the gene expression of the abovementioned ligands in SKOV3 to the more susceptible cell lines, OVCAR8 and OVCAR3. We observed lower expression of NCR3 (gene for B7-H6), MICB, and CDH2 in SKOV3 when compared to OVCAR8 and also a lower expression of MICB when compared to OVCAR3 (fig. S6). These findings could potentially explain the lack of susceptibility of SKOV3 cell line to the NK cell–mediated killing. However, other interesting gene expression differences including decreased LGALS9 (TIM-3 ligand) in the SKOV3 compared to other the other cell lines was observed, which underscores the complexity of receptor/ligand interactions between NK and tumor cells. Together, the gene expression and ligand analysis provide clues toward the potential mechanisms of relative resistance and susceptibility of different cancer cells toward NK cells.

Arming of CIML NK cells with a CAR targeting the membrane-proximal domain of MSLN significantly enhances antitumor responses against multiple EOC cell lines

MSLN is highly expressed in EOC, especially in the most common subtype of EOC (25). Recent studies have demonstrated that MSLN undergoes proteolytic cleavage leading to its shedding by cancer cells, and CAR T cells targeting the membrane-proximal domain have shown improved activity compared to the CAR targeting membrane-distal domain against MSLN-positive cells (48–50). Inspired by these findings, we designed and tested CAR NK cells targeting the proximal domain of MSLN (Fig. 1B). Our CAR construct consisted of scFv targeting the membrane-proximal domain [based on the YP218 clone (50)], CD8 hinge region, and transmembrane region and with 4-1BB and CD3ζ intracellular domains. We also included a self-cleaving P2A sequence followed by enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (Fig. 4A). CIML NK cells were transduced 1 day after initial preactivation with IL-12, IL-18, and IL-15 using lentivirus pseudotyped with baboon endogenous retroviral envelop glycoprotein (shortened as baboon lentivirus or BaLV) as described in our previous study (51). The average transduction efficiency in CIML NK cells at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5 to 1.0 (assessed by GFP+ cells) was 42.1 ± 10.8% (Fig. 4B) and was stable over the course of several weeks.

Fig. 4. Generation and in vitro assessment of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells.

(A) Schematic representation of the CAR construct design and use of BaLV to transduce CIML NK cells. The graphics were created with BioRender.com. (B) Transduced CIML NK cells stably expressed the CAR construct as assessed by GFP expression on days 5 and 10 after transduction (six donors). (C) Experimental design assessing in vitro antitumor activity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells against EOC cell lines (OVCAR8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3). (D) Degranulation (CD107a) and IFN-γ production in untransduced (purple) and MSLN-CAR (orange) CIML NK cells after 6-hour coculture with the EOC cell lines at a 2:1 E:T ratio. (E) Cytotoxicity following long-term (48 hours) coculture of untransduced (purple) versus MSLN-CAR (orange) CIML NK cells with EOC cell lines at various E:T ratios. Data are represented as means ± SD. Data from (D) and (E) show results using NK cells from three independent donors. Two-way ANOVA with donor-matched Tukey’s multiple comparison was performed between different groups to determine the statistical difference; **P ≤ 0.01, and *P ≤ 0.05.

We then tested the antitumor activity of MSLN-CAR in comparison to untransduced CIML NK cells (Fig. 4C). MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells showed significantly enhanced CD107a expression and IFN-γ production against multiple EOC cell lines, including OVCAR8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3, following coculture for 6 hours (Fig. 4D). We next tested the long-term (48- and 96-hour coculture) cytotoxicity of MSLN-CAR compared to untransduced CIML NK cells (Fig. 4E). We observed consistently increased cytotoxicity in the EOC cells when cocultured with MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells compared to the untransduced CIML NK cells (Fig. 4E and fig. S7), demonstrating the ability of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells to maintain their cytotoxicity upon long-term exposure to target cells. This is important in view of a recent study demonstrating rapid induction of exhaustion in T cells upon exposure to targets (52).

We also compared the antitumor responses of CIML NK cells armed with the CAR constructs targeting membrane proximal versus distal [based on SS1P clone (49)] domains of the MSLN protein. Consistent with the previous CAR T cell study (49), the CAR targeting the proximal domain exhibited increased CD107a expression, IFN-γ production, and cytotoxicity against EOC cell lines (fig. S8). The specificity of the MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells was further evaluated by assessing their cytotoxicity against SKOV3 (MSLN+), Panc1 (MSLN-), and K562 (MSLN-) cells compared to the same donor untransduced CIML NK cells and irrelevant CAR (CD19-CAR) CIML NK cells. More robust cytotoxicity was observed against MSLN+ SKOV3 cells when exposed to MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells compared to the untransduced and CD19-CAR CIML NK cells (fig. S9). In addition, there were no significant differences in the cell cytotoxicity against Panc1 and K562 cells when treated with either MSLN-CAR or CD19-CAR CIML NK cells. Together, these data demonstrate that the antitumor activity of the MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells against MSLN expressing tumor cells is CAR mediated.

In addition, we compared CAR cNK to the CAR CIML NK cells using three key parameters: 1) transduction efficiency, 2) proliferation, and 3) antitumor responses against EOC cells (fig. S10). CIML NK cells showed significantly higher transduction efficiency at much lower MOI compared to the cNK cells (fig. S10B) consistent with our previous study (51). Furthermore, CAR-CIML NK cells after transduction exhibited significantly higher expansion/proliferation compared to the CAR-cNK cells (fig. S10C). The cytotoxicity of both MSLN-CAR cNK and MSLN-CAR CIML NK was higher against all the EOC cell lines tested (fig. S10D) with no major differences between CAR cNK and CAR CIML NK cells (fig. S10E).

To characterize major gene expression changes in the CIML NK cell upon transduction with the CAR construct, we performed bulk RNA sequencing of the same donor CIML NK cells before and after transduction. MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells exhibited increased expression of HLA class II genes, MX1, DMD, UBD, and CCL7 compared to untransduced CIML NK cells (fig. S11). In addition, IREA enrichment of top differentially expressed genes identified enrichment of cytokines primarily associated with IFN signaling and, to a lesser extent, with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-23, and IL-27 (fig. S11B). These findings are similar to those found in CAR T cells with 4-1BB and CD3ζ as costimulatory domains (53).

MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells demonstrate superior antitumor activity in PDX explants and patient-derived ascitic fluid

PDX models have similar pathophysiological and genetic characteristics to the parental tumor and are often used to test the activity of novel immunotherapy platforms (54, 55). Three independent PDX models [labeled as DF86, DF68, and DF59 (56), fig. S12A] were used in this study to assess the cytotoxicity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells. Two (DF86 and DF68) of the three PDX models had high MSLN expression, whereas DF59 showed minimal MSLN expression (Fig. 5B). The PDX tumor cells formed three-dimensional (3D) spheroids and therefore were a more realistic model to test the efficacy of our CAR-NK cells ex vivo. To assess cytotoxicity, the PDX tumor cells were cultured with the same donor untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells for 24 or 48 hours. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by gating on the EpCAM+ cells and apoptosis markers (fig. S12B). MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells showed significantly increased cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production against MSLN expressing PDX tumor cells (from DF86 and DF68) compared to the untransduced CIML NK cells (Fig. 5C and fig. S12, C and D). In contrast, no significant differences in the cytotoxicity were observed in MSLN low PDX tumor cells (model DF59) between MSLN-CAR CIML versus untransduced CIML NK cells with only a slight increase in the IFN-γ production (Fig. 5, C and D, and fig. S12D).

Fig. 5. Assessment of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cell activity against PDX tumor cells.

(A) Schematic representation of PDX cytotoxicity upon coculture with untransduced versus MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells. The graphics were created with BioRender.com. (B) MSLN expression (pink) in the PDX cells from the three models in comparison with isotype (gray). (C) Representative flow plots showing the EpCAM+ apoptotic PDX cells upon coculture with CIML or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells. (D) Cytotoxicity of untransduced (purple) versus MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (orange) against the PDX cells after 48-hour coculture at E:T ratios of 5:1 and 10:1. Data are represented as means ± SD. Data in (B) are from five independent healthy NK cell donors. Two-way ANOVA with donor-matched Sidak’s multiple comparison was performed between different groups to determine the statistical difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001.

One of the major challenges in the clinical translation of adoptive immune therapy to treat solid tumors has been retaining their potency and persistent functionality in an immune-suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) (57). Pathological accumulation of ascites, composed of cellular and acellular components, in the peritoneal cavity is a hallmark of EOC, occurring in one-third of the newly diagnosed patients and almost all relapsed cases (58, 59). Cellular components and secreted soluble factors in malignant ascites from patients with EOC can modulate the tumor cells as well as the activity of local immune cells, overall promoting an immunosuppressive microenvironment (60). Thus, we sought to test the function of our MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells in the presence of ascites fluid from patients with EOC. We first analyzed the major soluble proteins in ascitic fluid collected from patients with EOC undergoing paracentesis (Fig. 6). The major soluble proteins (using 48-plex discovery assay) in the ascites fluid were found to be IL-6, IP-10, MCP-1, granulocyte CSF (G-CSF), and IL-10, which are known to modulate immune cells, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), which are known to regulate angiogenesis, and CCL2, CCL5, CXCL8, and CXCL9, which are known to recruit suppressive immune cells (Fig. 6B and fig. S13). The presence of these cytokines/chemokines is consistent with the previously reported studies in ascites (59, 61–64).

Fig. 6. Phenotypic, gene expression, and IFN-γ production changes in MSLN-CAR CIML versus untransduced CIML NK cells after exposure to immune-suppressive patient-derived ascites fluid.

(A) Schematic diagram of the study design for the functional assessment of NK cells including IFN-γ secretion, in-depth phenotype, and transcriptomic profile after exposure to EOC patient–derived ascites fluid exposure. The graphics were created with BioRender.com. (B) Cytokine/chemokine analysis of ascites fluid from six different patients with EOC using a 48-marker multiplex panel. (C) IFN-γ production by untransduced (purple) or MSLN-CAR (orange) CIML NK cells after exposure to ascites fluid for 48 hours (checkered pattern) upon coculture with OVCAR8 and SKOV3 target cells for 24 hours at 2:1 E:T ratio and assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data expressed as fold change of IFN-γ produced from NK cells exposed to ascites versus cells not exposed to ascites. (D) Fold changes in the expression of key activating and inhibitory receptors in untransduced (purple) and MSLN-CAR (orange) CIML NK cells after exposure to ascitic fluid. Data expressed as fold change with the marker expression without ascites fluid normalized to 1.0 (dotted line). (E) Heatmap and STRING analysis of top 20 differentially expressed genes in untransduced and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells with and without ascitic fluid exposure. Data are represented as means ± SD. Data from (C) and (D) show results using NK cells from three to four independent donors paired with the ascites fluid from three to four patients with EOC, and data from (E) show results from two independent donors paired with ascites fluid from two patients with EOC. Two-way ANOVA with donor-matched Tukey’s multiple comparisons was performed between different groups to determine the statistical difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001, ***P ≤ 0.001, and **P ≤ 0.01.

Next, the antitumor responses (evaluated by IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity) of untransduced and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells were evaluated following incubation with ascites fluid for 48 hours followed by coculture with the EOC cell lines (Fig. 6A). MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells maintained antitumor activity even after being exposed to ascites fluid for up to 48 hours. In contrast, a significant suppression in the antitumor responses of the untransduced CIML NK cells was detected (Fig. 6C and fig. S14). To better understand potential mechanisms for these differences, we performed extended surface marker and gene expression profiling of the untransduced and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells before and after exposure to the ascites fluid. Expression levels of NKp46, NKG2D, and NKp44 were decreased in CIML NK cells exposed to ascitic fluid but were maintained in the MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (Fig. 6D). In addition, expression of the inhibitory receptor KLRG1 was increased in untransduced CIML NK cells following exposure to ascites. Together, these data suggest that CIML NK cells acquire an “inhibitory or dysfunctional” phenotype upon exposure to the ascitic fluid, but MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells are able to resist this change, potentially explaining the differences in their function. The expression of NKp30 was decreased the most in MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells upon exposure to ascites, which may have implications for the CAR CIML NK cells in tumors with high expression of B7-H6, a known ligand for NKp30 (65, 66).

Major differences in the gene expression profile were also observed in untransduced versus MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells upon exposure to the ascites (Fig. 6E). In the untransduced CIML NK cells, the up-regulated genes included those related to membrane repair, differentiation, and apoptosis/cell-cycle arrest (PLS3, MYOF, IFI27, PRUNE2, and NT5E) (67–70); genes involved in impaired glucose metabolism and/or altered metabolism (CPXM1, YAP1, and ASS1) (71, 72); and genes associated with other immune checkpoints and exhaustion including TSKU (transforming growth factor–β signaling), FN1 (corelated with immune checkpoints), AREG, and COL1A1 (corelated with immune suppression) (73–75). On the contrary, MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells showed changes in the expression of several genes that are involved in “metabolic adaptation” (Fig. 6E), such as up-regulation of CREB3L3, a gene involved in the adaptation to energy starvation that triggers lipid droplet formation (76). In addition, the observed down-regulation of FMC1-LUC7L2 is potentially related to a metabolic shift from glycolysis to OXPHOS that allows cell survival in low glucose conditions (77). The expression of lipid metabolism genes (FADS2, SIPR5, and SCD) (78–80) was decreased in the MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells upon exposure to ascites. The down-regulation of FOS-related genes was the only common change detected between the untransduced CIML and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells after exposure to ascitic fluid. These results suggest that the expression of MSLN-CAR in CIML NK cells alters the cellular metabolic state of the cells.

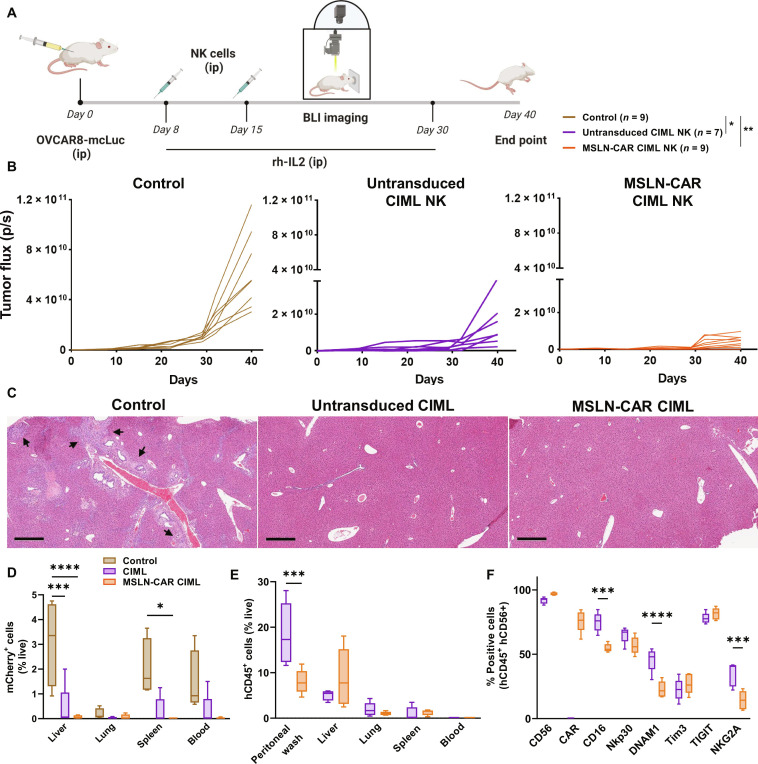

MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells exhibit enhanced tumor control and prevent metastatic spread in a preclinical xenograft model

Peritoneal dissemination is the most common form of malignant progression observed in EOC with ~70% of patients with EOC presenting with peritoneal carcinomatosis at the time of diagnosis (81, 82). To mimic this clinical scenario in a preclinical mouse model, we evaluated MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells in nonobese diabetic (NOD) scid gamma mice (NSG) mice that were intraperitoneally (ip) implanted with human EOC cells (Fig. 7). One week after the intraperitoneal injection of OVCAR8 transduced to express Luciferase and mCherry (OVCAR8-mcLuc, ) cells 1 × 106 cells), mice were randomly divided into three groups to receive either: control [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), no NK cells], untransduced CIML NK cells, or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells. Two doses of the NK cells were injected (5 × 106, ip) 1 and 2 weeks after initial cancer cell implantation. The NK cells were supported by rh-IL2 (intraperitoneal), and bioluminescence (BLI) was used to monitor the tumor growth once a week for 40 days (Fig. 7A and fig. S15A). Overall, there was significant inhibition of tumor growth and increased survival in mice that received CIML NK and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells compared to the control group (Fig. 7B and fig. S15B). Furthermore, hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver sections revealed metastatic tumor cell deposits in control mice but not in the mice that received untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (Fig. 7C). Quantification of the tumor spread by measuring the tumor cells in homogenized organs showed significantly higher levels of mCherry+ tumor cells in the liver and spleen of control mice compared to the mice treated with MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (P < 0.0001) and untransduced CIML NK cells (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7D). In addition, no ascites fluid accumulation was observed in the NK cell treatment groups, whereas, on average, 1033 ± 873.7 μl per mouse of ascites fluid was observed in the control group (three of five mice) at the time of study end point (fig. S17A). The persistence of NK cells in the different organs was also evaluated at the end point where NK cells were detected in the liver, lungs, and tumor (figs. S16 and S17B). These results show that MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells are effective in controlling tumor burden in the peritoneum, and tumor metastatic spread into other organs in our xenograft mouse model.

Fig. 7. MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells exhibit tumor inhibition and prevent tumor cell dissemination in a preclinical xenograft mouse model.

(A) Schematic representation of the therapeutic regimen; NSG mice received OVCAR8-mcLuc (1× 106, ip) followed by PBS (control), untransduced CIML versus MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (5 × 106, ip) on days 8 and 15 after OVCAR8-mcLuc implantation. Mice were given 75,000 U of recombinant human IL-2 intraperitoneally every other day (to support adoptively transferred NK cells), and tumor burden was assessed by BLI. The graphics were created with BioRender.com. (B) Comparison of tumor burden in mice receiving PBS control (brown), untransduced CIML NK cells (purple), and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (orange) and statistical significance shown in (A). (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the liver sections showing the tumor micro-metastasis (shown by arrows) in PBS control versus the treatment groups (scale bar, 200 μm). (D) Comparison of tumor cell spread assessed by flow cytometry of mCherry+ tumor cells in peripheral blood and key organs (lungs, liver, and spleen). (E) Trafficking of the adoptively transferred untransduced CIML and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells into key organs as assessed by flow cytometry of hCD45+ cells 1 week after adoptive transfer (5 × 106 cells, ip). (F) Expression of key markers in adoptively transferred untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells in the peritoneal fluid from the mice in (E). Data are represented as means ± SD. Data in (C) show results compiled from two independent experiments with NK cells from two different donors. Data in (D) are from n = 4 to 5 mice per group. Data in (E) and (F) are from an independent experiment with n = 5 mice per group. Two-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison was performed between different groups to determine the statistical difference; ****P ≤ 0.0001, ***P ≤ 0.001, **P ≤ 0.01, *P ≤ 0.05.

To evaluate the phenotype of adoptively transferred CIML and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells that are able to traffic to the major organs in these mice, we used a separate cohort of mice that received a single dose of untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (5 × 106, ip) and collected the organs 1 week after the adoptive transfer. NK cells (detected on the basis of hCD45+ cells among live cells from homogenized organs) were detected in relatively high numbers in the peritoneal washings, liver, and, to a lesser extent, in the lungs and spleen (Fig. 7E). Phenotypic analysis of NK cells revealed persistent CAR expression in the MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells in both the peritoneal fluid and the liver. Decreased expression of CD16 (both liver and peritoneal washings), DNAM1, and NKG2A (only in peritoneal fluid) was observed on MSLN-CAR compared to untransduced CIML NK cells. CD56 expression was decreased (only in liver) on CIML NK cells compared to MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells (Fig. 7F and fig. S18). Expression of other key receptors including NKp30, TIM3, and TIGIT was similar in both population of NK these cells in both tested sites.

DISCUSSION

EOC remains the most lethal of the gynecological malignancies and therefore a major unmet need. To date, ICIs have not demonstrated therapeutic efficacy as single agents in this disease, and novel strategies to induce potent antitumor immune responses are needed to improve survival rates in these patients. Immunotherapeutic approaches including the use of CAR-T cells have revolutionized our approach to multiple cancer types; however, a narrow therapeutic window and major adverse effects including severe CRS, neurotoxicity, and risk of GvHD with the use of allogeneic products remain as some of the major hurdles (13, 83). Here, we demonstrate the promising activity of memory-like NK cells, a differentiation state induced by brief cytokine activation, against multiple EOC cell lines. Further, their activity was significantly improved upon arming with a novel CAR construct targeting the membrane-proximal domain of MSLN, which is widely expressed in several malignancies including EOC. We also demonstrate not only their potent antitumor activity but also characterized gene expression changes in both the effector and target cell side and after exposure to immune-suppressive ascitic fluid from patients with EOC. We identified novel actionable genes potentially contributing to CIML NK cell resistance, which will guide our future efforts to further improve CAR NK–based approaches. Furthermore, favorable tumor control was seen in PDX cells ex vivo and xenograft mouse model in vivo supporting the translation of this approach to the clinic.

Enhanced cytotoxicity, degranulation, and IFN-γ production of CIML NK cells against a panel of EOC cell lines observed in our study are consistent with a prior study showing CIML NK cell activity against SKOV3 cell line (84). The enhanced CIML NK cell activity against a heterogenous panel of EOC cell lines demonstrates the broad applicability of the CIML NK cell–based therapeutic approach in EOC patients with different pathology and underlying genetic makeup. Our in-depth surface marker gene expression and GSEA analysis comparison between CIML and cNK cells revealed increased expression of multiple surface proteins including NKp46, NKp30, NKp44, NKG2D, DNAM1, CD94, and CD69, gene expression of cell cycle/division genes (CCNB2, CENPE, and ASPM), and decreased expression of inhibitory genes (VSIG4 and LILRB5). We also performed IREA analysis and observed that the gene signature of CIML NK cells overlaps with that of IL-18, IL-15, IL-12, and IL-2 cytokines. This cell surface protein and gene expression could potentially contribute to the enhanced antitumor responses of CIML NK cells against a variety of tumor types including acute myeloid leukemia, ovarian, melanoma, and head and neck cancer seen in previous studies (19, 84–86). The expression of genes involved in heme synthesis was induced in CIML NK cells. As heme is critical for energy and iron metabolism, enhanced heme synthesis may partly underlie the enhanced antitumor activity of CIML NK cells which needs further exploration.

However, not all cancer cells are equally susceptible to CIML NK cells as highlighted by relative resistance observed in the SKOV3 cell line. Upon coculture with CIML NK cells, SKOV3 cells up-regulated genes attributed to immune cell dysfunction (ATF4, SLC3A2, CARS1, YARS1, and MUC16), which may explain the intrinsic resistance mechanism in these tumor cells. Similarly, induction of ferroptosis-related genes could also contribute to NK cell killing as a correlation between a group of ferroptosis-related genes and immune checkpoint receptors contributing toward immune suppression has recently been reported (45, 46, 87). These gene expression changes upon NK cell coculture combined with baseline gene expression of key ligands in the tumor cells provided potential clues about their relative susceptibility and resistance to the CIML NK cells.

The use of BaLV that interacts with ASCT1 or ASCT2 allows high transduction efficiency in NK cells (88, 89), and we have previously demonstrated that this is further enhanced by the CIML NK cell differentiation due to the increased expression of ASTC2 with CIML activation (51). Increased transduction efficiency (particularly at lower MOIs) and expansion of the transduced CIML NK cells seen in our study favored them over cNK cells and therefore CIML NK cells were used for further evaluation in our study. Here, we used a CAR targeting the membrane-proximal domain of MSLN. MSLN is a complex glycoprotein and is a well-studied target as it is highly expressed in multiple cancer types including EOC (24). Fully processed, mature MSLN protein contains 302 amino acid residues, and various antibodies have been developed to target different regions of the protein (90). MSLN undergoes proteolytic cleavage in cancer cells, and recent studies targeting its membrane-proximal domain with the CAR T cells demonstrated improved antitumor responses (48, 49). Our results extend these studies to support the use of the CAR constructs targeting the membrane-proximal domain of MSLN in the NK cell context (49, 90). Given the heterogeneous nature of EOC, the potent activity of the CIML NK and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells against a panel of EOC cell lines demonstrates the broad applicability of the CIML NK cell–based therapeutic approach in EOC patients with different genetic and molecular profiles. The specificity and enhanced activity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells was further exemplified when tested against PDX, wherein increased cytotoxicity was selectively observed against MSLN expressing PDX cells.

It has been previously reported that NK cell function is hindered after their exposure to ascitic fluid (60). We observed similar inhibition in CIML NK cells (phenotype and IFN-γ production) after exposure to ascites fluid, whereas MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells maintained antitumor activity at the same ascitic fluid conditions. In-depth gene analysis of untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells after exposure to ascites fluid suggested that MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells maintained a metabolically adaptive state, whereas the untransduced NK showed metabolic impairment. The tonic signaling in the CAR could potentially be responsible for this resistance to immune suppression; however, this requires further detailed study. The potent tumor control observed in xenograft mice with intraperitoneal tumor cells is particularly promising as the vast majority (~70%) of patients with EOC present with peritoneal dissemination at the time of diagnosis, decreasing the therapeutic success in these patients (81, 82). While the intravenous route of effector cell delivery including NK cells is optimal because of the intraperitoneal spread seen in patients with EOC and the relative ease of the intraperitoneal delivery, we chose this route for the delivery of our MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells. In a previous study, improved tumor control was observed in the EOC model using untransduced CIML NK cells (84). Here, we show not only that tumor control by the CIML NK cells is significantly improved upon arming with an MSLN targeting CAR in the peritoneum but that it also prevents metastatic spread. Furthermore, our findings that CIML NK and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells’ traffic to other major organs from the peritoneum site could explain their ability to prevent metastatic spread.

While overall very promising, our approach has several potential limitations that can/need to be addressed with future endeavors. Therapy failure of adoptive cell therapies in hematological malignancies could be attributed to antigen loss and immune cell exhaustion (91). Although we have shown in vitro and in vivo that the adoptive MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells are functional and can resist the immune-suppressive microenvironment, antigen loss may still be a concern (92). Although NK cells have multiple mechanisms of cytotoxicity and target killing that could compensate for the antigen loss, this needs to be investigated in future studies. Another major drawback of the adoptive cell therapy approaches (both NK and T cells) has been the poor infiltration of these effector immune cells to the tumor site, especially in solid tumors (15). We developed the preclinical xenograft model used in this study to mimic the peritoneal dissemination seen in most patients with advanced EOC and thus mitigating a need for the MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells to traffic to the tumor site from the blood. For other solid tumors with nonperitoneal location/metastatic spread, novel approaches including recent studies overexpressing tumor-homing receptors may potentially help overcome this major hurdle and need further exploration (15). Poor effector cell function in the TME remains another major barrier to immunotherapy approaches (15). Our data demonstrating persistent antitumor cytotoxicity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells even after prolonged ascites fluid exposure are promising and could translate to improved tumor control in EOC patients with peritoneal spread of the disease.

In summary, our study supports the evaluation of the CIML NK cell CAR-based approaches in patients with advanced ovarian cancer and provides clues to potentially actionable mechanisms of immune escape in these patients. Furthermore, the novel biology of CIML NK cells including their ability to mediate robust antitumor responses even in a harsh TME makes them particularly attractive for further evaluation in other advanced solid tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cytokines used in this study are as follows: IL-12 (219-IL-005/CF, R&D), IL-18 (9124-IL-010/CF, R&D), IL-15 (130-095-762, Miltenyi), and IL-2 (130-097-746, Miltenyi). The media and serums are the following: RPMI 1640 (11875-119), NK magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) medium (130-114-429), penicillin-streptomycin (15140-122), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10082-147), human serum (H3667), and l-glutamine (25030081). The following antibodies were used: HA.11-APC (allophycocyanin, 16B12), CellTrace Violet (CTV, C34557), Live/dead dye (Violet, L34964), annexin V phycoerythrin (PE) (640947), 7AAD (51-68981E), IFN-γ PE-Cy7 (557643), tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (552889), CD107a APC (H4A3), CD3 BV510 (HIT3a), CD16 APC-Cy7 (3G8), cell counting kit-8 (WST-8, ab228554), IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (ab236895), Apotracker (BioLegend), mCD45-PE (30-F11), hCD45-APC (HI30), CD56-PE-Cy7 (HCD56), and EpCAM-PE or APC (9C4).

EOC cell lines

Various EOC cell lines used in this study (OVCAR8, SKOV3, OVCAR3, CaOV3, and CaOV4) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection.

Generation of CIML NK cells

NK cells were isolated from healthy donor leukapheresis collars (Crimson core, ID T0197) via Ficoll-Paque density gradient using RosetteSep human NK cell enrichment kit (Stemcell Technologies). Purified NK cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and Hepes in the presence of low dose IL-15 (1 to 2 ng/ml) referred to as cNK cells. To generate CIML NK cells, cNK cells after purification were preactivated with IL-12 (10 ng/ml), IL-18 (50 ng/ml), and IL-15 (50 ng/ml) for 12 to 18 hours. The cells were then washed twice to remove the cytokines and rested in media with low-dose IL-15 (1 to 2 ng/ml) for 4 to 5 days before further assessment. Media and IL-15 were replaced every other day.

Cytotoxicity, CD107a, and IFN-γ analysis of NK cells

As EOC is a heterogenous cancer, a panel of cell lines was used, which included OVCAR8 (low-grade serous); SKOV3 (clear cell); and OVCAR3, CaOV3, and CaOV4 (high-grade serous) (93). All the EOC cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For cytotoxicity assays, the EOC cells were stained with CTV (Molecular probes), plated in a 96-well flat-bottom plate (25,000 cells per well), and allowed to adhere for approximately 18 hours. NK cells were added to the cancer cells at E:T ratios of 1:1, 2:1, 5:1, and 10:1 and cocultured for 6 hours. After coculture, the apoptotic cells were evaluated in CTV+ EOC cells using flow cytometry by annexin V/7-AAD staining, and data are reported as percentage apoptotic cells (annexin V+ 7-AAD+).

To evaluate degranulation (CD107a) and IFN-γ production, NK cells were cocultured with EOC cells as described for cytotoxicity. GolgiPlug and GolgiStop (Brefeldin A and Monensin, BD Biosciences) were added after 1 hour of coculture and then further incubated for 5 hours. Cells were then collected and stained for 30 mins on ice for extracellular surface proteins (CD56-PE, CD3-BV510, CD107a-APC, and CD16-APC-Cy7, all from BioLegend) as well as live/dead dye. The cells were washed once with staining buffer before fixation (BD Cytofix/perm). After fixation, cells were washed twice with Perm wash (1X), and intracellular staining was performed (IFN-γ–PE Cy7, BioLegend) for 30 mins on ice and then washed once with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer and acquired using BD LSR Fortessa Cell Analyzer. Data were reported as percentage of CD107a and IFN-γ–positive NK cells calculated by gating on CD56+ CD3- NK cells.

Cell surface marker and gene expression analyses of NK cells and EOC cells

The following activating and inhibitory receptors on NK cells—CD56-PE, CD16-AF700, NKp30-PE Dazzle, NKp44-PECy7, NKp46-FITC, DNAM1-BV785, KLRG1-PE Dazzle, NKG2D-APC, NKG2A-AF700, SIGLEC7-APC, CD39-BV711, CD94-FITC, CD69-APC Cy7, TIGIT-BV510, and Tim3-BV605—were analyzed using flow cytometry (table S1). For the gene expression analysis, cNK or CIML were cocultured with OVCAR8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3 at the ratio of 2:1 (for NK cell gene expression analysis) or 1:4 (for cancer cell gene expression analysis) in separate experiments. After coculture, the cells were collected via flow-assisted sorting, and dry pellets were frozen at −80°C. Bulk RNA sequencing analysis was performed by MedGenome Inc. (California, USA) and analyzed using Partek Flow Genomic analysis software. Gene expression analysis was performed after FDR setup of ≤0.05 and fold change of ≥2 or ≤−2. GSEA was performed on genes, ranked by log2FC in the comparison of CIML versus cNKs, using preranked GSEA (94, 95) on the MsigDB gene sets KEGG, Hallmark, and PID. Enrichment analysis for cytokine responses was performed using IREA (39) on top differentially expressed genes (FDR ≤ 0.05 and log2 fold change ≥2 or ≤−2.

Generation of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells

MSLN-CAR gene construct was designed with the following components: signal peptide (CD8), MSLN Scfv derived from the YP218 antibody (90), and transmembrane domain (CD8), followed by intracellular signaling domains, 4-1BB and CD3ζ. The CAR construct was linked to eGFP by P2A self-cleaving peptide that allowed for assessment of transduction efficiency. Lentiviral supernatants were produced using our BaLV system as reported previously (51) and titrated using Jurkat cells.

For the transduction, CIML NK cells rested for 24 hours were used. Forty-eight–well plates were coated with RetroNectin (20 μg/ml) for 2 hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The surface of the wells was blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin solution for 30 min and washed once with PBS after blocking. Vectofusion-1 (10 μg/ml) and CIML NK cells (250,000 per well) were added to the coated plates followed by the addition of virus at MOI = 0.5 or 1 (titrated using Jurkat cells). Spinfection was carried out for 90 mins at 4000 rpm at 37°C. After spinfection, NK MACS medium (from Miltenyi Biotech) supplemented with 5% human serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin was added to the transduced cells in the presence of IL-2 (500 U/ml). The cells were washed after three days and cultured in NK MACS medium in the presence of IL-2 (500 U/ml). The transduction of NK cells was evaluated by flow cytometry staining for human CD56+ CD3− cells and gating on GFP+ cells. Degranulation (CD107a) and IFN-γ production of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells were performed as reported in the previous section above.

Cytotoxicity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells against EOC cells

For long-term cytotoxicity, EOC cells (OVCAR8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3) were plated in a 96-well flat-bottom plate (4000 to 8000 cells per well) and allowed to adhere for 18 hours. Untransduced or CAR NK cells were added to the cancer cells at E:T ratios of 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8 and cocultured for 24 to 120 hours in the presence of low-dose IL-15 (1 ng/ml) and IL-2 (50 U/ml). Cell viability of cancer cells was evaluated via CCK8/WST-8 assay (Abcam) per the manufacturer’s directions. WST-8 solution (10 μl) was added per well and incubated for 3 to 5 hours. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 460 nm using a microplate reader. The specific cytotoxicity was calculated as 100-[(Abs cancer cells cocultured with NK/Abs cancer cells only) × 100]. NK cells alone and media were used as baseline.

Comparison of MSLN-CARs derived from SS1P and YP218

EOC cell lines (OVCAR8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3) were plated in a 96-well flat-bottom plate (4000 to 8000 cells per well) and allowed to adhere for 18 hours. CAR1-SS1P or CAR2-YP218 CIML NK cells were added to the cancer cells at E:T ratios of 1:2 and 1:4 and cocultured for 48 hours in the presence of low-dose IL-15 (1 ng/ml) and IL-2 (50 U/ml). Degranulation (CD107a) and IFN-γ production of CAR1-SS1P and CAR2-YP218 CIML NK cells were performed as reported in the previous section above.

Specificity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells

To evaluate the specificity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells against MSLN expressing tumor cells, SKOV3 (MSLN+), Panc1 (MSLN-), and K562 (MSLN-) were plated at a cell density of 4000 cells per well and allowed to adhere for 18 hours. Untransduced or CAR NK (specific CAR–MSLN and nonspecific CAR–CD19) cells were added to the cancer cells at E:T ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:4 and cocultured for 96 hours in the presence of low-dose IL-15 (1 ng/ml) and IL-2 (50 U/ml). The cell viability of cancer cells was evaluated using CCK8/WST-8 assay, and specific cytotoxicity was calculated as described in the previous section.

Comparison of CAR-cNK versus CAR-CIML NK cells

cNK and CIML NK cells were transduced following the same procedure detailed in the section above at different MOIs (0.5, 1, and 10). The transduction was evaluated on days 5 and 10 by flow cytometry staining for human CD56+ CD3- cells and gating on GFP+ cells. The CAR-cNK and CAR-CIML NK cells were counted on days 5 and 10 to evaluate cell proliferation. The cytotoxicity of CAR-cNK and CAR-CIML NK cells was measured against the following EOC cells: OVCAR8, SKOV3, and OVCAR3 at E:T ratios of 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 after 24 hours of coculture and cell killing measured by the CCK8 assay as described above.

Cytotoxicity of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells against PDX explants

The establishment, maintenance, and validation of the PDX models used in this study have been previously reported (56). The PDX cells from all the models (DF86, DF68, and DF59) exhibited 3D-spheroidal architecture. Hence, the spheroid count was used to set up the coculture experiments using 1000 spheroids (~50,000 cells total) per condition. Untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells were added at E:T ratio of 5:1 and 10:1. After 24 or 48 hours of coculture, the conditioned medium was collected to evaluate IFN-γ from the NK cells using ELISA. The cells were then dissociated via TrypLE dissociation solution (Gibco) for 8 to 10 mins, washed once with FACS buffer. The single cells were stained for EpCAM, Apotracker green (BioLegend), and Zombie NIR for 25 mins at room temperature. Cells were washed twice after the staining and evaluated using flow cytometry. NK cells from five independent healthy donors and PDX cells from three different models (each PDX model collected from at least two mice) were used for this study. Data were reported as the percentage of apoptotic cells (early plus late apoptotic cells) in EpCAM+ gated PDX cell population.

Incubation of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells in patient-derived ascites and after incubation analysis

Ascitic fluid was collected from patients with EOC undergoing paracentesis under Dana Farber Cancer Institute’s protocol (consented to the protocol 02-051). The ascitic fluid was centrifuged to collect the cells, passed through 40-μm filter, and collected and frozen at −80 for future experiments. The multiplexing analysis was performed using the Luminex 200 system (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) by Eve Technologies Corp. (Calgary, Alberta). Forty-eight markers were simultaneously measured in the samples using Eve Technologies’ Human Cytokine Panel A 48-Plex Discovery Assay (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The 48-plex consisted of sCD40L, EGF, Eotaxin, FGF2, FLT3 ligand, Fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GROα, IFN-α2, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1RA, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12(p40), IL-12(p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, IL-17E/IL-25, IL-17F, IL-18, IL-22, IL-27, IP10, MCP1, MCP3, M-CSF, MDC, MIG/CXCL9, MIP1α, MIP1β, PDGFAA, PDGFAB/BB, RANTES, TGF-α, TNF-α, TNF-β, and VEGF-A.

Untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells were incubated in media supplemented with IL-15 (1 ng/ml) or in ascitic fluid diluted by 50% (v/v). After 48 hours, the cells were then collected and cocultured with EOC cells (OVCAR8 and SKOV3) for 24 hours at E:T ratio of 2:1 and 1:1 for further evaluation. IFN-γ assessment was done by ELISA of the supernatant, and cancer cell viability was determined using CCK8 assay as described above. IFN-γ ELISA was performed using Abcam ELISA kit and data reported as fold change in the IFN-γ level from NK cells cultured in 50% ascitic fluid versus media alone (IFN-γ production without ascitic fluid is denoted as 1.0).

For the phenotypic changes potentially induced by ascitic fluid, the cells were stained using our extensive flow panel as described above. Data reported as fold change of specific receptor expression on NK cells after exposure to ascitic fluid compared to the cells not exposed to ascitic fluid (media alone) with the receptor expression without ascitic fluid denoted as 1.0.

For the bulk RNA sequencing, untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells were incubated in the ascitic fluid (50% dilution by volume as above) or media alone for 48 hours and then washed once with PBS, and dry pellets were stored in −80°C. RNA preparation and quantification were performed at MedGenome and analyzed using Partek Flow Genome analysis software as described in detail in the previous section. Gene expression was determined with fold change of ≥2 due to the donor and patient-sample variability.

In vivo therapeutic efficacy of MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells

All animal experiments in this study were approved by institutional guidelines (protocol 08-023). NOD NSG mice (6 to 8 week old) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. OVCAR8 cells were transduced with mCherry-luciferase- (mcLuc) using lentivirus and followed by puromycin selection. OVCAR8-mcLuc cells (1 million) were injected intraperitoneally in PBS: Matrigel mixture (1:1, 100 μl, Corning GFR phenol red-free). One week after the cancer cell implantation, mice were randomized into three groups (seven to nine mice per group): Control (no NK cells), untransduced CIML NK, and MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells. The mice in the treatment group received two doses of untransduced or MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells intraperitoneally (5 million cells per dose on days 8 and 15) after being transduced and cultured ex vivo after 15 to 20 days. The mice received 75,000 IU of human recombinant IL-2 (intraperitoneally) every other day to support adoptively transferred human NK cells. Mice were monitored for a total of 40 days after tumor implantation, and the tumor progression was measured via BLI imaging every week.

At the end point (40 days after tumor implantation and 32 days after adoptive transfer of NK cells), five mice from each group were euthanized and major organs including tumor site, liver, lungs, and spleen were collected. A small fragment of the tissue was fixed in buffered formalin for immunohistochemistry analysis. The remaining tissue was homogenized using Miltenyi Octadissociators following the manufacturer’s protocol. A small portion of the single-cell suspension was separated for the detection of tumor cells in each organ using flow cytometry. The remaining cell suspension was used to collect lymphocytes via Percoll density gradient. The lymphocytes were stained using a panel to detect human NK cells in different organs. The remaining mice (three mice per group) were monitored for survival, and mice were euthanized upon disease progress, over-distended abdomen (due to the growth of solid tumors and ascites), 15% loss in body weight, or poor body condition.

Phenotypic assessment of adoptively transferred MSLN-CAR CIML NK cells

A separate cohort of mice (n = 5 per group) was injected with a single dose of untransduced or CAR-CIML NK cells, 8 days after the OVCAR8-mcLuc tumor cell implantation (intraperitoneal). Mice were euthanized on day 14 (8 days after NK cell injection), and major organs including liver, lungs, and spleen as well as peritoneal washings and blood were collected. The tissues were homogenized using Miltenyi’s Octadissociator following the manufacturer’s protocol. Lymphocytes were collected from the single-cell suspensions via Percoll density gradient and stained using an antibody panel to detect human NK cells in different organs. The antibody panel included the following: murine-CD45, human CD45, CD56, and key activating/inhibitory receptors including CD16, NKp30, DNAM1, Tim3, TIGIT, and NKG2A to decipher the phenotype of adoptively transferred NK cells.

Statistical analysis

All the data are represented as means ± SD unless mentioned otherwise. For the apoptotic cell analysis, cytotoxicity analysis, and in vivo therapeutic experiments, the statistical significance between the groups was determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with donor-matched Sidak’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons. For the gene expression analysis, pipelines created and optimized by Partek Flow Genomic analysis software were used with the FDR setup of ≤0.05 and fold change of ≥2 unless mentioned otherwise. For the survival analysis, statistical comparisons were determined using log-rank test. All the statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla California, CA, USA) with α = 0.05 and reported as stars assigned to the P values; ****P ≤ 0.0001, ***P ≤ 0.001, **P ≤ 0.01, *P ≤ 0.05, and ns P > 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank the valuable feedback and suggestions from S. Hill (DFCI). We thank the Specialized Histopathology Core (BWH) for providing histology and immunohistochemistry services and the Experimental Core of the Belfer Center for Applied Cancer Science for the patient-derived xenograft explants. We thank the Lurie Family Imaging Center and the staff. All the representative graphics figures were created in BioRender.com.

Funding: This work was supported by Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Ovarian Cancer SPORE grant (1P50CA240243-01A1), the Ted and Eileen Pasquarello Research Fund, and the philanthropic support to Rizwan Romee. Additional funding was received in part from the Expert Miracles Foundation and the Robert A. and Renée E. Belfer Family Foundation.

Author contributions: M.T. and R.R. were involved in the initial conceptualization of the study, data analysis, supervision, and writing and editing the manuscript. M.T., K.D., and J.V. designed the experiments, analysis, and data interpretation, and contributed to the manuscript editing. G.B., M.S., and R.S. evaluated the gene analysis and data interpretation and edited the manuscript. Y.Z.A., I.E.K., O.A., A.M., O.B., E.B., A.K.A, H.D., and J.D.H. were involved in the optimization of the experiments and assisted during the experimental procedures and data analysis. S.J., A.B.C., and Q.-D.N. provided methodology and optimized the in vivo experiments. S.G. and C.C. maintained the PDX models and harvested the cells for the ex vivo experiments. P.C.G. and C.P.P were involved in the conceptualization, methodology, and supervision of the PDX experiments. J.K., D.A.B., U.A.M., R.J.S., R.L.P., J.R., and J.C. were involved in the refining of the study concept, provided resources and methodology for the study, and substantively revised the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests: R.R. has a sponsored research agreement with Crispr Therapeutics and Skyline Therapeutics and serves on the scientific advisory board of Glycostem Therapeutics. R.R and J.C are cofounders of the InnDura Therapeutics. J.R. received research funding from Kite/Gilead, Novartis, and Oncternal Therapeutics and serves on advisory boards for Akron Biotech, Clade Therapeutics, Garuda Therapeutics, LifeVault Bio, Novartis, and Smart Immune. D.A.B. is a consultant for N of One/Qiagen and Nerviano Medical Sciences; is a founder and shareholder in Xsphera Biosciences; and has received honoraria from Merck, H3 Biomedicine/Esai, EMD Serono, Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, and Madalon Consulting, and research grants from BMS, Takeda, Novartis, Gilead, and Lilly. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S18

Table S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Wagle N. S., Jemal A., Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter R., Matulonis U. A., Immunotherapy for ovarian cancer. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 20, 240–253 (2022). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akter S., Rahman M. A., Hasan M. N., Akhter H., Noor P., Islam R., Shin Y., Rahman M. D. H., Gazi M. S., Huda M. N., Nam N. M., Chung J., Han S., Kim B., Kang I., Ha J., Choe W., Choi T. G., Kim S. S., Recent advances in ovarian cancer: Therapeutic strategies, potential biomarkers, and technological improvements. Cells 11, 650 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert C., A decade of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. 11, 3801 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiravand Y., Khodadadi F., Kashani S. M. A., Hosseini-Fard S. R., Hosseini S., Sadeghirad H., Ladwa R., O’Byrne K., Kulasinghe A., Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. 29, 3044–3060 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang L., Conejo-Garcia J. R., Katsaros D., Gimotty P. A., Massobrio M., Regnani G., Makrigiannakis A., Gray H., Schlienger K., Liebman M. N., Rubin S. C., Coukos G., Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 203–213 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato E., Olson S. H., Ahn J., Bundy B., Nishikawa H., Qian F., Jungbluth A. A., Frosina D., Gnjatic S., Ambrosone C., Kepner J., Odunsi T., Ritter G., Lele S., Chen Y.-T., Ohtani H., Old L. J., Odunsi K., Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18538–18543 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore K. N., Bookman M., Sehouli J., Miller A., Anderson C., Scambia G., Myers T., Taskiran C., Robison K., Mäenpää J., Willmott L., Colombo N., Thomes-Pepin J., Liontos M., Gold M. A., Garcia Y., Sharma S. K., Darus C. J., Aghajanian C., Okamoto A., Wu X., Safin R., Wu F., Molinero L., Maiya V., Khor V. K., Lin Y. G., Pignata S., Atezolizumab, bevacizumab, and chemotherapy for newly diagnosed stage III or IV ovarian cancer: Placebo-controlled randomized phase III trial (IMagyn050/GOG 3015/ENGOT-OV39). J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 1842–1855 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disis M. L., Taylor M. H., Kelly K., Beck J. T., Gordon M., Moore K. M., Patel M. R., Chaves J., Park H., Mita A. C., Hamilton E. P., Annunziata C. M., Grote H. J., von Heydebreck A., Grewal J., Chand V., Gulley J. L., Efficacy and safety of avelumab for patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: Phase 1b results from the JAVELIN solid tumor trial. JAMA Oncol. 5, 393–401 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matulonis U. A., Shapira-Frommer R., Santin A. D., Lisyanskaya A. S., Pignata S., Vergote I., Raspagliesi F., Sonke G. S., Birrer M., Provencher D. M., Sehouli J., Colombo N., González-Martín A., Oaknin A., Ottevanger P. B., Rudaitis V., Katchar K., Wu H., Keefe S., Ruman J., Ledermann J. A., Antitumor activity and safety of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer: Results from the phase II KEYNOTE-100 study. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1080–1087 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamanishi J., Takeshima N., Katsumata N., Ushijima K., Kimura T., Takeuchi S., Matsumoto K., Ito K., Mandai M., Nakai H., Sakuragi N., Watari H., Takahashi N., Kato H., Hasegawa K., Yonemori K., Mizuno M., Takehara K., Niikura H., Sawasaki T., Nakao S., Saito T., Enomoto T., Nagase S., Suzuki N., Matsumoto T., Kondo E., Sonoda K., Aihara S., Aoki Y., Okamoto A., Takano H., Kobayashi H., Kato H., Terai Y., Takazawa A., Takahashi Y., Namba Y., Aoki D., Fujiwara K., Sugiyama T., Konishi I., Nivolumab versus gemcitabine or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: Open-label, randomized trial in Japan (NINJA). J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 3671–3681 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brudno J. N., Kochenderfer J. N., Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: Recognition and management. Blood 127, 3321–3330 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mansouri V., Yazdanpanah N., Rezaei N., The immunologic aspects of cytokine release syndrome and graft versus host disease following CAR T cell therapy. Int. Rev. Immunol. 41, 649–668 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarannum M., Romee R., Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 592 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarannum M., Romee R., Shapiro R. M., Innovative strategies to improve the clinical application of NK cell-based immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 13, 859177 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang C., Qin C., Lin Y., Development and validation of a prognostic risk model based on nature killer cells for serous ovarian cancer. J. Pers. Med. 13, 403 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Y., Yao Z., Zhao Z., Xiao H., Xia M., Zhu X., Jiang X., Sun C., Natural killer cells inhibit metastasis of ovarian carcinoma cells and show therapeutic effects in a murine model of ovarian cancer. Exp. Ther. Med. 16, 1071–1078 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romee R., Rosario M., Berrien-Elliott M. M., Wagner J. A., Jewell B. A., Schappe T., Leong J. W., Abdel-Latif S., Schneider S. E., Willey S., Neal C. C., Yu L., Oh S. T., Lee Y.-S., Mulder A., Claas F., Cooper M. A., Fehniger T. A., Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 357ra123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romee R., Schneider S. E., Leong J. W., Chase J. M., Keppel C. R., Sullivan R. P., Cooper M. A., Fehniger T. A., Cytokine activation induces human memory-like NK cells. Blood 120, 4751–4760 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper M. A., Elliott J. M., Keyel P. A., Yang L., Carrero J. A., Yokoyama W. M., Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1915–1919 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni J., Miller M., Stojanovic A., Garbi N., Cerwenka A., Sustained effector function of IL-12/15/18-preactivated NK cells against established tumors. J. Exp. Med. 209, 2351–2365 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berrien-Elliott M. M., Cashen A. F., Cubitt C. C., Neal C. C., Wong P., Wagner J. A., Foster M., Schappe T., Desai S., McClain E., Becker-Hapak M., Foltz J. A., Cooper M. L., Jaeger N., Srivatsan S. N., Gao F., Romee R., Abboud C. N., Uy G. L., Westervelt P., Jacoby M. A., Pusic I., Stockerl-Goldstein K. E., Schroeder M. A., DiPersio J., Fehniger T. A., Multidimensional analyses of donor memory-like NK cells reveal new associations with response after adoptive immunotherapy for leukemia. Cancer Discov. 10, 1854–1871 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro R. M., Birch G. C., Hu G., Vergara Cadavid J., Nikiforow S., Baginska J., Ali A. K., Tarannum M., Sheffer M., Abdulhamid Y. Z., Rambaldi B., Arihara Y., Reynolds C., Halpern M. S., Rodig S. J., Cullen N., Wolff J. O., Pfaff K. L., Lane A. A., Lindsley R. C., Cutler C. S., Antin J. H., Ho V. T., Koreth J., Gooptu M., Kim H. T., Malmberg K.-J., Wu C. J., Chen J., Soiffer R. J., Ritz J., Romee R., Expansion, persistence, and efficacy of donor memory-like NK cells infused for posttransplant relapse. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e154334 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassan R., Bera T., Pastan I., Mesothelin: A new target for immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3937–3942 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassan R., Kreitman R. J., Pastan I., Willingham M. C., Localization of mesothelin in epithelial ovarian cancer. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 13, 243–247 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coelho R., Ricardo S., Amaral A. L., Huang Y.-L., Nunes M., Neves J. P., Mendes N., López M. N., Bartosch C., Ferreira V., Portugal R., Lopes J. M., Almeida R., Heinzelmann-Schwarz V., Jacob F., David L., Regulation of invasion and peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer by mesothelin manipulation. Oncogenesis 9, 61 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z., Li N., Feng K., Chen M., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Yang Q., Nie J., Tang N., Zhang X., Cheng C., Shen L., He J., Ye X., Cao W., Wang H., Han W., Phase I study of CAR-T cells with PD-1 and TCR disruption in mesothelin-positive solid tumors. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 18, 2188–2198 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beatty G. L., O’Hara M. H., Lacey S. F., Torigian D. A., Nazimuddin F., Chen F., Kulikovskaya I. M., Soulen M. C., McGarvey M., Nelson A. M., Gladney W. L., Levine B. L., Melenhorst J. J., Plesa G., June C. H., Activity of mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells against pancreatic carcinoma metastases in a phase 1 trial. Gastroenterology 155, 29–32 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haas A. R., Tanyi J. L., O’Hara M. H., Gladney W. L., Lacey S. F., Torigian D. A., Soulen M. C., Tian L., McGarvey M., Nelson A. M., Farabaugh C. S., Moon E., Levine B. L., Melenhorst J. J., Plesa G., June C. H., Albelda S. M., Beatty G. L., Phase I study of lentiviral-transduced chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells recognizing mesothelin in advanced solid cancers. Mol. Ther. 27, 1919–1929 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beatty G. L., Haas A. R., Maus M. V., Torigian D. A., Soulen M. C., Plesa G., Chew A., Zhao Y., Levine B. L., Albelda S. M., Kalos M., June C. H., Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce antitumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 112–120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan R., Butler M., O’Cearbhaill R. E., Oh D. Y., Johnson M., Zikaras K., Smalley M., Ross M., Tanyi J. L., Ghafoor A., Shah N. N., Saboury B., Cao L., Quintás-Cardama A., Hong D., Mesothelin-targeting T cell receptor fusion construct cell therapy in refractory solid tumors: Phase 1/2 trial interim results. Nat. Med. 29, 2099–2109 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M.-J., Yan S.-B., Chen G., Li G.-S., Yang Y., Wei T., He D.-S., Yang Z., Cen G.-Y., Wang J., Liu L.-Y., Liang Z.-J., Chen L., Yin B.-T., Xu R.-X., Huang Z.-G., Upregulation of CCNB2 and Its perspective mechanisms in cerebral ischemic stroke and all subtypes of lung cancer: A comprehensive study. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 16, 854540 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owa M., Dynlacht B., A non-canonical function for centromere-associated protein-E controls centrosome integrity and orientation of cell division. Commun. Biol. 4, 358 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li N., Chu J., Hu K., Zhang H., Li N., Chu J. F., Hu K. Y., Zhang H. Y., ASPM overexpression enhances cellular proliferation and migration and predicts worse prognosis for papillary renal cell carcinoma. J. Biosci. 48, 17 (2023). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdallah F., Coindre S., Gardet M., Meurisse F., Naji A., Suganuma N., Abi-Rached L., Lambotte O., Favier B., Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptors in regulating the immune response in infectious diseases: A window of opportunity to pathogen persistence and a sound target in therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 12, 717998 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu S., Sun Z., Li L., Liu J., He J., Song D., Shan G., Liu H., Wu X., Induction of T cells suppression by dendritic cells transfected with VSIG4 recombinant adenovirus. Immunol. Lett. 128, 46–50 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ducamp S., Luscieti S., Ferrer-Cortès X., Nicolas G., Manceau H., Peoc’h K., Yien Y. Y., Kannengiesser C., Gouya L., Puy H., Sanchez M., A mutation in the iron-responsive element of ALAS2 is a modifier of disease severity in a patient suffering from CLPX associated erythropoietic protoporphyria. Haematologica 106, 2030–2033 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner A., Sasse J., Varadi A., Rapid detection of pathological mutations and deletions of the haemoglobin beta gene (HBB) by high resolution melting (HRM) analysis and gene ratio analysis copy enumeration PCR (GRACE-PCR). BMC Med. Genet. 17, 75 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cui A., Huang T., Li S., Ma A., Pérez J. L., Sander C., Keskin D. B., Wu C. J., Fraenkel E., Hacohen N., Dictionary of immune responses to cytokines at single-cell resolution. Nature 625, 377–384 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spranger S., Gajewski T. F., Mechanisms of tumor cell–intrinsic immune evasion. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2, 213–228 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nachef M., Ali A. K., Almutairi S. M., Lee S.-H., Targeting SLC1A5 and SLC3A2/SLC7A5 as a potential strategy to strengthen anti-tumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 12, 624324 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He J., Liu D., Liu M., Tang R., Zhang D., Characterizing the role of SLC3A2 in the molecular landscape and immune microenvironment across human tumors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 961410 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreß J. K. C., Jessen C., Hufnagel A., Schmitz W., Xavier da Silva T. N., Ferreira Dos Santos A., Mosteo L., Goding C. R., Friedmann Angeli J. P., Meierjohann S., The integrated stress response effector ATF4 is an obligatory metabolic activator of NRF2. Cell Rep. 42, 112724 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu K., Chen Y., Li B., Li Y., Liang X., Lin H., Luo L., Chen T., Dai Y., Pang W., Zeng L., Upregulation of apolipoprotein L6 improves tumor immunotherapy by inducing immunogenic cell death. Biomolecules 13, 415 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]