Abstract

Cancer exhibits heterogeneity that enables adaptability and remains grand challenges for effective treatment. Chemotherapy is a validated and critically important strategy for the treatment of cancer, but the emergence of multidrug resistance which may lead to recurrence of disease or even death is a major hurdle for successful chemotherapy. Azoles and sulfonamides are important anticancer pharmacophores, and azole–sulfonamide hybrids have the potential to simultaneously act on dual/multiple targets in cancer cells, holding great promise to overcome drug resistance. This review outlines the current scenario of azole–sulfonamide hybrids with the anticancer potential, and the structure–activity relationships as well as mechanisms of action are also discussed, covering articles published from 2020 onward.

Keywords: : azole, cancer, drug resistance, hybrid molecules, sulfonamide

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

The goal of this review is to highlight the current scenario of azole–sulfonamide hybrids with anticancer potential, covering articles published from 2020 onward. The critical aspects of design, structure–activity relationships and mechanisms of action are also discussed to continuously pave the way for the exploration of more effective candidates.

Plain language summary

Article highlights.

Azole and sulfonamide moieties are important anticancer pharmacophores.

Combination of azole with sulfonamide into one molecule with various linkers is a promising strategy to provide novel anticancer candidates.

Several azole–pyrimidine hybrids exhibited profound anticancer potential against a broad range of cancers derived from various tissues, favorable pharmacokinetic properties, low acute toxicity and less probability to generate drug resistance.

The structure–activity relationships were enriched which may facilitate further rational design of more effective candidates.

1. Background

Cancer as one of the deadliest diseases is responsible for around 19.3 million new cases and approximately 10.0 million deaths in 2020 according to the World Health Organization estimation [1,2]. The morbidity and mortality of cancer are projected to rise to over 29.5 million and 16.3 million by 2040, posing a great threat to the lives all over the world [3,4]. Substantial achievements have been made in the diagnosis and management of cancer in recent decades, and the number of cancer survivors continues to increase [5,6]. The modern era of cancer chemotherapy began in the 1940s, and currently, hundreds of chemotherapeutics have been approved for cancer therapy [7,8]. Thus, chemotherapeutic agents play a vital role in cancer therapy. However, the actual clinical efficacy of chemotherapy is restricted by drug resistance and severe side effects, highlighting the urgent need to explore novel anticancer chemotherapeutics [9,10].

Azoles serve as privileged templates in the contemporary drug design paradigm due to their capability to form various noncovalent interactions with different therapeutic targets and possess unique physicochemical profiles that promote the development of highly selective and physiological benevolent chemotherapeutics [11,12]. Sulfonamide, a bioisostere of carboxylic group, has emerged as one of the relatively well-explored scaffolds for the development of anticancer chemotherapeutics since its derivatives have the potential to cause cancer cell cycle arrest, induce apoptosis, inhibit angiogenesis and disrupt cell migration [13,14]. Hybrid molecules with intrinsic versatility and unique physicochemical properties exhibit promising activity against various cancers including drug-resistant forms through multi-target therapy and can reduce side effects caused by the corresponding pharmacophores [15,16]. Accordingly, hybridization of azoles with sulfonamide appears to be a judicious strategy to develop novel effective anticancer candidates.

The current scenario of azole–sulfonamide hybrids with anticancer potential, and structure–activity relationships (SARs) as well as mechanisms of action were highlighted in this manuscript, covering articles published from 2020 onward to continuously pave the way for the exploration of more effective candidates.

2. Sulfonamide–benzimidazole/imidazole hybrids

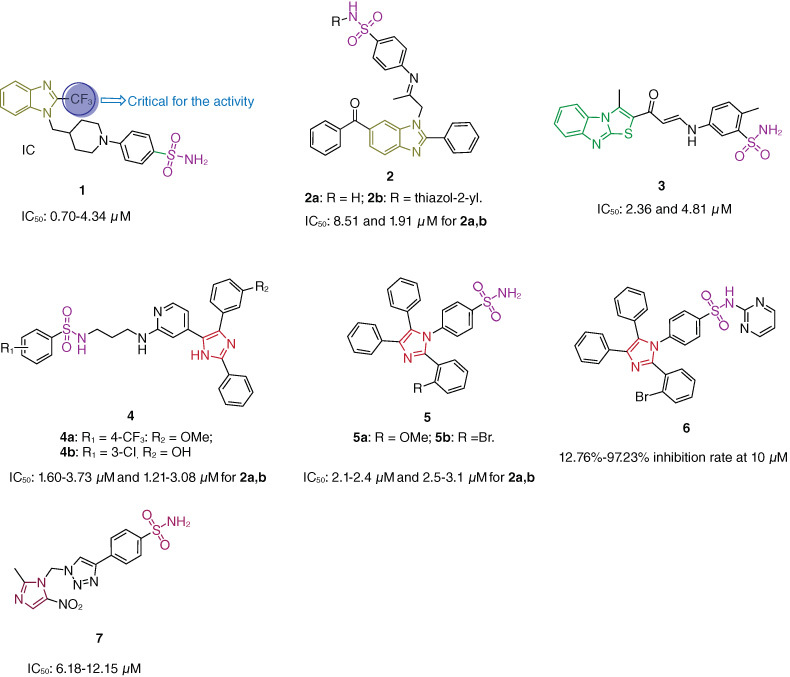

FA16 (Figure 1, 1; half maximal inhibitory concentration/IC50: 0.70–4.34 μM, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide/MTT assay), a sulfonamide–benzimidazole hybrid, possessed potent antiproliferative activity against HeLa, HT1080, MDA-MB-231, 786-O, HepG2, A375 and DU145 cancer cell lines and displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 20 μM) toward normal AC16, NCM460 and LO2 cell lines [17]. The SAR indicated that trifluoromethyl group at C-2 position of benzimidazole moiety was critical for the activity, and sulfonamide moiety was favorable to the activity. Mechanistically, FA16 could activate ferroptotic cell death by inhibiting cystine/glutamate antiporter (system Xc-). Moreover, FA16 (half-life/t1/2: 10.4 and 15.6 min) also demonstrated more metabolic stability than erastin (t1/2: 3.5 and 4.0 min) in rat and human microsomes. In the HepG2 xenografted mouse model, FA16 (30 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) significantly inhibited tumor growth with tumor growth inhibition (TGI) value of 77.1%, and no significant loss of body weight or major abnormality in the heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney was observed in FA16-treated mice group. Taken together, FA16 could serve as a promising anti-liver cancer candidate for further preclinical evaluations.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of sulfonamide–benzimidazole/imidazole hybrids 1–7.

Sulfonamide–benzimidazole hybrids 2a,b (IC50: 8.51 and 1.91 μM, MTT assay) showed promising antiproliferative activity against HeLa cancer cells, revealing that incorporation of thiazole fragment into sulfonamide skeleton was beneficial for the activity [18]. Hybrid 2b (IC50: 13.62 μM) also displayed relatively low cytotoxicity toward normal WI-38 cells, and the selectivity index (SI: IC50(normal cells)/IC50(cancer cells)) value was 7.1, revealing its good selectivity profile. Moreover, hybrid 2b (IC50: 342 and 290 nM) possessed dual inhibition activity against both epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2) kinases. Molecular docking analysis suggested that hybrid 2b tightly interacted with the amino acid residues in the active binding site of HER2 kinase and formed strong hydrogen bond with Gly881 in the activation loop.

Sulfonamide–thiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazole hybrid 3 (IC50: 2.36 and 4.81 μM, MTT assay) was superior to staurosporine (IC50: 7.33 and 6.75 μM) against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines [19]. Mechanistically, hybrid 3 could arrest cell cycle at G2/M phase and induce early as well as late apoptosis through increased the caspase-3 level. In silico studies showed that thiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazole moiety could effectively establish a plenty of hydrophobic interactions in addition to involvement of nitrogen of the tricycle moiety in hydrogen-bonding within hCA IX and XII active sites.

Sulfonamide–imidazole hybrids 4a,b (IC50: 1.60–3.73 μM and 1.21–3.08 μM, Sulforhodamine B/SRB assay) not only possessed potent broad-spectrum antiproliferative activity against a panel of 60 cancer cell lines derived from CNS, melanoma, leukemia, lung, colon, ovarian, renal, prostate and breast, but also demonstrated great inhibitory effects (IC50: 630 and 120 nM) against BRAFV600E kinase [20]. Mechanistically, hybrid 4b caused cell cycle arrest at G1 and S phases and induced both apoptosis and necrosis. Sulfonamide–imidazole hybrids 5a,b (IC50: 2.1–2.4 μM and 2.5–3.1 μM, MTT assay) were not inferior to doxorubicin (IC50: 0.9–1.4 μM) against A549, MCF-7, Panc-1 and HT-29 cancer cell lines [21]. The SAR revealed that introduction of pyrimidine into sulfonamide moiety was tolerated and growth inhibition rates of hybrid 6 were in a range of 12.76–97.23% at 10 μM against the 60 cancer cell lines [22]; incorporation of nitro group into imidazole moiety was also permitted, and hybrid 7 (IC50: 6.18–12.15 μM, MTT assay) showed considerable antiproliferative activity against HCT-116, HeLa and MCF-7 cancer cell lines, and the activity was comparable to that of doxorubicin (IC50: 5.23 μM) against HCT-116 cancer cells [23]; imidazole moiety was critical for the activity, and replacement by imidazolone or imidazoline led to loss of activity [24,25]. The molecular docking study revealed that hybrid 7 could interact with CA IX isoform by binding to the zinc ion (Zn2+) as well as the essential active site amino acids, His96 and His94. In addition, hybrid 7 also showed the crucial interactions adopted by acetazolamide (the co-crystallized ligand) with additional interactions with serine amino acids.

3. Sulfonamide–triazole hybrids

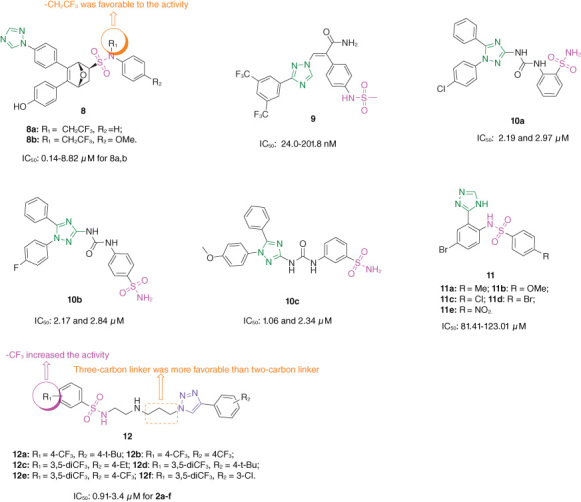

The majority of sulfonamide–oxabicycloheptene-1,2,4-triazole hybrids 8 (Figure 2; IC50: 0.14–24.82 μM, CCK-8 assay) were active against MCF-7 and tamoxifen-resistant LCC2 breast cancer cell lines, and the antiproliferative SARs illustrated that 1,2,4-triazole moiety was favorable to the antiproliferative activity, and replacement by pyrazole or phenyl ring decreased the activity; trifluoroethyl group at N-position of sulfonamide fragment was beneficial for the antiproliferative activity [26]. Among them, hybrids 8a,b (IC50: 0.14–8.82 μM) were not inferior to fulvestrant (IC50: 0.16 and 11.52 μM) and oxabicycloheptene sulfonamide (IC50: 0.97 and 4.37 μM) against the two tested breast cancer cell lines and displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 26.33 and 50.88 μM) toward normal MCF-10A breast cells. The docking study showed that hybrids 8a,b shared some hydrogen bonds in common, with phenolic hydroxyls bonding with Q225, and oxygen atoms of bicyclic ring bonding with T310. Moreover, hybrids 8a,b could target on both estrogen receptor α (Erα) and aromatase. The pharmacokinetic studies revealed that hybrid 8a (2.5 mg/kg, intravenous injection) showed half-life (t1/2) of 0.9 h, peak time (tmax) of 0.08 h, plasma clearance (CL) of 331.9 l/h/kg, and the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC0-∞) of 9400 ng•h/ml. In the MCF-7 xenografted mice model, hybrid 8a (TGI: 55% and ∼70% respectively at doses of 5.0 and 10 mg/kg through intraperitoneal injection) was comparable to fulvestrant (TGI: ∼50% at a dose of 5 mg/kg). Notably, no loss of body weight or significant changes in animal mortality or evident toxicity in main organs such as heart, liver and kidney were observed in hybrid 8a-treated mice group, demonstrating its good safety profile. Accordingly, hybrid 8a could serve as a promising candidate for the treatment of both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant breast cancers.

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of sulfonamide–triazole hybrids 8–12.

Sulfonamide–1,2,4-triazole hybrid 9 (IC50: 24.0–201.8 nM, CCK-8 assay) was highly potent against MM.1.S, Mino, VAL, Rael, Namaiwa, Mutu, H9, JB6 and YT myeloma cell lines, and the activity was superior to that of KPT-8602 (IC50: 64.0–333.5 nM) [27]. In addition, hybrid 9 indeed bound on the nuclear export signal (NES) binding pocket of Exportin 1 (XPO1) and could block the external transportation of cargos from nucleus to cytoplasm, which revealed that the induction of cell arrest and apoptosis, as well as inhibitory activity, was on-target effect of hybrid 9. Hybrid 9 showed good metabolic stability with t1/2 values of >60 min in rat plasma and liver microsomes. Moreover, hybrid 9 (10 mg/kg, oral gavage) also possessed acceptable pharmacokinetic properties with t1/2 of 2.21 h, Cmax of 1391 ng/ml, CL of 1638 ml/h/kg, AUC0-∞ of 6387 ng•h/ml and oral bioavailability of 34.6%. Thus, hybrid 9 could be served as a useful scaffold for the development of novel anti-multiple myeloma agents.

Sulfonamide–urea–1,2,4-triazole hybrids 10a–c (IC50: 1.06–2.97 μM, MTT assay) were more potent than staurosporine (IC50: 3.18 and 7.12 μM) against MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cell lines and exhibited profound inhibitory effects (IC50: 183–318 nM) against vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) [28]. In addition, hybrids 10a–c (IC50: 31.7, 47.5 and 64.9 μM) displayed relatively low cytotoxicity toward normal MCF-10A breast cells, and the SI values were ranging from 10.6 to 29.9, revealing their good selectivity profiles. The SAR indicated that urea linker between 1,2,4-triazole and phenyl ring was favorable to the activity, and removal of urea linker led to significant loss of activity as evidenced by that hybrids 11 (IC50: 81.41–123.01 μM, MTT assay) only exhibited weak to moderate antiproliferative activity against A375 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines [29]. The docking of 10b into hCA XII revealed that Zn2+ coordinated by the deprotonated NH-, the sulfonamide benzene ring could interact with His91 via π–π stacking interaction and the fluorinated phenyl ring was involved in a N–π interaction with Lys69 besides hydrophobic interactions with Lys69 and Asn64.

The antiproliferative SARs of sulfonamide–1,2,3-triazole hybrids 12 (IC50: 0.91–30 μM, MTT assay) against MCF-7, A2780, HT29, U87, H460, A431, Du145, BE2-C, SJ-G2 and MiapaCa-2 cancer cell lines elucidated that the length of carbon spacer between 1,2,3-triazole and amino group had great influence on the activity, and hybrids with three-carbon linker showed higher antiproliferative activity than their two-carbon linker analogs; trifluoromethyl group on the phenyl ring attached sulfonamide moiety was more favorable than nitro group, and incorporation of the second trifluoromethyl group further increased the activity [30]. The molecular docking study indicated that these hybrids engaged with the p53 groove through arene–hydrogen interactions between the triazole rings and PheA89, and between the substituted phenyl ring and PheA89, respectively. Among them, hybrids 12a–f (IC50: 0.91–3.4 μM) exhibited excellent antiproliferative activity against the tested cancer cell lines and warranted further investigations.

4. Sulfonamide–oxazole/oxadiazole hybrids

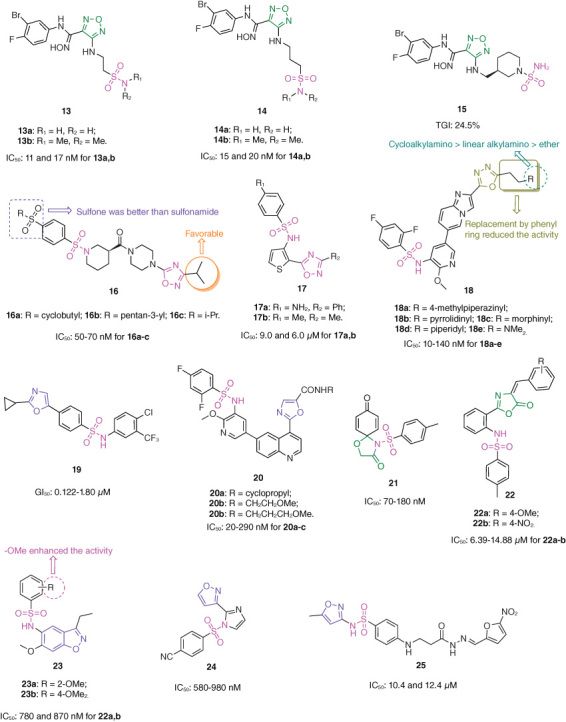

The antiproliferative SARs of sulfonamide–1,2,5-oxadiazole hybrids 13 (Figure 3; IC50: 11->800 nM, MTT assay) against HeLa cancer cells revealed that large volume substituents at R1 and R2 positions decreased the activity, while extension of the carbon spacer between sulfonamide and 1,2,5-oxadiazole was permitted [31]. Among them, hybrids 13a,b (IC50: 11 and 17 nM) and 14a,b (IC50: 15 and 20 nM) were not inferior to epacadostat (IC50: 8.0 nM) against HeLa cancer cells and showed profound inhibitory effects (IC50: 71–126 nM) against indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1). In the LLC xenografted mice model, hybrid 13a (TGI: ∼35% at a dose of 100 mg/kg via oral administration) was comparable to epacadostat (TGI: ∼40%) in terms of inhibition of tumor growth at the same condition, and no significant body weight loss was observed. Further studies indicated that incorporation of piperidine between sulfonamide and 1,2,5-oxadiazole moieties was tolerated. In the CT26 xenografted mice model, hybrid 15 (TGI: 24.5% at a dose of 100 mg/kg via oral administration) was slightly more potent than epacadostat (TGI: 23.4%), and no significant change of body weight was observed [32]. Moreover, hybrid 15 (20 mg/kg, oral administration) possessed improved pharmacokinetic properties with longer half-life (t1/2: 3.81 vs. 2.59 h) and better oral bioavailability (F%: 33.6 vs. 22.1%) compared with epacadostat. Taken together, hybrids 13a and 15 could serve as promising candidates and merited further preclinical evaluations.

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of sulfonamide–oxazole/oxadiazole hybrids 13–25.

Sulfonamide–1,2,4-oxadiazole hybrids 16 (IC50: 0.04–3.3 μM, MTT assay) exhibited excellent antiproliferative activity against MIA PaCa-2 cancer cells, and the SARs illustrated that sulfone was better than sulfonamide on the phenyl ring; iso-propyl group at C-3 position of 1,2,4-oxadiazole moiety enhanced the activity [33]. Among them, the representative hybrids 16a–c (IC50: 50–70 nM) showed pronounced antiproliferative activity against MIA PaCa-2 cancer cells. In particular, DX3–234 (16a, 5.0 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) suppressed ∼70% tumor growth without significant loss of body weight in the Pan02 xenografted mice model. Collectively, DX3–234 was a potential candidate for pancreatic cancer therapy.

OX18 and OX27 (17a,b, IC50: 9.0 and 6.0 μM, MTT assay), the sulfonamide–thiophene-1,2,4-oxadiazole hybrids, were not inferior to doxorubicin (IC50: 5.1 μM) against HCT-116 cancer cells, and the SAR demonstrated that electron-donating group at R1 position was favorable to the activity [34]. Mechanistically, OX27 decreased the expression of carbonic anhydrase (CA) IX, activated caspase-3, induced apoptosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, inhibited colony formation as well as migration of colon cancer cells. The molecular docking studies revealed that the sulfonamide group of OX27 formed a hydrogen bond with His64, nitrogen atom of oxadiazole formed a hydrogen bond with Gln92, -NH formed 2 additional hydrogen bonds with Thr200m, and phenyl linker formed π–π interactions with His94, π–sigma with Val121, π–sulfur with His96, π–alkyl with Val131 and Leu198.

The antiproliferative SARs of sulfonamide–imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-1,3,4-oxadiazole hybrids 18 (IC50: 10–260 nM, MTT assay) against HCT-116 cancer cells elucidated that (1) introduction of phenyl ring into C-5 position of 1,3,4-oxadiazole decreased the activity remarkably; (2) substituent at R position had great influence on the activity, and the relative contribution order was cycloalkylamino > linear alkylamino > ether [35]. Among them, hybrids 18a–e (IC50: 10–140 nM) were superior to HS-173 (IC50: 250 nM) against HCT-116 cancer cells. In particular, the most active hybrid 18a (IC50: 5.2–52 nM) was also highly active against MCF-7, HT-29, PC-3 and LOVO cancer cell lines and displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 15.53 μM) toward human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). In addition, hybrid 18a demonstrated great inhibitory effects against phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks, IC50: 0.2–1.2 nM against PI3Kα, PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ) and regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR, IC50: 21 nM). The analysis of hybrid 18a docked into the mTOR model indicated that there were hydrogen bonds between the nitrogen atom on the core and Val2240, and nitrogen atom on the piperazine ring and Thr2245. Hybrid 18a also possessed acceptable pharmacokinetic properties with t1/2 of 7.94 h, Cmax of 553 ng/ml, AUC0-∞ of 3965 h•ng/ml and oral bioavailability of 26.8%. In the HCT-116 xenografted mice model, hybrid 18a (TGI: 65.77% at a dose of 15 mg/kg by oral administration) was more potent than copanlisib (TGI: 57.89% at a dose of 15 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection) in terms of suppression of tumor growth. In the HT-29 xenografted mice model, hybrid 18a (TGI: 68.26% at a dose of 20 mg/kg by oral administration) was also not inferior to copanlisib (TGI: 60.67% at a dose of 15 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection) in inhibiting tumor growth. No obvious decrease of body weight was observed in hybrid 18a-treated group, but hybrid 18a induced obvious liver injury.

Sulfonamide–oxazole hybrid 19 (GI50: 0.122–1.80 μM, SRB assay) possessed potent broad-spectrum antiproliferative activity against a panel of 60 cancer cell lines derived from CNS, melanoma, ovarian, leukemia, lung, colon, renal, prostate and breast [36], whereas hybrids 20 (IC50: 20–460 nM, CCK-8 assay) exhibited excellent antiproliferative activity against MCF-7 and HCT-116 cancer cell lines [37]. The SARs for hybrids 20 illustrated that the amide fragment at C-5 position of oxazole moiety was essential for the activity, and replacement by ester resulted in significant loss of activity; alkyl side chain at R position was favorable to the activity, while phenyl ring decreased the activity [37]. Among them, hybrids 20a–c (IC50: 20–290 nM) were not inferior to omipalisib (IC50: >4 and 0.02 μM) and HS-173 (IC50: 1.76 and 0.19 μM) against MCF-7 and HCT-116 cancer cell lines. Moreover, hybrid 20a (IC50: 0.22 and 23 nM) as a promising dual inhibitor of PI3Kα and mTOR could effectively cause cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase and induce apoptosis. The molecular docking studies of hybrid 20a demonstrated that the oxygen atoms of methoxy and sulfonyl could form conservative hydrogen bonds with Lys802 in the affinity binding pocket, the nitrogen atom on the pyridine ring formed hydrogen bonds with Asp810, Tyr836 and Asp933 through a water molecule. In the hinge binding pocket, the nitrogen atom on the quinoline skeleton was able to form a conservative hydrogen bond with Val851, and the phenyl ring in the quinoline skeleton also formed a π–π interaction with Tyr836.

Sulfonamide–oxazolidin-4-one hybrid 21 (IC50: 70–180 nM, SRB assay) was 25.1–83.0-times superior to vorinostat (IC50: 3.52–9.13 μM) against MDA-MB-231, A549 and HeLa cancer cell lines [38]. Mechanistically, hybrid 21 could cause cell cycle arrest at the S phase and induce apoptosis. Moreover, hybrid 21 caused no obvious lesions in the major organs of mice even at a dose of 100 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection, revealing its excellent safety profile. In the 4T1 xenografted mice model, hybrid 21 (TGI: 39% at 10 mg/kg through intraperitoneal injection) showed potential in vivo efficacy without loss of body weight or side effects including apparent lesions in organs.

Sulfonamide–oxazolone hybrids 22 (IC50: 6.39–33.11 μM, SRB assay) showed considerable antiproliferative activity against HepG2, Panc-1 and BxPC-3 cancer cell lines, and the SAR revealed that replacement of phenyl ring by heteroaromatic ring could not enhance the activity [39]. Among them, the representative hybrids 22a,b (IC50: 6.39–14.88 μM) were not inferior to doxorubicin (IC50: 5.11–7.31 μM) against HepG2, Panc-1 and BxPC-3 cancer cell lines and were non-toxic (IC50: >50 μM) toward normal HPDE cells. Mechanistically, hybrids 22a,b triggered apoptosis by increasing the amounts of activated caspases 3/7 in Panc-1 cancer cells.

The antiproliferative SARs of sulfonamide–benzo[d]isoxazole hybrids 23 (IC50: 0.78–5.53 μM, CellTiter-Glo assay) against MV4–11 acute myeloid leukemia cells illustrated that methoxy group on the phenyl ring was essential for the high activity, and the representative hybrids 23a,b (IC50: 780 and 870 nM) were comparable to Y06036 (IC50: 850 nM) [40]. Further studies indicated that hybrids 23a,b inhibited the expression levels of oncogenes including c-Myc and CDK6, blocked cell cycle in MV4–11 cells at G0/G1 phase and induced cell apoptosis. The molecular docking studies indicated that the electron density maps of hybrids 23a,b showed excellent shape complementary with the protein binding pocket, and substituents at the 4′ or 5′ positions of the phenyl ring would push the benzene ring to the side away from Trp81.

Sulfonamide–isoxazole hybrid 24 (IC50: 580–980 nM, MTT assay) demonstrated profound antiproliferative activity against MCF-7, A549, Colo-205 and A2780 cancer cell lines and the activity was superior to that of etoposide (IC50: 1.31–3.08 μM) against MCF-7, A549 and A2780 cancer cell lines [41]. Furan-containing sulfonamide–isoxazole hybrid 25 (IC50: 10.4 and 12.4 μM, MTT assay) showed moderate antiproliferative activity against PPC-1 and CaKi-1 cancer cell lines, but this hybrid (IC50: 9.5 μM) displayed high cytotoxicity toward normal HF cells [42].

5. Sulfonamide–pyrazole/indazole hybrids

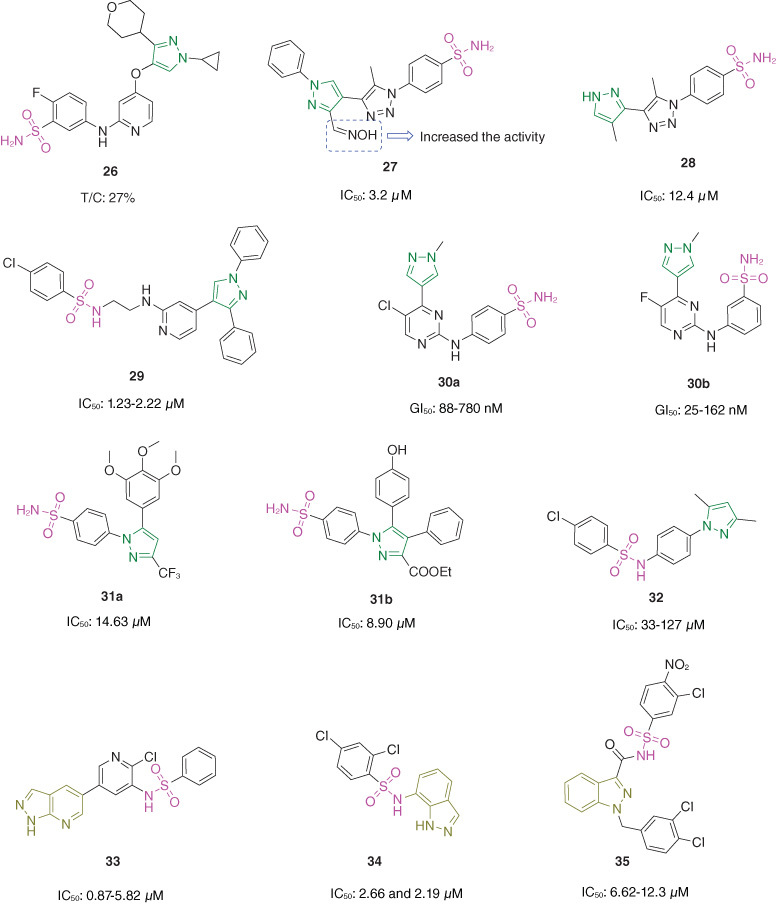

Sulfonamide–pyrazole hybrid 26 (Figure 4; IC50: 28 nM) showed great inhibitory activity against activin-like kinase 5 (ALK5) and possessed favorable pharmacokinetic properties in mice with t1/2 of 1.2 h, Cmax of 5134 ng•h, AUC0-∞ of 7703 ng•h/ml, and bioavailability of 74.3% [43]. In the H22 xenografted mice model, hybrid 26 (relative tumor growth ratio/T/C: 27% at 60 mg/kg through oral gavage) significantly reduced the tumor growth without loss of body weight, and the in vivo efficacy was superior to that of LY-3200882 (T/C: 57% at 60 mg/kg through oral gavage). Moreover, hybrid 26 (IC50: >30 μM) did not show inhibitory activity to human ether-à-go-go-related gene (hERG) channel, indicating its excellent safety profile. Accordingly, hybrid 26 warranted further preclinical evaluations for liver cancer therapy.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of sulfonamide–pyrazole/indazole hybrids 26–35.

Sulfonamide–1,2,3-triazole-pyrazole hybrid 27 (IC50: 3.2 μM, SRB assay) was comparable to celecoxib (IC50: 2.56 μM) against MCF-7 cancer cells [44], and the SAR demonstrated that oxime on the pyrazole moiety was critical for the activity as evidenced by that hybrid 28 (IC50: 12.40 μM, MTT assay) showed considerable antiproliferative activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells [45]. Moreover, hybrid 27 displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 378.9 μM) toward normal WI-38 cells and was a promising dual inhibitor of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, IC50: 0.04 μM) and 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX, IC50: 1.29 μM). Mechanistically, hybrid 27 caused cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase and induced apoptosis through increasing expression levels of caspase-9 and Bax and decreasing expression level of Bcl-2. The molecular docking studies revealed that hybrid 27 lodged into the inner hydrophobic cleft of the active site of COX-2, and accommodated into the hydrophobic U-shaped cavity of 15-LOX active site. Hybrid 27 (LD50: 61.67 mg/kg) demonstrated lower in vivo toxicity than 5-fluorouracil (LD50: 57.2 mg/kg) in newborn BALB/c mice, revealing its good safety profile. In the MCF-7 xenografted mice model, hybrid 27 (TGI: ∼75% at a dose of 23 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection) was equal to 5-fluorouracil (TGI: ∼75% at a dose of 23 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection) in terms of inhibition of tumor growth, and mice treated with hybrid 27 only showed slightly decrease (8.3%) in body weight, while 5-fluorouracil led to 21.7% body weight loss. Collectively, hybrid 27 was a potent preclinical candidate for the exploration of therapeutic interventions against breast cancer.

Sulfonamide–pyridine–pyrazole hybrid 29 (IC50: 1.23–2.22 μM, MTT assay) possessed potent antiproliferative activity against RPMI-8226, SR, HOP-92, HL-60, MOLT-4, SK-MEL-5, PC3, COLO-205 and T-47D cancer cell lines and displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 44.02 and 87.68 μM) toward normal RAW 264.7 macrophages and primary epidermal keratinocytes cell lines [46]. Hybrid 29 (IC50: 0.38–1.38 μM) showed considerable inhibitory effects against c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1), JNK2, p38a and V600EBRAF and could cause cell cycle arrest at G1/S phase. In case of JNK1, hybrid 29 was docked in the active site of JNK1 and formed two hydrogen bonds; regarding JNK2, hybrid 29 showed four hydrogen bonds; for p38a, hybrid 29 possessed two hydrogen bonds in addition to one interaction between phenyl ring of sulfonamide and Val 38; for V600EBRAF, hybrid 29 showed three hydrogen bonds.

The SAR revealed that pyridine was not critical for the antiproliferative activity, and sulfonamide–pyridine–pyrazole hybrids 30a,b (GI50: 88–780 nM and 25–162 nM respectively, SRB assay) exhibited pronounced antiproliferative activity against H460, H82, U251, U937, KM12, COLO205, MV4–11, MDA-MB-231, HCT-116, HT29, ES2, OVCAR5, OAW28, OV90, COV318 and COV504 cancer cell lines [47]. Mechanistically, hybrid 30a reduced the phosphorylation of retinoblastoma at Ser807/811, arrested the cells at the G2/M phase and induced apoptosis. The docking results revealed that hybrid 30a may bound to the ATP binding pocket of CDK2 via two hydrogen bonds with Leu83 of the kinase, while the 2-amino group of the pyrimidine ring showed a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl of Leu83, and the pyrimidinyl-N1 formed a hydrogen bond with the NH of the same amino acid residue.

Sulfonamide–pyrazole hybrids 31a,b (IC50: 4.63 and 8.90 μM, MTT assay) were more potent than celecoxib (IC50: 30 μM) against MCF-7 breast cancer cells and could simultaneously inhibit prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production in LPS-activated murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells and suppress cell cycle progression of MCF-7 cells at G2/M or G0/G1 phases [48]. Further studies showed that hybrid 31a induced apoptosis via caspase-3 activation. The molecular docking studies of hybrid 31a with tubulin revealed that Asn101, Ala250, Asn258, Met259, Lys352 were the key residues involved in hydrogen bond formation and an array of non-covalent interactions were observed as contributed by Val238, Cys241 (Halogen); Leu248, Leu255 and Ala316 (Pi–alkyl bond type); Lys254 and Val351 (carbon hydrogen bond). The SAR illustrated that phenyl ring on the pyrazole moiety seems to be beneficial for the activity as evidenced by that hybrid 32 (IC50: 33–127 μM, MTT assay) only possessed weak to moderate antiproliferative activity against HCT-116, MCF-7 and K562 cancer cell lines [49].

FD223 (33, IC50: 0.87–5.82 μM, MTT assay), a sulfonamide–pyridine–7-azaindazole hybrid, showed promising antiproliferative activity against HL-60, MOLM-16, EOL-1 and KG-1 acute myeloid leukemia cell lines and displayed profound inhibitory activity (IC50: 1.0 nM) against PI3Kδ [50]. In the hinge region of PI3Kδ, the 7-azaindazole of FD223 formed two hydrogen bonds with the residue Val828, and the pyridine nitrogen interacted with the residues Asp787 and Asp911 through the crystalline-water-mediated hydrogen bonds in the affinity pocket. Besides, the sulfonamide moiety also formed a hydrogen bond with the conserved catalytic lysine (Lys779). The pharmacokinetic studies indicated that FD223 (10 mg/kg, oral administration) possessed favorable pharmacokinetic properties with t1/2 of 3.74 h, Cmax of 1104 ng/ml, AUC0-∞ of 9217 h•ng/ml and oral bioavailability of 17.6%. In the MOLM-16 xenografted mice model, FD223 (40 mg/kg, oral administration) showed potent in vivo efficacy with TGI value of 49% without significantly change in body weight. After oral administration of FD223 at a dose of 90 mg/kg, all mice grew normally, and no significant behavioral abnormality or injury in the major organs including heart, liver, spleen, lung and kidney was observed, demonstrating its good safety profile. Taken together, FD223 has potential for further development as a promising PI3Kα inhibitor for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia.

Sulfonamide–indazole hybrid 34 (IC50: 2.66 and 2.19 μM, MTT assay) exhibited excellent antiproliferative activity against A549 and HCT-116 cancer cell lines and was non-toxic (IC50: >50 μM) toward normal HEK-293 and HaCaT cell lines [51]. Mechanistically, hybrid 34 caused cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 phase with a concomitant increase in p53 and p21 protein levels. In addition, hybrid 34 resulted in ATP depletion and disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential cancer cell lines. Hybrid 35 (IC50: 6.62–12.3 μM, MTT assay) was comparable to AT-101 (IC50: 6.02–7.71 μM) against PC-3, MDA-MB-231 and K562 cancer cell lines and was non-toxic (IC50: >50 μM) toward normal LO2 cells [52]. Mechanistically, hybrid 35 could effectively induce apoptosis through specifically inhibition of myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1 (Mcl-1) and activation of caspase-3. The molecular docking studies demonstrated that the 3,4-dichlorobromobenzyl fragment in hybrid 35 could occupy the critical P2 pocket of Mcl-1, and a total of five hydrogen bonds between the acylsulfonamide group, 3-nitro-4-chlorophenyl of hybrid 35 and Mcl-1 protein may contribute to its promising binding affinity to Mcl-1 protein.

6. Sulfonamide–thiazole/fused thiazole hybrids

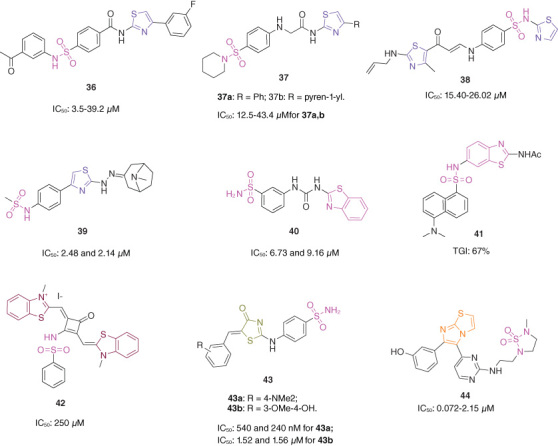

D8 (Figure 5; 36, IC50: 3.5–39.2 μM), a sulfonamide–thiazole hybrid, showed considerable antiproliferative activity against H23, BT-20, PC9, NCI-H1975, HCT-116, HCC827, Panc-1, ZR-75-1, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cancer cell lines and displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 52.9 μM) toward normal MCF-10A breast cells [53]. D8 (IC50: 2.8 μM) could inhibit phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH) and possessed good metabolic stability (t1/2: 106.0 and 87.2 min, respectively) in human and mouse liver microsomes. The molecular docking studies indicated that 4-(3-fluorophenyl)thiazole in D8 was clamped by a hydrophobic pocket formed with T207, P208, L210, T213, L216, Y174, P176, I177, L151 and L200, NH-group acted as a donor to form a hydrogen bond with D175, and one hydrogen bond was formed between the sulfonamide NH-group and the side chain of R158. D8 (3.0 mg/kg, oral administration) also possessed excellent pharmacokinetic properties with t1/2 of 4.74 h, Cmax of 8842 ng/ml, AUC0-∞ of 94386 ng•h/ml and oral bioavailability of 82.0%. In the PC9 xenografted mouse model, D8 (intraperitoneal injection) significantly delayed the tumor growth with TGI of 68.9% at a dose of 25 mg/kg and didn't cause noticeable loss in body weight or histopathological abnormalities in liver, lung or kidney.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of sulfonamide–thiazole/fused thiazole hybrids 36–44.

Sulfonamide–thiazole hybrids 37a,b (IC50: 12.5–43.4 μM, MTT assay) showed moderate antiproliferative activity against A549 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines, and the activity was not inferior to that of taxol (IC50: 40 μM) against MDA-MB-231 cancer cells [54]. In addition, hybrids 37a,b (IC50: 257 and 1966 μM) displayed low cytotoxicity toward normal WI-38 cells and could induce apoptosis. The molecular docking studies indicated that hybrid 37a interacted with the active site through formation of hydrogen bond between the sulfonamide group and Asn64, whereas hybrid 37b interacted with the active site through formation of two π–hydrogen bonds between phenyl ring next to the sulfonyl group and Phe34 and Ile60. The SAR illustrated that introduction of the second thiazole moiety could not increase the activity, and hybrid 38 (IC50: 15.40–26.02 μM, MTT assay) also displayed moderate antiproliferative activity against MCF-7, HCT-116 and HepG2 cancer cell lines [55]; incorporation of hydrazone fragment into thiazole moiety could enhance the antiproliferative activity as evidenced by that hybrid 39 (IC50: 2.48 and 2.14 μM, MTT assay) was more potent than chlorambucil (IC50: 4.71 and 2.92 μM) against MDA-MB-231 and B16-F10 cancer cell lines [56].

Sulfonamide–urea–benzothiazole hybrid 40 (IC50: 6.73 and 9.16 μM, MTT assay) was not inferior to doxorubicin (IC50: 7.31 and 6.52 μM) against T-47D and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines [57], whereas hybrid 41 (0.7 mg/kg/day, intraperitoneal injection) reduced 67% tumor volume in the A375 xenografted mouse model without apparent signs of acute toxicity and behavioral change [58]. Further study revealed that incorporation of the second benzothiazole moiety was favorable to the antiproliferative activity, and SQ-D2 (42, IC50: 250 nM, CCK-8 assay) showed decent antiproliferative activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells [59]. Mechanistically, SQ-D2 after the light irradiation could generate the ROS, leading to the cell apoptosis. In the MCF-7 xenografted mice model, SQ-D2 (0.15 mg/kg, intratumorally injection) in the irradiation reduced 83% tumor volume without loss of body weight.

Sulfonamide–thiazolone hybrid 43a (IC50: 540 and 240 nM, SRB assay) was more potent than doxorubicin (IC50: 1.5 and 0.9 μM) and 5-fluorouracil (IC50: 1.7 and 38.5 μM) against MCF-7 and HepG2 cancer cell lines and was non-toxic (IC50: >100 μM) toward normal MCF-10A breast cells [60], whereas hybrid 43b (IC50: 1.52 and 1.56 μM, MTT assay) was superior to staurosporine (IC50: 5.89 and 7.67 μM) against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines and displayed relatively low cytotoxicity (IC50: 26.1 μM) toward normal MCF-10A breast cells [61]. Mechanistically, hybrid 43a caused cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase and induced apoptosis. The docking studies revealed that hybrids 43a,b fitted accurately within the active site of CA IX involving some interactions including coordination bonds and hydrogen bonds, sulfonamide moiety aligned toward His94, His96, His119, Thr200, Thr201, Tyr11 and Glu106 amino acids residues, while the benzylidene moieties were extended toward Arg129, Val130, Asp131 and Leu134 residues forming some hydrogen bond interactions.

Sulfonamide–imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole hybrid 44 (IC50: 0.072–2.15 μM, MTT assay) exhibited excellent antiproliferative activity against a panel of MDA-MB-231, SK-MEL-2, SK-MEL-5, SK-MEL-28, LOX-IMVI, MALME-3M, M14, UACC-62 and UACC-256 cancer cell lines and displayed low cytotoxicity (IC50: 45.00 and 49.56 μM) toward normal L132 and BJ1 cell lines [62–64]. Hybrid 44 formed four hydrogen bonds: one between the 3-hydroxyphenyl group at C-6 position of the imidazothiazole nucleus and Ser 455, two between one oxygen from the sulfonamide group and Asp 594 and Lys 483, and one between protonated sulfur of the imidazothiazole nucleus and Ser535. Further studies showed that no sign of toxicity was observed in hybrid 44-treated mice even at a dose of 250 mg/kg, and hybrid 44 (t1/2: >120 min) possessed good metabolic stability in human and rat liver microsomes. In the A375 xenografted mice model, hybrid 44 (50 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection) showed reduction of tumor volume by 75% and suppression of tumor weight by 68.7%.

7. Conclusion

Multidrug resistance is a major obstacle to successful cancer therapy and is crucial to cancer metastasis and relapse, highlighting the urgent need to explore novel anticancer chemotherapeutics. Azole–sulfonamide hybrids with structural and mechanism diversity possess profound activity against various cancers including drug-resistant forms through multi-target therapy and can reduce side effects caused by the corresponding pharmacophores. Thus, azole–sulfonamide hybrids represent a fertile source for discovery of novel therapeutic agents for clinical deployment in the control and eradication of cancers.

The purpose of this review is to summarize the current scenario of anticancer therapeutic potential, structure–activity relationships, pharmacokinetic properties, toxicity and mechanisms of action of azole–sulfonamide hybrids, covering articles published from 2020 onward. In particular, hybrids 9, 13a,b, 14a,b, 16a–c, 18a, 20a–c, 21, 23a,b, 24, 30a,b, 42 and 43a exhibited pronounced antiproliferative activity against various cancer cell lines with IC50 or GI50 in nanomolar level, revealing their potential to fight against diverse cancers; hybrids 8a,b were active against drug-resistant cancer cells, demonstrating their potential to overcome drug resistance; hybrids 1, 8a, 13a, 15, 16a, 18a, 21, 26, 27, 33, 36, 41, 42 and 44 possessed excellent in vivo efficacy, indicating their potential to serve as useful candidates for further preclinical evaluations. Considering all the reports of this review collectively, it can be concluded that azole and sulfonamide moieties are important pharmacophores and can be combined into one molecule with various linkers for the design and synthesis of novel anticancer lead compounds or candidates for screening.

8. Future perspective

Further studies can focus on rational structural modifications of existing azole–sulfonamide hybrids with promising anticancer activity to enhance their activity; further preclinical evaluations of azole–sulfonamide hybrids with profound anticancer efficacy to identify more clinical candidates.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Reference

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.World Health Organization . Latest global cancer data: cancer burden rises to 19.3 million new cases and 10.0 million cancer deaths in 2020. Available at: www.iarc.who.int/fr/news-events/latest-global-cancer-data-cancer-burden-rises-to-19-3-million-new-cases-and-10-0-million-cancer-deaths-in-2020/ (Accessed date: Apr. 2024).

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer . Cancer tomorrow. https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/graphic-isotype?type=0&population=900&mode=population&sex=0&cancer=39&age_group=value&apc_male=0&apc_female=0 (Accessed date: 2024 Apr). [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Agency for Research on Cancer . World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN 2018. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/39-All-cancers-fact-sheet.pdf (Accessed date: 2024 Apr). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhushan A, Gonsalves A, Menon JU. Current state of breast cancer diagnosis, treatment, and theranostics. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(5):e723. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13050723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hulvat MC. Cancer incidence and trends. Surg Clin N Am. 2020;100(3):469–481. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A review regarding cancer incidence and trends.

- 7.Anand U, Dey A, Chandel AKS, et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Gen Dis. 2023;10(4):1367–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2022.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A review regarding current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics.

- 8.Rong X, Liu C, Li X, et al. Recent advances in chemotherapy-based organic small molecule theranostic reagents. Coordin Chem Rev. 2022;472:e214808. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; •• A review regarding organic small molecule theranostic reagents.

- 9.Aboud K, Meissner M, Ocen J, et al. Cytotoxic chemotherapy: clinical aspects. Medicine. 2023;51(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2022.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; •• A review regarding clinical aspects of cytotoxic chemotherapy.

- 10.Emran TB, Shahriar A, Mahmud AR, et al. Multidrug resistance in cancer: understanding molecular mechanisms, immunoprevention and therapeutic approaches. Front Oncol. 2022;12:e891652. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.891652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A review regarding molecular mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer, immunoprevention and therapeutic approaches.

- 11.Prasher P, Sharma M, Zacconi F, et al. Synthesis and anticancer properties of ‘Azole’ based chemotherapeutics as emerging chemical moieties: a comprehensive review. Curr Org Chem. 2021;25(6):654–668. doi: 10.2174/1385272824999200820152501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; •• A review regarding azole-based anticancer chemotherapeutics.

- 12.Kamal R, Kumar A, Kumar R. Synthetic strategies for 1,4,5/4,5-substituted azoles: a perspective review. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2023;60(1):5–17. doi: 10.1002/jhet.4537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; • A review regarding synthetic strategies for 1,4,5/4,5-substituted azoles.

- 13.Culletta G, Tutone M, Zappalà M, et al. Sulfonamide moiety as “molecular chimera” in the design of new drugs. Curr Med Chem. 2023;30(2):128–163. doi: 10.2174/0929867329666220729151500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan Y, Fang G, Chen H, et al. Sulfonamide derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents and their SARs elucidation. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;226:e113837. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A review regarding sulfonamide derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents.

- 15.Hamed FM, Hassan BA, Abdulridha MM. The antitumor activity of sulfonamides derivatives: review. Int J Pharm Res. 2020;12:2512–2519. doi: 10.31838/ijpr/2020.SP1.390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rakesh A, Wang SM, Leng J, et al. Recent development of sulfonyl or sulfonamide hybrids as potential anticancer agents: a key review. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2018;18(4):488–505. doi: 10.2174/1871520617666171103140749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang Y, Tan Q, Zhou H, et al. Discovery and optimization of 2-(trifluoromethyl)benzimidazole derivatives as novel ferroptosis inducers in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;245:e114905. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Meguid EAA, El-Deen EMM, Nael MA, et al. Novel benzimidazole derivatives as anti-cervical cancer agents of potential multi-targeting kinase inhibitory activity. Arab J Chem. 2020;13(12):9179–9195. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.10.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkhaldi AAM, Al-Sanea MM, Nocentini A, et al. 3-Methylthiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazole-benzenesulfonamide conjugates as novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitors endowed with anticancer activity: design, synthesis, biological and molecular modeling studies. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;207; e112745. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali EMH, Abdel-Maksoud MS, Ammar UM, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel imidazole derivatives possessing terminal sulphonamides as potential BRAFV600E inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2021;106:e104508. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelazeem AH, Abdelhamid AA, Al-Wahaibi LH, et al. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and computational studies of novel tri-aryl imidazole-benzene sulfonamide hybrids as promising selective carbonic anhydrase IX and XII inhibitors. Molecules. 2021;26(16):e4718. doi: 10.3390/molecules26164718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alghamdi EM, Alamshany ZM, El-Hamd MA, et al. Anticancer activities of tetrasubstituted imidazole-pyrimidine-sulfonamide hybrids as inhibitors of EGFR mutants. ChemMedChem. 2023;18(8):e202200641. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202200641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almatary AM, Eisa HMH, Husseiny WME, et al. Nitroimidazole-sulfonamides as carbonic anhydrase IX and XII inhibitors targeting tumor hypoxia: design, synthesis, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation. J Mol Struct. 2022;1264:e133260. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.133260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balandis B, Mickevičius V, Petrikaitė V. Exploration of benzenesulfonamide-bearing imidazole derivatives activity in triple-negative breast cancer and melanoma 2D and 3D cell cultures. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(11):e1158. doi: 10.3390/ph14111158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bazanov DR, Pervushin NV, Savin EV, et al. Sulfonamide derivatives of cis-imidazolines as potent p53-MDM2/MDMX protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Med Chem Res. 2021;30(12):2216–2227. doi: 10.1007/s00044-021-02802-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xin L, Min J, Hu H, et al. Structure-guided identification of novel dual-targeting estrogen receptor α degraders with aromatase inhibitory activity for the treatment of endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Eur J Med Chem. 2023;253:e115328. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2023.115328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu B, Xu Y, Lu Y, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of sulfonamides inhibitors of XPO1 displaying activity against multiple myeloma cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;235:e114257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elsawi AE, Elbadawi MM, Nocentini A, et al. 1,5-Diaryl-1,2,4-triazole ureas as new SLC-0111 analogues endowed with dual carbonic anhydrase and VEGFR-2 inhibitory activities. J Med Chem. 2023;66(15):10558–10578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandramohan V, Govindaiah S, Khan G, et al. Synthesis, biological screening, in silico study and fingerprint applications of novel 1,2,4-triazole derivatives. J Heterocyclic Chem. 2020;57:2010–2023. doi: 10.1002/jhet.3929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun J, Baker JR, Russell CC, et al. Cytotoxic 1,2,3-triazoles as potential leads targeting the S100A2-p53 complex: synthesis and cytotoxicity. ChemMedChem. 2021;16(18):2864–2881. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C, Nan Y, Xia Z, et al. Discovery of novel hydroxyamidine derivatives as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 inhibitors with in vivo anti-tumor efficacy. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30:e127038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X, Sun P, Wang J, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 1,2,5-oxadiazole-3-carboximidamide derivatives as novel indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;189:e112059. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue D, Xu Y, Kyani A, et al. Discovery and lead optimization of benzene-1,4-disulfonamides as oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2022;65:343–368. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shamsi F, Hasan P, Queen A, et al. Synthesis and SAR studies of novel 1,2,4-oxadiazole-sulfonamide based compounds as potential anticancer agents for colorectal cancer therapy. Bioorg Chem. 2020;98:e103754. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Y, Han Y, Zhang F, et al. Design, Synthesis, and biological evaluation of imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine derivatives as novel PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2020;63:3028–3046. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnes KL, Sisco E. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel 1,3-oxazole sulfonamides as tubulin polymerization inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2021;12(6):1030–1037. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao H, Li Z, Wang K, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of sulfonamide methoxypyridine derivatives as novel PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:e461. doi: 10.3390/ph16030461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Luo Y, Yin H, et al. Design, synthesis, and antitumor activity evaluation of novel acyl sulfonamide spirodienones. Bioorg Med Chem. 2022;60:e116626. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2022.116626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Almalki AJ, Ibrahim TS, Taher ES, et al. Synthesis, antimicrobial, anti-virulence and anticancer evaluation of new 5(4H)-oxazolone-based sulfonamides. Molecules. 2022;27:e671. doi: 10.3390/molecules27030671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang MF, Luo XY, Zhang C, et al. Design, synthesis and pharmacological characterization of N-(3-ethylbenzo[d]isoxazol-5-yl) sulfonamide derivatives as BRD4 inhibitors against acute myeloid leukemia. Acta Pharm Sin. 2022;43:2735–2748. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00881-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dende SK, Korupolu RB, Leleti KR. Design and synthesis of sulfonamide-attached 2-(isoxazole-3-yl)-1H-imidazoles as anticancer agents. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:7919–7922. doi: 10.1002/slct.202001449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaickelioniene R, Petrikaite V, Vaskeviciene I, et al. Synthesis of novel sulphamethoxazole derivatives and exploration of their anticancer and antimicrobial properties. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(3):e0283289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0283289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan B, Zhang X, Quan X, et al. Design, synthesis and biological activity evaluation of novel 4-((1-cyclopropyl-3-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)oxy)pyridine-2-yl)amino derivatives as potent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) type I receptor inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30:e127339. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abd El Wahab SM, Alaaeddine R, Allam RM, et al. Expanding the anticancer potential of 1,2,3-triazoles via simultaneously targeting cyclooxygenase-2,15-lipoxygenase and tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;200:e112439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elgogary SR, Khidre ER, El-Telbani EM. Regioselective synthesis and evaluation of novel sulfonamide 1,2,3-triazole derivatives as antitumor agents. J Iran Chem Soc. 2020;17(4):765–776. doi: 10.1007/s13738-019-01796-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdel-Maksoud MS, Hassan RM, El-Azzouny AAS, et al. Anticancer profile and anti-inflammatory effect of new N-(2-((4-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)pyridine sulfonamide derivatives. Bioorg Chem. 2021;117:e105424. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fanta BS, Mekonnen L, Basnet SKC, et al. 2-Anilino-4-(1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)pyrimidine-derived CDK2 inhibitors as anticancer agents: design, synthesis & evaluation. Bioorg Med Chem. 2023;80:e117158. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2023.117158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ngo QA, Thi THN, Pham MQ, et al. Antiproliferative and antiinfammatory coxib-combretastatin hybrids suppress cell cycle progression and induce apoptosis of MCF7 breast cancer cells. Mol Diversity. 2021;25:2307–2319. doi: 10.1007/s11030-020-10121-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Culletta G, Allegra M, Almerico AM, et al. In silico design, synthesis and biological evaluation of anticancer arylsulfonamide endowed with anti-telomerase activity. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15(1):e82. doi: 10.3390/ph15010082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang C, Xu C, Li Z, et al. Bioisosteric replacements of the indole moiety for the development of a potent and selective PI3Kδ inhibitor: design, synthesis and biological evaluation. Eur J Med Chem. 2021;223:e113661. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bułakowska A, Heldt M, Sławiński J, et al. Novel N-(aryl/heteroaryl)-2-chlorobenzenesulfonamide derivatives: synthesis and anticancer activity evaluation. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:e104309. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wan Y, Li Y, Yan C, et al. Discovery of novel indazole-acylsulfonamide hybrids as selective Mcl-1 inhibitors. Bioorg Chem. 2020;104:e104217. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao D, Tang S, Cen Y, et al. Discovery of novel drug-like PHGDH inhibitors to disrupt serine biosynthesis for cancer therapy. J Med Chem. 2023;66(1):285–305. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hussein EM, Al-Rooqi MM, Elkhawaga AA, et al. Tailoring of novel biologically active molecules based on N4-substituted sulfonamides bearing thiazole moiety exhibiting unique multi-addressable biological potentials. Arab J Chem. 2020;13(5):5345–5362. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bondock S, Albormani O, Fouda AM. Expedient synthesis and antitumor evaluation of novel azaheterocycles from thiazolylenaminone. Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds. 2023;43(3):2123–2143. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2022.2039236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piechowska K, Mizerska-Kowalska M, Zdzisińska B, et al. Tropinone-derived alkaloids as potent anticancer agents: synthesis, tyrosinase inhibition, mechanism of action, DFT calculation, and molecular docking studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):e9050. doi: 10.3390/ijms21239050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Warhi T, Elbadawi MM, Bonardi A, et al. Design and synthesis of benzothiazole-based SLC-0111 analogues as new inhibitors for the cancer-associated carbonic anhydrase isoforms IX and XII. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2022;37(1):2635–2643. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2022.2124409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millet A, Filho MS, Hamouda-Tekaya N, et al. Development and in vivo evaluation of fused benzazole analogs of anti-melanoma agent HA15. Future Med Chem. 2021;13(14):1157–1173. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2021-0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li JH, You PD, Lu F, et al. Single aromatics sulfonamide substituted dibenzothiazole squaraines for tumor NIR imaging and efficient photodynamic therapy at low drug dose. J Photochem Photobiol Biol. 2023;240:e112653. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2023.112653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nissan YM, Mohamed KO, Ahmed WA, et al. New benzenesulfonamide scaffold-based cytotoxic agents: design, synthesis, cell viability, apoptotic activity and radioactive tracing studies. Bioorg Chem. 2020;96:e103577. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nemr MTM, AboulMagd AM, Hassan HM, et al. Design, synthesis and mechanistic study of new benzenesulfonamide derivatives as anticancer and antimicrobial agents via carbonic anhydrase IX inhibition. RSC Adv. 2021;11:26241–26257. doi: 10.1039/D1RA05277B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abdel-Maksoud MS, El-Gamal MI, Lee BS, et al. Discovery of new imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole derivatives as potent Pan-RAF inhibitors with promising in vitro and in vivo anti-melanoma activity. J Med Chem. 2021;64:6877–6901. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ammar UM, Abdel-Maksoud MS, Ali EMH, et al. Structural optimization of imidazothiazole derivatives affords a new promising series as B-Raf V600E inhibitors; synthesis, in vitro assay and in silico screening. Bioorg Chem. 2020;100:e103967. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ammar UM, Abdel-Maksoud MS, Mersal KI, et al. Modification of imidazothiazole derivatives gives promising activity in BRaf kinase enzyme inhibition; synthesis, in vitro studies and molecular docking. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2020;30:e127478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]