Abstract

Background and Objectives

Plasma β-amyloid-1–42/1–40 (Aβ42/40), phosphorylated-tau (P-tau), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light (NfL) have been widely examined in Alzheimer disease (AD), but little is known about their reflection of copathologies, clinical importance, and predictive value in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). We aimed to evaluate associations of these biomarkers with CSF amyloid, cognition, and core features in DLB.

Methods

This cross-sectional multicenter cohort study with prospective component included individuals with DLB, AD, and healthy controls (HCs), recruited from 2002 to 2020 with an annual follow-up of up to 5 years, from the European-Dementia With Lewy Bodies consortium. Plasma biomarkers were measured by single-molecule array (Neurology 4-Plex E kit). Amyloid status was determined by CSF Aβ42 concentrations, and cognition was assessed by Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Biomarker differences across groups, associations with amyloid status, and clinical core features were assessed by analysis of covariance. Associations with cognitive impairment and decline were assessed by linear regression and linear mixed-effects models.

Results

In our cohort consisting of 562 individuals (HC n = 89, DLB n = 342, AD n = 131; 250 women [44.5%], mean [SD] age of 71 [8] years), sex distribution did not differ between groups. Patients with DLB were significantly older, and had less years of education and worse baseline cognition than HC, but not AD. DLB participants stratified for amyloid status differed significantly in plasma Aβ42/40 ratio (decreased in amyloid abnormal: β = −0.008, 95% CI −0.016 to −0.0003, p = 0.01) and P-tau (increased in amyloid abnormal, P-tau181: β = 0.246, 95% CI 0.011–0.481; P-tau231: β = 0.227, 95% CI 0.035–0.419, both p < 0.05), but not in GFAP (β = 0.068, 95% CI −0.018 to 0.153, p = 0.119), and NfL (β = 0.004, 95% CI −0.087 to 0.096, p = 0.923) concentrations. Higher baseline GFAP, NfL, and P-tau concentrations were associated with lower MMSE scores in DLB, and GFAP and NfL were associated with a faster cognitive decline (GFAP: annual change of −2.11 MMSE points, 95% CI −2.88 to −1.35 MMSE points, p < 0.001; NfL: annual change of −2.13 MMSE points, 95% CI −2.97 to −1.29 MMSE points, p < 0.001). DLB participants with parkinsonism had higher concentrations of NfL (β = 0.08, 95% CI 0.02–0.14, p = 0.006) than those without.

Discussion

Our study suggests a possible utility of plasma Aβ42/40, P-tau181, and P-tau231 as a noninvasive biomarkers to assess amyloid copathology in DLB, and plasma GFAP and NfL as monitoring biomarkers for cognitive symptoms in DLB.

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is considered the most frequent type of dementia after Alzheimer disease (AD) in the elderly.1 It is clinically characterized by cognitive decline and visual hallucinations, cognitive fluctuations, sleep disturbances, parkinsonism, and autonomic dysfunction.2 Survival after diagnosis has shown to be shorter for patients with DLB when compared with AD. In DLB, survival times of about 4 years after diagnosis have been reported; however, large heterogeneity of clinical presentation and progression, and copathologies can hamper prediction of the disease course over time.3-6

The neuropathologic hallmark of DLB is the accumulation of phosphorylated α-synuclein (α-syn) aggregates in intracytoplasmic inclusions, so-called Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, throughout the brain.1 In addition, concomitant AD neuropathology is observed in a substantial portion of patients with DLB,7 and there is considerable overlap in both clinical and pathologic features between DLB and AD and Parkinson disease (PD). Furthermore, pathologic processes other than protein aggregation are present in DLB and probably contribute to neurodegeneration and disease progression. For instance, accumulating evidence suggests that α-syn, but also AD-pathology, evokes neuroinflammation in DLB.8 Therefore, there is a need for combined biomarker assessment reflecting these different disease processes to define the effect of these processes on diagnosis, heterogeneity in disease manifestation, and disease progression.

CSF analyses and PET imaging are considered state of the art for detecting AD pathology, but recent developments have led to plasma biomarkers for the detection of several cerebral pathologic processes with adequate accuracy. With current multiplex techniques, several biomarkers can be measured simultaneously in a single sample, greatly improving the possibilities to investigate the effect of different pathologies in a less invasive and time-consuming fashion.9

In numerous cohorts, blood-based core AD biomarkers correlated highly with CSF AD biomarkers in all stages of AD.10 In addition to core AD biomarkers (decreased β-amyloid [Aβ] 42/40 ratio and increased phosphorylated-tau [P-tau] concentrations), other more general biomarkers including neurofilament light (NfL) as a marker for neuroaxonal damage and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) reflecting reactive astrogliosis are elevated in both patients with DLB and AD compared with HC.11-13

Most studies analyze blood-based biomarkers with a main focus on AD, and therefore, less is known about the use of these biomarkers as early diagnostic and prognostic markers in DLB. Although some studies include a DLB group to evaluate the diagnostic performance of blood-based biomarkers for the differentiation of AD from DLB, sample sizes are rather moderate and studies of blood-based biomarkers in DLB specifically are scarce.14-16

The differential power of blood biomarkers to differentiate AD from DLB seems to be rather cohort-dependent.14 Although, in a previous study P-tau181 and GFAP have been found to be associated with CSF amyloid status, another study reported no association of any of the above-mentioned biomarkers with amyloid PET. Notably, both studies included rather small sample sizes (association with CSF amyloid: n = 31 amyloid normal (A−) vs n = 18 amyloid abnormal (A+); association with amyloid PET: n = 30 A− vs n = 29 A+).15,16

Recently, we demonstrated in a large European cohort that plasma concentrations of specific P-tau species (P-tau181 and P-tau231) are significantly higher in patients with DLB compared with healthy controls (HCs), but lower compared with AD.17 Furthermore, we found that plasma P-tau biomarkers are elevated in DLB participants with concordant amyloid copathology and are associated with cognitive decline in the whole DLB group. These results suggest that P-tau species are reflective of brain amyloid because it has been shown before in various AD cohorts18,19 and could play an important role in monitoring disease progression in patients with DLB. The next question is whether blood biomarkers reflecting amyloidosis and other neurodegenerative processes including neuroaxonal damage and reactive astrogliosis are associated with AD copathology, cognition, or core features in DLB.

In this study, we aimed to add to and put our previous findings on P-tau into context, by evaluating the association of the plasma biomarkers, Aβ42/40 ratio, NfL, and GFAP, all reflecting different disease processes, with AD copathology, clinical features, and progression of cognition in DLB, leveraging a large multicenter cohort from the European-Dementia With Lewy Bodies (E-DLB) consortium.

Methods

Study Population

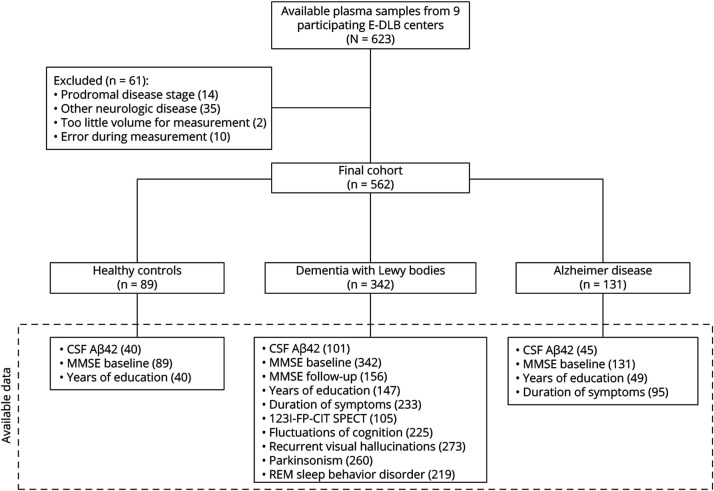

We retrospectively included participants from the E-DLB initiative cohort, from 9 different participating centers (eTable 1). Participants were referred between 2002 and 2020 from outpatient clinics for memory, movement disorders, geriatric medicine, psychiatry, or neurology as part of their diagnostic work-up.17,20 In total, plasma samples of 623 individuals were available from the E-DLB consortium. We excluded patients with other neurologic diseases, in prodromal disease stages, samples with too little volume, and those samples that gave an error during measurement. This resulted in a cohort of 562 individuals including 342 patients with probable DLB, 131 patients with AD, and 89 HC. Diagnoses of AD and probable DLB were harmonized between centers and made according to consensus guidelines2,21 based on all available clinical and diagnostic test results, by a multidisciplinary team, a group of at least 2 clinical experts, or by the treating physician. In 83 (79.0%) of 105 individuals with available 123I-N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane (123I-FP-CIT) SPECT scans, the clinical diagnosis of DLB was supported by abnormal dopamine transporter activity. Plasma biomarkers studied in this study were not used to support diagnoses. HC were individuals who presented at the respective clinic but did not have any neurologic disease. An overview of sample availability, cohort selection criteria, and data availability per diagnostic group is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of Sample Availability, Cohort Selection, and Data Availability Per Diagnostic Group.

The diagram depicts number of available samples, exclusion criteria, and number of participants in the final cohort, as well as available data for each diagnostic group.

Participating centers and sample contribution are listed in eTable 1. Cognitive impairment at baseline was assessed by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),22 and follow-up MMSE acquisition was performed in a subgroup of the patients with DLB at least once, and up to 5 years after the initial visit (n = 156 [5 years: n = 44, 4 years: n = 24, 3 years: n = 4, 2 years: n = 35, 1 year: n = 29], eFigure 1). Furthermore, in subsets of the DLB group, DLB core feature data were assessed at baseline as described previously23-26 and subsequently dichotomized as “present” or “not present” (fluctuations of cognition: n = 225 [present in n = 171, 76.0%], recurrent visual hallucinations: n = 273 [present in n = 149, 54.6%], parkinsonism: n = 260 [present in n = 161, 61.9%], and REM sleep behavior disorder [RBD]: n = 219 [present in n = 125, 57.1%]). Amyloid copathology was assessed in 101 of 342 patients with DLB (29.5% of the total DLB group) of whom 48 (47.5%) were defined abnormal (A+) by decreased CSF Aβ42 concentrations and 53 (52.5%) had normal CSF Aβ42 concentrations (A−). In the AD group, CSF Aβ42 concentrations were measured in 45 patients (34.4% of the total AD group) and CSF findings were in concordance with the clinical diagnosis for all patients with AD. All participants in the HC group with CSF amyloid data available (n = 40) were A−. Cutoff values and assays used for CSF Aβ42 measurements and baseline cohort characteristics for those individuals with CSF Aβ42 assessment are listed in eTables 2 and 3. Information on the duration of experienced symptoms was available for 233 patients with DLB and 95 patients with AD, while information on years of education was available for 147 patients with DLB, 49 patients with AD, and 40 HC.

Plasma Biomarkers

Information about plasma collection and sample handling is reported in eTable 2. Concentrations of Aβ40, Aβ42, GFAP, and NfL in plasma were measured on the Simoa HD-X Analyzer (Quanterix, Billerica, MA), with the commercially available Neurology 4-Plex E kit (Quanterix) at the Neurochemistry Laboratory, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, the Netherlands. The operating staff was blinded to the clinical data. Before measurement, samples were centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 minutes. Samples were measured across 3 runs in singlicate. Repeatability and intermediate precision were determined based on 3 quality controls and fell within the accepted range CV% <15%, for all markers (mean CV% [SD] repeatability, Aβ40: 2.7% [0.7%], Aβ42: 4.2% [1.4%], GFAP 8.2% [4.3%], NfL 5.6% [0.9%]; mean CV% [SD] intermediate precision, Aβ40: 3.3% [0.7%], Aβ42: 6.7% [0.5%], GFAP: 9.7% [3.6%], NfL: 6.7% [0.5%]). Plasma P-tau181 and P-tau231 were measured as described previously.17

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with R version 4.0.3.27 All tests were 2-tailed, corrected for multiple testing by Bonferroni correction, and the significance level was set to α = 0.05. Distributions of variables and model residuals were assessed by visual examination and the Shapiro-Wilk test (pastecs R package28). To achieve a normal distribution, P-tau 181, P-tau231, GFAP, and NfL were log10-transformed. Biomarker differences across diagnostic groups were assessed with analysis of covariance (car package), corrected for age and sex, and subsequent Tuckey post hoc test (multcomp R package29). Sex-related biomarker differences were assessed by the t test. Similarly, associations of plasma biomarkers with CSF amyloid status and DLB core features were assessed in the respective DLB subsets. Associations of plasma biomarkers with cognitive impairment at baseline were determined by linear regression analyses. Longitudinal cognitive decline was analyzed in patients with DLB with at least 1 follow-up measurement of MMSE scores, with linear mixed-effects models (lmerTest R package30) with random intercept and slope for each individual. First, we assessed the association of years of education with cognitive decline independently of plasma biomarkers values, by adding an interaction term of years of education and follow-up time. Subsequently, the association of plasma biomarker levels with cognitive decline was assessed by adding an interaction of plasma biomarkers and follow-up time, correcting the models for age, sex, and years of education. Model performances were assessed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and analysis of variance.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All participants provided written informed consent for their medical data and biomaterials to be used for research purposes, and the study was approved by the ethical committee of each participating center (eTable 1).

Data Availability

Data access to anonymized patient-level data can be requested from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Demographics

Baseline characteristics and plasma biomarker levels are summarized in Table 1. No difference in sex distribution was observed across diagnostic groups. The DLB and AD group did not differ significantly in age, years of education, duration of symptoms, or baseline MMSE scores, and no significant difference in years of education was observed between AD and HC. Patients with DLB and AD were significantly older than HC (mean age [SD]; HC: 67.4 [7.3], DLB: 71.6 [8.1], AD: 71.9 [7.9]) and had lower baseline MMSE scores. Participants with DLB had significantly less years of education compared with HC.

Table 1.

Baseline Cohort Characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | DLB (n = 342 [60.9%]) | AD (n = 131 [23.3%]) | HC (n = 89 [15.8%]) | p Value |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 144 (42.1) | 65 (49.6) | 41 (46.1) | 0.33 |

| Male | 198 (57.9) | 66 (50.4) | 48 (53.9) | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 71.6 (8.1) | 71.9 (7.9) | 67.4 (7.3) | <0.001a,b |

| Years of education, y, mean (SD)c | 10.1 (4.3) | 11.2 (3.5) | 12.6 (3.3) | 0.001a |

| Duration of symptoms, mo, median (IQR)d | 12.0 (3.0–36.0) | 7.0 (2.0–36.0) | NA | 0.11 |

| MMSE score, median (IQR) | 23.0 (18.4–26.3) | 23.0 (19.0–26.0) | 29.0 (27.0–30.0) | <0.001a,b |

| Abnormal CSF Aβ42 status, n (%)e | 48 (47.5) | 45 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Abnormal 123I-FP-CIT SPECT scan, n (%)f | 83 (79.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Plasma biomarkers | ||||

| Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, mean (SD) | 0.063 (0.015) | 0.056 (0.012) | 0.065 (0.014) | <0.001b,g |

| GFAP, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 173 (108–255) | 183 (133–246) | 99.3 (71.3–140) | <0.001a,b |

| NfL, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 27.8 (19.4–39.6) | 26.3 (19.4–35.1) | 16.1 (12.4–24.3) | <0.001a,b |

| P-tau181, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 15.9 (11.8–22.5) | 21.1 (16.1–26.5) | 10.6 (8.8–13.1) | <0.001a,b,g |

| P-tau231, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 11.4 (8.4–15.7) | 15.6 (11.0–20.0) | 7.6 (5.8–9.4) | <0.001a,b,g |

| Presence of DLB core features, n (%) | ||||

| Fluctuations of cognition (total n = 225) | 171 (76.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Recurrent visual hallucinations (total n = 273) | 149 (54.6) | NA | NA | NA |

| Parkinsonism (total n = 260) | 161 (61.9) | NA | NA | NA |

| REM sleep behavior disorder (total n = 219) | 125 (57.1) | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: 123I-FP-CIT = 123I-N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane; Aβ = β-amyloid; AD = Alzheimer disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; HC = healthy control; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NA = not available; NfL = neurofilament light; P-tau = phosphorylated tau.

Differences between DLB and HC.

Differences between AD and HC.

Years of education were assessed in 147 patients with DLB, 49 patients with AD, and 40 HC.

Duration from first cognitive or motor symptoms was assessed in 233 patients with DLB, and 95 patients with AD.

CSF Aβ42 status was assessed in 101 patients with DLB, 45 patients with AD, and 40 HC.

123I-FP-CIT SPECT scan was performed in 105 patients with DLB.

Differences between DLB and AD.

Plasma Biomarkers Across Diagnostic Groups

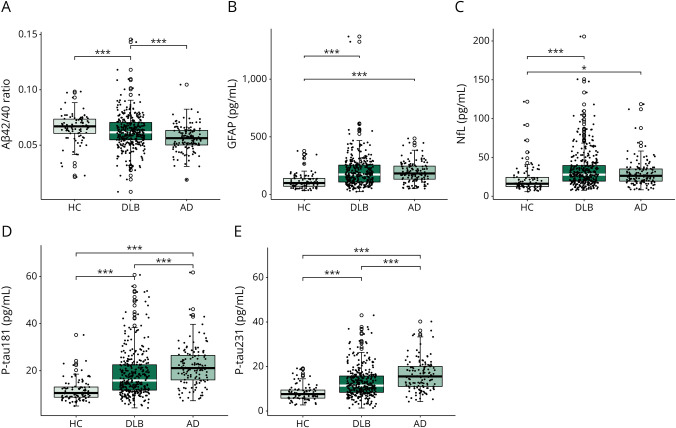

Biomarker differences across diagnostic groups are visualized in Figure 2. The Aβ42/40 ratio was significantly higher in the overall DLB group (β = 0.007, 95% CI 0.003–0.01, p < 0.001) and HC (β = 0.009, 95% CI 0.004–0.014, p < 0.001) compared with AD. GFAP and NfL concentrations were significantly higher in DLB (GFAP: β = 0.165, 95% CI 0.105–0.225, p < 0.001; NfL: β = 0.130, 95% CI 0.070–0.190, p < 0.001) and AD (GFAP: β = 0.168, 95% CI 0.099–0.237, p < 0.001; NfL: β = 0.086, 95% CI 0.016–0.155, p < 0.05) compared with HC. Both P-tau species were significantly increased in DLB (P-tau181: β = 0.368, 95% CI 0.245–0.491, p < 0.001; P-tau231: β = 0.379, 95% CI 0.242–0.517, p < 0.001) and AD (P-tau181: β = 0.579, 95% CI 0.437–0.720, p < 0.001; P-tau231: β = 0.635, 95% CI 0.476–0.793, p < 0.001) compared with HC, and higher in AD compared with DLB (P-tau181: β = 0.211, 95% CI 0.106–0.315, p < 0.001; P-tau231: β = 0.2552, 95% CI 0.138–0.372, p < 0.001). In the total cohort and within the AD group, GFAP was significantly higher in women than men (total cohort: t500.38 = −3.62, p = 0.001; AD: t127.33 = −3.64, p = 0.002). No other sex-related biomarker differences were observed.

Figure 2. Plasma Biomarkers Across Diagnostic Groups.

Plasma biomarker differences of Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (A), GFAP (B), NfL (C), P-tau181 (D), and P-tau231 (E) across diagnostic groups. Plasma Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was significantly higher in patients with DLB and HCs compared with patients with AD. Both plasma P-tau species were significantly higher in DLB compared with HC and significantly lower in DLB and HC compared with AD. Plasma GFAP and NfL concentrations were significantly higher in DLB and AD compared with HC. Plasma biomarker differences were assessed across groups by ANCOVA corrected for age and sex, and subsequent post hoc analysis by the Tukey post hoc test. p Values were adjusted for multiple comparison. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Aβ = β-amyloid; AD = Alzheimer disease; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; HC = healthy control; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NfL = neurofilament light; P-tau = phosphorylated tau.

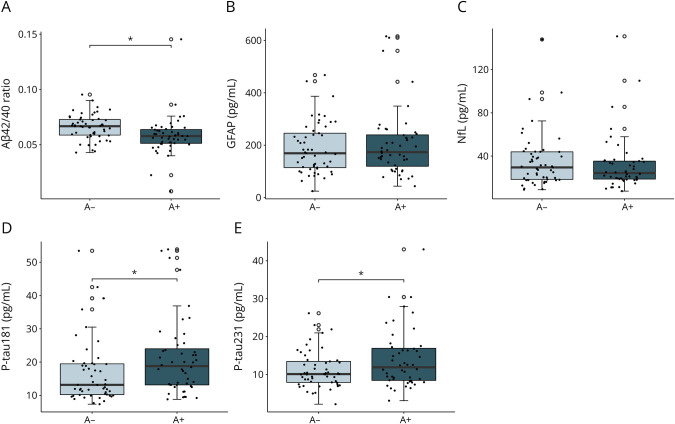

Association of Plasma Biomarkers With CSF Amyloid Status

DLB A+ patients had significantly lower plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, and higher P-tau181 and P-tau231 levels than DLB A− patients (Aβ42/40: β = −0.008, 95% CI −0.016 to −0.0003, p = 0.01; P-tau181: β = 0.246, 95% CI 0.011–0.481, p < 0.05; P-tau231: β = 0.227, 95% CI 0.035–0.419, p < 0.05), but no significant difference could be observed for GFAP (β = 0.068, 95% CI −0.018 to 0.153, p = 0.119) and NfL (β = 0.004, 95% CI −0.087 to 0.096, p = 0.923) (Figure 3). In DLB A+ individuals, the Aβ42/40 ratio was significantly lower (β = −0.007, 95% CI −0.014 to −0.0001, p = 0.045) compared with HC, but not significantly different from AD (β = 0.002, 95% CI −0.005 to 0.008, p = 0.937), and in DLB A− individuals, the Aβ42/40 ratio was significantly higher (β = 0.010, 95% CI 0.004–0.016, p < 0.001) compared with AD, but not significantly different from HC (β = 0.001, 95% CI −0.006 to 0.008, p = 0.995). The P-tau species were significantly increased in DLB A− (P-tau181: β = 0.272, 95% CI 0.065–0.479, p < 0.01; P-tau231: β = 0.274, 95% CI 0.044–0.504, p < 0.05) and DLB A+ (P-tau181: β = 0.518, 95% CI 0.308–0.728, p < 0.001; P-tau231: β = 0.478, 95% CI 0.242–0.714, p < 0.001) compared with HC, and significantly lower in DLB A− compared with AD (P-tau181: β = −0.304, 95% CI −0.496 to −0.111, p < 0.001; P-tau231: β = −0.359, 95% CI −0.573 to −0.145, p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Plasma Biomarkers in CSF Aβ42 Abnormal DLB Participants.

Plasma biomarkers Aβ42/40 ratio (A), GFAP (B), NfL (C), P-tau181 (D), and P-tau231 (E) in patients with DLB by CSF Aβ42 status (A+: n = 48; A−: n = 53). Plasma Aβ42/40 ratio was significantly lower, and both plasma P-tau species were significantly higher in DLB A+ patients compared with DLB A− patients. Plasma GFAP and NfL concentrations did not differ between A− and A+ patients with DLB. Plasma biomarkers were compared between groups by ANCOVA corrected for age and sex. *p < 0.05. Aβ = β-amyloid; AD = Alzheimer disease; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; HC = healthy control; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NfL = neurofilament light; P-tau = phosphorylated tau.

Association of Plasma Biomarkers With Cognitive Impairment and Decline

In the DLB group, GFAP, NfL, P-tau181, and P-tau231, but not Aβ42/40 ratio, were associated with global cognitive impairment (MMSE) at baseline (Aβ42/40: β = −13.18, 95% CI −56.42 to 30.05, p = 0.549; GFAP: β = −9.25, 95% CI −12.06 to −6.44, p < 0.001; NfL: β = −7.41, 95% CI −10.28 to −4.54, p < 0.001; P-tau: β = −2.61, 95% CI −3.99 to −1.24, p < 0.001; P-tau: β = −2.42, 95% CI −3.67 to −1.17, p < 0.001) when corrected for age and sex. On additional correction for years of education, this effect remained significant for GFAP (β = −4.11, 95% CI −8.06 to −0.16, p = 0.04) and P-tau181 (β = −1.75, 95% CI −3.49 to −0.01, p < 0.05), but lost significance for NfL (β = −2.58, 95% CI −6.30 to −1.14, p = 0.17) and P-tau231 (β = −1.48, 95% CI −3.19 to 0.23, p = 0.09). Similar associations were found in the AD group, but no association with cognition at baseline was found in HC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of Baseline Plasma Biomarkers With Global Cognition at Baseline After Correction for Age and Sex

| HC | DLB | AD | ||||

| Estimate (95% CI) | p Value | Estimate (95% CI) | p Value | Estimate (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Aβ42/40 | −9.64 (−41.59 to 22.31) | 0.549 | −13.18 (−56.42 to 30.05) | 0.549 | −1.64 (−88.87 to 85.59) | 0.970 |

| GFAPa | 0.93 (−1.37 to 3.23) | 0.424 | −9.25 (−12.06 to −6.44) | <0.001 | −11.54 (−16.20 to −6.87) | <0.001 |

| NfLa | 0.55 (−1.58 to 2.68) | 0.610 | −7.41 (−10.28 to −4.54) | <0.001 | −10.88 (−15.92 to −5.84) | <0.001 |

| P-tau181a | 0.56 (−0.86 to 1.98) | 0.437 | −2.61 (−3.99 to −1.24) | <0.001 | −4.25 (−6.79 to −1.70) | <0.01 |

| P-tau231a | −0.05 (−1.14 to 1.04) | 0.922 | −2.42 (−3.67 to −1.17) | <0.001 | −4.92 (−7.08 to −2.76) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: Aβ = β-amyloid; AD = Alzheimer disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; HC = healthy control; NfL = neurofilament light; P-tau = phosphorylated tau.

Biomarker concentrations were log-transformed.

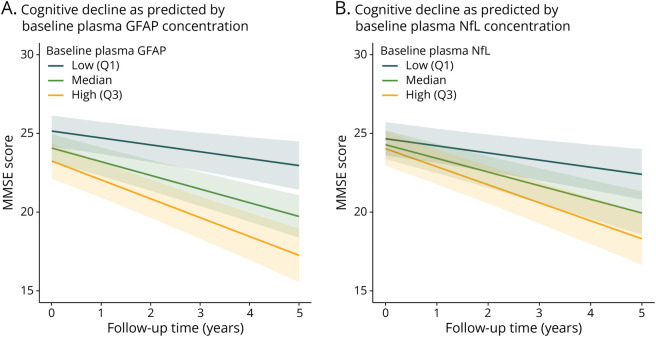

Longitudinal MMSE data were available for 156 DLB individuals with follow-up times of up to 5 years (5 years: n = 44, 4 years: n = 24, 3 years: n = 24, 2 years: n = 35, 1 year: n = 29), with a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.1 (1.5) years. Years of education were not associated with the rate of cognitive decline (β = −0.03, 95% CI −0.14 to 0.08, p = 0.57; eFigure 2). Although Aβ42/40 was not associated with cognitive decline in the DLB group, GFAP concentration was associated with an annual change of −2.11 MMSE points (95% CI −2.88 to −1.35 MMSE points, p < 0.001) and NfL concentration was associated with an annual change of −2.13 MMSE points (95% CI −2.97 to −1.29 MMSE points, p < 0.001) (Figure 4) after correction for age and sex. After additional correction for years of education, these associations lost significance (GFAP: β = −0.40, 95% CI −3.12 to 2.34, p = 0.78; NfL: β = −1.92, 95% CI −4.14 to 0.38, p = 0.10) and the addition of NfL to the GFAP model did not improve the model performance (AIC 3,116.4 vs 3,116.1).

Figure 4. Associations of Baseline Plasma GFAP and NfL With Cognitive Decline in Patients With Dementia With Lewy Bodies.

Association of cognitive decline with baseline plasma GFAP (A) and NfL (B) concentrations. Linear mixed-effects models, corrected for the effect of age and sex, were built to analyze the association of baseline plasma biomarker concentrations with cognitive decline, as measured by MMSE scores over time, for up to 5 years. The line represents the estimated marginal model of decrease in MMSE scores over up to 5 years of follow-up time with different baseline plasma biomarker concentrations. To illustrate the association of different baseline biomarker concentrations with rate of cognitive decline, low and high biomarker concentrations were defined as the first (Q1) and third quartile (Q3), respectively. The transparent areas show 95% CIs around the mean estimated values. AD = Alzheimer disease; GFAP = glial fibrillary acidic protein; HC = healthy control; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; NfL = neurofilament light.

Association of Plasma Biomarkers With DLB Core Features and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT Status

DLB core features are summarized in Table 1. None of the biomarkers were associated with the presence of visual hallucinations or RBD in the DLB group. Higher concentration of NfL was associated with the presence of parkinsonism (β = 0.08, 95% CI 0.02–0.14, p = 0.006), and lower P-tau231 was associated with fluctuations of cognition (β = −0.18, 95% CI −0.33 to −0.02, p < 0.05; eFigure 3). These associations were not significant for any of the other plasma biomarkers. Levels of plasma biomarkers did not differ between 123I-FP-CIT SPECT status normal and abnormal individuals (eFigure 4). Graphs showing each plasma biomarker in association with DLB core features and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT status are presented in eFigure 3.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the association of plasma Aβ42/40, GFAP, and NfL with amyloid copathology, progression of cognition, and clinical core features of DLB in a large E-DLB multicenter cohort. We found that the plasma Aβ42/40 ratio was higher in patients with DLB compared with AD and not significantly different from HC, while plasma GFAP and NfL were higher in patients with DLB and AD compared with HC, but not significantly different between DLB and AD, and P-tau181 and P-tau231 were significantly higher in DLB compared with HC and significantly lower in DLB and HC compared with AD. In DLB, higher GFAP and NfL at baseline were associated with cognitive impairment and predicted faster cognitive decline. Only the Aβ42/40 ratio and both P-tau species were associated with CSF Aβ42 status in DLB. Increased plasma NfL concentrations were associated with the presence of parkinsonism, and increased P-tau231 concentrations were present in the absence of fluctuations of cognition.

NfL is released into body fluids on axonal damage, indicating neurodegenerative processes.31 GFAP is known to be a marker for astrocyte activation, a pathologic process involved in various neurologic diseases and specifically associated with amyloid pathology in AD.32 Increased concentrations of blood NfL and GFAP have previously been shown in both AD33-35 and DLB (total study group n = 300, of which n = 110 DLB).16 The increase of plasma GFAP in DLB, without being associated with amyloid copathology in the DLB group, could indicate that GFAP may also reflect different processes in DLB compared with AD, such as neurodegeneration and/or α-syn pathology.

The increase in plasma NfL and GFAP concentrations was associated with cognitive impairment and a more rapid cognitive decline in the DLB group, with a stronger association for GFAP. In AD, this relationship has been shown before.34,36 On correction for years of education, this association lost significance, which is most likely due to a loss of power caused by missing data (n = 98 (62.8%) of n = 156). As described by the cognitive reserve theory, higher educational levels are believed to extend the time to cognitive decline.37 However, it has been proposed before that the rate of neurodegenerative processes is not influenced by educational levels.38 Instead, it is possible that although patients of higher education would have higher baseline MMSE levels, the rate of cognitive decline would still be comparable with that of patients with lower education and similar baseline plasma NfL or GFAP concentrations. In our data, we could observe that indeed the rate of cognitive decline was not altered on stratification for educational levels (eFigure 2). These findings could indicate that NfL and particularly GFAP as markers for neurodegeneration and astrogliosis, respectively, could have a value for monitoring cognition in DLB. Although higher levels of both P-tau species were associated with worse cognitive impairment at baseline, associations with cognitive decline did not reach significance, unlike in a previous report.17 This loss of significance is likely explained by the inclusion of only a subgroup of the initial E-DLB cohort in this study.

As expected, the plasma Aβ42/40 ratio was decreased, and both P-tau species were increased in amyloid positive DLB individuals, as defined by CSF Aβ42, indicating plasma Aβ42/40 ratio, P-tau181, and P-tau231 to be suitable, less invasive markers to assess amyloid copathology. This association was not observed for plasma GFAP. Already in early stages of AD, a close relationship between GFAP concentration and amyloid burden, as determined by Aβ PET or CSF Aβ42/40 ratio, has been shown in several studies.33,35,39 In DLB, however, inconsistent findings concerning the association of GFAP with Aβ PET have been reported.16,40 As previously suggested, other pathologic processes, such as α-syn deposition causing neuroinflammation,8 could affect astrogliosis,41-44 possibly masking the association of GFAP concentration with amyloid burden in DLB.

These findings suggest the utility of plasma Aβ42/40, P-tau181, and P-tau231 to assess amyloid abnormality, and NfL and GFAP to monitor disease progression in DLB. Although the general trend of biomarker levels across groups is coherent with previous studies,14-16 we still observed large heterogeneity of biomarker concentrations within, and substantial overlap of biomarker concentrations between groups, which diminishes their utility for differential diagnosis of DLB.

We show that patients with DLB with parkinsonism present with higher plasma NfL concentration than those without parkinsonism. These results corroborate previous results of increased plasma NfL concentration in atypical parkinsonism disorders45 and predicting faster motor progression in PD,46 possibly caused by more pronounced neurodegeneration. The lack of such associations with other core features, such as recurrent visual hallucinations and RBD, could suggest that these features may have a stronger functional component.47-49

Strengths of this study include the large sample size, the longitudinal data for a subgroup, and multicenter design. Our study also faced some limitations. Owing to the retrospective and naturalistic character of our study, some variables included missing data, only allowing for certain analyses in subsets of the cohort, for example, CSF amyloid measurements were based on Aβ42 alone and available in 45 patients with AD and 101 patients with DLB. Of the included patients with DLB with available 123I-FP-CIT SPECT scan information, 21.0% (n = 22) were rated as normal. It has been shown that normal 123I-FP-CIT SPECT scans are found in around 10% of patients with DLB and can convert to abnormal over time.50 Furthermore, individuals with normal 123I-FP-CIT SPECT did not show significantly different biomarker concentrations compared with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT abnormal patients with DLB (data not shown), but the possible inclusion of misdiagnosed cases cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, we evaluated association of biomarkers with cognitive decline based on MMSE. This measure is rather domain-unspecific and more specific assessments could give more detailed insights into disease progression. In addition, although all statistical analyses were corrected for the confounding effect of age, it is important to emphasize that this might not fully eliminate the effect of the control group being of significant younger age compared with both disease groups.

Our findings suggest the possible utility of plasma GFAP and NfL for monitoring disease progression in patients with DLB in the future, which would make them relevant outcomes in clinical trials. Further longitudinal studies and analyzing the association with other disease progression measures such as survival rate will be needed to verify our findings. Adding to the previous findings for P-tau181 and P-tau231,17 we found an association of plasma Aβ42/40 ratio and amyloid copathology in DLB, indicating a possible utility of these markers to assess amyloid copathology in DLB as a less invasive alternative to CSF. These markers could become beneficial for patient selection and stratification in clinical trials, patient selection for anti-amyloid treatment, and could aid in understanding the influence of amyloid copathology on disease progression and survival in DLB. However, validation of our findings in amyloid PET abnormal DLB participants would be valuable, further correlation studies in DLB are needed, and cutoff values need to be established.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Hans Heijst, Zulaiga Q. Hussainali, and Daimy N. Ruiters for their kind help in performing the Simoa N4PE measurements.

Glossary

- 123I-FP-CIT

123I-N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane

- α-syn

α-synuclein

- A+

amyloid abnormal

- A−

amyloid normal

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- E-DLB

European-Dementia With Lewy Bodies

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- HC

healthy control

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- NfL

neurofilament light

- PD

Parkinson disease

- P-tau

phosphorylated-tau

- RBD

REM sleep behavior disorder

Appendix 1. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Katharina Bolsewig, MSc | Department of Laboratory Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Annemartijn A.J.M. van Unnik, MD | Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Elena R. Blujdea, MSc | Department of Laboratory Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Maria C. Gonzalez, MD | Department of Quality and Health Technology, University of Stavanger; The Norwegian Centre for Movement Disorders, Stavanger University Hospital; Centre for Age-Related Medicine, Stavanger University Hospital, Norway | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; additional contributions: administrative, technical, or material support |

| Nicholas J. Ashton | Centre for Age-Related Medicine, Stavanger University Hospital, Norway; Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden; Department of Old Age Psychiatry, King's College London, UK | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; additional contributions: administrative, technical, or material support |

| Dag Aarsland, MD, PhD | Centre for Age-Related Medicine, Stavanger University Hospital, Norway; Department of Old Age Psychiatry, King's College London, UK | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; additional contributions: administrative, technical, or material support |

| Henrik Zetterberg, MD, PhD | Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg; Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden; Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Institute of Neurology, London; UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL, London; Hong Kong Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, China; Wisconsin Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Alessandro Padovani, MD, PhD | Neurology Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Italy | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Laura Bonanni, MD, PhD | Department of Medicine and Aging Sciences, University G. d'Annunzio of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Brit Mollenhauer | Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Göttingen; Paracelsus-Elena-Klinik Kassel, Kassel, Germany | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Sebastian Schade, MD | Paracelsus-Elena-Klinik, Kassel Germany | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Rik Vandenberghe, MD, PhD | Department of Neurosciences, KU Leuven, Belgium | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Koen Poesen, MD, PhD | Department of Neurosciences, KU Leuven, Belgium | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Milica G. Kramberger, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology and Medical Faculty, University Medical Center Ljubljana, Slovenia; Department of Neurobiology, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Claire Paquet | Université de Paris Cité, Centre de Neurologie Cognitive, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Olivier Bousiges, PharmD, PhD | Laboratory of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, Strasbourg, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Benjamin Cretin | University of Strasbourg and CNRS; Memory Resource and Research Centre, University Hospital of Strasbourg, France | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Eline A.J. Willemse | Department of Laboratory Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands; Department of Neurology, Multiple Sclerosis Center and Research Center for Clinical Neuroimmunology and Neuroscience Basel; Departments of Biomedicine and Clinical Research, University Hospital Basel and University of Basel, Switzerland | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; additional contributions: supervision |

| Charlotte E. Teunissen, PhD | Department of Laboratory Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; additional contributions: obtained funding; supervision |

| Afina W. Lemstra | Alzheimer Center Amsterdam, Amsterdam UMC, the Netherlands | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; additional contributions: administrative, technical, or material support; supervision |

Appendix 2. Coinvestigators

| Name | Location | Role | Contribution |

| Claudia Carrarini, MD | Department of Neuroscience, Imaging, and Clinical Sciences, G. d'Annunzio University of Chieti-Pescara, Italy | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Julien Dumurgier, MD, PhD | Centre de Neurologie Cognitive, GHU APHP Nord Hôpital Lariboisière Fernand-Widal, Paris, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Claire, Hourregue, MD | Centre de Neurologie Cognitive, GHU APHP Nord Hôpital Lariboisière Fernand-Widal, Paris, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Sinead Gaubert, MD | Centre de Neurologie Cognitive, GHU APHP Nord Hôpital Lariboisière Fernand-Widal, Paris, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Maximilien Porché, MD | Centre de Neurologie Cognitive, GHU APHP Nord Hôpital Lariboisière Fernand-Widal, Paris, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Matthieu Lilamand, MD, PhD | Centre de Neurologie Cognitive, GHU APHP Nord Hôpital Lariboisière Fernand-Widal, Paris, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Frédéric Blanc, MD, PhD | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, ICube Laboratory UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), IMIS team, France | Principal investigator | Data collection |

| Pierre Anthony, MD | CM2R, Neuropsychology Unit, Head and Neck Department, Neurology Department, University of Strasbourg; CM2R, Geriatric Day Hospital, Geriatrics Division, Civil Hospitals of Colmar, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Catherine Demuynck, MD | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, ICube Laboratory UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), IMIS team, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Catherine Martin-Hunyadi, MD | Centre Mémoire, de Ressources et de Recherche d'Alsace, Strasbourg-Colmar, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Candice Muller, MD | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, ICube Laboratory UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), IMIS team, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Nathalie Philippi, MD | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, ICube Laboratory UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), IMIS team, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Alix Ravier, MD | CM2R (Memory Resource and Research Centre), Geriatrics Department, University Hospitals of Strasbourg, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Anne Botzung, PhD | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, ICube Laboratory UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), IMIS team, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Timothée Albasser | CM2R (Memory Resource and Research Centre), Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; 2 CNRS, ICube Laboratory, UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), Team IMIS, University of Strasbourg, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Emmanuelle Epp-Ehrhardt | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Jeanne Merignac | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg; University of Strasbourg and CNRS, ICube Laboratory UMR 7357 and FMTS (Fédération de Médecine Translationnelle de Strasbourg), IMIS team, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Laetitia Monjoin | Memory Resource and Research Centre, Geriatrics Day Hospital, Geriatrics Department, University Hospital of Strasbourg, France | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Isabelle Cleynen, PhD | Laboratory for Complex Genetics, Department of Human Genetics, KU Leuven, Belgium | Site investigator | Data collection |

| Mercè Boada, MD, PhD | Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona, Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya-Barcelona, Centro de Investigación en Red-Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Spain | Principal investigator | Data collection |

| Adela Orellana, PhD | Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona, Institut Català de Neurociències Aplicades, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya-Barcelona, Centro de Investigación en Red-Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Spain | Site investigator | Data collection |

Footnotes

Editorial, page e209505

Study Funding

K. Bolsewig, H. Zetterberg, E.A.J. Willemse, and C.E. Teunissen are supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 860197 (MIRIADE). H. Zetterberg is a Wallenberg Scholar supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (#2022-01018), the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101053962, Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (#ALFGBG-71320), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF), United States (#201809-2016862), the AD Strategic Fund and the Alzheimer's Association (#ADSF-21-831376-C, #ADSF-21-831381-C, and #ADSF-21-831377-C), the Bluefield Project, the Olav Thon Foundation, the Erling-Persson Family Foundation, Stiftelsen för Gamla Tjänarinnor, Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2022-0270), the European Union Joint Programme—Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND2021-00694), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL (UKDRI-1003). Research of C.E. Teunissen is supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiatives 3TR (Horizon 2020, grant no 831434) EPND (IMI 2 Joint Undertaking (JU), grant no. 101034344) and JPND (bPRIDE), National MS Society (Progressive MS alliance), Alzheimer Association, Health Holland, the Dutch Research Council (ZonMW), Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, The Selfridges Group Foundation, Alzheimer, the Netherlands. C.E. Teunissen is recipient of ABOARD, which is a public-private partnership receiving funding from ZonMW (#73305095007) and Health∼Holland, Topsector Life Sciences & Health (PPP-allowance; #LSHM20106). C.E. Teunissen is recipient of TAP-dementia, a ZonMw funded project (#10510032120003) in the context of the Dutch National Dementia Strategy.

Disclosure

K. Bolsewig, A.A.J.M. van Unnik, E.R. Blujdea, M.C. Gonzales, and N.J. Ashton report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. D. Aarsland reports receiving research support and/or honoraria from AstraZeneca, H. Lundbeck, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Biogen, Evonik, Sanofi, Roche, and GE Health and serving as a paid consultant for H. Lundbeck, Eisai, Heptares, and Mentis Cura. H. Zetterberg has served at scientific advisory boards and/or as a consultant for Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alzinova, ALZPath, Annexon, Apellis, Artery Therapeutics, AZTherapies, CogRx, Denali, Eisai, Nervgen, Novo Nordisk, Optoceutics, Passage Bio, Pinteon Therapeutics, Prothena, Red Abbey Labs, reMYND, Roche, Samumed, Siemens Healthineers, Triplet Therapeutics, and Wave, has given lectures in symposia sponsored by Cellectricon, Fujirebio, Alzecure, Biogen, and Roche, and is a co-founder of Brain Biomarker Solutions in Gothenburg AB (BBS), which is a part of the GU Ventures Incubator Program (outside submitted work). A. Padovani reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. L. Bonanni reported receiving grants from the European Commission and the Italian Ministry of Health outside the submitted work. B. Mollenhauer reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Schade received institutional salaries supported by the EU Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 863664 and by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research under grant agreement no. MJFF-021923. He is supported by a PPMI Early Stage Investigators Funding Program fellowship of the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research under grant agreement no. MJFF-022656. R. Vandernberghe's institution has a clinical trial agreement (R. Vandenberghe as PI) with AviadoBio, Biogen, Denali, J&J, NovoNordisk, Prevail, Roche, UCB, Wave. R. Vandenberghe's institution has a consultancy agreement (R. Vandenberghe as a consultant) with ACImmune, Novartis, and Roche. K. Poesen and M.G. Kramberger report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. C. Paquet reports serving as a member of the international advisory boards for Lilly; serving as a consultant for Fujiribio, Alzohis, Neuroimmune, Ads Neuroscience, Roche, AgenT, and Gilead; being involved as an investigator in several clinical trials for Roche, Eisai, Lilly, Biogen, AstraZeneca, Lundbeck, and Neuroimmune; and being a current member of the national boards of Roche, Lilly, and Biogen. O. Bousiges, B. Cretin, and E.A.J. Willemse report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. C.E. Teunissen has a collaboration contract with ADx Neurosciences, Quanterix, and Eli Lilly, performed contract research or received grants from AC-Immune, Axon Neurosciences, BioConnect, Bioorchestra, Brainstorm Therapeutics, Celgene, EIP Pharma, Eisai, Fujirebio, Grifols, Instant Nano Biosensors, Merck, Novo Nordisk, PeopleBio, Roche, Siemens, Toyama, and Vivoryon. She is an editor of Alzheimer Research and Therapy, and serves on editorial boards of Medidact Neurologie/Springer, and Neurology: Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation. She had speaker contracts for Roche, Grifols, Novo Nordisk. A.W. Lemstra reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D. Lewy body dementias. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1683-1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00462-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88-100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giil LM, Aarsland D. Greater variability in cognitive decline in Lewy body dementia compared to Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;73(4):1321-1330. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemstra AW, de Beer MH, Teunissen CE, et al. Concomitant AD pathology affects clinical manifestation and survival in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(2):113-118. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller C, Soysal P, Rongve A, et al. Survival time and differences between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease following diagnosis: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;50:72-80. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price A, Farooq R, Yuan JM, Menon VB, Cardinal RN, O'Brien JT. Mortality in dementia with Lewy bodies compared with Alzheimer's dementia: a retrospective naturalistic cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017504. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irwin DJ, Hurtig HI. The contribution of tau, amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein pathology to dementia in Lewy body disorders. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism. 2018;8(4):444. doi: 10.4172/2161-0460.1000444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amin J, Erskine D, Donaghy PC, et al. Inflammation in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiol Dis. 2022;168:105698. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2022.105698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson DH, Rissin DM, Kan CW, et al. The Simoa HD-1 analyzer: a novel fully automated digital immunoassay analyzer with single-molecule sensitivity and multiplexing. J Lab Autom. 2016;21(4):533-547. doi: 10.1177/2211068215589580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hampel H, Hu Y, Cummings J, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: current state and future use in a transformed global healthcare landscape. Neuron. 2023;111(18):2781-2799. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, et al. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(9):1035-1048. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilotto A, Imarisio A, Carrarini C, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain predicts cognitive progression in prodromal and clinical dementia with Lewy bodies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82(3):913-919. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishiki A, Kamada M, Kawamura Y, et al. Glial fibrillar acidic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurochem. 2016;136(2):258-261. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thijssen EH, Verberk IMW, Kindermans J, et al. Differential diagnostic performance of a panel of plasma biomarkers for different types of dementia. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2022;14(1):e12285. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baiardi S, Quadalti C, Mammana A, et al. Diagnostic value of plasma p-tau181, NfL, and GFAP in a clinical setting cohort of prevalent neurodegenerative dementias. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01093-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chouliaras L, Thomas A, Malpetti M, et al. Differential levels of plasma biomarkers of neurodegeneration in Lewy body dementia, Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia and progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(6):651-658. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-327788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez MC, Ashton NJ, Gomes BF, et al. Association of Plasma p-tau181 and p-tau231 concentrations with cognitive decline in patients with probable dementia with Lewy bodies. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(1):32-37. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mila-Aloma M, Ashton NJ, Shekari M, et al. Plasma p-tau231 and p-tau217 as state markers of amyloid-β pathology in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2022;28(9):1797-1801. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01925-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janelidze S, Bali D, Ashton NJ, et al. Head-to-head comparison of 10 plasma phospho-tau assays in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2023;146(4):1592-1601. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oppedal K, Borda MG, Ferreira D, Westman E, Aarsland D; European DLB Consortium. European DLB consortium: diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in dementia with Lewy bodies, a multicenter international initiative. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2019;9(5):247-250. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2019-0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferman TJ, Smith GE, Boeve BF, et al. DLB fluctuations: specific features that reliably differentiate DLB from AD and normal aging. Neurology. 2004;62(2):181-187. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308-2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahn S, Elton RL; Members of the UPDRS Development Committee. The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, Goldstein M, eds. Recent Developments in Parkinson's Disease. McMellam Health Care Information; 1987:153-163. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boeve BF, Molano JR, Ferman TJ, et al. Validation of the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire to screen for REM sleep behavior disorder in an aging and dementia cohort. Sleep Med. 2011;12(5):445-453. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [computer program]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.pastecs: Package for Analysis of Space-Time Ecological Series [computer program]. R package version 1.4.2. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P. Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometric J. 2008;50(3):346-363. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw. 2017;82(13):1-26. doi: 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, Di Filippo M, Parnetti L, Zetterberg H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(8):870-881. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colangelo AM, Alberghina L, Papa M. Astrogliosis as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosci Lett. 2014;565:59-64. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira JB, Janelidze S, Smith R, et al. Plasma GFAP is an early marker of amyloid-β but not tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2021;144(11):3505-3516. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(5):557-566. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.6117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benedet AL, Mila-Aloma M, Vrillon A, et al. Differences between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid glial fibrillary acidic protein levels across the Alzheimer Disease Continuum. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(12):1471-1483. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajan KB, Aggarwal NT, McAninch EA, et al. Remote blood biomarkers of longitudinal cognitive outcomes in a population study. Ann Neurol. 2020;88(6):1065-1076. doi: 10.1002/ana.25874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stern Y. What is cognitive reserve? Theory and research application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(3):448-460. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702813248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krivanek TJ, Gale SA, McFeeley BM, Nicastri CM, Daffner KR. Promoting successful cognitive aging: a ten-year update. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;81(3):871-920. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cicognola C, Janelidze S, Hertze J, et al. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein detects Alzheimer pathology and predicts future conversion to Alzheimer dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00804-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donaghy PC, Firbank M, Petrides G, et al. The relationship between plasma biomarkers and amyloid PET in dementia with Lewy bodies. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;101:111-116. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2022.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chavarria C, Rodriguez-Bottero S, Quijano C, Cassina P, Souza JM. Impact of monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar alpha-synuclein on astrocyte reactivity and toxicity to neurons. Biochem J. 2018;475(19):3153-3169. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20180297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koob AO, Paulino AD, Masliah E. GFAP reactivity, apolipoprotein E redistribution and cholesterol reduction in human astrocytes treated with alpha-synuclein. Neurosci Lett. 2010;469(1):11-14. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Togo T, Iseki E, Marui W, Akiyama H, Ueda K, Kosaka K. Glial involvement in the degeneration process of Lewy body-bearing neurons and the degradation process of Lewy bodies in brains of dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Sci. 2001;184(1):71-75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00498-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HJ, Suk JE, Patrick C, et al. Direct transfer of alpha-synuclein from neuron to astroglia causes inflammatory responses in synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(12):9262-9272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marques TM, van Rumund A, Oeckl P, et al. Serum NFL discriminates Parkinson disease from atypical parkinsonisms. Neurology. 2019;92(13):e1479-e1486. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilotto A, Imarisio A, Conforti F, et al. Plasma NfL, clinical subtypes and motor progression in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021;87:41-47. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Satoh M, Ishikawa H, Meguro K, Kasuya M, Ishii H, Yamaguchi S. Improved visual hallucination by donepezil and occipital glucose metabolism in dementia with Lewy bodies: the Osaki-Tajiri project. Eur Neurol. 2010;64(6):337-344. doi: 10.1159/000322121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkelman JW, James L. Serotonergic antidepressants are associated with REM sleep without atonia. Sleep. 2004;27(2):317-321. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matar E, Ehgoetz Martens KA, Phillips JR, et al. Dynamic network impairments underlie cognitive fluctuations in Lewy body dementia. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8(1):16. doi: 10.1038/s41531-022-00279-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Zande JJ, Booij J, Scheltens P, Raijmakers PG, Lemstra AW. [(123)]FP-CIT SPECT scans initially rated as normal became abnormal over time in patients with probable dementia with Lewy bodies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(6):1060-1066. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3312-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data access to anonymized patient-level data can be requested from the corresponding author on reasonable request.