Abstract

Background and Objectives

Executive functioning is one of the first domains to be impaired in Parkinson disease (PD), and the majority of patients with PD eventually develop dementia. Thus, developing a cognitive endpoint measure specifically assessing executive functioning is critical for PD clinical trials. The objective of this study was to develop a cognitive composite measure that is sensitive to decline in executive functioning for use in PD clinical trials.

Methods

We used cross-sectional and longitudinal follow-up data from PD participants enrolled in the PD Cognitive Genetics Consortium, a multicenter setting focused on PD. All PD participants with Trail Making Test, Digit Symbol, Letter-Number Sequencing, Semantic Fluency, and Phonemic Fluency neuropsychological data collected from March 2010 to February 2020 were included. Baseline executive functioning data were used to create the Parkinson's Disease Composite of Executive Functioning (PaCEF) through confirmatory factor analysis. We examined the changes in the PaCEF over time, how well baseline PaCEF predicts time to cognitive progression, and the required sample size estimates for PD clinical trials. PaCEF results were compared with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), individual tests forming the PaCEF, and tests of visuospatial, language, and memory functioning.

Results

A total of 841 participants (251 no cognitive impairment [NCI], 480 mild cognitive impairment [MCI], and 110 dementia) with baseline data were included, of which the mean (SD) age was 67.1 (8.9) years and 270 were women (32%). Five hundred forty five PD participants had longitudinal neuropsychological data spanning 9 years (mean [SD] 4.5 [2.2] years) and were included in analyses examining cognitive decline. A 1-factor model of executive functioning with excellent fit (comparative fit index = 0.993, Tucker-Lewis index = 0.989, and root mean square error of approximation = 0.044) was used to calculate the PaCEF. The average annual change in PaCEF ranged from 0.246 points per year for PD-NCI participants who remained cognitively unimpaired to −0.821 points per year for PD-MCI participants who progressed to dementia. For PD-MCI, baseline PaCEF, but not baseline MoCA, significantly predicted time to dementia. Sample size estimates were 69%–73% smaller for PD-NCI trials and 16%–19% smaller for PD-MCI trials when using the PaCEF rather than MoCA as the endpoint.

Discussion

The PaCEF is a sensitive measure of executive functioning decline in PD and will be especially beneficial for PD clinical trials.

Introduction

Although motor symptoms have traditionally defined Parkinson disease (PD), cognitive impairment significantly affects quality of life and function in PD1 and dementia occurs in over 80% of patients who have had PD for more than 20 years.2 Because of this, a significant number of clinical trials are specifically targeting cognitive impairment in PD.3 However, the most common cognitive outcome measures used in these trials are not specifically created for or tested in PD. Instead, most cognition-focused PD clinical trials use screening measures with poor sensitivity,4 test batteries that were not specifically designed for older adults5 even though PD occurs primarily in older age, or measures designed for Alzheimer disease, which has a different cognitive profile and course.6 Thus, a major challenge for PD clinical trials targeting cognition is the lack of an optimal outcome measure that is sensitive to cognitive decline in PD.

A recent review of clinical trials performed between 2016 and 2021 that targeted cognition in PD indicated an overall lack of intervention effectiveness beyond 4 months.3 This review also raised the issue of suboptimal cognitive outcome measures in PD clinical trials and highlighted that most trials used the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) as the outcome. Similarly, a PD Endpoints Roundtable that examined outcomes used in 142 registered clinical trials in early PD also emphasized the heterogeneity in clinical trial outcome measures and identified the MoCA as the only cognitive measure used by more than 2 current trials.7 However, the MoCA and the closely related Mini-Mental State Examination are global screening measures that have poor sensitivity for detecting decline over 1 year in non-demented PD individuals.4,8 The other cognitive outcomes used in phase 2/3 trials between 2016 and 2021 with results described in peer-reviewed or preprint articles were the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale—Cognitive Subscale (ADASCog),9 Sustained Attention Test (SAT),10 and Verbal Fluency.11 The ADASCog does not assess executive functioning, attention, or non-motor visuospatial ability,12 3 core domains that may be affected in PD,13,14 and was not specifically designed or recommended for PD. Both the SAT and Verbal Fluency are individual cognitive measures that are often only 1 test included in a more comprehensive neuropsychological test battery. Indeed, for the trial that used the SAT as the cognitive outcome, it is notable that several other cognitive tests were administered and examined, but only the SAT was listed as an outcome measure.10

Composite scores (e.g., NIH-EXAMINER Executive Functioning composite) leverage all cognitive data, but are currently used by relatively few trials.15-17 In addition, longitudinal changes in performance on these composites have not been studied in PD, especially in larger patient samples. More comprehensive screening measures assess multiple domains, but also have limited utility as a cognitive outcome measure for clinical trials. For example, the Dementia Rating Scale—Second Edition has been recommended for use in PD,18 but is subject to ceiling effects and its subscales have limited construct validity.19 A subset of tests from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery, a computerized battery, has been recommended for PD by the developers, but its psychometric properties and ability to detect change have not yet been examined in PD. The PD-Cognitive Rating Scale is able to cross-sectionally distinguish PD with no cognitive impairment (PD-NCI), PD with mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI), and PD dementia (PDD)20 and has shown sensitivity to change,21 but the optimal cutpoint for identifying PD-MCI has been debated.22 The Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson's Disease—Cognition is a 10-item assessment covering memory, attention, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability that can identify cognitive impairment in PD, but, like the MoCA, its ability to detect decline in non-demented PD is poor.4 Together, these limitations highlight the need for the development of a cognitive outcome measure with demonstrated sensitivity to change in cognition specifically in PD.

Although memory impairment is commonly reported in PD,14 deficits in executive functioning, attention, and visuospatial abilities are more closely related to dopaminergic functioning23 and Lewy body pathology,24 the hallmarks of PD. In a study that asked patients with PD to identify up to 3 symptoms of PD that they would like to see improvement in, cognitive function was identified as the seventh most common symptom in those diagnosed for 2 years or less and the descriptions of the cognitive symptoms were primarily executive dysfunction (e.g., clarity of thought and ability to concentrate and multi-task).25 In addition, executive dysfunction has been shown to predict conversion to PDD26 and many clinical trial therapeutics are specifically targeting the fronto-striatal circuit responsible for executive functioning. Thus, the goals of the present study were to (1) create the Parkinson's Disease Composite of Executive-Functioning (PaCEF), (2) examine PaCEF score changes over time, (3) determine whether the PaCEF can predict time to progression in patients with PD, and (4) estimate the required sample sizes for future clinical trials using the PaCEF to detect cognitive decline. Results are compared with the MoCA, individual tests forming the PaCEF, and tests of visuospatial, language, and memory functioning.

Methods

This study leveraged neuropsychological data from Pacific Udall Center Clinical Consortium,27 a subset of research centers that share data within the Parkinson's Disease Cognitive Genetics Consortium (PDCGC)28 that agreed a priori to collect a core set of cognitive and clinical measures and participate in clinical, motor, and cognitive consensus diagnosis conferences attended by the same study movement disorders specialist and neuropsychologist along with site-specific study personnel. Data for this study included the 4 sites with available longitudinal data (University of Washington/VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Oregon Health & Sciences University/VA Portland, Stanford University, and Johns Hopkins University). Cognitive testing at these sites was conducted in the ON dopaminergic medication state, as recommended,29 and included a comprehensive neuropsychological battery (eTable 1). All included participants met UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank Diagnostic (UKBB) criteria for Parkinson disease30; had available cognitive diagnostic data; and had complete baseline data for all executive functioning tests (Table 1); participants with missing baseline data were excluded (eTable 2; eResults).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the (A) Cross-Sectional and (B) Longitudinal Samples

| A. Cross-sectional sample | PD-NCI (n = 251) | PD-MCI (n = 480) | PDD (n = 110) | p Valuea |

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 64.7 (8.4) | 67.7 (8.7) | 70.3 (9.4) | <0.0001c PD-NCI < PD-MCI < PDD |

| Range | 40.3–84.8 | 36.2–91.3 | 35.1–89.2 | |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 121 (48.2) | 353 (73.5) | 97 (88.2) | <0.0001c PD-NCI < PD-MCI < PDD |

| Education, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.4 (2.4) | 16.0 (2.5) | 15.5 (2.8) | 0.006c PD-NCI > PDD |

| Range | 12–20 | 4–20 | 8–20 | |

| Disease duration, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.4 (4.9) | 8.1 (5.9) | 10.5 (6.8) | <0.0001c PD-NCI | PD-MCI < PDD |

| Range | 0.3–30.4 | 0.3–40.9 | 0.2–33.0 | |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.672 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 (1.6) | 5 (1.0) | 2 (1.8) | |

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (1.8) | |

| More than 1 race | 3 (1.2) | 8 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) | |

| White | 243 (96.8) | 457 (95.2) | 105 (95.5) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 4 (1.6) | 6 (1.3) | 2 (1.8) | 0.810 |

| Non-Hispanic | 242 (96.4) | 469 (97.7) | 107 (97.3) | |

| Unknown | 5 (2.0) | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| MDS-UPDRS Part III score (n = 822) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.7 (10.6) | 26.7 (11.5) | 35.1 (13.2) | <0.0001c PD-NCI < PD-MCI < PDD |

| Range | 3.0–64.0 | 4.0–66.0 | 11–68 | |

| Modified Hoehn & Yahr (n = 840) | ||||

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2.5 | <0.001c PD-NCI < PD-MCI < PDD |

| Range | 1–4 | 1–5 | 1–5 | |

| LEDD, mg/d (n = 830) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 544.3 (460.7) | 605.0 (483.5) | 699.4 (560.0) | 0.021c PD-NCI < PDD |

| Range | 0–2886.9 | 0–3750.0 | 0–3364.0 | |

| GBA (n = 834), n (%) | 23 (9.2) | 43 (9.0) | 28 (25.9) | <0.001c PD-NCI | PD-MCI < PDD |

| APOE ε4+ (n = 825), n (%) | 52 (20.9) | 112 (23.8) | 25 (23.6) | 0.660 |

| MoCA, total score (n = 836) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 26.5 (2.0) | 23.9 (2.5) | 19.6 (3.5) | <0.0001c PD-NCI > PD-MCI > PDD |

| Range | 21–30 | 16–29 | 8–28 |

| B. Longitudinal sample | PD-NCI at baseline | PD-MCI at baseline | ||||

| Stable (n = 110) | Progressed to PD-MCI/PDD (n = 68) | p Valueb | Stable (n = 260) | Progressed to PDD (n = 107) | p Valueb | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 63.5 (8.8) | 64.9 (7.4) | 0.280 | 66.6 (8.2) | 70.0 (9.0) | <0.001c |

| Range | 43.0–83.9 | 41.5–81.8 | 41.9–91.3 | 36.2–90.1 | ||

| Sex, male, n (%) | 45 (40.9) | 40 (58.8) | 0.020c | 191 (73.5) | 83 (77.6) | 0.411 |

| Education, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.6 (2.3) | 16.1 (2.5) | 0.137 | 16.0 (2.4) | 16.1 (2.5) | 0.909 |

| Range | 12–20 | 12–20 | 8–20 | 12–20 | ||

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.170 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.096 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.9) | ||

| Black | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| More than 1 race | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.5) | 4 (3.7) | ||

| White | 107 (97.3) | 68 (100) | 251 (96.5) | 99 (92.5) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | ||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.5) | 0.660 | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.288 |

| Non-Hispanic | 105 (95.5) | 66 (97.0) | 254 (97.7) | 105 (98.1) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (3.6) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Disease duration, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.4 (4.6) | 8.5 (4.7) | 0.003c | 8.0 (5.9) | 8.9 (5.3) | 0.188 |

| Range | 0.6–30.4 | 0.3–21.2 | 0.6–32.8 | 0.9–23.8 | ||

| MDS-UPDRS Part III score | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 20.1 (10.1) | 23.5 (10.0) | 0.030c | 26.2 (11.9) | 27.2 (10.1) | 0.462 |

| Range | 3.0–64.0 | 5.0–48.0 | 3.0–66.0 | 9.0–57.0 | ||

| Modified Hoehn & Yahr | ||||||

| Median | 2 | 2 | <0.001c | 2 | 2 | 0.024c |

| Range | 1–4 | 1–4 | 1–5 | 1–4 | ||

| LEDD, mg/d | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 416.1 (377.0) | 670.8 (422.0) | <0.001c | 557.6 (440.4) | 690.1 (464.7) | 0.010c |

| Range | 0–2318.0 | 0–1990.0 | 0–2328.0 | 0–2876.0 | ||

| GBA, N (%) | 7 (6.4) | 6 (8.8) | 0.540 | 22 (8.4) | 10 (9.4) | 0.777 |

| APOE ε4+, N (%) | 21 (19.1) | 16 (23.5) | 0.478 | 60 (23.3) | 26 (24.8) | 0.760 |

| Total follow-up time, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (2.3) | 4.1 (1.9) | 0.322 | 3.6 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.0) | 0.047c |

| Range | 0.8–9.2 | 1.0–8.0 | 0.8–9.3 | 1.0–8.7 | ||

| MoCA, total score | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 27.0 (1.8) | 25.8 (2.2) | <0.001c | 24.2 (2.4) | 23.5 (2.5) | 0.010c |

| Range | 21–30 | 21–29 | 17–29 | 17–29 | ||

Abbreviations: GBA = glucocerebrosidase gene; LEDD = levodopa equivalent daily dose; MDS-UPDRS = Uniform Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, Movement Disorders Society revision; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PDD = Parkinson disease dementia; PD-MCI = Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment; PD-NCI = Parkinson disease with no cognitive impairment.

p Values based on 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables, Kruskal-Wallis test for ordinal variables, and χ2 tests for categorical variables, with Bonferroni or Dunn test used for post hoc pairwise analyses.

p Values based on t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Significant at p < 0.05.

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

All study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at each participating site, and standard protocol approvals, registrations, and informed participant consents were obtained.

Motor and Cognitive Diagnoses

Study procedures, including clinical examinations, comprehensive neuropsychological assessments, and diagnostic consensus conferences, are described in detail elsewhere.27 Briefly, at baseline and follow-up visits, all participants underwent clinical examination, including structured assessment of PD motor symptoms (Uniform Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, Movement Disorders Society revision [MDS-UPDRS] Part III score, and Modified Hoehn & Yahr stage), symptom history, medications, focused past medical history, environmental exposures, family history, and neuropsychological testing. Participants were reviewed at diagnostic consensus conferences, which were attended by at least 2 movement disorders specialists, a neuropsychologist, and study personnel. PD participants who met UKBB criteria for PD were given a cognitive diagnosis of PD-NCI, PD-MCI following level II criteria,29 or PDD,31 according to published criteria.

Definition of Cognitive Progression Groups

Participants were identified as progressors if (1) they were PD-NCI at baseline and PD-MCI or PDD at their final study visit or (2) if they were PD-MCI at baseline and PDD at their final study visit. Participants who were PD-NCI or PD-MCI at both baseline and final study visits were considered stable. Participants with missing longitudinal data, including those who were lost to follow-up, were excluded from the analyses focused on cognitive progression (eTable 2; eResults).

Creating the Executive Functioning Composite

Executive functioning tests administered at baseline at all sites included the Trail Making Test Parts A and B, Digit Symbol subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Revised, Letter-Number Sequencing, Semantic Fluency (animal naming), and Phonemic Fluency (F and L). Executive functioning scores from the entire baseline sample were used to create the PaCEF to capture the full range of performance. Raw scores were recoded into ordinal variables with 10 categories each, maintaining the distribution as much as possible with an emphasis on preserving the variability at the tails32 and maintaining at least 10 participants in each category (eFigure 1). The ordinal baseline scores were then entered into a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the diagonally weighted least squares method of estimation to create a theory-driven measure of executive functioning. Model fit was determined using the comparative fit index (CFI; >0.95 indicates good fit33), which compares the postulated and baseline models and measures the relative improvement in fit; the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; >0.95 indicates good fit33), which measures a relative reduction in misfit per degree of freedom; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; <0.05 indicates good fit33), which measures how far a postulated model is from a perfect model. Each ordinal test score was first weighted by the standardized factor loading, and the weighted test scores were summed to create the PaCEF. An online PaCEF calculator and R code are available in the Supplement.

Statistical Models

Our first set of analyses characterized the change in cognition over time for participants who were PD-NCI at baseline and were stable, PD-NCI at baseline and progressed, PD-MCI at baseline and were stable, and PD-MCI at baseline and progressed. To accomplish this, we conducted linear mixed models with random intercepts and slopes as well as fixed effects of baseline diagnosis (PD-NCI, PD-MCI) × progression group (stable, progressed) × time, all 2-way interactions, and covariates of age (centered at 66.4 years), sex, education (centered at 16.1 years), disease duration (years since symptom onset centered at 7.9 years), disease severity (MDS-UPDRS Part III score centered at 24.9), and site (Johns Hopkins, Portland, Seattle, Stanford) (i.e., , where i = participant and j = years since baseline). Results with and without Bonferroni corrections for 12 cognitive tests are presented.

Our second set of analyses focused on understanding whether baseline PaCEF score predicts time to progression (i.e., time to PD-MCI/PDD for PD-NCI individuals at baseline; time to PDD for PD-MCI individuals at baseline) using accelerated failure time models with a Weibull distribution. Analyses adjusted for age, sex, education, disease duration, disease severity, site, and total study follow-up time. Survival analyses were used to confirm time to progression differences between individuals with low vs high PaCEF scores, defined by median splits. Results with and without Bonferroni corrections are presented.

Our third set of analyses calculated the sample sizes required for future clinical trials to detect cognitive decline in PD-NCI and PD-MCI participants who were stable vs progressed using the PaCEF.34 Briefly, an unadjusted linear mixed model with restricted maximum likelihood relating change in test score to time since study entry was fitted to the longitudinal data. Estimates of slopes and between- and within-person variability to detect a 25% or 50% reduction in slope in 1 or 2 years were extracted assuming 80% power, 5% probability of type I error, and dropout of 10% per year. Sample size estimates and confidence intervals were made comparing slopes of participants who were stable vs progressors, which represents the sample size needed to detect a treatment effect compared with what is achievable with treatment (i.e., the slopes of the stable participants are the upper limit expected within the course of the disease). All analyses were repeated with the MoCA; individual tests forming the PaCEF; the Judgment of Line Orientation (JLO), which is a measure of visuospatial function; a language measure based on crosswalked scores35 from the Boston Naming Test and Multilingual Naming Test; and Immediate and Delayed Recall scores from the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised, which are measures of memory. Analyses were performed using Stata 17.0 and R 4.2.2.

Data Availability

Anonymized data will be made available on request to qualified investigators who have institutional review board approval and a Data Usage Agreement with the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, VA Portland, Stanford University, and Johns Hopkins University.

Results

Of 1,057 participants screened at baseline, 39 were excluded due to a non-PD diagnosis, 12 were excluded for not meeting UKBB criteria, and 165 were excluded for not having complete baseline EF data, leaving a total of 841 participants (Table 1A). Excluded participants were older, had longer disease duration and more severe motor symptoms, and were more likely to have dementia (eResults; eTable 2A). A stepwise increase in age, disease duration, MDS-UPDRS Part III score, Modified Hoehn & Yahr stage, and percentage of male participants and a stepwise decrease in MoCA were observed when the comparison included PD-NCI to PD-MCI to PDD participants. PDD participants were significantly more likely to be glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA) carriers compared with both PD-NCI and PD-MCI participants. The proportion of APOE ε4 carriers did not significantly differ across cognitive groups.

Creating the PaCEF

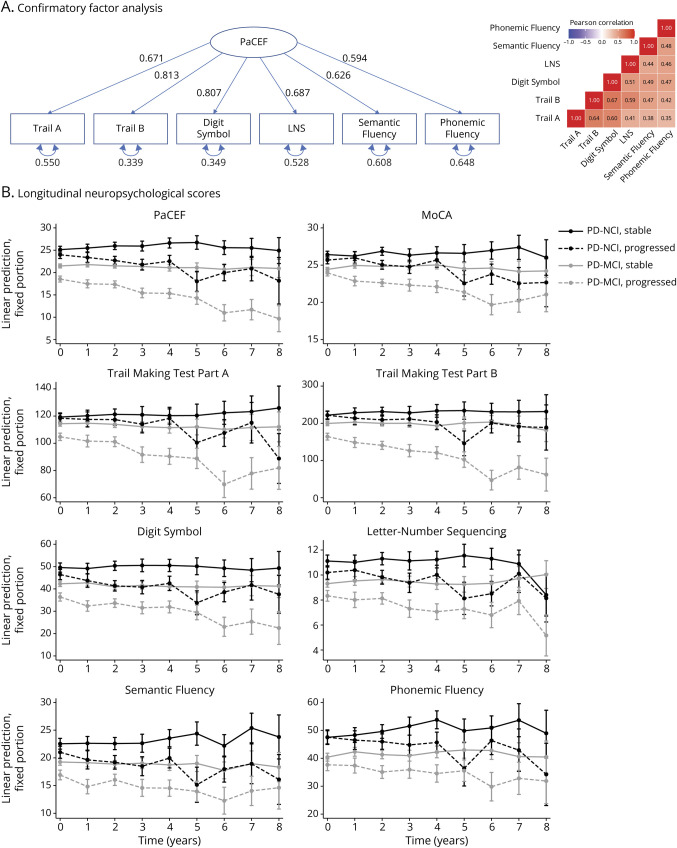

CFA yielded a single-factor model of executive functioning with excellent fit (CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.989, and RMSEA = 0.044; Figure 1A), providing support for the creation of the PaCEF.

Figure 1. Creation of and Longitudinal Change in the PaCEF.

(A) Confirmatory factor analysis used to create the PaCEF and (B) neuropsychological scores over time. PaCEF = Parkinson's Disease Composite of Executive Functioning.

Change in Neuropsychological Scores Over Time

We next examined the longitudinal sample to understand neuropsychological scores over time. Of the 841 participants with baseline data, 110 were excluded from longitudinal analyses as they already had PDD at baseline, 185 did not have longitudinal data available, and 1 had an unknown cognitive diagnosis at follow-up, leaving a total of 545 participants for analysis (Table 1B). There were no significant demographic or clinical differences between non-demented participants who were included vs excluded from longitudinal analyses (eResults; eTable 2B). Linear mixed models examining the interaction between baseline diagnosis, progression group, and time showed that those who were NCI at baseline and were stable showed significant improvements in PaCEF, Semantic Fluency, and Phonemic Fluency over time although only Phonemic Fluency was significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (Table 2A; Figure 1B; eTable 3). By contrast, those who were NCI at baseline and progressed to PD-MCI or PDD showed significant declines over time on the PaCEF, MoCA, Trail Making Test Parts A and B, Digit Symbol, Letter-Number Sequencing, and Semantic Fluency; after correcting for multiple comparisons, PaCEF, MoCA, Trail Making Test Part B, and Digit Symbol remained significant. Those who were PD-MCI at baseline and stable did not show significant score changes on any of the measures. Finally, those who were PD-MCI at baseline and progressed to PDD showed significant declines on all measures and all measures except Phonemic Fluency remained significant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Cognitive Score (A) Changes Over Time Within Each Group and (B) Ability to Predict Time to Progression

| (A) Cognitive score changes over time within each group | ||||||||

| PD-NCI at baseline | PD-MCI at baseline | |||||||

| Stable | Progressed | Stable | Progressed | |||||

| Estimate (SE) | p Value | Estimate (SE) | p Value | Estimate (SE) | p Value | Estimate (SE) | p Value | |

| PaCEF | +0.246 (0.098) | 0.012 | −0.546 (0.122) | <0.001c | −0.003 (0.097) | 0.978 | −0.821 (0.115) | <0.001c |

| MoCA | +0.086 (0.076) | 0.258 | −0.297 (0.096) | 0.002c | +0.084 (0.074) | 0.260 | −0.486 (0.089) | <0.001c |

| TMT Part A | +0.333 (0.540) | 0.537 | −1.694 (0.676) | 0.012 | −0.689 (0.534) | 0.197 | −3.941 (0.633) | <0.001c |

| TMT Part B | +1.793 (1.432) | 0.211 | −5.259 (1.803) | 0.004c | −0.557 (1.424) | 0.696 | −13.086 (1.670) | <0.001c |

| Digit Symbol | +0.134 (0.242) | 0.579 | −1.351 (0.299) | <0.001c | −0.299 (0.236) | 0.206 | −1.461 (0.279) | <0.001c |

| LNS | +0.026 (0.052) | 0.619 | −0.166 (0.066) | 0.013 | +0.056 (0.051) | 0.268 | −0.191 (0.059) | 0.001c |

| Semantic Fluency | +0.289 (0.125) | 0.020 | −0.452 (0.159) | 0.005 | −0.058 (0.123) | 0.636 | −0.446 (0.145) | 0.002c |

| Phonemic Fluency | +0.963 (0.275) | 0.001c | −0.626 (0.342) | 0.067 | +0.427 (0.268) | 0.111 | −0.663 (0.317) | 0.037 |

| (B) Ability of baseline cognitive score to predict time to progression | ||||||

| PD-NCI at baseline Progressors vs stable |

PD-MCI at baseline Progressors vs stable |

|||||

| TR | 95% CI | p Value | TR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| PaCEFa | 1.32 | 1.04–1.67 | 0.024 | 1.58 | 1.40–1.79 | <0.001c |

| MoCAa | 1.21 | 1.01–1.46 | 0.042 | 1.17 | 1.04–1.32 | 0.010 |

| TMT Part Aa,b | 1.06 | 0.83–1.34 | 0.649 | 1.16 | 1.08–1.23 | <0.001c |

| TMT Part Ba,b | 1.14 | 0.87–1.49 | 0.786 | 1.33 | 1.23–1.44 | <0.001c |

| Digit Symbola | 1.21 | 1.00–1.45 | 0.045 | 1.41 | 1.25–1.60 | <0.001c |

| LNSa | 1.15 | 0.97–1.38 | 0.106 | 1.17 | 1.05–1.30 | 0.005 |

| Semantic Fluencya | 1.23 | 1.02–1.49 | 0.031 | 1.32 | 1.18–1.50 | <0.001c |

| Phonemic Fluencya | 1.04 | 0.89–1.21 | 0.638 | 1.18 | 1.04–1.35 | 0.009 |

Abbreviations: LNS = Letter-Number Sequencing; MDS-UPDRS = Uniform Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, Movement Disorders Society revision; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PaCEF = Parkinson's Disease Composite of Executive Functioning; PD-MCI = Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment; PD-NCI = Parkinson disease with no cognitive impairment; TMT = Trail Making Test; TR = standardized time ratio.

Results control for age, sex, education, disease duration, disease severity (MDS-UPDRS Part III), site, and total follow-up time.

Scores were converted to standardized scale (SD = 1) to facilitate comparison of TRs across measures (part B).

Scores were reversed so that higher scores = better performance across all measures.

p < 0.05 after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Validating the PaCEF: Predicting Clinical Progression

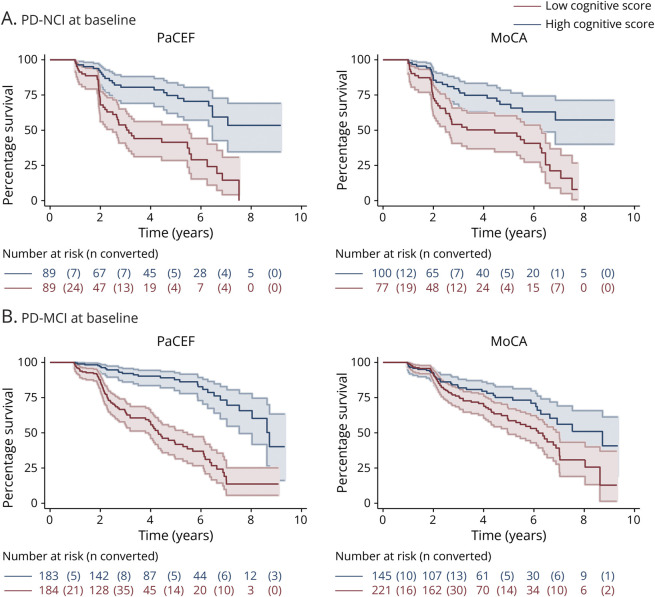

When predicting time to progression, higher scores on the MoCA, PaCEF, Digit Symbol, and Semantic Fluency were associated with longer time to PD-MCI or PDD in those who were PD-NCI at baseline (Table 2B); however, none of these tests remained significant predictors of time to progression after correcting for multiple comparisons. For those who had PD-MCI at baseline, higher scores on all measures were significantly associated with longer time to PDD (Table 2B); after correcting for multiple comparisons, MoCA, Letter-Number Sequencing, and Phonemic Fluency were no longer significant. Notably, the PaCEF showed the strongest association with time to PDD (standardized time ratio: 1.58), highlighting its utility. A median split on the PaCEF (PD-NCI low vs high cognitive score cutoff: 25; PD-MCI low vs high cognitive score cutoff: 20) and the MoCA (PD-NCI low vs high cognitive score cutoff: 26; PD-MCI low vs high cognitive score cutoff: 24) were used to visualize time to progression using Kaplan-Meier curves, and the distinction between high and low scorers was larger using the PaCEF than using the MoCA, especially for those who were PD-MCI at baseline (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Time to Cognitive Progression Based on Baseline PaCEF and Baseline MoCA Scores.

Kaplan-Meier curves depicting time to cognitive progression in (A) Parkinson's disease with no cognitive impairment (PD-NCI) at baseline and (B) Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI) at baseline comparing those with low and high cognitive scores on the PaCEF and MoCA. MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; PaCEF = Parkinson's Disease Composite of Executive Functioning.

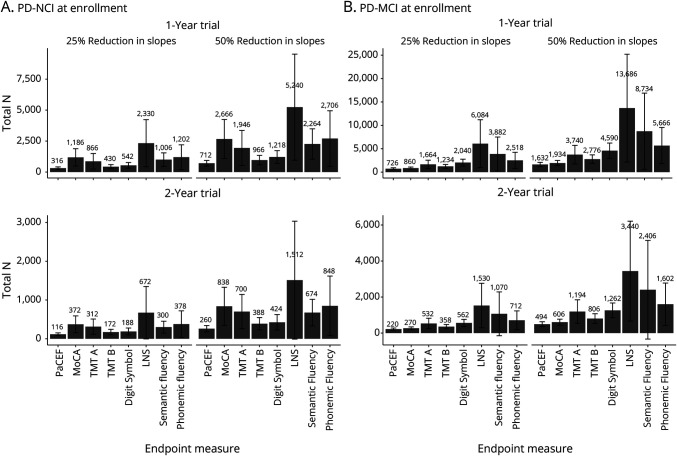

Required Sample Sizes for Clinical Trials

The required sample sizes to achieve 80% power for 1- and 2-year trials enrolling PD-NCI and PD-MCI participants using the PaCEF, MoCA, and PaCEF subtests as endpoints are shown in Figure 3. Sample size comparisons demonstrate a clear advantage for the PaCEF as the total number of participants required is 73% smaller than what would be required if the MoCA is used for 1-year trials enrolling PD-NCI participants, 69% smaller for 2-year trials enrolling PD-NCI participants, 16% smaller for 1-year trials enrolling PD-MCI participants, and 18% smaller for 2-year trials enrolling PD-MCI participants, assuming a 25% or 50% reduction in slopes. The advantage of using PaCEF as the endpoint is even greater when compared to sample sizes estimated with individual PaCEF subtests, as the required sample size with PaCEF is 27%–86% smaller than what would be required if individual PaCEF subtests are used for 1-year trials enrolling PD-NCI participants, 33%–83% smaller for 2-year trials enrolling PD-NCI participants, 41%–88% smaller for 1-year trials enrolling PD-MCI participants, and 39%–86% smaller for 2-year trials enrolling PD-MCI participants, assuming a 25% or 50% reduction in slopes.

Figure 3. Sample Size Estimates for Future PD Trials Based on Neuropsychological Endpoint Measures.

Estimates of required sample size targeting (A) PD-NCI and (B) PD-MCI at enrollment. Estimates are provided for 1- and 2-year trials detecting 25% and 50% reductions in slopes. Note that the y-axis range differs from row to row. PD = Parkinson disease; PD-MCI = Parkinson disease with mild cognitive impairment; PD-NCI = Parkinson disease with no cognitive impairment.

All results were similar when excluding GBA carriers (eResults; eTable 4; eFigures 2 and 3). Results when examining visuospatial, language, and memory domains showed mostly nonsignificant score changes in all groups after correcting for multiple comparisons; mostly nonsignificant predictions of time to progression; and poor model fit precluding estimates of clinical trial sample sizes or estimates that are several times larger than those obtained with the PaCEF (eResults; eTable 5; eFigure 4).

Discussion

Because there is a lack of an optimal cognitive outcome measure for clinical trials focused on cognition in PD, we leveraged neuropsychological data from 841 PD participants across 4 sites, 545 of whom had longitudinal data, to create the PaCEF. After identifying a model of executive functioning with excellent fit, we showed that PD participants who progressed in cognitive severity also showed expected declines on the PaCEF, highlighting the PaCEF's sensitivity to change. Importantly, baseline PaCEF scores, but not baseline MoCA scores, were able to predict time to progression in PD-MCI participants. Sample size comparisons demonstrated an advantage of using the PaCEF as a clinical trial endpoint as the required sample sizes were 69%–73% and 16%–18% smaller than would be required if the MoCA was used for clinical trials enrolling PD-NCI and PD-MCI participants, respectively. Taken together, our results demonstrate the utility of using the PaCEF for clinical trials targeting cognition in PD.

Because there are no disease-modifying therapies for PD, trials are instead focused on specific PD symptoms. The onset of cognitive impairment in PD varies greatly, with some individuals experiencing cognitive impairment before diagnosis and other individuals maintaining normal cognition decades after diagnosis. There is also substantial variability in the course of cognitive decline.6 For example, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) carriers have lower rates of dementia and better cognitive performance than non-LRRK2 carriers with PD,36 whereas GBA carriers have faster cognitive decline, are at higher risk of progression to dementia, and have higher prevalence of dementia than non-GBA carriers with PD.37 Our results were similar when including and excluding GBA carriers. Given that it is possible for patients with PD to maintain normal cognition until death and that the predictors of cognitive decline in sporadic PD are poorly understood, it is intuitive for trials of symptomatic therapies for cognitive impairment to enroll those who already show some degree of cognitive impairment. For these trials, our results highlighting the PaCEF's sensitivity to change and its ability to predict time to progression demonstrate a clear benefit of using the PaCEF, rather than the MoCA, individual PaCEF components, or tests assessing visuospatial, language, or memory ability, as the primary outcome.

Although we focused only on executive functioning to create the PaCEF, there is notable heterogeneity in cognitive profiles in PD.38 A meta-analysis on the cognitive profile of non-demented PD showed similar effect size differences between PD and healthy control participants in executive functioning, verbal memory, and visuospatial ability.39 In addition, the dual-syndrome hypothesis states that executive dysfunction may be an early process related to dopaminergic degeneration in PD, whereas impairments in posterior cortical deficits, including visuospatial functioning, may be more indicative of rapidly progressive cognitive decline.40 Thus, it is possible that there are subgroups of PD for whom posterior cortical functioning would be a better predictor of cognitive progression. However, previous research has shown that when comparing subtypes, those with posterior cortical impairments and those with more global deficit demonstrated similarly steep subsequent decline on attention and executive tasks.41 Furthermore, given the nature of the underlying pathology of PD, even subtypes with relatively greater posterior-cortical declines are likely to have at least some decline in attention/executive functions. In studies where posterior cortical decline was reported to be most strongly associated with progression to dementia, frontal executive processes were still likely involved, as the tests used to measure posterior cortical functioning were often Semantic Fluency and Clock Drawing, both of which draw heavily from executive functions. In our study, we demonstrated that the PaCEF changed significantly in PD-NCI and PD-MCI participants who progressed, whereas performance on the JLO, a measure of visuospatial ability, did not significantly change in any group and the JLO did not significantly predict time to progression. The JLO alone may not be sensitive enough to detect progression as composites combining scores from several tests generally provide more statistical power, but the number of validated visuospatial tests is relatively small compared with the number of validated executive functioning tests. This makes it much more difficult to create a visuospatial composite for clinical trial use.

Our sample size analyses demonstrated that the required sample size for 1- and 2-year trials enrolling PD-MCI participants could be reduced by 16%–18% if the PaCEF is used as the primary outcome instead of the MoCA and by 39%–88% if the PaCEF is used instead of individual PaCEF components. This is important because the number of subjects enrolled into a trial is a major driver of increasing costs.42 The number of functioning trial sites is limited and trial recruitment is a major challenge, especially when considering the screen failure rate in clinical trials can be quite high. An additional consideration for recruitment is that both patients and their caregivers are often required in clinical trials for cognitive impairment in neurodegenerative disease. Even though the MoCA only takes ∼10 minutes to complete, in contrast to the ∼25 minutes required for all the tests forming the PaCEF, the increased costs associated with recruiting more participants into a larger trial using the MoCA would substantially outweigh a smaller trial with a longer cognitive battery. Given the recent estimate of a pivotal trial cost of $39,467 per patient in CNS clinical trials,43 a reduction of 134–302 PD-MCI participants in a 1-year trial targeting 25% and 50% reductions in slopes (Figure 3B) could potentially save approximately $5 million to $12 million for the trial.

Although the PaCEF was designed for PD, the PaCEF may also be beneficial for clinical trials focused on dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), which shares the same primary underlying neuropathology as PD (i.e., aggregation of intracellular α-synuclein44) and has similar rates of cognitive and motor decline as PDD.45 DLB is clinically defined by the presence of dementia in addition to 1 (possible DLB) or at least 2 (probable DLB) core features (i.e., fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and parkinsonism),46 although the distinction between PD and DLB is debated.47 There are no disease-specific treatments currently approved for DLB by the US Food and Drug Administration48 or the European Medicines Agency, but there is growing interest in DLB drug development49 with cognition being the target for 50% of DLB drugs currently in the development pipeline.49 However, just as with PD, most DLB clinical trials are not using primary endpoints that are disease-specific or validated for the DLB population.49 Given the shared underlying disease mechanism between PD and DLB, the PaCEF may also be a useful endpoint for DLB trials focused on cognition.

There are several limitations to consider. First, our sample consisted of primarily highly educated non-Hispanic White individuals with access to large university settings, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Second, performance on the measures forming the PaCEF partially informed cognitive diagnoses (i.e., the comprehensive neuropsychological batteries used at each site included PaCEF tests and tests for other domains). Although this may raise concerns for some degree of circularity, there was variability in the degree of score change from test to test (Table 1A; Figure 1B). Thus, it was not necessarily a given that the PaCEF would show expected score declines in those who progressed and, indeed, scores from non-executive domains largely did not show significant declines. In addition, our use of same measures to define clinical status and detect change is akin to using the gold standard practice of using the MDS-UPDRS Part III to define motor severity and measure impact on motor symptoms. Third, although the PaCEF predicted conversion to dementia, diagnosis of dementia requires additional information regarding independence on instrumental activities of daily living, which will need to be separately measured in PD clinical trials. Relatedly, we aimed to include a full range of cognitive function and thus included PDD in the development of the PaCEF. However, the inclusion of PDD increases the chances of missing data due to advancing cognitive, motor, and sensory impairment (eTable 2; eResults). Thus, the generalizability of the PaCEF may be compromised for those at more advanced stages of PD. Fourth, although participants completed neuropsychological testing in the ON dopaminergic medication state, motor functioning can affect performance on 3 of the 6 measures that form the PaCEF (i.e., Trail Making Test Part A, Trail Making Test Part B, and Digit Symbol). Fifth, alternate forms of the PaCEF measures were not used, which could lead to practice effects. Indeed, this likely explains the improved performance on the PaCEF and other measures in the PD-NCI group who remained cognitively stable (Table 2A; Figure 1B). However, the absence of or reduction in practice effects has been shown to reflect subtle deficits in learning and memory, and alternate test forms do not completely remove practice effects.50 Sixth, although we examined visuospatial, language, and memory scores, we were unable to create composite scores for these other domains due to varying neuropsychological batteries. Finally, the PDCGC did not consistently recruit healthy control participants and we were thus unable to examine PaCEF changes in a control group.

Despite the growing interest and need for developing therapeutics addressing cognitive decline in PD, the outcomes used in current clinical trials in PD are not specifically designed for or validated in PD. Here, we demonstrate that the PaCEF is a cognitive composite measure of executive functioning that shows excellent fit in PD, that the PaCEF predicts time to progression in PD-MCI, and that use of the PaCEF can substantially reduce the sample size required for clinical trials to detect effects.

Glossary

- ADASCog

Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale—Cognitive Subscale

- CFA

confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI

comparative fit index

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- GBA

glucocerebrosidase gene

- JLO

judgment of line orientation

- LRRK2

leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- MDS-UPDRS

Uniform Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale, Movement Disorders Society revision

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PD

Parkinson disease

- PDCGC

Parkinson's Disease Cognitive Genetics Consortium

- PDD

PD dementia

- PD-MCI

PD with mild cognitive impairment

- PD-NCI

PD with no cognitive impairment

- RMSEA

root mean square error of approximation

- SAT

Sustained Attention Test

- TLI

Tucker-Lewis index

- UKBB

UK Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank Diagnostic

Appendix. Authors

| Name | Location | Contribution |

| Christina B. Young, PhD | Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Brenna Cholerton, PhD | Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine; Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; analysis or interpretation of data |

| Alena M. Smith, BS | Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Marian Shahid-Besanti, MS | Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Carla Abdelnour, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content |

| Elizabeth C. Mormino, PhD | Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine | Analysis or interpretation of data |

| Shu-Ching Hu, MD, PhD | Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System; Department of Neurology, University of Washington School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Kathryn A. Chung, MD, FRCP, FACP | Department of Neurology, Oregon Health and Science University; Portland Veterans Affairs Health Care System | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Amie Peterson, MD | Department of Neurology, Oregon Health and Science University; Portland Veterans Affairs Health Care System | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Liana Rosenthal, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Alexander Pantelyat, MD | Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Ted M. Dawson, MD, PhD | Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Joseph Quinn, MD | Department of Neurology, Oregon Health and Science University; Portland Veterans Affairs Health Care System | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Cyrus P. Zabetian, MS, MD | Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System; Department of Neurology, University of Washington School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data |

| Thomas J. Montine, MD, PhD | Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design |

| Kathleen L. Poston, MS, MD | Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine | Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; major role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; analysis or interpretation of data |

Study Funding

This study was supported by grants K99AG071837, R01NS115114, P50NS062684, U01NS102035, P30AG066515, P50NS38377, and U01NS082133 from the National Institute of Health and by grants AARFD-21-849349 from the Alzheimer's Association and I01 CX001702 from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Disclosure

E.C. Mormino is a paid consultant for Roche, Genentech, Eli Lilly, and Neurotrack. T.M. Dawson is a consultant for Mitokinin and Inhibikase Therapeutics, Inc., serves on the Board of Directors and is compensated as a founder of and consultant for Valted Seq, Inc., owns stock in American Gene Technologies International, Inc., owns stock options in Inhibikase Therapeutics, Inc., owns stock and stock options in Mitokinin, holds an ownership equity interest in Valted, LLC, is an inventor of technology of Neuraly, Inc. that has optioned from Johns Hopkins University, is a founder of and holds shares of stock options as well as equity in Neuraly, Inc. (now a subsidiary of D&D Pharmatech), holds shares of stock options as well as equity in D&D Pharmatech, and has a sponsored research agreement with Sun Pharma Advanced Research. K.L. Poston is a paid consultant for CuraSen Therapeutics, Inc. and Biohaven Pharmaceuticals. All other authors have no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Leroi I, McDonald K, Pantula H, Harbishettar V. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease: impact on quality of life, disability, and caregiver burden. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012;25(4):208-214. doi: 10.1177/0891988712464823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buter TC, van den Hout A, Matthews FE, Larsen JP, Brayne C, Aarsland D. Dementia and survival in Parkinson disease: a 12-year population study. Neurology. 2008;70(13):1017-1022. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306632.43729.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayram E, Batzu L, Tilley B, et al. Clinical trials for cognition in Parkinson's disease: where are we and how can we do better? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023;112:105385. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2023.105385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faust-Socher A, Duff-Canning S, Grabovsky A, et al. Responsiveness to change of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Mini-Mental State Examination, and SCOPA-Cog in non-demented patients with Parkinson's disease. Demen Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;47(4-6):187-197. doi: 10.1159/000496454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, et al. Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80(11 suppl 3):S54-S64. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aarsland D, Batzu L, Halliday GM, et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:47. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00280-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Hanlon CE, Farmer CM, Ryan J, Ernecoff NC. Clinical Outcome Assessments and Digital Health Technologies Supporting Clinical Trial Endpoints in Early Parkinson's Disease: Roundtable Proceedings and Roadmap for Research. RAND Corporation; 2023. Accessed February 2, 2024. rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CFA2550-1.html. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biundo R, Weis L, Bostantjopoulou S, et al. MMSE and MoCA in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: a multicenter 1-year follow-up study. J Neural Transm. 2016;123(4):431-438. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1517-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biglan K, Munsie L, Svensson KA, et al. Safety and efficacy of Mevidalen in Lewy body dementia: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2022;37(3):513-524. doi: 10.1002/mds.28879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albin RL, Müller MLTM, Bohnen NI, et al. α4β2* nicotinic cholinergic receptor target engagement in Parkinson disease gait-balance disorders. Ann Neurol. 2021;90(1):130-142. doi: 10.1002/ana.26102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dayal V, Grover T, Tripoliti E, et al. Short versus conventional pulse-width deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease: a randomized crossover comparison. Mov Disord. 2020;35(1):101-108. doi: 10.1002/mds.27863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kueper JK, Speechley M, Montero-Odasso M. The Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog): modifications and responsiveness in pre-dementia populations. A narrative review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(2):423-444. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D. Lewy body dementias. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1683-1697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00462-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoogland J, van Wanrooij LL, Boel JA, et al. Detecting mild cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease: comparison of neuropsychological tests. Mov Disord. 2018;33(11):1750-1759. doi: 10.1002/mds.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker H. Biomarkers to guide directional DBS for Parkinson's disease. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03353688. Accessed May 15, 2023. clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03353688.

- 16.Kletzel SL. rTMS to improve cognition in Parkinson's (TMSCogReP). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03836950. Accessed February 8, 2024. clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03836950.

- 17.Cognitive rehab for Parkinson's. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03836963. Accessed February 8, 2024. clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03836963.

- 18.Skorvanek M, Goldman JG, Jahanshahi M, et al. Global scales for cognitive screening in Parkinson's disease: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2018;33(2):208-218. doi: 10.1002/mds.27233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez FV, Kenney LE, Ratajska A, Jacobson CE, Bowers D. What does the Dementia Rating Scale-2 measure? The relationship of neuropsychological measures to DRS-2 total and subscale scores in non-demented individuals with Parkinson's disease. Clin Neuropsychol. 2023;37(1):174-193. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2021.1999505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pagonabarraga J, Kulisevsky J, Llebaria G, García-Sánchez C, Pascual-Sedano B, Gironell A. Parkinson's disease-cognitive rating scale: a new cognitive scale specific for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(7):998-1005. doi: 10.1002/mds.22007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernández de Bobadilla R, Pagonabarraga J, Martínez-Horta S, Pascual-Sedano B, Campolongo A, Kulisevsky J. Parkinson's disease-cognitive rating scale: psychometrics for mild cognitive impairment. Mov Disord. 2013;28(10):1376-1383. doi: 10.1002/mds.25568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosca EC, Simu M. Parkinson's disease-cognitive rating scale for evaluating cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 2020;10(9):588. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10090588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westbrook A, van den Bosch R, Määttä JI, et al. Dopamine promotes cognitive effort by biasing the benefits versus costs of cognitive work. Science. 2020;367(6484):1362-1366. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryman SG, Yutsis M, Tian L, et al. Cognition at each stage of Lewy body disease with co-occurring Alzheimer's disease pathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;80(3):1243-1256. doi: 10.3233/JAD-201187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Port RJ, Rumsby M, Brown G, Harrison IF, Amjad A, Bale CJ. People with Parkinson's disease: what symptoms do they most want to improve and how does this change with disease duration? J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(2):715-724. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung SJ, Lee HS, Kim H-R, et al. Factor analysis-derived cognitive profile predicting early dementia conversion in PD. Neurology. 2020;95(12):e1650-e1659. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cholerton BA, Zabetian CP, Quinn JF, et al. Pacific Northwest Udall Center of Excellence Clinical Consortium: study design and baseline cohort characteristics. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3(2):205-214. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mata IF, Johnson CO, Leverenz JB, et al. Large-scale exploratory genetic analysis of cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;56:211.e1-211.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litvan I, Goldman JG, Tröster AI, et al. Diagnostic criteria for mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: Movement Disorder Society Task Force guidelines. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):349-356. doi: 10.1002/mds.24893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibb WR, Lees AJ. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51(6):745-752. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(12):1689-1707; quiz 1837. doi: 10.1002/mds.21507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, et al. Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6(4):502-516. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9186-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equat Model. 1999;6:1-55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nash S, Morgan KE, Frost C, Mulick A. Power and sample-size calculations for trials that compare slopes over time: introducing the slopepower command. Stata J. 2021;21(3):575-601. doi: 10.1177/1536867X211045512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monsell SE, Dodge HH, Zhou XH, et al. Results from the NACC uniform data set neuropsychological battery crosswalk study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2016;30(2):134-139. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srivatsal S, Cholerton B, Leverenz JB, et al. Cognitive profile of LRRK2-related Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30(5):728-733. doi: 10.1002/mds.26161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szwedo AA, Dalen I, Pedersen KF, et al. GBA and APOE impact cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease: a 10-year population-based study. Mov Disord. 2022;37(5):1016-1027. doi: 10.1002/mds.28932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudhary S, Kumaran SS, Kaloiya GS, et al. Domain specific cognitive impairment in Parkinson's patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;75:99-105. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curtis AF, Masellis M, Camicioli R, Davidson H, Tierney MC. Cognitive profile of non-demented Parkinson's disease: meta-analysis of domain and sex-specific deficits. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;60:32-42. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kehagia AA, Barker RA, Robbins TW. Cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease: the dual syndrome hypothesis. Neurodegener Dis. 2013;11(2):79-92. doi: 10.1159/000341998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pourzinal D, Yang J, Sivakumaran K, et al. Longitudinal follow up of data-driven cognitive subtypes in Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav. 2023;13(10):e3218. doi: 10.1002/brb3.3218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martin L, Hutchens M, Hawkins C, Radnov A. How much do clinical trials cost? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(6):381-382. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore TJ, Heyward J, Anderson G, Alexander GC. Variation in the estimated costs of pivotal clinical benefit trials supporting the US approval of new therapeutic agents, 2015-2017: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e038863. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koga S, Sekiya H, Kondru N, Ross OA, Dickson DW. Neuropathology and molecular diagnosis of Synucleinopathies. Mol Neurodegener. 2021;16(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13024-021-00501-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez MC, Tovar-Rios DA, Alves G, et al. Cognitive and motor decline in dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease dementia. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2023;10(6):980-986. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88-100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berg D, Borghammer P, Fereshtehnejad SM, et al. Prodromal Parkinson disease subtypes: key to understanding heterogeneity. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(6):349-361. doi: 10.1038/s41582-021-00486-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sabbagh MN, Taylor A, Galasko D, et al. Listening session with the US Food and Drug Administration, Lewy Body Dementia Association, and an expert panel. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2023;9(1):e12375. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abdelnour C, Gonzalez MC, Gibson LL, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies drug therapies in clinical trials: systematic review up to 2022. Neurol Ther. 2023;12(3):727-749. doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00467-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young CB, Mormino EC, Poston KL, et al. Computerized cognitive practice effects in relation to amyloid and tau in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: results from a multi-site cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;15(1):e12414. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be made available on request to qualified investigators who have institutional review board approval and a Data Usage Agreement with the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, VA Portland, Stanford University, and Johns Hopkins University.