Abstract

All cells are subject to geometric constraints, such as surface area-to-volume (SA/V) ratio, that impact cell functions and force biological adaptations. Like the SA/V ratio of a sphere, it is generally assumed that the SA/V ratio of cells decreases as cell size increases. Here, we investigate this in near-spherical mammalian cells using single-cell measurements of cell mass and surface proteins, as well as imaging of plasma membrane morphology. We find that the SA/V ratio remains surprisingly constant as cells grow larger. This observation is largely independent of the cell cycle and the amount of cell growth. Consequently, cell growth results in increased plasma membrane folding, which simplifies cellular design by ensuring sufficient membrane area for cell division, nutrient uptake and deformation at all cell sizes.

Keywords: Cell size, cell cycle, plasma membrane, surface area-to-volume ratio, size scaling, cell surface

Surface area-to-volume (SA/V) ratio sets a theoretical maximum for various cell functions, including cell growth, nutrient uptake and shape changes 1–9. SA/V ratio is predominantly studied in unicellular organisms, where SA/V ratio can change with cell size and environmental conditions 10–13. In animals, cells that require high nutrient uptake or high capacity to deform typically display high SA/V ratio. For example, microvilli on the intestinal enterocytes increase the apical plasma membrane area significantly, which is considered critical for nutrient uptake 14. Similarly, T-lymphocytes display high plasma membrane area due to microvilli and membrane folds, which enables cell deformations necessary for tissue intravasation and migration 15,16. In the context of cell growth, the SA/V ratio is generally assumed to decrease as cell size increases. Because the ability of cells to take up nutrients can depend on their surface area, the decreasing SA/V ratio could impose an upper limit for cell size and cause size-dependency in cell growth 7,8,17. The decreasing SA/V ratio could also enable cell size sensing 13,18–20. Yet, little is known about the regulation of SA/V ratio during the growth and division of animal cells.

Changes in the ratio during cell growth are described by the cell size scaling of cell surface area. This is quantified as the scaling factor (exponent) of the power law:

| Eq (1) |

where is a constant and is the scaling factor. depicts isometric scaling, where surface area and cell volume grow at the same rate (i.e. SA/V ratio is constant). depicts ⅔-geometric scaling, as seen in perfect spheres, where the surface area grows at a slower rate than cell volume (i.e. SA/V ratio decreases as cells grow larger). ~⅔-geometric size scaling is observed in bacteria 10 and is expected to apply to animal cells, especially the cells are nearly spherical in shape. However, this model of size scaling cannot entirely explain cell behavior during proliferation. Proliferation under a steady state requires that cells, on average, double their volume and surface area within each cell cycle, and this requirement is not met by surface area that follows ⅔-geometric size scaling. Here we consider two competing size-scaling models for SA/V ratio in proliferating cells that cells may utilize to solve this problem (Fig. 1A):

Figure 1. Single-cell mass and surface protein measurements reveal isometric size-scaling of plasma membrane proteins in mammalian cells.

(A) Models for cell size-scaling of cell surface area in proliferating cells. Isometric size-scaling (orange) would result in cells accumulating surface area at the same rate as volume, resulting in a buildup of plasma membrane reservoirs as cells grow larger. These membrane reservoirs are required for cytokinesis, where the apparent surface area increases. Alternatively, cells could follow ⅔-geometric size-scaling of surface area (green), where the membrane reservoirs do not increase during growth, but additional membrane is added at the end of the cell cycle to support cytokinesis (blue). (B) The models in panel (A) can be distinguished by examining the power law scaling relationship between cell surface components and cell mass. (C) Representative single z-layer images of volume and surface labelled polystyrene beads, and of surface protein labeled L1210 and BaF3 cells. Scale bars denote 10 μm. (D) Scatter plots displaying the scaling between bead labeling and bead mass (top & middle), and between L1210 cell surface protein labeling and cell mass (bottom). Each opaque point represents a single bead/cell, black lines and shaded areas represent power law fits and their 95% confidence intervals, and dashed grey lines indicate isometric scaling (n>1000 beads/cells per experiment). (E) Quantifications of the scaling factor, b. Each dot represents a separate experiment (n>450 beads/cells per experiment), and error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Orange and green areas indicate 95% confidence intervals of volume or surface labeled bead data, respectively. See also Figs. S1–S2.

SA/V ratio could be cell-cycle dependent, so that cells display ⅔-geometric scaling of surface area during most of the cell cycle. In this case, the excess surface area needed for cell division would need to be produced at the end of each cell cycle, resulting in a scaling factor of >1 in during this period (Fig. 1B). This model is supported by the findings that the translation of lipid synthesis enzymes is upregulated at the end of the cell cycle and several lipid species accumulate from S-stage to M-stage 21–26. Alternatively, cells could produce volume and plasma membrane components at the same rate, resulting in a constant SA/V ratio, i.e. isometric size scaling of the plasma membrane components (scaling factor of 1, Fig. 1B). This model is supported by the observation that most cell organelles, transcripts and proteins scale isometrically with cell size 19,27–41.

Quantifying the area of the plasma membrane by imaging is difficult due to the various membrane folds and nanometer-scale structures 42. This has made studies of the SA/V ratio challenging in animal cells, where surface area is not defined by a rigid cell wall. Here, we overcome this challenge by quantifying cell surface localized plasma membrane components as a proxy for surface area, which we then compare to the size of the cells. This allows us to examine the size scaling and cell-cycle regulation of the SA/V ratio, as well as individual cell surface proteins, in mammalian cells. We reveal that cells exhibit approximately constant SA/V ratio as they grow larger. This causes cell size dependency in plasma membrane morphology and enables cell divisions and growth at all sizes. We propose that maintaining a constant SA/V ratio simplifies the regulation of surface area, resulting in a more robust cellular design.

RESULTS

Isometric size scaling of plasma membrane associated components in published data

We started by examining the production of plasma membrane associated components using a previously published dataset that links single-cell mass measurements with single-cell RNA-seq (Fig. S1A) 43. To obtain statistically rigorous size-scaling behaviors, we grouped genes together based on their GO-term association. On average, all cell transcripts displayed scaling factors of 0.91±0.001 and 0.85±0.001 (mean±SE) in L1210 (mouse lymphocytic leukemia) and FL5.12 (mouse pro–B lymphocytes) cells, respectively (Fig. S1B). In contrast, cell division associated transcripts super-scaled with cell size, validating that non-isometric scaling behaviors can be identified. However, transcripts associated with the external side of plasma membrane were not statistically different from all cell transcripts, as the plasma membrane associated transcripts displayed scaling factors of 0.87±0.07 and 0.88±0.04 (mean±SE) in L1210 and FL5.12 cells, respectively. Thus, the cell size scaling of plasma membrane associated mRNAs is near-isometric. This is consistent with the size scaling of most transcripts across various model systems 19,32,33,35–39, and similar to the size scaling of plasma membrane associated proteins in human cells 29. However, even if plasma membrane proteins are synthesized isometrically with cell size, they may not be inserted into the plasma membrane, as most plasma membrane components also localize to intracellular membranes 44. We therefore focused on examining the abundance of components specifically on the cell surface.

Proliferating mammalian cells display isometric size scaling of cell surface protein content

We established an approach for quantifying the abundance of cell surface proteins as a proxy for cell surface area, as ~50% of the plasma membrane consists of proteins 45. Our approach couples the suspended microchannel resonator (SMR), a cantilever-based single-cell buoyant mass sensor 46,47, with a photomultiplier tube (PMT) based fluorescence detection setup 48. This enables a measurement throughput of >10,000 single cells/hour (Fig. S2A–B) 49,50. We validated our approach’s sensitivity to distinguish different modes of size scaling by measuring spherical polystyrene beads that were labeled either throughout the volume of the beads or specifically on the surface of the beads (Fig. 1C). These two bead types displayed distinct size-scaling behaviors, with volume-labelled beads having a scaling factor of ~1 and surface-labelled beads having a scaling factor of ~0.6 (Figs. 1D & E). Notably, the beads had little size variability, indicating that our approach can separate distinct size-scaling behaviors even over small size ranges. Our approach uses buoyant mass as an indicator of cell size, but buoyant mass is also an accurate proxy for cell volume (Fig. S2C) and dry mass 51. Therefore, our size-scaling analyzes are reflective of both volume scaling and dry mass scaling.

To label cell surface proteins across the external side of the plasma membrane in live cells, we utilized a cell impermeable, amine reactive dye that is coupled to a fluorophore 52. Cell labeling was carried out on ice for 10 min to prevent plasma membrane internalization, and the surface-specificity of the labeling was validated with microscopy (Figs. 1C, S2D). Dead cells were excluded from final data analysis (Fig. S2E). As model systems for our work, we focused on suspension grown mammalian cell lines: L1210, BaF3 (mouse pro-B lymphocyte), S-HeLa (suspension grown human adenocarcinoma), OCI-AML3 (human myeloid leukemia), THP-1 (human monocytic leukemia) and FL5.12. These cells maintain near-spherical shape during growth (Figs. 1C, S2D), which makes these cells likely candidates to exhibit ⅔-geometric scaling.

We found that all cell types displayed isometric size scaling of surface protein content that was indistinguishable from the volume labeled beads (Fig. 2B & C). For example, L1210 and THP-1 cells displayed scaling factors of 0.90±0.03 and 1.01±0.05 (mean±95% CI), respectively. These results are consistent with the size scaling of mRNAs associated with the external side of plasma membrane (Fig. S1B). Pearson correlation values for the fitted scaling factors were high, R2 = 0.66±0.08 (mean±SD across all samples), and we verified that our results were not sensitive to outliers or the gating strategy (Fig. S2F–H). We also utilized an alternative cell surface protein labeling chemistry, where protein thiol groups are labeled using fluorescent coupled Maleimide 52. This approach yielded near-isometric scaling factors, similar to the surface amine labeling (Fig. S2I–K). Thus, when analyzing across all cells in a population, proliferating mammalian cells exhibit isometric rather than ⅔ geometric scaling of surface components despite their spherical shape.

Figure 2. Cell cycle-dependent effects on cell surface protein content.

(A) Top, the gating strategy used to separate cell cycle stages according to cell mass and geminin-GFP. Bottom, a scatter plot displaying the scaling between L1210 cell surface protein labeling and cell mass in G1 (red) and S&G2 (blue) stages. Each opaque point represents a single cell, lines represent power law fits to each cell cycle stage. (B) Quantifications of the scaling factor, b, in G1 (red) and S/G2 (blue) stages. Each dot represents a separate experiment, error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals (n>500 cells per experiment). Orange and green areas indicate 95% confidence intervals of volume or surface labeled bead data, respectively. p-values were obtained using Student’s paired t-test between G1 and S/G2 scaling factors. (C) Moving window analysis of the scaling factor, b, as a function of cell mass in indicated cell lines. Dark line and shaded areas represent the mean±SD of the scaling factor (N=4 independent experiments), green area depicts the cell size distribution, blue vertical line indicates typical G1/S transition size. (D) Cell surface protein content changes between identically sized G1 and S stage cells (left) or G2/M and cytokinetic cells (right). Each dot represents a separate experiment, error bars represent the compound SEM. p-values were obtained using Student’s t-test and reflect comparisons to 0. See also Fig. S3.

Cell cycle-specific effects in cell surface protein content

One way for cells to achieve isometric scaling at the population level is if the surface protein content varies with the cell cycle (Fig. 1B). To test this, we first separated G1 and S/G2 stages of the cell cycle using the fluorescent ubiquitination-based cell cycle indicator, geminin-GFP (Figs. 2A, S3A). We observed a cell cycle dependency in the size scaling of surface protein content in L1210, OCI-AML3 and FL5.12 cells, where G1 cells displayed higher scaling factors than S/G2 cells (Fig. 2B). However, all these scaling factors remained within the 95% confidence interval of the volume labeled bead data. To explore this further, we analyzed the size-scaling factors in a continuous moving window as cells grow and proceed in the cell cycle. This revealed that the scaling factor changes non-monotonically in all cell lines (Figs. 2C, S3B). The scaling factor increased when moving from small to large G1 cells, decreased during the S-phase, and increased again in the largest cells (G2/M). This suggests that cells alter their production of surface proteins and internal components proportionally, with more internal components being produced during S-phase. Importantly, by examining cells across different ploidy (Fig. S3C), we validated that these surface protein production dynamics could be attributed to cell cycle rather than nonlinear cell size dependent effects.

Cell cycle transitions could impose rapid changes in cell surface content. For example, cell divisions impose additional membrane requirements on the cells, which are estimated to be ~30% in a typical lymphocyte 52, and cells could meet this membrane requirement by a rapid expansion of membrane components during cytokinesis. To directly investigate this, we compared the cell surface protein content between identically sized cytokinetic (geminin-GFP negative) and G2/M (geminin-GFP positive) cells 52. We did not observe changes to cell surface protein content that would be systematic between cell lines and most cells did not increase their surface protein content with the entry to cytokinesis (Fig. 2D). Thus, the increased membrane requirement imposed by cytokinesis is unlikely to be met by membrane addition taking place specifically during cell division 52. We also investigated the G1/S transition using a similar approach, but we did not observe systematic changes shared by all cell lines (Fig. 2D).

Together, these results show that cells i) do not adopt ⅔-geometric size scaling of their surface components even in specific cell cycle stages and ii) do not radically alter their surface protein content at cell cycle transitions. However, cell cycle progression is still associated with changes in the relative production of cell surface proteins and internal components. For L1210 cells, changes in the relative production of cell surface proteins and internal components mirror the cell growth rates (Figs. S3C&D) 53. We also note that S-HeLa cells displayed different cell cycle-dependencies than other cell lines used in our study (Figs. 2D, S3B). This may reflect cell differentiation, as our other model systems originate from hematopoietic lineage.

Individual cell surface proteins display heterogenous size scaling and cell cycle-dependency

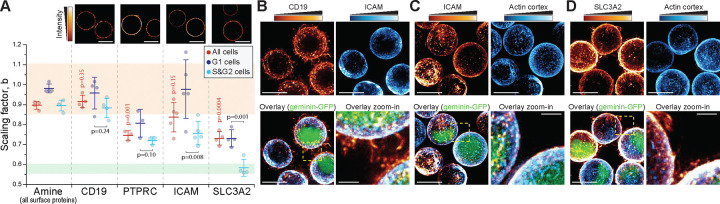

The cell size scaling of individual proteins could differ from the collective size scaling of all cell surface proteins, as shown for many intracellular proteins 27,29 and the plasma membrane localized cell polarity regulating PAR proteins 54. We selected 4 highly expressed proteins with a cluster of differentiation identifier (CD number) from our scRNA-seq data and used immunolabelling of live cell surfaces to analyze the size scaling of the individual proteins. Surface-specificity of the labeling was validated using microscopy (Fig. 3A, top). The proteins examined included amino acid transporters (Solute Carrier Family 3 Member 2 (SLC3A2), a.k.a. CD98), membrane receptors and signaling proteins (B-Lymphocyte Surface Antigen B4 (CD19); and Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Receptor Type C (PTPRC), a.k.a. CD45), and cell adhesion molecules (Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM1), a.k.a. CD54). Curiously, each protein displayed a distinct size-scaling behavior (Fig. 3A). For example, CD19 displayed near-isometric size scaling, which was identical to the overall surface protein labeling. In contrast, SLC3A2 displayed lower scaling factors (b~0.73 across all cells) and a cell cycle-dependency where S&G2 cells displayed ⅔-geometric size scaling (b~0.6, as in surface labeled beads). Also ICAM1 displayed a cell cycle-dependency where the scaling factors were high in G1 (b~1) but significantly lower in S/G2 (b~0.75). These results suggest the existence of cell size dependent amino acid uptake and cell adhesion specifically in S/G2 cells. More broadly, these results highlight that individual cell surface proteins are regulated independently of each other, resulting in heterogeneous size scaling and cell cycle-dependency.

Figure 3. Individual cell surface proteins display heterogeneity in their cell size-scaling.

(A) Top, representative single z-layer images of L1210 cell surface immunolabeling (N=2–3 independent experiments, n>40 cells). Bottom, quantifications of the scaling factor, b, for indicated cell surface proteins. Overall surface protein (amine) labeling is shown for reference. Data is shown for whole population (red), and separated G1 (dark violet) and S&G2 (light blue) stages. Each dot represents an independent experiment (n>500 cells), bars and whiskers represent mean±SD. Orange and green areas indicate 95% confidence intervals of volume or surface labeled bead data, respectively. p-values in red indicate Welch’s t-test between individual and overall protein labeling. p-values in black indicate Student’s paired t-test between G1 and S&G2 data for individual proteins. (B-D) Representative maximum intensity projections of immunolabelled live L1210 cells expressing LifeAct F-actin sensor. Immunolabeled membrane proteins can associate with actin cortex or membrane folds, but this association does not correlate with the protein’s size-scaling. Scale bars denote 10 μm, except in zoom-ins, where scale bars denote 2 μm. N=2–3 independent experiments and n>55 cells.

Next, we considered the mechanistic basis for the heterogeneity of scaling factors between individual plasma membrane proteins. Many plasma membrane proteins bind to the actin cortex, but folding of the plasma membrane spatially separates parts of the plasma membrane from the actin cortex. Consequently, the space available for plasma membrane proteins to bind the actin cortex could display ⅔-geometric scaling. We examined if the plasma membrane proteins with ⅔-geometric size scaling are exclusively colocalized with the actin cortex, whereas the membrane proteins with isometric size scaling are found also on membrane folds. To test this, we immunolabeled CD19, ICAM1 and SLC3A2 in L1210 cells expressing the LifeAct F-actin reporter. CD19, which displayed isometric size scaling, was clearly present on membrane folds and ruffles (Fig. 3B). In contrast, ICAM1, which displayed cell cycle-dependent size scaling, was excluded from the membrane folds and ruffles (Fig. 3B–C), as expected based on the protein’s known association with the actin cortex 55. However, we did not observe cell cycle-dependency in ICAM1’s localization, which argues against our hypothesis. Finally, SLC3A2, which displayed ⅔-geometric size scaling in S&G2 cells, was present on membrane folds and ruffles even in S&G2 cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, connection to the actin cortex does not explain the size scaling of individual plasma membrane proteins.

⅔-geometric size scaling of surface proteins does not arise following cell cycle exit

The isometric size scaling of plasma membrane protein content may be necessary for satisfying requirements imposed by cell divisions, as cells typically need to double their plasma membrane content to divide (Fig. 1A). If so, then non-proliferating cells could display ⅔-geometric size scaling of surface components (Fig. 4A). To examine the size scaling of plasma membrane proteins in the absence of cell divisions and cell cycle progression, we first studied FL5.12 cells that have entered quiescence due to IL-3 starvation 56, and THP-1 cells that have entered senescence due to treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib 29. Following a treatment to stimulate cell cycle exit, both cell lines displayed G1 arrest, as evaluated based on DNA content and Geminin-GFP protein levels (Figs. S4A&B). The models also exhibited cell size changes. Quiescence resulted in cell volume decrease, and senescence resulted in cell volume increase, when compared to proliferating control populations (Figs. S4C&D). Cell density decreased in senescent THP-1 cells, as seen in other senescent models 57, but cell density increased in quiescent FL5.12 cells (Figs. S4E&F). Both model systems retained near-spherical morphology following the cell cycle exit (Fig. 4B). In FL5.12 cells, cell cycle exit resulted in a scaling factor that was seemingly increased in comparison to proliferating control cells, although this change was not statistically significant (Figs. 4C, top). In THP-1 cells, cell cycle exit resulted in a scaling factor that was decreased in comparison to proliferating control cells (Figs. 4C, middle). However, the scaling factor in senescent THP-1 cells remained above 0.8 and thus significantly different from the ⅔ geometric size scaling. To support our findings in a more physiologically relevant model system, we studied CD14+ primary human monocytes. These cells are terminally differentiated and thus non-proliferative, yet approximately spherical in their morphology (Fig. 4B, bottom). The size scaling of plasma membrane protein content in the monocytes displayed significant sample-to-sample variation with an average scaling factor of 1.3 (Fig. 4C, bottom). Overall, these results indicate that cell proliferation, and the membrane requirements imposed by cell divisions, do not explain the isometric size scaling of plasma membrane contents. Instead, the isometric size scaling of plasma membrane contents may reflect a more fundamental cellular organization principle.

Figure 4. Near-isometric size-scaling of surface proteins is not limited to proliferating cells.

(A) Experimental hypothesis (left) and model systems (right & bottom). In proliferating cells, plasma membrane content approximately doubles every cell cycle to enable cytokinesis. Upon cell cycle exit, such requirement no longer exists, and the size-scaling of cell surface components could follow ⅔-geometric scaling. (B) Representative single z-layer images of cell surface amine labeling in proliferating and non-proliferating FL5.12 cells (top) and THP-1 cells (middle), and in non-proliferating primary human monocytes (bottom). Scale bars denote 10 μm. N=2 independent experiments, n>30 cells. (C) Quantifications of the scaling factor, b. Each dot represents a separate experiment (N=4–5), bar and whiskers represent mean±SEM. p-values were obtained using Welch’s t-test when comparing proliferation states to each other and using Student’s one sample t-test when comparing non-proliferating cells to ⅔ geometric size-scaling. See also Fig. S4.

Excessive cell size increases do not downregulate cell surface expansion

We next considered the possibility that the isometric size scaling of plasma membrane protein content is only maintained when cells are within a normal size range. Following excessive cell size increases, feedback mechanisms may decrease the rate of plasma membrane expansion to prevent excessive plasma membrane accumulation (Fig. 5A). We therefore compared a model where cells adjust their surface area expansion following excessive cell size increases to a model where size scaling of surface area remains constant at all sizes. We treated L1210 and THP-1 cells with Barasertib, an Aurora B inhibitor which prevents cytokinesis, to generate polyploid cells with large cell size increases 53. We then combined cell populations at different stages of polyploidization, labelled cell surface proteins and analyzed the cells for size scaling (Figs. 5B–D). In both L1210 and THP-1 cells, despite ~10-fold increases in cell size, the size-scaling factor was independent of cell size and ploidy (Figs. 5E&F). Thus, we did not observe feedback mechanisms that would decrease the rate of plasma membrane expansion as cells grow excessively large.

Figure 5. Excessive cell growth is coupled with plasma membrane folding and isometric size-scaling of cell surface area.

(A) Schematic of competing models. If cells aim to maintain a fixed degree of plasma membrane folding, excessive cell size increases should decrease the scaling factor (green). However, if cells produce surface components independently of the degree of plasma membrane folding, the scaling factor should be independent of cell size (orange). (B) Experimental setup. (C) A scatter plot of geminin-GFP as a function of cell mass in L1210 cells of different ploidy. (D) A scatter plot displaying the scaling between cell mass and surface amine labeling in L1210 cells. Each opaque point represents a single cell colored according to its ploidy. Power law fits are shown separately for each ploidy (n>1000 cells per ploidy). (E) Quantifications of the scaling factor, b, across L1210 cells of different ploidy. Each small, opaque point indicates an independent experiment (N=9). Large, dark points and error bars represent mean±SD. p-value obtained using ANOVA. (F) Same as panel (E), but data is for THP1 cells (N=7). (G) Top, representative single z-layer images of membrane lipid labeling. Scale bars denote 10 μm. Bottom, a scatter plot displaying the scaling between cell volume and plasma membrane lipid labeling in L1210 cells of various ploidy. Each opaque point represents a single cell, power law fits are shown separately for each experiment (N=2 independent experiments, n=190 and 124 cells). (H) Representative SEM images of small and large (polyploid) L1210 cells. Scale bars denote 2 μm. N=3 independent experiments, n=63 cells. (I) Representative TEM images of small and large (polyploid) L1210 cells. Scale bars denote 2 μm. N=2 independent experiments, n=65 cells. See also Fig. S5.

Next, we examined the size scaling of plasma membrane lipids to ensure that our results are not limited to the protein content of the membrane. Because lipid labeling approaches also label cell’s internal membranes, which prevents analyses using our SMR-based approach, we used microscopy to analyze the plasma membrane specific lipid labeling in freely proliferating (small) and polyploid (large) L1210 cells (Fig. 5G). More specifically, we analyzed plasma membrane labeling intensity and normalized the results to reflect the total plasma membrane lipid labeling across the whole cell. In these experiments polyploidization increased cell volumes nearly 100-fold and the cells maintained near-spherical shapes. We observed that the L1210 cells scale their plasma membrane lipids nearly isometrically with a scaling factor of ~1.14 (Fig. 5G). Together with our previous findings, these results indicate that both protein and lipid components of the plasma membrane accumulate at an approximately fixed rate as cells grow larger, and that cells do not downregulate their cell surface expansion despite excessive size increases.

Plasma membrane folds enable a constant SA/V ratio as cells grow larger

Our results suggest that plasma membrane ultrastructure must accumulate folding and structural complexity as cells grow larger. To visualize and qualitatively verify this, we carried out scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of L1210 and THP-1 cells with different levels of ploidy. This revealed that L1210 cell plasma membrane folding was radically higher in large polyploid cells in comparison to small diploid cells (Figs. 5H and S5A). While the small diploid L1210 cells displayed large areas of relatively smooth membrane, the large polyploid L1210 cells were uniformly covered in highly folded membrane. Similarly, membrane folding and complexity increased with cell size in THP-1 cells (Fig. S5B). However, the membrane folding in large polyploid THP-1 cells was often polarized to a specific region of the cell and took the form of very large folds rather than small uniform protrusions, as seen in L1210 cells. We also imaged small and large (polyploid) L1210 cells using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This revealed that the plasma membrane of the large polyploid cells adopts microvilli-like structures which were not observed in the small L1210 cells (Fig. 5I). Overall, these results support our conclusion that plasma membrane area scales isometrically with cell size causing membrane folding to increase in larger cells.

DISCUSSION

Different human cell types vary many orders of magnitude in size 58 and all proliferating cells within a cell type vary, at minimum, 2-fold in size. Across all these sizes, cells need to maintain sufficient plasma membrane area to deform, uptake nutrients and interact with their environment. While cell differentiation can alter the SA/V ratio, our results show that during cell growth the SA/V ratio is surprisingly constant. This is consistent with previous studies that have revealed that cell size scaling of most transcripts, proteins and cell organelles is near-isometric 19,27–41. Importantly, our results indicate a near-constant SA/V ratio despite almost a 100-fold cell size increase, and we have previously shown in the same model system that cells can maintain exponential cell growth at these very large cell sizes 53. These results suggest that surface area does not become growth limiting when mammalian cells grow larger. Notably, our work has focused on near-spherical cells where the cell geometry makes the ⅔-geometric size scaling of cell surface area most likely. As we do not observe this, the ⅔-geometric size scaling, which is often considered to limit cell size and growth, is unlikely to reflect the behavior of most mammalian cells.

A long-standing question in cell biology is ‘how do cells sense their size?’ If SA/V ratio decreased with increasing cell size, it could serve as a metric for cells to sense their size 13,18,19. Our results argue that mammalian cells do not use the SA/V ratio for cell size sensing. However, more specific molecular mechanisms could still operate in an analogous manner 54. We have identified specific cell surface proteins that do not follow isometric size scaling making these proteins potential cell size-sensors. Furthermore, proteins that sense plasma membrane curvature, such as I-BAR proteins and tetraspanins 20,59,60, could also act as cell size-sensors, because the constant SA/V ratio requires that the plasma membrane accumulates more folding as cell size increases.

The SA/V ratio also impacts cells’ ability to deform 6. For example, blood and immune cells frequently pass through the microvasculature by squeezing through constrictions, and this is enabled by plasma membrane reservoirs 15,16,61. The constant SA/V ratio may enable immune cells to grow larger, as seen during T and B cell activation 50, while undergoing efficient intravasation independently of their size. Curiously, increases in membrane folding are also observed on larger nuclei 62, suggesting that nuclear deformation could also be size independent. In addition, the size-dependent plasma membrane morphology may result in cell size-dependent mechanosensing, endocytosis and exocytosis, all of which can be impacted by local membrane geometry and/or tension 20,60,63–66.

More broadly, the constant SA/V ratio can simplify surface area regulation. Cell division increases the apparent cell surface area. Should the SA/V ratio decrease as cells grow larger, cells would have to sense how much plasma membrane is needed to facilitate cytokinesis. This is dependent on the cell division size, necessitating either cell size or growth-sensing. In contrast, when the SA/V ratio is maintained constant, there is no need for additional plasma membrane during cytokinesis, and cells do not require cell size or growth sensing to maintain an appropriate cell surface area. This makes cytokinesis robust towards variability in cell division size, while also ensuring that plasma membrane area does not become limiting for any other cell functions due to cell size increases. We propose that the constant SA/V ratio may represent a fundamental cellular design principle that enables cells to robustly grow and operate across a range of cell sizes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, primary cells & cell cycle reporters

L1210 (ATCC, #CCL-219), BaF3 (RIKEN BioResource Center, #RCB4476), OCI-AML3 (gifted by the Chen lab at MIT), THP-1 (gifted by the Chen lab at MIT), FL5.12 (gifted by the Vander Heiden lab at MIT) and S-HeLa (gifted by the Elias lab at Brigham And Women’s Hospital) cells were cultured in RPMI (Invitrogen # 11835030) supplemented with 10% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich), 10mM HEPES, 1mM sodium pyruvate and antibiotic/antimycotic. S-HeLa cell cultures were maintained on ultra-low attachment plates (Sigma-Aldrich, #CLS3471–24EA) to prevent cell adhesion. FL5.12 cells were cultured in the presence of 10 ng/ml IL-3 (R&D Systems). Cell cycle exit in FL5.12 was achieved by washing the cells three times with PBS to remove IL-3 from the cells and by placing the cells in IL-3 free culture media for 48 h. All experiments were carried out when cells are at exponential growth phase at confluency of 200.000–700.000 cells/ml. All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma.

L1210 cells expressing the FUCCI sensor were generated in a previous study 67. Other cell lines were transduced with lentiviral vector carrying geminin-GFP encoding plasmid and puromycin resistance (Cellomics Technology, #PLV-10146–200). Transductions were carried out using spinoculation. Approximately 50.000 cells were mixed with ~2.5*106 virus particles in 400 μl of culture media containing 8 μg/ml polybrene and the mixture was centrifuged for 1 h at 800 g at RT. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in normal culture media and grown o/n. The spinoculation procedure was repeated the next day after which selection was started using 5 μg/ml of puromycin. Following a week of selection, the cells were sorted for GFP positive cells using BD Biosciences FACS Aria and this was followed by a clonal selection in media containing the selection marker. Clones were evaluated for biphasic geminin-GFP expression using flow cytometry. The top clones used for experiments were also examined for the loss of the geminin-GFP reporter signal at mitosis using timelapse microscopy with the IncuCyte live cell analysis imaging system by Sartorius.

Primary human monocytes were isolated from apheresis leukoreduction collars obtained from anonymous healthy platelet donors at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Specimen Bank under an Institutional Review Board–exempt protocol. First, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated using density gradient centrifugation of the collars (Lymphoprep, StemCell Technologies Inc, #07801). Monocytes were then enriched from the PBMC samples via the EasySep Human Monocyte Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies Inc, #19059). Monocytes were seeded at a concentration of 500.000 cells/mL in blood cell growth media (Sigma-Aldrich, #615–250) and cultured in a 24 well ultra-low attachment well plates (Sigma-Aldrich, #CLS3473–24EA) at 37°C for 2 h prior to sample staining and measurements. Each experiment was carried out using monocytes isolated from a different patient.

Scaling control beads

For surface labelled beads, SPHERO Amino Polystyrene beads ranging from 8.0 to 12.9 μm in diameter (Spherotech, #AP-100–10) were labelled with amine labeling as detailed below for cells. For volume labelled beads, we used readily fluorescent (Nile Red) polystyrene beads ranging from 5.0 to 7.9 μm in diameter (Spherotech, #FP-6056–2). The beads were FACS sorted using BD Biosciences FACS Aria, to enrich the population for the small and large beads.

Surface labeling

Amine surface labeling of cells was carried out using LIVE/DEAD Fixable Red Dead Cell Stain kit (Invitrogen, #L23102), as detailed previously 52. Briefly, the cells were washed with ice cold PBS, mixed in ice cold PBS with the amine reactive stain at 5x supplier’s recommended concentration, and stained in dark on ice for 10 minutes. Staining was stopped by mixing the cells with cold FBS containing culture media and by washing the cells with cold PBS. Cells were mixed in PBS at 500.000 cells/ml and immediately analyzed using SMR or microscopy. Thiol surface labeling was carried out as amine labeling, but the stain used was Alexa Fluor 568 C5 Maleimide (Invitrogen, #A20341) at 50 μM concentration. The Alexa Fluor 568 C5 Maleimide stained cells were washed an extra time with cold culture media to remove all stain aggregates.

Plasma membrane lipid labeling was carried out using CellMask Deep Red Plasma membrane stain (Invitrogen, #C10046) with 1:1000 dye dilution in normal culture media. Labeling was done at +4°C for 15 min, after which cells were washed twice with PBS, plated and imaged at RT.

Plasma membrane protein immunolabeling was carried out in normal culture media on ice. First, non-specific Fc receptor binding was blocked using 1:100 dilution of TruStain FcX anti-mouse CD16/32 antibody (BioLegend, RRID:AB_1574975, Cat#101320). 5 min after Fc blocker treatment, antibodies targeting the proteins of interest were added at 1:200 dilution for 15 min. The antibodies used were PE anti-mouse CD19 Antibody (BioLegend, RRID:AB_313643, Cat#115508), APC anti-mouse CD45 Antibody (BioLegend, RRID:AB_2876537, Cat#157606), APC anti-mouse CD54 Antibody (BioLegend, RRID:AB_10612936, Cat#116120) and PE anti-mouse CD98 (4F2) Antibody (BioLegend, RRID:AB_2190813, Cat#128208). For anti-CD98, a APC variant of the same antibody was also used (BioLegend, RRID:AB_2750544, Cat#128211). After immunolabeling, the cells were washed twice with cold culture media and immediately analyzed using SMR or microscopy.

Primary monocyte isolation specificity was validated using CD14 immunolabeling. The cells were incubated with CD14 Monoclonal Antibody (61D3) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (ThermoFisher, eBioscience, RRID:AB_2744748, Cat#53–0149-42) for 20 min at +37°C, and washed twice with PBS. The labelled cells were analyzed using BD Biosciences flow cytometer Celesta with 488 nm excitation laser and 530/30 nm emission filter.

SMR mass and fluorescence measurements

Cell mass measurements were conducted with SMR devices 47,68 coupled to a fluorescence measurement setup 48,50. Fluorescence was measured by an epi-fluorescence setup (Nikon LV-UEPI2), built in conjunction with the SMR system. PMTs (Hamamatsu, #H10722–20) were used to measure the emission intensity in five different bandwidths, 438/24, 515/30, 595/31, 678/70, and 809/81 nm. Geminin-GFP intensity and surface protein labeling intensity were measured in 515/30, and 678/70 respectively. The exact specifications for the illumination source, objective, and emission filters are described in 50. Analog output and voltage modules (National Instruments, #NI-9263, #NI-9215) were used to communicate with PMTs. SMR data were collected at a data rate of ~20 kHz and fluorescence intensity signals from PMTs were collected at a data rate of ~50 kHz.

A custom MATLAB code was used to process the raw SMR and PMT data, as reported previously 50. Fluorescence intensity signals from labeled cells were identified based on positive thresholding, defined by an increase in fluorescence higher than three times the baseline’s standard deviation. Event identification is designed such that if any of the 5 fluorescence channels has a positive event, the intensity of all other channels will be recorded. After independently processing the SMR and PMT data, a custom algorism was used to pair the cell mass and fluorescence signals according to their timestamps 50. Each SMR event was expected to have a matching PMT event, with a short time delay due to the cell travelling between the measurement locations (Fig. S1B). The pairing pipeline computed the time differences between each SMR and PMT event, followed by a manual selection step for a range of acceptable time differences. Data that did not have a single, unique one-to-one match between the SMR and PMT data was excluded.

SMR data gating and scaling factor analysis

Data analysis was conducted using MATLAB. Data from each sample was independently gated and analyzed. The first gating step was done using buoyant mass to remove particles too small to be considered cells. The data was then gated for viable cells using a rectangular gating on amine labeling intensity vs buoyant mass (Fig. S1E). Next, a 2D ellipsoid gating (on amine labeling intensity vs buoyant mass) was performed on the live cell population to remove outliers outside of a 95% confidence interval of the population. To compute the ellipsoid gate, we first calculated the covariance matrix of the amine labeling intensity and buoyant mass values. Eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix were then calculated, and the smallest and largest eigenvalues were determined. These values were then used to determine the semi-major and semi-minor axes of the ellipse. The contour of the ellipse was set around the mean of the dataset, and axe lengths were determined by parameters for a 95% confidence interval using a chi-square value = 2.4777. Data within the ellipsoid gate were then used for the scaling factor analysis.

For cell cycle specific analyses of the scaling factor, we used geminin-GFP vs buoyant mass data to differentiate G1 and S&G2 populations using a quadratic gating design (Fig. 2A). For polyploidy analysis, different cell cycle generations were determined by manual polygon gating on geminin-GFP vs buoyant mass, which was done with MATLAB function drawpolygon().

For sensitivity analysis (Fig. S1G), manual gating on amine labeling vs buoyant mass was done with MATLAB function drawpolygon(). For rectangular gating in the sensitivity analysis, the amine labeling intensity of each cell was first normalized by its buoyant mass and the gating was performed on mass-normalized amine label vs buoyant mass. Bootstrap analysis (Fig. S1F) was conducted with resampling with replacement using MATLAB function randi() on the cell indices from the sample population.

Scaling factor calculations were conducted in MATLAB. The scaling factor was determined by the slope fitting using linear regression function regstats(x, y, ‘linear’) on the log2 transformed data. The fitted slope and r-square values were then recorded. To compute the 95% confidence interval of the slope, coefCI() function was used.

When analyzing how cell cycle transitions influence cell surface amine labeling, we separated cell cycle stages as shown in Fig. 2A, and we identified identically sized cell pairs in different cell cycle stages which were used to compare amine labeling intensity changes between the cell cycle stages. Notably, the separation between G2/M and cytokinetic cells is carried out based on the degradation of geminin-GFP, which separates near-spherical cells (before anaphase onset) from non-spherical cytokinetic cells (after anaphase onset. The data for L1210 cells is adapted from 52. For full details and validations, see 52.

Chemical perturbations

Cell cycle exit in THP-1 cells was achieved by treating the cells with 1 μM CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib (Cayman Chemical, #16273) for 5 days. Palbociclib was kept present during surface amine labeling. Chemically induced polyploidy was achieved by treating L1210 FUCCI cells with 50 nM Barasertib (a.k.a. AZD1152-HQPA; Cayman Chemical, Cat#11602) 53. To obtain cells with varying sizes and cell cycle states, while avoiding cells that are too large for the SMR microchannels, different Barasertib treatment durations (typically 0.25 h, 10 h, 20 h) were pooled together immediately prior to cell surface amine labeling. For polyploid THP-1 FUCCI cells, 100 nM Barasertib was used, and treatment times were 0.25 h, 24 h, and 48 h. Barasertib treatment was maintained throughout the amine labeling and SMR experiments. For microscopy experiments, L1210 cell Barasertib treatment lasted 48 h and THP-1 cell Barasertib treatment lasted 72 h, after which treated and untreated cells were pooled together for sample preparation in the presence of Barasertib.

Cell volume measurements

Single-cell volumes were measured using a coulter counter (Beckman Coulter). In short, cells were immersed in PBS with 1:100 dilution, and 1 ml of the solution was measured on the coulter counter using a 100 μm diameter cuvette. In a typical experiment, we measured >2000 cells and particles below the size of 100 fl were excluded.

Single-cell volumes were also measured jointly with cell buoyant masses using the SMR according to a previously detailed fluid switching approach 46. In short, cell’s buoyant mass was first measured in normal media in the SMR, after which the cell was immersed in high density media that comprised of normal culture media with 35% OptiPrep density gradient medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#D1556). The cell was then flow back through the SMR cantilever to obtain a measurement in high density media. These two buoyant mass measurements were used to calculate the volume of the cell 46, and to correlate cell buoyant mass in normal culture media with cell volume.

Cell cycle analyses

Cell cycle perturbations were validated using flow cytometry-based detection of DNA content and geminin-GFP levels. Following treatment, cells were washed with PBS and fixed by mixing with ice cold 70% EtOH and incubating o/n. The cells were then washed with PBS and labelled with FxCycle PI/RNase Staining Solution (Invitrogen, #F10797) for 30 min in dark at RT. The cells were analyzed using BD Biosciences flow cytometer LSR II with 488 nm and 561 nm excitation lasers and 515/20 nm and 610/20 nm emission filters.

Light microscopy and image analysis

All microscopy samples were plated on poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, #P8920) coated glass bottom CELLVIEW dishes (Greiner Bio-One, #627975) and imaged at RT using DeltaVision wide-field deconvolution microscope. Imaging was done using standard FITC, PE, Alexa594 and APC filters, a 100x oil-immersion objective and oil with refractive index of 1.516 (Cargille Laboratories). For cell surface amine labeling, z-layers were collected with 0.2 μm spacing covering typically a 4 μm height at the middle of the cell. For cell surface protein immunolabeling, z-layers were collected with 0.25 μm spacing covering typically a 10 μm in height. For plasma membrane lipid labeling, z-layers were collected with 1 μm spacing covering typically 12 μm height at the middle of the cells. Image deconvolution was carried out using SoftWoRx 7.0.0 software. For cell surface protein and antibody labeling approaches, images were processed using ImageJ (version 1.53q).

For plasma membrane lipid labeling, we developed a MATLAB-based image analysis approach. In short, cells are automatically detected, the z-layer at the middle of each cell is manually selected, and then line profiles are drawn starting from the center of the cell and ending outside of the plasma membrane. Line profiles that are impacted by neighboring cells are automatically excluded from the analysis. The line profiles from each cell were averaged, aligned to the plasma membrane and used to quantify the total intensity of plasma membrane signal (area under the curve (AUC) in the line profiles). We then established how the one-dimensional AUC quantifications compare to the total plasma membrane content in the cell. To achieve this, we assumed a spherical cell with a membrane volume that can be defined as:

where depicts cells outer radius, depicts cells inner radius (to the inner side of the plasma membrane), is a constant, and is the scaling factor. The ‘thickness’ of the plasma membrane corresponds to the AUC of the line profiles. Assuming that , we can solve for and obtain

where depicts a constant. We therefore cubed the quantified line profile AUC values so that isometric size scaling of total plasma membrane corresponds to a scaling factor of 1. For cell size quantifications, we quantified the cell radius from the line profiles and calculated the total cell volume assuming a spherical cell shape.

Electron microscopy

For SEM, L1210 FUCCI and THP-1 FUCCI cells were treated with Barasertib for 48 h and 72, respectively, at a cell concentration of ~300.000 cells/ml to induce polyploidy. The polyploid cells and diploid control cells were then mixed in media containing Barasertib and placed on a round cover slip coated with poly-L-lysine. The cells were given 15 min to adhere, and the media switched to PBS. The cells were then fixed with glutaraldehyde and paraformaldehyde at 2.5% and 2% final concentration, respectively, in PBS for 30 min at RT. After fixation, the cells were washed with PBS and twice with 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer at 4 °C. Secondary fixation was carried out with 1% osmium tetroxide in the sodium cacodylate buffer for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were then washed with DI water four times and moved to stepwise dehydration with that was carried out using ethanol (EtOH) at RT. Each step lasted 5 min and the EtOH concentrations were 35%, 45%, 50%, 65%, 70%, 85%, 95% and 100%. Next the cells were treated for 15 min with 50% EtOH and 50% tetramethyl silane (TMS), then 15 min with 20% EtOH and 80% TMS, and finally twice for 5 min with 100% TMS. The TMS was removed, and the cells were left to dry at RT o/n. Dried SEM samples were sputter coated with gold for 120 s. Imaging was carried out using Zeiss Crossbeam 540 scanning electron microscope at the Peterson (1957) Nanotechnology Materials Core Facility at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. Typical imaging was carried out with 5 kV accelerating voltage, 500 pA probe current, a working distance of 8 mm, and a magnification of 4000x. Typical image resolution was 5 nm/pixel.

For TEM, the cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with glutaraldehyde and paraformaldehyde at 2.5% and 2% final concentration, respectively, in PBS for 60 min at +4°C. Following fixation, the cells were washed three times with 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer at 4 °C. Secondary fixation was carried out for 60 min on ice with 1% osmium tetroxide in a solution containing 1.25% potassium ferrocyanide and 100 mM sodium cacodylate. The samples were then washed three times with 100 mM sodium cacodylate and three times with 50 mM sodium maleate at pH 5.2. The samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate in sodium maleate buffer o/n at RT. The next day, the samples were rinsed twice with distilled H2O, and dehydrated with ethanol using 10 min incubations at following EtOH concentrations: 30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, 100%, and again 100%. The samples were incubated in propylene oxide for 30 min, twice, and moved to propylene oxide - resin mixture (1:1) for o/n at RT. The following day, the samples were moved to a new propylene oxide - resin mixture (1:2) for 6 hours at RT, and then into full resin o/n at RT. The resin infiltrated samples were moved to molds and polymerized at 60°C for 48 hours. The polymerized resin embedded samples were then sectioned into 60 nm thin slices using a Leica UC7 ultramicrotome and collected on carbon-coated nitrocellulose film copper grids. Imaging was carried out using FEI Tecnai T12 transmission electron microscope at the Peterson (1957) Nanotechnology Materials Core Facility at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research. Typical imaging was carried out with 120 kV voltage, and a magnification of 4800x, resulting in an image resolution of 3.8 nm/pixel. Images were captured with an AMT XR16 CCD camera.

Gene expression data analysis

All gene expression data were obtained from a previous publication 43, where SMR-based cell mass and mass accumulation rate measurements were coupled to single-cell collection and Smart-Seq2-based scRNA-seq. The transcriptomic data represents normalized mRNA count measurements (transcripts per million). As mRNA levels scale isometrically with cell volume, this normalization was considered to reflect mRNA concentrations in each cell. The mRNA concentrations were converted to a proxy of absolute mRNA levels using each cell’s volume, which was obtained from the buoyant mass measurement, assuming a cell density of 1.05 g/ml. These data were then filtered according to the following criteria: 1) Cells with negative mass accumulation rate (i.e. dying cells) were excluded, 2) only cells within normal size range (30–100 pg) were included, 3) genes that were expressed/detected in less than 30 L1210 cells or in less than 90 FL5.12 cells were excluded, and 4) cells were excluded when most abundant transcripts (across all data) were not detected. The remaining dataset consisted of 7994 different mRNAs in 88 L1210 cells and of 8035 different mRNAs in 203 FL5.12 cells. Log-converted mRNA data were then correlated with the log-converted buoyant mass of each cell, and the scaling factor (slope of the correlation) was used to evaluate size scaling. The grouping of genes was done according to GO-terms retrieved from the Mouse Genome Database (MGD), Mouse Genome Informatics, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine (http://www.informatics.jax.org, retrieved May, 2022) 69. The GO-terms examined were External side of plasma membrane (GO:0009897), and Cell division (GO:0051301).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

SRM and TPM received funding from NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM150901). SRM also received funding from the MIT Center for Cancer Precision Medicine and Virginia and DK Ludwig Fund for Cancer Research. The work was supported by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute, and we thank the Koch Institute’s Robert A. Swanson (1969) Biotechnology Center for technical support, specifically the Peterson (1957) Nanotechnology Materials Core Facility (RRID:SCR_018674) and the Microscopy Core Facility. We also thank Prof. J. Chen and Dr. N. Ivica for providing the wt OCI-AML3 and THP-1 cells, Dr. L. Debaize fron Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for assisting with primary patient samples, and Michael Collis from Spherotech for providing volume-labeled beads.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

S.R.M. is a co-founder of Travera and Affinity Biosensors, which develop technologies relevant to the research presented in this work. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplemental information

Supplemental information contains Figures S1–S5 and Dataset S1.

Data and code availability

Single-cell buoyant mass and fluorescent labeling data are available in the supplementary section (Dataset S1). Image analysis code is available at https://github.com/alicerlam/lam-miettinen-surface-area-to-volume-scaling.

REFERENCES

- 1.Glazier D. S. Beyond the ‘3/4-power law’: variation in the intra- and interspecific scaling of metabolic rate in animals. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 80, 611–662 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miettinen T. P., Caldez M. J., Kaldis P. & Bjorklund M. Cell size control - a mechanism for maintaining fitness and function. Bioessays 39, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okie J. G. General models for the spectra of surface area scaling strategies of cells and organisms: fractality, geometric dissimilitude, and internalization. Am Nat 181, 421–439 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young K. D. The selective value of bacterial shape. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 70, 660–703 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris C. E. & Homann U. Cell surface area regulation and membrane tension. Journal of Membrane Biology 179, 79–102 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figard L. & Sokac A. M. A membrane reservoir at the cell surface. Bioarchitecture 4, 39–46 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall W. F. et al. What determines cell size? BMC Biol 10, 1–22 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niklas K. J. A Phyletic Perspective on Cell Growth. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7, a019158 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reber S. & Goehring N. W. Intracellular Scaling Mechanisms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7, a019067 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojkic N., Serbanescu D. & Banerjee S. Surface-to-volume scaling and aspect ratio preservation in rod-shaped bacteria. Elife 8, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi H. et al. Precise regulation of the relative rates of surface area and volume synthesis in bacterial cells growing in dynamic environments. Nat Commun 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oldewurtel E. R., Kitahara Y. & van Teeffelen S. Robust surface-to-mass coupling and turgor-dependent cell width determine bacterial dry-mass density. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, e2021416118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris L. K. & Theriot J. A. Relative Rates of Surface and Volume Synthesis Set Bacterial Cell Size. Cell 165, 1479–1492 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walton K. D., Freddo A. M., Wang S. & Gumucio D. L. Generation of intestinal surface: an absorbing tale. Development 143, 2261–2272 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guillou L. et al. T-lymphocyte passive deformation is controlled by unfolding of membrane surface reservoirs. Mol Biol Cell 27, 3574–3582 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid-Schonbein G. W., Shih Y. Y. & Chien S. Morphometry of Human Leukocytes. Blood 56, 866–875 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dill K. A., Ghosh K. & Schmit J. D. Physical limits of cells and proteomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 17876–17882 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brownlee C. & Heald R. Importin alpha Partitioning to the Plasma Membrane Regulates Intracellular Scaling. Cell 176, 805–815 e8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miettinen T. P. et al. Identification of transcriptional and metabolic programs related to mammalian cell size. Current Biology 24, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadart C., Venkova L., Recho P., Lagomarsino M. C. & Piel M. The physics of cell-size regulation across timescales. Nat Phys 15, 993–1004 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blank H. M. et al. Translational control of lipogenic enzymes in the cell cycle of synchronous, growing yeast cells. EMBO Journal 36, 487–502 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stumpf C. R., Moreno M. V, Olshen A. B., Taylor B. S. & Ruggero D. The translational landscape of the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell 52, 574–582 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanenbaum M. E., Stern-Ginossar N., Weissman J. S. & Vale R. D. Regulation of mRNA translation during mitosis. Elife 4, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atilla-Gokcumen G. E. et al. Dividing cells regulate their lipid composition and localization. Cell 156, 428–439 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Alvarez M., Zhang Q., Finger F., Wakelam M. J. & Bakal C. Cell cycle progression is an essential regulatory component of phospholipid metabolism and membrane homeostasis. Open Biol 5, 150093 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scaglia N., Tyekucheva S., Zadra G., Photopoulos C. & Loda M. De novo fatty acid synthesis at the mitotic exit is required to complete cellular division. Cell Cycle 13, 859–868 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng L. et al. Size-scaling promotes senescence-like changes in proteome and organelle content. bioRxiv (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.08.05.455193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorgensen P. et al. The size of the nucleus increases as yeast cells grow. Mol Biol Cell 18, 3523–3532 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanz M. C. et al. Increasing cell size remodels the proteome and promotes senescence. Mol Cell 82, 3255–3269.e8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marguerat S. et al. Quantitative analysis of fission yeast transcriptomes and proteomes in proliferating and quiescent cells. Cell 151, 671–683 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miettinen T. P. & Björklund M. Cellular Allometry of Mitochondrial Functionality Establishes the Optimal Cell Size. Dev Cell 39, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padovan-Merhar O. et al. Single mammalian cells compensate for differences in cellular volume and DNA copy number through independent global transcriptional mechanisms. Mol Cell 58, 339–352 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhurinsky J. et al. A coordinated global control over cellular transcription. Current Biology 20, 2010–2015 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viana M. P. et al. Integrated intracellular organization and its variations in human iPS cells. Nature 613, 345–354 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y., Zhao G., Zahumensky J., Honey S. & Futcher B. Differential Scaling of Gene Expression with Cell Size May Explain Size Control in Budding Yeast. Mol Cell 78, 359–370 e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin J. & Amir A. Homeostasis of protein and mRNA concentrations in growing cells. Nature Communications 2018 9:1 9, 1–11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun X. M. et al. Size-Dependent Increase in RNA Polymerase II Initiation Rates Mediates Gene Expression Scaling with Cell Size. Current Biology 30, 1217–1230.e7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basier C. & Nurse P. The cell cycle and cell size influence the rates of global cellular translation and transcription in fission yeast. EMBO J 42, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swaffer M. P. et al. RNA polymerase II dynamics and mRNA stability feedback scale mRNA amounts with cell size. Cell 186, 5254–5268.e26 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cadart C. & Heald R. Scaling of biosynthesis and metabolism with cell size. Mol Biol Cell 33, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rafelski S. M. et al. Mitochondrial network size scaling in budding yeast. Science 338, 822–824 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sokac A. M. Seeing a Coastline Paradox in Membrane Reservoirs. Dev Cell 43, 541–542 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimmerling R. J. et al. Linking single-cell measurements of mass, growth rate, and gene expression. Genome Biol 19, 207 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thul P. J. et al. A subcellular map of the human proteome. Science 356, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper G. M. The Cell : A Molecular Approach. (ASM Press ; Sinauer Associates, Washington, D.C. Sunderland, Mass., 2000). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kang J. H. et al. Noninvasive monitoring of single-cell mechanics by acoustic scattering. Nat Methods 16, 263–269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burg T. P. et al. Weighing of biomolecules, single cells and single nanoparticles in fluid. Nature 446, 1066–1069 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang J. H. et al. Monitoring and modeling of lymphocytic leukemia cell bioenergetics reveals decreased ATP synthesis during cell division. Nat Commun 11, 4983 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miettinen T. P. et al. Direct quantification of sinking velocities across unicellular algae. bioRxiv (2023) doi: 10.1101/2023.06.20.545838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu W. et al. Measuring single-cell density with high throughput enables dynamic profiling of immune cell and drug response from patient samples. bioRxiv (2024) doi: 10.1101/2024.04.25.591092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miettinen T. P., Ly K. S., Lam A. & Manalis S. R. Single-cell monitoring of dry mass and dry mass density reveals exocytosis of cellular dry contents in mitosis. Elife 11, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alonso-Matilla R., Lam A. & Miettinen T. P. Cell intrinsic mechanical regulation of plasma membrane accumulation in the cytokinetic furrow. bioRxiv (2023) doi: 10.1101/2023.11.13.566882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mu L. et al. Mass measurements during lymphocytic leukemia cell polyploidization decouple cell cycle- and cell size-dependent growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 15659–15665 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hubatsch L. et al. A cell-size threshold limits cell polarity and asymmetric division potential. Nat Phys 15, 1078–1085 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carpen O., Pallai P., Staunton D. E. & Springer T. A. Association of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) with actin-containing cytoskeleton and alpha-actinin. Journal of Cell Biology 118, 1223–1234 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hecht V. C. et al. Biophysical changes reduce energetic demand in growth factor–deprived lymphocytes. Journal of Cell Biology 212, 439–447 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neurohr G. E. et al. Excessive Cell Growth Causes Cytoplasm Dilution And Contributes to Senescence. Cell 176, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hatton I. A. et al. The human cell count and size distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120, e2303077120 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dharan R. et al. Transmembrane proteins tetraspanin 4 and CD9 sense membrane curvature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119, e2208993119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quiroga X. et al. A mechanosensing mechanism controls plasma membrane shape homeostasis at the nanoscale. Elife 12, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Namvar A. et al. Surface area-to-volume ratio, not cellular viscoelasticity, is the major determinant of red blood cell traversal through small channels. Cell Microbiol 23, e13270 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson J. A. et al. Scaling behaviour and control of nuclear wrinkling. Nat Phys 19, 1927–1935 (2023). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shi Z., Graber Z. T., Baumgart T., Stone H. A. & Cohen A. E. Cell Membranes Resist Flow. Cell 175, 1769–1779.e13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gauthier N. C., Fardin M. A., Roca-Cusachs P. & Sheetz M. P. Temporary increase in plasma membrane tension coordinates the activation of exocytosis and contraction during cell spreading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 14467–14472 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang G. & Galli T. Reciprocal link between cell biomechanics and exocytosis. Traffic 19, 741–749 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kozlov M. M. & Chernomordik L. V. Membrane tension and membrane fusion. Curr Opin Struct Biol 33, 61–67 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Son S. et al. Direct observation of mammalian cell growth and size regulation. Nat Methods 9, 910–912 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kang J. H. et al. Noninvasive monitoring of single-cell mechanics by acoustic scattering. Nat Methods 16, 263–269 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bult C. J. et al. Mouse Genome Database (MGD) 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D801–D806 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.