Abstract

Objective:

Kisspeptin, encoded by the Kiss1 gene, ties puberty and fertility to energy status; however, the metabolic factors that control Kiss1-expressing cells need to be clarified.

Methods:

To evaluate the impact of IGF-1 on the metabolic and reproductive functions of kisspeptin producing cells, we created mice with IGF-1 receptor deletion driven by the Kiss1 promoter (IGF1RKiss1 mice). Previous studies have shown IGF-1 and insulin can bind to each other’s receptor, permitting IGF-1 signaling in the absence of IGF1R. Therefore, we also generated mice with simultaneous deletion of the IGF1R and insulin receptor (IR) in Kiss1-expressing cells (IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice).

Results:

Loss of IGF1R in Kiss1 cells caused stunted body length. In addition, female IGF1RKiss1 mice displayed lower body weight and food intake plus higher energy expenditure and physical activity. This phenotype was linked to higher proopiomelanocortin (POMC) expression and heightened brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis. Male IGF1RKiss1 mice had mild changes in metabolic functions. Moreover, IGF1RKiss1 mice of both sexes experienced delayed puberty. Notably, male IGF1RKiss1 mice had impaired adulthood fertility accompanied by lower gonadotropin and testosterone levels. Thus, IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells impacts metabolism and reproduction in a sex-specific manner. IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had higher fat mass and glucose intolerance, suggesting IGF1R and IR in Kiss1-expressing cells together regulate body composition and glucose homeostasis.

Conclusions:

Overall, our study shows that IGF1R and IR in Kiss1 have cooperative roles in body length, metabolism, and reproduction.

Keywords: IGF-1 receptor, Insulin receptor, Kiss1-expressing cells, Body weight, Reproduction

1. INTRODUCTION

Kisspeptin (encoded by the Kiss1 gene) is a critical regulator of both puberty onset and fertility in mammals with expression throughout the reproductive axis [1–3]. In the brain, kisspeptin exerts its effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis by stimulating gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neuron activity [4; 5]. Reproduction requires adequate energy stores [6]. Kiss1-expressing neurons have been previously hypothesized to serve as a primary transmitter of metabolic signals from the periphery to GnRH neurons [6–11]. Studies have documented a clear impact of nutrition or metabolic stress on Kiss1 expression in the hypothalamus [9; 12–14]. For example, fasting mice displayed reduced hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA levels, which preceded a decline in GnRH expression [12]. Chronic subnutrition during puberty reduced Kiss1 mRNA levels in female rats [14]. Furthermore, repeated central injections of kisspeptin restored pubertal progression to female rats subjected to chronic subnutrition [14]. Thus, Kiss1-expressing neurons can coordinate reproduction with metabolic status.

Kiss1-expressing neurons in mice are mainly located in two regions of the hypothalamus, one in the arcuate nucleus of hypothalamus (ARH) and the other in the rostral periventricular area of the third ventricle (RP3V) [15–17]. Recently, Kiss1-expressing neurons of the ARH have been shown to be involved in diet-induced obesity in several animal models [18–20]. Female mice with deletion of the receptor for the gut peptide ghrelin in Kiss1-expressing cells were resistant to body weight gain on a high fat diet (HFD) [18]. In addition, lack of the endoplasmic reticulum calcium-sensing protein stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) in Kiss1 neurons of the ARH protected ovariectomized female mice from developing obesity and glucose intolerance with HFD. The mechanisms underlying how Kiss1-expressing cells regulate metabolism are beginning to be uncovered. Optogenetic activation of ARH Kiss1 neurons evokes glutamatergic excitatory postsynaptic currents in arcuate proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and agouti-related peptide/neuropeptide Y (AgRP/NPY) neurons. Conversely, these neurons affect Kiss1 neuron activity. NPY can suppresses firing of ARH Kiss1 neurons kisspeptin neurons in both sexes [21], and stimulation of AgRP fibers causes a direct inhibition of Kiss1 neurons in the ARH and AVPV in mice [22]. Kiss1 neurons appear to mediate the stimulatory effects of the POMC product α-MSH on luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion [23].

These functional connections likely allow Kiss1 neurons to coordinate reproduction and energy balance [24; 25].

Kiss1-expressing neurons respond to circulating metabolic cues. Some evidence suggests that leptin acts via Kiss1-expressing cells to exert its effects on fertility [26], although deletion of leptin receptor from Kiss1-expressing cells did not change puberty or fertility in mice of both sexes [27]. Insulin is another circulating factor that may influence Kiss1-expressing neurons [28; 29]. Only 5% of Kiss1-expressing neurons in all hypothalamic sites express IR protein or activated downstream signaling pathways in response to insulin [28–30]. On the other hand, IR mRNA co-expression was nearly 22% in the ARH [29]. We and others have reported a delay in the initiation of puberty in both sexes [29] or an alteration in the regulation of fasting glucose levels in male mice [30] as a result of loss of the IR in Kiss1-expressing cells. However, insulin sensing by Kiss1-expressing cells is not required for adult fertility, body growth or energy balance [29]. To explore whether insulin and leptin signaling interact, we have previously ablated both leptin and insulin signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells [31]. We found that the addition of leptin insensitivity did not alter the reproductive phenotype of mice with single deletion of IR; thus, Kiss1 neurons do not directly mediate the critical role that insulin and leptin play in reproduction [31]. These studies suggest that Kiss1-expressing cells respond to other metabolic cues. Notably, IGF-1 and insulin act through related tyrosine kinase receptors whose signals converge on IR substrate proteins [32] and activate phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to promote AKT signaling [33]. IGF1R and IR signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells may therefore jointly regulate puberty, fertility, and metabolic functions, potentially suggesting that the effects of loss of IR signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells may be compensated by the existence of IGF1R signaling.

IGF1R signaling plays a critical role in the regulation of several important physiological functions [34–37]. Over-expression central IGF-1 or intracerebroventricular injection of IGF-1, increases appetite, improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, and elevates UCP1 expression in BAT [34]. In addition, IGF-1 acts centrally to mediate many of its effects on reproduction [35; 36]. Notably, brain IGF1R knockout mice suffered from growth retardation, infertility, and abnormal behavior [37], while deletion of IGF1R in GnRH neurons did not impact fertility [38]. Thus, Kiss1-expressing neurons may mediate central IGF1R’s reproductive effects. In addition, it is currently unclear whether Kiss1-expressing cells in the periphery mediate the effects of IGF1 on fertility and energy use. To begin to answer these questions, we characterized the metabolic and reproductive functions of mice lacking only IGF1R (IGF1RKiss1 mice) or both IGF1R and IR specifically in Kiss1-expressing cells (IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals and genotyping

To generate mice with the IGF1R specifically deleted in Kiss1-expressing cells, Kiss-cre mice [39] (RRID:IMSR_JAX:023426) were crossed with IGF1R-floxed mice (RRID:IMSR_JAX:016831) and bred to homozygosity for the floxed allele. The IGF1Rloxp/loxp mice were designed with loxP sites flanking exon 4. Excision of exon 4 in the presence of Cre recombinase results in a truncated protein that has no functional capacities [40]. Littermates carrying only loxP sites were used as controls. To generate IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice, Kiss-cre mice were crossed with IGF1R-floxed and IR floxed mice [41] (RRID:IMSR_JAX:006955) and bred to homozygosity for the floxed alleles. All mice were on a C57BL/6 background. Where specified, the mice also carried the Gt(ROSA)26Sor locus-inserted enhanced green fluorescent protein gene [B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm2Sho/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine], as a reporter expressed under the control of Cre recombinase.

Mice were housed in the University of Toledo College of Medicine animal facility at 22°C to 24°C on a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle. They were fed standard rodent chow (2016 Teklad Global 16% Protein Rodent Diet, 12% fat by calories; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, Indiana). On postnatal day (PND) 21, mice were weaned. At the end of the study, all animals were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. Mice were genotyped using the primer pairs described in Table 1. We performed PCR amplification of the IGF-1 receptor floxed (flanked by loxP sites) genomic regions and Cre transgene in tail-derived DNA (Denville DirectAmp™ Genomic DNA Amplication Kit). Additional amplification of the IR floxed genomic regions was performed by Transnetyx, Inc (Cordova, Tennessee) using a real-time PCR-based approach. The University of Toledo College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures.

Table 1.

Mouse primers for measurement of gene expression.

| Primer | Sequence 5’−3’ |

|---|---|

| IGF1R forward | CTTCCCAGCTTGCTACTCTAGG |

| IGF1R reverse | CAGGCTTGCAATGAGACATGGG |

| IGF1R delta | TGAGACGTAGCGAGATTGCTGTA |

| IGF1R p1 | TTATGCCTCCTCTCTTCATC |

| IGF1R p2 | CTTCAGCTTTGCAGGTGCACG |

| IGF1R p3 | ATGACCCAGGGGAGGCTGTGTA |

| IR forward | TGCACCCCATGTCTGGGACCC |

| IR reverse | GCCTCCTGAATAGCTGAGACC |

| IR delta | TCTATCATGTGATCAATGATTC |

| IR p1 | CTGTTCGGAACCTGATGAC |

| IR p2 | TCTATCATGTGATCAATGATTC |

| IR p3 | ATACCAGAGCATAGGAG |

| Kiss1 forward | AGCTGCTGCTTCTCCTCTGT |

| Kiss1 reverse | GCATACCGCGATTCCTTTT |

| POMC forward | GAGGCCACTGAACATCTTTGTC |

| POMC reverse | GCAGAGGCAAACAAGATTGG |

| NPY forward | TAGGTAACAAACGAATGGGG |

| NPY reverse | ATGATGAGATGAGATGTGGG |

| AgRP forward | AGGGCATCAGAAGGCCTGACCA |

| AgRP reverse | CTTGAAGAAGCGGCAGTAGCAC |

| UCP1 forward | GGATGGTGAACCCGACAACT |

| UCP1 reverse | AACTCCGGCTGAGAAGATCTTG |

| ADRB3 forward | TCGACATGTTCCTCCACCAA |

| ADRB3 reverse | GATGGTCCAAGATGGTGCTT |

| Cidea forward | AGGGAGGGACCTTAGGGAAT |

| Cidea reverse | CCAAGTCCAGCTTGGTGAAT |

| PRDM16 forward | CCTAACTTTCCCCACTCCCTCTA |

| PRDM16 reverse | GCTCAGCCTTGACCAGCAA |

| PPARγ forward | AGCCGTGACCACTGACAACGAG |

| PPARγ reverse | GCTGCATGGTTCTGAGTGCTAAG |

2.2. Puberty and reproductive phenotype assessment

Timing of pubertal development was checked daily after weaning by determining vaginal opening (VO) in female mice or balanopreputial separation (BPS) in male mice. Cycle stages were assessed from cytology observed in saline vaginal lavages collected from females approximately 6 to 10-weeks old. The vaginal lavages evaluation was as described previously [42; 43]. First estrus age was defined as the first appearance of two consecutive days with keratinized cells after two previous days with leukocytes [42]. At 3 to 4 months of age, we examined adult fertility in female mice, who were paired with fertile adult male wild-type breeders for eight nights to determine pregnancy rate, interval from mating to birth, and litter size.

Balanopreputial separation (BPS) was checked daily from weaning by manually retracting the prepuce with gentle pressure [29]. After 3 to 4 months of age, each male mouse was paired with one fertile wild-type female for 8 nights. The paired mice were then separated, and pregnancy rate, litter size, and interval from mating to birth were recorded.

2.3. Tissue collection and histology

Ovaries, testes, visceral white adipose tissue (WAT) and BAT were collected and fixed immediately in 10% formalin overnight and then transferred to 70% ethanol. Tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into 5- to 8-μm sections. Sections were stained by hematoxylin and eosin and then analyzed. For follicle and sperm quantification, a minimum of four ovaries and testes for each genotype at 5-month-old age were collected. Follicles were classified into the following categories: primordial, primary, secondary, Graafian. Testes sections were analyzed by evaluating sperm stages, including counting the number of spermatogonium, spermatocytes, spermatid, and spermatozoa using light microscopy under 20x magnification [44]. Sperm counts are reported per seminiferous tubule cross-section.

2.4. Quantitative real-time PCR

Hypothalamus and BAT were removed after the control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice were sacrificed. Total hypothalamic and BAT RNA was extracted from dissected tissues using a RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, California). BAT RNA was extracted by using TRIzol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as described previously [45]. Single-strand cDNA was synthesized with a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) using random hexamers as primers (Appendix A). Each sample was analyzed in duplicate to measure gene expression level. A 25μM cDNA template was used in a 25μl system in 96-well plates with SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix/ROX (Smart Bioscience Inc, Maumee, Ohio). The reactions were run in an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Alternatively, a 10μMcDNA template was used in a 10 μl system in 384-well plates with SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix/ROX (Smart Bioscience Inc, Maumee, Ohio). These reactions were run in a ThermoFisher QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). All data were analyzed using the comparative Ct method (2−ΔΔCt) with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the housekeeping gene. GAPDH Ct values were statistically similar between groups. Relative gene copy number was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt and presented as fold change of the relative mRNA expression of the control group.

2.5. Hormone assays

Submandibular blood was collected from 3- to 4-week-old mice (before VO or balanopreputial separation) and 3-month-old male and female mice on diestrus at 9:00 to 11:00 AM to detect LH, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and estradiol levels. LH and FSH were measured via RIA performed by the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core (Charlottesville, VA). The assay for LH had a detection sensitivity of 3.28 pg/ml, and its intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variance (CVs) were 4.0% and 8.6%. The detection limit of FSH assay was 7.62 pg/ml, while its intra-assay and inter-assay CVs were 7.4% and 9.1%. Serum estradiol was measured by ELISA (Calbiotech, Spring Valley, California) with a sensitivity of 3 pg/mL and intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of <10%. Testosterone in serum was measured by ELISA (Calbiotech, Spring Valley, California) with a sensitivity of 0.1 ng/mL and intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of <10%. Serum IGF-1 was measured by ELISA (Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL) with sensitivity of 0.5 to 18 ng/mL and precision intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of <10%. Serum insulin was measured by ELISA (ALPCO Diagnostics, Salem, NH) with a sensitivity of 3.0- to 200 μIU/mL and precision intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of <10%. Serum C-peptide was measured by ELISA (Crystal Chem, Elk Grove Village, IL) with sensitivity of 0.37 to 15 ng/mL and precision intra-assay and inter-assay CVs of <10%.

2.6. Perfusion and immunohistochemistry

3 to 6-month-old adult male mice and female mice in diestrus were deeply anesthetized by ketamine and xylazine. After brief perfusion with a saline rinse, mice were perfused transcardially with 10% formalin for 10 minutes, and the brain was removed. The brain was post-fixed in 10% formalin at 4°C overnight and immersed in 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose at 4°C for 24 hours each. Then, 30-μm sections were cut by a sliding microtome into five equal serial sections. After rinsing in PBS, sections were blocked for 2 hours in PBS-T (PBS, Triton X-100, and 10% normal horse serum). Then, samples were incubated for 48 hours at 4°C in PBS-T-containing rabbit anti-IGF1R β antibody (1:1000; Cell signaling, Cat#9750), which has been previously validated [46]. After three washes in PBS, sections were incubated in PBS-T (Triton X-100 and 10% horse serum) containing secondary antibodies for 2 hours at room temperature. Secondary antibody was Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1,000, Thermofisher Scientific, Cat. #A-21206). Finally, sections were washed, mounted on slides, cleared, and coverslipped with fluorescence mounting medium containing DAPI (Vectasheild, Vector laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, California). Neurons were quantified in two rostrocaudal levels of the ARH (relative to bregma −1.70 and −1.94 mm). Bregma was determined according to the Allen Brain Atlas (http://mouse.brain-map.org). The quantification was performed on one side of a representative rostrocaudal level of each area analyzed.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Normality testing was used to determine the normal distribution of data. If the data followed a normal distribution, One-way ANOVA was used as the main statistical method to compare the three groups, followed by the Tukey multiple comparison test. If the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. For body weight, body length, energy expenditure, locomotor activity, glucose tolerance test (GTT), and insulin tolerance test (ITT), a two-way ANOVA was used to compare changes over time between three groups. Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were then performed to compare differences among groups. A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Disruption of IGF1R in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IR Kiss1 mice

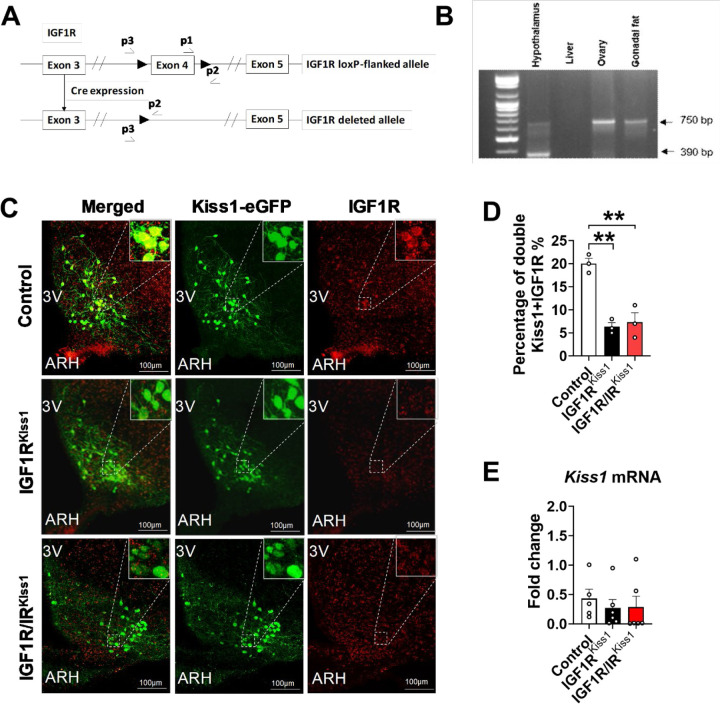

To verify gene excision in Kiss1-expressing cells, PCR was performed on DNA from different tissues. Using this Kiss-cre line crossed with IRloxp mice, our lab has previously shown excision of the floxed portion of the insulin receptor gene in the hypothalamus, as well as in the gonads, liver, and pancreas, with no ablation in the heart, gonadal fat, spleen, or muscle [29]. A 390-bp band showing IGF1R gene deletion was produced from hypothalamic tissue but appeared to be absent from ovary, liver, and fat (Figure 1A and B). To examine IGF1R expression in Kiss1-expressing cells in the hypothalamus, we performed double label immunohistochemistry using antibodies specific for GFP and IGF1R in Kiss1-cre mice crossed with a GFP reporter mouse line (Figure 1C). Approximately 20% of GFP labeled Kiss1 cells in the ARH expressed IGF1R protein, while no double labeling was seen in the RP3V. Compared to control mice, colocalization was sharply lower in IGF1RKiss1 mice (Figure 1D). No changes were seen in hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA expression among all groups (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Loss of hypothalamic IGF1R and IR protein expression in Kiss1 neurons of IGF1RKiss1 mice.

(A) The IGF1R gene with exon 4 flanked by loxP sites (large arrows) before (top panel) and after (bottom panel) Cre recombination. Primers used for detection of the truncated IGF1R gene are labeled p1, p2, and p3. (B) PCR analysis of DNA from hypothalamus, liver, ovary, and testis of a IGF1RKiss1 mouse. The excised IGF1R gene appears as a 390-bp band and the unexercised IGF1R gene sequence as a 750-bp band. (C) Colocation of Kiss1 neuron and IGF1Rs from control and IGF1RKiss1 mice. (D) Quantification of colocalization. (E) Kiss1 mRNA expression in hypothalamus. Values throughout figure are means ±SEM. For entire figure, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA.

3.2. Body growth in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice

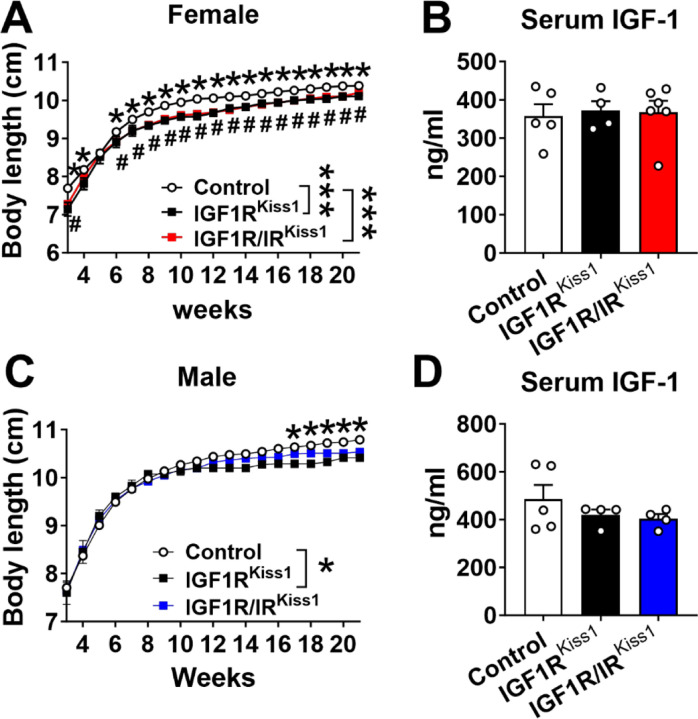

Female IGF1RKiss1 mice showed stunted body length growth starting from the age of weaning (Figure 2A) compared to controls. Female IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had a growth trajectory similar to the single knockout line, but neither exhibited a change in serum IGF-1 level compared to controls (Figure 2B). Male IGF1RKiss1 mice exhibited reduced body length at older ages compared to controls (starting at 4 months of age), with a similar trend in the double knockout (Figure 2C). Again, no difference was seen in circulating IGF-1 levels (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Body length and IGF-1 levels in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 Mice.

(A) Body length curves and (B) serum IGF-1 levels in female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (C) Body length curves and (D) serum IGF-1 levels in male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values. For the entire figure, *p < 0.05 (control vs IGF1RKiss1 or IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice), #p < 0.05 (control vs. IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice), as determined by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test following two-way ANOVA for each time point in A and C, or Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA for B and D.

3.3. Altered energy balance in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice

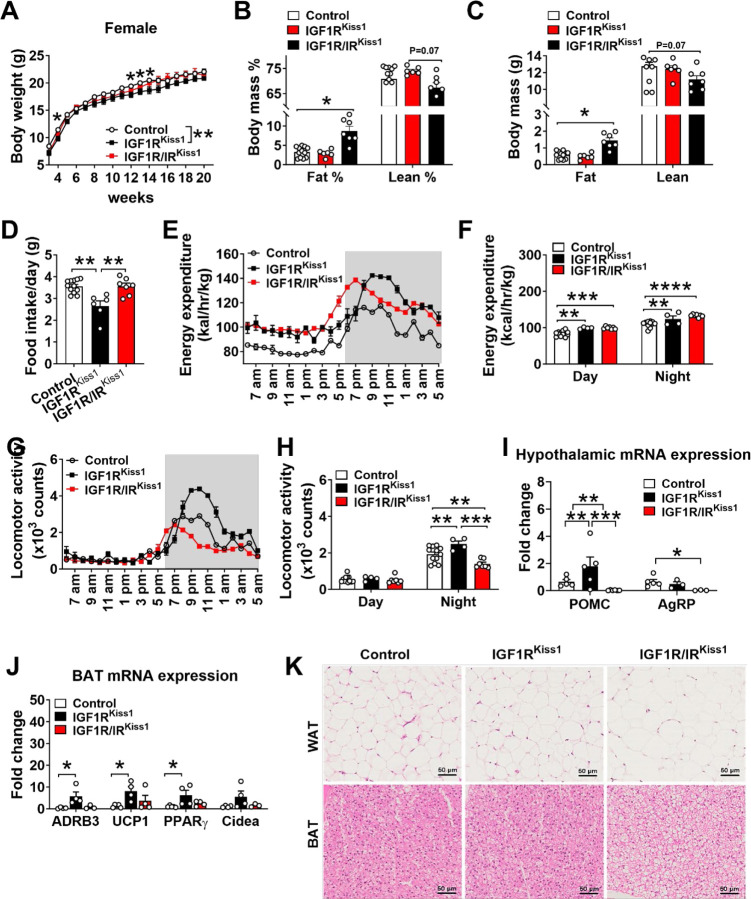

Female IGF1RKiss1 mice were lighter compared to controls (Figure 3A). Percentage body composition of fat and lean tissue (Figure 3B) was similar to controls, as were the absolute values of fat and lean mass (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Altered energy balance in female IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

(A) Body weight curves, (B-C) fat and lean mass percentage and weight, and (D) food intake of female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (E-F) Energy expenditure and (G-H) physical activity in 4-month-old female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (I) Relative expression of POMC and AgRP mRNA in hypothalamus as measured by quantitative PCR in female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (J) Relative expression of thermogenesis markers in BAT as measured by quantitative PCR in female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (K) Representative sliced and HE-stained paraffin-embedded white and brown adipose tissue in 5-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. N=4–12 per genotype. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values. For entire figure, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001, ****p< 0.00001, determined by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test following two-way ANOVA for each time point in A, E, G; or Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA.

In general, calorie needs correlate positively with height/length. Female IGF1RKiss1 mice had lower food intake (Figure 3D) and higher energy expenditure (Figure 3E–F) and physical activity (Figure 3G–H). These findings suggest that loss of IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells led to a leaner phenotype and a tendency toward lower body weights. For mechanistic insight, we measured anorexigenic and orexigenic neuropeptide POMC, AgRP mRNA expression in the hypothalamus. POMC mRNA was higher in female IGF1RKiss1 mice (Figure 3I), in alignment with decreased food intake and improved energy balance. No changes were seen in the AgRP mRNA expression (Figure 3I). We also assessed the expression of genes related to BAT thermogenesis. Female IGF1RKiss1 mice had more mRNA expression of adrenoceptor beta 3 (ADRB3), uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) (Figure 3J). Cidea (Figure 3J) expression did not differ. These results indicate that Kiss1-expressing cells regulate energy balance in response to IGF1 in a manner involving POMC neurons and activation of BAT thermogenesis.

While female IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice did not show changes in body weight or lean mass (Figure 3A–C), simultaneous loss of both IGF1R and IR in Kiss1-expressing cells caused a nearly three-fold increase in fat mass (Figure 3B). In contrast, loss of IR [29] or IGF1R alone from Kiss1-expressing cells did not change body composition in female mice. These findings suggest that IGF1R and IR jointly regulate body fat mass via Kiss1-expressing cells in female mice. The additional deletion of IR in Kiss1-expressing cells reversed the lean phenotype seen in female IGF1RKiss1 related to food intake, physical activity, and brown fat activation (Figure 3D, G–H, K), although energy expenditure remained elevated. In addition, hypothalamic mRNA expression of POMC and AgRP was lower in female IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice than other groups (Figure 3I). These results show that IGF1R and IR signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells have divergent roles in regulating food intake and physical activity in female mice.

Male IGF1RKiss1 mice had lower body weights prior to 6 weeks of age and inconsistently lower body weights in adulthood (Figure 4A) with no change in fat mass and lean mass percentage or absolute value (Figure 4B–C). Male IGF1RKiss1 mice showed a trend toward lower food intake (Figure 4D). Unlike females, male IGF1RKiss1 mice had comparable energy expenditure (Figure 4E–F) and lower physical activity (Figure 4G–H). No change was seen in BAT weight (Figure 4I).

Figure 4. Altered energy balance in male IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

(A) Body weight curves, (B-C) fat and lean body mass percentage and weight, and (D) food intake of male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (E-F) Energy expenditure and (G-H) physical activity in 4-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (I) BAT weight in 5-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. N=4–12 per genotype. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values. For entire figure, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0001, ****p< 0.00001, determined by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test following two-way ANOVA for each time point in A, E, G; or Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA.

Male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice did not exhibit different body weight compared to control mice (Figure 4A), although they showed a higher fat to lean mass ratio (Figure 4B–C). The lack of IR [29] or IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells did not change body composition in males. Consistent with females, these findings suggest that Kiss1 IGF1R and IR also play opposing roles in regulating body fat and lean mass composition in male mice. Male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had lower energy expenditure and locomotor activity in the dark phase compared to IGF1RKiss1 mice and controls, showing that both IGF1R and IR signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells contribute to regulating energy expenditure (Figure 4E–H). Thus, both IGF1R and IR in Kiss1-expressing cells are important in maintaining normal energy balance, and their effects are sex-dependent.

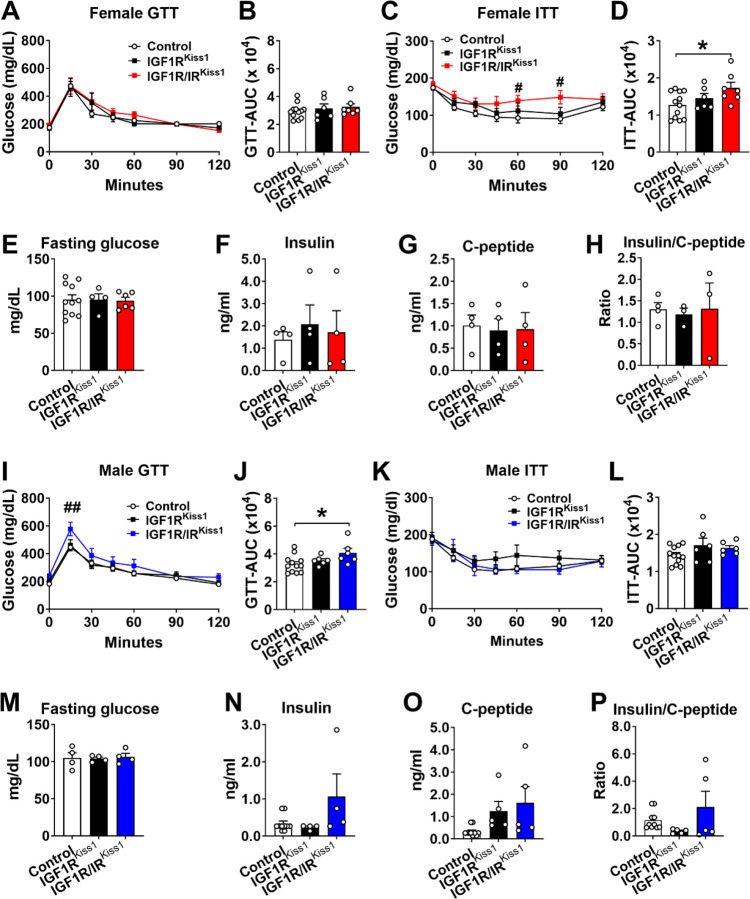

3.4. Disrupted glucose homeostasis in female and male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice

Glucose homeostasis was evaluated in 3-month-old mice. Female IGF1RKiss1 mice had normal glucose regulation as shown by a GTT and ITT (Figure 5A–D). Similarly, we showed the lack of IR in Kiss1-expressing cells did not influence glucose homeostasis [29]. Notably, Female IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had insulin insensitivity compared to controls (Figure 5C–D), suggesting each receptor can compensate for the other’s loss. No changes were seen in fasting glucose, serum levels of insulin, C-peptide, or insulin/C-peptide ratio (Figure 5E–H). As in females, the loss of IGF1R alone in male Kiss1-expressing cells did not change glucose homeostasis (Figure 5I–P). Likewise, the lack of IR alone in Kiss1-expressing cells did not influence glucose homeostasis in male mice [29]. Importantly, male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice exhibited glucose intolerance compared to controls (Figure 5I–J). Thus, IGF1R alone in Kiss1-expressing cells does not control glucose homeostasis, but IGF1R and IR may cooperatively regulate glucose homeostasis in mice of both sexes.

Figure 5. Insulin insensitivity in female IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice and glucose intolerance in male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

(A) Glucose tolerance test (GTT), (B) area under curve (AUC) of GTT (GTT-AUC), (C) insulin tolerance test (ITT) (D) and AUC of ITT (ITT-AUC) in 3-month-old female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (E) Fasting glucose, (F) insulin, (G) C-peptide, and (H) insulin: C-peptide ratio in 3-month-old female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (I) GTT, (J) GTT-AUC, (K) ITT, and (L) ITT-AUC in 3-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (M) Fasting glucose, (N) insulin, (O) C-peptide, and (P) insulin: C-peptide ratio in 3-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. N=6–12 per genotype. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values. For entire figure, *p < 0.05, #p < 0.05 (control vs IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice), determined by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test following two-way ANOVA for each time point in A, C, I and K; or Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA.

3.5. Delayed pubertal development in female and male IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice

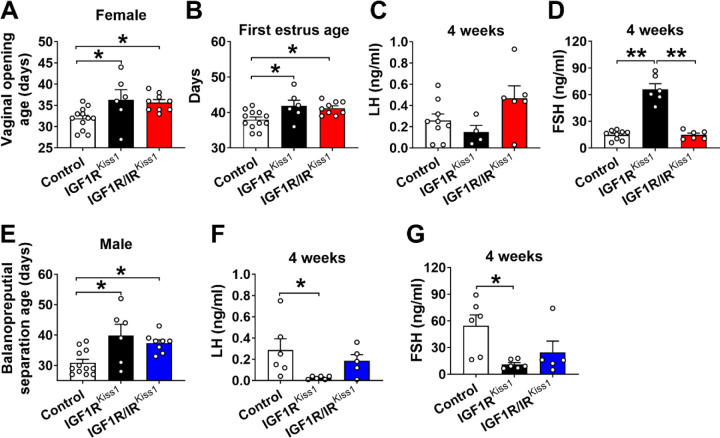

To evaluate the pubertal development in female mice, we examined VO and the timing of the first entrance into estrus. Female IRKiss1 mice experienced a delay in both parameters [29]. Here we found that female IGF1RKiss1 mice experienced VO approximately 3 days later (Figure 6A) and first estrus approximately 4 days later than controls (Figure 6B). No differences were seen in serum LH levels (Figure 6C) between female control and IGF1RKiss1 mice at 4-weeks of age. However, female IGF1RKiss1 mice showed significantly but transiently higher levels of FSH than controls (Figure 6D). Female IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice also had delayed VO age and first estrus age, but IGF1R/IRKiss1 and IGF1RKiss1 mice were comparable (Figure 6A–D).

Figure 6. Delayed pubertal development in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

(A) Vaginal opening age and (B) first estrus age in female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (C-D) Serum levels of LH and FSH in 4 weeks-old female control, IGF1RKiss1, and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (E) Balanopreputial separation age and serum levels of (F) LH and (G) FSH in male control, IGF1RKiss1, and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. N=5–12 per genotype. LH luteinizing hormone, FSH follicle-stimulating hormone. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values. For entire figure, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA.

Balanopreputial separation (BPS) was evaluated as an external sign of puberty in male rodents. Male IGF1RKiss1 mice displayed delayed pubertal development (Figure 6E) associated with lower LH and FSH levels at 4-weeks of age compared to controls (Figure 6F–G). Male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had delayed pubertal development (Figure 6G), but there was no difference between IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. These findings suggest that IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells is required for normal pubertal onset in both female and male mice and normal gonadotropin levels in males during the pubertal transition.

We further performed linear regression analysis to examine whether the delayed onset of puberty was associated with the lower body weight. We found that lower body weight at 3 weeks of age was associated with later onset of puberty as indicated by the VO age in female mice (Supplemental Figure 1A). However, no effects of body weight were seen on the age of pubertal completion in females, namely age of first estrus. For males, balanopreputial separation age was not associated with body weight (Supplemental Figure 1B–C). These findings suggest a particular susceptibility of pubertal initiation to low body weight in females.

3.6. Reproductive deficits in female and male IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice

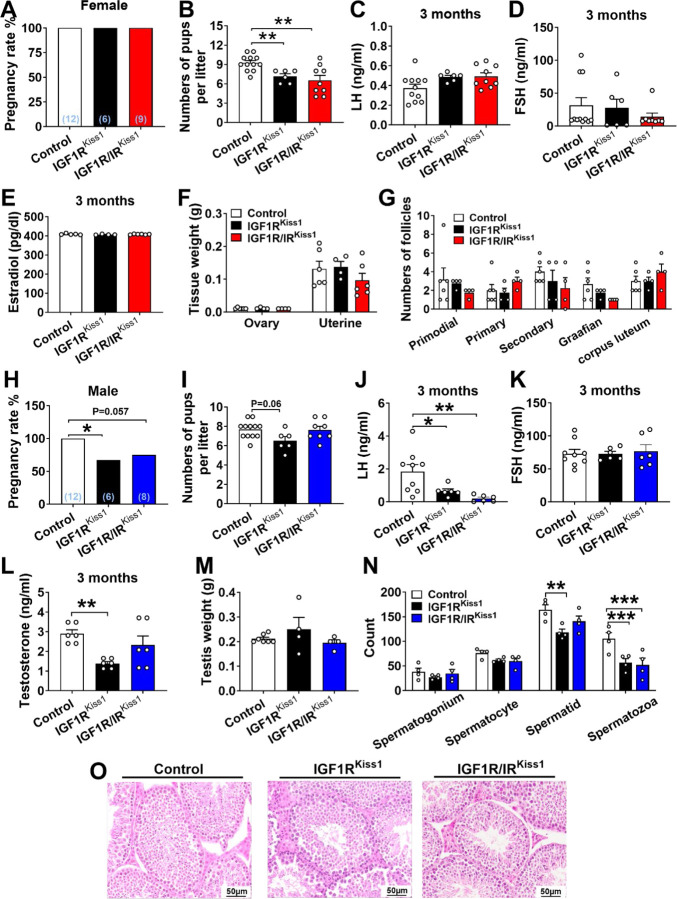

Adult female IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had normal estrus cyclicity (Figure 7). To evaluate adult reproductive function, we performed fertility testing in both female and male mice. Even though the overall pregnancy rate (Figure 8A) in all female groups was comparable, the numbers of pups per litter born to IGF1RKiss1 females mated with control males (Figure 8B) was lower. No differences were seen in serum levels of LH (Figure 8C), FSH (Figure 8D), estradiol (Figure 8E), ovary and uterine weight (Figure 8F), or the numbers of follicles (Figure 7G). No differences were seen between female IGF1R/IRKiss1 and IGF1RKiss1 mice (Figure 8A–G), and IRKiss1 mice did not show impaired fertility [29]. Our findings suggest IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells is not required for ovulation but may play a pregnancy-related role that influences litter size.

Figure 7. Estrus cyclicity in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

(A) estrus cycle length and (B) days spent in each estrus cycle stage in female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. N=6–12 per genotype. P proestrus, E estrus, M metestrus, D diestrus. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values.

Figure 8. Adult fertility in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

(A) Pregnancy rate, (B) numbers of pups/litter, (C) serum LH, (D) FSH and (E) estradiol levels on diestrus in 3- to 4-month-old female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (F) Uterine and ovary weight, and (G) ovarian follicle numbers in 5-month-old female control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (H) Pregnancy rate, (I) numbers of pups/litter, (J) serum LH (K), LH/FSH ratio and (L) testosterone levels in 3- to 4-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (M) Testis weight and (N) analysis of cross-sectional testes seminiferous tubule in 5-month-old male, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. (O) Representative sliced and HE-stained paraffin-embedded testes in 5-month-old male control, IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice. N=4–12 per genotype. All data are shown as means ±SEM with individual values. For the entire figure, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following one-way ANOVA, except G and N determined by Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test following two-way ANOVA.

Male IGF1RKiss1 mice produced fewer pregnancies (Figure 8H) but similar numbers of pups per litter compared to controls (Figure 8I). Male IGF1RKiss1 mice also had lower serum LH, FSH, and testosterone levels (Figure 8J–L). No change in testis weight was seen (Figure 8M). In cross-sections of the seminiferous tubule, male IGF1RKiss1 mice had fewer of spermatids and spermatozoa (Figure 8N), indicating reduced spermatogenesis [47]. Male IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice had similar, or slightly improved, fertility parameters compared to IGF1RKiss1 mice; they tended toward a lower pregnancy rate with a lower LH and LH/FSH ratio and spermatozoa count compared to controls (Figure 8H–N). Representative histological images of seminiferous tubule are shown in Figure 8O. Consistent with females, these findings imply that IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells plays a vital role in regulating adult fertility, gonadotropins, sex hormones, and spermatogenesis in male mice.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we have explored the roles of the growth factors IGF-1 and insulin in the control of metabolism and reproduction, finding that IGF1R, but not IR, signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells is crucial for body growth, energy balance, normal timing of pubertal onset and male reproductive functions. Interestingly, IGF1R effects on energy balance are sex-dependent, in that female IGF1RKiss1 mice had lower body weight and food intake, plus higher energy expenditure and physical activity. We also found Kiss1 IGF1R and IR serve cooperative roles in the regulation of metabolic functions in mice.

The joint roles of IGF1R and IR in peripheral tissues, including fat and muscle, are well established [48; 49]. For example, combined deletion of IGF1R and IR from fat tissue results in cold intolerance due to impaired BAT development and function, while single receptor deletions have normal thermoregulation [48]. In muscle, IRs and IGF1Rs work together to maintain muscle growth; only when both are deleted do the mice have a substantial decrease in fiber size and muscle mass [49]. Similarly, simultaneous loss of IGF1R and IR in Kiss1-expressing cells caused glucose intolerance and insulin insensitivity, which was not seen in IGF1RKiss1 or IRKiss1 mice [29]. We previously showed that deletion of the insulin receptor (IR) alone from Kiss1 expressing cells had no effect on body weight, body fat composition, or food intake [29]. Compared to either IGF1RKiss1 mice or controls, IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice of both sexes exhibited markedly higher fat mass percentages. Overall, our findings identify a cooperative role for IGF1R and IR in Kiss1-expressing cells in the regulation of WAT formation and glucose homeostasis.

The constraints of using conditional gene deletion affect the interpretation of this study. Compensation for loss of signaling may occur during early life, possibly leading to a less pronounced phenotype not reflecting gene function in adult mice. In addition, kisspeptin expression is not limited to the brain; rather, several relevant tissues are reported to contain some kisspeptin producing cells in mice. We and others have previously found low or absent kiss1 expression in the liver, and a lack of expression in muscle, subcutaneous fat, and the gonadal fat pad in healthy mice [29; 50], but kisspeptin is reportedly produced by hepatocytes in response to glucagon stimulation and is increased in mouse models of T2DM [51]. While our lab has previously shown excision of the floxed portion of the IR gene in the liver driven by this Kiss-cre line [29], our results do not reflect the dramatic reduction in systemic insulin sensitivity that has been shown as a consequence of loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes [52]. Further, healthy mature hepatocytes do not express appreciable levels of the IGF1 receptor [53; 54], and we were not able to detect IGF1R gene deletion in this tissue. A potential role for Kiss1 in the mouse kidney and gut is underexplored [29; 55]. The mouse pancreas, and specifically alpha and beta cells have been reported to show kisspeptin immunoreactivity [29; 56]; insulin and IGF1 signaling have important influences on gene expression, cell survival, and proliferation in these cells [57–59]. Again, the phenotype of the mice in this study is milder than would be expected with deletion of the IGF1R or both the IGF1R and IR in cells of the pancreas [59–62]. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that Kiss1 expressing cells in these tissues contribute to the metabolic status of IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice.

The mechanism leading to altered glucose and body composition regulation in IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice may involve direct action on Kiss1 ARH neurons, since they perceive hormonal cues and communicate bidirectionally with neighboring neurons such as POMC neurons that influence reproduction and energy balance [26; 63]. Anorexigenic POMC neurons in the ARH are crucial for maintaining normal energy balance in both humans and rodents [64], while also influencing pubertal timing [23]. We found greater POMC mRNA expression in female IGF1RKiss1 mice, which may relate to their lower food intake and body weight. Female mice have more POMC neurons and higher POMC neuronal activity than males [65], perhaps explaining why female IGF1RKiss1 mice showed a more pronounced metabolic phenotype than males. Additionally, POMC neurons can regulate BAT thermogenesis through the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) [66]. Indeed, expression of BAT thermogenesis and SNS activation genes was higher in female IGF1RKiss1 mice. Therefore, one plausible mechanism for the ability of IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells to modulate energy balance is through communication with POMC neurons and activation of SNS activity and BAT thermogenesis.

IGF1RKiss1 mice displayed mild growth retardation in the form of a shorter body length throughout life. We were unable to detect an endocrine cause for this phenotype since there were no changes in circulating IGF-1 levels in IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice, and limited serum sample volume prevented growth hormone (GH) measurement. Whether neuronal or non-neuronal cells are responsible for the growth deficit is unclear. Homozygous brain IGF1R knockout mice, whose IGF1Rs were depleted in neurons and glia, displayed microcephaly with severe growth retardation [37], while the heterozygous brain IGF1R knockout mice weighed 90% of wild-type controls at 3 months of age and were 5% shorter in length [37]. However, ablation of the IGF1R in somatostatin (SST) neurons, growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) neurons, and/or pituitary somatotrophs did not influence body growth through 14 weeks of age [67; 68]. Thus, there is a potential role for Kiss1 neurons as targets underlying the ability of brain IGF1Rs to modulate growth. It should be noted that GH receptor ablation in kisspeptin neurons did not affect pubertal timing, estrous cycle length, body weight, or body length [69]. Interestingly, during puberty in female mice a subpopulation of ERα positive GHRH neurons become Kiss1-positive neurons, potentially permitting crosstalk between the growth and reproductive axes [70].

We found IGF1RKiss1 mice displayed delayed puberty and a smaller number of pups per litter in females, while males showed delayed puberty, diminished adult fertility, and disrupted gonadotropin and testosterone levels. The low LH levels at 4 weeks and 3 months in male IGF1RKiss1 mice suggest that IGF1R signaling in Kiss1-expressing neurons is necessary for the activation of the male HPG axis during puberty and adult fertility. Measures of adult fertility were similar between IGF1RKiss1 and IGF1R/IRKiss1 mice, suggesting that IGF1R plays a more dominant role in the regulation of reproduction. Some of the reproductive deficits seen in this mouse model may involve the loss of IGF1 receptors in Kiss1-expressing cells within the gonads or other peripheral tissues expressing insulin and IGF1 receptors that impact their function [71; 72]. We and others have reported kiss1 expression in the testis [29; 50]. Indeed, kisspeptin is expressed in mouse Leydig cells and is regulated by reproductive hormone levels [50; 73]. Thus, local impairment of Leydig cell function may contribute to reduced testosterone levels and male subfertility. Kisspeptin is also produced in ovarian granulosa cells as oocytes mature [74; 75], and may be found in the pituitary [76; 77] and uterus [78]. The current Kiss-cre line can drive excision of the floxed portion of the IR gene in the gonads [29]. The inability of IGF1 to promote expression of steroidogenic genes [79] could plausibly explain why female IGF1RKiss1 mice displayed delayed puberty despite normal LH levels and high levels of FSH during the pubertal transition. However, the apparent lack of IGF1R deletion in the ovary argues against the idea that reduced ovarian hormone negative feedback elevates FSH levels in peripubertal IGF1RKiss1 mice. Overall, our results confirm that factors controlling growth and metabolism, such as IGF1, regulate fertility via Kiss1-expressing cells. Additional research is needed to understand the contribution of central and peripheral Kiss1-expressing cells to metabolic factors promoting pubertal development and adult fertility.

5. CONCLUSION

This study assessed the roles of IGF1R and IR in Kiss1-expressing cells in the regulation of metabolic and reproductive functions in mice. We found IGF1R in Kiss1-expressing cells is necessary for the regulation of body growth and the activation of the HPG axis during puberty and adult fertility, particularly in males. IGF1R signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells is critical for maintaining normal metabolic functions, including food intake and energy balance, potentially through central effects on POMC signaling and BAT thermogenesis induction. Notably, our study demonstrates that IGF1R and IR signaling in Kiss1-expressing cells have divergent and compensatory effects in regulating fat mass composition and glucose homeostasis. These findings emphasize the tight link between the systems controlling energy balance and fertility and the critical function of metabolic factors such as IGF-1 in facilitating homeostatic communication.

Supplementary Material

Relationship between (A) vaginal opening age, (B) first estrus age, (C) balanopreputial separation age and body weight at 3 weeks of age. Correlation coefficient is given as a measure of linear regression between the two variables.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HD104418 to JWH and U.S. Department of Agriculture Grant 51000-064-01S to YX.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Herbison A.E., 2016. Control of puberty onset and fertility by gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Nat Rev Endocrinol 12(8):452–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].d’Anglemont de Tassigny X., Colledge W.H., 2010. The role of kisspeptin signaling in reproduction. Physiology (Bethesda) 25(4):207–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cao Y., Li Z., Jiang W., Ling Y., Kuang H., 2019. Reproductive functions of Kisspeptin/KISS1R Systems in the Periphery. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 17(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kirilov M., Clarkson J., Liu X., Roa J., Campos P., Porteous R., et al. , 2013. Dependence of fertility on kisspeptin-Gpr54 signaling at the GnRH neuron. Nat Commun 4:2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wen S., Ai W., Alim Z., Boehm U., 2010. Embryonic gonadotropin-releasing hormone signaling is necessary for maturation of the male reproductive axis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(37):16372–16377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fernandez-Fernandez R., Martini A.C., Navarro V.M., Castellano J.M., Dieguez C., Aguilar E., et al. , 2006. Novel signals for the integration of energy balance and reproduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol 254–255:127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dungan H.M., Clifton D.K., Steiner R.A., 2006. Minireview: kisspeptin neurons as central processors in the regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology 147(3):1154–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Forbes S., Li X.F., Kinsey-Jones J., O’Byrne K., 2009. Effects of ghrelin on Kisspeptin mRNA expression in the hypothalamic medial preoptic area and pulsatile luteinising hormone secretion in the female rat. Neurosci Lett 460(2):143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Navarro V.M., 2020. Metabolic regulation of kisspeptin - the link between energy balance and reproduction. Nat Rev Endocrinol 16(8):407–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Harter C.J.L., Kavanagh G.S., Smith J.T., 2018. The role of kisspeptin neurons in reproduction and metabolism. J Endocrinol 238(3):R173–R183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Padilla S.L., Perez J.G., Ben-Hamo M., Johnson C.W., Sanchez R.E.A., Bussi I.L., et al. , 2019. Kisspeptin Neurons in the Arcuate Nucleus of the Hypothalamus Orchestrate Circadian Rhythms and Metabolism. Curr Biol 29(4):592–604 e594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Luque R.M., Kineman R.D., Tena-Sempere M., 2007. Regulation of hypothalamic expression of KiSS-1 and GPR54 genes by metabolic factors: analyses using mouse models and a cell line. Endocrinology 148(10):4601–4611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Roa J., Garcia-Galiano D., Varela L., Sanchez-Garrido M.A., Pineda R., Castellano J.M., et al. , 2009. The mammalian target of rapamycin as novel central regulator of puberty onset via modulation of hypothalamic Kiss1 system. Endocrinology 150(11):5016–5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Castellano J.M., Navarro V.M., Fernandez-Fernandez R., Nogueiras R., Tovar S., Roa J., et al. , 2005. Changes in hypothalamic KiSS-1 system and restoration of pubertal activation of the reproductive axis by kisspeptin in undernutrition. Endocrinology 146(9):3917–3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oakley A.E., Clifton D.K., Steiner R.A., 2009. Kisspeptin signaling in the brain. Endocr Rev 30(6):713–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Clarkson J., d’Anglemont de Tassigny X., Colledge W.H., Caraty A., Herbison A.E., 2009. Distribution of kisspeptin neurones in the adult female mouse brain. J Neuroendocrinol 21(8):673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Moore A.M., Coolen L.M., Porter D.T., Goodman R.L., Lehman M.N., 2018. KNDy Cells Revisited. Endocrinology 159(9):3219–3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Conde K., Kulyk D., Vanschaik A., Daisey S., Rojas C., Wiersielis K., et al. , 2022. Deletion of Growth Hormone Secretagogue Receptor in Kisspeptin Neurons in Female Mice Blocks Diet-Induced Obesity. Biomolecules 12(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Conde K., Roepke T.A., 2020. 17beta-Estradiol Increases Arcuate KNDy Neuronal Sensitivity to Ghrelin Inhibition of the M-Current in Female Mice. Neuroendocrinology 110(7–8):582–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Qiu J., Stincic T.L., Bosch M.A., Connors A.M., Kaech Petrie S., Ronnekleiv O.K., Kelly M.J., 2021. Deletion of Stim1 in Hypothalamic Arcuate Nucleus Kiss1 Neurons Potentiates Synchronous GCaMP Activity and Protects against Diet-Induced Obesity. J Neurosci 41(47):9688–9701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hessler S., Liu X., Herbison A.E., 2020. Direct inhibition of arcuate kisspeptin neurones by neuropeptide Y in the male and female mouse. J Neuroendocrinol 32(5):e12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Padilla S.L., Qiu J., Nestor C.C., Zhang C., Smith A.W., Whiddon B.B., et al. , 2017. AgRP to Kiss1 neuron signaling links nutritional state and fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(9):2413–2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manfredi-Lozano M., Roa J., Ruiz-Pino F., Piet R., Garcia-Galiano D., Pineda R., et al. , 2016. Defining a novel leptin-melanocortin-kisspeptin pathway involved in the metabolic control of puberty. Mol Metab 5(10):844–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nestor C.C., Qiu J., Padilla S.L., Zhang C., Bosch M.A., Fan W., et al. , 2016. Optogenetic Stimulation of Arcuate Nucleus Kiss1 Neurons Reveals a Steroid-Dependent Glutamatergic Input to POMC and AgRP Neurons in Male Mice. Mol Endocrinol 30(6):630–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Qiu J., Rivera H.M., Bosch M.A., Padilla S.L., Stincic T.L., Palmiter R.D., et al. , 2018. Estrogenic-dependent glutamatergic neurotransmission from kisspeptin neurons governs feeding circuits in females. Elife 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Smith J.T., Acohido B.V., Clifton D.K., Steiner R.A., 2006. KiSS-1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. J Neuroendocrinol 18(4):298–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Donato J. Jr., Cravo R.M., Frazao R., Gautron L., Scott M.M., Lachey J., et al. , 2011. Leptin’s effect on puberty in mice is relayed by the ventral premammillary nucleus and does not require signaling in Kiss1 neurons. J Clin Invest 121(1):355–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Evans M.C., Hill J.W., Anderson G.M., 2021. Role of insulin in the neuroendocrine control of reproduction. J Neuroendocrinol 33(4):e12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Qiu X., Dowling A.R., Marino J.S., Faulkner L.D., Bryant B., Bruning J.C., et al. , 2013. Delayed puberty but normal fertility in mice with selective deletion of insulin receptors from Kiss1 cells. Endocrinology 154(3):1337–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Evans M.C., Rizwan M., Mayer C., Boehm U., Anderson G.M., 2014. Evidence that insulin signalling in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone and kisspeptin neurones does not play an essential role in metabolic regulation of fertility in mice. J Neuroendocrinol 26(7):468–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Qiu X., Dao H., Wang M., Heston A., Garcia K.M., Sangal A., et al. , 2015. Insulin and Leptin Signaling Interact in the Mouse Kiss1 Neuron during the Peripubertal Period. PLoS One 10(5):e0121974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Valverde A.M., Burks D.J., Fabregat I., Fisher T.L., Carretero J., White M.F., Benito M., 2003. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in IRS-2-deficient hepatocytes. Diabetes 52(9):2239–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Matsumoto M., Accili D., 2005. All roads lead to FoxO. Cell Metab 1(4):215–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hong H., Cui Z.Z., Zhu L., Fu S.P., Rossi M., Cui Y.H., Zhu B.M., 2017. Central IGF1 improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in mice. Nutr Diabetes 7(12):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Daftary S.S., Gore A.C., 2005. IGF-1 in the brain as a regulator of reproductive neuroendocrine function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 230(5):292–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wolfe A., Divall S., Wu S., 2014. The regulation of reproductive neuroendocrine function by insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Front Neuroendocrinol 35(4):558–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kappeler L., De Magalhaes Filho C., Dupont J., Leneuve P., Cervera P., Perin L., et al. , 2008. Brain IGF-1 receptors control mammalian growth and lifespan through a neuroendocrine mechanism. PLoS Biol 6(10):e254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Divall S.A., Williams T.R., Carver S.E., Koch L., Bruning J.C., Kahn C.R., et al. , 2010. Divergent roles of growth factors in the GnRH regulation of puberty in mice. J Clin Invest 120(8):2900–2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Cravo R.M., Margatho L.O., Osborne-Lawrence S., Donato J. Jr., Atkin S., Bookout A.L., et al. , 2011. Characterization of Kiss1 neurons using transgenic mouse models. Neuroscience 173:37–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Liu J.L., Grinberg A., Westphal H., Sauer B., Accili D., Karas M., LeRoith D., 1998. Insulin-like growth factor-I affects perinatal lethality and postnatal development in a gene dosage-dependent manner: manipulation using the Cre/loxP system in transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol 12(9):1452–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bruning J.C., Michael M.D., Winnay J.N., Hayashi T., Horsch D., Accili D., et al. , 1998. A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell 2(5):559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Garcia-Galiano D., Borges B.C., Donato J. Jr., Allen S.J., Bellefontaine N., Wang M., et al. , 2017. PI3Kalpha inactivation in leptin receptor cells increases leptin sensitivity but disrupts growth and reproduction. JCI Insight 2(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Torsoni M.A., Borges B.C., Cote J.L., Allen S.J., Mahany E., Garcia-Galiano D., Elias C.F., 2016. AMPKalpha2 in Kiss1 Neurons Is Required for Reproductive Adaptations to Acute Metabolic Challenges in Adult Female Mice. Endocrinology 157(12):4803–4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shi Z., Enayatullah H., Lv Z., Dai H., Wei Q., Shen L., et al. , 2019. Freeze-Dried Royal Jelly Proteins Enhanced the Testicular Development and Spermatogenesis in Pubescent Male Mice. Animals (Basel) 9(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lecka-Czernik B., Stechschulte L.A., Czernik P.J., Sherman S.B., Huang S., Krings A., 2017. Marrow Adipose Tissue: Skeletal Location, Sexual Dimorphism, and Response to Sex Steroid Deficiency. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 8:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Pristera A., Blomeley C., Lopes E., Threlfell S., Merlini E., Burdakov D., et al. , 2019. Dopamine neuron-derived IGF-1 controls dopamine neuron firing, skill learning, and exploration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(9):3817–3826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Yamane T., Shimizu T., Takahashi-Niki K., Takekoshi Y., Iguchi-Ariga S.M.M., Ariga H., 2015. Deficiency of spermatogenesis and reduced expression of spermatogenesis-related genes in prefoldin 5-mutant mice. Biochem Biophys Rep 1:52–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Boucher J., Mori M.A., Lee K.Y., Smyth G., Liew C.W., Macotela Y., et al. , 2012. Impaired thermogenesis and adipose tissue development in mice with fat-specific disruption of insulin and IGF-1 signalling. Nat Commun 3:902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].O’Neill B.T., Lauritzen H.P., Hirshman M.F., Smyth G., Goodyear L.J., Kahn C.R., 2015. Differential Role of Insulin/IGF-1 Receptor Signaling in Muscle Growth and Glucose Homeostasis. Cell Rep 11(8):1220–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Salehi S., Adeshina I., Chen H., Zirkin B.R., Hussain M.A., Wondisford F., et al. , 2015. Developmental and endocrine regulation of kisspeptin expression in mouse Leydig cells. Endocrinology 156(4):1514–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Song W.J., Mondal P., Wolfe A., Alonso L.C., Stamateris R., Ong B.W., et al. , 2014. Glucagon regulates hepatic kisspeptin to impair insulin secretion. Cell Metab 19(4):667–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Michael M.D., Kulkarni R.N., Postic C., Previs S.F., Shulman G.I., Magnuson M.A., Kahn C.R., 2000. Loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes leads to severe insulin resistance and progressive hepatic dysfunction. Mol Cell 6(1):87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Waraky A., Aleem E., Larsson O., 2016. Downregulation of IGF-1 receptor occurs after hepatic linage commitment during hepatocyte differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 478(4):1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kineman R.D., Del Rio-Moreno M., Sarmento-Cabral A., 2018. 40 YEARS of IGF1: Understanding the tissue-specific roles of IGF1/IGF1R in regulating metabolism using the Cre/loxP system. J Mol Endocrinol 61(1):T187–T198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Shoji I., Hirose T., Mori N., Hiraishi K., Kato I., Shibasaki A., et al. , 2010. Expression of kisspeptins and kisspeptin receptor in the kidney of chronic renal failure rats. Peptides 31(10):1920–1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hauge-Evans A.C., Richardson C.C., Milne H.M., Christie M.R., Persaud S.J., Jones P.M., 2006. A role for kisspeptin in islet function. Diabetologia 49(9):2131–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Jiang W.J., Peng Y.C., Yang K.M., 2018. Cellular signaling pathways regulating beta-cell proliferation as a promising therapeutic target in the treatment of diabetes. Exp Ther Med 16(4):3275–3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shapiro M.R., Atkinson M.A., Brusko T.M., 2019. Pleiotropic roles of the insulin-like growth factor axis in type 1 diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 26(4):188–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Kawamori D., Kurpad A.J., Hu J., Liew C.W., Shih J.L., Ford E.L., et al. , 2009. Insulin signaling in alpha cells modulates glucagon secretion in vivo. Cell Metab 9(4):350–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kulkarni R.N., Brüning J.C., Winnay J.N., Postic C., Magnuson M.A., Kahn C.R., 1999. Tissue-specific knockout of the insulin receptor in pancreatic β cells creates an insulin secretory defect similar to that in type 2 diabetes. Cell 96(3):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Kulkarni R.N., Holzenberger M., Shih D.Q., Ozcan U., Stoffel M., Magnuson M.A., Kahn C.R., 2002. beta-cell-specific deletion of the Igf1 receptor leads to hyperinsulinemia and glucose intolerance but does not alter beta-cell mass. Nat Genet 31(1):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Takatani T., Shirakawa J., Shibue K., Gupta M.K., Kim H., Lu S., et al. , 2021. Insulin receptor substrate 1, but not IRS2, plays a dominant role in regulating pancreatic alpha cell function in mice. J Biol Chem 296:100646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Nestor C.C., Kelly M.J., Ronnekleiv O.K., 2014. Cross-talk between reproduction and energy homeostasis: central impact of estrogens, leptin and kisspeptin signaling. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 17(3):109–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Belgardt B.F., Okamura T., Bruning J.C., 2009. Hormone and glucose signalling in POMC and AgRP neurons. J Physiol 587(Pt 22):5305–5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wang C., He Y., Xu P., Yang Y., Saito K., Xia Y., et al. , 2018. TAp63 contributes to sexual dimorphism in POMC neuron functions and energy homeostasis. Nat Commun 9(1):1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Zhang W., Bi S., 2015. Hypothalamic Regulation of Brown Adipose Tissue Thermogenesis and Energy Homeostasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 6:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Chaves F.M., Wasinski F., Tavares M.R., Mansano N.S., Frazao R., Gusmao D.O., et al. , 2022. Effects of the Isolated and Combined Ablation of Growth Hormone and IGF-1 Receptors in Somatostatin Neurons. Endocrinology 163(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Al-Samerria S., Radovick S., 2021. The Role of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) in the Control of Neuroendocrine Regulation of Growth. Cells 10(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Bohlen T.M., Zampieri T.T., Furigo I.C., Teixeira P.D., List E.O., Kopchick J., et al. , 2019. Central growth hormone signaling is not required for the timing of puberty. J Endocrinol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Garcia-Galiano D., Cara A.L., Tata Z., Allen S.J., Myers M.G. Jr., Schipani E., Elias C.F., 2020. ERalpha Signaling in GHRH/Kiss1 Dual-Phenotype Neurons Plays Sex-Specific Roles in Growth and Puberty. J Neurosci 40(49):9455–9466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Neirijnck Y., Calvel P., Kilcoyne K.R., Kuhne F., Stevant I., Griffeth R.J., et al. , 2018. Insulin and IGF1 receptors are essential for the development and steroidogenic function of adult Leydig cells. FASEB J 32(6):3321–3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Sekulovski N., Whorton A.E., Shi M., Hayashi K., MacLean J.A., 2nd, 2020. Periovulatory insulin signaling is essential for ovulation, granulosa cell differentiation, and female fertility. FASEB J 34(2):2376–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Sharma A., Thaventhiran T., Minhas S., Dhillo W.S., Jayasena C.N., 2020. Kisspeptin and Testicular Function-Is it Necessary? Int J Mol Sci 21(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chakravarthi V.P., Ghosh S., Housami S.M., Wang H., Roby K.F., Wolfe M.W., et al. , 2021. ERbeta regulated ovarian kisspeptin plays an important role in oocyte maturation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 527:111208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chakravarthi V.P., Khristi V., Ghosh S., Yerrathota S., Dai E., Roby K.F., et al. , 2018. ESR2 Is Essential for Gonadotropin-Induced Kiss1 Expression in Granulosa Cells. Endocrinology 159(11):3860–3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Gutierrez-Pascual E., Martinez-Fuentes A.J., Pinilla L., Tena-Sempere M., Malagon M.M., Castano J.P., 2007. Direct pituitary effects of kisspeptin: activation of gonadotrophs and somatotrophs and stimulation of luteinising hormone and growth hormone secretion. J Neuroendocrinol 19(7):521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ikeda Y., Tagami A., Komada M., Takahashi M., 2017. Expression of Kisspeptin in Gonadotrope Precursors in the Mouse Pituitary during Embryonic and Postnatal Development and in Adulthood. Neuroendocrinology 105(4):357–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Radovick S., Babwah A.V., 2019. Regulation of Pregnancy: Evidence for Major Roles by the Uterine and Placental Kisspeptin/KISS1R Signaling Systems. Semin Reprod Med 37(4):182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Zhou P., Baumgarten S.C., Wu Y., Bennett J., Winston N., Hirshfeld-Cytron J., Stocco C., 2013. IGF-I signaling is essential for FSH stimulation of AKT and steroidogenic genes in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 27(3):511–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Relationship between (A) vaginal opening age, (B) first estrus age, (C) balanopreputial separation age and body weight at 3 weeks of age. Correlation coefficient is given as a measure of linear regression between the two variables.