Abstract

Background and Objectives:

To explore the prevalence and characteristics of secondary bacterial infections among patients suffering from mucormycosis following COVID-19 infection.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional, retrospective analysis from March 2020 to April 2022 at Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex in Tehran. The study included patients with histopathologically confirmed mucormycosis and documented secondary bacterial infections. We extracted and analyzed data from hospital records using SPSS software, version 26.

Results:

The study comprised 27 patients, with a predominance of females (70.4%) and an average age of 56 years. The majority of these patients (63%) had pre-existing diabetes mellitus. The severity of their COVID-19 infections varied. Treatment regimens included immunosuppressive drugs and antibiotics. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis was the most common form observed. The predominant secondary infections involved the urinary tract, respiratory system, bloodstream (bacteremia), and soft tissues, with resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumoniae being the most frequently identified microorganisms. Notably, cases of bacteremia and pneumonia exhibited a higher mortality rate. Ultimately, 55.6% of patients were discharged, while 44.4% succumbed to their infections.

Conclusion:

Patients recovering from COVID-19 with mucormycosis are significantly susceptible to secondary bacterial infections, particularly those with diabetes mellitus or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Such infections compound the morbidity and mortality risks in this vulnerable patient cohort.

Keywords: Bacterial infection, Mucormycosis, COVID-19, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli

INTRODUCTION

Despite growing understanding of COVID-19 and its complications, the exploration of secondary bacterial infections in patients with mucormycosis, a serious post-COVID-19 complication, remains inadequately addressed. The incidence of these super-infections varies widely, reported between 5% and 27% across various studies (1), indicating a significant threat to patient recovery. Notably, the co-occurrence of COVID-19 with bacterial and fungal infections spans a wide range, from 50% to as high as 100% in certain studies, highlighting the critical impact of such infections on patient survival rates (2, 3).

A concerning trend is the substantial occurrence of secondary bacterial infections, found in over 40% of patients according to research conducted in China (4). Fungal infections, particularly mucormycosis and Rhizopus, which were traditionally associated with severe immune deficiencies, have now been frequently observed in COVID-19 patients (5). The rise in fungal infections, especially among those hospitalized in intensive care units, underscores an emerging crisis (6). This trend is alarmingly evident in India and South Asian countries, which have reported the highest numbers of mucormycosis cases in the context of COVID-19, with India alone recording over 41,000 cases and more than 3,200 deaths related to this fungal infection (4–6).

The vulnerability of COVID-19 patients to such infections can be partly attributed to the impairment of the immune system, characterized by a significant reduction in lymphocytes, notably T-lymphocytes (7). The situation is exacerbated for critically ill patients who receive immunosuppressive drugs and broad-spectrum antibiotics, further weakening their immune defenses (8).

The pivotal role of rapid and timely diagnosis in reducing mortality rates and healthcare costs cannot be overstated (9). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the average survival rate for mucormycosis patients hovers around 54%, although this figure varies based on the type of microorganism and the patient’s overall condition, with a range from 0% to 50% (10).

This patient cohort faces increased mortality risk due to various factors, including rapid progression of infection, significant immunosuppression, and high-risk comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and kidney failure. Additionally, the lack of positive results in blood cultures or KOH smears in fungal diseases often leads to delayed diagnoses, compounding the risk of mortality. These challenges are particularly pronounced among critically ill patients, highlighting an urgent need for focused research (11).

Given the paucity of research on bacterial super-infections and their associated risk factors in post-COVID-19 mucormycosis patients, our study seeks to fill this gap by investigating the prevalence and types of secondary bacterial infections in this vulnerable patient population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional retrospective analysis was conducted at Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran, from March 2020 to April 2021. This study focused on 27 patients who were diagnosed with mucormycosis post-COVID-19, confirmed via histopathology from biopsy samples, and who subsequently developed secondary bacterial infections. Eligibility criteria required participants to be aged 18 years or older. Patients with fungal infections other than mucormycosis or with incomplete medical records were excluded from the study.

Data collection included demographic details (age, gender), clinical signs and symptoms at the time of admission, biopsy pathology results, the interval between COVID-19 infection and mucormycosis diagnosis, underlying health conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus), and antibiotic treatments. Laboratory tests assessing microbial sensitivity and resistance were also reviewed.

A specialized questionnaire, designed by our research team, was utilized to gather data. Information recorded during the hospital stay covered catheter-related infections, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, abdominal infections, and skin infections. Microbiological analysis focused on the site of infection, identification of microorganisms, and antibiogram results. Mortality rates and lengths of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) were documented, with data sourced from Imam Khomeini Hospital’s medical records and electronic patient databases.

This methodological approach was intended to offer a comprehensive evaluation of the prevalence and characteristics of secondary bacterial infections in patients with post-COVID-19 mucormycosis, contributing insights for better management and prognosis of these conditions.

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, with all participants providing informed consent prior to inclusion. The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, as amended in 2000 (Ethics code: IR.TUMS.IKHC.REC.1401.065).

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 26. Quantitative data following a normal distribution were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while qualitative data were presented as frequency (%). The Chi-Squared test was applied to qualitative variables, and the Student’s t-test was used for analyzing continuous quantitative variables with normal distributions. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses.

RESULTS

In a comprehensive analysis of 27 COVID-19 patients, we observed a varied demographic profile: 70.4% (19 patients) were female, and 29.6% (8 patients) were male, with an age range from 20 to 84 years. The mean age was 56 (Table 1). Notably, a significant portion of the cohort, 63% (17 patients), presented with diabetes mellitus (DM) as a pre-existing comorbidity.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and risk factors of patients

| Variables | Number (n) = 27 | Percent | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 8 (29.6%) | 27 (100%) |

| Female | 19 (70.4%) | ||

| Prognosis | Discharge | 15 (55.6%) | 27 (100%) |

| Death | 12 (44.4.%) | ||

| Underlying Disease | Diabetes mellitus | 17 (62.9%) | 17 (62.9%) |

| COVID-19 severity | Mild | 14 (51.9%) | 27 (100%) |

| Moderate | 6 (22.2%) | ||

| Severe | 7 (25.9) | ||

| Immunosuppressive drug for COVID-19 treatment | Dexamethasone | 9 (33.3%) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Prednisolone | 6 (22.2%) | ||

| Tocilizumab | 1 (3.7%) | ||

| Antibiotics | Azithromycin | 7 (25.9%) | 11 (40.7%) |

| Ceftriaxone | 3 (11.1%) | ||

| Clindamycin | 2 (7.5%) | ||

| Vancomycin | 1 (3.7%) | ||

| Meropenem | 1 (3.7%) | ||

| Biologic drug for underlying disease | Cellcept | 2 (7.5%) | 2 (7.5%) |

| Syndromes | UTI | 9 (33.3%) | 9 (33.3%) |

| Pneumonia | 7 (25.9%) | 7 (25.9%) | |

| Bacteremia | 6 (22.2%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| Cellulitis | 4 (14.8%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Brain abscess | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Meningitis | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| Maxillary sinusitis | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.7%) |

Our examination of COVID-19 severity in hospitalized patients revealed that 51.9% exhibited mild symptoms, 25.9% severe symptoms, and 22.2% moderate symptoms. It was observed that patients typically developed signs of secondary bacterial infections approximately 12.7 days following the onset of COVID-19.

With respect to treatment, immunotherapy, specifically tocilizumab, was administered to 48.1% of the cases. Antibiotic therapy, with azithromycin as the predominant choice, was prescribed to 40.7% of the patients. The employment of dexamethasone and remdesivir was also significant, representing 37% and 29.6% of the treatment protocols, respectively. Additional treatments included methylprednisolone, prednisolone, favipiravir, and tocilizumab, tailored to the individual needs of the patients (Table 1).

Statistical analysis highlighted a significant association between the mortality rate and the type of secondary bacterial infection (P-value = 0.001). A notably high mortality rate was observed in patients with bacteremia (83.3%, 5 patients) and pneumonia (80%, 4 patients). Conversely, no fatalities were reported in patients with urinary tract infections and soft tissue infections, indicating that specific secondary infections may significantly influence COVID-19 patient outcomes (Table 2). The specific prevalence rates and percentages of bacterial species in blood culture profiles of key pathogens include Acinetobacter baumannii (5 patients, 18.5%), Escherichia coli (7 patients, 25.9%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (4 patients, 14.8%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (3 patients, 11.1%), Enterobacteriaceae (4 patients, 14.8%), and Staphylococcus aureus (2 patients, 7.4%).

Table 2.

Comparison of the significance level of different variables with secondary bacterial infections in patients

| Variable | Secondary Bacterial Infection | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Bacteremia | UTI | cellulitis | pneumonia | |||

| Covid-19 Severity | Moderate | 4 (66.7%) | 8 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 2 (40%) | 0.61 |

| Severe | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (60%) | ||

| Mortality | Discharge | 1 (16.7%) | 8 (100%) | 3 (100%) | 1 (20%) | 0.001 |

| Death | 5 (83.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (80%) | ||

| Receiving Antibiotics | Yes | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (50%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (40%) | 0.97 |

| No | 4 (66.7%) | 4 (50%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (60%) | ||

| Underlying Diabetes | Positive | 3 (50%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (60%) | 0.65 |

| Negative | 3 (50%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) | ||

| Receiving Immunosuppressive Medication | Yes | 3 (50%) | 3 (37.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (60%) | 0.97 |

| No | 3 (50%) | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (40%) | ||

| Dexamethasone | Yes | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) | 0.87 |

| No | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (100%) | 3 (60%) | ||

| Methylprednisolone | Positive | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (40%) | 0.29 |

| Negative | 5 (83.3%) | 8 (100%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (60%) | ||

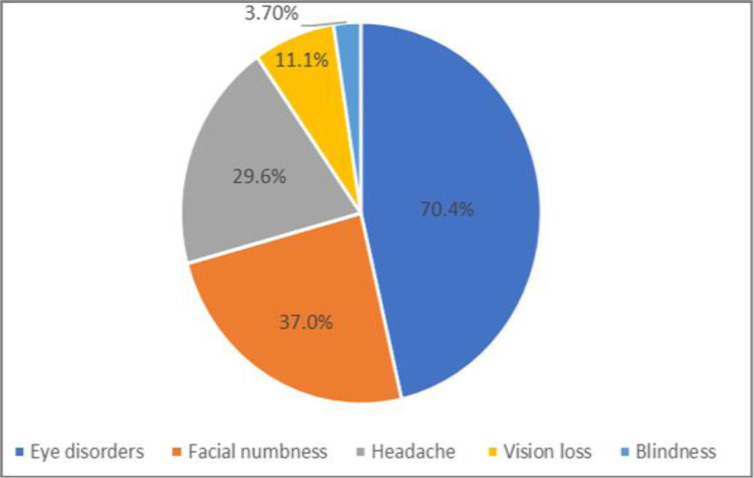

We have included three additional graphs to clearly illustrate the distribution of secondary infections, treatment regimens, and mortality rates. Clinically, a significant proportion of patients (70.4%) presented with visual and eye disorders, including symptoms like eye swelling, secretions, reduced vision, and, in one case, blindness. Additional common symptoms reported were facial numbness and headaches, emphasizing the diverse clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of complications of the disease in patients with secondary infection

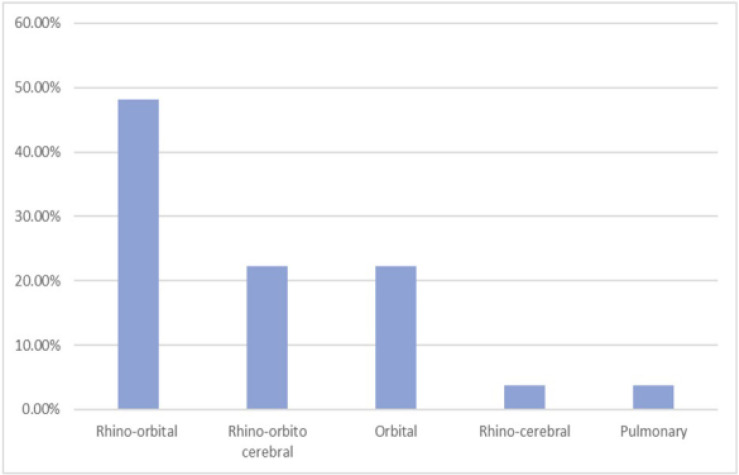

In terms of mucormycosis types, our study identified rhino-orbital mucormycosis as the most common, followed by rhino-orbital-cerebral and orbital mucormycosis. Less frequently observed types were rhino-cerebral and pulmonary mucormycosis. For these conditions, liposomal amphotericin B was the preferred treatment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The prevalence type of mucormycosis post COVID-19 patients

DISCUSSION

Our investigation into the prognosis of mucormycosis post-COVID-19, particularly in patients developing bacterial superinfections, sheds light on an area not extensively explored in medical research. Analysis of 27 patients revealed a predominant female demographic (70.4%) with an average age of 56. A notable finding was the 13-day interval between COVID-19 contraction and the emergence of bacterial or fungal infections. Significantly, 63% of these patients had pre-existing diabetes mellitus (DM), underscoring the interplay between chronic conditions and acute infectious complications.

The augmented risk of fungal infections such as mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients, attributed to the widespread application of immunosuppressive and glucocorticoid treatments, resonates with our findings. This risk escalates particularly in patients with DM, hematological cancers, or those receiving chemotherapy, aligning with observed trends in Asia where DM is more prevalent compared to the Western prevalence of conditions like hematological cancers and organ transplants (4).

Echoing the complexity of managing mucormycosis, as illustrated by Garg et al. in a case involving DM and end-stage renal disease (12), our study found a significant portion of patients (70%) experiencing visual disturbances, with nearly half facing mortality. This highlights the severe impact of co-infections on patient outcomes.

The isolation of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter (MDR) as a common pathogen in our cohort, particularly lethal, mirrors broader concerns about antibiotic resistance. Falcone’s observations of secondary infections in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, emphasizing the complications arising from broad-spectrum antibiotics and immunosuppressives, support our findings (5). The congruence with Selarka et al.’s study, emphasizing the DM prevalence among mucormycosis patients and its correlation with higher mortality rates (13), further validates our results. Sharma’s review, identifying DM as a pivotal risk factor for mucormycosis, is echoed across multiple studies, reinforcing the critical nature of this comorbidity (12–15).

Our study identified rhino-orbital mucormycosis as the most prevalent form, a trend also observed by Singh AK in India (16), while Mehta’s in-depth case study on rhino-orbital mucormycosis (17), underscores the challenges in managing such infections. The significant detection of MDR Acinetobacter, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Escherichia coli, akin to findings by Meaved et al. in critically ill COVID-19 patients, alongside Garcia Vidal’s research, illustrates the diverse microbial landscape in these patients (14). These study findings underscore the urgent need for tailored treatment strategies for post-COVID-19 mucormycosis patients, especially those with diabetes mellitus. Early identification and treatment of secondary bacterial infections could be critical in reducing mortality rates.

A limitation of this study is its small sample size and focus on patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus. Future research should investigate a broader patient population and develop specific management strategies for the resistant pathogens identified in this study.

CONCLUSION

Based on our findings, we recommend close monitoring of post-COVID-19 mucormycosis patients for secondary bacterial infections, particularly those with diabetes mellitus. Additionally, adjustment of treatment protocols to include surveillance strategies for resistant bacterial strains is necessary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blaize M, Mayaux J, Nabet C, Lampros A, Marcelin A-G, Thellier M, et al. Fatal invasive aspergillosis and coronavirus disease in an immunocompetent patient. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26: 1636–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daria S, Asaduzzaman M, Shahriar M, Islam MR. The massive attack of COVID-19 in India is a big concern for Bangladesh: the key focus should be given on the interconnection between the countries. Int J Health Plann Manage 2021; 36: 1947–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao J, Tu W-J, Cheng W, Yu L, Liu Y-K, Hu X, et al. Clinical features and short-term outcomes of 102 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71 :748–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma A, Goel A. Mucormycosis: risk factors, diagnosis, treatments, and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2022; 67: 363–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falcone M, Tiseo G, Giordano C, Leonildi A, Menichini M, Vecchione A, et al. Predictors of hospital-acquired bacterial and fungal superinfections in COVID-19: a prospective observational study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 1078–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lansbury L, Lim B, Baskaran V, Lim WS. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2020; 81: 266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharifipour E, Shams S, Esmkhani M, Khodadadi J, Fotouhi-Ardakani R, Koohpaei A, et al. Evaluation of bacterial co-infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharyya A, Sarma P, Sharma DJ, Das KK, Kaur H, Prajapat M, et al. Rhino-orbital-cerebral-mucormycosis in COVID-19: A systematic review. Indian J Pharmacol 2021; 53: 317–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prakash H, Ghosh AK, Rudramurthy SM, Singh P, Xess I, Savio J, et al. A prospective multicenter study on mucormycosis in India: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Med Mycol 2019; 57: 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman FI, Islam MR, Bhuiyan MA. Mucormycosis or black fungus infection is a new scare in South Asian countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associated risk factors and preventive measures. J Med Virol 2021; 93: 6447–6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Veisi A, Bagheri A, Eshaghi M, Rikhtehgar MH, Rezaei Kanavi M, Farjad R. Rhino-orbital mucormycosis during steroid therapy in COVID-19 patients: A case report. Eur J Ophthalmol 2022; 32: NP11–NP16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg D, Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Ramachandran R, Kaur H, Bhalla A, et al. Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) associated mucormycosis (CAM): case report and systematic review of literature. Mycopathologia 2021; 186: 289–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selarka L, Sharma S, Saini D, Sharma S, Batra A, Waghmare VT, et al. Mucormycosis and COVID-19: an epidemic within a pandemic in India. Mycoses 2021; 64: 1253–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meawed TE, Ahmed SM, Mowafy SMS, Samir GM, Anis RH. Bacterial and fungal ventilator associated pneumonia in critically ill COVID-19 patients during the second wave. J Infect Public Health 2021; 14: 1375–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh AK, Singh R, Joshi SR, Misra A. Mucormycosis in COVID-19: a systematic review of cases reported worldwide and in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2021; 15: 102146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta S, Pandey A. Rhino-orbital mucormycosis associated with COVID-19. Cureus 2020; 12(9): e10726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]