In the mid-1990s the BMJ published a series on the World Health Organization by Fiona Godlee, an assistant editor at the journal. Godlee argued that WHO was in crisis—lacking effective leadership, direction, and priorities. Seven years later, has the organisation successfully reinvented itself?

In her book Betrayal of Trust, health writer Laurie Garrett described WHO's decade of decline: “The World Health Organization, once the conscience of global health, lost its way in the 1990s. Demoralized, rife with rumors of corruption, and lacking in leadership, WHO floundered.”1

Fiona Godlee, in her series in the BMJ (box B1), came to a similar conclusion. She argued that Hiroshi Nakajima, then director general, had failed to communicate a coherent strategic direction for WHO. Its six regional offices were bureaucratic, rife with cronyism, and operating autonomously from headquarters and it had little impact at country level. Donors questioned WHO's effectiveness, seeing better “value for money” from channelling their funds into other agencies, especially the World Bank. Though WHO still carried out important work setting standards and giving technical support to countries, the bank took its place as the most influential global health agency. At the end of the series, Richard Smith wrote an editorial in which he challenged WHO to “change or die.”2

Summary points

In the 1990s WHO came under fire for poor leadership and lack of direction

Gro Brundtland took office as director general in July 1998 and attempted sweeping reforms

Brundtland prioritised WHO's activities and launched important global health campaigns

She restored WHO'S credibility with donors and helped to place health on the international development agenda

But her management changes have been unpopular, and critics argue that WHO is still too influenced by its donors

Brundtland's reforms have not been felt where they matter most—at country level

Box 1.

Fiona Godlee's BMJ series on WHO

A new leader

One woman was charged with saving the organisation. Gro Harlem Brundtland, a former prime minister of Norway, took office as director general on 21 July 1998 and promised radical reform for WHO. She restructured it, prioritised its activities, and launched new health campaigns. WHO made a comeback to the global political stage.

But in a few important ways, WHO is still struggling. Its new structure has created a different set of problems for the organisation. There are serious questions about whether Brundtland's reforms have been felt at country level. And in a surprise move, on 23 August this year Brundtland announced that she would not stand for a second term. A new director general takes office next July, leaving the future of Brundtland's reforms uncertain.

What impact have the reforms had on WHO's most important constituency—the poor? How has WHO engaged with other players in health? How is it responding to the multiplication of new global health initiatives? I will address these questions over the next few weeks, and begin here by discussing the reforms themselves.

Methods

I visited WHO's headquarters in Geneva, where I interviewed staff at many levels of the organisation, including Brundtland. I also interviewed WHO staff working in developing countries, former members of Brundtland's cabinet, three regional directors, health academics, and members of multinational and bilateral health agencies and non-governmental organisations. Finally, I read a wide selection of WHO documents, minutes of the meetings of WHO's executive board and the World Health Assembly, and journal articles and books dealing with WHO reform.

Mounting pressure for change

The five years before Brundtland came to power saw a growing international reform movement. This began from within WHO in 19933 and gained momentum with Godlee's BMJ series. Julio Frenk, Mexico's minister of health, a former executive director and a key architect of the Brundtland reforms, said that Godlee's series was “influential in shaping a debate about WHO, and internally it brought the critical situation to the fore. There was a realisation that WHO was at a crossroads.”

Which direction should it take? Two government funded studies pointed the way.

A 1995 study provided evidence that WHO's donors were calling the shots (box B2).4 The WHO has two funding sources. Its regular budget, frozen at about $800m (£517m; €817m) per two-year budget period, comes from dues paid by its member states. Its main funding source is from additional voluntary contributions (extrabudgetary funds) from a handful of donor countries, now worth $1.4bn per budget period. The study found that donors could influence how their donations were spent. The problem with this practice is that it can hinder WHO's ability to set its own long term priorities and budget for them accordingly.

Box 2.

How donors can call the shots

A 1997 study examined the support that WHO was giving to countries to develop their health systems.5 It found that some of the world's poorest countries received the least amount of support.

A series of gatherings of international health experts in 1996 and 1997 concluded that WHO's activities were uncoordinated, that its regional structure needed examining, and that the organisation was facing competition from other international health initiatives.6 The meetings led to a declaration of issues that the next director general should address (box B3).7

Box 3.

Key issues facing Brundtland at the start of her term7

- Defining WHO's essential functions

- Revising governance structures to give greater voice to new actors on the global stage

- Developing more effective mechanisms for responding to national requirements for capacity strengthening

- Creating effective arrangements for coordination between WHO and other agencies

- Enhancing the organisation's authority in scientific and technical matters

- Reassessing the relationships between WHO's headquarters, regional offices, and country offices

- Revising procedures for the allocation of resources to ensure that they give full weight to the needs of individual nations

- Ensuring that staff positions are created on the basis of need and filled on the basis of merit

Brundtland defines her agenda

How would Brundtland respond? Two months before taking office, she made her first speech to the World Health Assembly, the annual policy meeting of WHO member states.8 She promised major organisational reform. She laid out four strategic directions for WHO: reducing the burden of disease, particularly in poor countries; reducing risks to health; creating sustainable health systems; and “developing an enabling policy and institutional environment in the health sector.”9

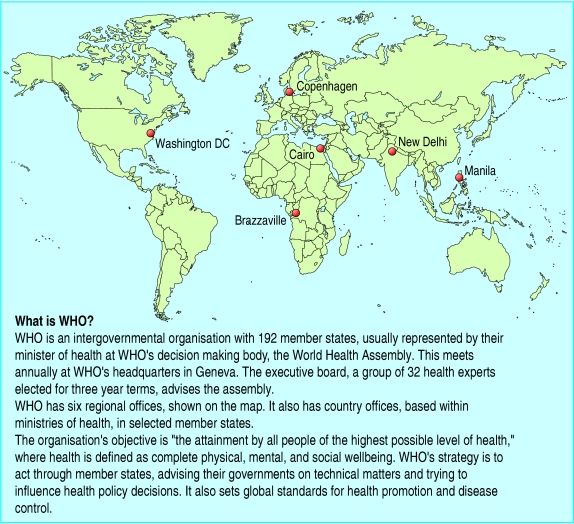

The most important pledge she made—a pledge that some will judge her term by—was to create “one WHO.” We must be able to say, she said, “WHO is one. Not two—meaning one financed by the regular budget and one financed by extrabudgetary funds. Not seven—meaning Geneva and the six regional offices.”8

A hundred days of change

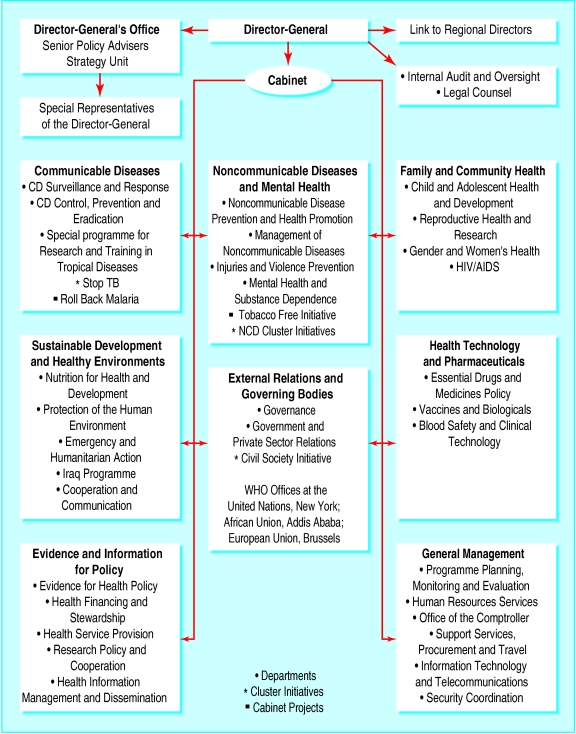

The first three months of Brundtland's leadership saw massive upheaval aimed at giving WHO a leaner structure. She reduced 50 programmes to 35 departments and grouped them into nine (now eight) clusters at headquarters (figure). The clusters were meant to reflect WHO's new strategic directions.

Gone were the assistant director general posts, widely held to be political appointments. Instead, an executive director was assigned to each cluster. This post was supposed to be held by a technical expert who controlled the cluster's budget. The idea was to create a more horizontal structure while bringing technical expertise towards WHO's centre.

Brundtland and her executive directors became a tight, government-style cabinet. Frenk believes that the cabinet “forces the executive directors to make collective decisions. Before these changes, WHO was a highly fragmented, feudal organisation.” But one senior WHO insider said that there has been a gradual reversion to the old hierarchical system. There has also been a constant reshuffling of Brundtland's cabinet—only one original cabinet member remains. Brundtland argues that this was necessary to get the right mix of people, but many WHO staff say the changes created instability in the organisation.

New partners, new campaigns

Brundtland galvanised important health campaigns with new partners from both the public and private sector.

In the months before taking office, she decided on two campaigns. The Tobacco Free Initiative, aimed at curbing the 4 million annual deaths from tobacco, led to two firsts for WHO. In October 2000, negotiations began towards WHO's first international treaty, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, set to be completed in May 2003.10 Signatory states will be legally bound to implement measures for reducing tobacco consumption. In October 2000 WHO held its first public hearings, allowing civil society groups to give their input to the treaty.

The other campaign was Roll Back Malaria,11 a public-private partnership that Brundtland called a “pathfinder project.”12 Malaria causes at least 3000 deaths a day, and the partnership aims to halve this rate by 2010.11 Brundtland made no apologies for involving the private sector; she said it had “an important role to play, both in technology development and the provision of services.”8

Partnerships have been a defining feature of Brundtland's term. But many of WHO's partners say that the organisation is finding it hard to give up its traditional driver's seat status. A recent external review of Roll Back Malaria found that WHO had a tendency to “go it alone” without adequate consultation with partners.13

A roadmap for WHO policy

“Brundtland,” said Derek Yach, one of WHO's executive directors, is a “data oriented person.” Over the course of her term, she emphasised the need for WHO to base its work on empirical evidence.

As her roadmap for guiding WHO policy, she chose the World Bank's World Development Report 1993.14 This measured the global burden of disease and the cost effectiveness of different health interventions using a new unit, the disability adjusted life year (DALY). The DALY was highly controversial (box B4).15,16 The report argued that countries should prioritise cost effective interventions instead of broadly strengthening their health systems.

Box 4.

Divided opinion on the DALY

Brundtland brought many of the report's authors from Harvard to establish a new unit, Evidence and Information for Policy. The WHO, said one academic in global health, had become “a branch of Harvard and the World Bank.”

The unit had a profound impact on Brundtland. She established priorities for the organisation (box B5) that are heavily influenced by the DALY.17 She talked of a “new universalism” that sees cost effectiveness as a tool for choosing which health services governments should provide.18 And it was this unit that produced the World Health Report 2000, released in June 2000, which measured the performance of countries' health systems and ranked them into a league table.19

Box 5.

WHO's global priorities16

The report was explosive. Many countries objected to their ranking; the report's methods were savagely criticised and its relevance to developing countries was questioned.20,21 At its meeting in January 2001, WHO's executive board, a group of 32 health experts that advises the World Health Assembly, requested that Brundtland commission an external review of the report's methods.22 The future of the health systems ranking is now uncertain.

Was ranking a valuable exercise? It succeeded in igniting an important debate about what makes for a good health system and why various countries perform so differently. But Brundtland handled the release of the report poorly. There was too much secrecy around the process of data collection, and inadequate consultation with developing countries before its release. Many WHO staff I spoke to complained of an unhealthy atmosphere at headquarters in which internal dissent about the report was stifled.

Progress towards “one WHO”

What progress did Brundtland make towards streamlining activities at headquarters with those of the regions?

One stumbling block was the long-running autonomy of the regions. A 1946 report on an international meeting to elaborate WHO's constitution noted that the Pan-American Sanitary Bureau, which became WHO's regional office for the Americas, “desired to continue the Bureau as an automatous body.”23 The director general has little authority over the regional directors because she does not elect them—they are elected, like her, by WHO's member states, which puts them all on an equal footing. Reform of WHO's regional structure would have to address this structural problem.

My impression from interviewing WHO staff and health professionals outside the organisation is that the independent functioning of the regions is still getting in the way of WHO's effectiveness. The external review of Roll Back Malaria, for example, noted “an uneasy relationship between WHO headquarters and the regional offices,” particularly with the African regional office.13 Brundtland, say many WHO staff, managed to have closer working relationships with the regional directors but did nothing to challenge their long-held autonomy.

Too little, too late

Brundtland's senior staff say that her reform process has two phases. The first involved a shake up at headquarters. WHO is now entering the second phase—looking at the support it gives to countries.

At this year's World Health Assembly, in May 2002, Brundtland announced WHO's “country focus initiative,” which is aimed at strengthening WHO's presence at country level.24 But many WHO staff questioned why this initiative was so late in coming, and one asked whether it was just lip service. With a change of director general next year, phase two is surely now in jeopardy.

Gill Walt, professor of international health policy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, summed up the dilemma at the heart of the Brundtland term: “There's a huge gap between what's going on at the global level—such as new global partnerships—and what's happening at the country level, where they are struggling to deliver services and don't always know about these networked initiatives.”

A changing landscape

Brundtland's term coincided with a surge of interest in international health. Rich governments started talking about global health at the G8 summit in 1997. The Gates Foundation put $2.8bn into global health initiatives that are largely outside of WHO's governance. The Global Fund is a new public-private health funding mechanism, with its own governing body, that committed up to $616m in April this year to the prevention and treatment of AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.

The landscape of global health is changing, fragmenting into a huge array of new initiatives and alliances. Where does this leave WHO? This is a question that the organisation is still grappling with. Peter Piot, executive director of the joint United Nations programme on HIV and AIDS, believes that in the new global set up “WHO still has to look for its place in the world.”

Brundtland's legacy

Brundtland played a key role in restoring political interest in health. Her major contribution, said Piot, “will have been to put health on the international political agenda. That was her legacy.”

One way in which she raised the profile of health was through the report of the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health.25 Many of those I interviewed referred to this report as an outstanding piece of advocacy work, that made the compelling case that investing in health is vital for global economic development.

Brundtland stands down

One term is a brief period in the history of a huge UN bureaucracy, and so Brundtland's decision not to stand for a second term came as a shock. The reason she gave for not standing was that she would be 69 years old at the end of a second term.

I visited WHO's headquarters the week after her announcement. There was widespread speculation about whether there might have been other reasons for her departure, such as her increasing dislocation from her staff. There was a feeling that while she boosted staff morale when she took office, she squandered their initial enthusiasm by becoming increasingly isolated, uncommunicative, and hidden behind her cabinet. She also faced two huge pressures—mounting criticism of the World Health Report 2000 and difficulty in making any real change to WHO's troubled regional structure.

Conclusion

Brundtland injected a strong sense of direction into an ailing bureaucracy by focusing its efforts on a few priorities. Through high profile global health campaigns and the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, she put WHO back on the global map. Donor governments have a renewed confidence in WHO and have steadily increased their extrabudgetary donations.

But Brundtland's managerial changes have had a mixed reception from WHO staff, and she has failed to extend her reforms beyond headquarters. Her vision of “One WHO” has not yet been realised. There is still a dislocation between headquarters and the regions. The WHO continues to be funded by two distinct sources, and donors are still influencing how their donations are spent.

Brundtland recentralised WHO, concentrating its focus on Geneva. This tactic helped launch new alliances, such as Roll Back Malaria, but WHO is not comfortable in its partnership role and these alliances have not yet had a major impact on the world's poor.

Figure.

WHO's cluster structure at headquarters. Source: WHO

Figure.

WHO

Gro Brundtland restored WHO's credibility with donors

Figure.

WHO

WHO's Tobacco Free Initiative aims to curb the 4 million annual deaths caused by tobacco

Footnotes

This is the first of five articles

Competing interests: The BMJ receives submissions and commissions papers from many WHO authors, but GY is not involved in decisions about publication of these. GY now works for BMJ Unified, a joint venture between the BMJ Publishing Group and United HealthCare Services Inc (www.besttreatments.org)

References

- 1.Garrett L. Betrayal of trust: the collapse of global health. New York: Hyperion; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith R. The WHO: change or die. BMJ. 1995;310:543–544. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6979.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Report of the Executive Board Working Group on WHO response to global change. Executive Board 92nd session. Geneva: WHO; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaughn P, Walt G, Lee K, Møgedal S, Kruse S-E, de Wilde K, et al. Cooperation for health development: extrabudgetary funds in the World Health Organisation. Summary report. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas A, Møgedal S, Walt G, Steen SH, Kruse S-E, Lee K, et al. Cooperation for health development: WHO's support to programmes at country level. Summary. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frenk J, Sepúlveda J, Gómez-Dantés O, McGuinness MJ, Knaul F. The future of world health: the new world order and international health. BMJ. 1997;314:1404. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7091.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Mazrou Y, Berkley S, Bloom B, Chandiwana SK, Chen L, Chimbari M, et al. A vital opportunity for global health. Lancet. 1997;350:750–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Dr Gro Harlem Brundtland, Director-General Elect, The World Health Organization. Speech to the fifty-first World Health Assembly, Geneva, 13 May 1998. Geneva: WHO; 1998. www.who.int/director-general/speeches/1998/index.html (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. A corporate strategy for WHO secretariat. Report by the Director-General. Geneva: WHO; 1999. www.who.int/gb/EB_WHA/PDF/EB105/ee3.pdf (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor AL, Bettcher DW. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: a global “good” for public health. Bull World Health Org. 2000;78:920–929. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamey G. Global campaign to eradicate malaria. BMJ. 2001;322:1191–1192. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Roll Back Malaria. Geneva: WHO; 1999. www.who.int/gb/EB_WHA/PDF/EB103/ee6.pdf (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Achieving impact: Roll Back Malaria in the next phase. Final report of the external evaluation of Roll Back Malaria. August 29 2002. http://mosquito.who.int/cmc_upload/0/000/015/905/ee.pdf (accessed 18 Oct 2002).

- 14.World Bank. World development report 1993: investing in health. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbasi K. The World Bank and world health. BMJ. 1999;318:1003–1006. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7189.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand S, Hanson K. DALYs: efficiency versus equity. World Development. 1998;26:307–310. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Proposed programme budget 2002-2003. Geneva: WHO; 2001. www.who.int/gb/EB-WHA/E/E_docPB2002.htm (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. World health report 1999. Making a difference. Geneva: WHO; 1999. www.who.int/whr/1999 (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. World health report 2000. Health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO, 2000. www.who.int/whr/2000 (accessed 23 Oct 2002).

- 20.Williams A. Science or marketing at WHO? A commentary on “World Health 2000.”. Health Econ. 2001;10:93–100. doi: 10.1002/hec.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braveman P, Starfield B, Geiger HJ. World Health Report 2000: how it removes equity from the agenda for public health monitoring and policy. BMJ. 2001;323:678–681. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7314.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Health systems performance assessment. Report by the secretariat. Geneva: WHO; 2001. www.who.int/gb/EB-WHA/PDF/EB107/ee9.pdf (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gear HS. The World Health Organisation. New York Conference, 1946. South African Medical Journal. 1946;20:515–517. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Improving WHO performance at country level: “The Country Focus Initiative.” Consultation draft. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. Geneva: WHO; 2001. www.cid.harvard.edu/cidcmh/CMHReport.pdf (accessed 23 Oct 2002). [Google Scholar]