Summary

Background

In children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) tuberculosis is common, challenging to diagnose, and often fatal. We developed tuberculosis treatment decision algorithms (TDAs) for children under the age of 5 years with SAM.

Methods

In this prospective diagnostic study, we enrolled and followed up children aged <60 months hospitalised with SAM at three tertiary hospitals in Zambia and Uganda from 4 November 2019 to 20 June 2022. We included children aged 2–59 months with SAM as defined by WHO and hospitalised following the WHO clinical criteria. We excluded children with current or history of antituberculosis treatment within the preceding 3 months. They underwent tuberculosis symptom screening, clinical assessment, chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasound, Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Ultra) and culture on respiratory and stool samples with 6 months follow-up. Tuberculosis was retrospectively defined using the 2015 standard case definition for childhood tuberculosis. We used logistic regression to develop diagnostic prediction models for a one-step diagnosis and a two-step screening and diagnostic approaches. We derived scores from models using WHO-recommended thresholds for sensitivity and proposed TDAs. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04240990.

Findings

Of 1906 children hospitalised with SAM during the study period, 1230 were screened, 1152 were eligible and 603 were enrolled. Of the 603 children enrolled–median age 15 (inter-quartile range (IQR): 11–20) months and 65 (11.0%) living with HIV–114 (18.9%) were diagnosed with tuberculosis, including 51 (8.5%) with microbiological confirmation and 104 (17.2%) initiated treatment at a median of 6(IQR: 2–10) days after inclusion. 108 children were retrospectively classified as having tuberculosis resulting in a prevalence of 17.9% (95% confidence intervals (CI): 15.1; 21.2). 75 (69.4%) children with tuberculosis reported cough of any duration, 32 (29.6%) cough ≥2 weeks and 11 (10.2%) tuberculosis contact history. 535 children had complete data and were included in the diagnostic prediction model. The one-step diagnostic model had 15 predictors, including Ultra, clinical, radiographic, and abdominal features, an area under the receiving operating curve (AUROC) of 0.910, and derived TDA sensitivity of 86.14% (95% CI: 78.07–91.56) and specificity of 80.88% (95% CI: 76.91–84.30). The two-step model had AUROCs of 0.750 and 0.912 for screening and diagnosis, respectively, and derived combined TDA sensitivity of 79.21% (95% CI: 70.30–85.98) and a specificity of 83.64% (95% CI: 79.87–86.82).

Interpretation

Tuberculosis prevalence was high among hospitalised children with SAM, with atypical clinical features. TDAs achieved satisfactory diagnostic accuracy and could be used to improve diagnosis in this vulnerable group.

Funding

Unitaid.

Keywords: Severe acute malnutrition, Tuberculosis, Treatment decision algorithms, Diagnosis, Children

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched Pubmed using the following search terms: (“child∗” OR “paediatr∗” OR “pediatr∗”) AND (“tuberculosis” OR “TB”) AND (“treatment-decision” OR “algorithm” OR “diagnos∗”) AND (“malnutrition” OR “undernutrition”) to identify primary research studies on childhood pulmonary tuberculosis in children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and use of treatment decision algorithms (TDA) or scoring systems published in any language before 27th August 2023. We found limited data on the burden of tuberculosis in children and a recognition of the limitations of existing diagnostic approaches to identify tuberculosis in children with SAM. While data driven TDAs have been suggested for the identification of tuberculosis in the general pediatric population and for CLHW, no specific tools are available that address the unique needs of children with SAM.

Added value of this study

This study brings important new evidence showing a high prevalence of tuberculosis among hospitalized children with SAM in Uganda and Zambia with high rates of microbiological confirmation. Many children presented without the typical tuberculosis clinical features but with an atypical pneumonia-like presentation. We propose two TDAs including a 1) one-step diagnostic approach, and 2) a two-step screening and diagnostic approach, with sensitivities ranging 77%–86% and specificities 81%–86% to guide tuberculosis treatment decision making in children with SAM. Conventional biomarkers such as CRP, Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR), and haemoglobin count did not contribute to improved screening, which calls for other screening biomarkers in this population.

Implications of all the available evidence

The study provides further evidence of the high prevalence of tuberculosis in hospitalised children with SAM and that the traditional clinical approach might be insufficient for case finding. Systematic screening approaches should be applied to identify tuberculosis in children with SAM, including those with acute pneumonia presentations, taking into consideration health economics aspects and costs. WHO conditionally recommended incorporating TDAs, subject to validation, into existing case detection strategies to facilitate the decentralization of clinical tools and enable easier identification of tuberculosis in children. In children hospitalised with SAM, the two proposed TDAs developed by this study have satisfactory diagnostic accuracy and could be used to improve the identification of tuberculosis in this vulnerable key risk group. Approaches for children with moderate acute malnutrition or those with SAM managed in ambulatory settings warrant further research, as does feasibility, acceptability, and impact on case detection and mortality of TDAs overall.

Introduction

Tuberculosis and severe acute malnutrition (SAM) are important causes of morbidity and mortality in children from low-income countries. An estimated 1.3 million children and young adolescents ≤15 years develop tuberculosis and almost a quarter of them die each year; mostly undiagnosed and untreated.1,2 About 45 million young children (<5 years) were affected by wasting in 2022; 13.7 million with “severe” wasting - and almost 50% of the children who die aged <5 years have undernutrition.3,4 SAM, the most severe manifestation of undernutrition, is characterised by severe wasting with or without nutritional oedema.5 It is increasingly recognised that young children with SAM are an important risk group for the development of tuberculosis.6, 7, 8 The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that undernutrition contributes to 20% of all tuberculosis cases globally although the exact burden of tuberculosis in children with SAM is not well defined.1,8,9 Improving case detection in children with SAM could contribute to reducing mortality and is essential to achieving the global goal of zero deaths from tuberculosis in children.6,7

Tuberculosis and SAM share a complex bidirectional relationship regarding epidemiology and clinical management. Both conditions are poverty related. Malnutrition significantly weakens both innate and adaptive immune responses, resulting in heightened vulnerability to tuberculosis after contracting mycobacterial infection. Conversely, children with tuberculosis are susceptible to developing wasting, as tuberculosis exerts catabolic effects on the body. This creates a vicious cycle, perpetuating the detrimental interaction between these two conditions.10, 11, 12, 13 Furthermore, the diagnostic challenges that characterize tuberculosis in children are compounded in the presence of SAM. The clinical signs and symptoms, such as weight loss or lethargy, overlap significantly. Radiological features are non-specific, while microbiological tests perform poorly due the paucibacillary nature of pulmonary tuberculosis in immunocompromised individuals.8,14,15 In practice, diagnosis of tuberculosis in children with SAM is often only considered when there is poor response to nutritional rehabilitation. All these factors contribute to under-detection or diagnostic delays and increase the risk of mortality or poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes.14,16,17

Treatment decision algorithms (TDA) are diagnostic tools that aim to accelerate the identification of tuberculosis in children and could play a crucial role in bridging the persistent child tuberculosis case detection gap particularly in key risk groups that are often difficult to diagnose. As other scoring systems, they combine specific clinical, radiological and microbiological features to arrive at a composite score that is predictive of tuberculosis.18 The WHO recently recommended the use of integrated TDAs for tuberculosis diagnosis in children and provided two options that can be adapted for use in settings with and without access to chest radiography.19 However, no TDA has been specifically developed or evaluated for the highly vulnerable group of children with SAM, as was done previously for children living with HIV (CLWH).20

We hypothesized that a specific prediction score will improve tuberculosis diagnosis in children hospitalised with SAM. We aimed to develop a diagnostic prediction score that could result in a TDA for tuberculosis in children hospitalised with SAM.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a prospective diagnostic cohort study in three tertiary hospitals: the University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka and Arthur Davidson Children's Hospital, Ndola in Zambia and Mulago National Referral Hospital in Kampala in Uganda. From 4 November 2019 to 20 June 2022, we enrolled and followed up children with the following inclusion criteria: being aged 2–59 months, hospitalised for SAM as defined by the WHO; weight-for-height Z score (WHZ) <−3 standard deviation (SD) or mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) <115 mm (in children over 6 months) or bilateral pitting oedema. WHO clinical criteria for hospitalisation with SAM included: poor appetite or presence of any danger signs (vomiting, convulsions, lethargy or reduced level of consciousness) categorised as SAM with medical complications.5 We excluded children with current or history of antituberculosis treatment within the preceding 3 months. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians. This study followed the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) reporting guidelines.

The study was approved by the sponsor's (Inserm) institutional review committee, the WHO ethical review committee, as well as the national ethics committees and institutional review boards in Uganda and Zambia (Appendix). This study is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04240990).

Procedures

At inclusion, history of tuberculosis (including tuberculosis contact) was obtained from the parent or guardian followed by a complete physical examination and malnutrition assessment. Tuberculosis evaluation, HIV and malaria testing, and blood sampling for full blood count, transaminases, C-reactive protein (CRP) and interferon gamma release assay QuantiFERON®-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were performed. The monocyte-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) was calculated. In infants exposed to HIV, HIV-DNA PCR or nucleic acid testing were performed according to early-infant-diagnosis guidelines in Zambia and Uganda at the time of the study.

Microbiological tests included the molecular Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Xpert Ultra; Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) assay performed on one sample each of nasopharyngeal aspirate, stool sample and gastric aspirate, and mycobacterial culture on two gastric aspirates. Stool samples were processed using sucrose flotation before Xpert Ultra testing.21 Anteroposterior and lateral view chest x-rays (CXR) were used to assess for predefined radiological features suggestive of tuberculosis by experienced attending physician.22 Abdominal ultrasonography (AUS) was performed to assess for the presence of abdominal lymphadenopathy, splenic micro-abscesses, as well as hepatic abscesses, and peritoneal effusion. Although the primary focus was on the abdomen the sonographer was required to report on the presence of thoracic and pericardial effusion as well. AUS were performed by trained radiology technologist using fixed sonography equipment.

The tuberculosis diagnosis work-up was completed within 1–3 days of hospitalisation and antituberculosis treatment initiated when tuberculosis was diagnosed. All children were followed-up on days 15 and months 1, 2, 3 and 6. At each visit, a clinical evaluation was conducted to document; adverse events, adherence, nutritional recovery, and symptoms resolution. Tuberculosis evaluation was repeated when clinically indicated. Chest radiographs were repeated at the two- and six-month visits. Children received care and treatment according to the WHO recommendations for hospitalised children with SAM5 and tuberculosis was managed in accordance with national tuberculosis guidelines. Antiretroviral treatment was initiated in CLWH if not on treatment.

At the end of the study, children were retrospectively classified as having confirmed, unconfirmed or unlikely tuberculosis using the updated NIH Clinical Case Definition23 by an endpoint review committee (ERC) established in each country. They reviewed i) clinically diagnosed tuberculosis cases; ii) differential diagnoses made in children not clinically improving at month 2; iii) all deaths and ongoing diseases at time of death for causality.

During the COVID-19 pandemic country lockdowns (April–October 2020), follow-up was conducted by phone when physical visits were not possible. The safety of staff and children/families were ensured at the study visits, sample collection and processing in the respective laboratories.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic prediction scores and associated TDAs that were developed, defined as either confirmed or unconfirmed tuberculosis. The secondary outcomes included: prevalence of tuberculosis (microbiologically confirmed and unconfirmed) among children with SAM; estimated time to antituberculosis initiation; diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive value) of the different tests and the area under the receiving operating curve (AUROC) of diagnostic prediction models with and without the different tests results.

Statistical analysis

We assumed a tuberculosis prevalence of 15% among children with SAM8 and estimated that enrolling approximately 720 children would enable development of a diagnostic prediction model with an expected sensitivity of 80%, a minimal acceptable lower sensitivity of 65%, with 10% missing data on key predictors. Our hypothesis was that a specific prediction score will improve tuberculosis diagnosis in children hospitalised with SAM. Study recruitment was concluded when 603 participants were enrolled by December 2021 following discussions with the Scientific Advisory Board on feasibility/budgetary issues and as the main study hypothesis seemed verified pre-hoc based on antituberculosis treatment initiated in the study.

We determined the prevalence of tuberculosis in the study population in each participating country. Comparisons of clinical and laboratory characteristics (by tuberculosis status) were done using Kruskal–Wallis, Pearson's chi-squared and Wilcoxon tests, as appropriate.

We developed tuberculosis diagnostic prediction models and scores using logistic regression with two approaches. First, we developed a one-step full diagnostic prediction model where all available clinical details and diagnostic tests were applied to all the participants. Second, aiming to reduce costs and sample collection, we developed a 2-step approach with a screening model to identify children who would benefit from further diagnostic testing, i.e., with “presumptive tuberculosis”, in which Ultra results, abdominal ultrasound, and CXR were excluded from model development, and a second diagnostic model for children with presumptive tuberculosis. We used similar modelling and score development methods previously used for two specific diagnostic scores in children with and without HIV.20,24 Briefly, we identified candidate predictors from literature and previous tuberculosis childhood scoring systems and algorithms, and from a nested case–control analysis using those with microbiologically-confirmed tuberculosis as cases and children who were alive at month 6 and who did not receive antituberculosis treatment as controls. We entered all chosen variables, in logistic regression model, restricting the analysis to children with complete data for the chosen predictors. We obtained final models by backward stepwise selection using Akaike's criteria25,26 and we included Xpert Ultra results secondarily.27 We assessed the predictive performance of the models using the AUROC statistic. We assessed the added value of haemoglobin, MLR, and CRP in screening and diagnosis models.

We selected predicted probability cut-offs reaching a sensitivity of 85% and 90% or above diagnostic- and screening models respectively. We developed associated diagnostic scores with a threshold of 10 to facilitate calculations (see Supplementary methods) and estimated their final diagnostic accuracy.28 Post-hoc, we developed diagnostic scores without abdominal ultrasound and compared their diagnostic performance with that of the main scores. We also performed a post-hoc sensitivity analysis of the score performances considering as unconfirmed tuberculosis, children that were classified as unlikely tuberculosis with unknown end of study status (withdrawn, lost-to-follow-up or transferred out) and had a follow-up time of less than a month or did not show improvement on either their nutritional status or tuberculosis symptoms. We finally incorporated scores in stepwise TDAs to guide practical implementation of the screening and diagnosis process. We assessed the performance of the scores in hypothetical populations of 1000 children with SAM with different tuberculosis prevalence rates. We performed internal validation using bootstrap resampling on 1000 replications to assess the model optimism and optimism-corrected AUROC. All statistical analyses were performed with R software version 4.1.2 or above and SAS 9.4.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. CC, OM, CR, MHN, EW and MB had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Of 1906 children hospitalised with SAM during the study period, 603 were enrolled (Fig. 1); median age (IQR) of 15.0 (11.0; 20.0) months, 345 (57.2%) male, and 65 (11.0%) CLHIV (Table 1). Overall, 337 (55.9%) children reported a cough (101 (16.7%) of ≥2 weeks duration); and 20 (3.3%) had a history of tuberculosis household contact. Of 575 children with CXR available, 264 (45.9%) had lesions suggestive of tuberculosis.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the study. The figures represent the flow of children from admission to enrolment in the study, the tuberculosis diagnosis classification by the clinician and the reclassification by the Endpoint Review Committee. ERC, endpoint review committee; TB, tuberculosis; ∗Common reasons were: the child conditions worsened requiring urgent medical management, died before completion of informed consent process, languages barriers, consent decision awaiting another family member (usually father) who was not available.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children enrolled (all, tuberculosis, not tuberculosis).

| N if differs from N′ | All children N′ = 603 | N if differs from N′ | Not TB N’ = 495 | N if differs from N′ | TB N’ = 108 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 345 (57.2) | 284 (57.4) | 61 (56.5) | 0.866 | |||

| Age (months) | 15.0 [11.0; 20.0] | 15.0 [10.0; 20.0] | 15.0 [11.0; 20.0] | 0.651 | |||

| Country | 0.033 | ||||||

| Uganda | 335 (55.6) | 282 (57.6) | 50 (46.3) | ||||

| Zambia | 268 (44.4) | 210 (42.4) | 58 (53.7) | ||||

| HIV positive | 589 | 65 (11.0) | 482 | 43 (8.9) | 107 | 22 (20.6) | 0.0005 |

| ART naïve (in children with HIV) | 65 | 50 (76.9) | 43 | 33 (76.7) | 22 | 17 (77.3) | 0.962 |

| History of TB contact | 20 (3.3) | 9 (1.8) | 11 (10.2) | 0.001 | |||

| Presence of oedema | 602 | 343 (56.9) | 491 | 274 (55.4) | 69 (63.9) | 0.109 | |

| Weight-for-height Z score | 601 | −3.3 [−4.2, −2.3] | 493 | −3.3 [−4.1, −2.2] | −3.3 [−4.3, −2.4] | 0.456 | |

| Cough any duration | 337 (55.9) | 262 (52.9) | 75 (69.4) | 0.002 | |||

| Cough >2 weeks | 101 (16.7) | 69 (13.9) | 32 (29.6) | 0.0001 | |||

| Fever >2 weeks | 72 (11.9) | 50 (10.1) | 22 (20.4) | 0.003 | |||

| Weight loss >2 weeks | 371 (61.5) | 300 (60.6) | 71 (65.7) | 0.320 | |||

| Fatigue or loss of playfulness >2 weeks | 266 (44.1) | 201 (40.6) | 65 (60.2) | 0.0002 | |||

| Signs of respiratory distressa | 80 (13.3) | 54 (10.9) | 26 (24.1) | 0.0003 | |||

| Depressed level of consciousnessb | 600 | 296 (49.3) | 493 | 230 (46.7) | 107 | 66 (61.7) | 0.005 |

| Peripheral O2 saturation (%) | 100 [99.0; 100] | 495 | 100 [99.0; 100] | 100 [99.0; 100] | 0.130 | ||

| Haemoglobin g/dL | 520 | 8.9 [7.6, 10.2] | 429 | 9.1 [7.7, 10.3] | 91 | 8.5 [7.0, 9.7] | 0.010 |

| Monocyte Lymphocyte Ratio | 488 | 0.2 [0.1, 0.3] | 399 | 0.2 [0.1, 0.3] | 89 | 0.2 [0.1, 0.3] | 0.228 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/L) | 479 | 2.5 [2.5, 6.4] | 397 | 2.5 [2.5, 6.1] | 82 | 2.5 [2.5, 12.1] | 0.308 |

| QFT result | 238 | 186 | 52 | 0.004 | |||

| Positive | 17 (2.8) | 8 (4.3) | 9 (17.3) | ||||

| Indeterminate | 121 (50.8) | 100 (53.8) | 21 (40.4) | ||||

| ALT (UI/L) | 455 | 36.0 [22.0, 60.5] | 379 | 37.0 [22.0, 61.0] | 76 | 32.0 [20.8, 54.3] | 0.617 |

| Hepatomegaly | 87 (14.4) | 60 (12.1) | 27 (25.0) | 0.0006 | |||

| Cervical or supra-clavicular adenopathies | 9 (1.5) | 4 (0.8) | 5 (4.6) | 0.003 | |||

| Chest X-ray lesions suggestive of TBc | 575 | 264 (45.9) | 469 | 193 (41.2) | 106 | 71 (67.0) | <0.0001 |

| Culture-confirmed TB | 556 | 16 (2.9) | 460 | 0 | 96 | 16 (16.7) | <0.0001 |

| Xpert Ultra positive | 596 | 44 (7.3) | 488 | 0 | 44 (40.7) | <0.0001 | |

| TB treatment initiation | 104 (17.2) | 14 (2.8) | 90 (83.3) | <0.0001 | |||

| Time to TB treatment (in days) | 104 | 6.0 [2.0, 10.0] | 14 | 10.0 [3.25, 27.5] | 90 | 6.0 [2.0, 9.0] | 0.095 |

| Final status | 0.156 | ||||||

| Alive | 422 (70.0) | 352 (71.1) | 70 (64.8) | ||||

| Dead | 80 (13.3) | 58 (11.7) | 22 (20.4) | ||||

| Transfer out | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0 | ||||

| Withdrawn | 39 (6.5) | 34 (6.9) | 5 (4.6) | ||||

| Lost to follow-up | 60 (10.0) | 49 (9.9) | 11 (10.2) |

Signs of respiratory distress: presence of ≥1 of the the following: grunting, nasal flaring, severe or very severe chest indrawing.

Depressed level of consciousness: Restless, irritable or Lethargic or unconscious.

Chest X-ray lesions suggestive of TB: presence of of ≥1 of the the following: miliary, alveolar, hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy, excavation (cavity), airway compression, pleural effusion. QTF, QuantiFERON Tb Gold In-Tube; TB, tuberculosis; ALT, alanine transaminase.

Fifty-one (8.5%) children had microbiologically confirmed and 63 (10.4%) clinically diagnosed tuberculosis (Fig. 1). Overall, 104 (17.2%) children initiated antituberculosis treatment at a median of 6 (2; 10) days. Eighty (13.3%) children died during the study, including 5 (6.3%) with confirmed- 17 (21.3%), unconfirmed- and 58 (72.5%) no tuberculosis (Table 1) (Appendix Table S1). No case of drug-resistant TB was diagnosed by culture in this cohort of children. Only 1 child had rifampicin resistance detected by Xpert on GA sample; treatment was refused by the caregiver.

The ERC reclassified 15/63 (23.8%) children with unconfirmed-as unlikely tuberculosis, and 9/58 (15.5%) who died and were considered unlikely-as unconfirmed tuberculosis. By final ERC classification, 51 (8.5%) children had confirmed- and 57 (9.5%) unconfirmed tuberculosis (Fig. 1). The overall prevalence of tuberculosis was 17.9% (108/603 (95% CI: 15.5; 21.7)); 14.9% (50/335 [95% CI: 11.5; 19.1)) in Uganda and 21.6% (58/268; (95% CI: 17.1; 27.0)) in Zambia, with microbiological confirmation rates of 10.5% and 6.0%, respectively.

Among 108 children with tuberculosis, 22 (20.4%) had fever ≥2 weeks, 32 (29.6%) cough ≥2 weeks and 11 (10.2%) a history of household tuberculosis contact (Table 1). The proportion of CLHIV was higher in children with tuberculosis compared to those without tuberculosis (20.6% vs 8.9%, p = 0.0005). QFT were positive in 9/52 (17.3%) children with tuberculosis tested and 8/186 (4.3%) children without tuberculosis, with 40.4% and 53.8% indeterminate results in each group, respectively. Among children with tuberculosis, 16/96 (16.7%) had a positive culture result and 44/108 (40.7%) had a positive Xpert Ultra result on any sample, including 21/41 (51.2%) with “trace” results (Appendix Table S1).

None of the signs, symptoms and diagnostic tests identified as candidate predictors had both satisfying sensitivity and specificity (Appendix Table S2). Signs with the best sensitivity (>60%) for tuberculosis diagnosis were fever and cough of any duration, fatigue or loss of playfulness, weight loss, and loss of appetite but sensitivity decreased when using sign duration ≥2 weeks yet their specificity increased.

The final one-step diagnostic prediction model was developed in 535 children with complete data for all selected clinical, microbiological (Xpert Ultra), ultrasonographic and radiological predictors. There was no difference on selected predictors between the children with and without complete data (Appendix Table S3). The model included 15 predictors with Xpert Ultra, with an AUROC of 0.910 (optimism-corrected AUROC 0.885; 95% CI: 0.885–0.886, Appendix Table S10) (Table 2 & Fig. 2). Adding MLR, CRP, and haemoglobin to the model did not improve the AUROC and none of these predictors remained in the final model (Appendix Table S4 and Figure S2). We selected a cut-off on the ROC curve giving a sensitivity of 86.14% (95% CI: 78.07–91.56) and a specificity of 80.88% (95% CI: 76.91–84.30) for the detection of tuberculosis.

Table 2.

One-step diagnostic prediction model.

| Multivariate analysis (N = 535) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Xpert result positive | 1037.7 | [130.8; 134524.3] | 0.000 |

| Contact with an adult who had TB | 5.4 | [1.1; 22.5] | 0.044 |

| Cough >3 weeks | 3.2 | [1.4; 7.2] | 0.006 |

| Loss of appetite >2 weeks | 1.5 | [0.8; 3.0] | 0.216 |

| Tachycardia | 3.4 | [1.5; 7.6] | 0.004 |

| Chest indrawing | 4.2 | [1.7; 10.0] | 0.002 |

| Depressed level of consciousness | 1.2 | [0.6; 2.2] | 0.643 |

| CXR Aveolar opacity | 2.4 | [1.2; 4.7] | 0.011 |

| CXR Hilar mediastinal lymphadenopathy | 3.4 | [1.8; 6.7] | 0.0002 |

| CXR Pleural effusion | 8.9 | [1.6; 96.5] | 0.013 |

| CXR Pericardial effusion | 0.2 | [0.01; 2.2] | 0.196 |

| AUS Splenic micro abscesses | 5.4 | [1.5; 18.4] | 0.010 |

| AUS Hepatic micro abscesses | 8.1 | [0.6; 75.0] | 0.102 |

| AUS Pericardial or pleural effusion | 1.9 | [0.7; 4.8] | 0.222 |

| AUS Peritoneal effusion - ascites | 1.3 | [0.3; 4.8] | 0.734 |

CXR, Chest x-ray; AUS, Abdominal Ultrasound; aOR, adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and proposed diagnostic threshold of the one-step TB diagnostic prediction model. The final one-step diagnostic prediction model had an AUROC of 0.910. A cut-off giving a sensitivity of 86.14% and a specificity of 80.88% on the ROC curve was selected for the detection of tuberculosis. Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; AUC, area under the curve.

In the two-step approach, the final screening model included 10 predictors with an AUROC of 0.750 (0.723; 95% CI: 0.722–0.724, Appendix Table S10) (Fig. 3A & Table 3). Adding MLR, CRP, and haemoglobin in the model did not increase the AUROC and none of these parameters remained in the model. We selected a threshold with a sensitivity of 89.11% (95% CI: 81.54–93.81) and a specificity of 34.79% (95% CI: 30.46–39.39), which identified 373 children with presumptive tuberculosis, missing 11 children with tuberculosis. The final full diagnostic model developed in those 373 children included 13 predictors with Xpert Ultra, with an AUROC of 0.912 (0.877; 95% CI: 0.876–0.878, Appendix Table S10). We selected a predicted probability cut-off with a sensitivity of 88.89% (95% CI: 80.74–93.85) and a specificity of 74.91% (95% CI: 69.55–79.61) on the 373 presumptive children (Fig. 3B), for an overall sensitivity of 79.21% (95% CI: 70.30–85.98) and a specificity of 83.64% (95% CI: 79.87–86.82) for tuberculosis detection of the two-step approach.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and proposed decision thresholds for the (A) First-step screening prediction model (B) Second-step diagnostic prediction model. In the two-step approach, in the final screening model (A) we selected a cut-off giving a sensitivity of 89.11% and a specificity of 34.79%, in the second step diagnostic prediction model we selected a predicted probability cut-off with a sensitivity of 88.89% and a specificity of 74.91%. Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; AUC, area under the curve.

Table 3.

Two-step TB diagnostic prediction models.

| Multivariate 1st step screening model without CXR, AUS, Xpert (N = 535) |

Multivariate 2nd step diagnostic model with CXR, AUS, Xpert (N = 373) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Contact with an adult who had TB | 5.3 | [1.7; 16.2] | 0.004 | 5.4 | [0.01; 0.05] | 0.000 |

| Fatigue >2 weeks | 1.5 | [0.9; 2.5] | 0.037 | / | / | / |

| Cough >3 weeks | 2.4 | [1.2; 4.5] | 0.009 | 2.9 | [1.3; 7.0] | 0.013 |

| Temperature >38 °Ca | 4.1 | [1.5; 11.3] | 0.006 | / | / | / |

| Tachycardia | 1.7 | [0.8; 3.5] | 0.136 | 3.3 | [1.4; 7.7] | 0.007 |

| Chest indrawing | 2.2 | [1.0; 4.9] | 0.058 | 4.2 | [1.7; 10.3] | 0.002 |

| Crackles on auscultation | 2.2 | [1.1; 4.2] | 0.018 | / | / | / |

| Depressed level of consciousness | 1.6 | [1.0; 2.8] | 0.059 | / | / | / |

| Cervical or supra clavicular adenopathy | 3.9 | [0.7; 21.1] | 0.113 | / | / | / |

| HIV infection | 1.8 | [0.9; 3.4] | 0.098 | / | / | / |

| Loss of appetite >2 weeks | / | / | / | 1.6 | [0.8; 3.5] | 0.207 |

| Xpert result positive | / | / | / | 902.1 | [108.6; 118338.0] | 0.000 |

| CXR Alveolar opacity | / | / | / | 2.9 | [1.4; 6.1] | 0.004 |

| CXR Hilar mediastinal lymphadenopathy | / | / | / | 2.8 | [1.3; 5.8] | 0.006 |

| CXR Pleural effusion | / | / | / | 8.6 | [1.5; 90.3] | 0.015 |

| CXR Pericardial effusion | / | / | / | 0.3 | [0.01; 2.6] | 0.253 |

| AUS Splenic micro abscesses | / | / | / | 3.7 | [0.8; 16.5] | 0.097 |

| AUS Hepatic micro abscesses | / | / | / | 9.1 | [0.7; 83.5] | 0.088 |

| AUS Pericardial or pleural effusion | / | / | / | 2.4 | [0.9; 6.4] | 0.090 |

CXR, Chest x-ray; AUS, Abdominal Ultrasound; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

Temperature reading at study enrolment.

The one-step diagnostic prediction model developed post-hoc without abdominal ultrasound had an AUROC of 0.904 (0.872; 95% CI: 0.872–0.873, Appendix Table S10), 13 predictors and the derived score had a sensitivity and a specificity of 85.15% (95% CI: 76.93–90.79) and 79.26% (95% CI: 75.20–82.81) respectively (Appendix Table S7 and Figure S3), with no significant difference with the main one-step diagnostic score, neither for sensitivity (Mc Nemar p > 0.99) nor for specificity (Mc Nemar p = 0.178) (Appendix Table S9). Considering as unconfirmed 46 of 101 children with unlikely tuberculosis and unknown end of study status, the sensitivity and specificity were respectively 66.67% (95% CI: 58.71–73.78) and 81.44% (95% CI: 77.27–85) for the one-step diagnosis model, and 61.22% (95% CI: 53.16–68.72) and 84.28% (95% CI: 80.32–87.56) for the diagnosis model in the two-step approach.

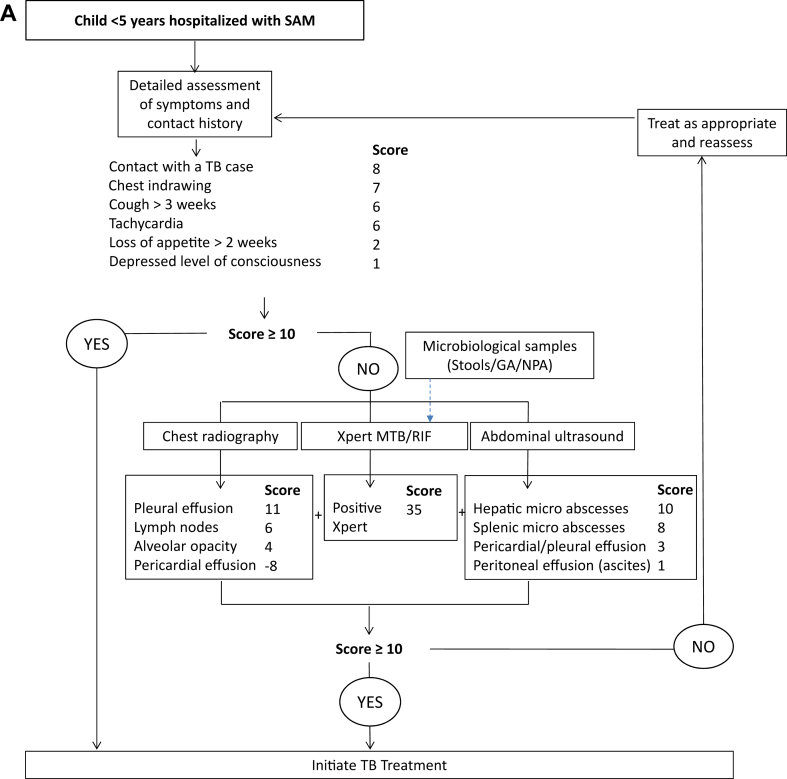

The diagnostic scores and proposed TDAs are presented in Appendix Tables S5 and S6 and in Fig. 4. In the one-step TDA, all children should undergo full diagnostic evaluation and a score ≥10 at any level should prompt antituberculosis treatment initiation (Fig. 4A). In the two-step TDA, every child screened positive for ≥1 among 9 criteria will be considered as presumptive tuberculosis and will undergo full diagnostic evaluation (Fig. 4B). The performance of the two TDAs in a population of 1000 children with varying tuberculosis prevalence rates is shown in Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Proposed treatment decision algorithms: (A) ‘one step’ and (B) ‘two steps’ diagnostic approaches. TB, tuberculosis; SAM, Severe acute malnutrition; NPA, Nasopharyngeal aspirate; GA, gastric aspirate. The total score in each figure is the sum of each individual score from history, microbiological tests, Chest x-ray and ultrasound.

Table 4.

Diagnostic performances of the proposed TDAs in 1000 children under 5 years hospitalized with severe acute malnutrition with different tuberculosis prevalence rates.

| Tuberculosis prevalence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic approaches | 5% | 10% | 14.9%a | 17.9%b | 21.6%c |

| One-step algorithm (Sensitivity = 86.1%; Specificity = 80.9%) | |||||

| True positives (TB correctly diagnosed) | 43 | 86 | 128 | 154 | 186 |

| False positives (overdiagnosed with TB) | 181 | 172 | 163 | 157 | 150 |

| True negatives (TB correctly ruled-out) | 769 | 728 | 688 | 664 | 634 |

| False negatives (missed TB cases) | 7 | 14 | 21 | 25 | 30 |

| Screening phase algorithm (Sensitivity = 89.1%; Specificity = 34.8%) | |||||

| True positives (TB correctly identified as presumptive TB)d | 45 | 89 | 133 | 159 | 192 |

| False positives (overdiagnosed with presumptive TB)d | 619 | 587 | 555 | 535 | 511 |

| True negatives (TB correctly ruled-out) | 331 | 313 | 296 | 286 | 273 |

| False negatives (missed TB cases) | 5 | 11 | 16 | 20 | 24 |

| Final diagnosis with screening and diagnosis algorithm (Sensitivity = 79.2%; Specificity = 83.6%) | |||||

| True positives (TB correctly diagnosed) | 40 | 79 | 118 | 142 | 171 |

| False positives (overdiagnosed with TB) | 156 | 148 | 140 | 135 | 129 |

| True negatives (TB correctly ruled-out) | 794 | 752 | 711 | 686 | 655 |

| False negatives (missed TB cases) | 10 | 21 | 31 | 37 | 45 |

TB, tuberculosis.

Prevalence of TB in Uganda according to our study results.

Prevalence of TB in our study.

Prevalence of TB in Zambia according to our study results.

Only children identified as presumptive tuberculosis i.e. true and false positive will have full diagnostic assessment.

Discussion

This study brings important new evidence on tuberculosis in children with SAM. We report a high tuberculosis prevalence in hospitalised children with SAM in Uganda and Zambia with high rates of microbiological confirmation. We have developed two TDAs with sensitivities ranging 77%–86% and specificities 81%–86% to guide clinical decision making in highly vulnerable population where traditional diagnostic approaches have limitations.

The two proposed TDAs had satisfying diagnostic performances comparable to the WHO suggested TDAs (86% sensitivity and 37% specificity) and could significantly aid the identification of tuberculosis in hospitalised children with SAM. We set our sensitivity at 85%, as the WHO-suggested TDAs, but we included molecular diagnosis in the model itself to improve its discriminative performance. Our one-step TDA could hence outperform the WHO-suggested TDAs for children with presumptive pulmonary tuberculosis, that have not been tested in this population.29 The lower specificity of the screening step of our two-step algorithm suggests that more children would be subjected to diagnostic work-up than needed; however, this step could reduce costs and burden of sample collection and diagnostic tests in a significant proportion of children. The one-step TDA correctly diagnoses more children with tuberculosis but results in higher risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment compared to the two-step TDA. The choice of the approach to use should take into consideration local tuberculosis epidemiology and health service costs.

Our study confirms high tuberculosis prevalence rates reported previously in children with SAM in tertiary hospitals. These studies, heterogeneous in sample size and approaches, reported wide ranging prevalence of tuberculosis from 0.4% with microbiologic diagnosis in Zambia up to 44% initiated on tuberculosis treatment in Malawi.15 Our study provides a rigorous assessment of the burden of tuberculosis in children hospitalised with SAM, demonstrating that tuberculosis affects about one in every five patients with similar proportions in Uganda and Zambia. The systematic molecular tuberculosis screening on admission yielded almost 50% microbiological confirmation among children diagnosed with tuberculosis, much higher than previous studies in hospitalised children with SAM in Malawi, Mozambique, and Bangladesh, using generic Xpert or mycobacterial cultures.14,15,30 Interestingly, our microbiological confirmation rate was much higher on Xpert Ultra than on culture, with more than half positive Xpert Ultra being trace results.

As expected, a large proportion of tuberculosis cases were nonetheless diagnosed clinically, reflecting the poor sensitivity of existing tools for identifying childhood tuberculosis cases. A significant proportion of children diagnosed with tuberculosis did not exhibit the typical chronic tuberculosis suggestive symptoms.19 Less than one-third found with tuberculosis reported coughing ≥2 weeks, and even fewer reported a history of fever, likely due to the blunting of symptoms commonly observed in children with SAM and impaired immune responses.8 Symptoms were acute and consistent with pneumonia, which supports the findings that tuberculosis is prevalent among children with SAM presenting with pneumonia and that systematic approaches are required in this group in high tuberculosis incidence countries.31 Both diagnostic- and the screening scores included chest indrawing, a sign of pneumonia used in Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses approach. Additionally, our screening score included crackles, an auscultation sign associated with pneumonia. Chest X-ray lesions suggestive of tuberculosis were reported in two thirds of the patients with alveolar opacities, lymph nodes, pleural and pericardial effusion independently predictive of tuberculosis.

Interestingly, laboratory tests like haemoglobin, CRP and MLR did not improve model discrimination for either screening or diagnosis, which calls for other screening biomarkers in this population. Surprisingly, AUS features included in the models did not include abdominal lymph nodes, that were previously identified as associated with tuberculosis diagnosis, but strongly contributed to their discriminative performance.20,32, Using point-of-care-ultrasonography (POCUS), a study among hospitalised Malawian children with SAM could not establish ultrasonographic features linked to the diagnosis of tuberculosis.33 Furthermore, despite improving the performance of clinical models without Ultra (results not shown), AUS did not have significant added value in the diagnostic algorithms.

The imaging findings highlight a notable aspect; when clinicians identified pericardial effusion through CXR, it was associated with a lower risk of TB and contributed to a negative score in the TDAs. Conversely, the presence of pleural and pericardial effusion, which could be more accurately detected through ultrasound examinations but were reported together rather than separately, showed an association with TB. This observation appears counter-intuitive. Further external validation of this algorithm, as we did for a TDA specifically developed for CLHIV20,34 may help refine the very final score, notably based on better detection of pericardial effusion, notably in the context of oedematous malnutrition.

Our study has limitations. First, as all paediatric tuberculosis diagnostic studies, our imperfect reference standard,23 which relied partly on clinical diagnosis, potentially led to biased assessments of identified predictors based on over or underdiagnosis of tuberculosis in the cohort. We used standardized ERC to validate all clinically diagnosed cases of tuberculosis; however, we cannot fully exclude heterogeneity in reclassification between countries. In addition, microbiological confirmation relied largely on Xpert Ultra trace results which further weakens our reference standard. Second, we assessed hospitalised children with SAM in tertiary care centres and the findings of the study might not be fully reproducible at secondary care levels where children with SAM are also admitted and where the diagnostic capacity and expertise might be lower than at tertiary care level. Third, the study was conducted in two high tuberculosis and HIV settings, and the findings may not be generalizable to settings with different tuberculosis and HIV epidemiological profiles. Fourth, we did not include urine tests detecting the mycobacterial antigen lipoarabinomannan in our study, as it was not recommended in children with SAM at the time. Lastly, the final diagnostic models were based on participants with complete data for the selected predictors and therefore may not be representative of the full cohort as more severely unwell children with adverse outcomes and missing data were excluded.

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale attempt at systematic tuberculosis screening in children hospitalised with SAM using Xpert Ultra. A further strength of the study was the uniform WHO case definitions for SAM, which minimized heterogeneity in the determination of nutritional status for children.5

The roadmap towards ending tuberculosis calls for comprehensive efforts to improve tuberculosis case finding to prevent tuberculosis deaths in children with malnutrition.6 Without a perfect childhood tuberculosis point-of-care test, screening and diagnosis will rely on approaches combining microbiological, clinical, radiological, and biomarkers such as lipoarabinomannan. Advances in the development of evidence-based scores have resulted in specific tuberculosis TDAs that could enable healthcare professionals make informed decisions by considering multiple variables, thereby promoting standardized approaches applicable to lower health facilities where diagnosis of tuberculosis in children is constrained.20,24,29 Also, new digital tools including artificial intelligence (AI) reading of CXR and availability of low-cost POCUS can facilitate the use of CXR and AUS in resource limited settings.

Our findings indicate that the burden of tuberculosis in hospitalised children with SAM is very high hence requiring systematic screening, and that the traditional clinical approach may not be sufficient. The acute pneumonia-like presentation of childhood tuberculosis in this group calls for a systematic screening of tuberculosis in children with combined SAM and acute pneumonia, taking into consideration health economics aspects and costs.14,31 WHO has recently suggested to incorporate tuberculosis TDAs into existing case detection strategies to facilitate the decentralization of clinical tools and enable easier identification of tuberculosis in children. Children with SAM are fast-tracked through the algorithm to reduce time to treatment decision but there was no formal evaluation of these TDAs in children with SAM. Another advantage of TDAs is that they can further evolve and improve by including new tests or biomarkers. The traditional approach to external validation of TDAs to determine their transportability may need to be adapted to the rapid cycle needed to constantly improve childhood tuberculosis diagnosis and provide access for children to the disease management they need. Their field feasibility, acceptability by healthcare workers, and eventually impact on case detection and reduction in mortality will also need further evaluation. External validation of the diagnostic models developed in this study is planned to evaluate their feasibility and effectiveness as part of a comprehensive TDA-based approach implemented at lower levels of care in high TB burden settings.35

Contributors

OM, MB and EW conceived and designed the TB-Speed study and led it at the international level. CC, OM, MB, and EW contributed to the development of this diagnostic study. CR coordinated study implementation at the international level while PS and GB coordinated study implementation in Zambia and Uganda respectively. SMG provided scientific guidance and expertise for the study, through the Scientific Advisory Board. CC, VM, BN, MI, KC, EB, PS, GB and EW implemented the study and enrolled participants. OM, MHN, CR and CC had access to and verified the underlying data. MHN performed the statistical analysis. CC, OM, CR, MHN, MB and EW contributed to the interpretation of the results. CC and CR wrote the first draft and all authors reviewed and approved the final version of the report and the manuscript. CC, OM, MB, EW were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Study data will not be publicly available. Data could be made available by the sponsor (Inserm) to interested researchers on request to the corresponding author under a data transfer agreement.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Unitaid (Grant number Grant number 2017-15-UBx-TB-SPEED) and sponsored by Inserm (Pôle de Recherche Clinique), Paris, France. We thank the Ministries of Health and National Tuberculosis programs in Zambia and Uganda for their support. We thank the members of the independent data monitoring committee, Muriel Rabilloud (chair, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, France): Mohammod Jobayer Chisti (Dhaka Hospital, Dhaka, Bengladesh), and Helena Rabbie (Tygerberg Hospital, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa), and the members of the TB-Speed Scientific Advisory Board who gave technical advice on the design of the study and approved the protocol: Steve Graham (chair, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia), Anneke Hesseling (Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa), Luis Cuevas (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK), Christophe Delacourt (Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades, France), Sabine Verkuijl (WHO, Switzerland), Philippa Musoke (Makerere University, Uganda), Mark Nicol (University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia), Elizabeth Maleche-Obimbo (University of Nairobi, Kenya), and Chishala Chabala (University of Zambia) who represented other TB-Speed investigators at Scientific Advisory Board meetings. We thank all the children and their families who participated in the trial, and the healthcare workers of the participating hospitals and laboratories. Preliminary findings from this study were presented at the Union Conference 2022, as abstract AS-UnionConf-2022-0103.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102688.

Contributor Information

Chishala Chabala, Email: chishala.chabala@unza.zm.

TB-Speed SAM study group:

Olivier Marcy, Angeline Serre, Anne Badrichani, Manoa Razafimanantsoa, Julien Poublan, Aurélia Vessière, Clémentine Roucher, Estelle Occelli, Aurélie Beuscart, Aurélie Charpin, Gemma Habiyambere, Salomé Mesnier, Eric Balestre, Nicolas Koskas, Marc D'Elbée, Hélène Font, Minh Huyen Ton Nu Nguyet, Maryline Bonnet, Manon Lounnas, Hélène Espérou, Sandrine Couffin-Cadiergues, Alexis Kuppers, Benjamin Hamze, Eric Wobudeya, Gerald Bright Businge, Faith Namulinda, Robert Sserunjogi, Rashidah Nassozi, Charlotte Barungi, Aanyu Hellen, Muwonge Doreen, Eva Kagoya, Serene Aciparu, Chemutai Sophia, Samuel Ntambi, Amir Wasswa, Juliet Nangozi, Chishala Chabala, Veronica Mulenga, Perfect Shankalala, Chimuka Hambulo, Vincent Kapotwe, Marjory Ngambi, Kunda Kasakwa, Mirriam Kanyama, Uzima Chirwa, Kapula Chifunda, Gae Mundundu, Susan Zulu, Grace Nawakwi, Teddy Siasulingana, Diana Attan Himwaze, Jessy Chilonga, Maria Chimbini, Mutinta Chilanga, Daniel Chola, Eustace Mwango, Bwendo Nduna, Muleya Inambao, Mwamba Pumbwe, Mwate Mwambazi, Barbara Halende, Wyclef Mumba, Endreen Mankunshe, Maureen Silavwe, Moses Chakopo, Roy Moono, Chalilwe Chungu, Kevin Zimba, Monica Kapasa, and Khozya Zyambo

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.World-Health-Organisation . World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2023. Global tuberculosis report 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dodd P.J., Yuen C.M., Sismanidis C., Seddon J.A., Jenkins H.E. The global burden of tuberculosis mortality in children: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):e898–e906. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30289-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unicef-WHO-World-Bank-Group . World Health Organisation and World Bank Group; 2023. Levels and trends in child malnutrition-Unicef/WHO/World bank joint child malnutrition estimates New York UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Black R.E., Victora C.G., Walker S.P., et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382(9890):427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World-Health-Organisation. Guideline . World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2013. Updates on the management of acute severe malnutrition in infants and children. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World-Health-Organisation . Geneva World Health Organisation; 2023. Roadmap towards ending TB in children and adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel L.N., Detjen A.K. Integration of childhood TB into guidelines for the management of acute malnutrition in high burden countries. Public Health Action. 2017;7(2):110–115. doi: 10.5588/pha.17.0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vonasek B.J., Radtke K.K., Vaz P., et al. Tuberculosis in children with severe acute malnutrition. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022;16(3):273–284. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2022.2043747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lonnroth K., Castro K.G., Chakaya J.M., et al. Tuberculosis control and elimination 2010-50: cure, care, and social development. Lancet. 2010;375(9728):1814–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60483-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra R.K. Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):460S–463S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.2.460S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha P., Davis J., Saag L., et al. Undernutrition and tuberculosis: public health implications. J Infect Dis. 2019;219(9):1356–1363. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhargava A. Undernutrition, nutritionally acquired immunodeficiency, and tuberculosis control. BMJ. 2016;355 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaganath D., Mupere E. Childhood tuberculosis and malnutrition. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(12):1809–1815. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chisti M.J., Graham S.M., Duke T., et al. A prospective study of the prevalence of tuberculosis and bacteraemia in Bangladeshi children with severe malnutrition and pneumonia including an evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF assay. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaCourse S.M., Chester F.M., Preidis G., et al. Use of Xpert for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in severely malnourished hospitalized Malawian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(11):1200–1202. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munthali T., Chabala C., Chama E., et al. Tuberculosis caseload in children with severe acute malnutrition related with high hospital based mortality in Lusaka, Zambia. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2529-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonnet M., Nansumba M., Bastard M., et al. Outcome of children with presumptive tuberculosis in mbarara, rural Uganda. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(2):147–152. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunasekera K.S., Vonasek B., Oliwa J., et al. Diagnostic challenges in childhood pulmonary tuberculosis—optimizing the clinical approach. Pathogens. 2022;11(4):382. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11040382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World-Health-Organisation . 2022. WHO Operational handbook on tuberculosis, Module 5; Management of tuberculosis and children and adolescents. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcy O., Borand L., Ung V., et al. A treatment-decision score for HIV-infected children with suspected tuberculosis. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lounnas M., Diack A., Nicol M.P., et al. Laboratory development of a simple stool sample processing method diagnosis of pediatric tuberculosis using Xpert Ultra. Tuberculosis. 2020;125 doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2020.102002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham S.M., Ahmed T., Amanullah F., et al. Evaluation of tuberculosis diagnostics in children: 1. Proposed clinical case definitions for classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis disease. Consensus from an expert panel. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(suppl 2):S199–S208. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham S.M., Cuevas L.E., Jean-Philippe P., et al. Clinical case definitions for classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis in children: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S179–S187. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunasekera K.S., Walters E., van der Zalm M.M., et al. Development of a treatment-decision algorithm for human immunodeficiency virus-uninfected children evaluated for pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(4):e904–e912. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venables W.N., Ripley B.D. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. Modern applied statistics with S-PLUS. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steyerberg E.W. Springer International Publishing; 2019. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Firth D. Bias reduction of maximum likelihood estimates. Biometrika. 1993;80(1):27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. Meeting Report: high-priority target product profiles for new tuberculosis diagnostics: report of a consensus meeting; p. 98. [Member, Expert Committee] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunasekera K.S., Marcy O., Munoz J., et al. Development of treatment-decision algorithms for children evaluated for pulmonary tuberculosis: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7(5):336–346. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(23)00004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osorio D.V., Munyangaju I., Muhiwa A., Nacarapa E., Nhangave A.V., Ramos J.M. Lipoarabinomannan antigen assay (TB-LAM) for diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis in children with severe acute malnutrition in Mozambique. J Trop Pediatr. 2021;67(3) doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcy O., Wobudeya E., Font H., et al. Effect of systematic tuberculosis detection on mortality in young children with severe pneumonia in countries with high incidence of tuberculosis: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(3):341–351. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belard S., Heller T., Orie V., et al. Sonographic findings of abdominal tuberculosis in children with pulmonary tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(12):1224–1226. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vonasek B.J., Kumwenda T., Gumulira J., et al. Point-of-Care ultrasound for tuberculosis in young children with severe acute malnutrition. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2023;43(2):e65–e67. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000004158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roucher C., Huyen Ton Nu Nguyet M., Chabala C., et al. 53rd union World conference on lung health. Virtual conference the international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease (IJTLD) 2022. Feasibility and performance of the PAANTHER treatment decision algorithm in HIV-infected children with presumptive tuberculosis: the prospective multicentre TB-speed HIV study; p. S253. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decide-TB-Project . 2024. Improving the diagnosis of tuberculosis in children.https://decide-tb.com/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.