Abstract

Inulin-type fructan (ITF) defined as a polydisperse carbohydrate consisting mainly of β-(2–1) fructosyl-fructose links exerts potential prebiotics properties by selectively stimulating the growth of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. This study reported the modulation of human gut microbiota in vitro by ITF from Codonopsis pilosula roots using 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. The microbiota community structure analysis at genus levels showed that 50 mg/mL ITF significantly stimulated the growth of Prevotella and Faecalibacterium. LEfSe analysis showed that ITF at 25 and 50 mg/mL primarily increased the relative abundance of genera Parabacteroides and Alistipes (LDA Score > 4), and genera Prevotella and Faecalibacterium (LDA Score > 4) as well as Acidaminococcus, Megasphaera, Bifidobacterium and Megamonas (LDA Score > 3.5), respectively. Meanwhile, ITF at 25 and 50 mg/mL exhibited the effects of lowering pH values of samples after 24 h fermentation (p < 0.05). The results indicated that ITF likely has potential in stimulating the growth of Prevotella and Faecalibacterium as well as Bifidobacterium of human gut microbiota.

Keywords: Codonopsis pilosula, Fructan, Prebiotics, Human gut bacteria

Introduction

Inulin-type fructan (ITF), a kind of indigestible carbohydrate, exhibits a linear structure comprised of β-D-fructose via β-(1 → 2)-fructosyl glycosidic bonds and terminated with an α-D-glucose. Increasing evidence showed that ITF exhibited multiple bioactivities such as neuroprotection, immunoregulation, gut microbiota regulation, prebiotic activity, and some potential pharmaceutical functions including stabilization of proteins and modified drug delivery [1–5]. In particular, the prebiotic activity of ITF especially stimulating Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus bacteria, is frequently highlighted [6–8].

Degrees of polymerization (DP) are commonly used to represent the number of fructose units in ITF. Different ITFs from different plant sources exhibit different DP. Generally, the short-chain ITF exhibits a DP of 2–10 and the long chain ITF refers to those with a DP of 10–60 [8]. The modulatory effect of ITF on gut microbiota is affected by both the DP of ITF and the host gut bacteria ecology.

Radix Codonopsis, derived from the roots of C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf., C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. Var. modesta (Nannf.) L.T. Shen and C tangshen Oliv, has been used as traditional Chinese medicine beneficial for spleen and lung in China [9]. In recent years, C. pilosula polysaccharides have attracted more and more attention of researchers and have been reported to show various functions. Gong et al. found that C. pilosula polysaccharides had a protective effect on the lungs in LPS- and Escherichia coli-induced acute lung injury mouse models by attenuating the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) induced by LPS and E. coli [10]. Wang and his colleagues reported that C. pilosula polysaccharides exhibited neuroprotective effects by attenuating Tau hyperphosphorylation and cognitive impairment in hTau infected mice and inhibiting Aβ toxicity and cognitive defects in APP/PS1 mice [11, 12]. A polysaccharide isolated from C. pilosula roots attenuated carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis by modulating TLR4/NF-κ and TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway [13]. Xie et al. showed that oligosaccharides and polysaccharides from C. pilosula exhibited antifatigue and antihypoxia activities in mice basing on the weight-loaded swimming test and the normobarie hypoxia test, respectively [14].

ITF is one of polysaccharides in C. pilosula roots and frequently isolated by many researchers. As early as 2005, Ye et al. reported the isolation of an ITF from C. pilosula and its antitumor activity in vitro [15]. Recently, increasing researches regarding ITF from C. pilosula and its bioactivities such as anti-inflammatory and prebiotic activities are arising [16, 17]. Previously, we obtained an ITF with an estimated DP of 31 from C. pilosula roots, and it exhibited obvious anti-gastric ulcer effects [18]. In this study, we reported the isolation and human gut bacteria modulation in vitro of an ITF with an estimated DP of 13 from C. pilosula roots. The results demonstrated that the ITF exhibited significant growth stimulation on genera Prevotella and Faecalibacterium, as well as Bifidobacterium at a higher fermented concentration in in vitro fecal fermentation.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Chemicals

The roots of C. pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. were collected from Pingshun county in Shanxi province, China, and identified by Professor Jianping Gao. The specimen (2020–10-MCM01) was kept at the School of Pharmaceutical Science, Shanxi Medical University. D101 macroporous resin (AR) was purchased from KeLong Chemical Reagent Factory (Chengdu, China) and 95% ethanol was purchased from Hebei RuiKang Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Hengshui,China).

Extraction and Isolation of ITF from C. pilosula Roots

The dried roots of C. pilosula (5 kg) were crushed and extracted two times with methanol (10:1, v/w) by reflux at 60 °C for 1 h. The residue after filtration with gauze was extracted two times with distilled water (10:1, v/w) by reflux at 100 °C for 2 h. The water extract was subjected to D101 macroporous resin column chromatography eluted with distilled water. The water elution was precipitated with 80% ethanol to obtain the precipitate (270 g). The precipitate was dissolved in distilled water and subjected to a 5,000 ultrafiltration membrane (Millipore Corporation, US) to obtain ITF (180 g) after freeze-dried.

Homogeneity and NMR Analysis of ITF

The homogeneity of ITF was determined by high-performance gel permeation chromatography (HPGPC) performed with a LC-10AT HPLC system (SHIMADZU, Kytot, Japan) fitted with a Tskgel G4000 PWXL column (300 mm × 8 mm) and a Shodex RI-20H refractive index detector. The mobile phase was ultrapure water and the flow rate was 0.3 mL/min at 35 °C. ITF (30 mg) was dissolved in D2O in a 5-mm NMR tube and measured for 1H- and 13C-NMR on an AVANCE III 400 MHz spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany).

Fecal Fermentation In Vitro

The fresh feces samples were collected from three healthy donors (Chinese, 1 Male and 2 Female, aged 23–28) who had not taken any antibiotics for at least six months, which was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shanxi Medical University (2022SJL25). Then the fecal samples were mixed with an equal amount of feces (67 g) from each donor, and diluted with 1000 mL PBS (pH 7.0) to obtain a 20% (w/w) solution, and subsequently mixed well using a vortex mixer. Then the feces samples were filtered through three layers of soup bags to remove food-derived debris and immediately transferred into an anaerobic workstation (A55, Don Whitley Scientific, UK). The atmosphere composition in the anaerobic workstation was 85% N2, 5% CO2, and 10% H2.

The basal medium was prepared according to the previous method [19] with minor modifications. Generally, 0.5 g peptone, 1.0 g yeast extract, 25.0 mg NaCl, 10.0 mg K2HPO4, 10.0 mg KH2PO4, 2.5 mg MgSO4, 2.5 mg CaCl2, 0.5 g NaHCO3, 5.0 mg hemin, 115.0 mg cysteine-HCl, 125.0 mg bile salt, 0.25 g resazurin, 0.5 mL Tween 80 and 2.5 µL vitamin K1 were dissolved in 250 mL distilled and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 0.1 mol/L HCl solution. The basal medium was sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min before use.

A volume of 5 mL of sterilized ITF solution at a designed concentration (25 mg/ml and 50 mg/ml), ultrapure water (CK group) was thoroughly mixed with 22.5 mL of fecal inoculum and 22.5 mL of basal medium using a vortex mixer. The experimental samples were transferred into different anaerobic sealed tubes, which were subsequently incubated at 37 °C and cultured for 24 h. Five replicate experiments were performed under the same conditions.

Analysis of Gut Microbiota

After fermentation for 24 h, PureLink™ Microbiome DNA purification kit (Invitrogen, USA) was used for extracting DNA from stool samples according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR amplification of the V3-V4 hyper variable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA was done with universal primers: 338 F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGG CAGCAG-3′), and 806R (5′- GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Next-generation sequencing of the V3–4 region of the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene was performed on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, Novogene). Sequenced DNA was analyzed using QIIME2 (version 2019.7), and alpha-rarefaction curves were achieved. Taxonomy was determined using the Greengenes classifier. A phylogenetic tree was generated and Beta diversity was calculated using Unweighted UniFrac distance matrices. Alpha diversity was calculated using Faith’s Phylogenetic Diversity test. An unweighted UniFrac distances dot-plot was created using Prism (GraphPad, USA), version 8.2.1.

Determination of pH Value

The fecal slurries supplemented with ITF or water were sampled after 24 h and plunged into ice water for 5 min. These fecal slurries were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min to separate the supernatants (fermentation medium), and then the pH value of each supernatant was measured.

Statistical Analysis

The normalized taxonomic profile and Alpha, and Beta diversity indices were used for statistical tests by using the R software (http://www.r-project.org/). Differences between any of the two groups were analyzed using Wilcoxon's test. To ascertain whether the visually observed differences in microbiota community among groups were statistically significant, adonis analyses were performed. A p value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

Homogeneity and NMR Analysis of ITF

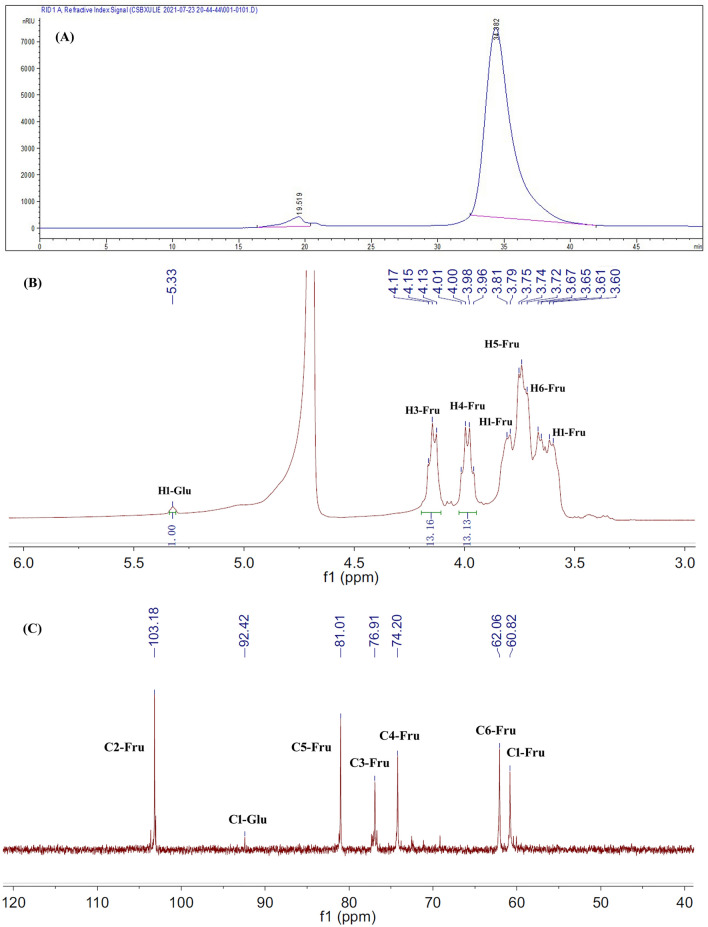

HPGPC was a method widely used for detecting the homogeneity of a polysaccharide. As shown in Fig. 1A, ITF exhibited a single and symmetrical sharp peak at 34.382 min on the HPGPC chromatogram, indicating that ITF was a homogeneous polysaccharide.

Fig. 1.

HPGPC (A), 1H- (B) and 13C-NMR (C) spectra of ITF

1H-NMR (Fig. 1B) and 13C-NMR (Fig. 1C) of ITF were completely consistent with the published data for ITF [7, 17, 20]. Briefly, in the 1H-NMR spectrum of ITF, several signals from 3.50 to 5.50 ppm occurred. The signal at 5.33 ppm was assigned to H-1 of terminal glucose residues in ITF and the signals at 4.15 and 4.00 ppm were assigned to H-3 and H-4 of fructose residues, respectively. The integration ratio of H3-Fru to H1-Glu was frequently used to estimate the DP value of ITF [7]. So, the DP of ITF was estimated to be 13 in this study as shown in Fig. 1B. In the 13C-NMR, six obvious carbon signals for fructose residues in ITF occurred at 103.18 ppm (C-2), 81.01 ppm (C-5), 76.91 ppm (C-3), 74.20 ppm (C-4), 62.06 ppm (C-6) and 60.82 ppm (C-1). Also, the signal at 92.42 ppm was assigned to C-1 of terminal glucose residues in ITF [7, 17, 20].

α-Diversity and β-Diversity of Human Gut Microbiota

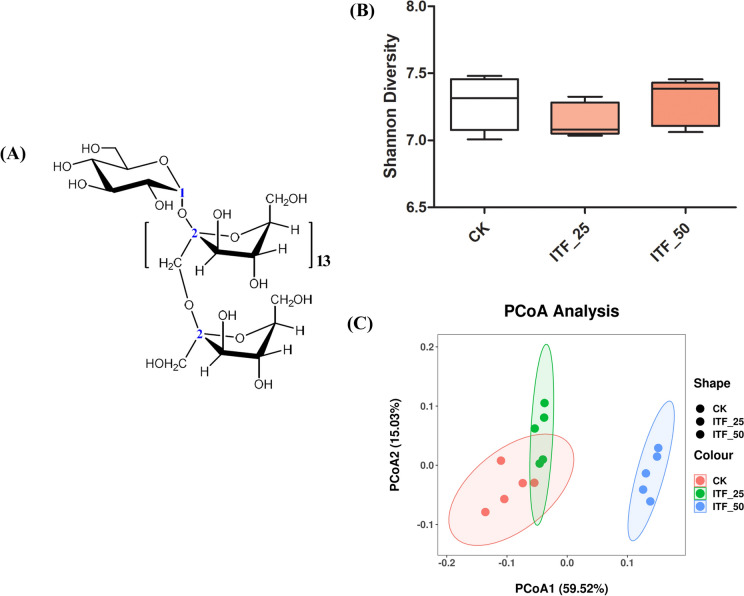

The α-diversity index Shannon diversity (Fig. 2B) indicated that there were no significant differences between the CK group and ITF groups. Principle co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) is one of the important analytical methods for β-diversity. As shown in Fig. 2C, PCoA1 and PCoA2 contributed 59.52% and 15.03% of the variation, respectively. These results demonstrated that the gut microbiota in the ITF groups were significantly different from that in the CK group.

Fig. 2.

Structure of ITF (A), Shannon Diversity (B) and PCoA (C) of gut microbiota of different group fecal samples

Composition of Human Gut Microbiota

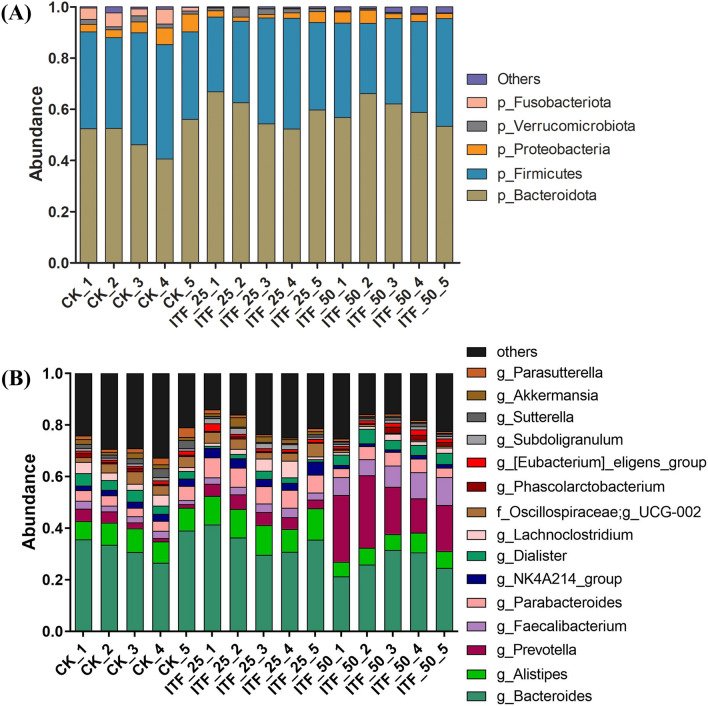

The microbiota community structure of fecal samples was examined at the phylum and genus levels. As shown in Fig. 3A, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobiota, and Fusobacteriota were the dominant bacteria in all fecal samples at the phylum level, and the dominant bacteria Bacteroidota and Firmicutes accounted for 88.8% and above 94% of total bacteria in CK group and in ITF groups, respectively. The ratio of Bacteroidota to Firmicutes between groups exhibited no significant differences. It was interesting that the relative abundance of Fusobacteriota was significantly lowered in ITF groups compared to the CK group, which was consistent with the previous study showing that polysaccharides from loquat leaves and fructooligosaccharide (FOS) decreased significantly the relative abundance of Fusobacteria at the phylum level in an in vitro fecal fermentation [21]. The phylum Fusobacteriota occasionally exhibited potential pathogenicity. Qi et al. reported that the relative abundance of Fusobacteriota at the phylum level was much higher in Tibetan piglets with yellow dysentery than that in Tibetan piglets with white dysentery and healthy Tibetan piglets [22]. In cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed rats, it was found that the bacterial in rat feces were enriched in Proteobacteria, Fusobacteriota and Actinobacteriota at the phylum level, which was then eliminated by the treatment of a combination of live Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Bacillus [23].

Fig. 3.

The microbiota community structure at the phylum level (A) and the genus level (B) of the different group fecal samples

At the genus level (Fig. 3B), it was shown that the dominant bacterium was Bacteroides (Bacteroidetes), Alistipes (Bacteroidetes), Prevotella (Bacteroidetes), Faecalibacterium (Firmicutes) and Parabacterium (Bacteroidetes) in all fecal samples, and Bacteroides was the most dominant genus, which was consistent with the report that the bacterial phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were dominated in gut of most healthy adults, and the genus Bacteroides was one of the most dominant genera in Bacteroides phylum [24]. The relative abundances of Prevotella and Faecalibacterium were significantly increased in the ITF (50 mg/mL) group compared to the CK group. The genus Prevotella was found to exhibit the capacity to break down a wide-range of plant-derived polysaccharides and was associated positively with high levels of carbohydrate, fruit and vegetable intake [25]. Prevotella histicola, an emerging probiotic, significantly alleviated depression in ovariectomized mice by improving the intestinal microbiota to inhibit central inflammation and may be therapeutically beneficial for postmenopausal depression [26]. The study by Kovatcheva-Datchary indicated that dietary fiber consumption increased the abundance of Prevotella in gut microbiota and improved glucose metabolism potentially by increasing glycogen storage [27]. So, ITF of this study was a potential prebiotic by stimulating Prevotella.

The genus Faecalibacterium is prevalent in the human gut and is one of the most promising microbes for the development of probiotics and biotherapeutics, and F. Prausnitzii, the species of the genus Faecalibacterium, is functionally considered a significant biomarker of gut health [28, 29]. The critical role of F. Prausnitzii in human health was reviewed in detail, which presented that the decrease of abundance in F. Prausnitzii was associated with gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer, and with metabolic syndromes such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and other diseases [30]. These data demonstrated that ITF could exhibit health benefits by increasing the relative abundances of Prevotella and Faecalibacterium in gut microbiota.

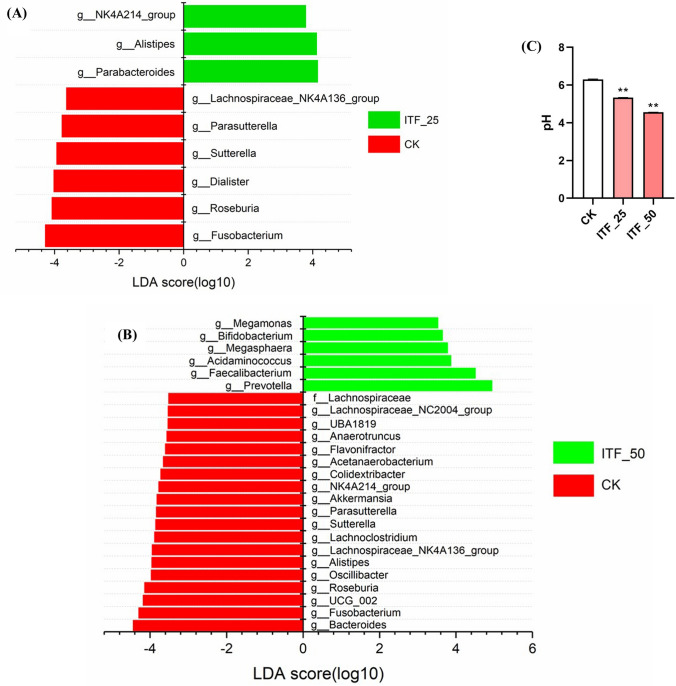

LEfSe Analysis

LEfSe (LDA Effect Size) is a useful analytical tool to find biomarkers with statistical differences among groups. As shown in Fig. 4, ITF at 25 mg/mL primarily increased the relative abundance of genera including Parabacteroides and Alistipes (LDA Score > 4) (Fig. 4A), and ITF at 50 mg/mL significantly increased the relative abundance of genera Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, (LDA Score > 4) as well as Acidaminococcus, Megasphaera, Bifidobacterium and Megamonas (LDA Score > 3.5) (Fig. 4B). The genus Alistipes consists of thirteen species, among of which some species exhibit helpful effects on human health, such as protecting against liver fibrosis and colitis, and some species are pathogenic in colorectal cancer [31]. The genus Parabacteroides also exhibits both beneficial and pathogenic effects on human health, such as protecting against colorectal cancer and obesity on the one hand and promoting inflammatory bowel disease on the other hand [32]. Meanwhile, ITF at both 25 mg/mL and 50 mg/mL significantly decreased the abundance of Fusobacterium compared to the CK (LDA Score > 4), which was consistent with the report by Yu et al. that inulin exhibited significant inhibition on pathogenic bacteria Fusobacterium [33].

Fig. 4.

LEfSE results among different groups (A and B) and the effect of ITF on pH values (C). ** p < 0.05 compared to CK

These data indicated that ITF exhibited different impacts on human gut microbiota at different concentrations, which reminded us that the dose was an important factor to be considered in evaluating the effect of some substances on the composition of gut microbiota.

Effects of ITF on pH Value

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) mainly including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are the main products from the fermentation of dietary fiber in the colon, and are responsible for the drop in pH in fermentation progress [34, 35]. The genus Prevotella was well known to produce succinate as a major product of fermentation in utilizing polysaccharides, which was rapidly decarboxylated to produce propionate playing a key role in gut protection [36]. The genus Faecalibacterium was also well-known butyrate-producing probiotics [37, 38]. As shown in Fig. 4C, the values of pH were significantly decreased after fermentation by ITF compared to the CK group (p < 0.05). The reason for lowering pH of ITF is not clear, and whether it is associated with production of SCFAs or not need to be revealed in subsequent experiments.

In conclusion, ITF is usually convinced to be prebiotic stimulating the growth of Bifidobacterium or Lactobacillus. However, ITF in this study exhibit the function of promoting the growth of Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, as well as Bifidobacterium and others and inhibiting the growth of Fusobacterium and others in human fecal fermentation in vitro.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U22A20375).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zhang S, Zhang Q, An L, Zhang J, Li Z, Zhang J, Li Y, Tuerhong M, Ohizumi Y, Jin J, Xu J, Guo YQ. A fructan from Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge showing neuroprotective and immunoregulatory effects. Carbohyd Polym. 2020;229:115477. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandeputte D, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Sailer M, Theis S. Prebiotic inulin-type fructans induce specific changes in the human gut microbiota. Gut. 2017;66:1968–1974. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly G. Inulin-type prebiotics–A review part 2. Altern Med Rev. 2009;14:36–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apolinário AC, de Lima Damasceno BP, de Macêdo Beltrão NE, Pessoa A, Converti A, da Silva JA. Inulin-type fructans: a review on different aspects of biochemical and pharmaceutical technology. Carbohyd Polym. 2014;101:368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mensink MA, Frijlink HW, Maarschalk KV, Hinrichs WLJ. Inulin, a flexible oligosaccharide. II: review of its pharmaceutical applications. Carbohyd Polym. 2015;134:418–428. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zou YF, Zhang YY, Zhu ZK, Fu YP, Paulsen BS, Huang C, Feng B, Li LX, Chen XF, Jia RY, Song X, He CL, Yin LZ, Lv C, Yin ZQ. Characterization of inulin-type fructans from two species of Radix Codonopsis and their oxidative defense activation and prebiotic activities. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101:2491–2499. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu YP, Li LX, Zhang BZ, Paulsen BS, Yin ZQ, Huang C, Feng B, Chen XF, Jia RR, Song X, Ni XQ, Jing B, Wu FM, Zou YF. Characterization and prebiotic activity in vitro of inulin-type fructan from Codonopsis pilosula roots. Carbohyd Polym. 2018;193:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tawfick MM, Xie HL, Zhao C, Shao P, Farag MA. Inulin fructans in diet: role in gut homeostasis, immunity, health outcomes and potential therapeutics. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;208:948–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao SM, Liu JS, Wang M, Cao TT, Qi YD, Zheng BG, Sun XB, Liu HT, Xiao PG. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Codonopsis: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;219:50–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gong ZG, Zhang SY, Gu BC, Cao JS, Mao W, Yao Y, Zhao JM, Ren PP, Zhang K, Liu B. Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharides attenuate Escherichia coli-induced acute lung injury in mice. Food Funct. 2022;13:7999–8011. doi: 10.1039/D2FO01221A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q, Xia YY, Luo HB, Huang S, Wang YJ, Shentu YP, Razak Mahaman YA, Huang F, Ke D, Wang Q, Liu R, Wang JZ, Zhang B, Wang XC. Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide attenuates Tau hyperphosphorylation and cognitive impairments in hTau infected mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 2018;11:437. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wan L, Zhang B, Luo HB, Xu ZD, Huang S, Yang FM, Liu Y, Razak Mahaman YA, Ke D, Wang Q, Liu R, Wang JZ, Shu XJ, Wang XC. Codonopsis pilosula polysaccharide attenuates Aβ toxicity and cognitive defects in APP/PS1 mice. Aging. 2020;12:13422–13436. doi: 10.18632/aging.103445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meng XQ, Kuang HX, Wang QH, Zhang H, Wang D, Kang TG. A polysaccharide from Codonopsis pilosula roots attenuated carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis via modulation of TLR4/NF-κ and TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;119:110180. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie Q, Sun YT, Cao LL, Chen LN, Chen J, Cheng XM, Wang CH. Antifatigue and antihypoxia activities of oligosaccharides and polysaccharides from Codonopsis pilosula in mice. Food Funct. 2020;11:6352–6362. doi: 10.1039/D0FO00468E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye G, Li C, Huang CG, Li ZX, Wang XL, Chen YZ. Chemical Structure of fructosan from Codonopsis pilosula. China J Chin Materia Med. 2005;30:1338–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou YF, Li CY, Fu YP, Feng X, Peng X, Feng B, Li LX, Jia RY, Huang C, Song X, Lv C, Ye G, Zhao L, Li YP, Zhao XH, Yin LZ, Yin ZQ. Restorative effects of inulin from Codonopsis pilosula on intestinal mucosa immunity, anti-inflammatory activities and gut microbiota of immunosuppressed mice. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:786141. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.786141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng Y, Xu YJ, Chang C, Qiu ZP, Hu JJ, Wu Y, Zhang BH, Zheng GH. Extraction, characterization and anti-inflammatory activities of an inulin-type fructan from Codonopsis pilosula. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li JK, Wang T, Zhu ZC, Yang FR, Cao LY, Gao JP. Structure features and anti-gastric ulcer effects of inulin-type fructan ITF from the roots of Codonopsis pilosula (Franch) Nannf. Molecules. 2017;22:2258. doi: 10.3390/molecules22122258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou WT, Yan YM, Mi J, Zhang HC, Lu L, Luo Q, Li XY, Zeng XX, Cao YL. Stimulated digestion and fermentation in vitro by human gut microbiota of polysaccharides from Bee collected pollen of Chinese wolfberry. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(4):898–907. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French AD. Chemical and physical properties of fructans. J Plant Physiol. 1989;134:125–136. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(89)80044-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu DT, Fu Y, Guo H, Yuan Q, Nie XR, Wang SP, Gan RY. In vitro simulated digestion and fecal fermentation of polysaccharides from loquat leaves: dynamic changes in physicochemical properties and impacts on human gut microbiota. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;168:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qi M, Cao ZP, Shang P, Zhang H, Hussain R, Mehmood K, Chang ZY, Wu QX, Dong HL. Comparative analysis of fecal microbiota composition diversity in Tibetan piglets suffering from diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) Microb Pathog. 2021;158:105106. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lv LX, Mu DG, Du YL, Yan R, Jiang HY. Mechanism of the immunomodulatory effect of the combination of live Bifidobacterium, lactobacillus, enterococcus, and bacillus on immunocompromised rats. Front Immunol. 2021;12:694344. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.694344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wexler AG, Goodman AL. An insider’s perspective: Bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17026. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gálvez EJC, Iljazovic A, Amend L, Lesker TR, Renault T, Thiemann S, Hao LX, Roy U, Gronow A, Charpentier E, Strowig T. Distinct polysaccharide utilization determines interspecies competition between intestinal Prevotella spp. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang FR, Liu XJ, Xu S, Hu ST, Wang SS, Shi DB, Wang KC, Wang ZX, Liu QQ, Li S, Zhao SY, Jin KK, Wang C, Chen L, Wang FY. Prevotella histicola mitigated estrogen deficiency-induced depression via gut miacrobiota-dependent modulation of inflammation in ovariectomized mice. Front Nutrition. 2022;8:805465. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.805465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Nilsson A, Akrami R, Lee YS, De Vadder F, Arora T, Hallen A, Martens E, Björck I, Bäckhed F. Dietary-fiber-induced improvement in glucose metabolism is associated with increased abundance of Prevotella. Cell Metab. 2015;22:971–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filippis FD, Pasolli E, Ercolini D. Newly explored Faecalibacterium diversity is connected to age, lifestyle, geography, and disease. Curr Biol. 2020;30:4932–4943. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsae M, Sarafraz N, Moaddab SY, Leylabadlo HE. The important of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in human health and disease. New Microbes and New Infections. 2021;43:100928. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2021.100928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leylabadlo HE, Ghotaslou R, Feizabadi MM, Farajinia S, Moaddab SY, Ganbarov K, Khodadadi E, Tanomand A, Sheykhsaran E, Yousefi B, Kafil HS. The critical role of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in human health: an overview. Microb Pathog. 2020;149:104344. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker BJ, Wearsch PA, Veloo ACM, Rodriguez-Palacios A. The genus Alistipes: gut bacteria with emerging implications to inflammation, cancer, and mental health. Front Immunol. 2020;11:906. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezeji JC, Sarikonda DK, Hopperton A, Erkkila HL, Cohen DE, Cominelli MSP, F, Kuwahara T, Dichosa AEK, Good CE, Jacobs MR, Khoretonenko M, Veloo A, Rodriguez-Palacios A, Parabacteroides distasonis: intriguing aerotolerant gut anaerobe with emerging antimicrobial resistance and pathogenic and probiotic roles in human health. Gut Microbes. 2021;13:e1922241. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1922241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu CX, Ahmadi S, Shen SH, Wu DM, Xiao H, Ding T, Liu DH, Ye XQ, Chen SG. Structure and fermentation characteristics of five polysaccharides sequentially extracted from sugar beet pulp by different methods. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;126:107462. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, Verbeke K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:461–478. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratajczak W, Rył A, Mizerski A, Walczakiewicz K, Sipak O, Laszczyńska M. Immunomodulatory potential of gut microbiome-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) Acta Biochim Pol. 2019;66:1–12. doi: 10.18388/abp.2018_2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purushe J, Fouts DE, Morrison M, White BA, Mackie RI, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Nelson KE. Comparative genome analysis of Prevotella ruminicola and Prevotella bryantii: insights into their environmental niche. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:721–729. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9692-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:189–200. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louis P, Young P, Holtrop G, Flint HJ. Diversity of human colonic butyrate-producing bacteria revealed by analysis of the butyryl-CoA: acetate CoA-transferase gene. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:304–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]