Abstract

Prebiotics play a pivotal role in fostering probiotics, essential contributors to the creation and maintenance of a conducive environment for beneficial microbiota within the human gut. To qualify as a prebiotic, a substance must demonstrate resilience to stomach enzymes, acidic pH levels, and intestinal bacteria, remaining unabsorbed in the digestive system while remaining accessible to gut microflora. The integration of prebiotics and probiotics into our daily diet establishes a cornerstone for optimal health, a priority for health-conscious consumers emphasizing nutrition that supports a balanced gut flora. Prebiotics offer diverse biological functions in humans, exhibiting antiobesity, antimicrobial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, and cholesterol-lowering properties, along with preventing digestive disorders. Numerous dietary fibers possessing prebiotic attributes are inadvertently present in our diets, emphasizing the broader significance of prebiotics. It is crucial to recognize that, while all dietary fibers are prebiotics, not all prebiotics fall under the category of dietary fibers. The versatile applications of prebiotics extend across various industries, such as dairy, bakery, beverages, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and other food products. This comprehensive review provides insights into different prebiotics, encompassing their sources, chemical compositions, and applications within the food industry.

Keywords: Prebiotic, Dietary fiber, Probiotics, Heath effect, Oligosaccharide

Introduction

A balanced diet plays a critical, intricate, and significant role in preserving the diversity of gut flora. A nutrient-rich, balanced diet that positively influences gut flora is highly sought after by health-conscious consumers and serves as the foundational basis for overall health. The simplest strategy for nurturing a thriving population of healthy microbiota is to incorporate probiotics, prebiotics, and dietary fibers into the daily diet. Probiotics are live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer several health benefits on the host [1]. Prebiotics nourish existing probiotics in the gut, helping to sustain beneficial microbiota. As prebiotics are utilized by probiotics it helps to protect the natural habitat of the beneficial microbiota in the human gut. If prebiotics and probiotics are taken together, their beneficial effects can be increased and can prolong their advantages. According to the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), dietary prebiotics are “selectively fermented ingredient that results in specific changes in the composition and/or activity of the gastrointestinal microbiota, thus conferring benefit(s) upon host health”. To be classified as a prebiotic, any edible compound must satisfy certain predefined criteria like resistance to stomach pH and intestinal enzymes, should not be absorbed in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and stimulate the growth of the intestinal bacteria, which enhances host health [2]. In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the crucial role that gut health plays in maintaining overall well-being. Various food products have been fortified with different prebiotics like galacto-oligosachharides (GOS), fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) inulin, gluco-oligosaccharides (GluOS), xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS) etc. The polysaccharide or oligosaccharide content in the daily recommended food intake should be 10 g [3]. Several organizations like Codex Alimentarius, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Commission, the European Food Safety Authority, Health Canada, and Food Standards Australia New Zealand have provided prebiotic usage guidelines [4]. In India Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) has been at the forefront of ensuring that the Indian population has access to safe and beneficial food products. One such approved, attention-grabbing category is prebiotics. The FSSAI has permitted a total of 16 prebiotics to be used as ingredients namely polydextrose, soybean oligosaccharides, isomalto-oligosaccharides (IMO), FOS, GluOS, XOS, inulin, isomaltulose, gentio-ologsaccharides, lactulose, lactoferrin, sugar alcohols (lactitol, sorbitol, maltitol, etc.), GOS, partially hydrolyzed guar gum (guar gum derivative), pectin and resistant dextrin. In this review, an overview of the approved prebiotics, source, chemical composition, mechanism, and application in the food industry are presented.

Dietary Fibers

Dietary fibers are present in plants, cereals, legumes, fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds. They are complex carbohydrates and these long-chain polysaccharides resist digestion by small intestine enzymes and avoid absorption, instead undergoing fermentation in the large intestine. Typically, they have a degree of polymerization (DP) equal to or higher than 3. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has defined dietary fibres as carbohydrate polymers with ten or more monomeric units that are not digested by the endogenous enzymes present in the small intestine of humans [5]. However, FDA has defined the term dietary fiber to only those fibers that could have beneficial human physiological health effects. This definition includes plant-based naturally occurring fibers that are “intact and intrinsic” in plant (found in whole grains, vegetables, and fruits), and isolated from plant sources or synthetic non-digestible carbohydrates with beneficial health effects.

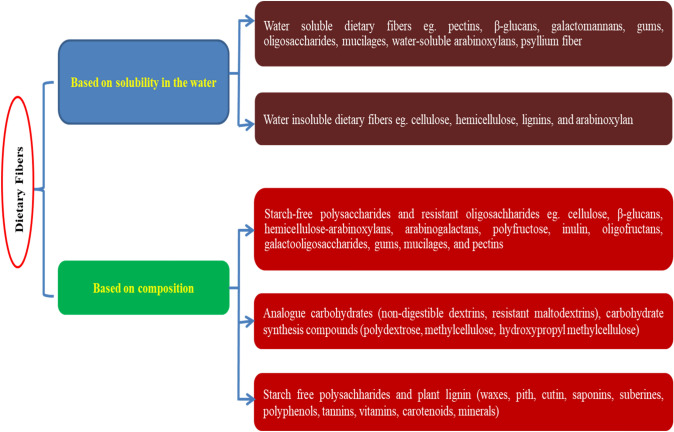

The enzymes present in the human intestine can only digest α (1 → 4) glycosidic bonds, however α (1 → 6) bonds are present in fibers that cannot be easily broken down, hence they reach the colon and get partially fermented by the micro-organisms [6]. Not all prebiotics are dietary fibres, but all dietary fibres are prebiotics. Undigested dietary fibers passing through the GI tract stimulate beneficial bacteria growth and/or activity in the large intestine to be classified as prebiotics. The FDA has included several non-digestible carbohydrates under the definition of dietary fibers like beta-glucan soluble fiber, psyllium husk, cellulose, guar gum, pectin, locust bean gum, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, mixed plant cell wall fibers, arabinoxylan, alginate, inulin and inulin-type fructans, high amylose starch (resistant starch 2), GOS, polydextrose, resistant maltodextrin/dextrin, cross linked phosphorylated RS4, glucomannan and acacia (gum arabic). Dietary fibers can be classified based on their composition or water solubility as depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Classification of dietary fibers

Classification of Prebiotics

According to the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP), prebiotics are broadly categorized based on their chemical nature into carbohydrates, phenolics, phytochemicals (like curcumin, naringenin, or hesperetin), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA, including linoleic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid). Carbohydrates encompass oligosaccharides (like inulin-type fructans—ITF, GOS, arabinoxylans—AX, XOS, and human milk oligosaccharides—HMOs) as well as polysaccharides (including glucans, isomaltodextrin, and resistant starch). The versatility of carbohydrates in promoting a conducive environment for beneficial gut bacteria underscores their significance in prebiotic designations.

Established prebiotics, include inulin, fructose oligosaccharide, galactose oligosaccharide, and lactulose. Additionally, potential prebiotics encompasses oligosaccharides like XOS, IMO, raffinose-family oligosaccharides, and isomaltose, polyols such as lactitol, xylitol, and mannitol, non-starch polysaccharides like pectin, β-glucan, and lignin, as well as starch polysaccharides such as resistant starch. In the realm of emerging prebiotics, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, PUFA, and vitamins add an exciting dimension to prebiotic research [7]. Though still being explored, these compounds show promise as potential contributors to a balanced, flourishing gut microbiome. This comprehensive classification highlights the diversity of prebiotics, including both established and potential candidates playing a pivotal role in fostering a healthy gut microbiome.

Polydextrose

Polydextrose (C12H22O11) is a soluble fiber with an average molecular weight of 2160 Daltons (D). It is a highly branched polysaccharide composed of random cross-linked glucose units with all possible combinations of α and β linkage i.e. 1 → 2, 1 → 3, 1 → 4 and 1 → 6, while both α and β 1 → 6 linkage dominates in the polymeric structure. Polydextrose also contains a minor amount of 1% citric acid and 10% sorbitol. The DPs of glucose oligomers in polydextrose vary ranging from 2 to 20, with an average DP of 12 [8, 9]. Due to its highly complex structure, polydextrose bypasses small intestine digestive enzymes, entering the colon intact for partial fermentation by inherent colonic microbes and about 60% is excreted with faeces. The intricate structure of polydextrose leads to incomplete and slow fermentation by a plethora of microbes. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and gases (CO2, H2, and methane) are produced as fermentation products [10].

Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides (OS) are low molecular weight carbohydrate-based polymers made of 3–10 sugar units. Many of these OS are not digested by human digestive enzymes and act as prebiotics that feed colon bacteria in the gut. OS include cyclodextrins, FOS, GOS, genti-oligosaccharides, glycosyl sucrose, IMO, isomaltulose, lactulose, lactosucrose, malto-oligosaccharides, and raffinose [11].

Soybean Oligosaccharides

Soybean oligosaccharide (SO) is a well-recognized prebiotic with Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) status. It is a mixture of soluble oligosaccharides obtained from soya seeds or soya whey. Soya seeds are a rich source of GOS mainly stachyose and raffinose, however SO extract containing sucrose, stachyose, raffinose and monosaccharides [including fructose (Fruc) and glucose (Glu)] about 50%, 25%, 10% and 15%, respectively was also reported. It tastes sweet like sugar with 70% more sweetness and no aftertaste. The raffinose and stachyose contain one or two galactose (Gal) connected with a glucose unit of sucrose. Thus, raffinose has the structure of Gal–Glu–Fruc, and stachyose has a Gal–Gal–Glu–Fruc structure [12] and is an important component of soya beans. Raffinose-series oligosaccharides (RSO) have an average concentration of 4.83 g per 100 g in soybean flour [13].

Isomalto-oligosaccharides

IMO are soluble dietary fibre approved by the FDA with GRAS status. They are short-chain carbohydrate blends obtained via starch enzymatic hydrolysis. Natural IMO sources are honey and fermented foods like soy sauce, sake and miso. The carbohydrate composition of IMO includes panose, isomaltose, isomaltotetraose, isomalto triose, isomalto pentaose and so on. It has a glucose unit attached at 40–95% with α-(1 → 6) glycosidic bond. The IMO has a DP value ranging from 2 to 8 and, it can be obtained from different carbohydrate sources such as starch, sucrose, dextran and maltose after serial reactions with alpha amylase, beta amylase and transglucosidase [11, 14].

Fructo-oligosaccharides

FOS are water-soluble dietary fibers with DP varying from 2 to 10 and are present in various vegetables and fruits like garlic, chicory, onion, asparagus, artichoke, and banana. The structure of FOS consists of a linear chain of fructose units having terminal glucose units bonded with β-(2 → 1) glycosidic bond (Glu–Fruc–Fruc–) which is not hydrolyzed by GI enzymes [15]. FOS can be obtained by the transfructosylation reaction of sucrose or by controlled hydrolysis of inulin. FOS is a inulin type fructan having DP < 10, low calorie and a common prebiotic in the food industry.

Galacto-oligosachharides

GOS is a short-chain carbohydrate, resulting in the extension of lactose (Glu–Gal–Gal–Gal–) molecules, these are the chain of 3 to 8 β-linked galactose units having glucose at the reducing end. It can be of two types (a) GOS with additional Gal units at C-3, C-4, or C-6 and (b) GOS obtained by enzyme-catalyzed trans glycosylation of lactose. It may also be produced by enzymatic conversion of bovine milk lactose, however, the effect of GOS depends on various factors such as enzyme source, enzyme dose, the origin of lactose, its concentration and, the process involved. Generally, GOS is a colourless water-soluble ingredient and is not hydrolyzed by digestive enzymes but fermented by colonic microbes into SCFA, H2 and CO2. It stimulates the metabolism and growth of healthy intestinal bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and inhibits the survival of E. coli, Salmonella, and Clostridia. The GOS was found to improve defecation, relieve constipation, have anti-cancerous properties, stimulate bone mineralization, and decrease the activity of harmful enzymes. GOS inhibits the growth of pathogens by producing anti-microbial components, which have a favourable impact on the immune system [16]. It is naturally present in breast milk and helps to stimulate the growth of intestinal lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. Since its positive effect, it is fortified to several dairy products like infant milk formulae, yoghurts etc. to enhance its functionality.

Gluco-oligosaccharides

GluOSs are made up of α (1–6) and α (1–2) β-d glucose subunits (Glu–Glu–). They are effective prebiotics because the α (1–2) bonds are indigestible to human gastric enzymes. GluOS are synthesized by using dextran sucrase enzyme on sucrose in the presence of maltose. It can also be produced by Leuconostoc fermentation, the resultant GluOS varies in amount and distribution of dominating α (1–6) linkages and less predominant α (1–2), α (1–3) and α (1–4) linkages [17].

Xylo-oligosaccharides

XOSs are polymers of xylose (Xyl) linked together by β-(1–4) bond with a DP value of 2–7 and are known as xylobiose, xylotriose and xylotetrose (Xyl–Xyl–). Rich sources of XOS are the plentiful and renewable agricultural crop waste. These can withstand high temperatures and are soluble in water [18]. Because XOS has β-(1–4) linkage, it is difficult to hydrolyze at low pH and is not broken down by digestive enzymes. Instead, it enters the colon and forms SCFAs [19].

Gentio-oligosaccharides

Gentio-oligosaccharides are oligosaccharides that contain glucose units linked with β (1–6) glycosidic linkage (Glu–Glu–Glu–) which is resistant to digestion by intestinal enzymes, making it a potential prebiotic [20]. It acts as a flavour enhancer due to its distinct stimulating bitter taste like coffee, cocoa, and chocolate. These are tolerant to heat and pH and are less viscous with good water absorption capacity.

Inulin

Inulin is a water-soluble dietary fiber and it is a heterogeneous mixture of fructose polymers linked through β(2–1) linkages (Glu–Fru–Fru–) [21]. Inulin is commonly found in plants and one of the richest sources is chicory roots. The energy value of inulin is low i.e. 1.5 kcal/g due to its indigestible nature. It has a DP between 3 and 60. A linear chain of β-2,1-linked d-fructofuranose molecules makes up inulin, and at the reducing end, a glucose residue forms a sucrose-type connection. The human small intestine finds it difficult to absorb and digest inulin due to the existence of β-(2–1)-d-frutosyl fructose bonds between the fructose unit and the isomeric carbon. Rather, it moves to the large intestine, where it might be broken down by lactobacilli and other gut microbes that can digest inulin by inulinase activity [22]. Inulin enhances the growth of bifidobacteria and hinders the growth of pathogenic bacteria like E. coli, Listeria and Salmonella. It has been reported that inulin can also increase calcium absorption (~ 20%) [23].

Isomaltulose

Isomaltulose is an isomer of sucrose, containing disaccharides glucose and fructose linked via α (1–6) linkage (Glu–Fru). However, sucrose is made up of glucose and fructose units linked via α (1–2) linkage. It has similar organoleptic properties to sucrose but has 50% more sweetness than sucrose [24]. It has several properties like slow hydrolysis, low glycemic index and is non-cariogenic. Since it carries prebiotic potential, it is generally used in food industries as a sucrose alternative. It stimulates the growth of probiotic strains like Lactobacilli, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus etc. [25].

Lactulose

Lactulose an isomer of lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and fructose sugars linked via β (1–4) glycosidic linkages (Gal–Fru), which could not be hydrolyzed by the digestive enzymes. It is soluble in water and has a sweetness that is 0.48–0.62 times more than sucrose, making it sweeter than lactose [26, 27]. It is non-cariogenic and oral microbes are not able to metabolize it. Lactulose is known for its bifidus factor, enhancing Bifidobacterium growth, and conferring various health benefits at low, medium, and high doses. It can be produced by heating milk to sterilization temperature, and can also act as an indicator for severely heated milk.

Lactoferrin

An iron-binding glycoprotein, lactoferrin (LF) is a single-chain protein consisting of 703 amino acids, folded in two lobes [28]. Its concentration is high in colostrum milk. It has a direct antimicrobial activity due to its unique structure, limits the adhesion and proliferation of microorganisms (viruses, bacteria and parasites) and even kills them. The antimicrobial effect of LF is mainly due to three mechanisms (a) it binds with iron with greater affinity and limits the iron requirement essential for microbial growth (b) it directly binds to the lipopolysaccharide of the microbial membrane, especially of Gram-negative bacteria and damages the structure and inhibits virus replication and (c) inhibits the binding and adhesion of pathogens to the host cells. Thus LF is known for its antimicrobial effects, but in strongly acidic conditions at pH < 3.5 such as during inflammation and infection, it releases the bonded iron which further catalyzes the formation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in pathogens' death [29]. The LF also has antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus, human hepatitis B and C, and HIV. LF protects neonates from some GI infections. Thus, the LF inhibits bacterial, viral, parasitic and fungal infections. LF promotes the growth of some probiotic microbes with low iron requirements such as bifidobacterial and lactobacilli. It also inhibits the growth of pathogenic bacteria, as it prevents the pathogen from binding to the host by binding to the lipopolysaccharide of the microbial membrane, eventually causing lysis of the pathogen [30]. It possesses several other bioactivities like antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anticancer properties.

Sugar alcohols

Sugar alcohols are low-digestible carbohydrates containing alcoholic groups, examples are lactitol, sorbitol, maltitol, xylitol etc. They are typically employed as a low-calorie bulk sweetener because they have roughly half the calories of sugar. Xylitol, sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, and lactitol act as a non-cariogenic agent as these are not fermented by the mouth bacteria. Some of the polyols like lactitol and maltitol can enhance mineral bioavailability. Moreover, xylitol promotes the remineralization of dental enamel [31]. Lactitol increases the growth of probiotic microbes and decreases the population of putrefactive microbes. However, the excessive consumption of polyols may produce laxative effects depending on the type, amount, consumption frequency and age of the consumer. The addition of more than 10% concentration of polyols in any food product needs an advisory statement on the label “Excessive consumption may produce laxative effects” [32]. Polyols are incompletely or slowly absorbed in the small intestine and then move to the large intestine where they are hydrolyzed into SCFA and gases. These are poorly absorbed in the blood and can cause minimal changes in blood sugar. Due to their slow hydrolysis during digestion, polyols do not increase the blood glucose level, so are preferably recommended to diabetic patients [31].

Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum (Guar Gum Derivative)

The guar plant is generally grown in India and Pakistan, and the guar seeds are processed into guar gum. Guar gum is a water-soluble polysaccharide commonly used as a stabilizer and thickener. Chemically it is galactomannan consisting of a mannose (Man) chain branched with galactose units (Man–Gal–). Due to its viscous nature, even at low levels, it can modify food texture. Guar gum is hydrolyzed enzymatically under controlled conditions to create partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG). It has a smaller molecular mass, less viscosity than the original guar gum and is completely water soluble. It is recognized as a prebiotic fiber, having a bland flavour and little physical effect on foods. PHGG enhances the concentration of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria species and also increases the SCFA concentration in the colon [33, 34].

Pectin

Pectin is a polysaccharide present in all fruits and vegetables generally used as a stabilizer, gelling agent or emulsifier. It is mainly found in the peel and pulp of vegetables and fruits, mostly citrus fruits, apples and sugar beets. It is heterogeneous and a highly complex polysaccharide of d-galacturonic acid with a molecular weight of 50,000–150,000 g/mol [35]. The structure of pectin consists of mainly three domains covalently attached one to another, rhamnogalacturonan I (RG I), rhamnogalacturonan II (RG II) and homogalacturonan (HG) [36]. The most abundant pectin polysaccharide is HG and is a linear chain of α (1–4) linked galacturonic acid (GA), which covers about 65% of total pectin. It can be in the free form or esterified with methyl at the carboxyl group at C-6. The other pectin polysaccharide RG I and others are more complex than HG. The RG I represent about 20–35% pectin, consisting of alternating α-d-galacturonic acid and α-l-rhamnosyl residues i.e. [-α-D-GalA-1,2-α-L-Rha-1–4-]n. However, RG II is highly branched and most structured pectin, covering about 10% of total pectin. In native pectin, about 80% of GA is esterified as methyl ester. The degree of esterification (DE) is termed as the proportion of esterified GA group to total GA. Thus, the pectin is categorized as low methoxy pectin (LMP) with DE of less than 50% and high methoxy pectin (HMP) with DE of more than 50%. The major natural pectins are high methoxy pectin (DE, ~ 80%), however, processed food has mainly low methoxy pectin. DE determines the pectin property, as the LMP forms a gel in the presence of divalent ion mainly Ca+2, it can form a gel in a system with low solid content and a wide pH range, whereas HMP forms gel at acidic pH (pH, ~ 3) in aqueous solution with high sugar concentration.

Pectins are not hydrolyzed by digestive enzymes and in the colon, beneficial microbes ferment it and produce SCFAs acetate, butyrate and propionate. It improves the growth of beneficial microbes like Bifidobacteria, Lactobacilli, and Enterococcus. Pectins can also bind the metal in the digestive tract and can prevent its absorption, thus oral administration of pectin removes heavy metals, reduces the absorption of lead and decreases strontium in blood and bone level. They protect against severe diseases like cancer and Alzheimer's [35].

Resistant Dextrin

Dextrin is a general term applied to any starch degradation products obtained after heating starch in the presence of a small amount of moisture and acid. Dextrins can be prepared from any starch and are, commonly classified as yellow dextrin, white dextrin and British gums. Each dextrin is produced by a process like partial hydrolysis (depolymerization), transglycosylation (rearrangement of molecule) and repolymerization [37]. Starch hydrolysis produces a range of varying chain length starch fractions, transglycosylation provides branching and produces highly branched and more soluble polymer. Whereas, repolymerization occurs in the presence of acids at high temperatures and low moisture, providing high molecular mass and a more branched structure [38]. Resistant dextrins (RD) contain short-chain glucose polymers (Glu–Glu–) and are soluble non-viscous fibers. These prebiotics are commonly used for the development of functional food and beverages due to their good water solubility and low viscosity. These are highly resistant to digestive enzymes as they have inaccessible structures, rich in α (1–4) and α (1–6) glycosidic bonds, mainly derived from maize or wheat. They are found to enhance the abundance of Bacteroides but reduce the clostridia in stool, also enhancing SCFAs production [39]. RD facilitates the metabolic parameters in women having polycystic ovary syndrome and enhances calcium and magnesium retention and absorption in the body [40] (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Prebiotic and its application

| Prebiotics | Application | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polydextrose | Greek yoghurt, ice cream and as low-calorie bulking agent in cake |

Reduces calorie, melting time, melting temperature, ice crystal size and decrease Bacteroides Enhance white intensity, glass transition temperature, rheological properties, volatile compounds, mineral absorption, increases bifidobacterial and lactobacilli and improve stool consistency |

[41–43] |

| Soybean oligosaccharides | Yoghurt, health food and pharmaceuticals |

Improve functional and overall quality, reduces fermentation time Promote production of SCFA, and improve gut health |

[44–46] |

| Isomalto-oligosaccharides | Beverages and dairy products |

Fat and sugar replacer, and offer organoleptic functionality Lower down risk of cancer, serum triglyceride, and glycaemic response Increases bifidobacterial and lactobacilli |

[47, 48] |

| Fructo-oligosaccharides | Infant formula, fresh cream cheese, bread, biscuit, cake, pastries, and confectionary products |

Modulate intestinal microbes, and immune system as human milk Sugar and Fat replacer Reduces blood sugar and lipid, and enhance mineral absorption. Inhibit growth of pathogenic microbes, and reduces colon cancer risk |

[49–51] |

| Gluco-oligosaccharides | Ice cream, cake, and yoghurt | Promotebifidobacteria growth, improve stool consistency, increase mineral absorption, and reduces colon cancer risk | [17] |

| Xylo-oligosaccharides | Food and carbonated drinks |

Creation of hydrogels, micro- or nanoparticles, drug delivery systems for treatment, prevention of digestive problem, sugar replacer Improve intestinal microbiota Antioxidative, antimicrobial, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulator properties Reduces blood glucose and cholesterol Enhances mineral absorption |

[18, 52, 53] |

| Inulin | Fat and sugar replacer, emulsifier, thickener, stabilizer |

Improves mouthfeel Decreases acidity, firmness, stickiness, viscosity Lower triacyl glycerol level,increases stool volume, prevent obesity, and immunomodulatory effect |

[23, 54–56] |

| Isomaltulose | Sports and energy drink, dairy products, breakfast cereal, special clinical nutrition feed, malt beverage |

Tooth friendly, promote growth of intestinal microbiota Improve cognitive and sports performance Prevent cancer and cardiovascular disease |

[24] |

| Gentio-ologsaccharides | Coffee, jam, chocolate, beverages |

Improve flavour, stimulate bitter taste like chocolate, and increase water absorption Exceptional prebiotic effect, promote lactobacilli, and bifidobacterial proliferation |

[20, 57] |

| Lactulose | Yoghurt, chocolate, cookies, and cake |

Improve browning and texture Increase count of gut microbes including lactobacilli, and bifidobacteria Increases Mg, Fe, Zn and Ca absorption. Low dose of lactulose used for treatment of constipation in adults and children Control blood glucose level |

[27, 58] |

| Lectoferrin | Cosmetics and pharmaceuticals |

Antimicrobial activity against bacteria, fungi, parasites, and virus Anticancer, anti-oxidant, and anti-inflammatory Prevent diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and anaemia |

[59] |

| Sugar alcohols | Fruit spreads, gum, sweets, ice cream, baked goods, beverage, chewing gum, candy, puddings, pharmaceuticals | Sugar substitute, low glycaemic index and non-cariogenic | [60] |

| Galacto-oligosachharides | Infant formula, bread, yoghurt, juice and beverages |

Stimulate bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, reduces pathogenic bacteria, and improve calcium absorption Prevent constipation, decreases total cholesterol, reduces cancer, and relieve lactose intolerance |

[16] |

| Partially Hydrolyzed Guar Gum | Bread, cookies, yoghurt, noodles, beverage |

High solubility, low viscosity, odourless Decrease plasma triglyceride, cholesterol level, and blood cholesterol Reduces abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome |

[31] |

| Pectin | Jam, jelly, milk dessert and as edible coating material |

Emulsifier, gelling, thickener, and stabilizer property for food Reduces glucose and cholesterol absorption, increase faecal mass, fermented by gut microbiota, anti-cancer, immunomodulatory |

[35, 61] |

| Resistant dextrin | Pharmaceutical, confectionery and in low-calorie foods |

Low viscosity, good water solubility Decreases harmful Clostridium, facilitate growth ofbeneficial bacteria, reduces serum cholesterol, blood triglycerides, cancer and colon disease |

[37] |

Table 2.

| Prebiotics | Structure | Glycosidic bond | Degree of polymerization | Composition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polydextrose |  |

α, β (1 → 6) predominate | 2–20 | Glucose, sorbitol and citric acid | Potato starch, maize starch, corn starch |

| Soybean oligosaccharides |  |

α (1 → 6) | 3–4 | Glucose, fructose, galactose | Soya bean |

| Isomalto-oligosaccharides |  |

α (1 → 6) | 2–8 | α-d-O-glucose | Soy sauce, sake and miso |

| Fructo-oligosaccharides |  |

β (2 → 1) | 2–10 | Fructose, glucose | Lettuce, garlic, chicory, onion, asparagus artichoke, banana, Wheat |

| Gluco-oligosaccharides |  |

α/β-(1 → 6/3/2/1) | 2–10 | Glucose | Starch, cellulose, maltose, sucrose |

| Xylo-oligosaccharides |  |

β (1 → 4) | 2–7 | Xylose | Fruits, vegetable bamboo shoots, honey, milk, rice or wheat straw, corn cob, and hull of cotton seeds |

| Inulin |  |

β (2 → 1) | 3–60 | Fructan | Onion, garlic, chicory, asparagus, artichoke, barley, and wheat |

| Isomaltulose |  |

α (1 → 6) | Disaccharide | Glucose and fructose | Sugar cane juice, honey, beet sugar |

| Gentio-oligosaccharide |  |

β (1 → 6) | 2–10 | Glucose | Honey and rhizomes plant |

| Lactulose |  |

β (1 → 4) | Galactose and fructose | Disaccharide | Whey |

| Lactoferrin | Polypeptide of 703 amino acids | Peptide bond | 703 Amino acids | Amino acids | Cholostrum milk, saliva, tears |

| Sugar alcohols |  |

Hydroxyl group | – | – | Fruits, sweet potato, corn starch |

| Galacto-oligosachharides |  |

β (1 → 3), β (1 → 4) or β (1 → 6) | 3–8 | Galactose | Human milk, bovine milk, chickpeas, beans and lentils |

| Partially hydrolyzed guar gum |  |

β (1 → 4) | About 29 | Mannose and galactose unit | Guar plant |

| Pectin |  |

α (1 → 4) | 100–1000 | Galacturonic acid | Citrus fruit, apple, banana, chick pea, mulberry, dragon fruit, jack fruit |

| Resistant dextrin | Mixture of glucose containing oligosaccharide | α (1 → 2), α (1 → 3), β (1 → 2) and β (1 → 6) | Various | Glucose containing oligosaccharide | Starch (wheat starch, corn starch, potato starch) |

Mechanism of Action of Prebiotics

The mechanism of action of prebiotics is a fascinating interplay between these non-digestible compounds and the intricate ecosystem of the gut microbiome. Prebiotics primarily serve as a source of nutrition for beneficial bacteria residing in the gastrointestinal tract, contributing significantly to the overall health of the host. The easiest way to establish a healthy microbiome or to restore it during dysbiosis is to include prebiotics in our diet. There are several health benefits reported to various prebiotics maintenance of intestinal health, improvements in blood lipid profile, and anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory and antihypertensive properties [7]. The mechanism of action of prebiotics to improve health can be direct (modulating the immune system—pro and anti-inflammatory response) or indirect (substrate for probiotics, production of SCFAs and elimination of pathogens). The gut-associated epithelium is the primary site of action of prebiotics. Prebiotics contribute to the maintenance of intestinal permeability and the regulation of inflammation. The immunological cells may be affected directly or indirectly by prebiotics. The rationale of prebiotics is that they get digested in the large intestine not in the small intestine as we humans lack enzymes for hydrolyzing the complex polymer bonds. The prebiotics is carried by the body intact to the large intestine, where the intestinal flora breaks them down and selectively ferments them to produce specific secondary metabolites. These metabolites can have advantageous effects on the physiological processes of the host, including immunity regulation, pathogen resistance, improved intestinal barrier function, and increased mineral absorption. The prebiotic mechanism of action can be direct or indirect.

The direct mechanism of prebiotics is by directly stimulating the growth of probiotic microbes. Probiotics in the large intestine will interact with the intestinal bacteria to strengthen the bacterial chemical, mechanical, biological, and immunological barriers [63, 64]. Probiotics work with intestinal cells after they enter the intestine to promote mucosal regeneration, increase mucus production, restore intestinal permeability, and preserve the integrity of the intestinal mechanical barrier and mucosal barrier.

Prebiotics generally encourage probiotics to produce secondary metabolites like SCFAs, primarily butyric, propionic, and acetic acids and several antimicrobial peptides. These metabolites can lower the pH of the colon and provide a conducive environment to probiotics and encourage their proliferation and colonisation. A proper pH level in the human gut is necessary to preserve probiotics' capacity to adhere to the surfaces. The SCFA binds to G-Protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) in the intestine and can induce various signalling pathways like Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) resulting in the production of anti-microbial peptides. SCFA also activates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines by modulating the immune cells (T cells/dendritic cells/macrophages) thereby influencing the epithelial cell functions. SCFA can influence intestinal epithelial cell function and preserve the integrity and barrier function.

Prebiotics like fructans are converted to butyric acid which is reported to scavenge Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the gut thereby providing a protective environment to Oxygen-sensitive probiotics. According to reports, the prebiotics of GOS, resistant starch (RS), and inulin-type fructans can break down bile salts and acids by binding to bile acids, decreasing their reabsorption, and speeding up their turnover rate in the intestine [63]. Understanding the mechanisms of action of prebiotics is essential for appreciating their role in promoting a balanced and resilient gut microbiome. As research in this field continues to evolve, it opens avenues for developing targeted interventions to optimize gut health and address various health conditions associated with dysbiosis.

Conclusion

The Codex/FAO/FSSAI has played a leading role in ensuring global access to safe and beneficial food products. One such category gaining approval and attention is prebiotics, owing to their capacity to modulate gut microbiota and the immune system, positioning them as potential candidates for wellness foods and adjuvant therapy. Prebiotic functional foods are associated with numerous health benefits, including anti-diabetic and anti-hypertensive effects, as well as immune enhancement. While these positive effects are promising, it is crucial to emphasize the imperative for more extensive research, particularly involving clinical trials, to unequivocally demonstrate the health impacts of prebiotics. Beyond their health benefits, prebiotics exhibit additional functionalities such as acting as fat substitutes and contributing to the texture and technological properties of food products. Therefore, future research endeavors should strive to provide a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms underlying prebiotic effects as well as explore their diverse technological applications and potential for value addition in the realm of foods. Exploring the area of selective growth of probiotics by emerging prebiotics and their utilization efficiency is an important direction for future development. Consumers are encouraged to make informed choices and embrace products enriched with approved prebiotics to support healthy gut microbiota. As our understanding of the intricate relationship between gut health and overall health deepens, scientific commitment to ensure the safety and efficacy of prebiotic ingredients sets the stage for a healthier future for the Indian population.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.FAO (2002) Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. Joint FAO/WHO working group report on drafting guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food

- 2.Fata GL, Rastall RA, Lacroix C, Harmsen HJM, Mohajeri MH, Weber P, Steinert RE. Recent development of prebiotic research-statement from an expert workshop. Nutrients. 2017;9:1376. doi: 10.3390/nu9121376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Codex Alimentarius Commission (2018) Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme. CODEX Committee on nutrition and foods for special dietary uses, fortieth session, Berlin, Germany, pp 1–14

- 4.Kusar A, Zmitek K, Lahteenmaki L, Raats MM, Pravst I. Comparison of requirements for using health claims on foods in the European Union, the USA, Canada, and Australia/New Zealand. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20:1307–1332. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKeown NM, Fahey GC, Slavin J, van der Kamp JW. Fibre intake for optimal health: How can healthcare professionals support people to reach dietary recommendations? Br Med J. 2022;378:e054370. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2020-054370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussein LA. Novel prebiotics and next-generation probiotics: opportunities and challenges. In: Singh RB, editor. Functional foods and nutraceuticals in metabolic and non-communicable diseases. Elsevier: Academic Press; 2022. pp. 431–457. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosa MC, Carmo MR, Balthazar CF, Guimarães JT, Esmerino EA, Freitas MQ, Silva MC, Pimentel TC, Cruz AG. Dairy products with prebiotics: an overview of the health benefits, technological and sensory properties. Int Dairy J. 2021;117:105009. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2021.105009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putaala H. Polydextrose in lipid metabolism. In: Valenzuela BR, editor. lipid metabolism. Rijeka: Intech Open; 2013. pp. 233–260. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do Carmo MM, Walker JC, Novello D, Caselato VM, Sgarbieri VC, Ouwehand AC, Andreollo NA, Hiane PA, Dos Santos EF. Polydextrose: physiological function, and effects on health. Nutrients. 2016;8:553. doi: 10.3390/nu8090553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Röytiö H, Ouwehand AC. The fermentation of polydextrose in the large intestine and its beneficial effects. Benef Microbes. 2014;5:305–313. doi: 10.3920/BM2013.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glibowski P, Skrzypczak K. Prebiotic and symbiotic foods. In: Grumezescu AM, Holban AM, editors. Microbial production of food ingredients and additives. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2017. pp. 155–188. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thakker C, San KY, Bennett GN. Soybean carbohydrates as a renewable feedstock for the fermentative production of succinic acid and ethanol. In: Brentin RP, editor. Soy-based chemicals and materials. Washington: American Chemical Society; 2014. pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Švejstil R, Musilová Š, Rada V. Raffinose-series oligosaccharides in soybean products. Sci Agric Bohem. 2015;46:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonçalves DA, Teixeira JA, Nobre C. In situ enzymatic synthesis of prebiotics to improve food functionality. In: Kuddus M, Aguilar CN, editors. Value-addition in food products and processing through enzyme technology. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2022. pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molina MS, Larqué E, Torrella F, Zamora S. Dietary fructooligosaccharides and potential benefits on health. J Physiol Biochem. 2009;65:315–328. doi: 10.1007/BF03180584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mei Z, Yuan J, Li D. Biological activity of galacto-oligosaccharides: a review. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:993052. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.993052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng M, van Pijkeren JP, Pan X. Gluco-oligosaccharides as potential prebiotics: synthesis, purification, structural characterization, and evaluation of prebiotic effect. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2023;22:2611–2651. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.13156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Xie Y, Ajuwon KM, Zhong R, Li T, Chen L, Zhang H, Beckers Y, Everaert N. Xylo-oligosaccharides, preparation and application to human and animal health: a review. Front Nutr. 2021;8:731930. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.731930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Althubiani AS, Al-Ghamdi SB, Qais FA, Khan MS, Ahmad I, Malak HA. Plant-derived prebiotics and its health benefits. In: Khan MSA, Ahmad I, Chattopadhyay D, editors. New look to phytomedicine advancements in herbal products as novel drug leads. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2019. pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia W, Sheng L, Mu W, Shi Y, Wu J. Enzymatic preparation of gentiooligosaccharides by a thermophilic and thermostable β-glucosidase at a high substrate concentration. Foods. 2022;11:357. doi: 10.3390/foods11030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson JL, Erickson JM, Lloyd BB, Slavin JL. Health effects and sources of prebiotic dietary fiber. Curr Dev Nutr. 2018;2:1–8. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzy005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barclaya T, Ginic-Markovica M, Cooperb P, Petrovsk N. Inulin—a versatile polysaccharide with multiple pharmaceutical and food chemical uses. J Excipients Food Chem. 2016;1:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mudgil D. The interaction between insoluble and soluble fiber. In: Samaan RA, editor. Dietary fiber for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2017. pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shyam S, Ramadas A, Chang SK. Isomaltulose: recent evidence for health benefits. J Funct Foods. 2018;48:173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Souza WF, Almeida FL, de Castro RJ, Sato HH. Isomaltulose: from origin to application and its beneficial properties-a bibliometric approach. Food Res Int. 2022;155:111061. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shendurse AM, Khedkar . Lactose. In: Caballero B, Finglas P, Toldrá F, editors. Encyclopedia of food and health. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2016. pp. 509–516. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karakan T, Tuohy KM, Solingen GJ. Low-dose lactulose as a prebiotic for improved gut health and enhanced mineral absorption. Front Nutr. 2021;8:672925. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.672925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozer B. Natural anti-microbial systems: lactoperoxidase and lactoferrin. In: Batt CA, Lou TM, editors. Encyclopedia of food microbiology. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2014. pp. 930–935. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Artym J, Zimecki M. Antimicrobial and prebiotic activity of lactoferrin in the female reproductive tract: a Comprehensive Review. Biomedicines. 2021;9:1940. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9121940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupont TL. Donor milk compared with mother’s own milk. In: Ohls R, Maheshwari A, editors. Hematology, immunology and infectious disease: neonatology questions and controversies. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019. pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grembecka M. Sugar alcohols—their role in the modern world of sweeteners: a review. Eur Food Res Technol. 2015;241:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00217-015-2437-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petković M. Alternatives for sugar replacement in food technology: formulating and processing key aspects. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niv E, Halak A, Tiommny E, Yanai H, Strul H, Naftali T, Vaisman N. Randomized clinical study: partially hydrolyzed guar gum (PHGG) versus placebo in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr Metab. 2016;13:10. doi: 10.1186/s12986-016-0070-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kapoor MP, Koido M, Kawaguchi M, Timm D, Ozeki M, Yamada M, Mitsuya T, Okubo T. Lifestyle related changes with partially hydrolyzed guar gum dietary fiber in healthy athlete individuals–a randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled gut microbiome clinical study. J Funct Foods. 2020;72:104067. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blanco-Pérez F, Steigerwald H, Schülke S, Vieths S, Toda M, Scheurer S. The dietary fiber pectin: health benefits and potential for the treatment of allergies by modulation of gut microbiota. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021;21:43. doi: 10.1007/s11882-021-01020-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ropartz D, Ralet MC. Pectin structure. In: Kontogiorgos V, editor. Pectin: technological and physiological properties. Berlin: Springer; 2020. pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egharevba HO. Chemical properties of starch and its application in the food industry. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhen Y, Zhang T, Jiang B, Chen J. Purification and characterization of resistant dextrin. Foods. 2021;10:185. doi: 10.3390/foods10010185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hobden MR, Commane DM, Guérin-Deremaux L, et al. Impact of dietary supplementation with resistant dextrin (NUTRIOSE®) on satiety, glycaemia, and related endpoints, in healthy adults. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:4635–4643. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02618-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu Q, Lu Y, Hu F, He S, Xu X, Niu Y, Zhang H, Li X, Su Q. Resistant dextrin reduces obesity and attenuates adipose tissue inflammation in high-fat diet-fed mice. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17:2611–2621. doi: 10.7150/ijms.45723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumari A, Arora S, Singh AK, Choudhary S. Development of an analytical method for estimation of neotame in cake and ice cream. LWT. 2016;70:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.02.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balthazar CF, Silva HA, Vieira AH, et al. Assessing the effects of different prebiotic dietary oligosaccharides in sheep milk ice cream. Food Res Int. 2017;91:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Paulo FD, de Araújo FF, Neri-Numa IA, Pastore GM. Prebiotics: trends in food, health and technological applications. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2019;93:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2019.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bharathi S (2019) Functional effects of soy-raffinose on the quality parameters of yogurt. Doctoral dissertation, University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma. https://hdl.handle.net/11244/326826

- 45.Elango D, Rajendran K, Van der Laan L, et al. Raffinose family oligosaccharides: Friend or foe for human and plant health? Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:829118. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.829118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Y, Li C, Shan Z, Yin S, Wang Y, et al. In vitro fermentability of soybean oligosaccharides from wastewater of tofu production. Polymers. 2022;14:1704. doi: 10.3390/polym14091704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singla V, Chakkaravarthi S. Applications of prebiotics in food industry: a review. Food Sci Technol Int. 2017;23:649–667. doi: 10.1177/1082013217721769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sorndech W, Nakorn KN, Tongta S, Blennow A. Isomalto-oligosaccharides: recent insights in production technology and their use for food and medical applications. LWT. 2018;95:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.04.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang X, Zeng D, Li C, Yu W, Xie G, Zhang Y, Lu W. Therapeutic potential and mechanism of functional oligosaccharides in inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2023;12:2135–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2023.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speranza B, Campaniello D, Monacis N, Bevilacqua A, Sinigaglia M, Corbo MR. Functional cream cheese supplemented with Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis DSM 10140 and Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 20016 and prebiotics. Food Microb. 2018;72:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen D, Yang X, Yang J, Lai G, Yong T, Tang X, Shuai O, Zhou G, Xie Y, Wu Q. Prebiotic effect of fructooligosaccharides from Morinda officinalis on Alzheimer’s disease in rodent models by targeting the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:403. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin SH, Chou LM, Chien YW, Chang JS, Lin CI. Prebiotic effects of xylooligosaccharides on the improvement of microbiota balance in human subjects. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5789232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gupta PK, Agrawal P, Hegde P, Shankarnarayan N, Vidyashree S, Singh SA, Ahuja S. Xylooligosaccharide—a valuable material from waste to taste: a review. J Environ Res Dev. 2016;10:555–563. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer D, Bayarri S, Tárrega A, Costell E. Inulin as texture modifier in dairy products. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25:1881–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Żbikowska A, Szymańska I, Kowalska M. Impact of inulin addition on properties of natural yogurt. Appl Sci. 2020;10:4317. doi: 10.3390/app10124317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, Cao L, Ji J, Shen M, Gao J. Modulation of Human Gut Microbiota In Vitro by Inulin‑Type Fructan from Codonopsis pilosula Roots. Ind J Microbiol. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s12088-023-01185-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kothari D, Goyal A. Gentio-oligosaccharides from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1426 dextransucrase as prebiotics and as a supplement for functional foods with anti-cancer properties. Food Funct. 2015;6:604–611. doi: 10.1039/C4FO00802B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nooshkam M, Babazadeh A, Jooyandeh H. Lactulose: properties, techno-functional food applications, and food grade delivery system. Trends Food Sci. 2018;80:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janczuk A, Brodziak A, Czernecki T, Król J. Lactoferrin—the health-promoting properties and contemporary application with genetic aspects. Foods. 2022;12:70. doi: 10.3390/foods12010070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mudgil D. Partially hydrolyzed guar gum: preparation and properties. In: Gutiérrez T, editor. Polymers for food applications. Cham: Springer; 2018. pp. 529–549. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vanitha T, Khan M. Role of pectin in food processing and food packaging. In: Masuelli M, editor. Pectins-extraction, purification, characterization and applications. London: IntechOpen; 2019. pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen W, Zhang T, Ma Q, Zhu Y, Shen R. Structure characterization and potential probiotic effects of sorghum and oat resistant dextrins. Foods. 2022;11:1877. doi: 10.3390/foods11131877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pujari R, Banerjee G. Impact of prebiotics on immune response: from the bench to the clinic. Immunol Cell Biol. 2021;99:255–273. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.You S, Ma Y, Yan B, Pei W, Wu Q, Ding C, Huang C. The promotion mechanism of prebiotics for probiotics: a review. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1000517. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]