Summary

The early appearance of broadly-neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) in serum is associated with spontaneous hepatitis C virus (HCV) clearance, but to date, the majority of bNAbs have been isolated from chronically-infected donors. Most of these bNAbs use the VH1–69 gene segment and target the envelope glycoprotein E2 front-layer. Here, we performed longitudinal B cell receptor (BCR) repertoire analysis on an elite neutralizer who spontaneously cleared multiple HCV infections. We isolated 10,680 E2-reactive B cells, performed BCR sequencing, characterized monoclonal B cell cultures, and isolated bNAbs. In contrast to what has been seen in chronically-infected donors, the bNAbs used a variety of VH-genes and targeted at least three distinct E2 antigenic sites, including sites previously thought to be non-neutralizing. Diverse front-layer-reactive bNAb lineages evolved convergently, acquiring breadth-enhancing somatic mutations. These findings demonstrate that HCV clearance-associated bNAbs are genetically diverse and bind distinct antigenic sites that should be the target of vaccine-induced bNAbs.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, HCV, neutralizing epitopes, monoclonal antibodies, broadly neutralizing antibodies, B cells, BCR sequencing, antibody evolution, vaccine

Graphical Abstrac

ETOC BLURB

Most bNAbs from chronically HCV-infected people use the VH1–69 gene segment and target the envelope glycoprotein E2 front-layer. Ogega et al. isolate bNAbs from an elite neutralizer who spontaneously cleared HCV. These bNAbs use a variety of VH-genes and target three E2 antigenic sites, including sites previously thought to be non-neutralizing. These sites should be the target of vaccine-induced bNAbs.

Introduction

No vaccine is currently available to prevent hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and chronic infection can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma.1,2 Despite the availability of direct-acting antivirals to treat HCV, the incidence of new HCV infections continues to rise.3,4 Of those infected with HCV, approximately 25% spontaneously clear the infection without treatment and these individuals have an 80% chance of clearing subsequent reinfections, typically with lower peak viremia and shorter duration of infection.5 We and others have previously shown that spontaneous clearance of infection is associated with the early emergence of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs), which target the HCV envelope E2 glycoprotein and block infection by genetically and antigenically diverse viral variants.6–9 We also have shown that bNAbs play a direct role in viral clearance in some individuals.10 Additionally, infusion of bNAbs is protective against HCV infection in animal models.11–14 With this knowledge, it is plausible that we should be able to design a bNAb-inducing vaccine that protects against persistent HCV infection. However, a major challenge for vaccine development is the lack of a comprehensive understanding of the epitopes targeted by bNAbs mediating natural clearance of infection, and the developmental pathways giving rise to these bNAbs.

In a recent study, Weber et al.15 used a truncated E2 glycoprotein probe to isolate B cells from four individuals who had been chronically infected with HCV for 6 to >15 years. They captured almost exclusively E2 front layer-reactive bNAbs encoded by the VH1–69 gene segment. Those data confirmed prior studies showing that VH1–69 usage correlated with broad HCV neutralization.16–18 The VH1–69 gene segment is also frequently used by bNAbs specific for HIV and Influenza, likely because it facilitates interactions with hydrophobic patches on receptor-binding domains.15,19–25 In addition to the VH1–69 gene segment, several human anti-HCV bNAbs also use the D2–15 D-gene, which encodes two cysteine residues that form a disulfide motif at the tip of CDRH3.20,26 Due to the limited number of bNAbs isolated to date, the extent to which VH1–69 or D2–15 gene usage and E2 front layer reactivity are required for broad HCV neutralization is unknown. It is particularly unclear whether these V and D-genes or front layer epitopes predominate for bNAbs of persons capable of natural HCV clearance. These are critical questions for vaccine development since they identify protective epitopes that should be targeted by a vaccine. Furthermore, exclusive reliance on single V or D-gene segments would restrict the genetic pathways available for bNAb induction by vaccines, while also limiting the value of most animal models, including mice, for vaccine development, since they do not encode IGHV1–69 or IGD2–15 orthologs.

Here, we used a mixture of genetically and antigenically diverse E2 ectodomain proteins to isolate E2-reactive B cells from the longitudinally-collected blood of an elite neutralizer (EN), defined as a person ranked in the top 5% of our cohort based on the HCV neutralizing breadth of their plasma. We also previously demonstrated that neutralizing antibodies mediated clearance of infection in this individual.10,27 We performed B cell receptor sequencing (BCR-seq) at time points from initial infection through multiple viral clearance events, characterized monoclonal B cell cultures, isolated E2-reactive mAbs, and identified bNAbs. We characterized V and D-gene usage of these bNAbs and mapped their epitopes on E2, identifying previously described and additional neutralizing epitopes on the back layer and β-sandwich regions of E2. We solved the structures of representative E2-bNAb complexes, including crystal structures of non-VH1–69 bNAb-E2 complexes. We found evidence of the early emergence of bNAbs targeting at least three distinct E2 antigenic sites, with ongoing maturation over time and convergent evolution of multiple bNAb lineages using diverse VH-gene segments. Overall, these studies highlight the diversity and plasticity of the human bNAb response against HCV, while identifying key bNAb-E2 interactions associated with broad neutralizing activity and natural clearance of HCV infection.

Results

Elite neutralizer plasma is broadly neutralizing against genetically and antigenically diverse HCVpp.

The Baltimore Before and After Acute Study of Hepatitis (BBAASH) is a prospective, longitudinal cohort of people who inject drugs, with monthly blood collection from before the time of infection through spontaneous viral clearance or the transition to chronic infection.28 To identify a participant for exhaustive BCR repertoire analysis and mAb isolation, we screened neutralizing breadth of early-infection plasma samples from 63 BBAASH participants using a panel of 17 HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpp). Participants with clearance of infection (n=21) were sampled at a median of 275 days post-infection (dpi), while participants with persistent infection (n=42) were sampled at a median of 238 dpi. The HCVpp panel consists of a recently described antigenically diverse set of 15 HCVpp spanning four tiers of increasing neutralization resistance29, as well as 2 additional highly neutralization-resistant (Tier 4) variants (UKNP2.4.1 and UKNP6.1.1), with the full panel also representing HCV genotypes 1–6. We observed a broad spectrum of neutralizing breadth with no clear distinction between those with naturally cleared or persistent infection (Figure 1A). We designated the 10% of participants with the greatest plasma-neutralizing breadth as elite neutralizers (EN). The subject with the greatest neutralizing breadth among all EN, designated subject C110, naturally cleared three infections without treatment, and we previously demonstrated that neutralizing antibodies played a direct role in the clearance of their primary infection.10 Plasma from C110 displayed a pattern of relative neutralizing activity across the HCVpp panel that was representative of the EN subset of BBAASH participants (Figure 1B). Moreover, HEPC74, a bNAb that has been extensively characterized17,26, was previously isolated from this subject by human hybridoma technology. To capture the full bNAb repertoire, we selected a timepoint 2,178 dpi for mAb isolation. By that time, C110 had cleared 3 infections without antiviral treatment. Additionally, 4 longitudinal time points throughout the course of infection were selected for BCR-seq of E2-reactive B cells to characterize bNAb induction and evolution (Figure 1C). Plasma from all five time points displayed broad neutralizing activity, beginning during primary infection (Figure 1D), as has been shown for other cleared infections.7 In summary, by screening the BBAASH cohort with a diverse panel of 17 HCVpp, we identified an EN with spontaneous clearance of multiple HCV infections and broadly neutralizing plasma that was representative of other EN in the cohort.

Figure 1. Elite neutralizer plasma is broadly neutralizing against genetically and antigenically diverse HCVpp.

(A) Neutralizing breadth of early infection plasma from 63 BBAASH participants with either spontaneous clearance of infection (n=21, prefix “C”) or persistence of infection (n=42, prefix “P”). The 10% of participants with the greatest neutralizing breadth (n=6) were designated elite neutralizers (EN). (B) Neutralizing activity of 6 EN against each of 17 Tier 1 (sensitive) to Tier 4 (resistant) HCVpp. Values for subject C110 are indicated in red. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Viral RNA levels of subject C110 demonstrating spontaneous clearance of 3 infections (delineated by distinct colors). The timepoint used for mAb isolation (D2178) is indicated (arrow) along with the four timepoints used for BCR-seq analysis (red dots). (D) C110 plasma neutralizing breadth at the 5 timepoints used for BCR-seq and mAb analysis. Neutralization was measured in duplicate in one experiment.

E2-reactive BCRs show increased somatic mutation and longer CDRH3 sequences.

We used a mixture of 3 antigenically diverse subtype 1a and 1b soluble E2 ectodomain proteins (sE2), designated 1b21, 1a157, and 1b09, as antigen bait to capture and sort single E2-reactive mature class-switched B cells (CD19+, CD10-, CD3-, IgM-, IgD-, sE2+; Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 1), as previously described.30 B cells sorted from PBMCs isolated 2178 dpi (D2178) were cultured at limiting dilutions from 20 to 1 B cell(s) per well and stimulated with recombinant IL-2, IL-21, and irradiated CD40L-expressing fibroblasts. Culture supernatants were tested for the production of human IgG and the presence of IgG that was reactive with each of the three E2 proteins. IgG production was detected in all wells cultured at 20 B cells per well (5/5), 85% (92/408) of wells with 4 B cells, 58% (188/324) of wells with 2 B cells, and 26% (70/270) of wells with 1 B cell (Figure 2B). Supernatants from 2 B cells per well cultures reacted with 1b21, 1a157, and 1b09 sE2 at frequencies of 42/324 wells (13%), 100/324 wells (31%), and 105/324 wells (32%), respectively. Supernatants from 1 B cell per well cultures reacted with 1b21, 1a157, and 1b09 sE2 at frequencies of 13/270 wells (5%), 58/270 wells (21%), and 34/270 wells (13%), respectively (Figure 2B). Of the 259 IgG positive, 2 or 1 B cell supernatants, 64% were reactive with only 1 E2 variant, 22% were cross-reactive with 2 variants, and 9% were cross-reactive with all three E2 variants (Figure 2C). We RT-PCR amplified and sequenced 56 pairs of heavy and light chain variable sequences, from 2 or 1 B cell cultures that were cross-reactive with at least two of three E2 proteins. Sequences from one well were discarded because Sanger sequencing demonstrated mixed peaks in the heavy chain sequence, but sequencing of the remaining 55 wells produced single peaks at each heavy chain nucleotide position, confirming that IgG in each culture arose from the proliferation of a single monoclonal population. Taken together, utilization of a mixture of three E2 proteins as bait to isolate E2-reactive B cells, followed by in vitro stimulation and testing of supernatants for IgG and E2 reactivity, allowed the sensitive and robust selection and sequencing of E2 cross-reactive, authentically paired heavy and light chains.

Figure 2. BCRs show E2 cross-reactivity, increased somatic mutation, and longer CDRH3 sequences.

(A) E2-reactive B cell staining with a mixture of three antigenically distinct soluble E2 proteins. (B) B cells cultured at varying cell density, with frequency (%) of wells positive for human IgG or reactive with each E2 variant. (C) Frequency (%) of IgG positive 2 or 1 B cell supernatants reactive with each E2 variant or cross-reactive with multiple E2 variants. (D) CDRH3 lengths of E2-nonreactive or longitudinal E2-reactive BCRs or mAbs. (E) CDRL3 lengths of E2-nonreactive or longitudinal E2-reactive BCRs or mAbs. (F) VH-gene nucleotide identity to inferred germline sequences. (G) VK or VL-gene nucleotide identity to inferred germline sequences. For D-G, each dot represents an individual BCR sequence. Distribution is shown via violin plot, with horizontal lines indicating medians. For D-G, statistical comparisons were made using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn post-hoc test with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction applied for multiple comparisons. **** p<0.0001; *** p<0.001, ** p<0.01, * p<0.05. See also Figure S1.

E2-reactive and nonreactive class-switched, mature B cells were also sorted from PBMCs isolated at 279, 540, 1267, and 1842 dpi, and subjected to BCR-seq. E2-nonreactive BCR sequences from all the time points were pooled for analysis and E2-reactive sequences were analyzed separately for each time point. These sequences, along with sequences of the 55 mAbs, were analyzed for the presence of somatic mutations, CDR3 lengths, and V or D gene usage. Relative to E2-nonreactive B cells, there was a trend toward increasing CDRH3 length over time that was statistically significant on d1267 (p = 0.01) (Figure 2D). There was no statistically significant difference in light chain CDR3 lengths (Figure 2E). In comparisons of somatic mutation frequencies, defined as BCR nucleotide sequence identity to inferred germline V-gene sequences, there were multiple statistically significant differences. Relative to E2 negative BCRs, d1267 (p < 0.0001), d1842 (p = 0.0008), and d2178 (mAbs; p < 0.0001) BCRs displayed increased somatic mutation frequencies (Figure 2F). Both heavy and light chains also showed a general trend of increasing somatic mutation over time (Figure 2F-G). Of note, among the 55 mAbs, the median (range) VH-gene nucleotide identity to germline was relatively high at 93.4% (87.9 – 99.0%). Overall, relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs, we observed increased E2-reactive CDRH3 length and increased somatic mutation frequencies in E2-reactive BCR heavy and light chains that increased over time.

VH1–69 and D2–2/D2–15 usage favor broad neutralizing activity but are not required.

Sequence analysis of the 55 mAb heavy chains revealed 16 different VH gene segments. VH1–69 was the most frequent, found in 12 of the 55 mAbs (22%), followed by VH1–18, which was found in 9 of 55 mAbs (16%).

We also compared the V-gene usage of longitudinal E2-reactive and nonreactive BCRs. There was a trend towards higher usage of the VH1–69 gene segment in E2-reactive BCRs from all time points relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs, and this difference was statistically significant for d1267 (p = 0.0004) (Figure 3A and Supplemental Figure 2). Additionally, E2-reactive BCRs on d1267 utilized VK4–1 more frequently (p = 0.001) and E2-reactive BCRs on day 1842 used VK1–33 less frequently (p = 0.001) relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs (Figure 3B and Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3. VH1–69 and D2–2/D2–15 usage favor broad neutralizing activity but are not required.

Frequency of usage of VH (A) or VK/VL (B) gene segments among E2-nonreactive or E2-reactive BCRs. Only V-genes used by at least one mAb are shown here, with the remainder in Supplemental Figure 2. Statistical significance is denoted only for E2-reactive BCRs relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs. * p<0.05 using Fisher’s exact test with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons. (C) Neutralizing breadth of 55 E2-reactive mAbs measured using the panel of 17 HCVpp. (D) Neutralizing breadth of mAbs (# of 17 HCVpp neutralized) segregated by VH-gene usage. Each point represents one mAb, with the number of mAbs encoded by each VH-gene (n) indicated. (E) Neutralizing breadth of mAbs (# of 17 HCVpp neutralized) segregated by D-gene usage, with the number of mAbs encoded by each D-gene (n) indicated. NR=not resolved. (F) Neutralizing breadth of mAbs using both VH1–69 and D2–2/D2–15, either, or neither. ns=not significant, * p<0.05 by Kruskal Wallis test for non-normally distributed data, adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli method. In D-F, dashed line indicates neutralization of 9 HCVpp, the threshold for bNAb designation. Solid horizontal lines indicate medians. Neutralization values are the average of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. See also Figures S2-3.

Next, we synthesized immunoglobin variable sequences of the 55 sequenced mAbs and cloned them into human IgG1, Ig Kappa, or Ig Lambda expression plasmids, co-expressing authentically paired heavy and light chains in human embryonic kidney cells to generate IgG1 isotype mAbs, which were designated hepatitis C antibodies (hcabs). We measured the neutralizing breadth of these mAbs using the previously described panel of 17 HCVpp. The majority neutralized tier 1 (i.e., highly sensitive) HCVpp, and 29 mAbs (53%) neutralized 9 or more HCVpps, which is the threshold that we use to define bNAbs (Figure 3C). These 29 bNAbs utilized a wide range of VH gene segments: VH1–69 (9 mAbs), VH1–18 (5 mAbs), VH1–46, VH1–3, VH3–20, VH3–23, and VH4–34 (2 mAbs each), and VH3–74, VH3–48, VH3–74, and VH4–30 (1 mAb each) (Figure 3D). The three most broadly reactive bNAbs (hcab43, hcab60, and hcab05) each neutralized 17 of the 17 HCVpps and utilized VH1–69, VH3–20, or VH4–30 gene segments, respectively (Figure 3D).

We previously identified two cysteine residues that form a disulfide bond motif in CDRH3 as another commonly observed feature of HCV bNAbs.26 Two cysteine residues are encoded by members of the IGHD2 gene family, either D2–2 or D2–15. Of the 55 mAbs, 9 (16%) used D2–2 or D2–15 gene segments and 8 of these mAbs were broadly neutralizing (Figure 3E). However, 21 other bNAbs used a wide range of other D gene segments with the 3 most potent bNAbs (neutralizing all 17 HCVpp) encoded by D3–10, D4–17, or D6–13 (Figure 3E). We then investigated whether VH1–69 or D2–2/D2–15 usage predicted broadly neutralizing activity. Broad neutralizing activity was observed for all 4 mAbs that used both VH1–69 and D2–2/D2–15, 6 of 9 VH1–69 mAbs that did not use D2–2/D2–15, 4 of 5 D2–2/D2–15 mAbs that did not use VH1–69, and 15 of 37 mAbs that did not use VH1–69 or D2–2/D2–15 (Figure 3F). Overall, we concluded that of all E2-reactive B cells, approximately 16% expressed bNAbs. E2-reactive mAbs that use VH1–69 and/or D2–2/D2–15 are likely to be bNAbs. However, we also observed that the majority of HCV bNAbs (15 of 29), including two of the three most potent bNAbs, utilized alternative VH and D gene segments, indicating that broad neutralization does not require VH1–69 or D2–2/D2–15 usage.

To determine whether E2 binding affinities differed significantly between bNAbs and non-bNAbs, we performed ELISAs binding assays with all isolated antibodies and 1a157, 1b09, and 1b21 E2 glycoproteins. We calculated 50% effective concentration (EC50) values from these binding curves as an estimate of the relative binding affinity of the mAbs. We saw no significant difference between bNAb and non-bNAb EC50 values measured with 1a157 or 1b21 E2 glycoproteins, while bNAb EC50 values measured with the 1b09 E2 glycoprotein were somewhat lower than non-bNAb EC50 values (Supplemental Figure 3). Similar to a prior study31, these data indicate that broad neutralization was not predominantly driven by binding affinity.

HCV bNAbs target conserved front layer and additional epitopes on the E2 protein.

To determine the epitope specificity of isolated bNAbs, we first measured the loss of ELISA binding to sE2 proteins with multiple substitutions in the front layer of variant 1a157 E2 (1a157 FRLY KO) or in the antigenic site 412 (AS412) epitope (1a157 AS412 KO), proteins designed to abrogate binding of previously described front layer- or AS412-reactive bNAbs while preserving other conformational epitopes32 (Figure 4A). In these experiments, mAb binding to mutant proteins was calculated relative to binding to wild-type 1a157 E2 protein. To aid the interpretation of these results, we also mapped 6 previously described HCV mAbs with known binding sites. These mAbs were HEPC74, AR3A, HEPC108 (E2 front layer; antigenic region 317,33,34), HC-1 (E2 front layer; Domain B35), HC84.26 (E2 front layer; Domain D36), AR1B (E2 back layer; antigenic region 1), HCV1 (AS41237).

Figure 4. HCV bNAbs target at least three major antigenic sites on the E2 protein.

(A) bNAbs were segregated based on >50% loss of binding to E2 with multiple mutations in the front layer (FRLY KO) or in the AS412 epitope (AS412 KO), relative to binding to wild-type E2 protein. Six reference mAbs (bold) with known binding epitopes as well as previously characterized C110 bNAb HEPC74 were included as controls. Curves were fit and area under the curve (AUC) was calculated from binding of 5-fold serial dilutions of each mAb, performed in duplicate (B) Data from Bio-Layer Interferometry epitope binning experiments using 17 hcabs and 5 reference antibodies (italicized). Numbers indicate the percentage binding of second mAb in the presence of the first mAb compared to binding of un-competed second mAb. mAbs were judged to compete for the same antigenic site if the maximum binding of the second mAb was reduced to <30% of its un-competed binding (black boxes with white numbers). The mAbs were considered non-competing if the maximum binding of the second mAb was >60% of its un-competed binding (white boxes with red numbers). Gray boxes with black numbers indicate an intermediate phenotype (competition resulted in between 30% and 60% of un-competed binding). Dashed lines in red (contains FRLY reference mAbs), dark blue (contains a β-sheet reference mAb), and green (contains no reference mAbs) indicate three major competition groups. The light blue dashed line indicates a minor antigenic group that partially overlaps with the FRLY and β-sheet antigenic groups. A reference bNAb HCV1 is a single member of the AS412 competition group, indicated by yellow dashed lines.

We first grouped these mAbs into front layer-reactive (FRLY) and not front layer-reactive (non-FRLY) groups based on loss of binding to the 1a157 FRLY KO E2 protein. All reference mAbs behaved as expected in this analysis. Of the 25 hcabs that were successfully mapped, 7 (28%) targeted the front layer, 13 (52%) targeted other epitopes on E2, and 5 (20%) gave ambiguous results (Figure 4A). From these data, we concluded that hcabs targeted both FRLY and non-FRLY sites.

To determine which antigenic regions of the E2 glycoprotein are targeted by the non-FRLY mAbs and ambiguous mAbs, we performed E2-binding competition experiments using BioLayer interferometry (Figure 4B). We also included a panel of reference antibodies with known epitope-specificity in this analysis. These mAbs were HEPC74, HEPC108, AR3C (E2 front layer; antigenic region 317,33,34), HEPC46 (E2 β-sandwich; antigenic region 117), and HCV1 (AS41237). Hcabs 41, 42, 57, 60, and 61 did not bind to biotinylated 1a157 E2 in this competition assay and were excluded from the analysis. Consistent with the FRLY KO binding ELISAs, six bNAbs (hcab3, hcab15, hcab43, hcab55, hcab64, hcab71) competed for binding with each other and with FRLY reference mAbs. In the non-FRLY group, four mAbs (hcabs 7, 22, 35, and 44) competed with previously structurally characterized non-neutralizing mAb HEPC46, which targets the β-sandwich antigenic region26, and three mAbs (hcabs 48, 27, and 17) competed for binding to a front layer/ β-sandwich overlapping antigenic region. The remaining five non-FRLY bNAbs (hcabs 5, 22, 23, 31, and 40) bound to a region of E2 distinct from the β-sandwich or FRLY antigenic regions.

Structural analysis reveals conserved bNAb-E2 interactions.

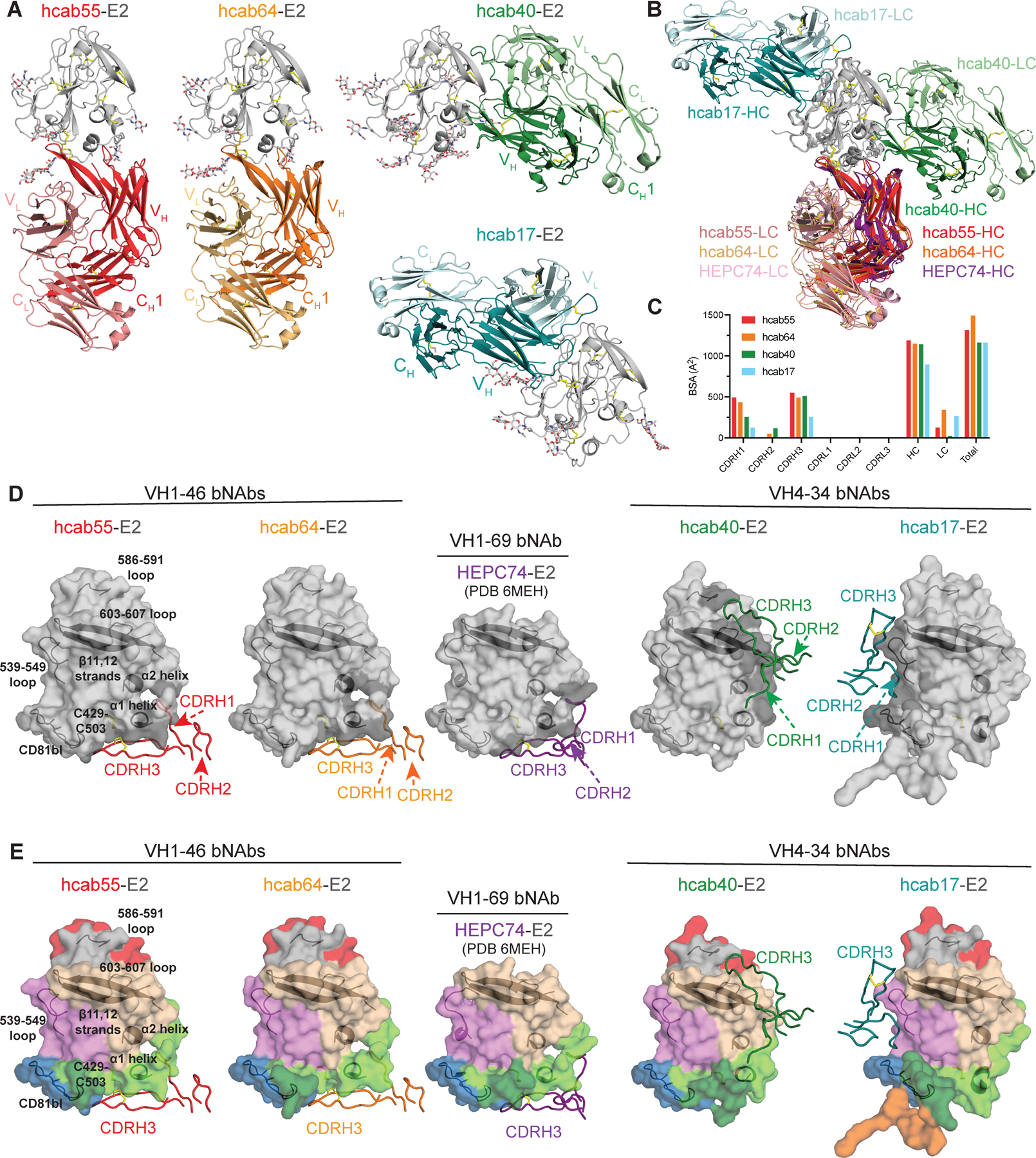

To verify the epitope specificity of the non-VH1–69 bNAbs, we determined crystal structures of hcab55 and hcab64 (FRLY bNAbs), as well as hcab40 (a non-FRLY bNAb) and hcab17 (a non-FRLY non-neutralizing mAb) in complex with E2 ectodomains (E2ecto) (Supplemental Table 1). Crystal structures of E2 complexed with hcab55 and hcab64 (two VH1–46-encoded bNAbs) as well as hcab40 (a VH4–34-encoded bNAb) and hcab17 (a VH4–34-encoded mAb) represent X-ray structures of non-VH1–69 bNAb/mAb-E2 complexes (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Crystal structures of hcab55-E2, hcab64-E2, hcab40-E2, and hcab17-E2 complexes reveal neutralizing epitopes of non-VH1–69 HCV bNAbs.

(A) Crystal structures of E2 (gray, N-glycans shown as sticks and disulfide bonds shown as yellow sticks) in complex with hcab55 (red), hcab64 (orange), hcab40 (green), and hcab17 (cyan) Fabs. (B) Superposition of E2 (gray) in complex with hcab55 (red), hcab64 (orange), hcab40 (green), and hcab17 (cyan), and HEPC74 (PDB 6MEH) (purple) Fabs structures. Structures were superimposed on the E2 head domains. Disulfide bonds are shown as yellow sticks. (C) Comparison of buried surface areas (BSAs). (D) Heavy-chain CDR (CDRH) loops of hcab55, hcab64, hcab40, hcab17, and HEPC74 (PDB 6MEH) Fabs mapped onto the E2 surface. CDRH loops are colored as in (A), and HC interacting residues are colored in dark gray on the E2 surface. Epitopes (surface representation) were defined as residues in E2 containing an atom within 4 Å of the bound Fab. The location of α1-helix, α2-helix, ß11,12-strands, CD81bl, loop 539–549, loop 586–591, and loop 603–607 in E2 are indicated by black cartoon representations, and the C429–C503 disulfide bond is indicated by yellow sticks. (E) Comparison of the CDRH loop positions in E2 complex structures with hcab55, hcab64, hcab40, and HEPC74. E2 structures are shown as surface representation and CDRHs as tubes. CDRH loops are colored as in (A), and important features of E2 and the position of CDRH3 are indicated. E2 surfaces are colored by structural components: HVR1, orange; AS412, dark green; front layer, light green; VR2, red; β sandwich, violet; CD81bl, blue; VR3, gray; back layer, tan. See also Figures S4-5, Tables S1-3.

The structures of the two VH1–46 bNAbs, hcab55 and hcab64, were similar to the previously described crystal structure of VH1–69 bNAb HEPC74, which was also isolated from subject C110. Hcab55, hcab64, and HEPC74 share 22 interface residues that are almost exclusively located in the FRLY of E2; many of these residues are highly conserved across HCV genotypes (Supplemental Table 2). As found for other front-layer-reactive bNAbs, both VH1–46 bNAbs contact E2 primarily by VH residues, burying 1,188 or 1,148 Å2 (91% or 77% of the total Fab buried surface area, BSA) for hcab55 and hcab64, respectively (Figure 5C). The majority of hcab55 and hcab64 contacts with E2 involve CDRH1 and CDRH3. CDRH2, which can play an important role in the recognition of hydrophobic residues in the E2 front layer20,26,38, plays a minimal role among the two VH1–46 bNAbs structurally characterized in this study.

Although they are encoded by different VH-genes, hcab55 and hcab64 (VH1–46 bNAbs) and HEPC74 (VH1–69 bNAb) utilize similar approach angles (Figure 5B) to recognize the overlapping epitopes in the E2 FRLY (Figure 5D). A similar approach angle of three bNAbs (Figure 5E) is likely a result of the straight conformation of disulfide bridge-containing CDRH3 loops of bNAbs that interact with shared E2 contact residues in the FRLY and CD81 binding loop (Figure 5B). This similar binding orientation between HEPC74 and two VH1–46 bNAbs places the CDRH1 loop of these bNAbs in a similar position near the N terminus of the E2 α1 helix (Figure 5D) and CDRH3 loops near the C429 residue in the front layer (Figure 5D-E). E2 residues hydrogen bonded by hcab55, hcab64, and HEPC74 included C429 and N448 (bound by shared D- or VH-gene germline residues C100 or T28, respectively), K446 (bound by shared somatic substitution I30), D431 (bound by junctional residues A/G/K98), and T435 (bound by either germline residue Y32 in HEPC74 or T28 in hcab55 and hcab64) (Supplemental Figure 4A-B). The key interacting residues identified by the structural analysis were consistent with mapping data obtained using E2 domain knockouts and binding competition assays (Figure 4).

The structure of VH4–34/D2–15 encoded hcab17 in complex with E2ecto shows that hcab17 primarily interacts with the β-sandwich antigenic region. The interaction is mediated by five putative hydrogen bonds with two additional hydrogen bonds with the CD81 binding loop (Supplemental Table 3 and Figure 5 A-E). The β-sandwich surface is buried by CDRH1 and CDRH3 residues, accounting for 39% of the total Fab buried surface area, with no contribution from CDRH2 (Supplemental Table 3 and Figure 5D-E). As observed with the other structures in this study, the CDRLs do not make any contacts with E2, but three salt bridges between D56 of the hcab17 light chain and R543 of the E2 β-sandwich were observed (Supplemental Table 3 and Supplemental Figure 4D). Previously, we isolated a weakly neutralizing mAb HEPC46, which recognized the E2 central β-sandwich.26 The weak neutralizing activity of HEPC46 was likely explained by the proximal location of the HEPC46 epitope in the E2 β-sandwich, where HEPC46 is unlikely to prevent E2 from binding to the CD81 receptor. In addition to burying 691 Å2 of the β-sandwich, hcab17 also buries 231 Å2 of the CD81 binding loop distal to the receptor binding site and only weakly neutralizes 4 of 13 Tier 1–3 HCVpp with no neutralization of Tier 4 HCVpp (Supplemental Table 3 and Figure 3C). While both hcab17 and HEPC46 are weakly neutralizing antibodies, several bNAbs competed for binding with hcab17 and HEPC46, suggesting that β-sandwich antigenic region contains broadly neutralizing epitopes. Similar to some FLRY bNAbs including HEPC74, hcab55, and hcab64, hcab17 utilizes D2–15, which encodes a CDRH3 loop bearing a disulfide bridge that adopts a straight conformation. However, in hcab17 CDRH3 interacts with the β-sandwich and not the front layer.

Finally, the crystal structure of VH4–34 bNAb hcab40 in complex with E2ecto revealed an E2 neutralizing epitope in the back layer of E2 (Figure 5A–5E). Like mAbs that recognize the E2 β-sandwich, back layer-reactive mAbs are thought to be non-neutralizing.18,31,39 However, hcab40 neutralizes Tier 1–3 HCVpp (Figure 3C) and predominantly recognizing residues in the back layer of E2. Back layer residues bury 785 Å2 (66% of the total E2 BSA) in the hcab40-E2ecto structure (Figures 5D and 5E, Supplemental Table 3). In addition to several FRLY and AS412 residues that make direct contacts with CD81, two hcab40 back layer interface residues (P612 and Y613) were recently shown to be in close proximity (≤4Å) to tamarin CD81 in E2-CD81-LEL structure.40 While hcab40 CDRH1 and CDRH3 residues form several putative hydrogen bonds with residues in the back layer of E2, the S74 residue in the FR3 region of hcab40 also makes two hydrogen bonds with the E2 front layer (Supplemental Figure 4C). Notably, the two E2 FRLY residues contacted by hcab40, H445 and K446 (Supplemental Figure 4C), are also interface residues for FRLY bNAbs HEPC74, hcab55, and hcab64.

The hcab40 epitope in the back layer of E2 overlaps with the recently structurally characterized AR4A epitope in E1E241 (Supplemental Figure 5). The hcab40-E1E2 model indicates that hcab40 clashes with the E2 base region, indicating the potential flexibility of this region. Unlike E1E2-specific AR4A, hcab40 does not require E1 stabilization of E2 for binding, suggesting that the E2 back layer represents an additional target for E2-based immunogen design. The existence of neutralizing epitopes in the β-sandwich and back layer regions of E2 targeted by a non-VH1–69 bNAb suggests the possibility of a synergistic antibody response between FRLY-reactive, β-sandwich-reactive, and back layer-reactive bNAbs. Taken together, epitope mapping and structural analyses revealed that bNAbs use diverse VH and D-genes to target neutralizing epitopes in the front layer, β-sandwich, or back layer of E2. Structural analyses revealed conservation of approach angles and epitopes of FRLY bNAbs encoded by either VH1–46 or VH1–69 gene segments.

HCV bNAbs appear early in infection and display convergent evolution.

Given the similarity among binding epitopes of FRLY bNAbs utilizing diverse VH and D-genes, we hypothesized that these mAbs may have evolved convergently. We analyzed the bNAb sequences for shared residues arising in CDRH1–2 by somatic mutation (i.e. non-germline residues), and discovered the emergence of some of the same substitutions in multiple bNAbs regardless of V- or D-gene usage (Figure 6A). To determine whether each shared CDRH1–2 substitution was significantly enriched in FRLY bNAbs, we compared the proportion of FRLY bNAbs with a given substitution to the proportion of E2-nonreactive BCRs with that same substitution. E2-nonreactive BCRs included in this analysis were isolated from the same study subject and matched to the FRLY bNAbs by VH-gene usage and germline homology. Y29 and I30 (in CDRH1) and S54 (in CDRH2) substitutions were each significantly enriched in FRLY bNAbs (adjusted p=0.04, 0.005, 0.04 respectively; Figure 6A). Y29 arose in bNAbs utilizing VH1–46 or 1–69. Notably, Y29 formed a main-chain hydrogen bond with E2 residue T435 in the hcab64-E2 crystal structure (Supplemental Table 2) and was also an E2-interface residue in the HEPC74-E2 crystal structure.26 I30 arose in bNAbs utilizing VH1–46, 1–69, or 1–18, and formed a main chain hydrogen bond with E2 residue K446 in the hcab55-E2, hcab64-E2, and HEPC74-E2 crystal structures. S54 arose in bNAbs utilizing VH1–46, 1–69, or 1–18 and was an interface residue in the HEPC74-E2 crystal structure.

Figure 6. HCV FRLY bNAbs display convergent evolution.

(A) CDRH1–2 substitutions shared by multiple FRLY bNAbs and significantly enriched (bold) relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs from the same participant. E2-nonreactive BCRs were matched to FRLY bNAbs based on V-gene usage and % homology to germline sequences. CDRH3 amino acids shared by multiple FRLY bNAbs (A), β-sheet mAbs (B), or Back layer bNAbs (C) and significantly enriched (bold) relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs. E2-nonreactive BCRs were matched to FRLY, β-sheet, or back layer hcabs based on V-gene usage, % homology to germline, and CDRH3 length. Germline-encoded amino acids are in green, somatic mutation-encoded substitutions are in pink, and junctional nucleotide-encoded amino acids are in blue. P values were determined using Fischer’s exact test, adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Numbering according to the Kabat method. (D) Neutralizing breadth across a panel of 17 HCVpp by wild-type (WT) front-layer-reactive hcabs or hcabs with a single amino acid altered by site-directed mutagenesis. Each pair of linked points represents a single HCVpp. Values are the average of two independent experiments, tested in duplicate. For each mAb pair, HCVpp that were not neutralized by either WT or mutant mAbs were excluded from the analysis. Significance determined by Wilcoxon paired signed rank test. NS=not significant, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. (E) Neutralizing potency against heterologous HCVpp by wild type (WT) hcabs or hcabs with a single amino acid altered by site-directed mutagenesis. The HCVpp used for each test is indicated. Graphs are representative of two independent experiments performed in duplicate. Points are means and error bars represent standard deviations. See also Figure S6.

To identify significantly enriched amino acids within CDRH3 of FRLY bNAbs, we aligned FRLY bNAb CDRH3 sequences with sequences of E2-nonreactive CDRH3s from the same subject (matched based on CDRH3 lengths, VH gene usage, and germline homology). We identified 5 CDRH3 amino acids that were significantly enriched in FRLY bNAbs relative to E2-nonreactive B cells (Figure 6A). These residues were either germline encoded or encoded by somatic mutations or junctional insertions. Notably, an R100a residue, which arose by somatic mutation, was observed in CDRH3 93-fold more frequently than expected by chance, appearing in both VH1–46 and VH1–69-encoded bNAbs using D2–15 (p=0.0002). In the hcab55-E2 crystal structure, R100a formed two hydrogen bonds and a salt bridge with E531of E2 and was also an interface residue in the hcab64-E2 crystal structure (Supplemental Table 2). Taken together, this analysis showed that some somatic mutation-encoded amino acids were present in FRLY bNAbs significantly more than would be expected by chance, and some of these residues fell at the mAb interface with E2.

We performed the same amino acid enrichment analysis for non-FRLY hcabs falling in the β-sandwich (hcab7, hcab17, hcab22, hcab27, hcab35, hcab44) or back layer groups (hcab5, hcab22, hcab23, hcab31, hcab40). These hcabs used a variety of VH-genes, including 1–3, 1–18, 1–69, 3–20, 3–23, 4–30, and 4–34. For each of these hcab groups, we did not observe any significantly enriched substitutions in CDRH1–2. For the β-sandwich group, a G100g residue was significantly enriched in CDRH3 relative to E2-nonreactive BCRs (p=0.0005, Figure 6B). G100g was also an E2 contact residue in the hcab17-E2 crystal structure (Supplemental Table 3). For the back layer group, Y100f and G100k residues were significantly enriched (p=0.0001, 0.03, respectively, Figure 6C), but neither of these residues formed contacts with E2 in the hcab40-E2 crystal structure. Overall, these data indicate that genetically diverse bNAbs are capable of binding to the β-sandwich and back layer antigenic sites.

To confirm the functional significance of some of the enriched, shared FRLY bNAb residues, we selected a subset for mutagenesis analysis. We used site-directed mutagenesis to individually revert somatic mutation-encoded I30, or R100a substitutions in two bNAbs with two different V-genes to the germline-encoded amino acid (T/S, or S, respectively) (Figure 6D-E). We measured the relative neutralizing breadth of wild-type and mutant bNAbs across the panel of 17 HCVpp. Reversions in each mAb led to significantly reduced neutralizing activity across the HCVpp panel, except R100aS in hcab03, confirming that these substitutions were important for neutralizing breadth. Next, we tested neutralization of a single HCVpp by serial dilutions of each WT and mutant hcab pair (Figure 6E). Each reversion led to loss of neutralizing potency by both hcabs that were tested. Taken together, these site-directed mutagenesis experiments confirmed that residues in CDRH1 and 3 that were enriched and shared across diverse bNAbs enhanced the neutralizing breadth and potency of those bNAbs. This convergent evolution provides a mechanism to explain the capacity of bNAbs using multiple different VH-genes to target the front layer with very similar binding epitopes.

For some FRLY bNAbs, we were able to identify BCRs from the same B cell lineage in the longitudinal BCR-seq dataset obtained at days 279, 540, 1267, and 1842 post infection (Supplemental Figure 6), based upon matched VH and JH-gene usage and identical CDRH3 length. We used these longitudinal BCR lineage sequences to define the evolution of shared bNAb CDRH1–3 substitutions over time. Notably, I30 substitutions in CDRH1 appeared in hcab55/64 and HEPC74 lineages early in infection at D279 and were found in all BCR lineage sequences at every subsequent timepoint. Other bNAb-enriched amino acids, including R100a were also detected as early as D279 after infection and maintained in each lineage until D2178 when mAbs were isolated, although many substitutions were not present universally in all members of each bNAb lineage. For example, Y29 was detected in the hcab55/64 bNAb lineage at D279, D1267, D1842, and D2178, but was present in only 4 of 8 sequences in that lineage (Supplemental Figure 6). Overall, longitudinal BCR-seq analysis revealed that multiple FRLY bNAb B cell lineages were already detectable early after infection, and some substitutions that were shared across multiple bNAbs also arose early in infection and were then maintained for the entire ~1900 day sampling period. Early appearance and maintenance over time of these shared substitutions in a person who repeatedly cleared infection supports their importance for neutralizing breadth.

Discussion

In this study, we used a mixture of three soluble E2 ectodomain proteins to perform BCR-seq and culture of E2-reactive B cells from an elite neutralizer who spontaneously cleared multiple HCV infections. We isolated 55 E2-reactive mAbs, including 29 bNAbs, and characterized their neutralization breadth, epitope targets, and longitudinal evolution. We demonstrated that there is a preference but no necessity for VH1–69 or D2–2/D2–15 gene segment usage among HCV bNAbs, with the highest breadth bNAbs using a wide range of gene segments. These bNAbs targeted the conserved E2 front-layer (FRLY) as well as a variety of additional epitopes, including neutralizing epitopes in the β-sandwich and back layer of E2. Both β-sandwich and back layer-reactive mAbs were previously thought to be non-neutralizing.18,39 It remains to be determined which structural or biochemical features (bNAbs angle of approach, fine epitope signature, affinity) are responsible for the broad neutralization of HCV by β-sandwich or back layer-specific bNAbs. Nevertheless, the existence of multiple neutralizing epitopes suggests the possibility of a synergistic antibody response between bNAbs that target these sites. Additionally, through longitudinal BCR-seq analysis, we observed convergent evolution of multiple FRLY bNAb lineages, identifying a mechanism by which bNAbs can acquire neutralizing breadth regardless of their germline VH-gene usage. These findings highlight the plasticity of the HCV bNAb response and could guide vaccine development.

In a recent study by Weber et al.15, bNAbs primarily targeted the E2-front-layer and were almost exclusively reliant on the VH1–69 gene segment. We also found that utilization of VH1–69 strongly favored broad neutralizing activity, but in contrast with Weber et al., we isolated bNAbs utilizing a wide range of VH gene segments, targeting the front layer as well as a variety of other additional E2 epitopes. Numerous differences in experimental approach might explain these discrepancies. First, Weber et al. isolated bNAbs from individuals with chronic HCV infection, whereas our bNAbs were isolated from a person with an effective antibody response who spontaneously cleared multiple infections. Second, Weber et al. isolated E2-reactive B cells using a single-variant E2 protein fragment with deleted variable domains and mutated glycosylation sites. In contrast, we used a mixture of unmutated, full-length, antigenically diverse E2 ectodomain proteins.

These findings stand in contrast to studies of HIV-1 infection demonstrating that most bNAbs use a limited set of VH-genes, including VH1–69. In addition, many HIV bNAbs are extensively somatically mutated (~60% homology to germline) with unusual features like exceptionally long CDRH3s.21,22 This narrow genetic path to HIV bNAb induction has led to the use of complex, sequential vaccine strategies that have thus far failed to reliably induce bNAbs. We found that in addition to diverse VH and D-gene usage, HCV bNAbs are not extensively somatically mutated (>87% homology to germline), nor do they have exceptionally long CDRH3s (median <20 amino acids). Thus, the bNAb response against HCV resembles a more typical B cell response to pathogens like influenza or SARS-CoV-2 that should be inducible with already proven vaccine platforms and strategies.

Our findings are also useful for rational HCV vaccine antigen design. Convergent evolution points to a set of BCR amino acids that are of particular importance for neutralizing breadth. Through analysis of bNAb-E2 structures, we have identified the specific E2 residues that form contacts with these convergent bNAb positions. Stabilization or optimized presentation of these E2 residues could provide an avenue for enhancement of HCV vaccine antigens. In addition, since our data confirm that VH1–69 or D2–15 gene segments are not required for bNAb induction, animals that do not express orthologs of these gene segments, including mice, may be useful for preclinical evaluation of vaccine candidates.

Finally, it is not clear yet whether E2-based or E1E2-based immunogens would fulfill the requirements of an effective HCV vaccine.42,43 One theoretical advantage of E1E2 immunogens over E2 immunogens is the ability to elicit AR4A-like bNAbs that recognize the conformationally sensitive epitopes near the stem of E2, a region that is stabilized by interactions with E1. Unfortunately, purification of intact E1E2 heterodimers is difficult since the majority of transiently expressed E1E2 forms disulfide-crosslinked aggregates.44 In contrast, soluble E2 glycoproteins can be expressed at high levels in monomeric form. In the current study, we identified a cluster of potent bNAbs, including an extraordinarily broadly neutralizing antibody, designated hcab05, that binds to the back layer of E2. Structural analysis of a representative bNAb hcab40 from the back layer binding group indicated that its epitope overlaps with the AR4A epitope in E1E2 (Supplemental Figure 5). However, unlike AR4A, hcab40 and other hcabs that bind to the back layer of E2 do not require E1 stabilization of E2 for binding, suggesting that E2 immunogens might be able to elicit bNAbs that bind to AR4A/hcab40 overlapping epitopes. Additional studies are needed to determine whether immunization with E2 can elicit back layer-specific bNAbs that compete for binding with AR4A-like bNAbs.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that targeting of a wide variety of E2 epitopes and convergent evolution of antibodies targeting the E2 front layer allows genetically diverse human antibodies to acquire a broadly neutralizing phenotype. Structural studies of these bNAbs in complex with E2 define conserved bNAb-E2 interactions, identifying residues in E2 that could be stabilized or optimally exposed in rationally-designed vaccine antigens. Together, these findings support the feasibility of an HCV vaccine, and support development of vaccines that can induce bNAbs targeting multiple E2 epitopes.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that the comprehensive BCR repertoire analysis was performed in only one EN. We demonstrated that the plasma bNAb response in this individual was representative of responses in other ENs, indicating that the findings may be generalizable across individuals with broadly neutralizing plasma. However, it is not possible to conclude that genetically diverse bNAbs targeting varied epitopes, in contrast with the VH1–69, FRLY-focused bNAbs previously reported in chronically-infected persons32, are the explanation for clearance or persistence of HCV infection. We also cannot draw any conclusions about the role of sex or other demographic data in the antibody responses observed. Similar bNAb analyses should be performed in additional EN and chronically-infected individuals to shed further light on this important question.

STAR Methods

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact.

Materials availability

E2 ectodomains and antibodies will be made available by the lead contact upon request with a Material Transfer Agreement for non-commercial usage.

Data and code availability

Coordinates for atomic models are deposited in the Protein Data Bank and are publicly available from the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

Raw BCR-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive and are available from the date of publication. The accession number is listed in the key resources table.

The R code used to analyze the data as well as scripts for CDR3 alignment can be found in a Zenodo repository, with the DOI available in the key resources table.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-CD81 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555675, RRID: AB_396028 |

| BD Pharmingen™ HRP Anti-Human IgG | BD Biosciences | Cat# 555788, Clone G18–145, RRID: AB_396123 |

| BD Horizon™ BB515 Mouse Anti-Human IgM | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564622, Clone G20–127, RRID: AB_2738869 |

| BD Horizon™ BB515 Mouse Anti-Human IgD | BD Biosciences | Cat# 565243, Clone IA6–2, RRID: AB_2744485 |

| BD Horizon™ APC-R700 Mouse Anti-Human CD19 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564977, Clone HIB19, RRID: AB_2744308 |

| BD Horizon™ BV421 Mouse Anti-Human CD19 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562440, Clone HIB19, RRID: AB_11153299 |

| BD Pharmingen™ APC-H7 Mouse Anti-Human CD3 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 560176, Clone SK7, RRID: AB_1645475 |

| BD Pharmingen™ PE Mouse Anti-Human CD10 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 561002, Clone HI10a, RRID: AB_395776 |

| BD Horizon™ BV421 Mouse IgG1, k Isotype Control | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562438, Clone X40, RRID: AB_11207319 |

| BD Pharmingen™ PE Mouse IgG2a, κ Isotype Control | BD Biosciences | Cat# 554648, Clone G155–178, RRID: AB_395491 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase AffiniPure™ Goat Anti-Human IgG, Fcγ fragment specific | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 109–055-098, RRID: AB_2337608 |

| Goat anti Human IgG Fab Secondary Antibody | MyBioSource | Cat# MBS571434 |

| IgG from human serum | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# I4506, RRID: AB_1163606 |

| 6x-His Tag Monoclonal Antibody (HIS.H8) | ThermoFisher | Cat# MA1–21315, Clone HIS.H8, RRID: AB_557403 |

| HEPC74 | Bailey et al.(17) | N/A |

| HEPC46 | Flyak et al.(26) | N/A |

| HEPC108 | Colbert et al.(34) | N/A |

| HC-1 | Keck et al.(35) | N/A |

| HC84.26 | Keck et al.(36) | N/A |

| AR3A | Law et al.(16) | N/A |

| AR3C | Law et al.(16) | N/A |

| AR4A | de la Peña et al.(41) | N/A |

| AR1B | Law et al.(16) | N/A |

| HCV1 | Broering et al.(37) | N/A |

| Monoclonal anti-HCV patient-derived hcab antibodies | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| R&D Systems™ Recombinant Human IL-2 Protein | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 202IL050, Gene 3558, Accession P60568 |

| R&D Systems™ Recombinant Human IL-21 Protein | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 8879IL050, Gene 59067, Accession Q9HBE4 |

| BD™ CompBeads Anti-Rat and Anti-Hamster Ig κ /Negative Control Compensation Particles Set | BD Biosciences | Cat# 552845, Clone RG7/7.6, RRID: AB_10058522 |

| BD™ CompBeads Anti-Mouse Ig, κ/Negative Control Compensation Particles Set | BD Biosciences | Cat# 552843, RRID: AB_10051478 |

| BD Pharmingen™ Human BD Fc Block™ | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564220, Clone Fc1, RRID: AB_2728082 |

| BD Pharmingen™ Propidium Iodide Staining Solution | BD Biosciences | Cat# 556463 |

| ArC™ Amine Reactive Compensation Bead Kit | ThermoFisher | Cat# A10346 |

| Lipofectamine™ 2000 Transfection Reagent | ThermoFisher | Cat# 11668019 |

| 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine Liquid Substrate | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# T4319 |

| Kifunensine | Sigma Aldrich | Cat# K1140 |

| Pure Galanthus nivalis lectin (Snowdrop Bulb) | EY Labs | Cat# L74015 |

| PEGRx HT | Hampton Research | Cat# HR2–086 |

| PEG/Ion HT | Hampton Research | Cat# HR2–139 |

| JCSG-plus HT-96 | Molecular Dimensions | Cat# MD1–40 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Library Efficiency™ DH5α Competent Cells | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 18263012 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human plasma | Cox et al.(47) | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Ortho HCV version 3.0 ELISA Test System | Ortho Clinical Diagnostics | Cat# 930740 |

| In-Fusion HD Cloning Plus | Clontech | Cat# 638909 |

| HCV Real-time Assay | Abbot | Cat# 01N30–090 |

| QIAamp viral RNA mini column | Qiagen | Cat# 52904 |

| Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat# E1500 |

| QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent | Cat# 210513 |

| EZ-link® Micro NHS-PEG4-Biotinylation Kit | Thermo Scientific | Cat# 21955 |

| Octet® Streptavidin (SA) Biosensor | Sartorius | Cat# 18–5019 |

| Deposited data | ||

| hcab55-E2ecto | This paper | PDB: 8W0V |

| hcab64-E2ecto | This paper | PDB: 8W0W |

| hcab40-E2ecto | This paper | PDB: 8W0X |

| hcab17-E2ecto | This paper | PDB: 8W0Y |

| BCR-seq | This paper | NCBI sequence read archive: PRJNA921709 |

| R code for BCR analysis | This paper | http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10680494 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human: Huh7 | Nakabayashi et al.(48) | RRID: CVCL_0336 |

| Human: CD81-knockout HEK293T | Kalemera et al.(49) | N/A |

| Human: HEK293T/17 | ATCC | Cat# CRL-11268, RRID: CVCL_1926 |

| Human: Hep3B2.1–7 | ATCC | Cat# HB-8064, RRID: CVCL_0326 |

| Human: Expi293F™ Cells | ThermoFisher | Cat# A14527 |

| Mouse: Fibroblast 3T3-msCD40L Cells, ARP-12535 | BEI resources, Huang et al.(50) | Cat# ARP-12535 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Random Hexamer Primer | ThermoFisher | Cat# SO142 |

| B cell gene PCR Primers | Designed from Tiller et al.(52) | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Human antibody expression vector IgG1 (heavy and light) | pTWIST | N/A |

| pTT5 mammalian Fab expression vector | National Research Council of Canada | N/A |

| pNL4–3.Luc.R-E | NIH AIDS Reagent | Cat# 3418 |

| pAdvantage | Promega | Cat# E1711 |

| HCV E1E2 plasmids for HCVpp | Salas et al.(29) | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Adobe Illustrator CC 2018 | Adobe Inc. | N/A |

| FlowJo™ Software 10.5.3 | Becton, Dickinson and Company | N/A |

| Geneious R10 and Geneious Prime | Geneious | RRID: SCR_010519 |

| Prism 7 | GraphPad | RRID: SCR_002798 |

| The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System v2.0 | Schrödinger, LLC | RRID: SCR_000305 |

| Phenix | Adams et al.(59) | RRID: SCR_014224 |

| Coot | Emsley and Cowtan et al.(60) | RRID: SCR_014222 |

| PDBePISA | Krissinel and Henrick et al.(62) | N/A |

| Other | ||

| BD FACSAria™ Fusion Flow Cytometer | BD Biosciences | N/A |

| DMI3000 B Manual Inverted Microscope for Basic Life Science Research | Leica | N/A |

| Pierce High Sensitivity Streptavidin-HRP | ThermoFisher | Cat# 21130 |

| Thermo Scientific™ Clear Flat-Bottom Immuno Nonsterile 96-Well Plates | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 12–565-136 |

| Thermo Scientific™ Clear Flat-Bottom Immuno Nonsterile 96-Well Plates | Fisher Scientific | Cat# 14–245-61 |

| Superdex 200 Increase small-scale SEC columns | Cytiva | Cat# 28990944 |

| HisTrap HP His tag protein purification columns | Cytiva | Cat# 17524802 |

| HCV 1b09 strain E1E2 sequence | GenBank | Accession KJ187984.1 |

Experimental models and participant details

Human participants

Baltimore Before and After Acute Study of Hepatitis (BBAASH) is a prospective cohort 5,28,45–47 of people who inject drugs in Baltimore who are followed from before the time they are infected with HCV, through spontaneous clearance and/or persistence of HCV. Participants in the BBAASH cohort are adults enrolled in Baltimore, MD.28 These identity-unlinked samples are stored under code in aliquots in −80 freezers (plasma) or liquid nitrogen (PBMC) with continuous temperature monitoring. Participant C110 is male and Caucasian. Age and other demographic information were not essential for this study so were not released. HCV viral loads (IU/mL) were quantified after RNA extraction using Abbot real-time HCV PCR. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins Hospital and informed written consent was obtained from all study participants.

Cell lines

Huh748 cell line (male) was obtained from Dr. Charles Rice, Rockefeller University, New York, USA. HEK-293T-CD81 knockout cells49 (female) were obtained from Dr. Joe Grove, University of Glasgow, United Kingdom. HEK293-T cell line (female) was obtained from ATCC, and Expi293F (female) from ThermoFisher. 3T3-msCD40L cells50 (male) were obtained from the NIH AIDS reagent bank. Cells were grown under standard aseptic conditions at 37°C and authenticated based on expected microscopic morphology and phenotype (e.g. expected infection with HCVpp (Huh7) or high transfection efficiency and protein production (HEK-293T-CD81 knockout cells, HEK293-T, and Expi293F).

Method Details

Soluble E2 variants used for B cell staining

Genes encoding 1a157, 1b09, and 1b21 E2 ectodomains, residues 384–643 (numbering based on strain H77), were cloned into a mammalian expression vector pHCMV3 that includes an N-terminal Ig-kappa secretion signal and expressed by transient transfection of HEK293T cells. As previously described30, these 3 full length, unmutated E2 ectodomains were selected from a library of 89 distinct genotype 1 HCV E1E2 variants.51

Cell staining and flow cytometry

As previously described30, PBMCs were stained with a mixture of the 3 E2 proteins. Briefly, following incubation and blocking by anti-CD81 antibody (BD Cat #555675) and Fc blocker (BD Cat #564220) in FACS Buffer (1x PBS with 1% BSA), the PBMCs were coated with the E2 mixture at 5 μg/mL. Next, the PBMCs were incubated with propidium iodide (PI), CD10-PE, CD19-BV421, CD3-APC H7, IgM-BB515, IgD-BB515, and Anti His-AF647 before sorting E2-reactive class-switched memory B cells using a MoFlo flow cytometer (BD).

Sorted E2-reactive B cell cultures and ELISAs

Following previous methods30,50, sorted memory B cells were seeded at 1, 2, 4, and 20 B cells per well in clear u-bottom 96-well cell culture plates along with irradiated mouse 3T3 fibroblast cells expressing CD40L, IL-2 (Fisher Scientific Cat #202IL050CF), and IL-21 (Fisher Scientific Cat #8879IL050). 3T3-CD40L cells were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Cat #12535 3T3-msCD40L cells, from Dr. Mark Connors. On day 14, supernatants were isolated from the cultures, and cells were stored in −80 with lysis buffer.

For IgG ELISAs, we followed a protocol that was shared by Dr. Steven Foung’s laboratory at Stanford University School of Medicine. Briefly, 96-well Maxisorp plates were coated with Jackson Alkaline Phosphatase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Human IgG, Fcγ fragment specific (Fisher Scientific Cat #109–055-098). Following incubation with culture supernatants, Goat Anti-Human IgG Fab Secondary Antibody (MyBioSource Cat #MBS8216436) was used at a dilution of 1:4,000, with alkaline phosphatase yellow (pNPP) for readout.

For E2 antigen-specific ELISAs, Immulon 2b microtiter plates were coated with Lectin followed by incubation with E2 antigen overnight. Plates were blocked with PBS-TMG (PBS + 0.5% tween 20+ 1% non-fat dry milk+1% goat serum) and then incubated with B cell culture supernatants or mAbs. Anti-human IgG-HRP (BD-Pharmingen Cat #555788) was used at a 1:4,000 dilution and TMB peroxidase substrate to develop with 1N sulfuric acid used to stop the reaction.

Monoclonal antibody expression

RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) by the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was reverse transcribed by random hexamers using SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher) by the manufacturer’s instructions. Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (ThermoFisher) was used to perform heavy and light chain nested PCR reactions in 96-well plates containing 20nm each primer or primer mix as described by Tiller et al.52 PCR products were agarose gel purified and sanger sequenced.

Sequences were synthesized (Twist Biosciences) and cloned into a human IgG1, IgK, or IgL expression plasmids (pTwist CMV BetaGlobin WPRE Neo_IgG1Fc, pTwist CMV BetaGlobin WPRE Neo_Kappa_TAG or pTwist CMV BetaGlobin WPRE Neo_Lambda_TAG). Expi293 cells were transfected with the heavy and light chain plasmids using the Gibco Expi293 Expression System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Monoclonal immunoglobulin proteins were harvested and purified using Pierce™ Protein G Agarose (Cat. #20398) and concentrated using Pierce™ Protein Concentrator PES, 30K MWCO (Cat. #88529).

B cell receptor sequencing

Sorted cells were lysed and RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) as described above. Briefly, cells in lysis buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol were combined with 70% ethanol and applied to a purification column. Following multiple washes and the application of DNAse, RNA was eluted in RNAse free water. RNA quality was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). cDNA libraries were produced using the SMARTer Human BCR IgG IgM H/K/L Profiling Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and with the addition of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). AMPure XP beads (Beckman) were used for purification steps. All sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq at a depth of 1 million reads. cDNA library quality was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and quantified using a Qubit (ThermoFisher). Clonotypes were quantified using Cogent NGS Immune Profiler Software (Takara). All additional analysis was done in R.

HCVpp and neutralization assays

As described53, HIV group-specific antigen (Gag)-packaged HCVpps were produced by lipofectamine-mediated transfection of HCV E1/E2 expression plasmid, pNL4–3.Luc.R-E-expression plasmid containing the env-defective HIV proviral genome (National Institutes of Health AIDS Reagent Program), and pAdVantage (Promega, Madison, WI) plasmid into CD81-knockout HEK293T cells.49 The panel of 15 HCVpp as described by Salas et al.29 plus an additional 2 Tier 4 resistant variants HCVpp (UKNP2.4.1 and UKNP6.1.1) were used in neutralization assays. Neutralization assays were performed as previously described.53,54 Briefly, purified mAbs at 100μg/mL or heat-inactivated plasma samples at 1:100 dilution were incubated with HCVpp for 1 hour at 37°C prior to addition to HuH7 cells in duplicate with nonspecific human isotype control. The percentage of neutralization was calculated as [1 − (RLUmAb/RLUhIgG)] × 100, with the values averaged across 2 biological and 2 technical replicates. Based on 65 independent tests performed in duplicate with a variety of different HCVpp29, nonspecific neutralization by isotype control mAb R04 at 100mcg/mL was an average of 1.0%, with a standard deviation of 19.9%. Therefore, we set the cutoff for true-positive neutralization at >25%.

ELISA assays for epitope mapping

To determine E2 front layer (FRLY) or antigen site 412 (AS412) dependent binding, ELISA binding of each mAb was measured with wild-type 1a157 E2, 1a157 E2 FRLY KO or 1a157 E2 AS412 KO proteins. 1a157 E2 FRLY KO contains mutations T425A, L427A, N428A, S432A, G436A, W437A, G530A, and D535A that abrogate binding of known FRLY-reactive mAbs. 1a53 E2 AS412 KO contains mutations L413A, G418A, and W420A that abrogate binding of known AS412-reactive mAbs.

For all ELISAs, Immulon 2b microtiter plates were coated with GNA-lectin followed by coating with either 1a157, 1a157 FRLY KO, 1a53, 1a53 AS412 KO, H77, or H77 alanine mutant proteins. Purified hcab mAbs were tested at 10ug/ml and those with higher affinity were titrated and then tested at ~their EC90 concentration (HEPC74, hcab27, hcab31, hcab48, and hcab60). Binding OD450 was normalized for relative protein concentration of each sE2 protein using OD450 of anti-HIS binding for each variant. mAbs were separated based on front layer affinity and then hierarchical clustering using Ward’s minimum variance method in the hclust R package was used. An unrooted clustering tree was created with the ape R library, as previously described.55

Bio-Layer Interferometry epitope binning experiments.

Competition-binding studies using biolayer interferometry and biotinylated HCV E2 (EZ-link® Micro NHS-PEG4-Biotinylation Kit, Thermo Scientific #21955) (2–4 μg/mL) were performed on an Octet RH16 Biolayer Interferometer (Sartorius), as described previously.56 In brief, the biotinylated E2 was immobilized onto streptavidin-coated biosensor tips. After a brief washing step, biosensor tips were immersed first into the wells containing primary antibody at a concentration of 50 μg/mL and then into the wells containing competing mAbs at a concentration of 50 μg/mL. The percent binding of the competing mAb in the presence of the first mAb was determined by comparing the maximal signal of competing mAb applied after the first mAb complex to the maximal signal of competing mAb alone.

Expression and purification of E2-Fab Complexes

hcab55 Fab-1b09 E2ecto, hcab64 Fab-1b09 E2ecto, and hcab40 Fab-1b09 E2ecto complexes for structural studies were expressed by co-transfecting expression vectors encoding His-tagged Fab and untagged E2 and purifying Fab-E2 complexes from supernatants using Ni-NTA chromatography on HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) followed by SEC on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). Expi293F cells were grown in the presence of 5 mM kifunensine (Sigma) to express the hcab Fab-E2ecto complexes.

Crystallization

Commercially-available screens from Hampton Research and Molecular Dimensions were used to screen initial crystallization conditions by vapor diffusion in sitting drops. hcab55-E2ecto crystals were grown using 0.2 μL of the protein complex in TBS and 0.2 μL of mother liquor (0.2 M lithium citrate tribasic tetrahydrate and 20% PEG 3,350) and cryoprotected in mother liquor supplemented with 25% (v/v) glycerol. hcab64-E2ecto crystals were grown using 0.2 μL of the protein complex in TBS and 0.2 μL of mother liquor (8% Tacsimate, pH 7.0 and 20% PEG 3,350) and cryoprotected in mother liquor supplemented with 25% (v/v) glycerol. Hcab17-E2ecto crystals were grown using 0.2 μL of the protein complex in TBS and 0.2 μL of mother liquor (1.0 M Sodium citrate tribasic dihydrate and 0.1 M Sodium cacodylate pH 6.5) and cryoprotected in mother liquor supplemented with 25% (v/v) glycerol. hcab40-E2ecto crystals were grown using 0.2 μL of the protein complex in TBS and 0.2 μL of mother liquor (0.1 M Sodium malonate pH 6.0 and 12% PEG 3,350) and cryoprotected in mother liquor supplemented with 30% (v/v) glycerol.

X-ray diffraction data from cryopreserved crystals were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource on beamline 12–2 using a PILATUS 6M detector. Images were processed and scaled using iMosflm57 and Aimless as implemented in the CCP4 software suite.58 Structures were solved by molecular replacement using the HEPC74-Fab (PDB 6MEH) and 1b09 HCV E2ecto (PDB 6MEI) structures as search models. The models were refined and validated using Phenix.refine.59 Iterative manual model building and corrections were performed using Coot.60 Glycans were initially interpreted and modeled using Fo – Fc maps calculated with model phases contoured at 2s, followed by 2Fo – Fc simulated annealing composite omit maps generated in Phenix in which modeled glycans were omitted to remove model bias.59 The quality of the final models was examined using MolProbity (Supplemental Table 1).61

Models were superimposed and figures rendered using the PyMOL molecular visualization system (Version 2.1, Schrödinger, LLC). Buried surface areas (BSAs) were determined using the PDBePISA web-based interactive tool.62 Potential hydrogen bonds were assigned using criteria of a distance of <4.0 Å and an A-D-H angle of >90°, and the maximum distance allowed for a van der Waals interaction was 4.0 Å. Rmsd calculations were done in PyMOL following pairwise Cα alignments without excluding outliers. Antibody residues were numbered according to the Kabat numbering scheme, and ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) definitions of CDRs were used throughout the paper,

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Cogent NGS Immune Profiler Software (Takara) was used for initial sequence processing. Further analysis was completed in R studio version 2023.06.1+524 (running R version 4.3.1) and Prism (Graphpad). Statistical tests used to calculate significance are noted in the legend of each figure.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Isolated longitudinal samples from a person with spontaneous HCV clearance who expressed potent bNAbs.

These HCV bNAbs were encoded by a variety of VH and D-genes.

HCV bNAbs targeted at least three distinct antigenic sites on the HCV E2 protein.

E2 front-layer-reactive bNAbs evolved convergently to acquire neutralizing breadth.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in the BBAASH cohort and members of the Johns Hopkins Viral Hepatitis Center for thoughtful discussion. We thank the Bloomberg Flow Cytometry and Immunology Core for equipment and technical assistance, and Hao Zhang. M.D. for the acquisition of sorted cells. We thank Mansun Law for providing single alanine E1E2 mutant expression plasmids. Bio-Layer Interferometry epitope binning data was acquired through the Cornell Institute of Biotechnology's Imaging Facility, with NIH S10OD032273-01 funding for the shared Octet RH16 Biolayer Interferometer. This research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) (NIH grant U19 AI159822 to J.R.B and A.I.F) (NIH grant R01AI127469 to J.R.B. and P.J.B.) and (NIH grants K99 AI153465 and R00 AI153465 to A.I.F.) (content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH) and the Molecular Observatory at Caltech supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (contract no DE-AC02-76SF00515). The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by NIHGMS (P41GM103393).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

JRB and COO have filed a provisional patent 63/470,326 related to monoclonal antibodies described in this manuscript.

References

- 1.van der Meer AJ, Veldt BJ, Feld JJ, Wedemeyer H, Dufour JF, Lammert F, Duarte-Rojo A, Heathcote EJ, Manns MP, Kuske L, et al. (2012). Association between sustained virological response and all-cause mortality among patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced hepatic fibrosis. JAMA 308, 2584–2593. 1487498 [pii]; 10.1001/jama.2012.144878 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis GL, Alter MJ, El-Serag H, Poynard T, and Jennings LW (2010). Aging of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected persons in the United States: a multiple cohort model of HCV prevalence and disease progression. Gastroenterology 138, 513–521. S0016-5085(09)01885-X [pii]; 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.067 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prevention, C.f.D.C.a. (2018). Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report 2018 — Hepatitis C. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suryaprasad AG, White JZ, Xu F, Eichler BA, Hamilton J, Patel A, Hamdounia SB, Church DR, Barton K, Fisher C, et al. (2014). Emerging Epidemic of Hepatitis C Virus Infections Among Young Non-Urban Persons who Inject Drugs in the United States, 2006–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis 10.1093/cid/ciu643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osburn WO, Fisher BE, Dowd KA, Urban G, Liu L, Ray SC, Thomas DL, and Cox AL (2010). Spontaneous Control of Primary Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Immunity Against Persistent Reinfection. Gastroenterology 138, 315–324. S0016-5085(09)01658-8 [pii]; 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.017 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D, O'Huigin C, Kidd J, Kidd K, Khakoo SI, Alexander G, et al. (2009). Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature 461, 798–801. 10.1038/nature08463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osburn WO, Snider AE, Wells BL, Latanich R, Bailey JR, Thomas DL, Cox AL, and Ray SC (2014). Clearance of hepatitis C infection is associated with the early appearance of broad neutralizing antibody responses. Hepatology 59, 2140–2151. 10.1002/hep.27013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pestka JM, Zeisel MB, Blaser E, Schurmann P, Bartosch B, Cosset FL, Patel AH, Meisel H, Baumert J, Viazov S, et al. (2007). Rapid induction of virus-neutralizing antibodies and viral clearance in a single-source outbreak of hepatitis C. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A 104, 6025–6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raghuraman S, Park H, Osburn WO, Winkelstein E, Edlin BR, and Rehermann B (2012). Spontaneous clearance of chronic hepatitis C virus infection is associated with appearance of neutralizing antibodies and reversal of T-cell exhaustion. J.Infect.Dis 205, 763–771. jir835 [pii]; 10.1093/infdis/jir835 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinchen VJ, Zahid MN, Flyak AI, Soliman MG, Learn GH, Wang S, Davidson E, Doranz BJ, Ray SC, Cox AL, et al. (2018). Broadly Neutralizing Antibody Mediated Clearance of Human Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Cell Host Microbe 24, 717–730 e715. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Houghton M (2011). Prospects for prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines against the hepatitis C viruses. Immunol. Rev 239, 99–108. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang TJ (2013). Current progress in development of hepatitis C virus vaccines. Nat. Med 19, 869–878. 10.1038/nm.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frey SE, Houghton M, Coates S, Abrignani S, Chien D, Rosa D, Pileri P, Ray R, Di Bisceglie AM, Rinella P, et al. (2010). Safety and immunogenicity of HCV E1E2 vaccine adjuvanted with MF59 administered to healthy adults. Vaccine 28, 6367–6373. S0264-410X(10)00925-4 [pii]; 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.06.084 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jong YP, Dorner M, Mommersteeg MC, Xiao JW, Balazs AB, Robbins JB, Winer BY, Gerges S, Vega K, Labitt RN, et al. (2014). Broadly neutralizing antibodies abrogate established hepatitis C virus infection. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 254ra129. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber T, Potthoff J, Bizu S, Labuhn M, Dold L, Schoofs T, Horning M, Ercanoglu MS, Kreer C, Gieselmann L, et al. (2022). Analysis of antibodies from HCV elite neutralizers identifies genetic determinants of broad neutralization. Immunity. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Law M, Maruyama T, Lewis J, Giang E, Tarr AW, Stamataki Z, Gastaminza P, Chisari FV, Jones IM, Fox RI, et al. (2008). Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nat. Med 14, 25–27. 10.1038/nm1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey JR, Flyak AI, Cohen VJ, Li H, Wasilewski LN, Snider AE, Wang S, Learn GH, Kose N, Loerinc L, et al. (2017). Broadly neutralizing antibodies with few somatic mutations and hepatitis C virus clearance. JCI Insight 2. 10.1172/jci.insight.92872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadlock KG, Lanford RE, Perkins S, Rowe J, Yang Q, Levy S, Pileri P, Abrignani S, and Foung SK (2000). Human monoclonal antibodies that inhibit binding of hepatitis C virus E2 protein to CD81 and recognize conserved conformational epitopes. J.Virol 74, 10407–10416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan CH, Hadlock KG, Foung SK, and Levy S (2001). V(H)1–69 gene is preferentially used by hepatitis C virus-associated B cell lymphomas and by normal B cells responding to the E2 viral antigen. Blood 97, 1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tzarum N, Giang E, Kong L, He L, Prentoe J, Augestad E, Hua Y, Castillo S, Lauer GM, Bukh J, et al. (2019). Genetic and structural insights into broad neutralization of hepatitis C virus by human VH1–69 antibodies. Sci Adv 5, eaav1882. 10.1126/sciadv.aav1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen F, Tzarum N, Wilson IA, and Law M (2019). VH1–69 antiviral broadly neutralizing antibodies: genetics, structures, and relevance to rational vaccine design. Curr. Opin. Virol. 34, 149–159. 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S, Ju B, Shapero B, Lin X, Ren L, Zhang L, Li D, Zhou Z, Feng Y, Sou C, et al. (2020). A VH1–69 antibody lineage from an infected Chinese donor potently neutralizes HIV-1 by targeting the V3 glycan supersite. Science Advances 6, eabb1328. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang S, Xie J, Zhu X, Wu NC, Lerner RA, and Wilson IA (2017). Antibody 27F3 Broadly Targets Influenza A Group 1 and 2 Hemagglutinins through a Further Variation in VH1–69 Antibody Orientation on the HA Stem. Cell Reports 20, 2935–2943. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lingwood D, McTamney PM, Yassine HM, Whittle JR, Guo X, Boyington JC, Wei CJ, and Nabel GJ (2012). Structural and genetic basis for development of broadly neutralizing influenza antibodies. Nature 489, 566–570. 10.1038/nature11371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SA, Burton SL, Kilembe W, Lakhi S, Karita E, Price M, Allen S, and Derdeyn CA (2019). VH1–69 Utilizing Antibodies Are Capable of Mediating Non-neutralizing Fc-Mediated Effector Functions Against the Transmitted/Founder gp120. Front. Immunol 9. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]