Abstract

Objective

To improve the accuracy and completeness of reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy, to allow readers to assess the potential for bias in a study, and to evaluate a study's generalisability.

Methods

The Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) steering committee searched the literature to identify publications on the appropriate conduct and reporting of diagnostic studies and extracted potential items into an extensive list. Researchers, editors, and members of professional organisations shortened this list during a two day consensus meeting, with the goal of developing a checklist and a generic flow diagram for studies of diagnostic accuracy.

Results

The search for published guidelines about diagnostic research yielded 33 previously published checklists, from which we extracted a list of 75 potential items. At the consensus meeting, participants shortened the list to a 25 item checklist, by using evidence, whenever available. A prototype of a flow diagram provides information about the method of patient recruitment, the order of test execution, and the numbers of patients undergoing the test under evaluation and the reference standard, or both.

Conclusions

Evaluation of research depends on complete and accurate reporting. If medical journals adopt the STARD checklist and flow diagram, the quality of reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy should improve to the advantage of clinicians, researchers, reviewers, journals, and the public.

The Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) steering group aims to improve the accuracy and completeness of reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy. The group describes and explains the development of a checklist and flow diagram for authors of reports

Introduction

The world of diagnostic tests is highly dynamic. New tests are developed at a fast rate, and the technology of existing tests is continuously being improved. Exaggerated and biased results from poorly designed and reported diagnostic studies can trigger their premature dissemination and lead physicians into making incorrect treatment decisions. A rigorous evaluation of diagnostic tests before introduction into clinical practice could not only reduce the number of unwanted clinical consequences related to misleading estimates of test accuracy but also limit healthcare costs by preventing unnecessary testing. Studies to determine the diagnostic accuracy of a test are a vital part of this evaluation process.1–3

In studies of diagnostic accuracy, the outcomes from one or more tests under evaluation are compared with outcomes from the reference standard—both measured in subjects who are suspected of having the condition of interest. The term test refers to any method for obtaining additional information on a patient's health status. It includes information from history and physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging tests, function tests, and histopathology. The condition of interest or target condition can refer to a particular disease or to any other identifiable condition that may prompt clinical actions, such as further diagnostic testing, or the initiation, modification, or termination of treatment. In this framework, the reference standard is considered to be the best available method for establishing the presence or absence of the condition of interest. The reference standard can be a single method, or a combination of methods, to establish the presence of the target condition. It can include laboratory tests, imaging tests, and pathology, as well as dedicated clinical follow up of subjects. The term accuracy refers to the amount of agreement between the information from the test under evaluation, referred to as the index test, and the reference standard. Diagnostic accuracy can be expressed in many ways, including sensitivity and specificity, likelihood ratios, diagnostic odds ratio, and the area under a receiver-operator characteristic curve.4–6

Several potential threats to the internal and external validity of a study on diagnostic accuracy exist. A survey of studies of diagnostic accuracy published in four major medical journals between 1978 and 1993 revealed that the quality of methods was mediocre at best.7 However, evaluations were hampered because many reports lacked information on key elements of design, conduct, and analysis of diagnostic studies.7 The absence of critical information about the design and conduct of diagnostic studies has been confirmed by authors of meta-analyses.8,9 As in any other type of research, flaws in study design can lead to biased results. One report showed that diagnostic studies with specific design features are associated with biased, optimistic estimates of diagnostic accuracy compared with studies without such features.10

At the 1999 Cochrane colloquium meeting in Rome, the Cochrane diagnostic and screening test methods working group discussed the low methodological quality and substandard reporting of diagnostic test evaluations. The working group felt that the first step towards correcting these problems was to improve the quality of reporting of diagnostic studies. Following the successful CONSORT initiative,11–13 the working group aimed to develop a checklist of items that should be included in the report of a study on diagnostic accuracy.

The objective of the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) initiative is to improve the quality of reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy. Complete and accurate reporting allows readers to detect the potential for bias in a study (internal validity) and to assess the generalisability and applicability of results (external validity).

Methods

The STARD steering committee (see bmj.com) started with an extensive search to identify publications on the conduct and reporting of diagnostic studies. This search included Medline, Embase, BIOSIS, and the methodological database from the Cochrane Collaboration up to July 2000. In addition, the members of the steering committee examined reference lists of retrieved articles, searched personal files, and contacted other experts in the field of diagnostic research. They reviewed all relevant publications and extracted an extended list of potential checklist items.

Subsequently, the STARD steering committee convened a two day consensus meeting for invited experts from the following interest groups: researchers, editors, methodologists, and professional organisations. The aim of the conference was to reduce the extended list of potential items, where appropriate, and to discuss the optimal format and phrasing of the checklist. The selection of items to retain was based on evidence whenever possible.

The meeting format consisted of a mixture of small group sessions and plenary sessions. Each small group focused on a group of related items in the list. The suggestions of the small groups then were discussed in plenary sessions. Overnight, a first draft of the STARD checklist was assembled on the basis of suggestions from the small group and additional remarks from the plenary sessions. All meeting attendees discussed this version the next day and made additional changes. The members of the STARD group could suggest further changes through a later round of comments by email.

Potential users field tested the conference version of the checklist and flow diagram, and additional comments were collected. This version was placed on the CONSORT website, with a call for comments. The STARD steering committee discussed all comments and assembled the final checklist.

Results

The search for published guidelines for diagnostic research yielded 33 lists. Based on these published guidelines and on input of steering and STARD group members, the steering committee assembled a list of 75 items. During the consensus meeting on 16–17 September 2000, participants consolidated and eliminated items to form the 25 item checklist. Conference members made major revisions to the phrasing and format of the checklist.

The STARD group received valuable comments and remarks during the various stages of evaluation after the conference, which resulted in the version of the STARD checklist in the table.

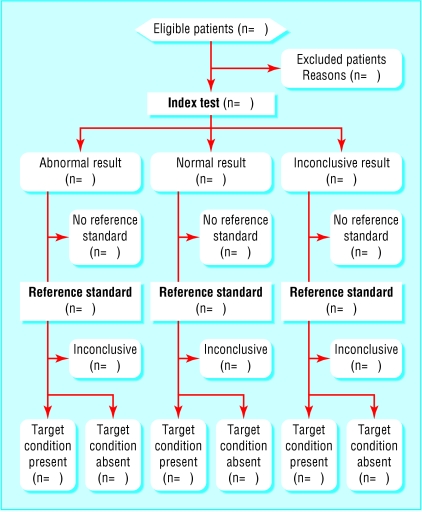

A flow diagram provides information about the method of patient recruitment (for example, enrolment of a consecutive series of patients with specific symptoms or of cases and controls), the order of test execution, and the number of patients undergoing the test under evaluation (index test) and the reference test. The figure shows a prototype flowchart that reflects the most commonly employed design in diagnostic research. Examples that reflect other designs appear on the STARD website (www.consort-statement.org\stardstatement.htm).

Discussion

The purpose of the STARD initiative is to improve the quality of reporting of diagnostic studies. The items in the checklist and flowchart can help authors to describe essential elements of the design and conduct of the study, the execution of tests, and the results. We arranged the items under the usual headings of a medical research article, but this is not intended to dictate the order in which they have to appear within an article.

The guiding principle in the development of the STARD checklist was to select items that would help readers judge the potential for bias in the study and to appraise the applicability of the findings. Two other general considerations shaped the content and format of the checklist. Firstly, the STARD group believes that one general checklist for studies of diagnostic accuracy, rather than different checklists for each field, is likely to be more widely disseminated and perhaps accepted by authors, peer reviewers, and journal editors. Although the evaluation of imaging tests differs from that of tests in the laboratory, we felt that these differences were more in degree than in kind. The second consideration was the development of a checklist specifically aimed at studies of diagnostic accuracy. We did not include general issues in the reporting of research findings, such as the recommendations contained in the uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals.14

Wherever possible, the STARD group based the decision to include an item on evidence linking the item to biased estimates (internal validity) or to variations in measures of diagnostic accuracy (external validity). The evidence varied from narrative articles that explained theoretical principles and papers that presented the results of statistical modelling to empirical evidence derived from diagnostic studies. For several items, the evidence was rather limited.

A separate background document explains the meaning and rationale of each item and briefly summarises the type and amount of evidence.15 This background document should enhance the use, understanding, and dissemination of the STARD checklist.

The STARD group put considerable effort into the development of a flow diagram for diagnostic studies. A flow diagram has the potential to communicate vital information about the design of a study and the flow of participants in a transparent manner.16 A comparable flow diagram has become an essential element in the CONSORT standards for reporting of randomised trials.12,16 The flow diagram could be even more essential in diagnostic studies, given the variety of designs employed in diagnostic research. Flow diagrams in the reports of studies of diagnostic accuracy indicate the process of sampling and selecting participants (external validity); the flow of participants in relation to the timing and outcomes of tests; the number of subjects who fail to receive the index test or the reference standard, or both (potential for verification bias17–19); and the number of patients at each stage of the study, which provides the correct denominator for proportions (internal consistency).

The STARD group plans to measure the impact of the statement on the quality of published reports on diagnostic accuracy with a before and after evaluation.13 Updates of the STARD initiative's documents will be provided when new evidence on sources of bias or variability becomes available. We welcome any comments, whether on content or form, to improve the current version.

Supplementary Material

Table.

STARD checklist for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies

| Section and topic

|

Item

|

Description

|

|---|---|---|

| Title, abstract, and keywords | 1 | Identify the article as a study of diagnostic accuracy (recommend MeSH heading “sensitivity and specificity”) |

| Introduction | 2 | State the research questions or aims, such as estimating diagnostic accuracy or comparing accuracy between tests or across participant groups |

| Methods: | ||

| Participants | 3 | Describe the study population: the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the settings and locations where the data were collected |

| 4 | Describe participant recruitment: was this based on presenting symptoms, results from previous tests, or the fact that the participants had received the index tests or the reference standard? | |

| 5 | Describe participant sampling: was this a consecutive series of participants defined by selection criteria in items 3 and 4? If not, specify how participants were further selected | |

| 6 | Describe data collection: was data collection planned before the index tests and reference standard were performed (prospective study) or after (retrospective study)? | |

| Test methods | 7 | Describe the reference standard and its rationale |

| 8 | Describe technical specifications of material and methods involved, including how and when measurements were taken, or cite references for index tests or reference standard, or both | |

| 9 | Describe definition of and rationale for the units, cut-off points, or categories of the results of the index tests and the reference standard | |

| 10 | Describe the number, training, and expertise of the persons executing and reading the index tests and the reference standard | |

| 11 | Were the readers of the index tests and the reference standard blind (masked) to the results of the other test? Describe any other clinical information available to the readers. | |

| Statistical methods | 12 | Describe methods for calculating or comparing measures of diagnostic accuracy and the statistical methods used to quantify uncertainty (eg 95% confidence intervals) |

| 13 | Describe methods for calculating test reproducibility, if done | |

| Results: | ||

| Participants | 14 | Report when study was done, including beginning and ending dates of recruitment |

| 15 | Report clinical and demographic characteristics (eg age, sex, spectrum of presenting symptoms, comorbidity, current treatments, and recruitment centre) | |

| 16 | Report how many participants satisfying the criteria for inclusion did or did not undergo the index tests or the reference standard, or both; describe why participants failed to receive either test (a flow diagram is strongly recommended) | |

| Test results | 17 | Report time interval from index tests to reference standard, and any treatment administered between |

| 18 | Report distribution of severity of disease (define criteria) in those with the target condition and other diagnoses in participants without the target condition | |

| 19 | Report a cross tabulation of the results of the index tests (including indeterminate and missing results) by the results of the reference standard; for continuous results, report the distribution of the test results by the results of the reference standard | |

| 20 | Report any adverse events from performing the index test or the reference standard | |

| Estimates | 21 | Report estimates of diagnostic accuracy and measures of statistical uncertainty (e.g. 95% confidence intervals) |

| 22 | Report how indeterminate results, missing responses, and outliers of index tests were handled | |

| 23 | Report estimates of variability of diagnostic accuracy between readers, centres, or subgroups of participants, if done | |

| 24 | Report estimates of test reproducibility, if done | |

| Discussion | 25 | Discuss the clinical applicability of the study findings |

Figure.

Prototype of a flow diagram for a study on diagnostic accuracy

Acknowledgments

This initiative to improve the reporting of studies was supported by a large number of people around the globe who commented on earlier versions. This paper is also being published in the first issues in 2003 of Annals of Internal Medicine, Clinical Chemistry, Journal of Clinical Microbiology, Lancet, and Radiology. Clinical Chemistry is also publishing the background document.

Footnotes

Editorial by Straus

Funding: Financial support to convene the STARD group was provided in part by the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board, Amstelveen, Netherlands; the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry, Milan, Italy; the Medical Research Council's Health Services Research Collaboration, Bristol; and the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Competing interests: None declared.

A list of members of the STARD steering committee and the STARD group appears on bmj.com

References

- 1.Guyatt GH, Tugwell PX, Feeny DH, Haynes RB, Drummond M. A framework for clinical evaluation of diagnostic technologies. Can Med Assoc J. 1986;134:587–594. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Med Decis Making. 1991;11:88–94. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9101100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kent DL, Larson EB. Disease, level of impact, and quality of research methods. Three dimensions of clinical efficacy assessment applied to magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1992;27:245–254. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199203000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griner PF, Mayewski RJ, Mushlin AI, Greenland P. Selection and interpretation of diagnostic tests and procedures. Principles and applications. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:557–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. The selection of diagnostic tests. In: Sackett D, editor. Clinical epidemiology. Boston, Toronto, and London: Little, Brown and Company; 1991. pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8:283–298. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(78)80014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid MC, Lachs MS, Feinstein AR. Use of methodological standards in diagnostic test research. Getting better but still not good. JAMA. 1995;274:645–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelemans PJ, Leiner T, de Vet HCW, van Engelshoven JMA. Peripheral arterial disease: meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of MR angiography. Radiology. 2000;217:105–114. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.1.r00oc11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devries SO, Hunink MGM, Polak JF. Summary receiver operating characteristic curves as a technique for meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of duplex ultrasonography in peripheral arterial disease. Acad Radiol. 1996;3:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(96)80257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lijmer JG, Mol BW, Heisterkamp S, Bonsel GJ, Prins MH, van der Meulen JH, et al. Empirical evidence of design-related bias in studies of diagnostic tests. JAMA. 1999;282:1061–1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, Horton R, Moher D, Olkin I, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276:637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1987–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L. Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials. A comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA. 2001;285:1992–1995. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. JAMA. 1997;277:927–934. http://www.acponline.org/journals/annals/01jan97/unifreqr.htm (accessed 7 Nov 2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. Clin Chem. 2003;49:7–18. doi: 10.1373/49.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egger M, Jüni P, Barlett C. Value of flow diagrams in reports of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2001;285:1996–1999. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.15.1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knottnerus JA. The effects of disease verification and referral on the relationship between symptoms and diseases. Med Decis Making. 1987;7:139–148. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8700700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panzer RJ, Suchman AL, Griner PF. Workup bias in prediction research. Med Decis Making. 1987;7:115–119. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8700700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begg CB. Biases in the assessment of diagnostic tests. Stat Med. 1987;6:411–423. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.