Introduction

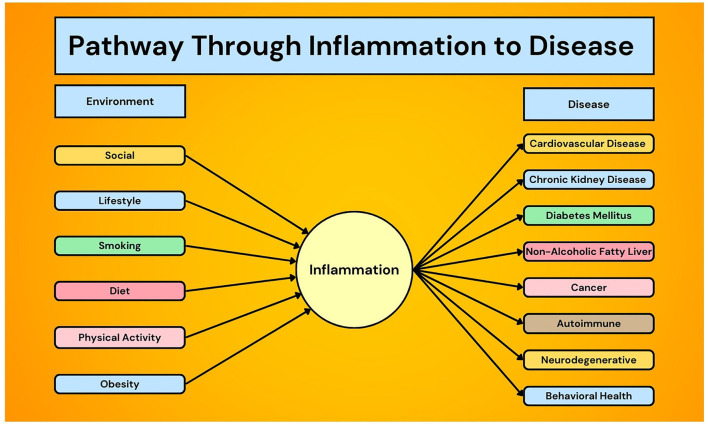

Inflammation is directly associated with the morbidity and mortality of a diverse number of chronic health conditions including cardiovascular disease (1–3), chronic kidney disease (4), diabetes mellitus (5, 6), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (7), cancer (8, 9), autoimmune diseases (10, 11), and neurodegenerative (12) and behavioral health disorders (13) (Figure 1). Not only is inflammation the byproduct of chronic disease, it also has a mechanistic role in the underlying etiology and pharmacoprevention of diseases such as atherosclerosis (14). For example, some of the most common mutations in age-related, clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) increase the expression of inflammatory genes, potentially explaining why CHIP is associated with almost twice the risk of coronary artery disease (15–17).

Figure 1.

Unifying theory of inflammation and chronic disease prevention.

Various acute and chronic factors can modulate inflammation, including infection, the social and physical environments (18), lifestyle (19–21), diet (22, 23), and physical activity (24–27) (Figure 1). A PubMed search of “chronic inflammation” leads to over 170,000 results, and stalwart medical institutions propose diets targeting chronic inflammation (28, 29). Moreover, translating such knowledge to disease therapy has improved outcomes, such as using exercise to reduce inflammation in patients with depression (30), COPD (31), and frailty (32). Despite this, there is a lack of anti-inflammatory guidelines to prevent and treat chronic disease from bench to practice, and a deeper understanding of the complex relationship between inflammation and chronic disease development and progression is needed.

Heart disease and cardiometabolic disease

A body of experimental evidence demonstrates how interferons (IFNs) and IFN-related pathways play important roles both in the inflammation commonly associated with heart disease pathogenesis as well as in the protection against heart disease (Tran et al.). While it is unlikely that measuring a single plasma IFN will be of prognostic significance in managing heart disease, immense advances in single cell technologies are helping elucidate the molecular mechanism of heart disease. Therapeutic, immunosuppressive strategies to reduce IFN or IFN-related pathway signaling come with an increased malignancy and infection risk, and targeting downstream pathways, such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes signaling, may theoretically overcome these side effects by allowing other immune defense pathways to remain intact (Tran et al.). When the advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) was used to assess inflammation in hypertensive patients, it determined that lower levels of inflammation (i.e., higher ALI) were associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular death (Tu et al.). However, because of the way ALI uses body mass index (BMI) in its equation and how high BMI is an established risk factor for cardiovascular death, it is recommended that ALI not be used as a prognostic marker for cardiovascular death in hypertensive patients with BMI ≥35.5 kg/m2.

US adults with undiagnosed cardiometabolic disease have a higher risk of elevated HsCRP (Mainous, Sharma et al.). Furthermore, risk of the metabolic disorder nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was linearly associated with the inflammation-related biomarkers SII, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) and non-linearly associated with platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) when natural logarithm (ln) transformed (Liu et al.). These results further elucidate inflammation's clinical significance in NAFLD may assist with ongoing research to improve diagnosis and treatment options.

Cancer and immunoinflammatory dermatoses

Levels of vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1), a dual-function glycoprotein with an important role in inflammation and tumor progression, was associated with an increased 12-year risk of cancer incidence, cancer mortality, and all-cause mortality in a Taiwanese population, a predictive performance that was better than smoking (Chen et al.). Two inflammation-related biomarkers, systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and product of platelet count and neutrophil count (PPN), were independent risk factors for kidney cancer incidence and may aid in the development of targeted screening strategies for at-risk patients (He et al.). Inflammasomes, immune-functional protein multimers that are closely linked to the host defense mechanism and can activate various inflammatory signaling pathways closely associated with malignancies, have become a novel target of more than 50 natural extracts and synthetic small molecule agents as prospective therapies for common cancers (Gu et al.). Another novel inflammatory target for cancer therapeutics are neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), web-like structures containing DNA and released from the nucleus or mitochondria (Zhong et al.). NETs, important structures in innate immunity and the progression of inflammatory diseases, are being investigated for their role in potentially treating multiple cancers, especially metastatic cancer.

Circulating inflammatory cytokines' role in the development of immunoinflammatory dermatoses offers new prevention and therapeutic targets. In a Mendelian randomization study, both IL-4 and IL-1RA may have inhibitory functions in atopic dermatitis pathogenesis (Li et al.). Conversely, IL-4 and SCGF-b may have promoting functions in the pathogenesis of vitiligo and psoriasis, respectively.

Social environment, diet, and physical activity

A considerable proportion of US adults have elevated inflammation as measured by highly sensitive C-reactive protein (HsCRP), especially minorities and individuals with low socioeconomic status (Mainous, Orlando et al.). While either inflammation or poverty alone each confer about a 50% increased risk in all-cause mortality in US adults aged 40 and older, individuals with both inflammation and poverty have a 127% increased heart disease mortality risk and a 196% increased cancer mortality risk, revealing that the combined effect of inflammation and poverty on mortality is synergistic in this population (Mainous, Orlando et al.). Therefore, both systemic inflammation and poverty could become a focus of primary care for preventing disease and monitoring its progression.

Low-grade chronic inflammation can be initiated and aggravated by specific key dietary factors, particularly sugars and mixed processed foods, the consumption of which has significantly increased over the past 30 years (Ma et al.). The negative impact that a high-sugar diet has on certain autoimmune conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, has been mechanistically linked to its pro-inflammatory effects (Ma et al.). For example, obesity has been strongly associated with low-grade chronic inflammation, but in the case of psoriasis, new research suggests that dietary sugars and fats mediate the inflammatory stimulation of psoriasis rather than obesity itself (Ma et al.). Similarly, physical activity influences inflammation with connections to disease severity. For example, physical activity following surgical resection for colon cancer is associated with a significantly increased disease-free survival, and inflammation has been hypothesized to be the linking factor (Brown et al.). Even though aerobic exercise was not associated with dose-response reductions in HsCRP or IL-6 in a randomized, dose-response trial of 39 stage I-III colon cancer survivors, cancer stage modified the association (Brown et al.). Specifically, exercise was not associated with inflammatory biomarkers in stage I-II disease, and 300 min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (high-dose) was not associated with inflammation in stage III disease, but 150 min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise (low-dose) did reduce HsCRP and IL-6 in stage III disease (Brown et al.). However, the biological reason why cancer stage modifies the association between exercise dose and inflammatory biomarker levels remains unclear and is being prospectively studied in an ongoing randomized trial of exercise in colorectal cancer survivors (NCT03975491).

Conclusion

Inflammation has an established connection with the etiology and progression of numerous major chronic diseases, but no specific guidelines exist for clinicians to use inflammatory markers to guide prevention, diagnosis, or treatment. Equally as important, the opportunity to discover a breakthrough treatment for such common chronic diseases may be right at our fingertips with the mechanistic knowledge of inflammation's role in disease pathogenesis. Future large, prospective clinical trials are needed to further elucidate the findings of mechanistic and observational trials and translate them to the bedside.

Author contributions

FO: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. AM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The co-authors would like to thank Angel Colon for assisting with the creation of Figure 1.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJ, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:2195–207. 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sagris M, Theofilis P, Antonopoulos AS, Oikonomou E, Paschaliori C, Galiatsatos N, et al. Inflammation in coronary microvascular dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:13471. 10.3390/ijms222413471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson K, Fuster V, Ridker PM. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2023) 82:648–60. 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai W, Xie Y, Zhao X, Xu X, Yu S, Lu H, et al. Elevated systemic immune inflammation level increases the risk of total and cause-specific mortality among patients with chronic kidney disease: a large multi-center longitudinal study. Inflamm Res. (2023) 72:149–58. 10.1007/s00011-022-01659-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharif S, Van der Graaf Y, Cramer MJ, Kapelle LJ, de Borst GJ, Visseren FLJ, et al. Low-grade inflammation as a risk factor for cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2021) 20:220. 10.1186/s12933-021-01409-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Chen Y, Gao Q, Wei Q. Association of systemic immune inflammatory index with all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2023) 23:596. 10.1186/s12872-023-03638-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yip TC, Lyu F, Lin H, Li G, Yuen PC, Wong VW, et al. Non-invasive biomarkers for liver inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: present and future. Clin Mol Hepatol. (2023) 29(Suppl):S171–83. 10.3350/cmh.2022.0426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinko D, Diakos CI, Clarke SJ, Charles KA. Cancer-related systemic inflammation: the challenges and therapeutic opportunities for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 102:599–610. 10.1002/cpt.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh-Manoux A, Shipley MJ, Bell JA, Canonico M, Elbaz A, Kivimäki M. Association between inflammatory biomarkers and all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality. CMAJ. (2017) 189:E384–90. 10.1503/cmaj.160313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn SS, Yoo J, Jung SM, Song JJ, Park YB, Lee SW. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes between patients with early and delayed lupus nephritis. BMC Nephrol. (2020) 21:258. 10.1186/s12882-020-01915-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee LE, Pyo JY, Ahn SS, Song JJ, Park YB, Lee SW. Systemic inflammation response index predicts all-cause mortality in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Int Urol Nephrol. (2021) 53:1631–8. 10.1007/s11255-020-02777-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amanollahi M, Jameie M, Heidari A, Rezaei N. The dialogue between neuroinflammation and adult neurogenesis: mechanisms involved and alterations in neurological diseases. Mol Neurobiol. (2023) 60:923–59. 10.1007/s12035-022-03102-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safari H, Mashayekhan S. Inflammation and mental health disorders: immunomodulation as a potential therapy for psychiatric conditions. Curr Pharm Des. (2023) 29:2841–52. 10.2174/0113816128251883231031054700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feinstein MJ. Statins, inflammation, and tissue context in REPRIEVE. JAMA Cardiol. (2024) 9:334–5. 10.1001/jamacardio.2023.5671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, Gibson CJ, Bick AG, Shvartz E, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:111–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaiswal S, Libby P. Clonal haematopoiesis: connecting ageing and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. (2020) 17:137–44. Erratum in: Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020 17:828. 10.1038/s41569-020-0414-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathan DI, Dougherty M, Bhatta M, Mascarenhas J, Marcellino BK. Clonal hematopoiesis and inflammation: a review of mechanisms and clinical implications. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2023) 192:104187. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDade TW, Ryan C, Jones MJ, MacIsaac JL, Morin M, Meyer JM, et al. Social and physical environments early in development predict DNA methylation of inflammatory genes in young adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2017) 114:7611–6. 10.1073/pnas.1620661114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng J, Liu M, Zhao L, Hébert JR, Steck SE, Wang H, et al. Dietary inflammatory potential, inflammation-related lifestyle factors, and incident anxiety disorders: a prospective cohort study. Nutrients. (2023) 16:121. 10.3390/nu16010121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruckner F, Gruber JR, Ruf A, Edwin Thanarajah S, Reif A, Matura S. Exploring the link between lifestyle, inflammation, and insulin resistance through an improved healthy living index. Nutrients. (2024) 16:388. 10.3390/nu16030388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Song M, Yang Z, Huang X, Lin Y, Yang H. Healthy lifestyles, systemic inflammation, and breast cancer risk: a mediation analysis. BMC Cancer. (2024) 24:208. 10.1186/s12885-024-11931-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuguang L, Chang Y, Li H, Li F, Zou Q, Liu X, et al. Inflammation mediates the relationship between diet quality assessed by healthy eating index-2015 and metabolic syndrome. Front Endocrinol. (2024) 15:1293850. 10.3389/fendo.2024.1293850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Feng Y, Yang X, Li Y, Wu Y, Yuan L, et al. Dose-response association of dietary inflammatory potential with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Adv Nutr. (2022) 13:1834–45. 10.1093/advances/nmac049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fedewa MV, Hathaway ED, Ward-Ritacco CL. Effect of exercise training on C reactive protein: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. (2017) 51:670–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-095999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metsios GS, Moe RH, Kitas GD. Exercise and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. (2020) 34:101504. 10.1016/j.berh.2020.101504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Wu X, Bai Y, Wei W, Li G, Fu M, et al. Physical activity attenuates the associations of systemic immune-inflammation index with total and cause-specific mortality among middle-aged and older populations. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:12532. 10.1038/s41598-021-91324-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurochkina NS, Orlova MA, Vigovskiy MA, Zgoda VG, Vepkhvadze TF, Vavilov NE, et al. Age-related changes in human skeletal muscle transcriptome and proteome are more affected by chronic inflammation and physical inactivity than primary aging. Aging Cell. (2024) 23:e14098. 10.1111/acel.14098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johns Hopkins Medicine . Healthy Eating Tips to Ease Chronic Inflammation. (2024). Available online at: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/healthy-eating-tips-to-ease-chronic-inflammation (accessed April 25, 2024).

- 29.Harvard Health Publishing – Harvard Medical School . Foods that Fight Inflammation. (2024). Available online at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/foods-that-fight-inflammation (accessed April 25, 2024).

- 30.Paolucci EM, Loukov D, Bowdish DME, Heisz JJ. Exercise reduces depression and inflammation but intensity matters. Biol Psychol. (2018) 133:79–84. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moy ML, Teylan M, Danilack VA, Gagnon DR, Garshick E. An index of daily step count and systemic inflammation predicts clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2014) 11:149–57. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-243OCorlaf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadjapong U, Yodkeeree S, Sungkarat S, Siviroj P. Multicomponent exercise program reduces frailty and inflammatory biomarkers and improves physical performance in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3760. 10.3390/ijerph17113760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]