Abstract

Background

Frailty is increasingly present in patients with acute myocardial infarction. The electronic Frailty Index (eFI) is a validated method of identifying vulnerable older patients in the community from routine primary care data. Our aim was to assess the relationship between the eFI and outcomes in older patients hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction.

Study design and setting

Retrospective cohort study using the DataLoch Heart Disease Registry comprising consecutive patients aged 65 years or over hospitalised with a myocardial infarction between October 2013 and March 2021.

Methods

Patients were classified as fit, mild, moderate, or severely frail based on their eFI score. Cox-regression analysis was used to determine the association between frailty category and all-cause mortality.

Results

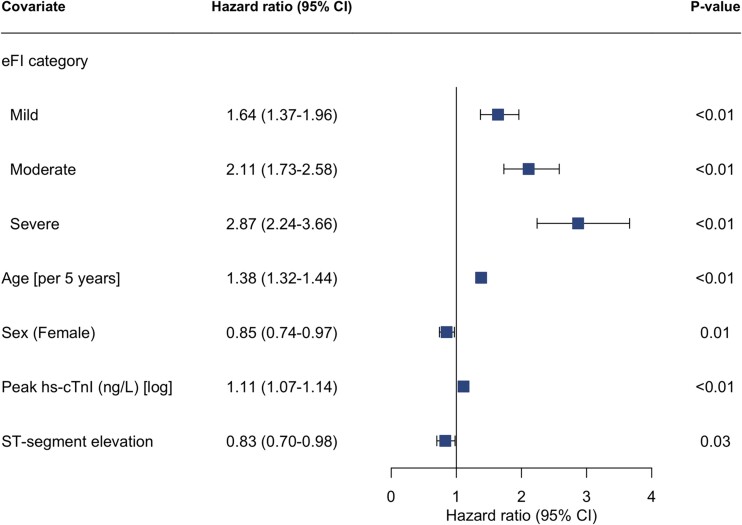

In 4670 patients (median age 77 years [71–84], 43% female), 1865 (40%) were classified as fit, with 1699 (36%), 798 (17%) and 308 (7%) classified as mild, moderate and severely frail, respectively. In total, 1142 patients died within 12 months of which 248 (13%) and 147 (48%) were classified as fit and severely frail, respectively. After adjustment, any degree of frailty was associated with an increased risk of all-cause death with the risk greatest in the severely frail (reference = fit, adjusted hazard ratio 2.87 [95% confidence intervals 2.24 to 3.66]).

Conclusion

The eFI identified patients at high risk of death following myocardial infarction. Automatic calculation within administrative data is feasible and could provide a low-cost method of identifying vulnerable older patients on hospital presentation.

Keywords: frailty, myocardial infarction, electronic frailty index, routine data, older people

Key Points

Frailty is common in acute myocardial infarction.

The electronic frailty index can identify patients at high risk of adverse health outcomes following myocardial infarction.

The electronic frailty index could be used to guide targeted frailty interventions in myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Developing effective methods to manage an ageing and increasingly frail society represents one of the greatest challenges facing healthcare systems. This is particularly relevant for cardiology services: cardiovascular disease is the most prevalent condition in older adults with the majority of patients who suffer a myocardial infarction over the age of 70 years [1–3].

Frailty, a state of increased vulnerability, is common amongst patients with cardiovascular disease and is a strong independent predictor of poor clinical outcomes in numerous cardiovascular conditions, including myocardial infarction [4–7]. Guideline-recommended management recommends the use of individualised risk stratification with consideration of factors beyond a patient’s chronological age, including frailty [7, 8]. Despite this, frailty is rarely systematically or objectively measured, nor routinely used to identify high risk patients. This may in part be due to the challenges of frailty assessment in acute illness, where a patient’s ability to perform physical or mental tasks may be impaired [9]. Comprehensive assessment can be time-consuming, requiring additional resources, and subjective clinician assessment may overestimate frailty in cardiovascular patients, with agreement shown to vary based on clinician experience [10, 11].

The electronic Frailty Index (eFI) uses primary care data to identify and classify frailty. The eFI has been validated in large community-based populations aged 65 years old and over as a predictor of unplanned hospital admission and all-cause mortality at 1, 3 and 5 years, with good correlation with in-person frailty assessment [12–15]. However, the performance of the eFI in those hospitalised with myocardial infarction, and its ability to predict individual patient outcomes in an acute setting, is unclear.

Our aim was to evaluate the association between frailty, identified and stratified using the eFI, and the management and outcomes of patients admitted to hospital with myocardial infarction.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study using routinely collected electronic healthcare data collated in the DataLoch Heart Disease Registry. This registry consists of patients with cardiovascular disease in the South-East of Scotland [16]. Consecutive patients admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction between October 1st 2013 and March 1st 2021 were included. Myocardial infarction was defined using International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) code I21 or I22 recorded in position one or two of the discharge coding [17]. In the case of multiple hospital admissions, the index event was defined as the earliest recorded episode. Patients under the age of 65 years on the date of index presentation were excluded.

The study was performed with approval of the local Research Ethics Committee and Caldicott Guardian in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Electronic frailty index

Primary care Read codes (a standardised coding system for recording patient characteristics, symptoms, signs, diseases, disabilities, laboratory test results, and information about social circumstances) were used to calculate the eFI 24 h prior to the index hospital admission [12]. Read codes were used to identify the presence or absence of 36 deficits grouped across four domains: eighteen disease states, nine symptoms or signs, eight markers of disability, one abnormal laboratory value (Appendix). The number of deficits present per patient was divided by 36 to produce a score from 0 to 1. A patient was deemed frail if the score was ≥0.12 with the degree of frailty further divided in to mild (0.12–0.24), moderate (0.25–0.36) and severe (>0.36) [12].

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality at 12 months from the index presentation. Secondary outcomes included: in-patient all-cause mortality; unplanned hospital admission due to non-fatal myocardial infarction or urgent coronary revascularisation, heart failure, stroke, or major bleeding within 12 months of discharge; cardiovascular death at 12 months; and all-cause mortality at 3-years.

Data sources

National data registering deaths (National Records of Scotland), medical prescriptions (Prescribing Information System) and inpatient activity (Scottish Morbidity Record) were used to identify outcomes. The Charlson Comorbidity Index was calculated using ICD-10 codes [18]. Provision of pharmacological therapies were determined from community prescription records at 30-days post-discharge. To reduce survival bias, all reporting of medical prescriptions was restricted to patients alive at this time point. Hospital admission with recurrent myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke or major bleeding were identified using HDRUK phenotypes [19]. Major bleeding was defined as the occurrence of any bleed meeting the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) Type 3 or Type 5 criteria [20]. Cardiovascular death was defined where any of the following ICD-10 codes were listed as the primary cause of death: I10-I15, I20-I25, I44-I51, I61, I62.0, I62.9, I63.0-I63.5, I63.8, I63.9, I64-I67 and I70-I73.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were stratified according to eFI categories. Continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and 25th–75th centile where skewed. Categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and percentages (%). Comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test and Pearson’s Chi-squared test where appropriate. Any categorical variables with a frequency of less than 5 are reported as ‘<5’ due to data protection requirements.

Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the relationship between eFI categories and all-cause death as an inpatient, at 12 months and at 3 years, and cardiovascular death at 12 months. For the outcome of cardiovascular death, the competing risk of non-cardiovascular death was accounted for using a Fine-Gray sub distribution hazard model [21]. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between frailty category, inpatient mortality, and unplanned hospital admission. We estimated all models with and without adjustment for age, sex, myocardial infarction classification (non-ST elevation vs ST-elevation myocardial infarction) and maximal cardiac troponin value recorded during the index admission. [22] Cardiac troponin was measured using the ARCHITECTSTAT high-sensitivity troponin I assay and maximal troponin values were log transformed (log base 10).

Discrimination of the eFI score for the primary outcome was determined by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) with calibration assessed visually using a calibration plot.

In subgroup analysis, we assessed the associated hazard of eFI categories by age (<75 vs ≥75 years), sex (male vs female) and the presence or absence of ST-segment elevation including testing for interaction.

All analysis was performed using remote access to deidentified data within a Secure Data Environment (DataLoch, Edinburgh, United Kingdom) and conducted using R (version 4.2.0; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Study population

A total of 4670 of the 8038 identified patients were eligible for inclusion after those younger than 65 years (n = 3368) were excluded. The median follow-up time was 3.0 (IQR, 1.1 to 5.3) years.

Of the 4670 patients (median age 77 [71–84] years, 43% female, 83% white), a total of 1865 (40%) were classified as fit with 1699 (36%), 798 (17%) and 308 (7%) classified as mild, moderate and severely frail respectively. Frail patients were older and more likely to be female (Table 1). Compared with fit patients, patients with severe frailty had a significantly greater prevalence of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities including previous myocardial infarction (41% versus 11%), heart failure (46% versus 4%), chronic kidney disease (45% versus 15%), dementia (19% versus 2%) and a Charlson Comorbidity Index of 2 or more (46% versus 3%, P < .01 for all).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and patient management

| Overall | electronic Frailty Index Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit | Mild | Moderate | Severe | P-value | ||

| N | 4670 | 1865 | 1699 | 798 | 308 | |

| Patient demographics | ||||||

| Age (years) | 77 [71–84] | 72 [68–78] | 79 [72–85] | 81 [75–86] | 82 [78–88] | <.001 |

| Female | 2014 (43%) | 645 (35%) | 784 (46%) | 406 (51%) | 179 (58%) | <.001 |

| White | 3865 (83%) | 1419 (76%) | 1449 (85%) | 707 (89%) | 290 (94%) | <.001 |

| Deprivation (SIMD 1st quintile) | 648 (14%) | 204 (11%) | 235 (14%) | 148 (19%) | 61 (20%) | <.001 |

| Chest pain as presenting symptom | 3680 (82%) | 1567 (87%) | 1326 (81%) | 568 (74%) | 219 (73%) | <.001 |

| Past medical history | ||||||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 1989 (43%) | 418 (22%) | 805 (47%) | 522 (65%) | 244 (79%) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1061 (23%) | 213 (11%) | 434 (26%) | 287 (36%) | 127 (41%) | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 772 (17%) | 68 (3.6%) | 274 (16%) | 288 (36%) | 142 (46%) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 838 (18%) | 98 (5.3%) | 323 (19%) | 277 (35%) | 140 (45%) | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 558 (12%) | 73 (3.9%) | 227 (13%) | 173 (22%) | 85 (28%) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1139 (24%) | 206 (11%) | 446 (26%) | 325 (41%) | 162 (53%) | <.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1249 (27%) | 286 (15%) | 494 (29%) | 331 (41%) | 138 (45%) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 2964 (63%) | 930 (50%) | 1029 (61%) | 497 (62%) | 187 (61%) | <.001 |

| Dementia | 344 (7%) | 40 (2%) | 130 (7.7%) | 115 (14%) | 59 (19%) | <.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index >2 | 743 (16%) | 65 (3%) | 254 (15%) | 282 (35%) | 142 (46%) | <.001 |

| Haematology and clinical chemistry | ||||||

| Haemoglobin, g/L | 132 [118–145] | 139 [127–150] | 129 [116–143] | 124 [110–136] | 119 [106–131] | <.001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min¶ | 70 [49–84] | 77 [65–89] | 68 [47–82] | 53 [36–72] | 48 [32–70] | <.001 |

| Peak high sensitivity troponin I, ng/L (log) | ||||||

| NSTEMI | 7.02 [5.24–8.63] | 7.10 [5.27–8.66] | 7.06 [5.32–8.67] | 6.92 [5.23–8.61] | 6.35 [4.66–8.18] | .02 |

| STEMI | 9.86 [8.22–10.82] | 9.96 [8.35–10.82] | 9.85 [8.18–10.82] | 9.45 [7.94–10.82] | 9.71 [7.98–10.82] | .08 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||

| NSTEMI | 3262 (70%) | 1075 (58%) | 1264 (74%) | 656 (82%) | 267 (87%) | <.001 |

| STEMI | 1408 (30%) | 790 (42%) | 435 (26%) | 142 (18%) | 41 (13%) | |

| Primary treating speciality | ||||||

| Cardiology | 3146 (67%) | 1586 (85%) | 1097 (65%) | 364 (46%) | 99 (32%) | <.001 |

| Medical therapy* | ||||||

| Aspirin | 2587 (65%) | 1292 (76%) | 837 (59%) | 340 (54%) | 118 (52%) | <.001 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 3020 (75%) | 1411 (83%) | 1044 (73%) | 420 (66%) | 145 (63%) | <.001 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy† | 2318 (58%) | 1208 (71%) | 736 (52%) | 281 (44%) | 93 (41%) | <.001 |

| Anticoagulation‡ | 340 (9%) | 90 (5.3%) | 136 (9.5%) | 83 (13%) | 31 (14%) | <.001 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 2067 (52%) | 1061 (63%) | 695 (49%) | 248 (39%) | 63 (28%) | <.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 2065 (52%) | 1013 (60%) | 677 (47%) | 294 (47%) | 81 (35%) | <.001 |

| Lipid lowering therapy | 2544 (64%) | 1305 (77%) | 837 (59%) | 303 (48%) | 99 (43%) | <.001 |

| Revascularisation | ||||||

| Coronary angiography | 2654 (57%) | 1452 (78%) | 881 (52%) | 265 (33%) | 56 (18%) | <.001 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 1993 (43%) | 1138 (61%) | 622 (37%) | 195 (24%) | 38 (12%) | <.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 151 (3%) | 86 (5%) | 46 (3%) | 15 (2%) | <5 | <.001 |

Presented as number (%), mean (±SD) or median [25th percentile, 75th percentile].

Abbreviations: SIMD = Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation, CCI = Charlson comorbidity index, ACE = Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = Angiotensin receptor blocker; NSTEMI = non-ST elevation myocardial infarction; STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

¶Value missing in 1469 patients.

*Restricted to those alive at 30-days post-discharge (overall = 4074; fit = 1707; mild = 1465; moderate = 660; severe = 242).

†Two medications from aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor.

‡Includes warfarin or novel anticoagulants.

Patient management

There was an inverse dose–response relationship with frailty severity, with treatment rates lowest in those with severe frailty. Patients with any degree of frailty were less likely to be managed on a cardiology ward, undergo invasive coronary angiography or revascularization, or be prescribed guideline recommended pharmacological therapy (Table 1). Rates of coronary angiography were lowest in those with severe frailty (12% versus 78% fit).

Primary outcome

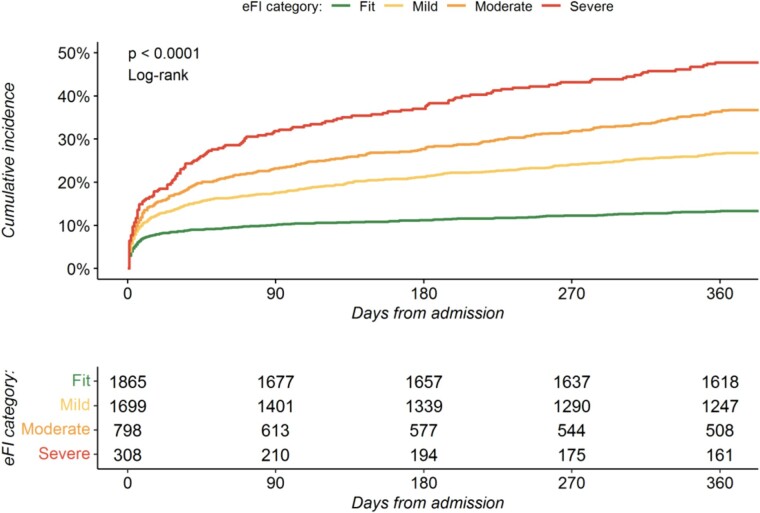

In total, 1142 (24%) patients died within 12 months of admission of whom 248 (13%), 454 (27%), 293 (37%) and 147 (47%) were classified as fit, mild, moderate and severely frail respectively (Table 2, Fig. 1). After adjustment, the eFI was independently associated with all-cause death at 12 months, with the risk greatest in those with severe frailty (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.87; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.24–3.66) (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1). The eFI score was adequately calibrated and achieved modest discrimination (AUC 0.67, 95% CI 67–70) for the primary outcome (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Table 2.

Patient outcomes by electronic frailty index category

| Overall | electronic Frailty Index Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit | Mild | Moderate | P-value | |||

| N | 4670 | 1865 | 1699 | 798 | 308 | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| All-cause death at 12 months | 1142 (24%) | 248 (13%) | 454 (27%) | 293 (37%) | 147 (48%) | <.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Duration of stay >5 days | 1692 (36%) | 531 (28%) | 650 (38%) | 365 (46%) | 146 (47%) | <.001 |

| All-cause death during index presentation | 585 (13%) | 148 (7.9%) | 230 (14%) | 137 (17%) | 70 (23%) | <.001 |

| Recurrent hospital admission† | 1253 (27%) | 400 (21%) | 476 (28%) | 275 (34%) | 102 (33%) | <.001 |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction orurgent revascularisation | 1112 (24%) | 379 (20%) | 425 (25%) | 225 (28%) | 83 (27%) | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 100 (2%) | 8 (<1%) | 40 (2%) | 39 (5%) | 13 (4%) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 18 (<1%) | 5 (<1%) | 5 (<1%) | 5 (<1%) | <5 (<5%) | <.001 |

| Major bleeding | 67 (1%) | 20 (1%) | 19 (1%) | 21 (3%) | 7 (2%) | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular death at 12 months | 796 (17%) | 190 (10%) | 314 (18%) | 190 (24%) | 102 (33%) | <.001 |

| All-cause death at 3 years* | 1698 (36%) | 360 (19%) | 685 (40%) | 446 (56%) | 207 (67%) | <.001 |

Presented as number (%)

Abbreviations: ACE = Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = Angiotensin receptor blocker

†due to non-fatal myocardial infarction or urgent revascularisation, heart failure episode, stroke, or major bleeding event within 12 months

*Number of patients with minimum 3-year follow-up = 4006 (eFI category: fit = 1609; mild = 1456; moderate = 676; severe = 265)

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality at 12 months. Cumulative incidence plot of 12-month all-cause mortality by electronic frailty index classification.

Figure 2.

Electronic frailty index and risk of all-cause mortality. Forest plot of cox-regression analysis assessing the associated hazard for all-cause mortality within 12 months of admission by electronic frailty index category (reference = fit). Model adjusted for age, sex, peak troponin value, and myocardial infarction classification (NSTEMI vs STEMI). eFI = electronic frailty index, hs-cTnI = high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I.

Secondary outcomes

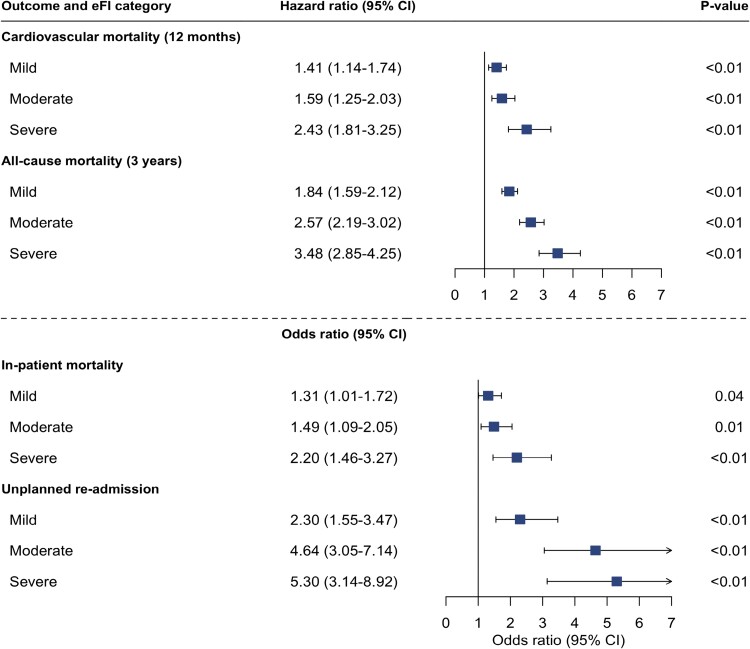

Frailty was associated with an increased incidence of in-patient death, unplanned hospital admission, cardiovascular mortality at 12 months, and all-cause mortality at 3 years (Table 2). The incidence of each outcome increased in line with escalating frailty category and was highest in those with severe frailty.

Any degree of frailty was associated with an increased odds of both in-patient death and unplanned hospital admission with the odds greatest in those with severe frailty (reference = fit; adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.20 [95% CI 1.46–3.27] and OR 5.30 [95% CI 3.14–8.92], respectively, P < .001 for both) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3.

Electronic frailty index and additional adverse outcomes following myocardial infarction. Forest plot showing output of cox-regression and logistic regression analysis assessing the association of electronic frailty index categories with cardiovascular mortality within 12 months, all-cause mortality at 3 years, in-patient all-cause mortality, and unplanned hospital re-admission within 12-months of discharge. Adjusted for age, sex, peak troponin value and myocardial infarction classification (NSTEMI vs STEMI).

Cardiovascular death was the primary cause of death across all frailty categories. In total, 796 (70%) of all deaths were due to a cardiovascular cause of which 190 (10%) and 102 (33%) occurred in fit and severely frail patients, respectively. Patients with severe frailty had a persisting but attenuated risk of cardiovascular death (adjusted HR 2.43 [95% CI 1.81–3.25]) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3).

At 3 years, 207 (67%) patients classified as severely frail had died compared with 360 (19%) classified as fit. The risk of death within 3 years was greatest in those with severe frailty (adjusted HR 3.48; 95% CI 2.85–4.25) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S3).

Subgroup analysis

The associated hazard of all-cause death was similar across frailty categories when stratified by sex or a final diagnosis of non-ST-segment elevation or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. In patients classified as severely frail, those aged <75 years had a two-fold adjusted increase in the risk of all-cause mortality at 12 months compared to those aged ≥75 years (HR 5.17 [95% CI 2.94–9.12] versus 2.48 [95% CI 1.88–3.26]) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

In 4670 consecutive older patients with a diagnosis of myocardial infarction, we have measured frailty using the eFI and determined its relationship with key outcomes. We report several findings important to clinical practice. First, frailty is common in older patients with myocardial infarction, affecting over half of our study population of which 1 in 10 were classified as severely frail. Second, we were able to quantify frailty in all enrolled patients using linked routine electronic healthcare data. Third, frailty classified using the eFI was independently associated with key adverse outcomes following myocardial infarction including short and long-term all-cause mortality. Over half of patients classified as severely frail died within 12 months, increasing to more than three quarters at three years. Our findings highlight the scale and impact of frailty in older patients with myocardial infarction and the potential value of using routinely available healthcare data to systematically calculate prognostic tools in real-time to inform clinical care.

Our understanding of cardiovascular disease has evolved rapidly over the last decade resulting in a reduction in age-specific cardiovascular mortality [23, 24]. In comparison, our understanding of how best to manage frail patients has changed little. Research to date has focused on the treatment of single disease processes in isolation despite the majority of patients encountered in clinical practice suffering from multiple interacting health conditions. Population ageing and the resulting increase in multimorbidity and frailty will profoundly impact healthcare services. If we are to develop tools to aid the management of these complex patients, we first need a valid, efficient and easily implementable measure of frailty that corresponds to meaningful patient outcomes.

We were able to calculate the eFI in all patients and demonstrate an independent association with the risk of both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular specific outcomes. Our finding of an approximately 3-fold adjusted increase in the risk of death within 1-year in those classified as severely frailty is consistent with evaluations using other frailty assessment tools [4, 12, 25–27]. Importantly, an increased risk of death was observed across all frailty categories, including in those classified with mild frailty, and was irrespective of age, sex, or markers of infarct severity. Interestingly, we observed that a classification of severe frailty conferred a two-fold greater risk of all-cause death in patients under 75 years compared to those aged 75 years and over, a finding reported by others and one that highlights the utility of frailty assessment outside the very old [4].

In our cohort of consecutive patients, over half were classified as frail using the eFI. This proportion is likely to increase over the coming decades. The prevalence of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease varies considerably, from 4.7% in clinical trial populations to 60% in observational registries [28, 29]. The eFI includes several risk factors for coronary artery disease, which may lead to a greater proportion of patients within our cohort being classified as frail. However, this reflects the importance of cardiovascular disease as both a cause and consequence of frailty [30, 31].

As observed previously, patients with frailty were less likely to receive invasive management in comparison to non-frail patients with fewer than 1 in 10 severely frail patients undergoing angiography compared to in 8 in 10 non-frail patients [4, 32, 33]. There are several explanations for this. First, older frail patients are less likely to present with typical symptoms or signs of ischaemia on 12-lead electrocardiogram and the specificity of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin is decreased making the diagnosis challenging [34]. Second, older adults are under-represented in randomised trials and the benefits and risks of established therapies, as well as how these factors are attenuated by co-existing multimorbidity and frailty, are unclear [35–40]. Finally, there may be a perception that any benefit gained from therapies is outweighed by the competing risk of death or disability as a result of non-cardiovascular conditions more common in an older population that are not modifiable by available cardiovascular therapies. Our observation that the majority of deaths across all frailty categories were due to cardiovascular causes, with a comparatively low rate of non-cardiovascular death that remained constant following admission, challenges this concept and highlights the previously described treatment paradox: those who are at greatest risk of cardiovascular death are the least likely to receive treatment proven to reduce this outcome. Further trials including patients more representative of those seen in clinical practice are needed to ascertain optimal treatment strategies for frail older adults.

There is currently no gold standard method of frailty assessment [41]. We chose to assess the eFI for several reasons. First, frailty assessment using electronic health care data has several advantages over traditional in person assessment, notably reduced risk of observer bias, ease of implementation, reproducibility, and the potential to measure frailty at scale with minimal resources by embedding automatic calculation within digital health records. This approach is feasible, with automatic calculation of the eFI within digital health records already successfully implemented across the National Healthcare Service in the United Kingdom. Second, the eFI uses primary care Read codes. Frailty is a result of impairment across multiple domains including deficits in physical status which may not be captured when using secondary care ICD-10 codes alone. Third, the greater frequency of interaction with primary care services enables repeat calculation over time, allowing changes in frailty status to be observed, which could offer insight on the impact of specific interventions, such as cardiac rehabilitation. Finally, the eFI has been successfully translated and used in international cohorts with alternative primary care coding systems, increasing the utility and applicability of our findings [42].

It remains unclear how the growing body of evidence demonstrating the importance of frailty in patients with myocardial infarction should be translated in to meaningful improvements in clinical care. Although the eFI provided important prognostic information, we observed only modest discrimination for all-cause mortality, suggesting its role in individualised risk stratification may be limited [43]. Discrimination was lower than that achieved in contemporary cohorts when applying the current gold standard cardiovascular risk prediction tool, the GRACE score [8, 44, 45]. This is not surprising, given the eFI was not designed as an individual risk prediction tool. However, the addition of frailty measures to the GRACE score has been shown to improve risk prediction in older patients. [46–48] The ability to routinely identify the most vulnerable patients, at the time of admission, could aid the use of targeted frailty intervention services, inform treatment goals, or prompt discussions on advanced care planning to optimise quality and end-of life care [49]. However, such approaches would depend upon integrated primary and secondary electronic health record systems that are difficult to implement. Tailored cardiac rehabilitation programmes have demonstrated modest improvement in frailty measures in patients with cardiovascular disease [9]. Whether interventions to reduce or impede the progression of frailty can prevent the escalating risk of death seen in those with more pronounced symptoms remains unclear.

Study limitations

There are several limitations of this study. First, our analysis is restricted to patients treated in Scotland and may not be representative of other healthcare systems. However, our findings are in keeping with those from comparable studies across a variety of geographical settings [4, 32, 47]. Second, while the accuracy of ICD-10 coding is regularly audited and has been shown to be of a standard sufficient for use in research, we cannot exclude cases of misclassification [50]. Third, data were limited to variables present within the DataLoch Heart Disease Registry. We were therefore unable to assess the impact of additional key variables known to be associated with prognosis, such as ejection fraction and GRACE score. Fourth, the eFI relies on patients interacting with their primary care physician and the accurate documentation of conditions. This may result in under reporting of frailty and misclassification of severity. Lastly, we were unable to explore the relationship between the eFI and other outcomes of interest, such as functional or cognitive decline.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the electronic Frailty Index identified patients at increased risk of death and major adverse cardiovascular events following myocardial infarction. Measurement of frailty from linked healthcare data is feasible and could provide a low-cost method of identifying vulnerable older patients on hospital presentation.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Matthew T H Lowry, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Dorien M Kimenai, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Dimitrios Doudesis, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Konstantin Georgiev, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Michael McDermott, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Anda Bularga, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Caelan Taggart, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Ryan Wereski, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Amy V Ferry, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Stacey D Stewart, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Christopher Tuck, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

David E Newby, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Nicholas L Mills, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK; Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Atul Anand, BHF Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

M.T.H.L. is supported by a Clinical Research Training Fellowships from the Medical Research Council (MR/W000598/1). D.M.K. is supported by a British Heart Foundation Intermediate Basic Science Research Fellowship (FS/IBSRF/23/25161). C.T. is supported by a British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowship (FS/CRTF/21/2473). R.W. is supported by Clinical Research Training Fellowship (MR/V007017/1) from the Medical Research Council. N.L.M. and D.E.N. are supported by the British Heart Foundation through Chair (CH/F/21/90010 and CH/09/002), Programme Grant (RG/20/10/34966 and RG/F/22/110093) and Research Excellence Awards (RE/18/5/34216). The funders played no role in the design, conduct, data collection, analysis or reporting of the trial.

References

- 1. NICOR . Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP): 2020 Summary Report https://www.nicor.org.uk/national-cardiac-audit-programme/previous-reports/heart-attack-minap-1/201819/myocardial-ischaemia-national-audit-project-minap-final?layout=default(2020, accessed 12th July 2024).

- 2. BHF . Heart & Circulatory Disease Statistics 2022. https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics/heart-statistics-publications/cardiovascular-disease-statistics-2022(2022, accessed 12th July 2024).

- 3. Singh M, Stewart R, White H. Importance of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1726–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ekerstad N, Javadzadeh D, Alexander KPet al. . Clinical frailty scale classes are independently associated with 6-month mortality for patients after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2021;11:89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe Set al. . Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liperoti R, Vetrano DL, Palmer Ket al. . Association between frailty and ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walker D, Gale C, Lip Get al. . Editor’s choice - frailty and the management of patients with acute cardiovascular disease: a position paper from the acute cardiovascular care association. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2018;7:176–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collet J-P, Thiele H, Barbato Eet al. . 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2020;42:1289–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ijaz N, Buta B, Xue QLet al. . Interventions for frailty among older adults with cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;79:482–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kempen JA, Melis RJ, Perry Met al. . Diagnosis of frailty after a comprehensive geriatric assessment: differences between family physicians and geriatricians. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:240–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heaney C, Vuthoori RK, Gibson Get al. . Abstract 13848: assessment of frailty in patients with advanced heart failure before and after LVAD implantation. Circulation 2019;140:A13848–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clegg A, Bates C, Young Jet al. . Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016;45:353–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler Jet al. . Development and validation of a hospital frailty risk score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet 2018;391:1775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brundle C, Heaven A, Brown Let al. . Convergent validity of the electronic frailty index. Age Ageing 2019;48:152–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hollinghurst J, Fry R, Akbari Aet al. . External validation of the electronic frailty index using the population of Wales within the secure anonymised information linkage databank. Age Ageing 2019;48:922–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DataLoch . About the Data. https://dataloch.org/data/about-the-data(accessed 12th July 2024).

- 17. Nedkoff L, Lopez D, Hung Jet al. . Validation of ICD-10-AM coding for myocardial infarction subtype in hospitalisation data. Heart Lung Circ 2022;31:849–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glasheen WP, Cordier T, Gumpina Ret al. . Charlson comorbidity index: ICD-9 update and ICD-10 translation. Am Health Drug Benefits 2019;12:188–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuan V, Denaxas S, Gonzalez-Izquierdo Aet al. . A chronological map of 308 physical and mental health conditions from 4 million individuals in the English national health service. Lancet Digit Health 2019;1:e63–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DLet al. . Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation 2011;123:2736–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation 2016;133:601–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McNamara RL, Kennedy KF, Cohen DJet al. . Predicting In-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:626–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Wilkins Eet al. . Trends in the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK. Heart 2016;102:1945–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Temporelli Pet al. . Trends in acute myocardial infarction mortality in the European Union, 2012–2020. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2023;30:1758–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ekerstad N, Pettersson S, Alexander Ket al. . Frailty as an instrument for evaluation of elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a follow-up after more than 5 years. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;25:1813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graham MM, Galbraith PD, O'Neill Det al. . Frailty and outcome in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Can J Cardiol 2013;29:1610–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanchis J, Bonanad C, Ruiz Vet al. . Frailty and other geriatric conditions for risk stratification of older patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J 2014;168:784–791.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dou Q, Wang W, Wang Het al. . Prognostic value of frailty in elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr 2019;19:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Purser JL, Kuchibhatla MN, Fillenbaum GGet al. . Identifying frailty in hospitalized older adults with significant coronary artery disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1674–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Newman AB, Gottdiener JS, McBurnie MAet al. . Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M158–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Veronese N, Cereda E, Stubbs Bet al. . Risk of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in frail and pre-frail older adults: results from a meta-analysis and exploratory meta-regression analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2017;35:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Udell JA, Lu D, Bagai Aet al. . Preexisting frailty and outcomes in older patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2022;249:34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel A, Goodman SG, Yan ATet al. . Frailty and outcomes after myocardial infarction: insights from the CONCORDANCE registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e009859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lowry MTH, Doudesis D, Wereski Ret al. . Influence of age on the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2022;146:1135–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steg PG, López-Sendón J, Lopez de Sa Eet al. . External validity of clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee PY, Alexander KP, Hammill BGet al. . Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2001;286:708–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CPet al. . Acute coronary Care in the Elderly, part I. Circulation 2007;115:2549–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sinclair H, Kunadian V. Coronary revascularisation in older patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Heart 2016;102:416–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tahhan AS, Vaduganathan M, Greene SJet al. . Enrollment of older patients, women, and racial/ethnic minority groups in contemporary acute coronary syndrome clinical trials: a systematic review. JAMA Cardiol 2020;5:714–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tan YY, Papez V, Chang WHet al. . Comparing clinical trial population representativeness to real-world populations: an external validity analysis encompassing 43 895 trials and 5 685 738 individuals across 989 unique drugs and 286 conditions in England. Lancet Healthy Longev 2022;3:e674–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chung K, Wilkinson C, Veerasamy Met al. . Frailty scores and their utility in older patients with cardiovascular disease. Interv Cardiol 2021;16:e05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lewis ET, Williamson M, Lewis LPet al. . The feasibility of deriving the electronic frailty index from Australian general practice records. Clin Interv Aging 2022;17:1589–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stow D, Matthews FE, Barclay Set al. . Evaluating frailty scores to predict mortality in older adults using data from population based electronic health records: case control study. Age Ageing 2018;47:564–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sangen NMR, Azzahhafi J, Chan Pin Yin DRPPet al. . External validation of the GRACE risk score and the risk–treatment paradox in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Open Heart 2022;9:e001984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hung J, Roos A, Kadesjö Eet al. . Performance of the GRACE 2.0 score in patients with type 1 and type 2 myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2021;42:2552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Anand A, Cudmore S, Robertson Set al. . Frailty assessment and risk prediction by GRACE score in older patients with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Geriatr 2020;20:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. White HD, Westerhout CM, Alexander KPet al. . Frailty is associated with worse outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: insights from the TaRgeted platelet inhibition to cLarify the optimal strateGy to medicallY manage acute coronary syndromes (TRILOGY ACS) trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:231–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Batty J, Qiu W, Gu Set al. . One-year clinical outcomes in older patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome undergoing coronary angiography: an analysis of the ICON1 study. Int J Cardiol 2019;274:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Damluji AA, Forman DE, Wang TYet al. . Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome in the older adult population: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023;147:e32–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burns EM, Rigby E, Mamidanna Ret al. . Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health 2011;34:138–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.