Abstract

Background

Drug resistance testing aids in appropriate antiretroviral therapy selection to improve treatment success but may not be readily available. We evaluated the impact of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine (DTG/3TC) using pooled data from the TANGO and SALSA trials in adults who were virologically suppressed with or without historical resistance results at screening.

Methods

Adults who were virologically suppressed (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL for >6 months) with no prior virologic failure were randomized to switch to DTG/3TC (TANGO, n = 369; SALSA, n = 246) or continue their current antiretroviral regimen (CAR; TANGO, n = 372; SALSA, n = 247). Week 48 HIV-1 RNA ≥50 and <50 copies/mL (Snapshot algorithm, Food and Drug Administration; intention-to-treat exposed), CD4+ cell count, and safety were analyzed by availability of historical resistance results.

Results

Overall, 294 of 615 (48%) participants in the DTG/3TC group and 277 of 619 (45%) participants in the CAR group had no historical resistance results at screening. At week 48, proportions with Snapshot HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL were low (≤1.1%) and similar across treatment groups and by historical resistance results availability. High proportions (91%–95%) maintained virologic suppression through week 48, regardless of results availability. Across both subgroups of results availability, greater increases in CD4+ cell count from baseline to week 48 occurred with DTG/3TC vs CAR. No participants taking DTG/3TC had confirmed virologic withdrawal, regardless of historical resistance results availability. One participant undergoing CAR without historical resistance results had confirmed virologic withdrawal; no resistance was detected. Overall, DTG/3TC was well tolerated; few adverse events led to withdrawal.

Conclusions

Findings support DTG/3TC as a robust switch option for adults who are virologically suppressed with HIV-1 and no prior virologic failure, regardless of historical resistance results availability.

Clinical trial registration

TANGO: NCT03446573, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03446573. SALSA: NCT04021290, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04021290

Keywords: DTG/3TC, historical resistance, resistance mutations, suppressed switch, virologically suppressed

Observations from this pooled analysis demonstrate the high efficacy and barrier to resistance, as well as the good safety profile, of dolutegravir/lamivudine in individuals who are virologically suppressed with HIV-1 in stable switch settings, with similar treatment outcomes achieved in participants with and without historical resistance results.

Based on results from the GEMINI-1/GEMINI-2, TANGO, and SALSA phase 3 clinical trials, the 2-drug regimen dolutegravir/lamivudine (DTG/3TC) is recommended by international guidelines as an initial antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen and as a switch option in people with HIV-1 who are virologically suppressed [1]. GEMINI-1/GEMINI-2 demonstrated the noninferior efficacy of DTG + 3TC to the 3-drug regimen DTG + tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) through week 144 in participants who were ART naive, while SALSA and TANGO showed the noninferiority of switching to DTG/3TC vs continuing 3- or 4-drug regimens through week 48 (SALSA; various ART regimens) and week 144 (TANGO; tenofovir alafenamide [TAF]–based regimens) in participants who were virologically suppressed with no prior virologic failure. All studies also reported the good safety profile and high barrier to resistance of DTG/3TC, although individuals were ineligible to participate if they had any evidence of major mutations associated with resistance to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) or DTG [2–6].

Drug resistance testing of plasma HIV-1 RNA is recommended in US and European guidelines to determine the potential presence of preexisting resistance to ART before treatment initiation and at the time of virologic failure [7, 8]. These tests may not be readily accessible, or historical HIV resistance results may not be available. Among individuals who were naive to ART with no baseline resistance results, the efficacy of DTG/3TC was shown to be noninferior to DTG-based 3-drug regimens at 24 weeks in the phase 4 D2ARLING study [9]. However, those who are stably suppressed have a plasma viral load below the threshold of resistance testing for routine clinical assays, and many people requiring or requesting a switch in their ART regimen might not have a complete medical history. While preexisting resistance mutations to DTG and 3TC are rare in treatment-naive populations [10–12], the M184V/I mutation conferring high-level resistance to 3TC and FTC is commonly observed after treatment failure [13]. Although DTG/3TC is not indicated for individuals with M184V/I, it is important to understand the impact of this mutation on the efficacy and safety of 2-drug regimens containing 3TC or FTC in those who do not have historical HIV resistance data available.

To increase the precision of estimates in subgroups of scientific importance, data from the TANGO and SALSA trials were pooled. While historical plasma viral RNA resistance genotype was not required for enrollment, it was utilized for inclusion or exclusion when available. Here, we present pooled efficacy and safety analyses from the TANGO and SALSA trials in adults who were virologically suppressed with and without historical resistance results at screening to examine whether the absence of historical resistance results affects the efficacy and safety of DTG/3TC after ART regimen switch.

METHODS

Study Design

Detailed methodology has been published for both studies (TANGO: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03446573; SALSA: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT04021290) [4, 6, 14]. In brief, adults with HIV-1 who were virologically suppressed were randomized to switch to a once-daily fixed-dose combination of DTG (50 mg)/3TC (300 mg) or continue their current antiretroviral regimen (CAR). In the TANGO study, the current regimen was TAF/FTC + protease inhibitor, integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). In the SALSA study, the current regimen was 2 NRTIs + protease inhibitor, INSTI, or NNRTI. Inclusion criteria included the following: ≥2 documented HIV-1 RNA measurements <50 copies/mL for >6 months before screening, no hepatitis B virus infection or need for hepatitis C virus therapy, and no prior virologic failure. Exclusion criteria included the following: any evidence of major NRTI resistance–associated mutation or any INSTI resistance–associated mutation in any historical genotype assay results, if available; plasma HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL within 6 months of screening; ≥2 measurements ≥50 copies/mL or any measurement >200 copies/mL within 6 and 12 months of screening; or prior regimen switch for virologic failure (HIV-1 RNA ≥400 copies/mL).

Study data collection dates for TANGO were 18 January 2018 (first participant, first visit) to 20 May 2019 (last participant, last visit); the data cutoff date for the 48-week analysis was 19 June 2019. Study data collection dates for SALSA were 11 November 2019 (first participant, first visit) to 23 April 2021 (last participant, last visit); the data cutoff date for the 48-week analysis was 21 May 2021.

Patient Consent Statement

Both studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from ethics committees at the investigational sites. All participants provided written informed consent before study initiation.

Procedures

Detailed procedures have been published [4, 6, 14]. Briefly, eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to switch to a once-daily fixed-dose combination of DTG/3TC or continue CAR. No regimen modifications were allowed, except switching between ritonavir and cobicistat (TANGO, SALSA) or 3TC and FTC (SALSA) in the CAR group. Study visits were planned at baseline (day 1) and weeks 4, 8 (TANGO only), 12, 24, 36, and 48. Plasma for HIV-1 RNA quantification was collected, and safety outcomes were assessed at each visit. Post hoc HIV-1 proviral DNA genotyping was conducted retrospectively on whole blood samples to evaluate baseline preexisting resistance using the GenoSure Archive assay (Monogram Biosciences). These resistance mutations were reported via a mutation prevalence cutoff of 10% for TANGO and 15% for SALSA.

Outcomes

Data were analyzed by subgroups of participants with and without historical resistance results at screening. Demographics and baseline characteristics were collected for each subgroup. In the subgroup of participants with historical resistance results at screening, the most frequent major resistance-associated mutations at baseline were identified. In TANGO and SALSA, the primary end point was the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL at week 48 according to the US Food and Drug Administration Snapshot algorithm in the intention-to-treat–exposed (ITT-E) population. Key secondary end points were as follows: the proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL (Snapshot, ITT-E); change from baseline in CD4+ cell count and CD4+/CD8+ ratio; and incidence of observed genotypic/phenotypic resistance in participants meeting criteria for confirmed virologic withdrawal (CVW), defined as HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL, followed by a second consecutive on-treatment HIV-1 RNA ≥200 copies/mL. Safety assessments included incidence and severity of adverse events (AEs) and discontinuations due to AEs.

Statistical Analysis

A pooled analysis of results from the phase 3 TANGO and SALSA clinical trials was performed. All randomized participants who received ≥1 dose of study treatment were included in the ITT-E population, which was used for efficacy and safety analyses.

Proportions of participants with HIV-1 RNA ≥50 and <50 copies/mL (Snapshot) at week 48 were analyzed by a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test adjusting for baseline third agent class. Mixed models repeated measures analysis was used for the adjusted mean change from baseline in CD4+ cell count and CD4+/CD8+ ratio, adjusting for the following:

treatment, visit, age, sex, and race;

baseline CD4+ cell count, body mass index, third agent, and resistance results;

interactions for (1) treatment × visit, (2) baseline value × visit, (3) visit × baseline resistance results, (4) treatment × baseline resistance results, and (5) treatment × visit × baseline resistance results; and

study (combined analysis only), with visit as the repeated factor.

Baseline CD4+/CD8+ ratio was an additional adjustment term for CD4+/CD8+ ratio. Incidence and severity of AEs were summarized descriptively.

RESULTS

Participants

In TANGO, 919 participants were screened, with 743 randomized to switch to DTG/3TC (n = 371) or continue their TAF-based regimen (n = 372); 2 participants randomized to DTG/3TC did not receive study treatment and were excluded from the ITT-E population. In SALSA, 593 participants were screened, and 246 were randomized to switch to DTG/3TC and 247 to continue CAR. Screening failure (TANGO, n = 176; SALSA, n = 100) was primarily due to inclusion/exclusion criteria (TANGO, n = 142; SALSA, n = 70), including variation in ART regimens before study enrollment, lack of viral load documentation, and presence of major NRTI or INSTI resistance mutations (TANGO, 9/919 [<1%]; SALSA, 2/593 [<1%]). Additionally, in SALSA, 2 participants who were randomized to switch to DTG/3TC and 2 who were randomized to continue CAR were excluded from the per-protocol population after major NRTI or INSTI resistance mutations were identified; these participants were not excluded from the ITT-E population and are included in this analysis. This pooled analysis comprised 1234 participants: 615 in the DTG/3TC group and 619 in the CAR group.

In the overall ITT-E population, 20% (250/1234) of participants identified as female and 71% (878/1234) as White, and the median age was 42 years (range, 18–83; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics by Availability of Historical Resistance Results at Screening and Overall: TANGO and SALSA Pooled ITT-E Population

| No Historical Resistance Results at Screening | Historical Resistance Results at Screening | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | DTG/3TC (n = 294) | CAR (n = 277) | DTG/3TC (n = 321) | CAR (n = 342) | DTG/3TC (n = 615) | CAR (n = 619) |

| Age, y | 42 (20–74) | 43 (20–83) | 42 (22–74) | 41 (18–73) | 42 (20–74) | 42 (18–83) |

| ≥50 y | 80 (27) | 85 (31) | 97 (30) | 102 (30) | 177 (29) | 187 (30) |

| Sex: female | 82 (28) | 76 (27) | 51 (16) | 41 (12) | 133 (22) | 117 (19) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 201 (68) | 178 (64) | 244 (76) | 255 (75) | 445 (72) | 433 (70) |

| Black | 45 (15) | 48 (17) | 51 (16) | 58 (17) | 96 (16) | 106 (17) |

| Asian | 30 (10) | 34 (12) | 14 (4) | 18 (5) | 44 (7) | 52 (8) |

| Other racesa | 18 (6) | 17 (6) | 12 (4) | 11 (3) | 30 (5) | 28 (5) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 75 (26) | 71 (26) | 59 (18) | 50 (15) | 134 (22) | 121 (20) |

| Not Hispanic/Latinx | 219 (74) | 206 (74) | 262 (82) | 292 (85) | 481 (78) | 498 (80) |

| CD4+ cell count, cells/mm3 | 685 (154–2089) | 675 (94–1954) | 666 (133–1678) | 686 (122–1810) | 680 (133–2089) | 684 (94–1954) |

| <350 | 28 (10) | 23 (8) | 28 (9) | 24 (7) | 56 (9) | 47 (8) |

| ≥350 | 266 (90) | 254 (92) | 292 (91) | 318 (93) | 558 (91) | 572 (92) |

| CD4+/CD8+ ratio | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 0.9 (0–4) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–4) | 1.0 (0–3) |

| Duration of ART before day 1, mo | 44 (7–240) | 47 (7–253) | 38 (4–233) | 44 (7–188) | 41 (4–240) | 45 (7–253) |

| Baseline third agent classb | ||||||

| INSTI | 154 (52) | 148 (53) | 233 (73) | 246 (72) | 387 (63) | 394 (64) |

| NNRTI | 113 (38) | 112 (40) | 61 (19) | 60 (18) | 174 (28) | 172 (28) |

| Protease inhibitor | 27 (9) | 17 (6) | 27 (8) | 36 (11) | 54 (9) | 53 (9) |

Data are presented as median (range) or No. (%).

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral regimen; CAR, current antiretroviral regimen; DTG/3TC, dolutegravir/lamivudine; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; ITT-E, intention-to-treat exposed; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

aIncludes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, mixed White race, and individuals of multiple races.

bDue to rounding, total percentage might not equal 100%.

Overall, 294 of 615 (48%) participants in the DTG/3TC group and 277 of 619 (45%) in the CAR group had no historical resistance results available at screening. Among subsets of participants with archived resistance, the prevalence of major resistance-associated mutations was comparable between treatment groups in the TANGO (Supplementary Table 1) and SALSA (Supplementary Table 2) populations. Baseline demographics in participants with and without historical resistance results were similar and generally consistent with those of the overall population. In both treatment groups, the median time undergoing the baseline regimen was similar between participants with historical resistance results available (DTG/3TC, 38 months [range, 4–233]; CAR, 44 [7–188]) and those without (DTG/3TC, 44 months [range, 7–240]; CAR, 47 [7–253]). Regardless of historical resistance results availability at screening, treatment groups had a similar ART history at baseline, with INSTIs being the most commonly used third agent class in participants with availability (DTG/3TC, 73%; CAR, 72%) and without (DTG/3TC, 52%; CAR, 53%).

Efficacy

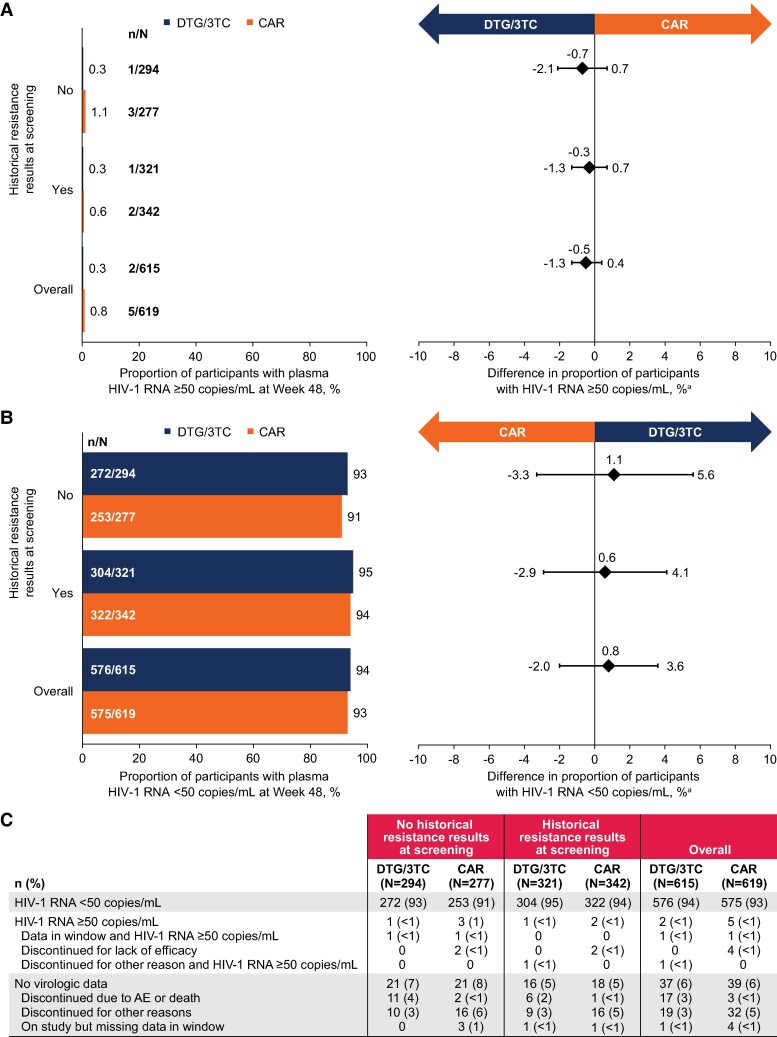

At week 48, proportions of participants with Snapshot HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL were low and similar across treatment groups and by availability of historical resistance results at screening (Figure 1A). Four participants with no results at screening had HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL (DTG/3TC, 1/294; CAR, 3/277; adjusted difference, −0.7%; 95% CI, −2.1% to .7%) vs 3 participants with results (DTG/3TC, 1/321; CAR, 2/342; adjusted difference, −0.3%; 95% CI, −1.3% to .7%). The proportion of participants maintaining HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/mL (Snapshot, ITT-E population) was high in both treatment groups, regardless of availability of historical resistance results (Figure 1B). In participants without historical resistance results available, 93% (272/294) in the DTG/3TC group and 91% (253/277) in the CAR group maintained virologic suppression (adjusted difference, 1.1%; 95% CI, −3.3% to 5.6%). Similarly, 95% (304/321) and 94% (322/342) of participants with historical resistance results in the DTG/3TC and CAR groups, respectively, maintained virologic suppression (adjusted difference, 0.6%; 95% CI, −2.9% to 4.1%).

Figure 1.

Proportions of participants with Snapshot HIV-1 RNA: A, ≥50 copies/mL; B, <50 copies/mL. C, Snapshot analysis by availability of historical resistance results at screening and overall: TANGO and SALSA pooled ITT-E population. aAdjusted difference (95% CI) for each population (DTG/3TC − CAR). AE, adverse event; CAR, current antiretroviral regimen; DTG/3TC, dolutegravir/lamivudine; ITT-E, intention-to-treat exposed.

Among participants without historical resistance results at screening, the DTG/3TC group had an increase in CD4+ cell count from baseline to week 48 (adjusted mean change [SE], 21.2 [10.5] cells/mm3), whereas the CAR group experienced a decrease from baseline of −17.3 (10.3) cells/mm3 (Table 2). In participants with historical resistance results at screening, the adjusted mean change (SE) in CD4+ cell count from baseline to week 48 was comparable between the DTG/3TC and CAR groups (23.5 [10.0] vs 10.2 [9.2] cells/mm3). Adjusted mean change (SE) in CD4+/CD8+ ratio from baseline to week 48 was similar between the DTG/3TC and CAR groups among participants without historical resistance results (DTG/3TC, 0.03 [0.01]; CAR, 0.04 [0.01]) and among those with historical resistance results (DTG/3TC, 0.04 [0.01]; CAR, 0.06 [0.01]).

Table 2.

Adjusted Mean Change From Baseline to Week 48 in CD4+ Cell Count and CD4+/CD8+ Ratio by Availability of Historical Resistance Results at Screening and Overall: TANGO and SALSA Pooled ITT-E Population

| No Historical Resistance Results at Screening | Historical Resistance Results at Screening | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | DTG/3TC (n = 294) | CAR (n = 277) | DTG/3TC (n = 321) | CAR (n = 342) | DTG/3TC (n = 615) | CAR (n = 619) |

| CD4+ cell count, cells/mm3 | ||||||

| Baseline, median (range) | 685 (154–2089) | 675 (94–1954) | 666 (133–1678) | 686 (122–1810) | 680 (133–2089) | 684 (94–1954) |

| Adjusted mean (SE) change from baseline at week 48 | 21.2 (10.5) | −17.3 (10.3) | 23.5 (10.0) | 10.2 (9.2) | 22.4 (7.2) | −2.0 (6.9) |

| Adjusted difference (95% CI) | 38.5 (9.7, 67.2) | 13.3 (−13.3, 39.8) | 24.4 (4.9, 43.9) | |||

| CD4+/CD8+ ratio | ||||||

| Baseline ratio, median (range) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 0.9 (0–4) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–4) | 1.0 (0–3) |

| Adjusted mean (SE) change from baseline at week 48 | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) |

| Adjusted difference (95% CI) | −0.01 (−.04, .03) | −0.02 (−.05, .01) | −0.02 (−.04, .01) | |||

Adjustment terms included treatment, visit, age, sex, race, baseline value, baseline body mass index, baseline third agent class, treatment × visit interaction, baseline value × visit interaction, and study, with visit as the repeated factor. Subgroup analyses by availability of historical resistance results at screening were also adjusted for baseline resistance results and the following interactions: visit × baseline resistance results, treatment × baseline resistance results, and treatment × visit × baseline resistance results. For CD4+/CD8+ ratio, baseline CD4+ cell count was an additional adjustment term.

Abbreviations: CAR, current antiretroviral regimen; DTG/3TC, dolutegravir/lamivudine; ITT-E, intention-to-treat exposed.

No participants receiving DTG/3TC, regardless of historical resistance results availability, met criteria for CVW. One participant in the CAR group (undergoing a regimen of cobicistat-boosted elvitegravir/TAF/FTC) without historical resistance results at screening met CVW criteria, and no resistance was detected at failure.

Safety

Safety results were similar in participants with and without historical resistance results available at screening and consistent with the overall analysis (Table 3). Through week 48, the overall incidence of any AEs was comparable between the DTG/3TC and CAR groups (without historical resistance results, 76% [223/294] vs 71% [196/276], respectively; with historical resistance results, 79% [252/321] vs 78% [268/342]; overall, 77% [475/615] vs 75% [464/618]), with low incidences of AEs leading to withdrawal and serious AEs. In the overall population, the more frequent drug-related AEs with DTG/3TC vs CAR primarily occurred within the first 24 weeks (13% [79/615] vs 2% [15/618]) and were comparable after week 24 (3% [16/615] vs <1% [6/618]).

Table 3.

AEs Through Week 48 by Availability of Historical Resistance Results at Screening and Overall: TANGO and SALSA Pooled Safety Population

| No Historical Resistance Results at Screening | Historical Resistance Results at Screening | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | DTG/3TC (n = 294) | CAR (n = 276) | DTG/3TC (n = 321) | CAR (n = 342) | DTG/3TC (n = 615) | CAR (n = 618) |

| Any AE | 223 (76) | 196 (71) | 252 (79) | 268 (78) | 475 (77) | 464 (75) |

| AEs leading to withdrawal | 11 (4) | 3 (1) | 7 (2) | 2 (<1) | 18 (3) | 5 (<1) |

| Drug-related AEs | 49 (17) | 15 (5) | 44 (14) | 6 (2) | 93 (15) | 21 (3) |

| Grade 2–5 AEs | 126 (43) | 115 (42) | 155 (48) | 188 (55) | 281 (46) | 303 (49) |

| Any serious AE | 13 (4) | 15 (5) | 15 (5) | 17 (5) | 28 (5) | 32 (5) |

Data are presented as No. (%). In TANGO, 1 participant was taking a TDF-based regimen and was thus excluded from the safety population.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CAR, current antiretroviral regimen; DTG/3TC, dolutegravir/lamivudine; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

The proportion of participants with drug-related AEs was higher in the DTG/3TC group as compared with the CAR group, regardless of availability of historical resistance results (without historical resistance results, 17% [49/294] vs 5% [15/276], respectively; with historical resistance results: 14% [44/321] vs 2% [6/342]). Proportions of AEs leading to withdrawal were low in both treatment groups regardless of resistance results as well (DTG/3TC vs CAR: without historical resistance results, 4% [11/294] vs 1% [3/276]; with historical resistance results, 2% [7/321] vs <1% [2/342]). The frequency of serious AEs was similar between treatment groups (DTG/3TC vs CAR: without historical resistance results, 4% [13/294] vs 5% [15/276]; with historical resistance results, 5% [15/321] vs 5% [17/342]), as was the frequency of grade 2–5 AEs (without historical resistance results, 43% [126/294] vs 42% [115/276]; with historical resistance results, 48% [155/321] vs 55% [188/342]).

DISCUSSION

Week 48 efficacy outcomes from the pooled analysis of TANGO and SALSA demonstrated low rates of HIV-1 RNA ≥50 copies/mL, high proportions of virologic suppression, no CVWs, and no resistance development in the DTG/3TC group regardless of historical HIV resistance results availability at screening. Overall, DTG/3TC was well tolerated; proportions of AEs in participants with and without historical resistance results at screening were similar. These results support the efficacy and safety of switching to DTG/3TC in people with HIV-1 who are virologically suppressed and have no prior virologic failure. Additionally, results are reassuring for the efficacy of switching to DTG/3TC in the context of a lack of historical resistance information—for example, in settings where genotypic testing is unavailable or in people without historical resistance results.

In the TANGO and SALSA trials, 48% (294/615) of participants who switched to DTG/3TC did not have historical resistance results available at screening. This finding is consistent with real-world observational studies in Italy and Spain of people with HIV-1 who were virologically suppressed and switched to DTG/3TC; both studies reported that baseline genotypic resistance results were not available for 49% (331/669 and 88/178, respectively) of individuals [15, 16]. However, neither study reported virologic outcomes in those with and without available genotypic resistance results, as we have done in this pooled analysis of TANGO and SALSA; moreover, to our knowledge, a similar analysis has not been conducted in other real-world studies of people with HIV-1 who were ART experienced and switched to DTG/3TC.

These outcomes are consistent with observations from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis that consisted of 5 real-world evidence–based studies and 5 interventional trials, including TANGO and SALSA, of individuals who were ART experienced and had switched to DTG/3TC while having M184V/I mutations previously detected by historical RNA or archived proviral DNA [17]. Overall, the systematic literature review showed a low prevalence of M184V/I before the switch to DTG/3TC in the evidence-based studies (11% [264/2428]) and low proportions of virologic failure postswitch among those with historical M184V/I in both the evidence-based studies (week 24, 1.43% [3/210]; week 48, 3.45% [9/261]; week 96, 3.81% [8/210]) and the interventional trials (week 24, 0% [0/42]; week 48, 0% [0/97]; week 96, 0% [0/38]). Furthermore, no treatment-emergent resistance mutations were reported in any of the real-world studies or interventional trials analyzed. Altogether, these data support favorable outcomes with DTG/3TC in individuals with HIV-1, including cases where preexisting M184V/I mutations were unknown.

Although TANGO and SALSA excluded participants with major NRTI or INSTI resistance mutations at screening or documented prior virologic failure, nearly half of participants did not have historical resistance results available, and virologic suppression rates were high and similar to those with available historical resistance results. These results are in alignment with findings from post hoc analyses based on archived proviral DNA [18]. At week 48 in the SALSA study, 192 (78%) participants in the DTG/3TC group and 185 (75%) in the CAR group were tested for proviral DNA resistance [18]. Frequency of any overall major class resistance was similar across treatment groups (DTG/3TC, 28%; CAR, 22%), with M184V/I mutations similarly distributed across groups (3% each). At week 144 in TANGO, 330 of 366 (90%) participants in the DTG/3TC group and 324 of 368 (88%) in the TAF-based regimen group had proviral DNA genotypes available. The frequency of any overall major class resistance-associated mutations was similar (DTG/3TC, 25%; CAR, 28%), with the frequency of M184V/I mutations comparable between groups (∼1%) [14]. These results suggest that switching to DTG/3TC leads to maintenance of virologic suppression in high proportions of individuals without historical resistance results at screening, as well as those in whom archived resistance was detected with proviral DNA testing. Although proviral DNA resistance testing can show the presence of archived resistance mutations in low-level or suppressed viremia, it is not conclusive in showing the absence of preexisting resistance. Additionally, proviral DNA detection based on next-generation sequencing technology may overestimate APOBEC hypermutation–mediated variants (apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide), such as M184I, depending on reporting thresholds [19–21]. Therefore, while proviral DNA testing may be useful when historical plasma RNA resistance results are unavailable, its clinical relevance remains uncertain, and interpretations should be made with these caveats in mind [8].

This study had some limitations. The TANGO and SALSA studies excluded participants with resistance or prior virologic failure, although availability of historical resistance results was not required to assess eligibility. Post hoc proviral DNA testing identified a small sample of participants with archived M184V/I resistance in both studies [14, 18], including some participants with available historical resistance results at screening. This discrepancy in M184V/I detection between historical RNA resistance testing and proviral DNA resistance testing illustrates the discordance that can be observed between the methods [22]. While subgroup analyses have the potential to enhance our understanding of clinical trial outcomes, they bring inherent challenges such as reduced statistical power and an increased risk of type I error; hence, careful interpretation of these results is essential, particularly in the context of consistency with existing literature.

CONCLUSIONS

Observations from this pooled analysis further demonstrate not only the high efficacy and barrier to resistance but also the safety of DTG/3TC for individuals who are virologically suppressed with HIV-1 in stable switch settings, reinforcing the use of DTG/3TC as a robust switch option for adults with virologic suppression and no prior virologic failure. Similar treatment outcomes were achieved in participants with and without historical resistance results. This finding indicates that DTG/3TC is a viable switch option for those who are virologically suppressed, including in circumstances where historical resistance results are unavailable or preexisting archived M184V/I is unknown.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Stefan Scholten, Praxis Hohenstaufenring, Cologne, Germany.

Pedro Cahn, Fundación Huésped, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Joaquín Portilla, Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Alicante, Spain.

Fiona Bisshop, Holdsworth House Medical Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.

Sally Hodder, West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA.

Peter Ruane, Ruane Clinical Research, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Richard Kaplan, Desmond Tutu Health Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa.

Brian R Wynne, ViiV Healthcare, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Choy Y Man, ViiV Healthcare, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Richard Grove, GSK, Brentford, UK.

Ruolan Wang, ViiV Healthcare, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

Bryn Jones, ViiV Healthcare, Brentford, UK.

Mounir Ait-Khaled, ViiV Healthcare, Brentford, UK.

Michelle Kisare, ViiV Healthcare, Brentford, UK.

Chinyere Okoli, ViiV Healthcare, Brentford, UK.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the study participants and their families and caregivers; the investigators and site staff who participated in the TANGO and SALSA studies; and the ViiV Healthcare, GSK, and PPD study team members. Editorial assistance was provided under the direction of the authors by Deborah Lew, PhD, and Jennifer Rossi, MA, ELS, MedThink SciCom, and was funded by ViiV Healthcare.

Author contributions . B. R. W., R. G., M. A.-K., and C. O. contributed to the conception and design of the study. S. S., P. C., J. P., F. B., S. H., P. R., R. K., and R. W. contributed to the acquisition of data. R. G. and R. W. contributed to the analysis of data. S. S., P. C., J. P., F. B., S. H., P. R., R. K., B. R. W., C. Y. M., R. G., R. W., B. J., M. A.-K., M. K., and C. O. contributed to the interpretation of data. B. R. W., R. G., R. W., B. J., M. A.-K., M. K., and C. O. contributed to drafting the manuscript. All authors contributed to critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript for publication.

Patient consent statement . Both studies were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice and followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was obtained from ethics committees at the investigational sites. All participants provided written informed consent before study initiation.

Data availability. Anonymized individual participant data and study documents can be requested for further research from www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Financial support. This work was supported by ViiV Healthcare.

References

- 1. Gandhi RT, Bedimo R, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA panel. JAMA 2023; 329:63–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cahn P, Sierra Madero J, Arribas JR, et al. Dolutegravir plus lamivudine versus dolutegravir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2): week 48 results from two multicentre, double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2019; 393:143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cahn P, Sierra Madero J, Arribas JR, et al. Three-year durable efficacy of dolutegravir plus lamivudine in antiretroviral therapy-naive adults with HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2022; 36:39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llibre JM, Brites C, Cheng C-Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to the 2-drug regimen dolutegravir/lamivudine versus continuing a 3- or 4-drug regimen for maintaining virologic suppression in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1): week 48 results from the phase 3, noninferiority SALSA randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:720–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osiyemi O, De Wit S, Ajana F, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine versus continuing a tenofovir alafenamide-based 3- or 4-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results through week 144 from the phase 3, noninferiority TANGO randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:975–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Wyk J, Ajana F, Bisshop F, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine fixed-dose 2-drug regimen vs continuing a tenofovir alafenamide-based 3- or 4-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: phase 3, randomized, noninferiority TANGO study. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1920–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. European AIDS Clinical Society . EACS guidelines version 12.0. European AIDS Clinical Society. October 2023. Available at: https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-12.0.pdf. Accessed 15 December 2023.

- 8. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents . Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. December 2023. Available at: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-arv/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf. Accessed 15 December 2023.

- 9. Cordova E, Hernandez Rendon J, Mingrone V, et al. Efficacy of dolutegravir plus lamivudine in treatment-naive people living with HIV without baseline drug-resistance testing: week 24 results of the randomized D2ARLING study. Presented at: 12th IAS Conference on HIV Science; 23–26 July 2023; Brisbane, Australia.

- 10. Stekler JD, McKernan J, Milne R, et al. Lack of resistance to integrase inhibitors among antiretroviral-naive subjects with primary HIV-1 infection, 2007–2013. Antivir Ther 2015; 20:77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vannappagari V, Ragone L, Henegar C, et al. Prevalence of pretreatment and acquired HIV-1 mutations associated with resistance to lamivudine or rilpivirine: a systematic review. Antivir Ther 2019; 24:393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aghokeng AF, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Huynh THK, et al. Prevalence of pretreatment HIV resistance to integrase inhibitors in West African and Southeast Asian countries. J Antimicrob Chemother 2024; 79:1164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fokam J, Inzaule S, Colizzi V, Perno C-F, Kaseya J, Ndembi N. HIV drug resistance to integrase inhibitors in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med 2024; 30:618–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang R, Wright J, Saggu P, et al. Assessing the virologic impact of archived resistance in the dolutegravir/lamivudine 2-drug regimen HIV-1 switch study TANGO through week 144. Viruses 2023; 15:1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borghetti A, Giacomelli A, Borghi V, et al. Nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor resistance mutations predict virological failure in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients during lamivudine plus dolutegravir maintenance therapy in clinical practice. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8:ofab103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Cortés LL, Gutiérrez A, et al. DOLAMA study: effectiveness, safety and pharmacoeconomic analysis of dual therapy with dolutegravir and lamivudine in virologically suppressed HIV-1 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98:e16813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kabra M, Barber TJ, Allavena C, et al. Virologic response to dolutegravir plus lamivudine in people with suppressed human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and historical M184V/I: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 10:ofad526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Underwood M, Osiyemi O, Rubio R, et al. Archived resistance and response to <40 c/mL and TND–DTG/3TC FDC at week 48 in SALSA. Presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 12–16 February 2022; virtual.

- 19. Fourati S, Malet I, Lambert S, et al. E138k and M184I mutations in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase coemerge as a result of APOBEC3 editing in the absence of drug exposure. AIDS 2012; 26:1619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geretti AM, Blanco JL, Marcelin AG, et al. HIV DNA sequencing to detect archived antiretroviral drug resistance. Infect Dis Ther 2022; 11:1793–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chu C, Armenia D, Walworth C, Santoro MM, Shafer RW. Genotypic resistance testing of HIV-1 DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Microbiol Rev 2022; 35:e0005222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Günthard HF, Calvez V, Paredes R, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance: 2018 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA panel. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:177–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.