Abstract

Background

Mesenteric panniculitis (MP) is an uncommon non-neoplastic idiopathic inflammation of adipose tissue, mainly affecting the mesentery of the small intestine, with its etiology remaining largely speculative. The difference in prevalence of MP among females and males varies across multiple studies. In most cases, MP is asymptomatic; however, patients can present with nonspecific abdominal symptoms or can mimic underlying gastrointestinal and abdominal diseases. The diagnosis is suggested by computed tomography and is usually confirmed by surgical biopsies if necessary. Treatment is generally supportive and based on a few selected drugs, namely, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids. Surgery is reserved when the diagnosis is unclear, when malignancy is suspected or in the case of severe presentation such as mass effect, bowel obstruction, or ischemic changes.

Summary

MP is a rare inflammatory condition of the mesentery often asymptomatic but can cause nonspecific abdominal symptoms. Diagnosis relies on computed tomography imaging, with treatment mainly supportive, utilizing medications like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or corticosteroids, while surgery is reserved for severe cases or diagnostic uncertainty.

Key Messages

MP causes abdominal pain, and it is mainly diagnosed with CT scan.

Keywords: Mesenteric panniculitis, Mesentery, Computed tomography

Introduction

First described during abdominal surgery by Jura in 1924 [1], mesenteric panniculitis (MP) is a relatively rare pathology characterized by a spectrum of idiopathic acute and chronic inflammation of adipose tissue, mainly affecting the mesentery of the small intestine and to a lesser extent the mesocolon [2]. It rarely involves the omentum, the retroperitoneal and pelvic fat [3]. MP has several nomenclatures: retractile mesenteritis, mesenteric lipodystrophy, sclerosing mesenteritis, Weber-Christian disease, mesenteric lipogranuloma, liposclerotic mesenteritis, idiopathic mesenteric fibrosis, and misty mesentery [4, 5]. No criteria were well established, but acute disease is defined as presentation with symptoms occurring for less than 30 days, while chronic disease is defined by symptoms for more than 30 days. With advancements in abdominal imaging and ease of access to computerized tomography (CT), this rare condition is more frequently encountered, and most cases are noted incidentally and less relevant to the original indication for the CT scan. A prospective study, including 7,620 consecutive abdominal CT examination from Greece, showed a prevalence of 0.6% [6]. Another retrospective study from Turkey showed that among 19,869 CT scans, only 36 (0.18%) had MP [7]. The literature shows that the prevalence on abdominal imaging ranges from 0.18% up to 7.8% [6–8] and usually occurs after the fifth decade, peaking in the 6th and 7th decade of life [4]. The prevalence of MP among gender is variable with most articles showing a male predominance of (2–3:1) [9–12]. However, some articles showed that females are more commonly affected with MP [6]. There is no distinct association with race [13], although some articles have reported that affected patients are primarily Caucasian [2], but this could be because most studies have been conducted in White-predominant populations [14]. The course of the disease is usually benign, but sometimes MP may be the cause of bowel perforation, bowel obstruction, bowel ischemia, and renal failure due to ureteral stenosis and may constitute a potentially lethal disease requiring urgent medical or surgical treatment [4, 12, 15]. Mortality is not accurately reported; however, death from MP appears to be rare and mainly attributed to underlying malignancy [16]. The correct evaluation of the symptomatology, therefore, appears to be a fundamental step in the clinical and therapeutic framework of this disease to identify the most critical situations.

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Natural History

The pathogenic mechanism of MP seems to be a nonspecific response to a wide variety of stimuli. Although various causal factors have been identified, the precise etiology remains unknown and subject of debate. Several authors [3, 16, 17] have reported a series in which 33–57% of patients had a history of abdominal trauma or surgery. Furthermore, the disease is related to other factors, such as mesenteric thrombosis, mesenteric arteriopathy, drugs, thermal or chemical injuries, vasculitis, avitaminosis, autoimmune disease, retained suture material, pancreatitis, bile or urine leakage, hypersensitivity reactions, and even bacterial or viral infection [4, 18, 19] (Table 1). Many experts describe MP as an autoimmune disease since this condition is characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration on biopsy, is associated with increased inflammatory markers, and responds well to immunomodulatory treatment. MP is frequently associated with various idiopathic inflammatory conditions, including retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing cholangitis, and Riedel’s thyroiditis [20]. Coexistence with idiopathic fibrosclerotic disorders like retroperitoneal fibrosis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and sclerosing pancreatitis has also been documented [21]. Patients with MP commonly exhibit a strong familial predisposition to autoimmune conditions [22]. Other factors, such as gallstones, coronary disease, cirrhosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, peptic ulcer, or chylous ascites, have also been linked to this disease [23]. More recent studies have shown a strong relationship between tobacco consumption and panniculitis [19]. A newly published retrospective, matched case-control study reported a significant increase in dyslipidemia, obesity, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with MP compared to other hospitalized patients and to the general population implying the possible involvement of the metabolic syndrome in this disease [24]. In addition, significant increase in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue was found in a retrospective study comparing patients with MP to controls [25].

Table 1.

Lists the possible differential diagnosis of MP

| Infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, histoplasmosis) |

| Amyloidosis |

| Whipple’s disease |

| Lymphoma |

| Lymphosarcoma |

| Carcinoid tumors |

| Retroperitoneal sarcoma |

| Desmoid tumors/desmoplastic carcinoma/metastases |

| Peritoneal mesothelioma |

| Chronic inflammation due to foreign body |

| Reaction to adjacent cancer or chronic abscess |

MP has been associated with a number of malignancies (from 17% to 69% in several series) such as lung cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, colon cancer, renal cell cancer, multiple myeloma, gastric carcinoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, and carcinoid tumors [18, 19, 26–29]. Experts suggest that MP may manifest as a paraneoplastic syndrome, and its presence on imaging should prompt additional investigations to rule out a possible malignancy [30]. However, two meta-analyses and systemic reviews of previous cohorts by Halligan et al. [31] and Hussain et al. [32] concluded that the heterogeneity of the study designs could not determine an association between MP and lymphoproliferative disease or any specific malignancy.

The histological progression of the disease is in 3 stages [18, 33]. Stage one is mesenteric lipodystrophy, where foamy macrophages replace mesenteric fat. Acute inflammatory signs are minimal; clinically asymptomatic and prognosis is good. The second stage, termed MP, infiltrate made up of plasma cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes, foreign body giant cells, and foamy macrophages. Most common symptoms include pyrexia, abdominal pain, and malaise. The third stage is retractile mesenteritis, where collagen deposition, fibrosis, and inflammation are present. Collagen deposition leads to scarring and retraction of the mesentery, leading to the formation of abdominal masses and obstructive symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lists the potential proposed etiologies of MP

| Trauma: abdominal trauma and surgery, post-colonoscopy, using pneumatic Jack-Hammer (Drill) |

| Autoimmune: IgG4-related disease, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, transplant rejection, mixed connective tissue disease, autoimmune hemolytic anemia |

| Malignancy/paraneoplasia: lymphoma, multiple myeloma, thoracic mesothelioma |

| Infectious: tuberculosis, HIV, cryptococcus, schistosomiasis, vibrio cholera |

| Vasculitis: Henoch-Schönlein purpura |

| Medications: pergolide, paroxetine |

MP caries a benign natural history when incidentally found with the majority (70.2–96.5%) of lesions stable on follow-up imaging, some (8–27%) resolve spontaneously, and minority (2.3–16%) progress [17, 19, 34]. However, regardless of the radiologic findings, symptoms may not correlate as 82.4% of those with pain reported spontaneous resolution despite no radiographic changes [16].

Clinical Presentation

In most cases, MP is asymptomatic, found incidentally on cross-sectional imaging. In some cases, they can present with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain (30%–72%). Other nonspecific symptoms like can be present like fever, malaise, weight loss (20–23%), and altered bowel habits with either constipation or diarrhea (20–26%) [3, 12, 35]. A palpable mass in the abdominal cavity can also be a presenting symptom for MP in 35–50% of patients. Masses tend to be located deeply and are poorly defined [3, 4, 12, 35–37]. Rare presentations of MP reported in the literature are rectal bleeding, jaundice, and gastric outlet obstruction [14, 38, 39]. It can also mimic other underlying diseases such as peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancies depending on the size and location [4, 40] and may also be a link to previous trauma, surgery or infection [2]. Diagnosing MP poses therefore a challenge due to the lack of specific symptoms and the variable nature of its presentation (Table 3). The mean clinical progression is usually 6 months ranging from 2 weeks to 16 years. Laboratory inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, leukocytosis is nonspecific and elevated in 14–88%, often secondary to underlying inflammation [4, 9, 12, 19].

Table 3.

Describes the terminology with associated pathology and symptomatology

| Mesenteric lipodystrophy | MP | Retractile mesenteritis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathology | Predominant fat necrosis, foamy macrophages replace mesenteric fat | Predominant chronic inflammation, plasma cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, foreign-body giant cells, and foamy macrophages | Predominant collagen deposition, fibrosis, and inflammation |

| Clinical presentation | Asymptomatic | Pyrexia, abdominal pain, malaise | Mass effect, obstruction |

Diagnosis

From a histological perspective, the disease advances through three stages [18]. Initially, in the first stage known as mesenteric lipodystrophy, mesenteric fat is replaced by a layer of foamy macrophages. Acute inflammatory indicators are typically minimal or absent; the condition tends to manifest without clinical symptoms, and prognosis is favorable. Subsequently, the second stage, termed MP, is characterized by histological findings of an infiltration consisting primarily of plasma cells, along with a few polymorphonuclear leukocytes, foreign-body giant cells, and foamy macrophages. Common symptoms often include fever, abdominal pain, and malaise. The final stage is retractile mesenteritis, characterized by the accumulation of collagen, fibrosis, and inflammation. The deposition of collagen results in scarring and contraction of the mesentery, leading to the development of abdominal masses and symptoms of obstruction. Diagnosis is challenging and typically relies on identifying one of three primary pathological characteristics: fibrosis, chronic inflammation, or fatty infiltration of the mesentery. In many instances, a combination of all three elements is present to some degree [33]. Although biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing MP and excludes malignancy, CT scan is often sufficient. In medical literature, the radiological characteristics of MP are predominantly discussed based on computed tomography (CT) images seen in Figure 1a–d. There are limited articles regarding MP based on magnetic resonance imaging scans. Typically, the inflammatory type of MP appears dark on T1-weighted images and bright on T2-weighted sequences [41–43]. Another form of diagnoses is with biopsy. The diagnosis of MP in the majority of cases is incidental, found on cross-sectional imaging carried out for other reasons. Understandably, the prevalence varies depending on the indication and setting for abdominal imaging. Diagnostic laboratories for detecting MP are not specific. Slight increases in white blood cell count and levels of inflammatory markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein have been observed in as many as 80% of cases and can serve as monitor for treatment response [14]. Anemia and hypoalbuminemia have been documented in 16% and 5% of cases, respectively, and may manifest as nonspecific findings linked to the condition [4, 13]. Figure 2 shows a detailed algorithm in management.

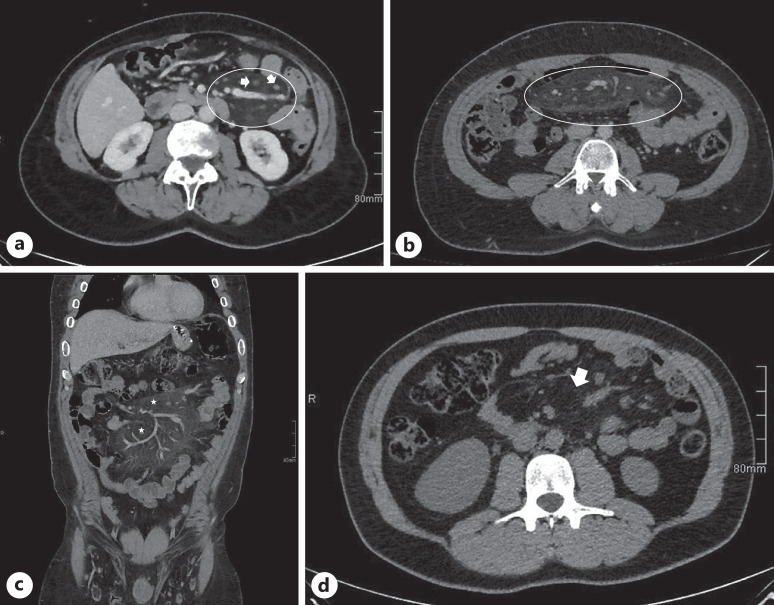

Fig. 1.

CT findings in (a) mild and (b) moderate MP showing multiple subcentimetric mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow) with surrounding mesenteric fat stranding (circle), while (c) and (d) show an inflammatory mesenteric fat mass (circle) with hypodense halo (star) around blood vessels.

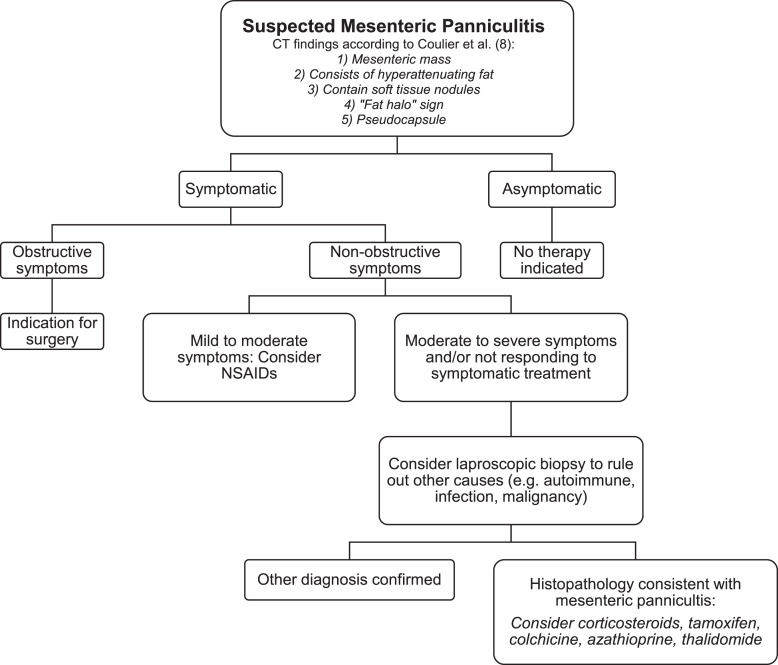

Fig. 2.

Proposed diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for the management of suspected MP.

In a retrospective cross-sectional study done at our radiology department at the American University of Beirut Medical Center, we evaluated the prevalence of MP over a period of 5 years spanning from September 2018 to September 2023. Using an electronic health record search, the diagnosis of MP was made in 1,337 out of a total of 48,637 abdominal CT scans, for an overall prevalence of 2.7%. Within the subset of CT scans ordered from the Emergency Department for evaluation of abdominal pain, 748 out of 7,928 had MP (9.4%).

According to the accepted definition by Coulier [8], the CT diagnosis of MP requires the presence of at least 3 out of 5 typical signs: a well-defined fatty mass at the root of the small bowel mesentery displacing neighboring structures, a higher attenuation than that of retroperitoneal or subcutaneous fat tissue, lymph nodes within this well-defined fatty mass, a hypodense halo surrounding blood vessels and nodes, and a hyperdense pseudo capsule surrounding the mesenteric fat with the lymph nodes within. Figure 1 shows the different severity of MP on CT imaging. It is critical and often challenging to differentiate MP from malignancies. Mesenteric lymph nodes are usually <10 mm in MP, and the presence of larger lymph nodes warrants evaluation by either biopsy or positron emission tomography (PET-CT) [11]. It is also important to note that the presence of an MP soft-tissue nodule >10 mm and associated lymphadenopathy in another abdominopelvic region warrant further workup to rule out an underlying malignancy in patients with MP [44]. Other differential diagnoses are inflammatory pseudo-tumor, desmoid tumor, or pancreatitis. Magnetic resonance imaging and PET-CT are other modalities of diagnosis; however, PET-CT may not be sufficient to detect all malignant lymphoma and biopsy remains the gold standard to rule out malignancy in doubtful cases [45]. Therefore, CT scan remains the diagnostic method of choice. Radiographically, the terms “sclerosing mesenteritis” or “rectractile mesenteritis” are used to describe complicated disease with retraction of the mesentery or encasement of the bowel or vasculature. However, these are not yet unifying criteria [10, 46].

Treatment

Since patients with MP are typically asymptomatic and found incidentally, treatment is seldom required in the majority of cases [47] and is only reserved for symptomatic patients. Patients who present with asymptomatic disease are likely to remain asymptomatic during follow-up and do not require treatment. In fact, it is estimated that only a small percentage, ranging from 1.1 to 6.1 percent, of patients in imaging studies require treatment specifically aimed at sclerosing mesenteritis [5, 6, 21]. For symptomatic patients, different treatments have been suggested, however, based on small case series, case reports, and extrapolation from other fibrosing diseases, such as retroperitoneal fibrosis [48]. Drugs such as corticosteroids, tamoxifen, colchicine, pentoxifylline, progesterone, azathioprine, thalidomide, infliximab, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antibiotics, and a combination of the above have been tried with some success [7, 49–51]. Corticosteroids in combination with tamoxifen have been studied as first-line therapy in a small case series of 20 patients with significant symptoms [12]. They showed 60% response rates within 12–16 weeks, 30% showed persistent symptoms, and 10% progressed. The authors suggest a trial of prednisone 40 mg daily and tamoxifen 10 mg twice daily for up to 4 months, then tapering the prednisone gradually and continuing tamoxifen indefinitely [5]. Combination therapy consisting of 40 mg prednisone and 1 mg colchicine have been studied as first-line treatment in a single-center retrospective study involving 40 patients diagnosed with MP. Among the 35 patients treated with this combination therapy, 85% achieved complete resolution of their symptoms [52]. A retrospective study comparing the different medical treatment for MP reported similar efficacy between prednisone + colchicine and prednisone + tamoxifen in the short term and long term [53]. Patients should be counseled on potential long-term side effects prior to treatment initiation and proper vaccinations should be given. Thalidomide has been evaluated prospectively in a small, open-label pilot study of 5 symptomatic MP patients treated with thalidomide 200 mg daily for 12 weeks [54]. Only 20% (1 patient) achieved clinical remission and 80% (4 patients) achieved clinical response. However, given the side effects of thalidomide (such as peripheral neuropathy and birth defects), it should be reserved for patients who fail corticosteroids and tamoxifen or who have contraindications to those medications. Moreover a retrospective study showed that NSAIDs and antibiotics were effective in most patient having idiopathic MP delineating that its pathophysiology may be either infectious or inflammatory [7]. Treatment with colchicine and/or tamoxifen may be associated with adverse events side effects. The most important side effect of colchicine is gastrointestinal manifestations mostly diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting followed by myalgias [55], while tamoxifen is associated with increased risk of stroke and pulmonary embolism [56, 57], an increased risk of endometrial adenocarcinoma [58], as well as gynecomastia and infertility in men.

Before starting colchicine therapy, it is recommended to do complete blood count, liver function tests with creatinine to check the baseline of the patient’s liver and kidney, particularly in patients with increased risk of accumulation (renal or hepatic impairment, concomitant use of P-gp inhibitors or CYP3A4 inhibitors, chronic therapy) [59]. Additionally, while taking tamoxifen, INR and PT should be monitored and a pregnancy test should be done prior to medication use. Screening for cardiovascular disease risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, liver disease, and prompt evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding is also important [60].

In rare cases of bowel obstruction, ischemia, or perforation, surgery was necessary [61]. In one series, complete or partial resection of the mesenteric mass was achieved in only 30% of patients, and the rest underwent palliative bypass, small bowel resection for ischemic bowel, or adhesiolysis [12]. However, these were highly selected population which are unlikely a representative of what is seen in community practice.

Conclusion

MP is an uncommon idiopathic inflammatory, non-neoplastic condition of unknown etiology that leads to inflammation of adipose tissue of the mesentery. It is generally asymptomatic but if symptoms occur, they are mostly nonspecific. Diagnosis is usually made on CT scan; however, definitive diagnosis requires histopathologic examination that shows inflammation, fibrosis, and fat necrosis. Treatment is not well established and targets symptom relief. If symptomatic, treatment includes NSAIDs, corticosteroids, tamoxifen, and some immunomodulators. Surgery is reserved for more severe presentation such as mass effect, bowel obstruction, or ischemic changes.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature. Ethical approval and patient consent were not required as this study was based on publicly available data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not funded by any sponsor.

Author Contributions

Ala I. Sharara, Cecilio Azar, Mohamad Ali Ibrahim, Zakaria El Kouzi, Ali El Mokahal, Nadine Omran, and Nadim Muallem: study idea, review of literature, and drafting of the manuscript. Zakaria El Kouzi, Ali El Mokahal, Nadine Omran, and Nadim Muallem: acquisition of radiology figure and critical review of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was not funded by any sponsor.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Jura V. Sulla mesenterite retrattile e sclerosante. Policlinico. 1924;31:575–81. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Issa I, Baydoun H. Mesenteric panniculitis: various presentations and treatment regimens. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(30):3827–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH. Sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis and mesenteric lipodystrophy: a single entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21(4):392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharma P, Yadav S, Needham CM, Feuerstadt P. Sclerosing mesenteritis: a systematic review of 192 cases. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10(2):103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Danford CJ, Lin SC, Wolf JL. Sclerosing mesenteritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):867–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daskalogiannaki M, Voloudaki A, Prassopoulos P, Magkanas E, Stefanaki K, Apostolaki E, et al. CT evaluation of mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence and associated diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(2):427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sahin A, Artas H, Eroglu Y, Tunc N, Demirel U, Bahcecioglu IH, et al. An overlooked potentially treatable disorder: idiopathic mesenteric panniculitis. Med Princ Pract. 2017;26(6):567–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coulier B. Mesenteric panniculitis. Part 2: prevalence and natural course: MDCT prospective study. JBR-BTR. 2011;94(5):241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gögebakan Ö, Osterhoff MA, Albrecht T. Mesenteric panniculitis (MP): a frequent coincidental CT finding of debatable clinical significance. Rofo. 2018;190(11):1044–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roson N, Garriga V, Cuadrado M, Pruna X, Carbó S, Vizcaya S, et al. Sonographic findings of mesenteric panniculitis: correlation with CT and literature review. J Clin Ultrasound. 2006;34(4):169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canyigit M, Koksal A, Akgoz A, Kara T, Sarisahin M, Akhan O. Multidetector-row computed tomography findings of sclerosing mesenteritis with associated diseases and its prevalence. Jpn J Radiol. 2011;29(7):495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Akram, S, Pardi, DS, Schaffner, JA, Smyrk, TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and outcome in ninety-two patients .Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(5):589–24; quiz 523–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sulbaran M, Chen FK, Farraye FA, Hashash JG. A clinical review of mesenteric panniculitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;19(4):211–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Green MS, Chhabra R, Goyal H. Sclerosing mesenteritis: a comprehensive clinical review. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(17):336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lim HW, Sultan KS. Sclerosing mesenteritis causing chylous ascites and small bowel perforation. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:696–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Putte-Katier N, van Bommel EFH, Elgersma OE, Hendriksz TR. Mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence, clinicoradiological presentation and 5-year follow-up. Br J Radiol. 2014;87(1044):20140451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Badet N, Sailley N, Briquez C, Paquette B, Vuitton L, Delabrousse É. Mesenteric panniculitis: still an ambiguous condition. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96(3):251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delgado Plasencia L, Rodríguez Ballester L, López-Tomassetti Fernández EM, Hernández Morales A, Carrillo Pallarés A, Hernández Siverio N. Paniculitis mesentérica: experiencia en nuestro centro. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2007;99(5):291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daskalogiannaki M, Voloudaki A, Prassopoulos P, Magkanas E, Stefanaki K, Apostolaki E, et al. CT evaluation of mesenteric panniculitis: prevalence and associated diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(2):427–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wagner C, Dachman A, Ehrenpreis ED. Mesenteric panniculitis, sclerosing mesenteritis and mesenteric lipodystrophy: descriptive review of a rare condition. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2022;35(4):342–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horton KM, Lawler LP, Fishman EK. CT findings in sclerosing mesenteritis (panniculitis): spectrum of disease. Radiographics. 2003;23(6):1561–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaya C, Bozkurt E, Yazıcı P, İdiz UO, Tanal M, Mihmanlı M. Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of mesenteric panniculitis from the surgical point of view. Turk J Surg. 2018;34(2):121–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Patel N, Saleeb SF, Teplick SK. General case of the day. Mesenteric panniculitis with extensive inflammatory involvement of the peritoneum and intraperitoneal structures. Radiographics. 1999;19(4):1083–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schweistein H, Weintraub Y, Hornik-Lurie T, Haskiya H, Levin S, Ringel Y, et al. Mesenteric panniculitis is associated with cardiovascular risk-factors: a case-control study. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54(12):1657–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Özer Gökaslan Ç, Aslan E, Demirel E, Yücel A. Relationship of mesenteric panniculitis with visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Turk J Med Sci. 2020;50(1):44–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cuff R, Landercasper J, Schlack S. Sclerosing mesenteritis. Surgery. 2001;129(4):509–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McCrystal DJ, O’Loughlin BS, Samaratunga H. Mesenteric panniculitis: a mimic of malignancy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(3):237–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shah AN, You CH. Mesenteric lipodystrophy presenting as an acute abdomen. South Med J. 1982;75(8):1025–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gögebakan Ö, Albrecht T, Osterhoff MA, Reimann A. Is mesenteric panniculitis truely a paraneoplastic phenomenon? A matched pair analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82(11):1853–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilkes A, Griffin N, Dixon L, Dobbs B, Frizelle FA. Mesenteric panniculitis: a paraneoplastic phenomenon? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(7):806–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Halligan S, Plumb A, Taylor S. Mesenteric panniculitis: systematic review of cross-sectional imaging findings and risk of subsequent malignancy. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(12):4531–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hussain I, Ishrat S, Aravamudan VM, Khan SR, Mohan BP, Lohan R, et al. Mesenteric panniculitis does not confer an increased risk for cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2022;101(17):e29143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seo M, Okada M, Okina S, Ohdera K, Nakashima R, Sakisaka S. Mesenteric panniculitis of the colon with obstruction of the inferior mesenteric vein: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(6):885–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Buchwald P, Diesing L, Dixon L, Wakeman C, Eglinton T, Dobbs B, et al. Cohort study of mesenteric panniculitis and its relationship to malignancy. Br J Surg. 2016;103(12):1727–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Durst AL, Freund H, Rosenmann E, Birnbaum D. Mesenteric panniculitis: review of the leterature and presentation of cases. Surgery. 1977;81(2):203–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Parra-Davila E, McKenney MG, Sleeman D, Hartmann R, Rao RK, McKenney K, et al. Mesenteric panniculitis: case report and literature review. Am Surg. 1998;64(8):768–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Monahan DW, Poston WK Jr, Brown GJ. Mesenteric panniculitis. South Med J. 1989;82(6):782–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sivrioglu AK, Saglam M, Deveer M, Sonmez G. Another reason for abdominal pain: mesenteric panniculitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Patel A, Alkawaleet Y, Young M, Reddy C. Mesenteric panniculitis: an unusual presentation of abdominal pain. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Al-Omari MH, Qararha K, Garaleh M, Smadi MM, Hani MB, Elheis M. Mesenteric panniculitis: comparison of computed tomography findings in patients with and without malignancy. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Buragina G, Magenta Biasina A, Carrafiello G. Clinical and radiological features of mesenteric panniculitis: a critical overview. Acta Biomed. 2019;90(4):411–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ezhapilli SR, Moreno CC, Small WC, Hanley K, Kitajima HD, Mittal PK. Mesenteric masses: approach to differential diagnosis at MRI with histopathologic correlation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(4):753–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Popkharitov AI, Chomov GN. Mesenteric panniculitis of the sigmoid colon: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2007;1:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grégory J, Dana J, Yang I, Chong J, Drevon L, Ronot M, et al. CT features associated with underlying malignancy in patients with diagnosed mesenteric panniculitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2022;103(9):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ehrenpreis ED, Rao AS, Aki R, Brown H, Pae T, Boiskin I. Normal positron emission tomography-computerized tomogram in a patient with apparent mesenteric panniculitis: biopsy is still the answer. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2009;3(1):131–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kronthal AJ, Kang YS, Fishman EK, Jones B, Kuhlman JE, Tempany CM. MR imaging in sclerosing mesenteritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156(3):517–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hillemand CG, Clarke R, Murphy SJ. Abdominal pain from sclerosing mesenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(4):A22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vaglio A, Palmisano A, Alberici F, Maggiore U, Ferretti S, Cobelli R, et al. Prednisone versus tamoxifen in patients with idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9788):338–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bala A, Coderre SP, Johnson DR, Nayak V. Treatment of sclerosing mesenteritis with corticosteroids and azathioprine. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15(8):533–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Généreau T, Bellin MF, Wechsler B, Le TH, Bellanger J, Grellet J, et al. Demonstration of efficacy of combining corticosteroids and colchicine in two patients with idiopathic sclerosing mesenteritis. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(4):684–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kapsoritakis AN, Rizos CD, Delikoukos S, Kyriakou D, Koukoulis GK, Potamianos SP. Retractile mesenteritis presenting with malabsorption syndrome. Successful treatment with oral pentoxifylline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17(1):91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Alsuhaimi MA, Alshowaiey RA, Alsumaihi AS, Aldhafeeri SM. Mesenteric panniculitis various presentations and management: a single institute ten years, experience. Ann Med Surg. 2022;80:104203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cortés P, Ghoz HM, Mzaik O, Alhaj Moustafa M, Bi Y, Brahmbhatt B, et al. Colchicine as an alternative first-line treatment of sclerosing mesenteritis: a retrospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(6):2403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ginsburg PM, Ehrenpreis ED. A pilot study of thalidomide for patients with symptomatic mesenteric panniculitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(12):2115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Slobodnick A, Shah B, Krasnokutsky S, Pillinger MH. Update on colchicine, 2017. Rheumatol. 2018;57(Suppl l_1):i4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin HF, Liao KF, Chang CM, Lin CL, Lai SW, Hsu CY. Correlation of the tamoxifen use with the increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in elderly women with breast cancer: a case-control study. Medicine. 2018;97(51):e12842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bushnell CD, Goldstein LB. Risk of ischemic stroke with tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Neurology. 2004;63(7):1230–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fiorica JV, Brunetto VL, Hanjani P, Lentz SS, Mannel R, Andersen W, et al. Phase II trial of alternating courses of megestrol acetate and tamoxifen in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92(1):10–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gómez-Lumbreras A, Boyce RD, Villa-Zapata L, Tan MS, Hansten PD, Horn J, et al. Drugs that interact with colchicine via inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein: a signal detection analysis using a database of spontaneously reported adverse events (FAERS). Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(10):1137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Neven P, Vernaeve H. Guidelines for monitoring patients taking tamoxifen treatment. Drug Saf. 2000;22(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Endo K, Moroi R, Sugimura M, Fujishima F, Naitoh T, Tanaka N, et al. Refractory sclerosing mesenteritis involving the small intestinal mesentery: a case report and literature review. Intern Med. 2014;53(13):1419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.