Abstract

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) can affect various eye movements, making eye tracking a potential means for disease monitoring. In this study, we evaluated the feasibility of ALS patients self-recording their eye movements using the “EyePhone,” a smartphone eye-tracking application.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled ten participants and provided them with an iPhone equipped with the EyePhone app and a PowerPoint presentation with step-by-step recording instructions. The goal was for the participants to record their eye movements (saccades and smooth pursuit) without the help of the study team. Afterward, a trained physician administered the same tests using video-oculography (VOG) goggles and asked the participants to complete a questionnaire regarding their self-recording experience.

Results

All participants successfully completed the self-recording process without assistance from the study team. Questionnaire data indicated that participants viewed self-recording with EyePhone favorably, considering it easy and comfortable. Moreover, 70% indicated that they prefer self-recording to being recorded by VOG goggles.

Conclusion

With proper instruction, ALS patients can effectively use the EyePhone to record their eye movements, potentially even in a home environment. These results demonstrate the potential for smartphone eye-tracking technology as a viable and self-administered tool for monitoring disease progression in ALS, reducing the need for frequent clinic visits.

Keywords: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Eye movements, Health technology, Smartphone eye-tracking application

Introduction

Eye movements are believed to be preserved well into the late stages of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [1], which is a motor neuron disease defined by degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons [2]. However, this prevailing teaching in neurology is based mainly on visible clinical evaluations rather than objective, quantified eye-movement metrics. Increasing availability of eye-movement tracking has yielded a multitude of ocular motor abnormalities in ALS, including saccadic intrusions, slow saccades, and abnormal smooth pursuit [3–6]. Furthermore, some studies have found a significant association between the degree of eye-movement involvement and the clinical progression of ALS [7–9].

In both clinical trials and clinical practice, nuanced biomarkers are important metrics to objectively assess clinical status and therapeutic effects. Nevertheless, there are a lack of proper biomarkers for ALS, which is considered a barrier for developing effective treatments [10]. Normally, patients must be tracked in an in-person clinical setting. Self-utilized eye-tracking technology may provide an accessible solution. First, longitudinal eye tracking may mark nuanced disease progression. Second, the continuous collection of self-utilized data can circumvent the inconvenience of patients and caregivers traveling long distances for research and clinical appointments [11, 12]. Finally, as late-stage ALS patients rely on eye-tracking technology to communicate with their caregivers [13], it is dually important to understand the eye-movement abnormalities that could potentially affect this important means of communication.

We evaluated the feasibility of ALS patients self-recording of eye movements with our smartphone application named “EyePhone” [14]. The hypothesized power of “EyePhone” is the ability to effectively and repeatedly track eye-movement abnormalities outside of a clinical appointment.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled participants at Johns Hopkins Outpatient ALS Center between June 2022 and January 2023. All patients with a diagnosis of ALS were considered for our study regardless of the severity of their symptoms. The study team provided participants with an iPhone 11 Pro (Apple, CA) with EyePhone app installed, a small phone stand, and a laptop to view the instruction slide-deck.

The EyePhone app has been developed in-house by our study team using the Swift programming language using the Apple’s ARKIT developer tools. As the app currently relies on facial and eye detection features embedded in iPhone’s front camera, it only runs on iPhone models with the FaceID feature (iPhone X and later). The app is maintained and updated by our study team and is currently compatible with the latest iOS version (iOS 17.1). EyePhone is still in development and is not commercially available. However, interested parties are welcome to reach out to the corresponding author for a demo of the app. We have previously published several papers about the development of the EyePhone application where we have highlighted in detail the development, calibration, and preliminary assessment of the app’s accuracy based on the current standard of care (video-oculography [VOG] goggles) [14–16].

We prepared a two-part presentation including an introductory video for general features of the app and the tests to perform, and a step-by-step self-paced guide for performing eye-movement tests and recording them. We loaded the PowerPoint containing the self-recording instructions on a laptop and placed it beside the smartphone set-up. All participants viewed the same instructional presentation.

The eye-movement test comprised of the following:

-

1.

Test of horizontal and vertical saccades: the participants were instructed to position their face 30 cm from the phone (using EyePhone’s distance measure feature) and run the saccade test in the app. The test consisted of two red dots that appeared alternately on the screen. The dots were placed 12.5 cm apart, spanning 20° of the visual field at a 30-cm distance. After recording vertical saccades, the patients were instructed to rotate the phone 90° counter clockwise to record horizontal saccades in a similar manner.

-

2.

Test of horizontal and vertical smooth pursuit: the instructions to this test were similar to the saccade test, except patients were instructed to follow the red dot as it moved across the screen. The dot was designed to move at a velocity of 10°/second at a 30-cm distance.

We instructed the participants to refrain from asking the study team for help during the self-recording process. They were, however, encouraged to use the help of their caregivers as needed. A member of the study team was present during the self-recording process only to address any unanticipated technical issues and note possible difficulties.

Once the participants successfully completed the self-recording session, a trained study team member recorded their eye movements with the ICS Impulse VOG goggles (Natus Medical Inc., WI). These goggles connect to their own software (OtoSuite Vestibular) and provide eye-movement traces and metrics. After calibrating the VOG goggles, we tested saccades by the built-in saccade testing sequence that tests horizontal saccades of 7.5 and 15-degree amplitude. We recorded the horizontal and vertical smooth pursuit using the same moving target on EyePhone while using the gaze recording function on VOG goggles.

After the recording process, we asked the participants to complete a survey about their experience recording their eye movements using EyePhone and its comparison to being recorded by a study team member using the VOG. The EyePhone application saves the eye-movement data sampled at 60 Hz in a CSV (comma-separated values) file. We visualized the eye traces by importing the data files into MATLAB R2023 and graphing eye position by time for each recording. We conducted a preliminary analysis of the comparison of mean smooth pursuit gain between the ALS patients and a sample of previously recorded healthy volunteers using Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test by IBM SPSS statistics 29.0.

Results

We enrolled 10 participants, 70% female, with an average age of 56.5 ± 12.2 years. The average ALS functional rating score (ALS-FRS) was 26.8 ± 6.3 out of 48. The educational background of the patients encompassed a range from “some college education with no degree” to “graduate or professional degree” with majority of the participants (40%) having completed a bachelor’s degree as the highest level of their education.

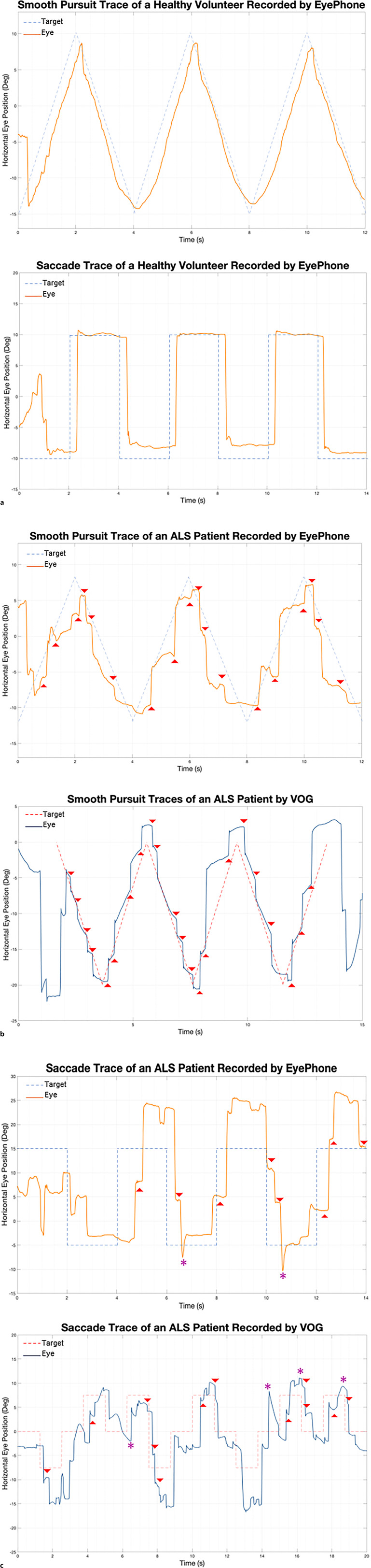

All participants successfully completed the self-recording process without help from the study team. Figure 1 demonstrates traces of eye movements obtained by the participants and corresponding VOG traces obtained by the study team. None of the participants experienced any pain or discomfort during the self-recording process.

Fig. 1.

a Eye-movement traces of a healthy volunteer obtained previously by the study team. Note how the eye movements (solid orange line) parallel the target trajectory (dashed blue line). b Smooth pursuit traces of an ALS patient obtained by EyePhone (left) and VOG (right). Note how in both traces as the eyes cannot keep up with the target (dashed line) the make saccadic compensatory movements (highlighted by red arrowheads). c Saccade traces of an ALS patient obtained by EyePhone (left) and VOG (right). Note how the eye traces (solid lines) depict that the eyes have to make successive small movements (hypometric saccades highlighted by red arrowhead) as opposed to one big movement (compare to the healthy volunteer figure in a). VOG, video-oculography.

Usability Statistics

Table 1 summarizes the participants’ responses to our usability questionnaire. As evident in the table, all participants agreed that recording their eye movements with EyePhone was a comfortable, easy, and feasible task. Moreover, all participants agreed (70% strongly agreed) that they were able to easily follow the instructional video, and if they were provided the instructions, they would be able to record their eye movements at home using their own smartphone.

Table 1.

Summary of the responses to the usability questionnaire

| Question | Strongly disagree, % | Disagree, % | Neutral, % | Agree, % | Strongly agree, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It was comfortable to record the eye movements using the phone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 40 |

| It was easy to adjust the phone in the recommended position in front of my face | 0 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 30 |

| It was easy to follow the instructions provided by the instructional video | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 70 |

| It was easy to perform the tests without help from the study team | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 50 |

| It was easy to navigate between the features of the phone application | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 70 |

| It was easy for me to perform the saccade test (looking at the red dot at different locations on the screen) and recording my eye movements using the phone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 60 |

| It was easy for me to perform the smooth pursuit test (following the red dot as it moves on the screen) and recording my eye movements using the phone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 80 |

| If I were provided with the instructional video, I would be able to record my eye movements at home using my smartphone? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 60 |

When asked about their preference between EyePhone and VOG, 70% of the participants (n = 7) stated that they would prefer EyePhone if they were to take the eye-movement tests again. To take the element of commute into account, we asked the latter half of our study population (n = 5) whether they would prefer coming to the clinic to have their eye movements recorded by VOG or record their eye movements themselves at home using EyePhone and an instructional video, assuming that both methods’ quality was acceptable to their care provider. All 5 patients chose self-recording with EyePhone at home over VOG recording at clinic.

Data Quality and Eye-Movement Traces

By visualizing the eye-movement traces obtained from EyePhone self-recordings and comparing them to the VOG traces (obtained by the study team) of the same individuals, we were able to detect some of the previously described eye-movement abnormalities in ALS. Moreover, we compared the self-recorded traces of the ALS patients to healthy volunteer traces previously obtained by the study team.

Figure 1a represents a smooth pursuit trace and a saccade trace of a healthy volunteer previously obtained by the study team using EyePhone. Figure 1b depicts an example of abnormal (i.e., choppy) smooth pursuit picked up from the self-recorded traces of one of the participants with ALS. The trace obtained by a trained operator using the VOG shows a similar abnormality. Figure 1c highlights in the same fashion how a self-recorded EyePhone trace of one other participant with ALS has saccade abnormalities similar to those picked up by the VOG goggles. Furthermore, a preliminary analysis comparing the smooth pursuit data obtained by EyePhone showed that healthy volunteers had a significantly higher horizontal smooth pursuit gain compared to the ALS patients (online suppl. Fig. 1; Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000538992).

Discussion

The data from our usability study indicates that with video instruction, ALS patients can easily use the EyePhone to record their eye movements with the help of their caregivers as needed. So far, the use of eye-tracking technology has been limited to enhancing communication in late stages of ALS [17], and the diagnostic and prognostic use of this technology is rare – if not absent – outside of research. However, as the search for a reliable biomarker continues to pose a barrier to ALS treatment trials [10], smartphone eye-tracking could serve more than it has previously been credited.

A nuance of our pilot study was observing how well patients with a wide range of ALS-FRS scores interacted with this technology. The participant with the lowest ALS-FRS score (worst disability), scored 0 in the first four categories (speech, salivation, swallowing, and handwriting), but was nevertheless able to complete the recording process. This indicates that a combination of proper instruction, help from caregivers, and a user-friendly application, can overcome physical barriers that one might find, even in later stages of ALS.

Although the focus of this study was evaluating the feasibility of eye-movement self-recording, the preliminary data show promising findings as well. Comparing the traces extracted from recordings obtained by the ALS patients to healthy volunteers, we were able to highlight some of the previously established eye-movement abnormalities in ALS [1, 3, 6]. Furthermore, our preliminary data show similar abnormalities confirmed by the standard clinical reference VOG.

By enabling patients to obtain eye-movement traces comparable to those of the clinical reference (VOG Goggles), EyePhone can serve as a readily available tool for obtaining valuable biomarkers that could shape the future of ALS assessment and resource allocation. Nonetheless, we must emphasize that this is just the beginning of a long path toward optimizing and calibrating EyePhone for the use by ALS patients. While we had previously tested and validated EyePhone in other clinical and research environments, this was our first attempt at evaluating the participants’ capability and experience using the EyePhone app. Through the course of this pilot study, we have learned valuable insights – regarding the usability of the app and the obstacles in the path of an optimized patient-facing app – that would guide us in shaping the app for a better user experience combined with reliable output.

Providing an accessible self-utilized eye-movement recording tool also aligns with recent research that indicates high correlation of speech and voice abnormalities with progression of the disease [18]. Further, such self-utilized disease tracking is in line with burgeoning reports that continuous, effective, data obtained without the need for clinical visits can and should be used for marking disease progression both for research [11, 12] and clinical care [19, 20]. Understanding the constraints that affect patients with advanced disease, especially in regard to mobility, in-home solutions like EyePhone app hold the potential to change patient follow-up in ALS trials and real life.

Conclusion

In this feasibility study we showed that ALS patients can be instructed to record their eye movements using a smartphone application and produce eye-movement traces on par those collected using the standard of care VOG by trained staff.

Limitations

Our study was a feasibility study, limited by the small sample size. Furthermore, while we were able to detect eye-movement abnormalities based on the EyePhone traces, it is important to consider that the methodology of this study limits us from drawing conclusions on the accuracy of such self-recorded traces in detecting abnormalities. Future studies with larger sample size and more controlled protocols will aid us in establishing the accuracy of this application.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. David S. Zee and Dr. Jeffrey Rothstein for sharing their invaluable expertise in the fields of eye movements and ALS.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB00258938). After providing detailed information about the study, we obtained written informed consents from all the participants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

David Newman-Toker, Jorge Otero Millan, Taylor Max Parker, and Nathan Farrell have a provisional patent application regarding the use of EyePhone in tracking eye and head position. David Newman-Toker, Ali S. Saber Tehrani, Jorge Otero Millan, Hector Rieiro, Pouya B. Bastani, Taylor Max Parker, and Nathan Farrell have a provisional patent application regarding using the EyePhone for recording saccades and smooth pursuit.

Funding Sources

This study received no funding.

Author Contributions

P.B.B., A.S.T., D.N.T., L.L.C., K.R., and S.R.Z. contributed to the conception and design of the study. P.B.B., A.S.T., S.B., N.F., T.M.P., J.O.M., H.R., A.H., L.L.C., A.U., K.R., and S.R.Z. contributed to acquisition and analysis of the data. P.B.B., A.S.T., D.R., and S.R.Z. contributed to drafting a significant portion of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to restrictions by our institutional review board. However, aggregate data will be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (S.R.Z.).

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Leigh RJ, Zee DS. The neurology of eye movements. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brooks BR. El escorial world federation of neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on motor neuron diseases/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis of the world federation of neurology research group on neuromuscular diseases and the el escorial “clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis” workshop contributors. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124(Suppl l):96–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharma R, Hicks S, Berna CM, Kennard C, Talbot K, Turner MR. Oculomotor dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(7):857–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gorges M, Müller H-P, Lulé D, Del Tredici K, Brettschneider J, Keller J, et al. Eye movement deficits are consistent with a staging model of pTDP-43 pathology in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shaunak S, Orrell RW, O’Sullivan E, Hawken MB, Lane RJM, Henderson L, et al. Oculomotor function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: evidence for frontal impairment. Ann Neurol. 1995;38(1):38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donaghy C, Thurtell MJ, Pioro EP, Gibson JM, Leigh RJ. Eye movements in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and its mimics: a review with illustrative cases. Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(1):110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo X, Liu X, Ye S, Liu X, Yang X, Fan D. Eye movement abnormalities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Sci. 2022;12(4):489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Poletti B, Solca F, Carelli L, Diena A, Colombo E, Torre S, et al. Association of clinically evident eye movement abnormalities with motor and cognitive features in patients with motor neuron disorders. Neurology. 2021;97(18):e1835–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakamagoe K, Matsumoto S, Touno N, Tateno I, Koganezawa T. Saccadic oscillations as a biomarker of clinical symptoms in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2023;44(8):2787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katyal N, Govindarajan R. Shortcomings in the current amyotrophic lateral sclerosis trials and potential solutions for improvement. Front Neurol. 2017;8:521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hobson EV, Baird WO, Partridge R, Cooper CL, Mawson S, Quinn A, et al. The TiM system: developing a novel telehealth service to improve access to specialist care in motor neurone disease using user-centered design. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2018;19(5–6):351–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chipika RH, Finegan E, Li Hi Shing S, Hardiman O, Bede P. Tracking a fast-moving disease: longitudinal markers, monitoring, and clinical trial endpoints in ALS. Front Neurol. 2019;10:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasqualotto E, Matuz T, Federici S, Ruf CA, Bartl M, Olivetti Belardinelli M, et al. Usability and workload of access technology for people with severe motor impairment: a comparison of brain-computer interfacing and eye tracking. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2015;29(10):950–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parker TM, Farrell N, Otero-Millan J, Kheradmand A, McClenney A, Newman-Toker DE. Proof of concept for an “eyePhone” app to measure video head impulses. Digit Biomark. 2021;5(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bastani PB, Rieiro H, Badihian S, Otero-Millan J, Farrell N, Parker M, et al. Quantifying induced nystagmus using a smartphone eye tracking application (EyePhone). J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13(2):e030927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parker TM, Badihian S, Hassoon A, Saber Tehrani AS, Farrell N, Newman-Toker DE, et al. Eye and head movement recordings using smartphones for telemedicine applications: measurements of accuracy and precision. Front Neurol. 2022;13:789581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caligari M, Godi M, Guglielmetti S, Franchignoni F, Nardone A. Eye tracking communication devices in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: impact on disability and quality of life. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013;14(7–8):546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agurto C, Ahmad O, Cecchi GA, Norel R, Pietrowicz M, Eyigoz EK, et al. Analyzing progression of motor and speech impairment in ALS. IEEE; 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeiler SR, Abshire Saylor M, Chao A, Bahouth M. Telemedicine services for the delivery of specialty home-based neurological care. Telemed J E Health; 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drazich BF, Abshire Saylor M, Zeiler SR, Bahouth MN. Providers’ perceptions of neurology care delivered through telemedicine technology. Telemed J e Health. 2023;29(5):761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to restrictions by our institutional review board. However, aggregate data will be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author (S.R.Z.).