The curriculum represents the expression of educational ideas in practice. The word curriculum has its roots in the Latin word for track or race course. From there it came to mean course of study or syllabus. Today the definition is much wider and includes all the planned learning experiences of a school or educational institution.

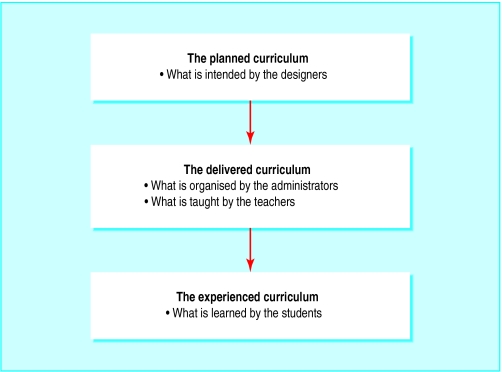

The curriculum must be in a form that can be communicated to those associated with the learning institution, should be open to critique, and should be able to be readily transformed into practice. The curriculum exists at three levels: what is planned for the students, what is delivered to the students, and what the students experience.

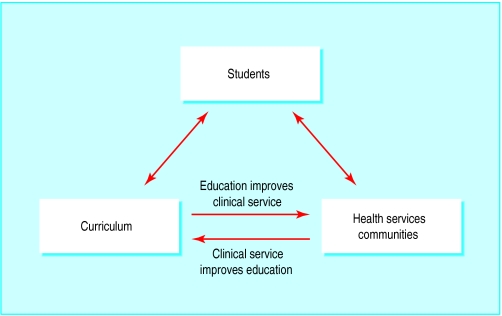

A curriculum is the result of human agency. It is underpinned by a set of values and beliefs about what students should know and how they come to know it. The curriculum of any institution is often contested and problematic. Some people may support a set of underlying values that are no longer relevant. This is the so called sabretoothed curriculum, which is based on the fable of the cave dwellers who continued to teach about hunting the sabretoothed tiger long after it became extinct. In contemporary medical education it is argued that the curriculum should achieve a “symbiosis” with the health services and communities in which the students will serve. The values that underlie the curriculum should enhance health service provision. The curriculum must be responsive to changing values and expectations in education if it is to remain useful.

Elements of a curriculum

If curriculum is defined more broadly than syllabus or course of study then it needs to contain more than mere statements of content to be studied. A curriculum has at least four important elements: content; teaching and learning strategies; assessment processes; and evaluation processes.

The process of defining and organising these elements into a logical pattern is known as curriculum design. Curriculum writers have tried to place some order or rationality on the process of designing a curriculum by advocating models.

There are two main types: prescriptive models, which indicate what curriculum designers should do; and descriptive models, which purport to describe what curriculum designers actually do. A consideration of these models assists in understanding two additional key elements in curriculum design: statements of intent and context.

Curriculum models

Prescriptive models

What curriculum designers should do

How to create a curriculum

Descriptive models

What curriculum designers actually do

What a curriculum covers

Prescriptive models

Prescriptive models are concerned with the ends rather than the means of a curriculum. One of the more well known examples is the “objectives model,” which arose from the initial work of Ralph Tyler in 1949. According to this model, four important questions are used in curriculum design.

Objectives model—four important questions*

What educational purposes should the institution seek to attain?

What educational experiences are likely to attain the purposes?

How can these educational experiences be organised effectively?

How can we determine whether these purposes are being attained?

*Based on Tyler R. Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1949

The first question, about the “purposes” to be obtained, is the most important one. The statements of purpose have become known as “objectives,” which should be written in terms of changed behaviour among learners that can be easily measured. This was interpreted very narrowly by some people and led to the specification of verbs that are acceptable and those that are unacceptable when writing the so called “behavioural objectives.” Once defined, the objectives are then used to determine the other elements of the curriculum (content; teaching and learning strategies; assessment; and evaluation).

Behavioural objectives*

| Acceptable verbs | Unacceptable verbs |

|---|---|

| • To write | • To know |

| • To recite | • To understand |

| • To identify | • To really understand |

| • To differentiate | • To appreciate |

| • To solve | • To fully appreciate |

| • To construct | • To grasp the significance of |

| • To list | • To enjoy |

| • To compare | • To believe |

| • To contrast | • To have faith in |

| *From Davies I. Objectives in curriculum design. London: McGraw Hill, 1976 | |

This model has attracted some criticism—for example, that it is difficult and time consuming to construct behavioural objectives. A more serious criticism is that the model restricts the curriculum to a narrow range of student skills and knowledge that can be readily expressed in behavioural terms. Higher order thinking, problem solving, and processes for acquiring values may be excluded because they cannot be simply stated in behavioural terms. As a result of such criticism the objectives model has waned in popularity. The importance of being clear about the purpose of the curriculum is well accepted.

Clearly stated objectives provide a good starting point, but behavioural objectives are no longer accepted as the “gold standard” in curriculum design

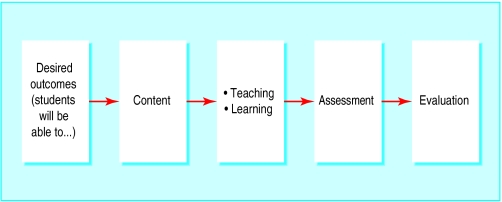

More recently, another prescriptive model of curriculum design has emerged. “Outcomes based education” is similar in many respects to the objectives model and again starts from a simple premise—the curriculum should be defined by the outcomes to be obtained by students. Curriculum design proceeds by working “backwards” from outcomes to the other elements (content; teaching and learning experiences; assessment; and evaluation).

Example of statements of intent

Aim

To produce graduates with knowledge and skills for treating common medical conditions

Objectives

To identify the mechanisms underlying common diseases of the circulatory system

To develop skills in history taking for diseases of the circulatory system

Broad outcome

Graduates will attain knowledge and skills for treating common medical conditions

Students will identify the mechanisms underlying common diseases of the circulatory system

Students will acquire skills in history taking for diseases of the circulatory system

The use of outcomes is becoming more popular in medical education, and this has the important effect of focusing curriculum designers on what the students will do rather than what the staff do. Care should be taken, however, to focus only on “significant and enduring” outcomes. An exclusive concern with specific competencies or precisely defined knowledge and skills to be acquired may result in the exclusion of higher order content that is important in preparing medical professionals.

Although debate may continue about the precise form of these statements of intent (as they are known), they constitute an important element of curriculum design. It is now well accepted that curriculum designers will include statements of intent in the form of both broad curriculum aims and more specific objectives in their plans. Alternatively, intent may be expressed in terms of broad and specific curriculum outcomes. The essential function of these statements is to require curriculum designers to consider clearly the purposes of what they do in terms of the effects and impact on students.

Situational analysis*

| External factors | Internal factors |

| • Societal expectations and changes | • Students |

| • Expectations of employers | • Teachers |

| • Community assumptions and values | • Institutional ethos and structure |

| • Nature of subject disciplines | • Existing resources |

| • Nature of support systems | • Problems and shortcomings in existing curriculum |

| • Expected flow of resources | *From Reynolds J, Skilbeck M. Culture and the classroom. London: Open Books, 1976 |

Descriptive models

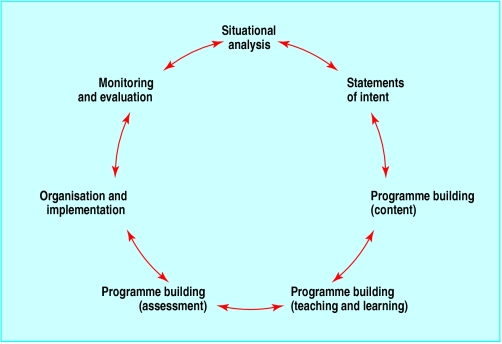

An enduring example of a descriptive model is the situational model advocated by Malcolm Skilbeck, which emphasises the importance of situation or context in curriculum design. In this model, curriculum designers thoroughly and systematically analyse the situation in which they work for its effect on what they do in the curriculum. The impact of both external and internal factors is assessed and the implications for the curriculum are determined.

Although all steps in the situational model (including situational analysis) need to be completed, they do not need to be followed in any particular order. Curriculum design could begin with a thorough analysis of the situation of the curriculum or the aims, objectives, or outcomes to be achieved, but it could also start from, or be motivated by, a review of content, a revision of assessment, or a thorough consideration of evaluation data. What is possible in curriculum design depends heavily on the context in which the process takes place.

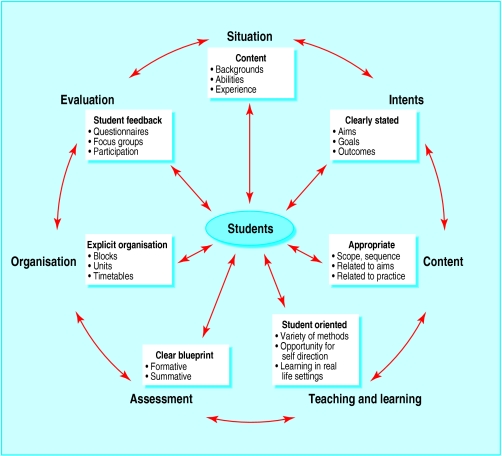

All the elements in curriculum design are linked. They are not separate steps. Content should follow from clear statements of intent and must be derived from considering external and internal context. But equally, content must be delivered by appropriate teaching and learning methods and assessed by relevant tools. No one element—for example, assessment—should be decided without considering the other elements.

Curriculum maps

Curriculum maps provide a means of showing the links between the elements of the curriculum. They also display the essential features of the curriculum in a clear and succinct manner. They provide a structure for the systematic organisation of the curriculum, which can be represented diagrammatically and can provide the basis for organising the curriculum into computer databases.

The starting point for the maps may differ depending on the audience. A map for students will place them at the centre and will have a different focus from a map prepared for teachers, administrators, or accrediting authorities. They all have a common purpose, however, in showing the scope, complexity, and cohesion of the curriculum.

Curriculum maps with computer based graphics with “click-on” links are an excellent format. The maps provide one way of tracing the links between the curriculum as planned, as delivered, and as experienced. But like all maps, a balance must be achieved between detail and overall clarity of representation.

Further reading

Bligh J, Prideaux D, Parsell G. PRISMS: new educational strategies for medical education. Med Educ 2001;35:520-1

Harden R, Crosby J, Davis M. Outcome based education: part 1—an introduction to outcomes-based education. Med Teach 1991;21(1):7-14

Harden R. Curriculum mapping: a tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Med Teach 2000;23(2):123-7

Prideaux D. The emperor's new clothes: from objectives to outcomes. Med Educ 2000;34:168-9

Print M. Curriculum development and design. Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1993.

Figure.

Three levels of a curriculum

Figure.

“Symbiosis” necessary for a curriculum. From Bligh J et al (see “Further reading” box)

Figure.

Outcomes based curriculum (defining a curriculum “backwards”—that is, from the starting point of desired outcomes)

Figure.

The situational model, which emphasises the importance of situation or context in curriculum design

Figure.

Example of a curriculum map from the students' perspective. Each of the boxes representing the elements of design can be broken down into further units and each new unit can be related to the others to illustrate the interlinking of all the components of the curriculum

Footnotes

David Prideaux is professor and head of the Office of Medical Education in the School of medicine at Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia.

The ABC of learning and teaching in medicine is edited by Peter Cantillon, senior lecturer in medical informatics and medical education, National University of Ireland, Galway, Republic of Ireland; Linda Hutchinson, director of education and workforce development and consultant paediatrician, University Hospital Lewisham; and Diana F Wood, deputy dean for education and consultant endocrinologist, Barts and the London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London. The series will be published as a book in late spring.