Abstract

We examined the associations between women’s behavioral coping responses during sexual assault and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and the moderating role of alexithymia in college women (N = 152). Immobilized responses (b = 0.52, p < .001), childhood SA (b = 0.18, p = .01), and alexithymia (b = 0.34, p < .001) significantly predicted PTSD. The interaction between immobilized responses and alexithymia was significant (b = 0.39, p = .002), indicating a stronger association for those higher in alexithymia. Immobilized responses are associated with PTSD, particularly for those with difficulty identifying and labeling emotions.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, sexual assault, alexithymia, behavioral coping responses

Sexual assault (SA; broadly defined as any form of nonconsensual sexual contact) remains at epidemic levels on college campuses in the United States (Abbey et al., 2005), with estimates showing that up to 75% of college women have experienced SA (Abbey et al., 2005; Muehlenhard et al., 2017). SA is considered a potentially traumatic event strongly associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Kessler et al., 2017). Individuals vary in their psychological responses to trauma, and not all of those who experience SA go on to have PTSD (Kessler et al., 2017). Therefore, understanding the characteristics of women’s responses to SA that incur risk for PTSD is considered critical for targeting intervention for those who will experience PTSD and for identifying factors to mitigate that maintain PTSD (Feldner et al., 2007). Importantly, no matter the response, perpetrators are always to blame for SA (Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act, 2013). There is a myriad of factors that can influence how a woman behaviorally responds during a SA (e.g., being in shock, relationship with the perpetrator, whether the perpetrator threatened violence or had a weapon). None of these factors is the woman’s fault. This study aimed to identify aspects of behavioral responses during SA that may help to identify those at risk for PTSD not to determine why women had different reactions or behavioral responses or factors contributing to their engagement in these responses.

Two potential factors that might be associated with women’s psychological outcomes following SA are their behavioral coping responses during SA (Cook & Messman-Moore, 2018; Rizvi et al., 2008). and alexithymia (Frewen et al., 2008, 2012), defined as difficulty with identifying, labeling, and describing one’s emotions. Peritraumatic reactions (i.e., emotional and behavioral reactions during a traumatic event) such as peritraumatic dissociation (Thompson-Hollands et al., 2017) are important predictors of subsequent PTSD among women who experienced SA (Massazza et al., 2021; Ozer et al., 2003). However, the role of peritraumatic behaviors, particularly women’s behavioral responses during SA (Norris et al., 2018), in PTSD has not been widely studied. The behavioral responses one makes during an SA (e.g., dissociating, fighting) may influence how they process the SA (e.g., develop thoughts such as “I cannot protect myself”), that could in turn contribute to PTSD symptoms. Research consistently finds an association between alexithymia and PTSD (Frewen et al., 2008, 2012). Those with greater alexithymia may have difficulty processing why they responded in certain ways during SA, rendering the relationship between behavioral responses and PTSD stronger for those with alexithymia. This study examined associations between behavioral responses and PTSD symptoms and the moderating role of alexithymia.

Behavioral Coping Responses During Sexual Assault

Women’s behavioral responses during SA, also referred to as behavioral responses to threat (Anderson & Cahill, 2015) encompass both verbal (e.g., screaming) and nonverbal (e.g., pulling away) responses, and can be planned (e.g., distracting the perpetrator), unplanned (e.g., crying) and/or elicited involuntarily (e.g., freezing, dissociating, waiting for help). Behavioral responses during SA may refer to a singular response (e.g., kicking) or a series of responses (e.g., pleading, fighting, dissociating). Anderson and Cahill (2015) assert that these behaviors are all responses elicited by a SA and may be automatic and not be planned, or elicited by the women’s perception of the threat.

The literature on behavioral responses to SA is muddled by inconsistent terminology and a lack of a comprehensive definition that encompasses the full range of potential behavioral responses to SA. Researchers agree that no measure or construct will likely ever capture the full range of behavioral coping responses an individual may have during SA. Some researchers have examined behavioral responses on the dimensions of physicality (physical or nonphysical) and forcefulness (forceful or not forceful; See Anderson & Cavill, 2015 for review). However, Anderson and Cahill (2015) argue against such orthogonal perspectives on behavioral responses to threat and suggest a continuous approach. Thus far, the Behavioral Response Questionnaire (BRQ; Macy et al., 2006; Nurius et al., 2000) is considered the most commonly used measure of behavioral coping responses to SA and to incorporate a substantial range of potential responses (Anderson & Cavill, 2015). Factor analysis of the BRQ yielded three broad categories of responses that researchers commonly use (Anderson & Cahill, 2015): assertive, diplomatic, and immobilized (Nurius et al., 2000). As these categories were derived through factor analysis, the BRQ is viewed as the most empirically supported measure of behavioral coping responses during SA. Importantly, these responses are not mutually exclusive. For example, an individual may exhibit a mix of assertive, immobilized, and diplomatic responses during SA.

Assertive responses, also referred to as forceful, direct, or active responses (Davis et al., 2004; Testa et al., 2006), encompass verbal and physical responses such as yelling, attacking the assailant, and running away. On the dimensions of physicality and forcefulness, these responses are often categorized as forceful and can be physical (e.g., hitting) and/or verbal (e.g., yelling) behaviors. Assertive responses have been associated with less severe SA (Clay-Warner, 2002; Ullman, 1997). Diplomatic responses, also referred to as indirect, nonforceful, (Norris et al., 2018), or polite (Davis et al., 2004), include responses that may attempt in a less direct way (e.g., changing the subject, joking) to preserve the safety and protect against the perpetrator while also avoiding emotionally or socially hurting or embarrassing the perpetrator in some way (e.g., telling the person politely you are not interested). Individuals are thought to respond diplomatically in ambiguous situations when the degree of threat is unclear, to divert the assailant’s attention, or diffuse the situation (Nathanson, 2010). Some researchers found diplomatic responses are associated with a higher potential for more severe SA (Clay-Warner, 2002) and consider this type of response to be “passive” (Norris et al., 2018). Others found diplomatic responses protective against PTSD and view them as “active” as they involve verbal or physical actions to mitigate harm (Rizvi et al., 2008). Immobilized responses also referred to as passive or freezing responses (Norris et al., 2018) are characterized by a lack of physical or verbal attempts to stop the SA. Individuals often have immobilized responses when they are in shock, too overwhelmed with fear to respond or trying to avoid injury (Nurius & Norris, 1996).

Women vary in their behavioral coping responses during SA (Kaysen et al., 2005) and tend to engage in multiple behavioral responses during the same SA (Clay-Warner, 2002; Kaysen et al., 2005; Ullman, 2007). Approximately one-third of women reported having assertive responses during SA, whereas a large proportion, particularly women who have experienced rape, reported immobilized responses (Kaysen et al., 2005). The Cognitive Mediation Model of Women’s Sexual Decision Making (Norris et al., 2004) holds that cognitive processes and situational factors influence decision-making during a potential sexual situation and decisions are guided hierarchically by a goal. For example, a woman may engage in a diplomatic response (e.g., faking the arrival of others) with the goal of maintaining the relationship and her appraisal that a more assertive response (e.g., screaming) may interfere with that goal. Situational factors (e.g., presence of a weapon) may shift during the SA, causing appraisals (e.g., belief about danger) and subsequent responses (e.g., use of force) to shift. For example, a woman may initially respond diplomatically, then more assertively, and with increasing violence or recognition that escape is not possible, have an immobilized response (Ullman, 2007).

Behavioral Responses During SA and PTSD

PTSD includes intrusive (e.g., unwanted memories, nightmares), cognitive (e.g., self-blame), emotional (e.g., shame), and behavioral (e.g., substance use, avoidance of trauma reminders) symptoms as a result of a potentially traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Social-cognitive (Brewin et al., 1996) and emotional processing (Foa et al., 1989) theories of PTSD broadly hold that symptoms develop and are maintained by disturbances in how the traumatic event is processed and the meaning one makes from their traumatic experience. Maladaptive trauma processing (e.g., distorted beliefs, fragmented memory, emotional avoidance) is thought to contribute to the behavioral and emotional symptoms that characterize PTSD. Meta-analyses on PTSD support these theories and identify several factors associated with the disorder, including prior history of trauma such as childhood SA and whether the SA was rape (Ozer et al., 2003). In their meta-analysis, Ozer et al. found peritraumatic (occurring at the time of trauma) such as peritraumatic dissociation, peritraumatic emotions, and perceived life threat during the trauma as among the strongest predictors of PTSD. In line with social-cognitive theory, these findings suggest that the way an individual behaviorally responds during an SA and their perceptions of the impact of these responses can influence how they process the SA, contributing to PTSD. For example, the negative appraisals women make of their behavioral responses have been found to be significantly and positively associated with PTSD severity, over and above the severity of the assault (Dunmore et al., 2001; Kline et al., 2018). Behavioral responses may be associated with PTSD symptoms via the meaning derived from the responses (e.g., “I have no control over my safety”) and beliefs about the role of responses in the SA (e.g., “I could have done more to prevent this”). Emotions that may be associated with responses (e.g., shame) and behavioral reactions to the thoughts and emotions (e.g., avoidance) may also contribute to and maintain PTSD symptoms. Although theory and research suggest behavioral responses and PTSD symptoms are associated (e.g., Cook & Messman-Moore, 2018; Rizvi et al., 2008), the relationship requires further study.

Albeit limited, past research suggests that self-reported engagement in fewer assertive responses and more immobilized responses are both associated with greater PTSD symptoms. For example, Rizvi et al. (2008) examined behavioral responses among 296 women who experienced rape or physical assault no more than two months prior to entering their study. They found that less assertive and more immobilized responses during rape or physical assault significantly predicted greater PTSD symptoms. Consistent with their findings, studies of behavioral responses during completed rape suggest that those who reported assertive responses were less likely to experience distress (Selkin, 1978), self-blame, and depression (Bart & O’Brien, 1985; Janoff-Bulman, 1979; Meyer & Taylor, 1986). In an examination of the association between voicing nonconsent during rape and PTSD, Cook and Messman-Moore (2018) found that voicing nonconsent was associated with greater PTSD symptoms. Interestingly, they also found that voicing nonconsent was associated with some level of freezing (further highlighting that behavioral coping responses are not mutually exclusive). However, voicing nonconsent is only one type of assertive response. Cook and Messman-Moore (2018) did not examine the association between other assertive responses (e.g., physical resistance, yelling) and PTSD, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Indeed, across each of the studies cited there are two important limitations. None of the studies included women who had experienced attempted rape or SA other than rape (e.g., nonconsensual sexual contact). Understanding the full spectrum of SA with regard to the association between PTSD symptoms and behavioral responses is important because with varying severity of SA (e.g., unwanted fondling, rape with the use of physical force) women may have different behavioral responses. Second, past studies have not examined the full spectrum of women’s behavioral responses including diplomatic responses (e.g., distracting the perpetrator, making excuses to avoid the situation). As most SA occurs by a known assailant (Ullman, 2007) and diplomatic responses may be more common in acquaintance-perpetrated SA (Macy et al., 2006), understanding the association between diplomatic responses and PTSD symptoms is an important and clinically relevant research gap to address. Understanding the relationship between how a woman responded during attempted or completed SA can aid clinicians in both identifying women who may be at greater risk for posttraumatic stress and may benefit from intervention, and also asking relevant questions to women about their responses and how they make meaning of those responses within the context of the SA and their emotional awareness and experience at the time.

Research on related but distinct peritraumatic constructs also shed light on the association between immobilized responses and PTSD. Meta-analyses on retrospective reports indicate that peritraumatic dissociation (Breh & Seidler, 2007; Ozer et al., 2003) is associated with PTSD symptoms. Peritraumatic dissociation refers to a range of complex reactions that disturb the integration of consciousness, memory, emotion, body representation, behavior and motor control and include mild derealization, depersonalization, motor inhibition, and tonic immobility (Hatzimoysis, 2014). Tonic immobility, an unconditioned fear response displayed by humans and animals in response to an inescapable life threat, is considered evolutionarily adaptive and typically involves complete unresponsiveness and motor inhibition (Hatzimoysis, 2014). Peritraumatic dissociative reactions may render an individual less able to actively respond and more likely to have immobile responses. Immobilized responses may be one behavior displayed during peritraumatic dissociation, but an individual may also have an immobile response without peritraumatic dissociation (e.g., when incapacitated). Taken together, research suggests that immobilized responses may be associated with greater PTSD symptoms, but further research is needed.

In contrast to assertive and immobilized responses, no known literature has examined the association between diplomatic responses and PTSD symptoms. The degree of their association may be related to the subjective meaning made of these responses (Dunmore et al., 2001; Kline et al., 2018). Assertive and immobilized responses can more obviously represent active and nonactive responses, respectively (e.g., Norris et al., 2018; Rizvi et al., 2008). There may be less ambiguity for women in how they make meaning of the role of immobilized and assertive responses whereas the role of diplomatic responses in protecting against SA may be less clear. Whether diplomatic responses are associated with PTSD symptoms may depend on how the individual processes their behavioral responses and the meaning they associated with them (Dunmore et al., 2001; Kline et al., 2018). At present, there is limited literature to inform a hypothesis regarding the association between diplomatic responses and PTSD symptoms.

Alexithymia and PTSD

Considering that not all women who experience SA go on to experience PTSD, an important question regarding the association between behavioral responses and PTSD symptoms is for whom different behavioral coping responses predict PTSD symptoms. Thus, the examination of moderators in the relationship between behavioral responses during SA and PTSD symptoms is important. A potential moderator is alexithymia (Bagby et al., 1994), conceptualized as a psychological trait that entails difficulties describing and identifying emotions, challenges distinguishing emotions from physical sensations, and an externally oriented thinking style. Externally oriented thinking refers to an excessive focus on external stimuli rather than on internal emotional experiences. Alexithymia is not a mental health diagnosis, but a trait considered a risk factor for various psychopathological symptoms and poor adjustment (Pinna et al., 2020). Alexithymia is associated with several mental health disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, autism, eating disorders, personality disorders, and traumatic stress-related disorders (Pinna et al., 2020). Meta-analyses consistently find that alexithymia is significantly and positively associated with PTSD (Frewen et al., 2008, 2012) across survivors of SA (Cloitre et al., 2002; O’Brien et al., 2008). Alexithymia may be related to PTSD through its effects on posttraumatic functioning (e.g., emotional processing of trauma; Frewen et al., 2008). Difficulty with accessing emotions during and following SA can render trauma processing difficult for individuals higher in alexithymia and they may be more avoidant of trauma-related cues and dysregulated when faced with reminders (Frewen et al., 2008). Individuals with alexithymia struggle to describe their emotions and may have less opportunity for emotional disclosure following the SA (Frewen et al., 2008), a predictor of trauma recovery (Balderrama-Durbin et al., 2013) that helps individuals engage in adaptive processing.

Along these lines, individuals who report higher levels of alexithymia may struggle to process why they had certain behavioral responses (e.g., processing that they reacted the way they did during the SA because they were shocked) because they cannot access their peritraumatic emotions. Those who had more immobilized responses or less assertive responses may have difficulty understanding why they were unable to respond actively (e.g., understanding they did not respond actively because they were terrified). These individuals may be at greater risk for emotional dysregulation, negative thoughts cognitions (e.g., Thompson-Hollands et al., 2017), and experiential avoidance that characterize PTSD. Women with alexithymia may also have difficulty accessing their feelings during the SA. Therefore, for those with greater alexithymia, the association between greater immobilized responses, fewer assertive responses, and PTSD may be stronger. Directional hypotheses regarding the moderating role of alexithymia in the association between diplomatic responses and PTSD symptoms are difficult due to the limited and mixed literature on diplomatic responses. As described, diplomatic responses could be interpreted (by the survivor and members of their social milieu) as adaptive and active or as maladaptive or ineffective.

Overview of Current Study

There is a dearth of literature examining the range of behavioral coping responses women may employ during SA and their association with PTSD symptoms in women who experience a range of SAs (e.g., nonconsensual sexual contact, attempted SA). Moreover, no known studies have examined moderators within the association between behavioral coping responses during SA and PTSD symptoms. To address these gaps, this study aimed to examine the following hypotheses in a college sample of women who experienced SA since age 18:

Hypothesis 1: Greater endorsement of assertive behavioral responses would be negatively associated with PTSD and greater endorsement of immobilized responses and alexithymia would be significantly positively associated with PTSD.

Hypothesis 2: For women who endorse greater alexithymia, the positive association between immobilized responses and PTSD symptoms and the negative association between assertive responses and PTSD symptoms would be stronger than for women who endorse less alexithymia. No a priori hypotheses regarding the associations between diplomatic responses and PTSD symptoms and the interaction between diplomatic responses and alexithymia were made. These analyses were exploratory because of past mixed findings as to whether diplomatic responses are “active” or “nonactive” responses. Rape (i.e., oral, vaginal, or anal penetration by incapacitation, physical force, or threat of physical force) has been more strongly associated with PTSD than other types of adult SA (i.e., unwanted sexual touching; Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2015). Further, history of childhood SA has been associated with PTSD (Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2015; Ullman et al., 2009). Therefore, history of adult rape and childhood SA were examined as covariates within study analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were undergraduate students recruited from courses at a midsize university in the southeastern United States. Participation was voluntary. This study was based on a subsample of participants from a larger study on alcohol use, emotion regulation, bystander behaviors, and SA. To be eligible for the parent study, participants had to be between 18 and 26 years old and students at the university. Of that sample, participants were included in the current study who: (1) identified as female and (2) endorsed experiencing at least one unwanted sexual experience since age 18 (attempted or completed) on the Sexual Experiences Survey-Short Form Victimization (SES-SF; Koss et al., 2007).

The final sample in the current study included 152 participants who ranged in age from 18 to 24 years old (M = 19.31, SD = 1.14). Nearly half (n = 67) were freshmen (44.1%), 43 (28.3%) were sophomores, 30 were juniors (19.7%), and 12 were seniors (7.9%) at the university. The majority of the sample identified as White (n = 130, 85.5%). Approximately 10% identified as Black or African American (n = 15), 5.3% Asian (n = 8), and 1% as Alaskan Native (n = 1). A minority (n = 11, 7.2%) identified their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino. With regard to current romantic relationship status, 51 (33.6%) were in a steady relationship, 61 (40.1%) were not in any relationship, 24 (15.8%) were in a casual relationship with one person and 13 (8.6%) were in casual relationships with multiple people.

Measures of Independent Variables

Behavioral coping responses during sexual assault.

To assess behavioral coping responses, participants completed a behavioral response scale developed by Macy et al. (2006) based on prior work (Norris et al., 1996; Nurius et al., 2000). The measure includes 23 items that ask respondents to rate the degree to which they engaged in various behavioral coping responses during the SA since age 18 that they identified through the SES-SF. Respondents who endorsed having more than one SA since age 18 were asked to respond based on the most stressful SA. For each item, the respondent indicates on a 5-point Likert scale how much their response was similar to the item on the scale with anchors as follows: 1 (not at all like my response); 2 (a little like my response); 3 (fairly like my response); 4 (quite a bit like my response); and 5 (very much like my response). The measure yields Assertive, Diplomatic, and Immobilized response scales. The Assertive response scale (e.g., “told him clearly and directly that I wanted him to stop,” “Yelled or screamed loud enough for someone to hear me,” “Raised my voice and used strong language”) consists of 11 items and demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current study (α = .87). The Immobilized response scale includes four items (e.g., “I was so overwhelmed that I felt almost paralyzed and was unresponsive to what the person was doing,” “Struggled at first but stopped when I thought it was hopeless,” “Started tearing up or crying.”). The Diplomatic scale includes eight items (e.g., “nicely or apologetically told him I didn’t want to have sex,” “Tried to get the person to do things I was comfortable with like kissing or hugging, but not sex,” “Made an excuse as to why I didn’t want to have sex.”). The Immobilized (α = .79) and Diplomatic (α = .82) scales both demonstrated adequate internal consistency. A mean score was calculated for each participant for each scale. To determine how many participants engaged in each type of response, participants who endorsed a 3 or greater on response were considered to have engaged in the response.

Alexithymia.

The Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Bagby et al., 1994), a 20-item self-report scale using a 5-point Likert Scale, is the most commonly used self-report measure of alexithymia (Kooiman et al., 2002). Total scores are calculated by summing responses to all items. Higher scores reflect more alexithymia (i.e., difficulty identifying, labeling, and describing emotions). The TAS-20 has demonstrated convergent and concurrent validity (Bagby et al., 1994) and test re-test reliability (r = .77 p < .01; Kooiman et al., 2002) and good internal consistency in prior research (α = .91; Bagby et al., 1994) and the current study (α = .84).

History of childhood sexual assault.

The first three items of the Computer-Assisted Maltreatment Inventory (CAMI; DiLillo et al., 2010) was used to assess for childhood SA. Respondents were presented with a description of potential sexual experiences that can occur during childhood and adolescence, including witnessing sexual activity, unwanted touching, and attempted/completed sexual intercourse. Respondents were then asked three yes/no questions to assess if before age 18 any of the sexual experiences happened to them against their will or when they did not want it to happen, involuntarily with an immediate family member/relative, or involuntarily with anyone more than five years older. Based on responses, a dichotomous variable was created to indicate the presence of self-reported childhood SA.

History of sexual assault in adulthood.

To assess for a history of attempted or completed SA after age 18, participants completed the SES-SF (Koss et al., 2007). The SES-SF uses behaviorally specific language to inquire if participants have experienced attempted or completed sexual contact (e.g., fondling) or penetration (i.e., anal, oral, vaginal) by use of different tactics. These include verbal coercion (e.g., telling lies, verbal threats, or making false promises or using verbal pressure), incapacitation (i.e., taking advantage when the participant was “too drunk or out of it” to stop what was happening) or physical force (i.e., threatening physical force or use of physical force). Participants rate how many times they had each experience with each tactic from 0 (never) to 3 (three or more times).

We first used the SES-SF to determine eligibility for participation from the larger sample (i.e., endorsement of any SES-SF item with any tactic counted as SA and warranted inclusion). The SES-SF can be scored in various ways and recently, researchers have examined the validity and consistency among different scoring methods. Littleton and colleagues (2019) examined each tactic and SA experience separately and found fair to moderate agreement between responders’ endorsements on the SES-SF over an approximately two-week period (Ks range from 0.33 to 0.69 depending on tactic and SA experience), with the most consistency in endorsement of rape. In light of these findings and research that suggests rape is most strongly associated with PTSD symptoms (Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2015), we scored the SES-SF to reflect whether the participant had endorsed having experienced completed rape. Completed rape included oral, vaginal, or anal penetration by incapacitation, physical force, or threat of physical force. Participants who endorsed any type of adult SA were included in the current sample, thus we included a dichotomous variable of adult rape based on the SES-SF in our analyses to control for the history of adult rape (compared with other types of adult SA) on outcomes.

Measures of Dependent Variable

Posttraumatic stress disorder.

The past-month Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013) is a self-report measure of PTSD symptoms according to the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Respondents indicate how much they were bothered by each symptom in the past 30 days from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Participants responded based on their most stressful unwanted sexual experience since age 18. A total score is produced by summing all 20 items. Higher scores indicate greater severity. The PCL-5 demonstrated strong internal consistency in the current (α = .96) and previous studies (α = .94; Weathers et al., 2013). The PCL-5 has demonstrated strong test-retest reliability (r = .82), and convergent (rs = .74 to .85) and discriminant (rs = .31 to .60) validity (Weathers et al., 2013).

Procedure

The study was approved by the university’s institutional review board. Participants were recruited via courses that provided course credit through research study participation. Participants completed an online survey through RedCap, a secure web application. A waiver of written consent was used whereby participants were provided with a description of the study and told that their responses to questions indicated agreement. Participants were debriefed at the end of the study and provided with an opportunity to ask questions.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS Version 25.0 (IBM Corp., 2019). Prior to testing study hypotheses, bivariate correlations were examined between all variables of interest (Table 1). All assumptions of regression and moderation were tested and met. To test hypotheses, a regression was conducted whereby all behavioral coping response scales were entered with alexithymia, childhood SA and history of rape during adulthood to predict PTSD. The behavioral response scales were included in the same rather than in separate models to account for shared variance between them and because they were correlated, indicating that participants endorsed multiple responses. Next, the SPSS Macro PROCESS (Hayes, 2012) was used to develop moderation models specifying linear interactions between the behavioral response type and alexithymia. All predictors were mean-centered to form the products when estimating the moderated path. For significant interaction terms, PROCESS modeled conditional effects of the predictor (simple slopes) at the mean, one below the mean (−1 SD), and one above the mean ( + 1 SD) for the moderator. Three regression models were developed to test for moderation with all variables of interests and an interaction term including one of the behavioral response types and alexithymia. A model with all three interaction terms was not included due to limited power.

Table 1.

Correlations Between Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, Behavioral Coping Responses, and Alexithymia

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PCL | - | .27** | .59*** | .21* | .33** | .32** | .29** | 15.84 | 16.50 |

| 2. Assertive | - | .35** | .48*** | −.04 | .16 | .14 | 1.53 | .72 | |

| 3. Immobilized | - | .29** | −.09 | .31** | .25** | 2.02 | 1.08 | ||

| 4. Diplomatic | - | −.01 | .06 | .07 | 2.34 | .95 | |||

| 5. Alexithymia | - | .02 | −.01 | 41.68 | 9.04 | ||||

| 6. Rape | - | .14 | |||||||

| 7. Childhood SA | - |

Notes. Alexithymia = Toronto Alexithymia Scale; PCL = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5; Rape = endorsed history of experiencing completed rape; SA = Sexual assault.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Results

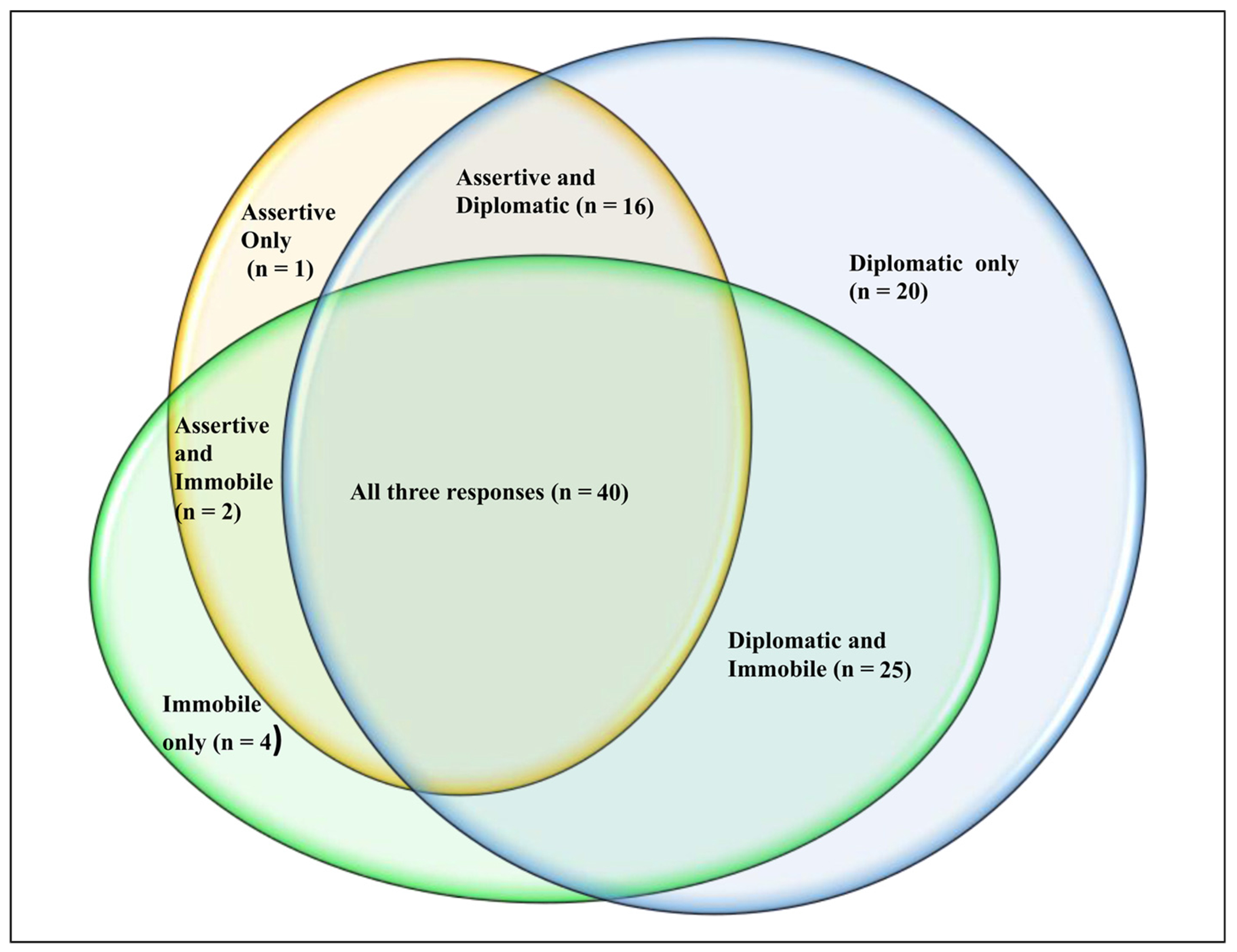

According to the SES-SF, rape (n = 73, 48%) was the most common adult SA reported by participants, followed by unwanted sexual contact (n = 29, 19.1%), rape by coercion (n = 17, 11.2%), attempted rape by coercion (n = 17, 11.2%), and attempted rape (n = 16, 10.5%). Of the behavioral coping responses endorsed, 101 (66.4%) participants reported at least one diplomatic response, 71 (46.7%) at least one immobilized response, and 59 (38.8%) at least one assertive response. Regarding engagement in multiple behavioral responses, 40 (26.3%) participants reported at least one of each response, 25 (16.4%) reported engaging in diplomatic and immobilized responses but no assertive responses, 16 (10.5%) reported engaging in diplomatic and assertive responses and no immobilized responses, and 2 (1.3%) reported engaging in immobilized and assertive responses but no diplomatic responses. See Figure 1 for a Venn Diagram of the endorsement of multiple responses. Fifty-two participants (34.2%) reported childhood SA. Bivariate correlations indicated strong positive associations between PCL-5 scores and immobilized responses (r = .59, p < .001) and moderate positive associations with alexithymia, history of childhood SA, assertive responses, and whether the SA in adulthood was rape (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram of participants’ endorsement of behavioral responses.

Aim 1: Multivariate Model Testing Unique Effects of Behavioral Coping Responses

The regression analysis with all three behavioral responses, alexithymia, history of childhood SA, and whether the SA was rape was significant R2 = 0.49, F(6, 114) = 19.14, p < .001. Immobilized responses (b = 0.52, p < .001), alexithymia (b = 0.34, p < .001), and history of childhood SA (b = 0.18, p = .01) were significantly positively associated with PTSD. The associations between Assertive (b = 0.001 p = .99) and Diplomatic (b = 0.05, p = .54) responses with PTSD were not significant.

Aim 2: Moderation Analyses

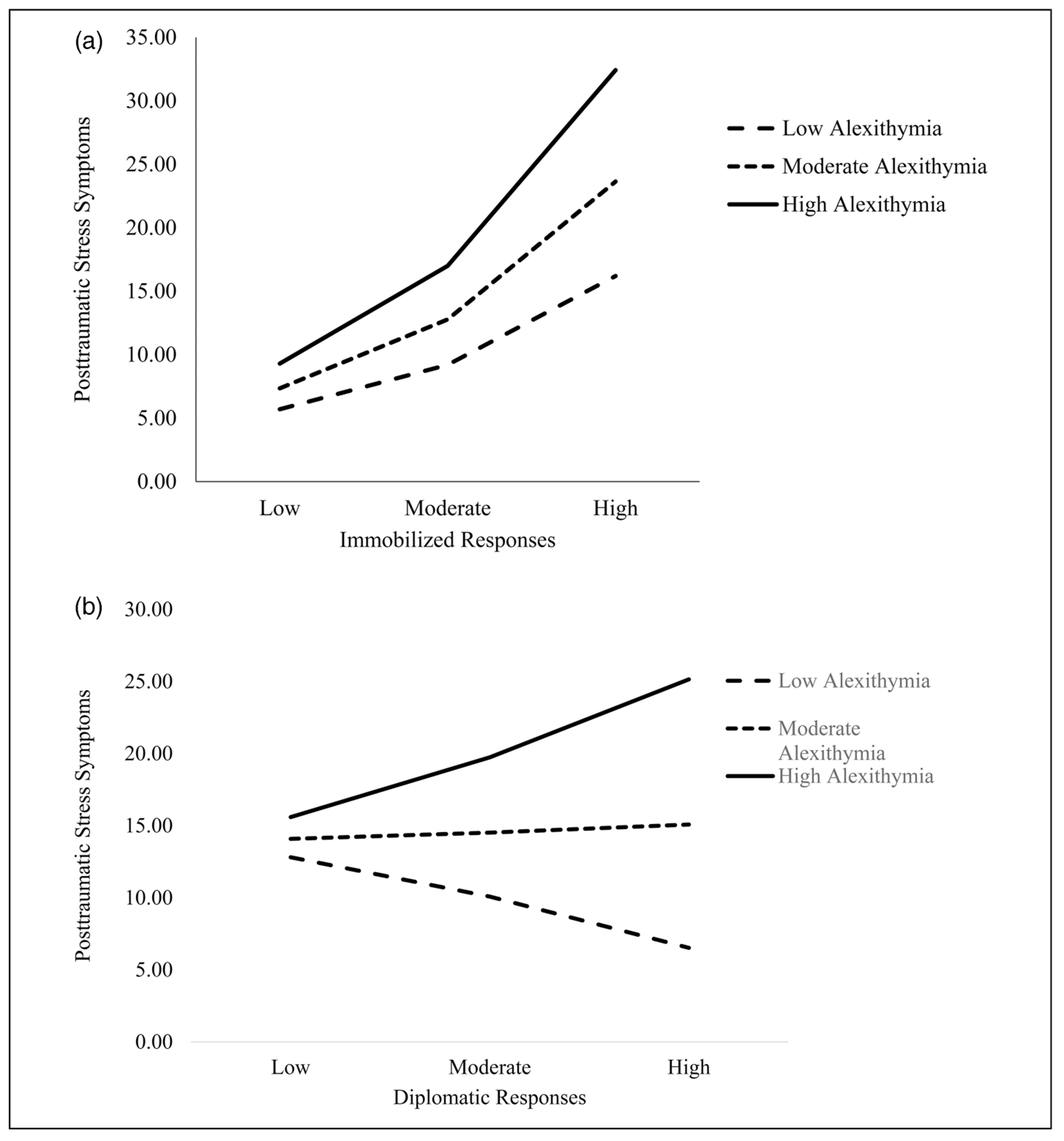

Three multiple regressions were conducted each with childhood SA history, rape, all three behavioral responses, alexithymia, and the interaction between alexithymia and one behavioral response type. In the multiple regression that included the interaction between immobilized responses and alexithymia, the interaction emerged as a significant predictor of PTSD (b = 0.32, p = .002, SE = 0.10; See Table 2). Simple slopes (Figure 2a) indicated that the association between immobilized responses and PTSD was stronger for those higher versus those lower in alexithymia. In the multiple regression that included the interaction between diplomatic responses and alexithymia, the interaction was a significant predictor of PTSD (b = 0.39, p = .002, SE = 0.12; see Table 2). Simple slopes (Figure 2b) indicated that the association between diplomatic response and PTSD was significant only for those at the highest level of alexithymia. Finally, in the multiple regression that included the interaction between assertive responses and alexithymia, the interaction was not significant (b = 0.21, p = .22, SE = 0.17; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Alexithymia as a Moderator in the Associations Between Behavioral Responses and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

| 95% Confidence Interval for b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | b | SE(B) | t | P | Lower bound | Upper bound |

| Assertive | ||||||

| Assertive (centered) | 0.24 | 1.69 | 0.14 | .09 | −12.96 | 0.91 |

| Alexithymia (centered) | 0.58 | 0.12 | 5.10 | <.001 | 0.35 | 0.81 |

| Assertive × Alexithymia | 0.21 | 0.17 | 1.24 | .22 | −0.13 | 0.54 |

| Rape | 3.92 | 2.13 | 1.84 | .07 | −0.31 | 8.15 |

| Childhood SA | 5.91 | 2.14 | 2.77 | .007 | 1.68 | 10.15 |

| Immobilized | 7.08 | 1.08 | 6.53 | <.001 | 4.93 | 9.23 |

| Diplomatic | 0.91 | 1.23 | 0.74 | .46 | −1.53 | 3.35 |

| Diplomatic | ||||||

| Diplomatic (centered) | 0.70 | 1.18 | 0.59 | .56 | −1.64 | 3.03 |

| Alexithymia (centered) | 0.59 | 0.11 | 5.32 | <.001 | 0.37 | 0.81 |

| Diplomatic × Alexithymia | 0.39 | 0.12 | 3.23 | .002 | 0.15 | 0.64 |

| Rape | 3.59 | 2.05 | 1.75 | .09 | −0.48 | 7.65 |

| Childhood SA | 5.58 | 2.04 | 2.74 | .007 | 1.54 | 9.64 |

| Assertive | 0.83 | 1.64 | 0.51 | .61 | −2.42 | 4.08 |

| Immobilized | 7.07 | 1.03 | 6.84 | <.001 | 5.02 | 9.12 |

| Immobilized | ||||||

| Immobilized (centered) | 7.45 | 1.04 | 7.20 | <.001 | 5.40 | 9.51 |

| Alexithymia (centered) | 0.54 | 0.11 | 4.80 | <.001 | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Immobile × alexithymia | 0.32 | 0.10 | 3.15 | .002 | 0.12 | 0.53 |

| Rape | 4.16 | 2.06 | 2.02 | .05 | 0.08 | 8.24 |

| Childhood SA | 5.60 | 2.05 | 2.74 | .007 | 1.54 | 9.66 |

| Assertive | −0.31 | 1.63 | −0.19 | .85 | −3.54 | 2.92 |

| Diplomatic | 0.72 | 1.18 | 0.61 | .55 | −1.62 | 3.06 |

Notes. Alexithymia = Toronto Alexithymia Scale; SA = Sexual Assault; Rape = endorsed history of experiencing completed rape.

Figure 2.

(a) Interaction between immobilized responses and alexithymia predicting posttraumatic stress disorder. Note. Low alexithymia = −1 standard deviation; high alexithymia = +1 standard deviation. (b) Interaction between diplomatic responses and alexithymia predicting posttraumatic stress disorder. Note. Low alexithymia = −1 standard deviation; high alexithymia = +1 standard deviation.

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the associations between college women’s behavioral responses during SA and PTSD, and whether these associations were moderated by alexithymia. As expected, when accounting for alexithymia, history of rape as an adult, childhood SA history, and greater endorsement of immobilized responses significantly predicted PTSD. This association was moderated by alexithymia such that at high levels of alexithymia, the association between immobilized responses and PTSD was stronger. Similarly, the interaction between diplomatic responses and alexithymia was significant, indicating that there was a significant positive relationship between diplomatic responses and PTSD but only for those with high levels of alexithymia. In contrast to hypotheses, assertive responses were not significantly associated with PTSD and the relationship was not moderated by alexithymia. Overall, findings indicate that for individuals who have difficulty identifying and labeling emotions, the association between immobilized and diplomatic responses and PTSD is especially strong.

The result that immobilized responses were significantly and strongly positively associated with PTSD provides important information on potential pathways to PTSD (Rizvi et al., 2008). Immobilized responses may represent a link within the association between peritraumatic emotional distress, distorted cognitive appraisals, and PTSD. Peritraumatic distress (e.g., panic or dissociation) may render someone unable to respond “assertively” and more likely to become immobilized (e.g., Stoner et al., 2007). In turn, individuals who endorsed immobilized responses may be more likely to engage in distorted self-blame (Meyer & Taylor, 1986) and negative self-views (Thompson-Hollands et al., 2017), which is found to predict the onset and maintenance of PTSD (e.g., Kline et al., 2018).

Beyond the intrapersonal processes that may contribute to PTSD, a trauma survivor’s socio-interpersonal context also plays a role in PTSD (Maercker & Horn, 2013) and women’s behavioral responses may influence their interpersonal interactions. Individuals who report immobilized responses during SA may experience more negative reactions from others such as victim blaming (Davies et al., 2008), and negative social reactions are consistently associated with PTSD (Wagner et al., 2016). These intra- and interpersonal pathways likely influence each other (e.g., a person who incurs blame from others may engage in more self-blame) and collectively increase the risk for PTSD.

No a priori hypotheses were made on the associations between diplomatic responses and PTSD because of the dearth of literature on diplomatic responses. Our study suggests that diplomatic responses were only significantly associated with PTSD severity at high levels of alexithymia. The result that at higher levels of alexithymia, there was an association or stronger association between both immobilized and diplomatic responses and PTSD makes sense in light of the potential that the meaning one ascribes to behavioral responses may predict their posttraumatic psychopathology. Individuals who struggle to identify, label, and express their emotions may have difficulty processing the meaning of the SA as it is occurring and, following the SA, why they responded in the ways that they did (e.g., Frewen et al., 2012), increasing their likelihood of experiencing PTSD. As discussed, diplomatic responses may be particularly difficult to interpret in that they may be considered “active” or “immobile/passive” attempts at mitigating SA. Those with greater alexithymia may have more difficulty understanding why they engaged in diplomatic responses and may be more prone to view these responses negatively. It is interesting that there was no significant association between diplomatic responses and PTSD symptoms for those endorsing lower levels of alexithymia. This suggests that for those who have a better ability to understand and process feelings diplomatic responses may not be associated with traumatic stress, perhaps because the individual has more understanding of the reasons why they had diplomatic responses.

Findings are also interesting with regard to research on the association between emotions and behavioral responses during SA. Research suggests anger may mobilize women into action during SA whereas sadness may be associated with diplomatic responses (Jouriles et al., 2014; Nurius et al., 2000). Individuals with greater alexithymia may struggle to express anger, an emotion that could be associated with more assertive responses by emboldening them to respond to the threat. Therefore, at higher levels of alexithymia, diplomatic responses may be associated with PTSD via a lack of anger response.

Findings have important clinical implications for psychotherapy and healthcare professionals interacting with women following SA. Results suggest that those who report more immobilized responses and exhibit more difficulty identifying, labeling, and expressing emotion may be at increased risk for PTSD. Brief interventions that provide psychoeducation and corrective information to normalize women’s responses to SA, reduce self-blame, and facilitate the processing of emotions may be beneficial following SA, particularly for women who endorsed immobilized responses, and high alexithymia and diplomatic responses. Existing trauma-focused interventions that aim to facilitate the processing of the traumatic event such as Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy both focus on accessing nuanced memories of the assault and helping clients understand their role in the assault. These treatments may benefit from fine-tuned emphasis on the individual’s perception of the responses they engaged in during SA. Helping women identify and label their emotions, a current feature in trauma-focused therapies, may be particularly helpful for women who have greater alexithymia.

Findings from this study can also be used to inform educational interventions for formal support (e.g., healthcare workers, law enforcement, college campus staff) and informal supports (e.g., loved ones) of those who experience SA on ways to best respond to disclosure of SA. Those who may be privy to SA disclosure should be educated on the range of behavioral responses that women engage in during SA. They should inform women who disclose that they had an immobilized or diplomatic response during SA that these responses are common, normal and do not indicate that they are responsible for the SA.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several strengths, including the use of a sample exposed to SA. This is also one of the first known studies to examine the associations between a range of behavioral responses and PTSD, and examine alexithymia as a moderator of these associations. Several limitations should be noted. This study relied on participants’ retrospective reports and was correlational. Having PTSD may render individuals more likely to report engaging in certain behavioral responses such as immobilized responses and/or engaging in immobilized responses may increase the risk for PTSD. The temporal sequencing of behavioral responses was also not collected. Women’s engagement in multiple behavioral coping responses and the order in which they responded in each way during the SA may have implications for PTSD (Norris et al., 2018). In future research, measures should assess for the nuanced sequencing of behavioral responses during the SA. Data on the participant’s relationship with the perpetrator was also not collected. Past research identifies that women’s relationships with their perpetrators can influence the behavioral coping responses used during SA (Koss et al., 1988) and the likelihood of PTSD (Feinstein et al., 2011). Other factors are known to be associated with behavioral coping responses and PTSD such as fear of rejection, and alcohol consumption should be examined in future studies (Ullman, 2007).

The study is also limited by some of the measures used. We used one variable based on the SES-SF to capture whether the participants had experienced an adult rape or not, which limits a more nuanced understanding of associations between different SAs and behavioral responses. This scoring method was chosen to be parsimonious in the number of variables included in our models in order to have sufficient power to detect interactions. Future research with larger sample sizes should further investigate the relationship between behavioral responses and SA by tactic and experience. Similarly, data on childhood SA history was limited by the use of a brief self-report measure that detected the presence of childhood SA, but did not collect detailed information about childhood SA, such as type (e.g., unwanted sexual contact, rape), age of onset, or frequency. Future researchers should use the full CAMI to include an assessment of the severity of childhood SA. Although considered a valid and reliable measure of PTSD, the PCL-5 may pick up on general distress rather than only trauma-specific symptoms which may blur the interpretation of current findings. The measure of behavioral responses used in this study captures a greater range of responses than previous literature, however, there is poor data on the measure’s test re-test reliability and it may still not capture the full spectrum of a woman’s potential responses during SA (e.g., the measure does not explicitly assess tonic immobility). Specifically, 44 participants endorsed a 1 or 2 on all scales, suggesting that they did not engage in any response. This finding points to the possibility that certain responses are not assessed with this measure and future research is needed to test this measure.

Although a strength of the study is that all participants had SA histories, constituting a high-risk population for psychopathology and revictimization (de Haas et al., 2012), the sample is limited to women who were enrolled at a university and were predominantly White. Data on participant sexual orientation, religion, and the gender of the perpetrator was also not collected. These factors and their intersectionality can influence behavioral responses used during SA, alexithymia, and PTSD (Richardson & Taylor, 2009). For example, Richardson and Taylor (2009) found that women of color were more likely to experience discrimination based on gender and race simultaneously and to endorse concerns that responding actively could reinforce racial stereotypes. Gender, sexual orientation, race, culture, and cultural beliefs about SA should be considered in future research (Richardson & Taylor, 2009).

Results from the current study add to the literature on the role of peritraumatic factors in PTSD by elucidating that women who endorsed immobilized responses during SA may be at a greater likelihood of experiencing PTSD. For women who exhibit greater alexithymia, the association between immobilized responses during SA and PTSD was stronger and an association between diplomatic responses and PTSD emerged. Women who experience SA victimization are never to blame for the SA and perpetrators hold sole responsibility. The purpose of this study was not to suggest one behavioral response is superior to another or blame individuals for their behavioral responses. Rather, this study aimed to identify factors that can inform intervention to support the psychological well-being and safety of women. Clinically, these findings lend support to the importance of focusing on the identification and expression of emotion in trauma-focused treatments, particularly emotions related to behavioral responses used during the SA. Future research should examine the directionality of associations between immobilized responses, alexithymia, and PTSD and mechanisms within these associations such as cognitive distortions (e.g., self-blame).

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grant numbers 430549, 2U54DA016511-16, K23DA042935, and 1K23AA028055-01A1).

Biographies

Author Biographies

Naomi Ennis, PhD, is the regional clinical and training lead for the Ontario Structured Psychotherapy Program in the Mississauga, Halton, and Brampton regions of Ontario. She was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Medical University of South Carolina. Her research focuses on interpersonal risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder, and enhancing methods for accessing evidence-based trauma-focused treatment.

Alyssa A. Rheingold, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and tenured Professor within the National Crime Victim’s Research and Treatment Center (NCVC) Division at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Dr. Rheingold’s overall research interests include examining the impact of victimization and trauma on a range of health outcomes and evaluating prevention and intervention strategies to promote post-trauma resiliency.

Heidi M. Zinzow is a Professor and Licensed Clinical Psychologist at Clemson University. Her research investigates risk factors associated with the development of psychological symptoms among trauma victims, including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and substance use. Her research also focuses on the development and evaluation of clinical interventions and prevention programs for trauma, including sexual violence, interpersonal violence, combat, and the loss of a loved one to homicide.

Martie P. Thompson, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Psychology at Clemson University. Her research focuses on risk factors and consequences of violence, as well as risk factors for suicidal behavior.

Amanda K. Gilmore, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy and Behavioral Sciences and the Mark Chaffin Center of Healthy Development in the School of Public Health at Georgia State University. Her research focuses on the prevention of alcohol use and sexual assault, as well as secondary prevention of substance use and mental health symptoms after sexual assault.

Dean Kilpatrick is a Distinguished University Professor and senior investigator within the National Crime Victim’s Research and Treatment Center (NCVC) Division at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). His primary research interests include measuring the prevalence of sexual violence, other violent crimes, mass violence, and other types of potentially traumatic events, as well as assessing PTSD and other mental health impacts of such events.

Christine K. Hahn, PhD, is a Research Assistant Professor at the National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center (NCVRTC) at the Medical University of South Carolina. Dr. Hahn conducts research focused on the treatment of substance use and traumatic stress following recent exposure to interpersonal violence. She also investigates the role of emotional and behavioral regulation on traumatic stress, sexual risk-taking, and substance use among people who have experienced interpersonal violence. Finally, her interests include the intersection of traumatic stress and women’s reproductive health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, & Koss MP (2005). The effects of frame of reference on responses to questions about sexual assault victimization and perpetration. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29(4), 364–373. 10.m1/j.1471-6402.2005.00236.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). (American Psychiatric Association, Ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, & Cahill SP (2015). Behavioral response to threat (BRTT) as a key behavior for sexual assault risk reduction intervention: A critical review. Aggression and violent behavior, 25, 304–313. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.09.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, & Taylor GJ (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia scale—I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(1), 23–32. 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balderrama-Durbin C, Snyder DK, Cigrang J, Talcott GW, Tatum J, Baker M, & Smith Slep AM (2013). Combat disclosure in intimate relationships: Mediating the impact of partner support on posttraumatic stress. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 560–568. 10.1037/a0033412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart P, & O’Brien PH (1985). Stopping rape: Successful survival strategies. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bill 113 S.47. (2013). Violence Against Women Act of 2013. 1st session of the 113th Congress. [Google Scholar]

- Breh DC, & Seidler GH (2007). Is peritraumatic dissociation a risk factor for PTSD? Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8(1), 53–69. 10.1300/J229v08n01_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Dalgleish T, & Joseph S (1996). A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review, 103(4), 670. 10.1037/0033-295X.103.4.670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay-Warner J (2002). Avoiding rape: The effects of protective actions and situational factors on rape outcome. Violence and Victims, 17(6), 691–705. 10.1891/vivi.17.6.691.33723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Koenen KC, Cohen LR, & Han H (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook NK, & Messman-Moore TL (2018). I said no: The impact of voicing non-consent on women’s perceptions of and responses to rape. Violence Against Women, 24(5), 507–527. 10.1177/1077801217708059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M, Rogers P, & Bates J-A (2008). Blame toward male rape victims in a hypothetical sexual assault as a function of victim sexuality and degree of resistance. Journal of Homosexuality, 55(3), 533–544. 10.1080/00918360802345339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, George WH, & Norris J (2004). Women’s responses to unwanted sexual advances: The role of alcohol and inhibition conflict. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(4), 333–343. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00150.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Haas S, van Berlo W, Bakker F, & Vanwesenbeeck I (2012). Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence in the Netherlands, the risk of revictimization and pregnancy: Results from a national population survey. Violence and Victims, 27(4), 592–608. 10.1891/0886-6708.27.4.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Hayes-Skelton SA, Fortier MA, Perry AR, Evans SE, Moore TLM, & Fauchier A (2010). Development and initial psychometric properties of the Computer Assisted Maltreatment Inventory (CAMI): A comprehensive self-report measure of child maltreatment history. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(5), 305–317. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunmore E, Clark DM, & Ehlers A (2001). A prospective investigation of the role of cognitive factors in persistent posttraumatic stress disorder after physical or sexual assault. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 39(9), 1063–1084. 10.1016/S0005-7967(00)00088-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Humphreys KL, Bovin MJ, Marx BP, & Resick PA (2011). Victim-offender relationship status moderates the relationships of peritraumatic emotional responses, active resistance, and posttraumatic stress symptomatology in female rape survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(2), 192–200. 10.1037/a0021652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Monson CM, & Friedman MJ (2007). A critical analysis of approaches to targeted PTSD prevention: Current status and theoretically derived future directions. Behavior Modification, 31(1), 80–116. 10.1177/0145445506295057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Steketee G, & Rothbaum BO (1989). Behavioral/cognitive conceptualizations of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy, 20(2), 155–176. 10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80067-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Dozois DJA, Neufeld RWJ, & Lanius RA (2008). Meta-analysis of alexithymia in posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(2), 243–246. 10.1002/jts.20320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Dozois DJA, Neufeld RWJ, & Lanius RA (2012). Disturbances of emotional awareness and expression in posttraumatic stress disorder: Meta-mood, emotion regulation, mindfulness, and interference of emotional expressiveness. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(2), 152. 10.1037/a0023114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzimoysis A. (2014). Passive fear. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 613–623. 10.1007/s11097-014-9353-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0) [computer software]. [Google Scholar]

- Janoff-Bulman R. (1979). Characterological versus behavioral self-blame: Inquiries into depression and rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1798. 10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouriles EN, Simpson Rowe L, McDonald R, & Kleinsasser AL (2014). Women’s expression of anger in response to unwanted sexual advances: Associations with sexual victimization. Psychology of Violence, 4(2), 170–183. 10.1037/a0033191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Morris MK, Rizvi SL, & Resick PA (2005). Peritraumatic responses and their relationship to perceptions of threat in female crime victims. Violence Against Women, 11(12), 1515–1535. 10.1177/1077801205280931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Cardoso G, & Ferry F (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1–16. 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline NK, Berke DS, Rhodes CA, Steenkamp MM, & Litz BT (2018). Self-blame and PTSD following sexual assault: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(5–6), NP3153–NP3168. 10.1177/0886260518770652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman CG, Spinhoven P, & Trijsburg RW (2002). The assessment of alexithymia: A critical review of the literature and a psychometric study of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(6), 1083–1090. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00348-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, & White J (2007). Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 357–370. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Dinero TE, Seibel CA, & Cox SL (1988). Stranger and acquaintance rape: Are there differences in the victim’s experience?. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 12(1), 1–24. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1988.tb00924.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Layh M, Rudolph K, & Haney L (2019). Evaluation of the Sexual Experiences Survey-Revised as a screening measure for sexual assault victimization among college students. Psychology of Violence, 9(5), 555–563. 10.1037/vio0000191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macy RJ, Nurius PS, & Norris J (2006). Responding in their best interests: Contextualizing women’s coping with acquaintance sexual aggression. Violence Against Women, 12(5), 478–500. 10.1177/1077801206288104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maercker A, & Horn AB (2013). A socio-interpersonal perspective on PTSD: The case for environments and interpersonal processes. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(6), 465–481. 10.1002/cpp.1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massazza A, Joffe H, Hyland P, & Brewin CR (2021). The structure of peritraumatic reactions and their relationship with PTSD among disaster survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(3), 248. 10.1037/abn0000663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer CB, & Taylor SE (1986). Adjustment to rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(6), 1226. 10.1037/0022-3514.50.6.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Peterson ZD, Humphreys TP, & Jozkowski KN (2017). Evaluating the one-in-five statistic: Women’s risk of sexual assault while in college. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 549–576. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1295014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AM (2010). The risk of responding to acquaintance sexual assault: How perceived social costs affect risk appraisals and behavioral responses in college women. (Master’s thesis) Retrieved from https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/649/ [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Masters NT, & Zawacki T (2004). Cognitive mediation of women’s sexual decision making: The influence of alcohol, contextual factors, and background variables. Annual Review of Sex Research, 15(1), 258–296. 10.1080/10532528.2004.10559821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Nurius PS, & Dimeff LA (1996). Through her eyes: Factors affecting women’s perception of and resistance to acquaintance sexual aggression threat. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(1), 123–145. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00668.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Zawacki T, Davis KC, & George WH (2018). The role of psychological barriers in women’s resistance to sexual assault by acquaintances. In Orchowski LM & Gidycz CA (Eds.), Sexual assault risk reduction and resistance (pp. 87–11). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, & Norris J (1996). A cognitive ecological model of women’s response to male sexual coercion in dating. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 8(1–2), 117–139. 10.1300/J056v08n01_09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurius PS, Norris J, Young DS, Graham TL, & Gaylord J (2000). Interpreting and defensively responding to threat: Examining appraisals and coping with acquaintance sexual aggression. Violence and Victims, 15(2), 187–208. 10.1891/0886-6708.15.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien C, Gaher RM, Pope C, & Smiley P (2008). Difficulty identifying feelings predicts the persistence of trauma symptoms in a sample of veterans who experienced military sexual trauma. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(3), 252–255. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318166397d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, & Weiss DS (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Hagene LC, & Ullman SE (2015). Sexual assault-characteristics effects on PTSD and psychosocial mediators: A cluster-analysis approach to sexual assault types. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(2), 162. 10.1037/a0037304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna F, Manchia M, Paribello P, & Carpiniello B (2020). The impact of alexithymia on treatment response in psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 311. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BK, & Taylor J (2009). Sexual harassment at the intersection of race and gender: A theoretical model of the sexual harassment experiences of women of color. Western Journal of Communication, 73(3), 248–272. 10.1080/10570310903082065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Kaysen D, Gutner CA, Griffin MG, & Resick PA (2008). Beyond fear: The role of peritraumatic responses in posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms among female crime victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(6), 853–868. 10.1177/0886260508314851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkin J. (1978). Protecting personal space: Victim and resister reactions to assaultive rape. Journal of Community Psychology, 6(3), 263–268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoner SA, Norris J, George WH, Davis KC, Masters NT, & Hessler DM (2007). Effects of alcohol intoxication and victimization history on women’s sexual assault resistance intentions: The role of secondary cognitive appraisals. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 344–356. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00384.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, & Buddie AM (2006). The role of women’s alcohol consumption in managing sexual intimacy and sexual safety motives. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(5), 665–674. 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Hollands J, Jun JJ, & Sloan DM (2017). The association between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptoms: The mediating role of negative beliefs about the self. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(2), 190–194. 10.1002/jts.22179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (1997). Review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 24(2), 177–204. 10.1177/0093854897024002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE (2007). A 10-year update of “review and critique of empirical studies of rape avoidance”. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(3), 411–429. 10.1177/0093854806297117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Najdowski CJ, & Filipas HH (2009). Child sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use: Predictors of revictimization in adult sexual assault survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 18(4), 367–385. 10.1080/10538710903035263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AC, Monson CM, & Hart TL (2016). Understanding social factors in the context of trauma: Implications for measurement and intervention. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(8), 831–853. 10.1080/10926771.2016.1152341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, & Schnurr PP (2013). The ptsd checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). Www.Ptsd.va.Gov, 10. [Google Scholar]