Abstract

Introduction

This study aimed to evaluate the characteristics and prognostic factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients on maintenance hemodialysis (HD).

Methods

All admitted HD patients who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 from December 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023, were included. Patients with pneumonia were further classified into the mild, moderate, severe, and critical illness. Clinical symptoms, laboratory results, radiologic findings, treatment, and clinical outcomes were collected. Independent risk factors for progression to critical disease and in-hospital mortality were determined by the multivariate regression analysis. The receiver operating characteristic analysis with the area under the curve was used to evaluate the predictive performance of developing critical status and in-hospital mortality.

Results

A total of 182 COVID-19 patients with HD were included, with an average age of the 61.55 years. Out of the total, 84 (46.1%) patients did not have pneumonia and 98 (53.8%) patients had pneumonia. Among patients with pneumonia, 48 (49.0%) had moderate illness, 26 (26.5%) severe illness, and 24 (24.5%) critical illness, respectively. Elder age [HR (95% CI): 1.07 (1.01–1.13), p <0.01], increased levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [1.01 (1.003–1.01), p <0.01], and C-reactive protein (CRP) [1.01 (1.00–1.01), p = 0.04] were risk factors for developing critical illness. Elder age [1.11 (1.03–1.19), p = 0.01], increased procalcitonin (PCT) [1.07 (1.02–1.12), p = 0.01], and LDH level [1.004 (1–1.01), p = 0.03] were factors associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality.

Conclusion

Age, CRP, PCT, and LDH can be used to predict negative clinical outcomes for HD patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, Pneumonia, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Prognosis, Mortality

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in December 2019 as the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), sparking a global pandemic [1]. Individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are more susceptible to COVID-19 than the general population due to their compromised immune systems and frequent interactions with healthcare professionals [2]. A latest meta-analysis indicated that the incidence of COVID-19 was even higher among CKD patients undergoing dialysis compared to those not on kidney replacement therapy [2]. A systemic review including 3,261 confirmed COVID-19 cases from a pool of 396,062 patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis (HD) reported a COVID-19 incidence of 7.7% in HD patients, surpassing that in the general population [3]. Moreover, individuals with CKD face an elevated risk of severe illness from COVID-19 [4, 5]. The reported COVID-19-related death in dialysis patients ranged from 13% to 50%, varying according to different regions, populations, and follow-up duration [6–11].

To effectively predict disease progression and enhance clinical outcomes for COVID-19 patients on maintenance HD, it is crucial to identify the risk factors. However, there is still limited evidence regarding the characteristics and prognostic factors in HD patients with COVID-19, especially in the context of SARS-CoV-2 variants and sub-lineages. Previous studies have indicated that inflammatory markers including leukocyte counts, lymphocyte percentage, procalcitonin (PCT), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were strongly associated with in-hospital mortality in HD patients [12–14]. Underlying comorbidities and predominant symptoms such as fever, dyspnea, and cough could also imply a negative prognosis for HD patients infected with COVID-19 [14]. In a study involving HD patients with SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.2.2.1 variant, lymphocyte counts were proved to be an important predictive factor for short-term mortality [15]. The SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant BF.7 and BA.5.2 dominated the COVID-19 outbreak in China between January and December 2022 [16]. However, the characteristics and prognosis of HD patients in this latest outbreak have yet to be investigated.

In the current study, our objective was to evaluate the clinical presentation, laboratory findings, and outcomes of COVID-19 patients undergoing HD, especially those with pneumonia during the latest wave of infection. Our aim was to assist clinicians in identifying high-risk factors for mortality and facilitating early intervention.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This retrospective, single-center study was conducted in Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital, China. It included all HD patients admitted who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 from December 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023. The diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed through the direct detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). COVID-19 pneumonia was diagnosed based on typical manifestations observed in lung CT scans, such as bilateral and peripheral ground-glass opacities in the early stage, or an irregular-shaped paving pattern at later stages [17]. NAATs for SARS-CoV-2 and lung CT scans were performed in all patients admitted with findings suggesting COVID-19 disease. HD patients with the positive NAATs for SARS-CoV-2 and/or typical lung CT findings for COVID-19 disease were included in the study. Patients receiving dialysis less than 3 months and <18 years old were excluded from the study. Patients with incomplete baseline data were also excluded.

The study involving human participants adhered to ethical standards set by the institution and the national research committee. It was in accordance with the principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or similar ethical standards. In addition, all patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study. The Ethics Committee of Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital approved the study with the ethical approval number 38,2023.

Data Collection

The demographic and clinical characteristics including gender, age, BMI, smoking history, comorbidity (hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, cerebral bleeding, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), symptoms, radiologic findings, and treatment regimens were retrieved from the electric medical system. Laboratory data mainly including blood routine test, liver and kidney function, CRP, PCT, electrolyte level, D-dimer levels, interleukin-6, parathyroid hormone, and ferritin were collected during hospitalization. Calcium phosphorus product is calculated using corrected serum calcium values. Corrected serum calcium (mmol/L) is determined as follows: corrected serum calcium (mmol/L) = serum total calcium measurement (mmol/L) + (40 – serum albumin measurement) × 0.025 (mmol/L). Laboratory results were collected from fasting blood drawn from the patient between 7 and 8 AM within 24 h of admission. All the parameters were analyzed in our hospital’s clinical laboratory. Blood routine tests were performed using the impedance method with the fully automated hematology analyzer, Sysmex-XN9000, Japan. Blood biochemistry analyses were conducted using the fully automated biochemistry analyzer, Hitachi 7600. Ferritin and parathyroid hormone levels were assessed using the chemiluminescence method with the American Abbott i2000 chemiluminescence immunoassay analyzer. Interleukin-6 and CRP measurements were carried out using the immunonephelometric method, employing the Siemens fully automated protein analyzer BN II System. PCT was quantified using chemiluminescence, employing the Roche Cobas E601 electrochemiluminescence analyzer. Coagulation function was evaluated via light scattering turbidimetry, using the Sysmex CA-620 fully automated coagulation analyzer by Hycel.

All patients were diagnosed according to the Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of COVID-19 by the National Health Commission of China. All individual participants included in the study provided informed consent to participate. COVID-19 severity is categorized into mild, moderate, severe, or critical illness as follows: (1) mild – mild clinical symptoms, but do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging; (2) moderate – fever, cough, and lung CT with pneumonia; (3) severe – respiratory distress (a respiratory rate >30/min, oxygen saturation ≤93% on room air, and/or ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen [PaO2/FiO2] ≤300 mm Hg); (4) critical – have respiratory failure receiving mechanical ventilation, shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction.

Statistical Analysis

The description of categorical variables was presented using frequencies (percentages). Continuous variables that followed a normal or approximately normal distribution were expressed as means ± standard deviations, while other continuous variables were described using medians (lower quartile, upper quartile). We compared the baseline characteristics of COVID-19 patients with and without pneumonia, as well as the baseline characteristics of patients in the pneumonia group who either died or recovered and patients with different disease severity levels (moderate, severe, critical).

Differences between groups were assessed using the t test (for normally or approximately normally distributed continuous variables), the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (for non-normally distributed continuous variables), or the χ2 test (for categorical variables). In patients with pneumonia, a univariate logistic model was used to explore the association between individual factors and death or the development of critical illness. Based on this, in conjunction with clinical knowledge, existing literature evidence, and the data from our study, some risk factors were selected for inclusion in a multivariate logistic model. Variable selection was performed using the stepwise method to identify independent risk factors for the relevant outcomes. Odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were reported for each risk factor. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the discriminative ability of the multivariate model in predicting events. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 software. The significance level for statistical tests in this study was set at α = 0.05, using a two-tailed test.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Infected HD Patients with and without COVID-19 Pneumonia

A total of 182 COVID-19 patients with HD were included in the study. The average observation time is 11 ± 6 days. The average age of the study cohort was 61.55 years, and 119 (65.38%) patients were male. The majority of kidney diseases related to HD were chronic nephritis (25.82%), diabetic nephropathy (35.16%), and hypertensive nephropathy (32.42%). Among the patients, 158 (86.81%) had preexisting hypertension, 76 (41.76%) had coronary heart disease, 36 (19.78%) had a history of cerebral infarction, 6 (3.3%) had a history of cerebral hemorrhage, and 81 (44.51%) had diabetes. Totally 38 (20.88%) patients ever received COVID-19 vaccine. Five (5.1%) patients had a history of cancer, and 10 patients (10.2%) had non-pulmonary infections. The most frequent symptoms reported were fever, cough and phlegm, fatigue, and decreased appetite. Sixty patients (33.0%) received corticosteroids during the course of disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of HD patients with and without COVID-19 pneumonia

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 182) | No pneumonia (N = 84) | Pneumonia (N = 98) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.55±14.24 | 54.9±14.25 | 67.36±11.46 | <0.01 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 119 (65.38) | 55 (65.48) | 64 (65.31) | 0.98 |

| Female | 63 (34.62) | 29 (34.52) | 34 (34.69) | |

| Smoking history | 25 (13.74) | 20 (23.81) | 5 (5.1) | <0.01 |

| Kidney disease | ||||

| Chronic nephritis | 47 (25.82) | 23 (27.38) | 24 (24.49) | 0.66 |

| Diabetes nephropathy | 64 (35.16) | 27 (32.14) | 37 (37.76) | 0.43 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 59 (32.42) | 37 (44.05) | 22 (22.45) | <0.01 |

| Obstructive nephropathy | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 4 (4.08) | 0.06 |

| Vasculitis | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.38) | 0 (0) | 0.12 |

| Lupus nephritis | 4 (2.2) | 2 (2.38) | 2 (2.04) | 0.88 |

| Others | 21 (11.54) | 12 (14.29) | 9 (9.18) | 0.28 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 158 (86.81) | 71 (84.52) | 87 (88.78) | 0.40 |

| Coronary heart disease | 76 (41.76) | 21 (25) | 55 (56.12) | <0.01 |

| Cerebral infarction | 36 (19.78) | 8 (9.52) | 28 (28.57) | <0.01 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 6 (3.3) | 2 (2.38) | 4 (4.08) | 0.52 |

| Diabetes | 81 (44.51) | 31 (36.9) | 50 (51.02) | 0.06 |

| Corticosteroids | 60 (32.97) | 4 (4.76) | 56 (57.14) | <0.01 |

| Symptom | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 8 (4.4) | 8 (9.52) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Fever | 99 (54.4) | 52 (61.9) | 47 (47.96) | 0.06 |

| Low-grade fever (<38°C) | 33 (18.13) | 24 (28.57) | 9 (9.18) | <0.01 |

| Moderate-grade fever (38–39°C) | 52 (28.57) | 25 (29.76) | 27 (27.55) | |

| High-grade fever (39–41°C) | 14 (7.69) | 3 (3.57) | 11 (11.22) | |

| Sore throat | 31 (17.03) | 27 (32.14) | 4 (4.08) | <0.01 |

| Cough/sputum | 135 (74.18) | 60 (71.43) | 75 (76.53) | 0.43 |

| Nasal congestion/runny nose | 26 (14.29) | 26 (30.95) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Headache | 35 (19.23) | 27 (32.14) | 8 (8.16) | <0.01 |

| Muscle/joint pain | 51 (28.02) | 41 (48.81) | 10 (10.2) | <0.01 |

| Fatigue | 101 (55.49) | 54 (64.29) | 47 (47.96) | 0.03 |

| Abdominal pain/diarrhea | 43 (23.63) | 26 (30.95) | 17 (17.35) | 0.03 |

| Decreased sense of smell and taste | 25 (13.74) | 25 (29.76) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| Vomit | 43 (23.63) | 22 (26.19) | 21 (21.43) | 0.45 |

| Decreased appetite | 115 (63.19) | 48 (57.14) | 67 (68.37) | 0.12 |

| Vaccine administration | ||||

| No | 144 (79.12) | 71 (84.52) | 73 (74.49) | 0.10 |

| Yes | 38 (20.88) | 13 (15.48) | 25 (25.51) | |

| Cancer | 8 (4.4) | 3 (3.57) | 5 (5.1) | 0.62 |

| With non-pulmonary infection | 14 (7.69) | 4 (4.76) | 10 (10.2) | 0.17 |

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (percentage) as appropriate.

Comparison was conducted between patients with and without pneumonia.

Among all these patients, 98 (53.85%) had pneumonia. HD patients with pneumonia were found to be older, had a higher proportion of comorbidities with coronary heart disease or stroke, and had a higher proportion of corticosteroid treatment (p <0.05). Conversely, they had a lower rate of smoking history or a primary diagnosis of hypertension nephropathy. Regarding COVID-19-related symptoms, patients without pneumonia had a higher prevalence of asymptomatic, experiencing low-grade fever (<38°C), sore throat, nasal congestion, headache, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, abdominal pain and diarrhea, anosmia, and decreased appetite (Table 1).

Characteristics of Patients with a Different COVID-19 Severity

Among 98 patients with pneumonia, 48 (48.98%) patients had moderate illness, 26 (26.53%) had severe illness, and 24 (24.49%) had critical illness, respectively. Baseline characteristics including age, gender, BMI, smoking history, kidney disease, comorbidities, symptoms, and chest CT features were generally not significantly different except for a lower proportion of hypertension and a more frequent presence of vomiting and non-pulmonary infection in patients with critical diseases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of pneumonia patients with different COVID-19 types

| Characteristics | Critical (N = 24) | Severe (N = 26) | Moderate (N = 48) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71.3±8.58 | 68.56±12.26 | 64.85±11.81 | 0.07 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 18 (75) | 17 (65.38) | 29 (60.42) | 0.47 |

| Female | 6 (25) | 9 (34.62) | 19 (39.58) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.65±1.16 | 23.64±5.04 | 23.1±4.3 | 0.61 |

| Smoking history | 0 (0) | 2 (7.69) | 3 (6.25) | 0.41 |

| Kidney disease | ||||

| Chronic nephritis | 4 (16.67) | 7 (26.92) | 13 (27.08) | 0.59 |

| Diabetes nephropathy | 11 (45.83) | 11 (42.31) | 15 (31.25) | 0.41 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 4 (16.67) | 4 (15.38) | 14 (29.17) | 0.29 |

| Obstructive nephropathy | 1 (4.17) | 1 (3.85) | 2 (4.17) | 1.00 |

| Lupus nephritis | 1 (4.17) | 1 (3.85) | 0 (0) | 0.37 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 2 (8.33) | 1 (3.85) | 2 (4.17) | 0.71 |

| Others | 1 (4.17) | 1 (3.85) | 2 (4.17) | 1.00 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 18 (75) | 23 (88.46) | 46 (95.83) | 0.03 |

| Coronary heart disease | 13 (54.17) | 15 (57.69) | 27 (56.25) | 0.97 |

| Cerebral infarction | 9 (37.5) | 6 (23.08) | 13 (27.08) | 0.50 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 1 (3.85) | 3 (6.25) | 0.45 |

| Diabetes | 14 (58.33) | 16 (61.54) | 20 (41.67) | 0.19 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (4.17) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (4.17) | 0.78 |

| Vaccine administration | 0.10 | |||

| No | 15 (62.5) | 23 (88.46) | 35 (72.92) | |

| Yes | 9 (37.5) | 3 (11.54) | 13 (27.08) | |

| Cancer history | 0 (0) | 1 (3.85) | 4 (8.33) | 0.30 |

| With non-pulmonary infection | 6 (25) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (4.17) | 0.02 |

| Symptom | ||||

| Fever | 15 (62.5) | 9 (34.62) | 23 (47.92) | 0.14 |

| Low-grade fever (<38°C) | 2 (8.33) | 2 (7.69) | 5 (10.42) | 0.97 |

| Moderate-grade fever (38–39°C) | 9 (37.5) | 5 (19.23) | 13 (27.08) | |

| High-grade fever (39–41°C) | 4 (16.67) | 2 (7.69) | 5 (10.42) | |

| Sore throat | 2 (8.33) | 1 (3.85) | 1 (2.08) | 0.45 |

| Cough/sputum | 17 (70.83) | 24 (92.31) | 34 (70.83) | 0.09 |

| Nasal congestion/runny nose | 1 (4.17) | 1 (3.85) | 6 (12.5) | 0.31 |

| Headache | 1 (4.17) | 2 (7.69) | 7 (14.58) | 0.34 |

| Muscle/joint pain | 14 (58.33) | 10 (38.46) | 23 (47.92) | 0.37 |

| Fatigue | 5 (20.83) | 6 (23.08) | 6 (12.5) | 0.45 |

| Abdominal pain/diarrhea | 8 (33.33) | 0 (0) | 13 (27.08) | 0.01 |

| Decreased sense of smell and taste | 17 (70.83) | 17 (65.38) | 33 (68.75) | 0.91 |

| Chest tightness/shortness of breath | 17 (70.83) | 20 (76.92) | 32 (68.09) | 0.73 |

| Nausea | 1 (4.17) | 2 (7.69) | 6 (12.77) | 0.47 |

| Altered mental status | 4 (16.67) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (4.26) | 0.20 |

| Chest CT | 0.37 | |||

| Unilateral involvement | 0 (0) | 1 (3.85) | 0 (0) | |

| Bilateral involvement | 13 (54.17) | 18 (69.23) | 34 (70.83) | |

| Extensive ground-glass opacity with consolidation, linear, or reticular opacity | 10 (41.67) | 5 (19.23) | 12 (25) | |

| Diffuse consolidation with ground-glass opacity | 1 (4.17) | 2 (7.69) | 2 (4.17) | |

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (percentage) as appropriate.

Comparison was conducted among patients with a different severity.

Comparison of laboratory results among patients with a different severity showed that patients with moderate illness tended to have greater levels of oxygen saturation and albumin, while those with severe or critical illnesses had more increased levels of white blood cell count, neutrophil count, interleukin-6, creatine kinase, urea nitrogen, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), CRP, D-dimer, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (Table 3). In terms of treatment, a larger proportion of critical patients received corticosteroid (p = 0.01) and low molecular weight heparin (p = 0.06), meropenem (p = 0.01), and required oxygen support (p <0.01) (Table 3). The in-hospital outcomes showed that majority of patients with moderate and severe illness improved (moderate: 89.58%, severe: 88.46%) whereas 54.17% of critical patients died during hospitalization (Table 3).

Table 3.

Laboratory results, treatment, and clinical outcomes of pneumonia patients with a different severity

| Characteristics | Overall (N = 98) | Critical (N = 24) | Severe (N = 26) | Moderate (N = 48) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory | |||||

| Hemoglobin oxygen saturation, % | 94.2 (90.9, 96.7) | 93.5 (87.5, 97) | 90.85 (87.7, 93) | 94.2 (94.2, 97) | <0.01 |

| Oxygen partial pressure, mm Hg | 86.62±31.72 | 82.67±36.15 | 70.08±25.8 | 103.96±24.73 | <0.01 |

| PCT, ng/mL | 1.32 (0.68, 2.55) | 1.59 (1.02, 8.52) | 1.66 (0.97, 4.91) | 1.32 (0.63, 1.32) | 0.06 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 465 (366.13, 621.7) | 465 (355.43, 744.31) | 465 (465, 964.57) | 465 (317.1, 465) | 0.05 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.38±0.78 | 4.6±0.74 | 4.44±0.96 | 4.25±0.69 | 0.20 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 138.93±4.56 | 141.97±4.53 | 138.07±5.49 | 137.96±3.34 | <0.01 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 1.99±0.29 | 1.95±0.19 | 2.07±0.22 | 1.97±0.36 | 0.30 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 21.83 (16.2, 30) | 25 (18.9, 36) | 23.98 (16.03, 31) | 20.3 (15.9, 28) | 0.19 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 12.2 (7.85, 22.25) | 13 (8.7, 22.5) | 15 (10.7, 32.2) | 10.8 (7.7, 18.4) | 0.23 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 93.32±20.81 | 91.54±26.33 | 95.64±20.89 | 93±17.76 | 0.78 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 168.8±78.2 | 157.33±73.77 | 172.79±76.13 | 172.62±82.37 | 0.71 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 93.95 (60.3, 157) | 121.55 (80.6, 228.6) | 110.15 (58, 149.2) | 80.7 (46.2, 112) | 0.05 |

| Creatinine, umol/L | 718.95 (557, 943.2) | 615.94 (369.72, 921) | 718.89 (438.16, 842) | 759.7 (605.5, 964.3) | 0.24 |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 1.77±0.7 | 1.81±0.74 | 1.69±0.63 | 1.79±0.72 | 0.79 |

| Albumin, g/L | 30.81±5.94 | 28.03±5.14 | 30.88±4.45 | 32.17±6.6 | 0.02 |

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 5.88 (4.18, 8.84) | 8.44 (5.32, 15.02) | 7.74 (4.51, 9.67) | 4.99 (3.88, 6.57) | <0.01 |

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 39.2 (20.83, 68.65) | 70.97 (39.2, 270.8) | 39.2 (8.47, 39.2) | 39.2 (8.6, 39.2) | 0.01 |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/mL | 242.75 (184.2, 332.7) | 242.75 (197.2, 242.75) | 242.75 (240.7, 294) | 242.75 (145.65, 411) | 0.87 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 0.5 (0.37, 0.72) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.5) | 0.5 (0.29, 0.72) | 0.52 (0.44, 0.78) | 0.04 |

| Myocardial creatine kinase, U/L | 12.36±7.52 | 16.45±8.88 | 12.23±7.07 | 9.79±5.67 | <0.01 |

| Uric acid, umol/L | 415.45±162.83 | 472.55±173.33 | 398.47±141.6 | 394.47±164.02 | 0.15 |

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 23.35±11.9 | 29.68±12.83 | 22.73±13.41 | 19.51±8.35 | 0.01 |

| LDH, U/L | 329.35±147.71 | 423.34±155.45 | 347.39±189.23 | 272.59±78.59 | <0.01 |

| Neutrophil count, 109/L | 4.63 (2.97, 7.94) | 7.07 (4.61, 12.31) | 6.65 (3.41, 8.62) | 3.95 (2.72, 5.65) | <0.01 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 2.11 (1.25, 3.14) | 3.91 (2.11, 9.49) | 2.11 (1.08, 3.06) | 2.11 (1.01, 2.11) | <0.01 |

| CRP, mg/L | 64.99 (41.95, 108.51) | 86.24 (61.49, 166.07) | 64.99 (56.13, 127.65) | 59.81 (18.14, 73.11) | <0.01 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 8.74 (5.5, 14.56) | 12.6 (8.74, 29.98) | 9.66 (7.64, 20.59) | 7.23 (4.93, 9.39) | <0.01 |

| Platelet/lymphocyte ratio | 282.98 (193.33, 512.5) | 367.5 (235.53, 609.15) | 344.57 (218.29, 463.16) | 265.96 (178.46, 495.74) | 0.36 |

| Calcium phosphorus product | 3.78±1.31 | 3.96±1.53 | 3.74±1.24 | 3.71±1.25 | 0.74 |

| Treatment | |||||

| Corticosteroids | 56 (57.14) | 20 (83.33) | 15 (57.69) | 21 (43.75) | 0.01 |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 19 (19.39) | 8 (33.33) | 6 (23.08) | 5 (10.42) | 0.06 |

| Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir | 46 (46.94) | 15 (62.5) | 11 (42.31) | 20 (41.67) | 0.21 |

| Antibiotic | 89 (90.82) | 23 (95.83) | 24 (92.31) | 42 (87.5) | 0.49 |

| Meropenem | 51 (52.04) | 18 (75) | 15 (57.69) | 18 (37.5) | 0.01 |

| Cephalosporins | 52 (53.06) | 13 (54.17) | 16 (61.54) | 23 (47.92) | 0.53 |

| Piperacillin | 27 (27.55) | 8 (33.33) | 4 (15.38) | 15 (31.25) | 0.26 |

| Oxygen therapy | |||||

| Nasal cannula | 66 (67.35) | 4 (16.67) | 18 (69.23) | 44 (91.67) | <0.01 |

| High flow | 18 (18.37) | 8 (33.33) | 8 (30.77) | 2 (4.17) | <0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 18 (18.37) | 18 (75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.01 |

| In-hospital outcome | |||||

| Death | 16 (16.33) | 13 (54.17) | 2 (7.69) | 1 (2.08) | <0.01 |

| Improvement | 77 (78.57) | 11 (45.83) | 23 (88.46) | 43 (89.58) | |

| Continue treatment | 3 (3.06) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.85) | 2 (4.17) | |

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (interquartile), or number (percentage) as appropriate.

Characteristics of Hospital Survivors and Non-Survivors

For HD patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, 82 (83.67%) patients survived and 16 (16.33%) died during hospitalization. Non-survivors were older and more likely to have fever, received mechanical ventilation, and increased level of sodium, interleukin-6, uric acid, urea nitrogen, and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio compared with survivors (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of pneumonia patients between in-hospital death and survival

| Characteristics | Non-survivor (N = 16) | Survivor (N = 82) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73.87±8.52 | 66.16±11.58 | 0.02 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 (81.25) | 51 (62.2) | 0.14 |

| Female | 3 (18.75) | 31 (37.8) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 21.08±1.58 | 23.15±4.26 | 0.41 |

| Smoking history | 0 (0) | 5 (6.1) | 0.31 |

| Kidney disease | |||

| Chronic nephritis | 5 (31.25) | 19 (23.17) | 0.49 |

| Diabetes nephropathy | 5 (31.25) | 32 (39.02) | 0.56 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 3 (18.75) | 19 (23.17) | 0.70 |

| Obstructive nephropathy | 1 (6.25) | 3 (3.66) | 0.63 |

| Lupus nephritis | 0 (0) | 2 (2.44) | 0.53 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 2 (12.5) | 3 (3.66) | 0.14 |

| Others | 0 (0) | 4 (4.88) | 0.37 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypertension | 12 (75) | 75 (91.46) | 0.06 |

| Coronary heart disease | 9 (56.25) | 46 (56.1) | 0.99 |

| Cerebral infarction | 4 (25) | 24 (29.27) | 0.73 |

| Cerebral hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 4 (4.88) | 0.37 |

| Diabetes | 10 (62.5) | 40 (48.78) | 0.32 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 (6.25) | 4 (4.88) | 0.82 |

| Vaccine administration | 0.49 | ||

| No | 13 (81.25) | 60 (73.17) | |

| Yes | 3 (18.75) | 22 (26.83) | |

| Cancer history | 0 (0) | 5 (6.49) | 0.29 |

| With non-pulmonary infection | 2 (12.5) | 8 (10.39) | 0.80 |

| Treatment | |||

| Corticosteroids | 12 (75) | 44 (53.66) | 0.11 |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 5 (31.25) | 14 (17.07) | 0.19 |

| Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir | 11 (68.75) | 35 (42.68) | 0.06 |

| Antibiotic | 16 (100) | 73 (89.02) | 0.16 |

| Meropenem | 11 (68.75) | 40 (48.78) | 0.14 |

| Cephalosporins | 8 (50) | 44 (53.66) | 0.79 |

| Piperacillin | 4 (25) | 23 (28.05) | 0.80 |

| Oxygen therapy | |||

| Nasal cannula | 6 (37.5) | 60 (73.17) | 0.01 |

| High flow | 4 (25) | 14 (17.07) | 0.45 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 7 (43.75) | 11 (13.41) | <0.01 |

| Chest CT | |||

| Unilateral involvement | 0 (0) | 1 (1.3) | 0.82 |

| Bilateral involvement | 9 (56.25) | 51 (66.23) | |

| Extensive ground-glass opacity with consolidation, linear, or reticular opacity | 6 (37.5) | 21 (27.27) | |

| Diffuse consolidation with ground-glass opacity | 1 (6.25) | 4 (5.19) | |

| Symptom | |||

| Fever | 12 (75) | 35 (42.68) | 0.02 |

| Low-grade fever (<38°C) | 2 (12.5) | 7 (8.54) | 0.96 |

| Moderate-grade fever (38–39°C) | 7 (43.75) | 20 (24.39) | |

| High-grade fever (39–41°C) | 3 (18.75) | 8 (9.76) | |

| Sore throat | 1 (6.25) | 3 (3.66) | 0.63 |

| Cough/sputum | 14 (87.5) | 61 (74.39) | 0.26 |

| Nasal congestion/runny nose | 1 (6.25) | 7 (8.54) | 0.76 |

| Headache | 1 (6.25) | 9 (10.98) | 0.57 |

| Muscle/joint pain | 8 (50) | 39 (47.56) | 0.86 |

| Fatigue | 3 (18.75) | 14 (17.07) | 0.87 |

| Abdominal pain/diarrhea | 3 (18.75) | 18 (21.95) | 0.78 |

| Decreased sense of smell and taste | 8 (50) | 59 (71.95) | 0.08 |

| Chest tightness/shortness of breath | 10 (62.5) | 59 (72.84) | 0.40 |

| Nausea | 1 (6.25) | 8 (9.88) | 0.65 |

| Altered mental status | 2 (12.5) | 6 (7.41) | 0.50 |

| Severity | |||

| Critical | 13 (81.25) | 11 (13.41) | <0.01 |

| Severe | 2 (12.5) | 24 (29.27) | |

| Moderate | 1 (6.25) | 47 (57.32) | |

| Laboratory | |||

| Hemoglobin oxygen saturation, % | 93 (85.6, 97.9) | 94.2 (92.7, 96.2) | 0.51 |

| Oxygen partial pressure, mm Hg | 92.64±38.99 | 85.09±29.81 | 0.43 |

| PCT, ng/mL | 2.03 (0.8, 9.33) | 1.32 (0.68, 2.33) | 0.19 |

| Ferritin, ng/mL | 465 (326.29, 756.96) | 465 (398.54, 591) | 0.80 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | 4.61±0.94 | 4.34±0.75 | 0.22 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | 142.49±4.07 | 138.25±4.35 | <0.01 |

| Calcium, mmol/L | 2.06±0.26 | 1.98±0.3 | 0.34 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 27 (24.3, 31.5) | 21.4 (15.9, 29.5) | 0.05 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 17.2 (9.5, 21.2) | 12 (7.7, 22.7) | 0.47 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 89±23.21 | 94.19±20.35 | 0.37 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 162.19±78.56 | 170.14±78.56 | 0.71 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 119.6 (79.65, 170.85) | 93.95 (46.7, 149.2) | 0.18 |

| Creatinine, umol/L | 755 (443, 945.76) | 718.89 (566, 943.2) | 0.94 |

| Phosphorus, mmol/L | 1.83±0.71 | 1.76±0.7 | 0.70 |

| Albumin, g/L | 29.69±4.37 | 31.03±6.2 | 0.41 |

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 7.72 (3.93, 12.75) | 5.78 (4.27, 8.64) | 0.24 |

| Interleukin-6, pg/mL | 139.28 (43.49, 369.85) | 39.2 (10.02, 39.2) | <0.01 |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/mL | 242.75 (223.43, 478.25) | 242.75 (177.5, 332.3) | 0.34 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 0.36 (0.29, 0.55) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.74) | 0.08 |

| Myocardial creatine kinase, U/L | 14.43±10.35 | 11.91±6.77 | 0.40 |

| Uric acid, umol/L | 492.49±176.56 | 400.04±156.68 | 0.04 |

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 30.56±13.09 | 21.7±11.08 | 0.01 |

| LDH, U/L | 392.91±157.67 | 316.95±143.43 | 0.06 |

| Neutrophil count, 109/L | 7.01 (2.95, 11.51) | 4.24 (2.97, 7.12) | 0.13 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 3.08 (1.7, 7.35) | 2.11 (1.23, 2.98) | 0.10 |

| CRP, mg/L | 77.71 (44.06, 140.2) | 64.99 (41.95, 98.54) | 0.28 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 13.41 (7.56, 31.03) | 8.74 (5.4, 13.06) | 0.03 |

| Platelet/lymphocyte ratio | 375 (151.67, 629.41) | 278.99 (193.33, 463.16) | 0.47 |

| Calcium phosphorus product | 4.09±1.51 | 3.72±1.27 | 0.30 |

Data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (interquartile), or number (percentage) as appropriate.

Risk Factors and Prediction for Developing Critical Illness in Pneumonia Patients

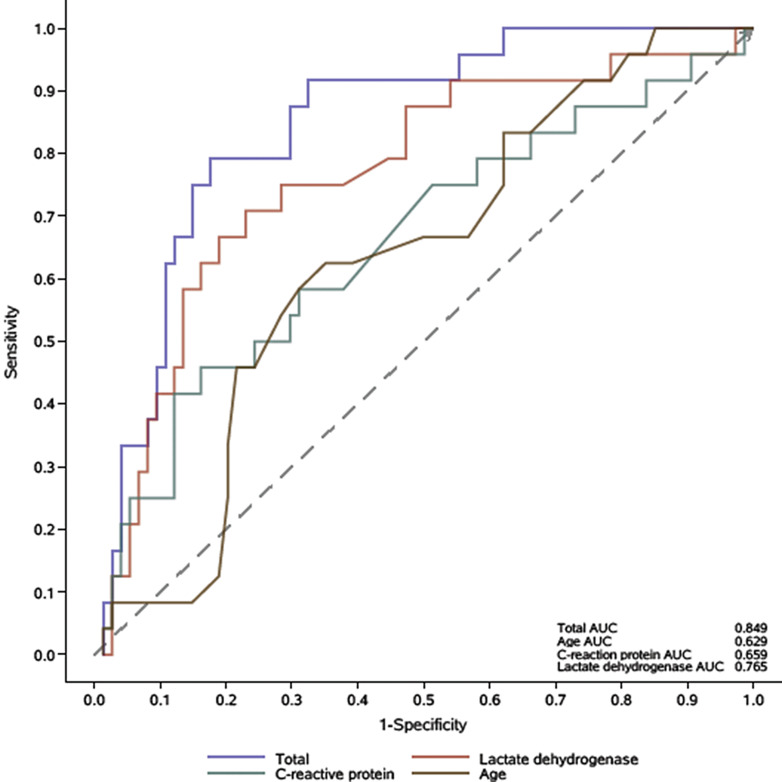

The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that elder age [HR (95% confidence interval): 1.07 (1.01–1.13), p <0.01], increased levels of LDH [1.01 (1.003–1.01), p <0.01], and CRP [1.01 (1.00–1.01), p = 0.04] were independent risk factors for developing critical illness in HD patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (Table 5). The receiver operating characteristic curve showed that the predictive performance of age, LDH, and CRP as reflected by AUC was 0.629, 0.765, and 0.659, respectively. The AUC for integrated factors was 0.849 (Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for developing critical illness in pneumonia patients

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, years | 1.04 (1–1.09) | 0.06 | 1.07 (1.01–1.13) | <0.01 |

| Female | 0.55 (0.19–1.54) | 0.25 | / | / |

| Hypertension | 0.22 (0.06–0.79) | 0.02 | / | / |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.9 (0.36–2.27) | 0.82 | / | / |

| Diabetes | 1.48 (0.58–3.75) | 0.41 | / | / |

| Hemoglobin oxygen saturation | 0.92 (0.84–1) | 0.04 | / | / |

| PCT, ng/mL | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.27 | / | / |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 1 (1–1) | 0.25 | / | / |

| Albumin, g/L | 0.89 (0.82–0.98) | 0.02 | / | / |

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 0.14 | / | / |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/mL | 1 (1–1) | 0.89 | / | / |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 0.3 (0.05–1.64) | 0.16 | / | / |

| LDH, U/L | 1.01 (1–1.01) | <0.01 | 1.01 (1.003–1.01) | <0.01 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1.01 (1–1.01) | 0.02 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.04 |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 1.07 (1.02–1.11) | <0.01 | / | / |

| Calcium phosphorus product | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | 0.43 | / | / |

| Extensive ground-glass opacity with consolidation, linear, or reticular opacity | 2.4 (0.89, 6.45) | 0.08 | / | / |

| Diffuse consolidation with ground-glass opacity | 1.02 (0.1, 9.9) | 0.98 | / | / |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

ROC curve of the multivariate logistic model for being critical. ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

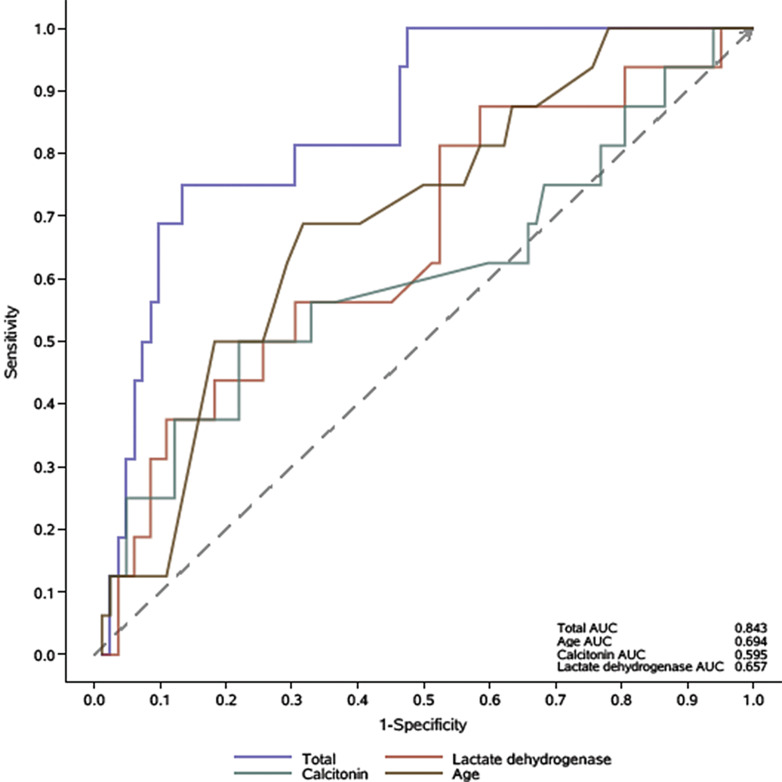

Prognostic Factors and Prediction for In-Hospital Mortality

The multivariate analysis demonstrated that age [1.11 (1.03–1.19), p = 0.01], PCT [1.07 (1.02–1.12), p = 0.01], and LDH level [1.004 (1–1.01), p = 0.03] were three independent factors associated with increased risk of in-hospital mortality (Table 6). The AUC for age, PCT, and LDH was 0.694, 0.595, and 0.657, respectively. The predictive performance of integrated factors was better (AUC: 0.843) (Fig. 2).

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for in-hospital mortality in pneumonia patients

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, years | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 0.02 | 1.11 (1.03–1.19) | 0.01 |

| Female | 0.38 (0.1–1.44) | 0.15 | – | – |

| Hypertension | 0.28 (0.07–1.1) | 0.07 | – | – |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.01 (0.34–2.96) | 0.99 | – | – |

| Diabetes | 1.75 (0.58–5.26) | 0.32 | – | – |

| Hemoglobin oxygen saturation | 0.95 (0.87–1.03) | 0.20 | – | – |

| PCT, ng/mL | 1.04 (1–1.08) | 0.07 | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 0.01 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 1 (1–1) | 0.26 | – | – |

| Albumin, g/L | 0.96 (0.88–1.05) | 0.41 | – | – |

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 1 (0.96–1.04) | 0.99 | – | – |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/mL | 1 (1–1) | 0.07 | – | – |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 0.75 (0.13–4.34) | 0.74 | – | – |

| LDH, U/L | 1 (1–1.01) | 0.07 | 1.004 (1–1.01) | 0.03 |

| CRP, mg/L | 1.01 (1–1.01) | 0.04 | – | – |

| Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio | 1.03 (1–1.07) | 0.06 | – | – |

| Calcium phosphorus product | 1.24 (0.83–1.85) | 0.29 | – | – |

| Extensive ground-glass opacity with consolidation, linear, or reticular opacity | 1.81 (0.57, 5.7) | 0.31 | / | / |

| Diffuse consolidation with ground-glass opacity | 1.58 (0.16, 15.81) | 0.69 | / | / |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve of the multivariate logistic model for in-hospital death. ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Discussion

The current study investigated the clinical characteristics and in-hospital mortality among 182 HD patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 from December 1, 2022, to January 31, 2023. COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in approximately half of the patients, and 8.8% of the entire population did not survive hospitalization. Our findings indicate that age, LDH, and inflammatory markers CRP and PCT were associated with an unfavorable prognosis. Moreover, a combined prediction that incorporates multiple risk factors, rather than a single factor, could more accurately predict the clinical outcome.

COVID-19 infection poses a challenge to HD patients, with certain demographic and clinical manifestations observed in this unique population. Previous observations of dialysis cases with COVID-19 showed that diabetes and hypertensive nephropathy are the predominant kidney diseases, with most patients being over 50 years old [18]. Similarly, in the current study, chronic nephritis, diabetes, and hypertensive nephropathy accounted for 93.4% of the whole population with an average age exceeding 60 years. Over 65% of our patients were male, aligning with prior research suggesting that male sex was associated with an increased risk of contracting COVID-19, and male dialysis patients had double the incidence of COVID-19 compared to females [10, 19]. Regarding the COVID-19-related symptoms, our findings mirror those of previous studies, the most common symptoms upon presentation being fever, cough, sore throat, decreased appetite, and fatigue [19–22]. However, our study noted that these clinical symptoms were more frequently observed in HD patients without pneumonia than in those with pneumonia. This difference could potentially be attributed to immunocompromised condition of these patients [23]. Thus, we suggest that chest CT for pneumonia detection should be conducted for every HD patient, even if they do not display significant symptoms.

Pneumonia emerged as the most common complication in COVID-19 patients and shortness of breath was frequently seen in those afflicted with COVID-19 pneumonia [19, 24]. Previous studies involving the general population infected with the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant revealed that 57–81% of patients experienced mild cases without pneumonia [21, 22]. For dialysis patients infected with COVID-19, the incidence of pneumonia was notably higher than that in the general population, at times reaching a prevalence as high as 72%, although this figure varied across different populations [19]. In our study, over half of the patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia. Among these patients, 51% were classified as having severe or critical conditions, and 16.3% did not survive during their hospitalization. These statistics align with previous reports, which documented that 2.6–70.5% of HD patients with COVID-19 were admitted into the intensive care unit, with associated mortality rates ranging from 42.8% to 100% [8].

Previous literature has identified several demographic and clinical prognostic factors in HD with COVID-19 [18, 25–29]. Advanced age constitutes not only a risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection but also a negative prognostic factor for HD patients with COVID-19 [18]. Our study corroborates these findings, as we identified age as an independent factor for disease progression to critical illness and in-hospital mortality, aligning with previous research [25, 30]. Data from the ERA-EDTA Registry in Europe collecting data of 4,298 patients receiving kidney replacement therapy reported an increased mortality risk among older COVID-19 patients [30]. Especially in those aged over 75 years, the 28-day mortality rate could soar to 31.4% [30]. A recent review comprising 41 studies similarly emphasized the significance of age as a crucial risk factor for dialysis patients [18].

CRP was a prognostic factor for critical progression, while PCT was identified as a risk factor for hospital mortality in our study. Likewise, these inflammatory biomarkers have previously been proved to be associated with the risk of death in COVID-19 [25, 31]. Increased LDH levels are often detected in severe COVID cases, reflecting extensive pulmonary damage [32]. LDH at the time of admission can predict subsequent disease severity of and death among COVID-19 patients [33, 34]. Notably, we discovered that the predictive value for mortality and critical progression improved when these markers were considered in combination rather than in isolation. Our findings therefore suggest a feasible predictive model for HD patients with COVID-19, which may aid physicians in identifying patients at higher risk of poor outcomes and enable to manage disease better.

Previous studies have demonstrated that comorbidities such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, clinical features such as cough, dyspnea, and fever, and laboratory examinations including leucocyte, platelet count, and serum albumin levels may imply a grim prognosis in HD patients with COVID-19 [14]. However, our study did not reveal the impact of these factors on mortality. The heterogeneity of the study population and the varying impact of different SARS-CoV-2 variants may account for the disparities among study results. Our analysis of thoracic imaging results showed that bilateral involvement and extensive ground-glass opacity with consolidation, linear, or reticular opacity were the primary findings on CT scans, consistent with previous reports [35, 36]. Nevertheless, we did not observe differences in imaging findings among patients with different disease severities, which suggests that relying solely on radiographic findings to assess severity and predict disease progression in HD patients with COVID-19 may not be reliable.

There are several limitations of the study. First, this is a retrospective study with a limited sample size. There might be important clinical characteristics that were not included in our analysis. For example, HD-related dialysis vintage, which has previously been demonstrated to be associated with mortality, was not recorded in this study [27]. Second, the long-term effects of COVID-19 on HD patients were not investigated in this study. Further large-scale studies with longer observation time are necessary to validate our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, COVID-19 pneumonia is prevalent in approximately half of patients with HD. Chest CT scans may be a necessity for HD patients, even if these patients do not exhibit noticeable symptoms. Furthermore, elder age and elevated levels of CRP, PCT, and LDH may serve as predictive factors for adverse clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Big Data platform of Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital.

Statement of Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital approved the study with the ethical approval number 38,2023. In addition, all patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the authors.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (Grant No. 2021JJ40297), Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital RENSHU Funding Project (Grant No. RS201801), Young Doctor Fund and Fund for Fostering of the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. BSJJ201806), and Hunan Provincial Health Commission project (Grant No. D202314016355, 202203052969).

Author Contributions

F.Z. and GL.L. wrote the draft of paper; J.Y., YY.S., and YY.Y collected the data and follow-up; SS.F and KH.L. performed the data analysis; YM.L., X.L., and YY.C. revised the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (Grant No. 2021JJ40297), Hunan Provincial People’s Hospital RENSHU Funding Project (Grant No. RS201801), Young Doctor Fund and Fund for Fostering of the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. BSJJ201806), and Hunan Provincial Health Commission project (Grant No. D202314016355, 202203052969).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1.Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- 2. Chung EYM, Palmer SC, Natale P, Krishnan A, Cooper TE, Saglimbene VM, et al. Incidence and outcomes of COVID-19 in people with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(6):804–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen CY, Shao SC, Chen YT, Hsu CK, Hsu HJ, Lee CC, et al. Incidence and clinical impacts of COVID-19 infection in patients with hemodialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis of 396,062 hemodialysis patients. Healthcare. 2021;9(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh J, Malik P, Patel N, Pothuru S, Israni A, Chakinala RC, et al. Kidney disease and COVID-19 disease severity-systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2022;22(1):125–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hilbrands LB, Duivenvoorden R, Vart P, Franssen CFM, Hemmelder MH, Jager KJ, et al. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(11):1973–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ozturk S, Turgutalp K, Arici M, Odabas AR, Altiparmak MR, Aydin Z, et al. Mortality analysis of COVID-19 infection in chronic kidney disease, haemodialysis and renal transplant patients compared with patients without kidney disease: a nationwide analysis from Turkey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(12):2083–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alfano G, Ferrari A, Magistroni R, Fontana F, Cappelli G, Basile C. The frail world of haemodialysis patients in the COVID-19 pandemic era: a systematic scoping review. J Nephrol. 2021;34(5):1387–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flythe JE, Assimon MM, Tugman MJ, Chang EH, Gupta S, Shah J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of individuals with pre-existing kidney disease and COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(2):190–203.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hsu CM, Weiner DE, Aweh G, Miskulin DC, Manley HJ, Stewart C, et al. COVID-19 among US dialysis patients: risk factors and outcomes from a national dialysis provider. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(5):748–56.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yavuz D, Karagöz Özen DS, Demirağ MD. COVID-19: mortality rates of patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2022;54(10):2713–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fisher M, Yunes M, Mokrzycki MH, Golestaneh L, Alahiri E, Coco M. Chronic hemodialysis patients hospitalized with COVID-19: short-term outcomes in the bronx, New York. Kidney360. 2020;1(8):755–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kular D, Chis Ster I, Sarnowski A, Lioudaki E, Braide-Azikiwe DCB, Ford ML, et al. The characteristics, dynamics, and the risk of death in COVID-19 positive dialysis patients in London, UK. Kidney360. 2020;1(11):1226–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang F, Ao G, Wang Y, Liu F, Bao M, Gao M, et al. Risk factors for mortality in hemodialysis patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2021;43(1):1394–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bao WJ, Fu SK, Zhang H, Zhao JL, Jin HM, Yang XH. Clinical characteristics and short-term mortality of 102 hospitalized hemodialysis patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.2.2.1 variant in Shanghai, China. New Microbes New Infect. 2022;49:101058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pan Y, Wang L, Feng Z, Xu H, Li F, Shen Y, et al. Characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Beijing during 2022: an epidemiological and phylogenetic analysis. Lancet. 2023;401(10377):664–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, Cao Y, Alwalid O, Gu J, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang X, Chen Q, Xu G. Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 infection in dialysis patients and protective effect of COVID-19 vaccine. Inflamm Res. 2023;72(5):989–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghonimi TAL, Alkad MM, Abuhelaiqa EA, Othman MM, Elgaali MA, Ibrahim RAM, et al. Mortality and associated risk factors of COVID-19 infection in dialysis patients in Qatar: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Du X, Li H, Dong L, Li X, Tian M, Dong J. Clinical features of hemodialysis patients with COVID-19: a single-center retrospective study on 32 patients. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(9):829–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang W, Yang S, Wang L, Zhou Y, Xin Y, Li H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 310 SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant patients and comparison with Delta and Beta variant patients in China. Virol Sin. 2022;37(5):704–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zeng QL, Lv YJ, Liu XJ, Jiang ZY, Huang S, Li WZ, et al. Clinical characteristics of omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant infection after non-mRNA-based vaccination in China. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:901826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu J, Li J, Zhu G, Zhang Y, Bi Z, Yu Y, et al. Clinical features of maintenance hemodialysis patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(8):1139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. George PM, Barratt SL, Condliffe R, Desai SR, Devaraj A, Forrest I, et al. Respiratory follow-up of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Thorax. 2020;75(11):1009–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alberici F, Delbarba E, Manenti C, Econimo L, Valerio F, Pola A, et al. A report from the Brescia Renal COVID Task Force on the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of hemodialysis patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):20–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corbett RW, Blakey S, Nitsch D, Loucaidou M, McLean A, Duncan N, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in an urban dialysis center. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(8):1815–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goicoechea M, Sánchez Cámara LA, Macías N, Muñoz de Morales A, Rojas ÁG, Bascuñana A, et al. COVID-19: clinical course and outcomes of 36 hemodialysis patients in Spain. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tortonese S, Scriabine I, Anjou L, Loens C, Michon A, Benabdelhak M, et al. COVID-19 in patients on maintenance dialysis in the Paris region. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(9):1535–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valeri AM, Robbins-Juarez SY, Stevens JS, Ahn W, Rao MK, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Presentation and outcomes of patients with ESKD and COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(7):1409–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jager KJ, Kramer A, Chesnaye NC, Couchoud C, Sánchez-Álvarez JE, Garneata L, et al. Results from the ERA-EDTA Registry indicate a high mortality due to COVID-19 in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients across Europe. Kidney Int. 2020;98(6):1540–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hartantri Y, Debora J, Widyatmoko L, Giwangkancana G, Suryadinata H, Susandi E, et al. Clinical and treatment factors associated with the mortality of COVID-19 patients admitted to a referral hospital in Indonesia. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023;11:100167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324(8):782–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vidal-Cevallos P, Higuera-De-La-Tijera F, Chávez-Tapia NC, Sanchez-Giron F, Cerda-Reyes E, Rosales-Salyano VH, et al. Lactate-dehydrogenase associated with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Mexico: a multi-centre retrospective cohort study. Ann Hepatol. 2021 Sep-Oct;24:100338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gupta GS. The lactate and the lactate dehydrogenase in inflammatory diseases and major risk factors in COVID-19 patients. Inflammation. 2022;45(6):2091–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun Z, Zhang N, Li Y, Xu X. A systematic review of chest imaging findings in COVID-19. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2020;10(5):1058–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tian M, Li H, Yan T, Dai Y, Dong L, Wei H, et al. Clinical features of patients undergoing hemodialysis with COVID-19. Semin Dial. 2021;34(1):57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.