Abstract

A patient in his 60s presented with severe keratitis in his right eye. He had a background of diabetes, high body mass index, arthritis and limited mobility, and high alcohol intake. Examination showed lower lid tarsal ectropion, floppy eyelid syndrome, advanced meibomian gland dysfunction, moderate neurotrophia, and large inferior keratitis with hypopyon. Corneal scrapes revealed Enterococcus faecalis, sensitive to vancomycin and ciprofloxacin only. Due to poor compliance with vancomycin, he was started on topical ciprofloxacin resulting in partial improvement but a persistent epithelial defect. Inserting a dry patch of amniotic membrane on the cornea accelerated epithelialization, and 11 weeks from presentation, complete corneal healing was noted.

In the presence of multiple systemic and ocular risk factors like diabetes, high body mass index, high alcohol intake, tarsal ectropion, floppy eyelid syndrome, neurotrophic cornea, blepharitis, and ocular surface inflammation, atypical keratitis, like this rare infection, should be suspected. The use of dry amniotic membrane has a role in epithelial healing in patients with neurotrophia.

Keywords: microbial keratitis, amniotic membrane, keratitis, enterococcus faecalis (e. faecalis), cornea

Introduction

Enterococci, gram-positive facultative anaerobes mainly found in the alimentary tract, typically cause various infections but are seldom associated with ocular issues [1]. While Enterococcus-induced ocular infections are rare, they have been reported in conditions such as post-cataract extraction endophthalmitis [2-4], conjunctivitis, and orbital cellulitis [5]. Enterococcus faecalis keratitis is an exceptionally uncommon infection, with previously reported cases shown in the Appendices [1,6-11]. Predominantly affecting females, Enterococcus-related keratitis is often linked to ocular surface diseases, corneal graft history, contact lens wearing, and steroid use [11]. This infection poses a clinical challenge due to its potential virulence, including reported cases of perforation at presentation, and the multi-antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus [11]. Although vancomycin is often effective, its unavailability for keratitis management, resistance, and potential epithelial toxicity present additional hurdles [6,9,11,12]. This study aims to contribute by reporting a case of Enterococcus faecalis keratitis in the background of moderate neurotrophia, shedding light on the associated clinical challenges.

Case presentation

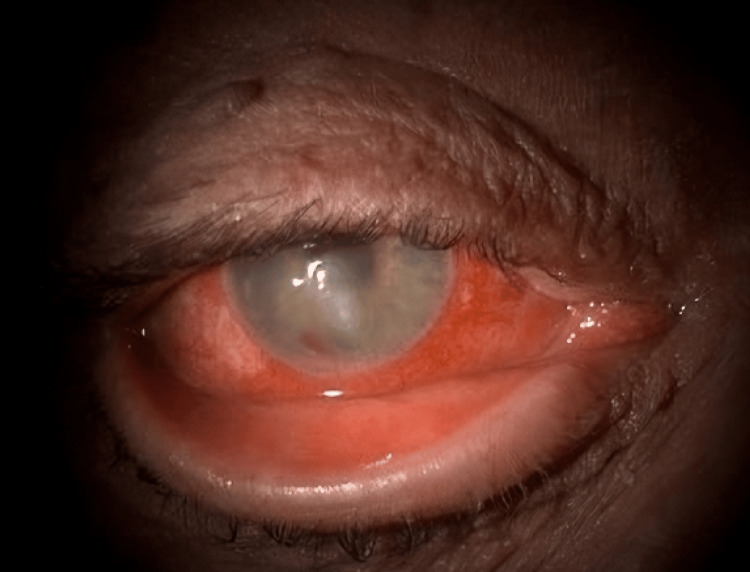

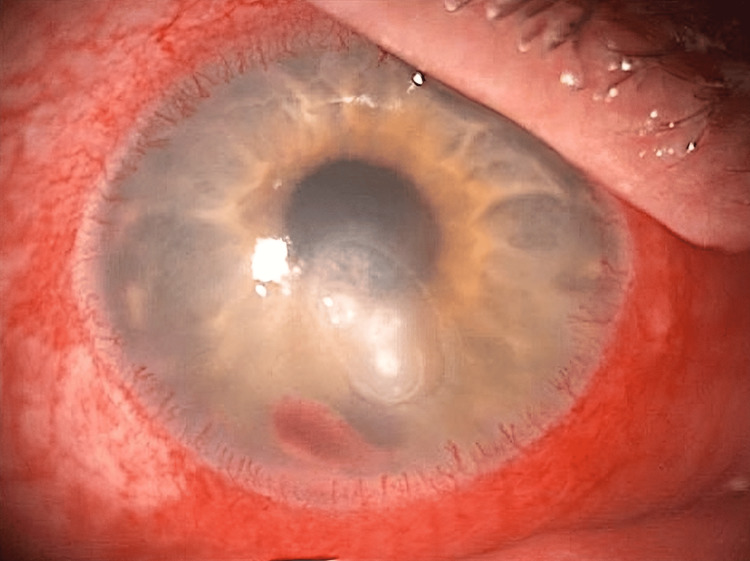

A man in his early 60s presented with painful redness and reduced vision in his right eye for two days. His left eye, densely amblyopic, relied on his right eye with a historic uncorrected visual acuity of 0.1 logMAR. He had a medical history of type II diabetes, high body mass index (BMI), and arthritis and a social history of a recent reduction in alcohol intake from 11 units to 4 units daily while living with his wife and dog. At presentation, his vision was 0.95 logMAR in the right eye and 1.1 logMAR in the left. Examination revealed a right lower lid tarsal ectropion, injected conjunctival vessels, large inferior keratitis (4.3 mm × 3.1 mm), and a 1.2 mm hypopyon (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Corneal sensation was partially reduced in both eyes, and the posterior segment view was limited, with no vitritis detected on the ultrasound scan. The ulcer did not look like a geographical ulcer, there was no localised neovascularisation, and he had no previous history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis.

Figure 1. Right eye tarsal ectropion and corneal ulcer associated with hypopyon.

Figure 2. Inferior keratitis, hypopyon, and peripheral neovascularisation.

Initial corneal scrapes were inconclusive, showing no organism growth on various agar types. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Acanthamoeba was negative. Treatment with levofloxacin yielded no improvement. A subsequent corneal scrape grew Enterococcus faecalis, sensitive to vancomycin, amoxicillin, and teicoplanin.

The patient initially received off-license topical vancomycin 5% eye drops hourly for 48 hours, causing discomfort and poor compliance due to burning sensations. Amoxicillin and teicoplanin were not available in the form of eye drops; therefore, sensitivity testing was repeated with available topical antibiotics, revealing sensitivity to ciprofloxacin. Hence, a switch to Ciloxan® 0.3% eye drops was prompted. This eye drop was applied every hour for 48 hours, followed by a daytime hourly application for another two days, and then reduced to a two-hour daytime application for another 10 days. Two weeks from commencing the intensive topical antibiotic, there was a partial improvement; however, the epithelial defect remained the same. Meibomian gland dysfunction, ocular surface inflammation, and moderate neurotrophic factors delayed healing. A tapering dose of preservative-free dexamethasone 0.1% was added thrice daily followed by twice and then once daily over three weeks, addressing discomfort and inflammation. During this time, the patient continued with ciprofloxacin eye drops six times a day.

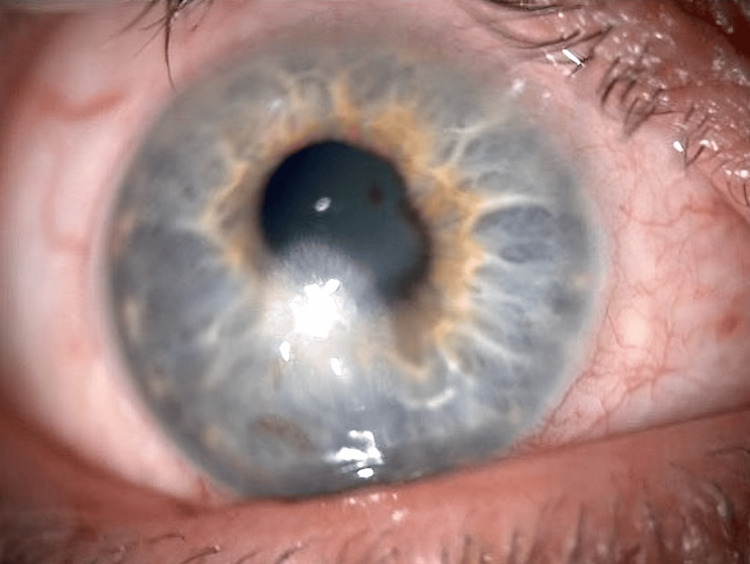

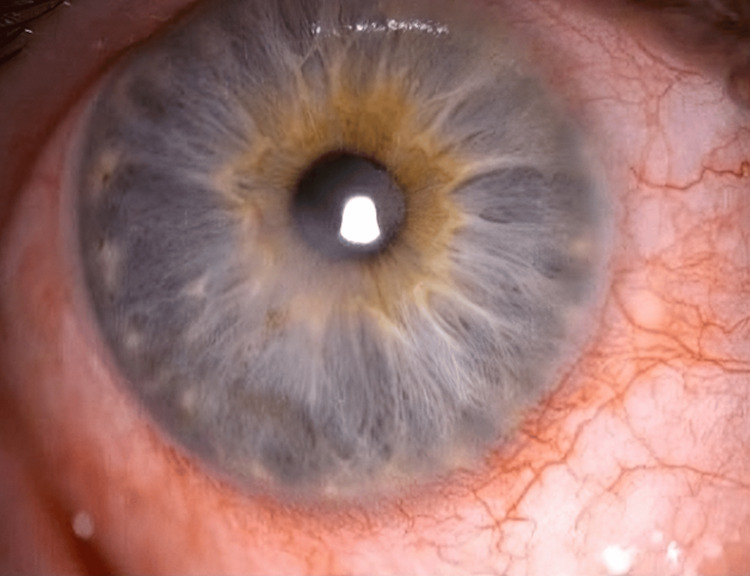

Five weeks from the beginning of the treatment, the epithelial defect measured 3.1 mm × 2.2 mm (Figure 3). At this point, amniotic membrane application initiated healing, reducing the defect to 1.5 mm × 0.7 mm after one week. The dry amniotic membrane disc was secured with a bandage contact lens, and to allow reasonable vision, it had a hole in the centre, which spared the visual axis. After the removal of the bandage contact lens, treatment continued with ciprofloxacin six times daily, preservative-free lubricating eye drops, nighttime lubricating ointment, lid hygiene, and once-daily preservative-free hydrocortisone sodium phosphate eye drop (Softacort®) for a month. Complete epithelialization, improved ocular surface (Figure 4), and unaided visual acuity of 0.1 logMAR were achieved 11 weeks post-presentation.

Figure 3. Persistent epithelial defect despite topical antibiotics and addressing the ocular surface inflammation.

Figure 4. Resolved keratitis and fully healed epithelial defect 11 weeks from the presentation.

Discussion

Enterococcus faecalis keratitis is an exceedingly rare occurrence, documented in only a number of cases prior to this report [1,6-11]. The typical source of this infection involves post-operative complications, often following keratoplasties [7,8] or as a result of ocular surgery-associated factors [1]. However, in this instance, the patient had no history of ocular surgery or contact lens use. Instead, his compromised ocular surface, secondary to meibomian gland dysfunction, tarsal ectropion, floppy eyelid syndrome, and neurotrophic cornea, possibly linked to diabetes and high alcohol intake, created an environment conducive to this rare infection and a non-healing epithelial defect. Given the initial corneal scrap was inconclusive, it could be assumed that this case was a viral keratitis with a secondary Enterococcus faecalis infection. However, primary bacterial infection remained suspected for a number of reasons including no previous history of HSV keratitis, round and well-demarcated edges of persistent epithelial defects (PED), rather than the geographical pattern in viral keratitis, absence of localised neovascularisation despite the chronicity of the PED, and equal neurotrophia in both cornea. Therefore, this was presumed to be a case of primary Enterococcus faecalis keratitis. Notably, the patient's interaction with a dog could have introduced Enterococcus faecalis, as multidrug-resistant strains have been identified in the intestinal tracts of animals [9].

Enterococcus faecalis poses a significant threat to the cornea, triggering an intense and rapidly progressing inflammatory response [7], often leading to necrosis and corneal melting [9], proving effective prompt treatment to be essential. Treating Enterococcus faecalis however presents considerable challenges. In vitro antibiotic sensitivity testing may not align with the clinical in vivo response to antimicrobials [6]. Although vancomycin is a common choice for sensitivity, its usage is limited by factors such as ocular toxicity and poor patient compliance [6,8,9,11]. Additionally, the scarcity of topical vancomycin in the UK, compounded by its off-label use, introduces delays in treatment initiation. The rise of intrinsic and acquired resistance to multiple antibiotics, including vancomycin, further complicates the therapeutic landscape.

Alternative treatments have shown promise in vancomycin-resistant cases. Various topical antibiotic regimens have been explored, with combinations like fortified vancomycin and ciprofloxacin proving effective [11]. In cases refractory to monotherapy, combinations like fortified tobramycin and cefazolin [11] or vancomycin and gentamicin [7] have been successful.

In this reported case, despite topical treatment, an epithelial defect persisted. The management involved the application of a dry amniotic membrane, leveraging its regenerative properties. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of dry amniotic membrane use in an Enterococcus faecalis infection and neurotrophic cornea. Amniotic membrane, whether dehydrated or not, has proven effective in treating PED and non-healing corneal ulcers [13]. This has been shown to have a 70% success rate in corneal ulcers and established as useful in a variety of aetiologies such as herpetic ulcers, rheumatic disease, penetrating keratoplasty, and trauma [14]. Examples of infection-related epithelial defects treated with amniotic membrane include Pseudomonas, Acanthamoeba, and Aspergillus keratitis [15]. In this instance, the patient experienced improvement despite retaining the membrane for only six days, highlighting the potential benefit of amniotic membrane use for PED in Enterococcus faecalis infection, even in limited application.

While the patient continued to recover, further corrective measures, including surgical intervention for ectropion correction, were considered. Two years following the management of keratitis and optimising his ocular surface, there has been no recurrence of keratitis. This multifaceted case emphasizes the intricate challenges in diagnosing and treating Enterococcus faecalis keratitis, showcasing the need for tailored approaches and continued exploration of alternative treatments such as amniotic membrane application.

Conclusions

Enterococcus faecalis keratitis may be suspected when multiple ocular and systemic risk factors are present. This rare infection presents a clinical challenge due to its high virulence, multi-antibiotic resistance, and poor antibiotic compliance. Managing such complex cases requires a staged approach, focusing on treating the infection and addressing all comorbidities to achieve success. This case also highlights the benefit of using a dry amniotic membrane to aid in the healing of PED in Enterococcus faecalis keratitis with moderate neurotrophia.

Appendices

Table 1. Summary of the reported cases with Enterococcus faecalis keratitis.

LP: light perception; IOL: intra-ocular lens; NA: not applicable; CF: counting fingers; PKP: penetrating keratoplasty; BCL: bandage contact lens; DMEK: Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty; DSEK: Descemet's stripping endothelial keratoplasty; SCL: scleral contact lens; AF: atrial fibrillation; CCF: congestive cardiac failure; CVA: cerebrovascular attack; AIDS: acquired immune deficiency syndromes

| Case | Age (y) | Sex | Presenting visual acuity | Social history | Past medical history | Contact lens wearer | Past ocular history | Topical drops | Outcome | Culture results | Polymicrobial |

| Lee and Lee, 2004 [1] | 67 | F | LP | NA | Diabetes mellitus | No | Phaco/IOL, endophthalmitis | None | Intravitreal vancomycin, amikacin, and amphotericin; second intravitreal injection on vancomycin, ceftazidime, and dexamethasone; third intravitreal injection of vancomycin and dexamethasone; topical vancomycin and fortified amikacin. Vitreous opacity resolved but corneal opacity and neovascularisation remained | E. faecalis | No |

| Subashini et al., 2007 [6] | 30 | F | CF | NA | NA | No | Injury to the eye with fingernail | Ofloxacin | Resolved with a remaining corneal scar with topical vancomycin | E. faecalis | No |

| Sherman et al., 1992 [7] | 61 | M | 20/400 | NA | NA | BCL | PKP, herpetic keratouveitis | None | Resolved on vancomycin and gentamicin | E. faecalis | No |

| Sudana et al., 2021 [8] | 64 | M | 20/600 | NA | NA | No | DMEK, pseudophakia | Presumed topical steroids (post-op graft patient but steroids not specifically mentioned in report) | Topical vancomycin, removal of DMEK, new DSEK | E. faecalis | No |

| Peng et al., 2009 [9] | 23 | F | 20/50 | Works as a pet groomer | NA | No | No | None | Cefazolin sodium, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, vancomycin, epithelial debridement | E. faecalis | No |

| Lam et al., 1993 [10] | 65 | F | NA | NA | NA | BCL | PKP, endophthalmitis, alkali burns, cataract extraction, cyclocryotherapy for glaucoma | None | Fortified vancomycin, PKP | E. faecalis | No |

| Lam et al., 1993 [10] | 88 | F | CF | NA | NA | No | PKP, amblyopia | None | Fortified vancomycin, PKP, extracapsular cataract extraction, IOL implantation | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 17 | F | 20/200 | NA | None | Yes, SCL | None | None | Resolved on moxifloxacin | B. cereus, E. faecalis, K. pneumoniae | Yes |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 21 | F | 20/40 | NA | None | Yes, SCL | None | None | Resolved on moxifloxacin | P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, E. faecalis | Yes |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 85 | M | HM | NA | Anemia, hypothyroidism, hypertension | No | Lamellar keratoplasty, two PKP, Mooren ulcer | Cyclosporine (2/2), artificial tears, tobramycin/ dexamethasone | PKP #3 | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 58 | F | 20/25 | NA | None | Yes, SCL | Epithelial basement membrane dystrophy | Artificial tears | Resolved on moxifloxacin | E. faecalis Coagulase-negative S. aureus | Yes |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 55 | F | NA | NA | NA | Yes, SCL | None | NA | PKP | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 73 | M | NA | NA | Bladder cancer | No | PKP | NA | NA | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 57 | F | NA | NA | None | Yes, SCL | None | None | Resolved on fortified vancomycin | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 89 | F | NA | NA | None | No | AMD | None | Resolved on fortified vancomycin | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 23 | F | 20/60 | NA | None | Yes, SCL | None | None | Resolved on fortified vancomycin, ciprofloxacin | P. aeruginosa, E. faecalis, S. marcescens | Yes |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 85 | F | 5/200 | NA | Hypercholesterolemia | Yes, SCL | Cataract extraction | Timoptic 0.5% | Resolved on ofloxacin | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 41 | F | CF | NA | None | No | Entropion | None | Resolved on moxifloxacin | E. faecalis, S. aureus | Yes |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 49 | M | 20/30 | NA | AIDS | No | Foreign body removal | None | Resolved on ofloxacin | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 98 | F | CF | NA | AF, CCF, CVA, ovarian cancer, anemia, pacemaker | No | Entropion | None | PKP | E. faecalis | No |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 74 | F | 20/300 | NA | Schizophrenia, depression, paranoia, osteoporosis, hypothyroidism | No | Grave's ophthalmopathy, lagophthalmos | Pred Forte, Polytrim, Polysporin | Resolved on ciprofloxacin | E. faecalis, S. sciuri Corynebacterium species | Yes |

| Rau et al., 2008 [11] | 37 | F | CF | NA | Migraine, appendectomy | Yes, SCL | Keratoconus | None | Resolved on fortified tobramycin and cefazolin | E. faecalis | No |

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Mohammad Saleki, Zahra Ashena, Magdalena Niestrata

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Mohammad Saleki, Zahra Ashena, Magdalena Niestrata

Drafting of the manuscript: Mohammad Saleki, Zahra Ashena, Magdalena Niestrata

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mohammad Saleki, Zahra Ashena, Magdalena Niestrata

Supervision: Zahra Ashena

References

- 1.A case of Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis with corneal ulcer. Lee SM, Lee JH. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2004;18:175–179. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2004.18.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recurrent Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis after phacoemulsification. Teoh SC, Lee JJ, Chee CK, Au Eong KG. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2004.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus faecalis: antibiotic selection and treatment outcomes. Scott IU, Loo RH, Flynn HW Jr, Miller D. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1573–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Recurrent enterococcal endophthalmitis following cataract surgery: a case report. Nasrallah FP, Desai SA. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10392737/ Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999;30:481–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ethmoiditis, conjunctivitis, and orbital cellulitis due to enterococcus infection. Elitsur Y, Biedner BZ, Bar-Ziv J. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6420105/ Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1984;23:123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stromal abscess caused by Enterococcus fecalis: an unusual presentation. Subashini K, Arvind G, Sabyasachi S, Renuka S. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:160–161. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.30723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enterococcus faecalis infection in a corneal graft. Sherman MD, Ostler HB, Biswell R, Cevallos V. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:233–234. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delayed postoperative interface keratitis due to Enterococcus faecalis after Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty. Sudana P, Chaurasia S, Joseph J, Mishra DK. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:0. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-238389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Multiresistant enterococci: a rare cause of complicated corneal ulcer and review of the literature. Peng CH, Cheng CK, Chang CK, Chen YL. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44:214–215. doi: 10.3129/i09-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enterococcal infectious crystalline keratopathy. Lam S, Meisler DM, Krachmer JH. Cornea. 1993;12:273–276. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199305000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Incidence and clinical characteristics of enterococcus keratitis. Rau G, Seedor JA, Shah MK, Ritterband DC, Koplin RS. Cornea. 2008;27:895–899. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31816f633b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clonal diversity of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from an outbreak in a tertiary care university hospital. Pearce CL, Evans MK, Peters SM, Cole MF. Am J Infect Control. 1998;26:563–568. doi: 10.1053/ic.1998.v26.a91614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amniotic membrane in ophthalmology: properties, preparation, storage and indications for grafting-a review. Jirsova K, Jones GL. Cell Tissue Bank. 2017;18:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s10561-017-9618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Efficacy of amniotic membrane transplantation for the treatment of corneal ulcers. Schuerch K, Baeriswyl A, Frueh BE, Tappeiner C. Cornea. 2020;39:479–483. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amniotic membrane transplantation in infectious corneal ulcer. Kim JS, Kim JC, Hahn TW, Park WC. Cornea. 2001;20:720–726. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]