Abstract

Cytomegalovirus latency depends on an interaction with hematopoietic cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood. The distribution of viral DNA was investigated by PCR-driven in situ hybridization (PCR-ISH), and the number of viral genomes per cell was estimated by quantitative competitive PCR during both experimental and natural latent infection. During experimental latent infection of cultured granulocyte-macrophage progenitors, the viral genome was detected in >90% of cells at a copy number of 1 to 8 viral genomes per cell. During natural infection, viral genomes were detected in 0.004 to 0.01% of mononuclear cells from granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-mobilized peripheral blood or bone marrow from seropositive donors, at a copy number of 2 to 13 genomes per infected cell. When evaluated by reverse transcription–PCR-ISH, only a small proportion of experimentally infected cells (approximately 2%) had detectable latent transcripts. This investigation identifies the small percentage of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells that become latently infected during natural infection and suggests that latency may proceed in some cells that fail to encode currently identified latent transcripts.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a medically important betaherpesvirus carried by a majority of individuals, where it is a leading cause of opportunistic and congenital disease (4). Like other herpesviruses, primary infection by CMV leads to a lifelong latency that is characterized by maintenance of the viral genome without active infectious virus production. Periodically throughout life, the virus reactivates from latency and is shed in bodily secretions including saliva, urine, and breast milk. Although primary and reactivated infection remain largely asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, primary infection by CMV is a significant cause of serious congenital disease leading to neurological damage in children. Reactivated infection is a major cause of disease in immunocompromised individuals including AIDS patients and allograft transplant recipients (4). The ability of this virus to reactivate from a latent state contributes significantly to its success as a human pathogen, yet the tissue distribution of latent CMV remains poorly understood (24).

Peripheral blood (PB)- and bone marrow (BM)-derived monocytes and granulocyte-macrophage progenitor cells (GM-Ps) may be important sites of CMV latency. The viral genome is maintained in cultured primary GM-Ps during experimental latent infection (9, 11–13) and is detected in naturally infected PB- and BM-derived mononuclear cells from healthy seropositive donors (2, 11, 13, 21, 26, 33–35). In addition, reactivation of virus has been induced in experimentally infected GM-Ps by cocultivation with permissive cells or by treatment with proinflammatory cytokines (9, 11) as well as in naturally infected PB mononuclear cells (PBMCs) following allogeneic stimulation (30). Previous studies have identified CMV latency-associated transcripts (CLTs) in experimentally and naturally infected hematopoietic progenitor cells (9, 11–13). Two classes of CLTs (denoted sense and antisense) have been mapped to the ie1/ie2 (UL122/UL123) region of the viral genome, a region that encodes the major α (immediate-early) gene products. Antibodies to latent proteins encoded by these CLTs have been detected in serum from healthy seropositive donors (13).

To date, quantitation of latent infection during natural infection has proved complicated due primarily to the need to apply PCR methods to detect latent viral DNA and CLTs. Methods that rely on in situ hybridization (ISH) to enumerate RNA- or DNA-positive cells, particularly when combined with PCR amplification to increase the sensitivity for low copy numbers, provide the most accurate picture of the distribution of latent virus nucleic acids in host cells and tissues (8). In this study, we sought to characterize CMV latency by applying PCR-driven ISH (PCR-ISH) and quantitative competitive PCR (QC-PCR) to experimentally infected GM-Ps and naturally infected mononuclear cells to estimate the percentage of these cells that harbor viral genomes as well as the average number of genomes carried by a latently infected cell. We also used reverse transcription-PCR-ISH (RT-PCR-ISH) to determine the percentage of CMV genome-positive cells with detectable sense CLTs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus culture.

Human fetal liver hematopoietic cells were cultured as GM-Ps as described previously (11). On day 4 of cell culture, nonadherent cells were infected with RC256, a lacZ-tagged derivative of human CMV Towne (32), at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 3. Nonadherent cells were maintained by collection and transfer to new flasks three times per week to remove stromal cells and differentiated, adherent myelomonocytic cells. Human foreskin fibroblasts were used for virus propagation and plaque assay.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized PB or BM cells were collected from patients at Stanford Medical Center, layered over 15 ml of Lymphoprep (GIBCO/BRL), and centrifuged for 15 min at 1,000 × g. Cells were washed once in HEPES-buffered saline solution, treated with 155 mM NH4Cl–10 mM KHCO3 (pH 7.0) for 5 min to lyse any remaining erythrocytes, and washed twice with HEPES-buffered saline solution before either PCR-ISH or QC-PCR.

PCR-ISH and DNA blot hybridization.

PCR-ISH was performed by a modification of the method described by Haase et al. (8). Cells were harvested and fixed with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, washed three times in PBS, and suspended in a PCR mixture consisting of 200 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 0.01% gelatin, oligonucleotide primers at 1 pmol/μl each, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1× PCR buffer (Boehringer Mannheim). PCR amplification was carried out with the ie1/ie2 primers IEP3A and IEP3B (11) in a Perkin-Elmer/Cetus thermocycler for 30 cycles (94°C for 2 min, 58°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 5 min) after an initial denaturation at 94°C for 8 min. Following PCR amplification, the cells were washed and suspended in PBS and collected onto glutaraldehyde-activated 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane-coated glass microscope slides by cytocentrifugation (19). The cells were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 30 min, washed twice in PBS, and then treated with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min. They were washed three times in PBS, treated with 0.25% acetic anhydride–0.1 M triethanolamine (pH 8.0) for 10 min, washed three times in PBS, and dehydrated through graded (50, 70, and 100%) ethanol. In situ detection of amplified products was performed with a nonisotopic digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled riboprobe generated from a genomic clone, pON2810, which consists of a 2.2-kb AlwNI restriction fragment from the ie1/ie2 region of human CMV AD169 cloned into the SmaI site of pBluescript KS (+/−). A 20-μl volume of hybridization solution (50% deionized formamide, 1× SSC [0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M sodium citrate], 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 10 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 0.02% Ficoll, 0.02% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 500 μg of sheared denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml, 500 μg of yeast tRNA per ml, 20 mM dithiothreitol, 1 U of RNase inhibitor per μl, 30 pg of probe) was added to each cell spot, and the slides were each covered with a siliconized coverslip and sealed with rubber cement. The slides were then placed onto a heating block for 8 min at 98°C to denature target DNA, cooled rapidly on ice for 2 min, and incubated for 16 h at 58°C. Unbound probe was removed by washing the slides sequentially in 2× SSC–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 30 min at room temperature, 0.1× SSC–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 30 min at room temperature, and 0.1× SSC–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–30% deionized formamide for 30 min at 58°C. Finally, the slides were washed at room temperature in 0.1× SSC–10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 15 min. Bound probe was detected with anti-DIG antibody coupled to alkaline phosphatase and developed with nitroblue tetrazolium chloride plus 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate as specified by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). In DNA blot experiments, DNA was transferred from 3% agarose gels to nitrocellulose membranes by the method of Southern (31) and hybridized to a random-primed 32P-labelled probe generated from pON2810. Hybridization, washing of filters, and detection of bound probe were carried out as previously described (28), with the addition of 15% deionized formamide to the hybridization solution.

QC-PCR.

Cells were suspended in lysis buffer at either 1.3 × 104 or 5.4 × 104 cells per 10 μl and incubated as described previously (11). Each 10-μl aliquot of cell lysate was analyzed in the presence of between 3 and 3 × 105 copies of a denatured CMV ie1/ie2 cDNA competitor pON2347 (11). PCR amplification for either 30 or 40 cycles (94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min) was performed with primers IEP3C and IEP4BII (11). After amplification, 20% of each reaction mixture was analyzed by electrophoresis in 3% agarose gels. In some experiments, PCR products were also analyzed by DNA blot hybridization as described above. The relative quantities of PCR products derived from genomic and competitor templates were determined by density integration with a Stratagene Eagle Eye II/Eagle Sight system or Molecular Dynamics Storm 860 PhosphorImager. The ability of primers IEP3C and IPE4BII to amplify equally both viral genomic and competitor sequences was confirmed by performing a PCR on a sample containing a mixture of 105 copies of virion DNA and 105 copies of pON2347 under the reaction conditions described above. PCR products resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and density integration demonstrated that both templates were amplified equally (data not shown).

RT-PCR-ISH.

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, washed three times in PBS, and resuspended in DNase digestion mixture (6 mM MgCl2, 40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 U of DNase per μl, 0.15 U of RNase inhibitor per μl, 1 mM dithiothreitol) (GIBCO/BRL) for 16 h at 37°C. The cells were washed three times in PBS and suspended in RT mixture (0.15 U of RNase inhibitor per μl, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 1× RT buffer, 1.25 pmol of primer IEP2D per μl, 10 U of SuperScript II per μl) (GIBCO/BRL) for 4 h at 42°C. They were then washed three times in PBS and finally suspended in PCR mixture containing primers IEP2D and IEP1G (12). PCR amplification was done as described previously, and amplified products were detected by ISH with a DIG-labelled riboprobe derived from pON2501, which contains a 1.1-kb EcoRV-SpeI cDNA fragment from the ie1/ie2 region of CMV AD169 cloned into the ClaI-SpeI site of pBluescript KS (+/−).

RESULTS

Quantitation of viral DNA in CMV-infected GM-P cultures.

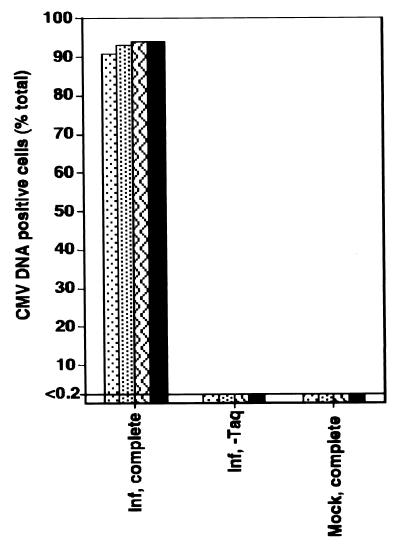

Viral DNA and limited transcription from the viral genome have been detected in experimentally infected GM-Ps maintained in culture in the absence of any detectable productive infection, in a pattern consistent with viral latency (9, 11–13). To better understand the distribution of viral DNA in these cells, we used PCR-ISH to investigate the percentage of cells harboring viral genomes. Human fetal liver-derived GM-Ps grown in suspension under conditions previously described (11) were exposed to a lacZ-tagged human CMV RC256 at a MOI of 3. At 2 to 3 weeks after infection, the nonadherent cell population from four separate suspension cultures was collected, evaluated for evidence of productive infection, and subjected to PCR-ISH to reveal the distribution of viral DNA. Cells from each culture were assayed for β-galactosidase expression as a sensitive indicator of viral productive-phase gene expression (32). Cultures evaluated for β-galactosidase or directly for infectious virus exhibited no evidence of productive infection (data not shown), consistent with previous results (11). Mononuclear cells were fixed as described in Materials and Methods, subjected to 30 cycles of PCR amplification with CMV primers IEP3A and IEP3B, collected on glass slides by cytocentrifugation, and subjected to nonisotopic ISH with a DIG-labelled riboprobe homologous to the amplified product (Fig. 1A to D). Viral DNA was detected in >90% of cells in all infected samples in the presence of Taq DNA polymerase and primers (Fig. 2) but not in mock-infected samples or in virus-infected samples in which either Taq DNA polymerase or primers were omitted (Fig. 2 and data not shown). These results demonstrated that over 90% of cells harbored viral DNA in the absence of any concurrent productive infection, consistent with previous evidence suggesting that such cultures were latently infected (9, 11–13).

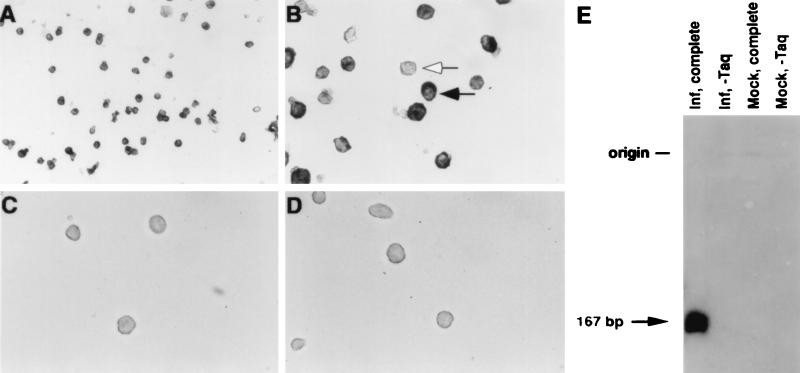

FIG. 1.

(A to D) Photomicrographs showing detection of CMV DNA in experimentally infected GM-P culture by PCR-ISH. Cells from RC256-infected (A to C) or mock-infected (D) cultures were subjected to PCR-ISH, except that Taq DNA polymerase was omitted from the experiment in panel C. The solid arrow indicates a CMV DNA-positive cell, and the open arrow indicates a CMV DNA-negative cell. Magnification, ×1,280 (A) and ×3,200 (B to D). (E) DNA blot hybridization of total DNA extracted from CMV-infected (Inf, complete) or mock-infected (Mock, complete) GM-Ps after PCR amplification with IEP3A and IEP3B or with the omission of Taq DNA polymerase (Inf, −Taq and Mock, −Taq). The filter was probed with a 32P-labelled probe derived from pON2810, washed, and exposed to X-ray film for 2 h. The predicted CMV-specific PCR product of 167 bp is indicated.

FIG. 2.

PCR-ISH determination of the percentage of CMV

DNA-positive cells from four separate GM-P cultures 2 to 3 weeks after

infection with RC256 at a MOI of 3. Virus-infected (Inf) and

mock-infected (Mock) cultures were analyzed in the presence of the full

complement of reagents for CMV DNA detection (complete) or with the

omission of Taq DNA polymerase (−Taq). Symbols: ⊡, experiment 1;

, experiment 2;  ,

experiment 3; ■, experiment 4.

,

experiment 3; ■, experiment 4.

Several reports (8, 10, 17) have suggested that diffusion of products and nonspecific amplification may lead to false-positive results in PCR-ISH. To determine whether PCR products diffused between cells under the conditions used here, we mixed mock-infected cells with infected GM-Ps at a ratio of 10:1 prior to performing PCR-ISH. This resulted in a concomitant reduction in the numbers of CMV DNA-positive cells and indicated that diffusion of PCR products did not contribute signal in our analysis. The specificity of the PCR products made during PCR-ISH was also investigated. DNA extracted after the PCR amplification was separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and subjected to DNA blot hybridization with a random-primed 32P-labelled probe generated from the same construct (pON2810) used to generate the ISH probe (Fig. 1E). The samples prepared from infected GM-Ps contained an appropriately sized amplified species which was absent from either mock-infected samples or virus-infected samples in which Taq DNA polymerase was omitted from the PCR mixture. These data demonstrated that the PCR amplification and subsequent ISH were detecting a specific 167-bp region of the CMV genome in fixed mononuclear cells.

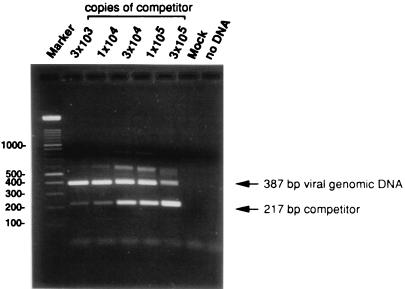

We used QC-PCR to determine the number of viral genome copies per infected GM-P in a culture where 94% of cells were CMV DNA positive by PCR-ISH. Cell lysates of 1.3 × 104 GM-Ps were mixed with 3 × 103 to 3 × 105 copies of a competitive template, the ie1/ie2 cDNA plasmid clone pON2347, and subjected to 30 rounds of PCR amplification with primers IEP3C and IEP4BII as previously described (11). Cells (1.3 × 104) from a mock-infected GM-P culture and a sample lacking cell or competitor DNAs were included as controls. After amplification, 20% of each reaction mixture was separated on a 3% agarose gel and products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Both the 387-bp genomic and 217-bp competitor PCR products were readily detectable (Fig. 3). Based on the relative amounts of the genomic and competitor PCR products, between 3 × 104 and 1 × 105 CMV genomes were present in 1.3 × 104 cells, representing two to eight genomes per cell. In two other infected GM-P cultures, a more precise estimation of one and four viral genomes per CMV DNA-positive cell was made. Taken together with previous results showing that viral DNA was contained in the nucleus of infected GM-Ps (11), the viral genome appears to be carried at a relatively low copy number during the establishment and maintenance of latency.

FIG. 3.

CMV DNA copy number determination by QC-PCR. Lysates of 1.3 × 104 cells from an RC256-infected GM-P culture (MOI of 3, day 17 postinfection) were each analyzed in the presence of 3 × 103 to 3 × 105 copies of competitive template, a CMV ie1/ie2 cDNA plasmid pON2347. The copy numbers are indicated above the lanes. The positions of the 387-bp product from CMV genomic DNA and the 217-bp product from the cDNA competitive template are indicated by arrows. Cells from a mock-infected GM-P culture (Mock) or a sample without DNA (no DNA) were included as negative controls. The marker was a 100-bp ladder (Boehringer-Mannheim).

Enumeration of experimentally infected cells expressing sense CLTs.

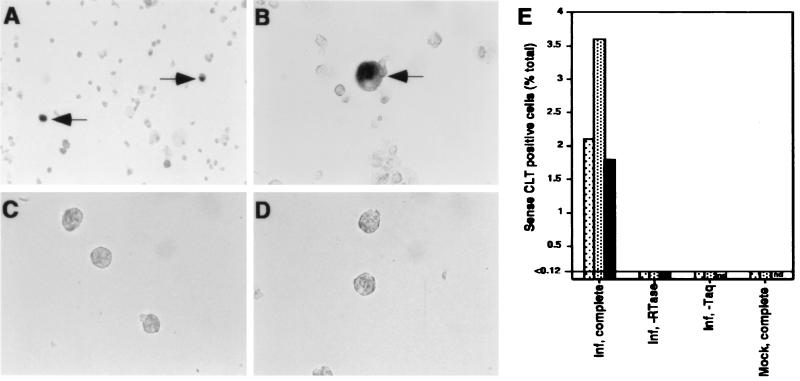

Viral transcripts expressed during experimental latent infection of GM-Ps and in BM mononuclear cells from healthy seropositive donors have been detected by solution RT-PCR analysis (9, 12, 13). We used RT-PCR-ISH to determine the number of cells expressing sense CLTs in a population of experimentally infected GM-Ps. Cultures were exposed to CMV RC256 at a MOI of 3, and 2 to 3 weeks after infection, nonadherent cells from three separate cultures were collected, treated with DNase, and subjected to RT with primer IEP2D. A total of 30 cycles of PCR amplification were performed with primers IEP2D and IEP1G. IEP1G lies upstream of the ie1/ie2 productive transcript start site within a region downstream of the latent start site such that amplification would be expected to occur from a latent but not a productive cDNA template. Amplified products were detected by ISH with a DIG-labelled riboprobe derived from pON2501 (Fig. 4). A small proportion of cells (1.8, 2.0, and 3.6%) from three independent cultures were positive for viral RNA. A signal was not detected in mock-infected cells, in virus-infected cells when either reverse transcriptase or Taq DNA polymerase was omitted (Fig. 4E), or when cells were pretreated with RNase (data not shown). These cultures were all negative for infectious virus and productive gene expression (data not shown), although more than 90% of cells were positive for viral DNA by PCR-ISH (Fig. 2). These data show that only a small proportion of viral genome-positive GM-Ps express detectable sense CLTs at a given time.

FIG. 4.

(A to D) Photomicrographs showing detection of sense CLTs by RT-PCR-ISH in experimentally infected GM-P culture. Infected cells were subjected to RT-PCR-ISH (A and B), with controls omitting reverse transcriptase (C) or Taq DNA polymerase (D). Sense CLT-positive cells are arrowed. Magnification, ×1,280 (A) and ×3,200 (B to D). (E) RT-PCR-ISH determination of the percentage of sense CLT-positive cells from three separate GM-P cultures 2 to 3 weeks after infection with RC256 at a MOI of 3. Virus-infected (Inf) or mock-infected (Mock) cells were analyzed in the presence of the full complement of reagents for sense CLT detection (complete) or with the omission of either reverse transcriptase (−RTase) or Taq DNA polymerase (−Taq). ⊡, experiment 1; , experiment 2; ■, experiment 3.

Quantitation of CMV genomes in naturally infected cells.

To assess the distribution of CMV DNA in cells from individuals undergoing natural latent infection, G-CSF-mobilized PB or BM samples were collected from 12 different autograft or allograft donors at the Stanford University Hospital Bone Marrow Transplantation Program. Autograft donors suffered from breast cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, or multiple myeloma, none of which are CMV associated, and allograft donors were all clinically healthy adults. Mononuclear cells were isolated without regard for their CMV serological status and subjected to PCR-ISH analysis. We were able to detect CMV DNA in a small percentage (0.004 to 0.01%) of mononuclear cells (Fig. 5A and C).Thus, viral DNA was found to be distributed in fewer than 1 in 104 mononuclear cells. In addition, there was no difference in the frequency of DNA-positive cells between the autograft and allograft donors examined, suggesting that latency in these two types of donors was not quantitatively different.

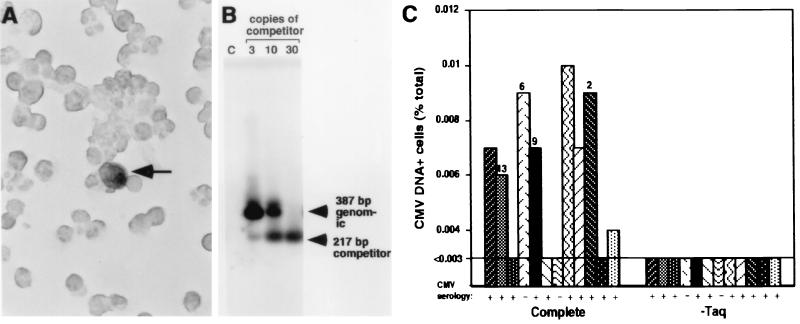

FIG. 5.

(A) Photomicrograph showing detection of CMV DNA in

naturally infected mononuclear cells by PCR-ISH. A CMV DNA-positive

cell is indicated by an arrow. Magnification, ×3,200. (B) CMV DNA copy

number determination by QC-PCR in G-CSF-mobilized PB cells from a

CMV-seropositive donor. Lysates of 5.4 × 104 cells

were each analyzed in the presence of 3, 10, or 30 copies of

competitive template, a CMV ie1/ie2 cDNA plasmid, pON2347.

The positions of the 387-bp product from CMV genomic DNA and the 217-bp

product from the cDNA competitive template are indicated by arrowheads.

A contamination control containing no DNA was included (lane c). (C)

PCR-ISH determination of the percentage of CMV DNA-positive mononuclear

cells from G-CSF-mobilized PB and BM autograft and allograft donors (12

donors were used altogether; see symbols below). Cells were analyzed in

the presence of the full complement of reagents for CMV DNA detection

(complete) or with the omission of Taq DNA polymerase

(−Taq). The number of CMV genomes per CMV DNA-positive cell was

determined by a combination of PCR-ISH and QC-PCR data and is shown as

numbers above the bars in the graph. Symbols:

, mobilized PB 1,

autograft;  ,

mobilized PB 2, autograft;

,

mobilized PB 2, autograft;

, mobilized PB 3,

autograft;

, mobilized PB 3,

autograft;  ,

mobilized PB 4, autograft; ■, mobilized PB 5, autograft; ▧,

mobilized PB 6, autograft;

,

mobilized PB 4, autograft; ■, mobilized PB 5, autograft; ▧,

mobilized PB 6, autograft;

, bone marrow 1,

autograft;

, bone marrow 1,

autograft;  ,

mobilized PB 7, allograft; ▨, mobilized PB 8, autograft;

,

mobilized PB 7, allograft; ▨, mobilized PB 8, autograft;

, mobilized PB 9,

autograft; ▩, mobilized PB 10, autograft;

, mobilized PB 9,

autograft; ▩, mobilized PB 10, autograft;

, mobilized PB 11,

allograft.

, mobilized PB 11,

allograft.

QC-PCR optimized to detect low genome copy numbers (3, 10, or 30 copies) was used to determine the viral genome copy number in lysates of 5.4 × 104 mononuclear cells from latently infected individuals. PCR amplification was performed for 40 cycles in these experiments, and a PCR contamination control lacking sample or competitor DNA was included in parallel. The products were resolved by electrophoresis on a 3% agarose gel, and amplified DNA was identified by DNA blot hybridization with 32P-labelled probe specific for amplified sequences. Both the 387-bp genomic and 217-bp competitor PCR products were detected (Fig. 5B) at a level indicating approximately 10 viral genomes per 5.4 × 104 cells. In this particular sample, 0.009% of the cells were viral genome positive, as determined by PCR-ISH (i.e., approximately 1 in 104 mononuclear cells was viral genome positive). To determine the number of viral genomes per CMV-positive cell in this sample, we divided the number of genome copies by the number of genome-positive cells and estimated that there were approximately two viral genomes per CMV-positive cell. An additional three samples were similarly analyzed, and the range of copy number estimates was 6, 9, and 13 copies per CMV DNA-positive cell (Fig. 5C). These results suggest that mononuclear cells from latently infected individuals contain relatively few viral genomes. We concluded that PCR-ISH and QC-PCR could be applied to naturally infected samples to determine both the number of CMV DNA-positive cells and the number of viral genomes harbored within those cells.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the latent human CMV genome is distributed at low copy numbers in a small proportion of mononuclear cells from latently infected individuals. PCR-ISH revealed viral genome-positive cells at a frequency of 0.004 to 0.01%. This small population of CMV-positive cells was present without significant variation in eight naturally infected individuals, suggesting remarkable consistency among the donors in whom the CMV genome was detected. Genome-positive cells were detected in mononuclear populations from 7 of 10 seropositive and 1 of 2 seronegative donors, with a detection limit of 1 positive cell in 3.3 × 104 total cells. The inability to detect genome-positive cells in all 10 seropositive donors probably reflects a frequency of latently infected cells in some of these donors which was below our limit of detection. The presence of genome-positive cells in 1 of 2 seronegative donors was not unexpected, because it has previously been reported that seronegative individuals are frequently CMV DNA positive in PCR (15, 29, 30). Although we detected viral genome-positive cells by PCR-ISH, we were unable to detect viral DNA in either experimentally infected GM-Ps or naturally infected mononuclear cells by conventional nonisotopic ISH (data not shown), consistent with a low abundance of viral genomes in these cells. By combining the detection of genome-positive cells by PCR-ISH and quantitation of viral genomes by QC-PCR, we were able to quantify the DNA load in latently infected cells during both experimental and natural infections. Our finding of viral genome copy numbers on the order of 1 to 13 genomes per CMV DNA-positive cell in both settings provides a validation of the experimental system and important new information on natural latent infection, since determination of the number of latently infected cells and the viral genome burden per infected cell have not been previously reported. Other studies have been limited to attempts at estimating the number of viral genomes in total cell or tissue samples (14, 25). Although we have not yet assessed whether naturally infected CMV genome-positive cells are resting or proliferating, the low copy number of viral genomes per cell found in mononuclear cells suggests that the virus is unlikely to be replicating productively in these cells and, as such, is unlikely to contribute to the establishment or maintenance phases of CMV latent infection.

The methods used here have relied upon PCR amplification of relatively small viral DNA fragments as an indicator of the presence of an intact genome. The recent demonstration by Bolovan et al. (3) that the latent CMV genome from naturally infected individuals has physical properties of a unit-length circle provides strong evidence that an intact CMV genome is carried by these cells. Although the establishment of latency and conformation of the viral genome both merit further investigation, it appears that a circular genome configuration of latent DNA is a conserved property of other herpesviruses (1, 5, 7). We have defined how CMV DNA is carried within PBMCs during latency. Similar approaches can now be applied to more accurately assess the distribution of CMV nucleic acids in transplant donors and recipients, a situation where the latent load and distribution may influence outcome. These are methods that can also be applied to validate data collected from experimental latency models of herpesviruses such as herpes simplex virus and Epstein-Barr virus.

CMV is notorious for reactivating under a wide range of circumstances that involve blood transfusion and organ transplantation (4). Measures of latency that have been applied to herpesviruses include determining the percentage of cells from naturally latent individuals that can be grown out or the percentage that can be shown to reactivate to productive replication during culture. The former method has long played a central role in our understanding of EBV latency, because latently infected B cells acquire the ability to outgrow normal B cells in culture (16) and the frequency of cells that grow out in culture is related to the numbers of PBMCs carrying latent DNA (23). CMV does not cause outgrowth of cells but can be reactivated. Soderberg-Naucler et al. (30) undertook an assessment of reactivation from naturally infected individuals, a procedure that had succeeded in the hands of only one other group over a 30-year period (6). In the recent study, CMV was estimated to reactivate from a small percentage of PBMCs following allogeneic stimulation, a range that is in agreement with the range of viral DNA-positive cells we detected by PCR-ISH in our study. Although reactivation from experimental human CMV latent infection of GM-Ps has been routinely achieved (9, 11), we have not yet successfully reactivated CMV from naturally infected samples to allow a more direct comparison of these two measures of viral latency.

Solution PCR of CMV nucleic acids has contributed to our understanding of latency in naturally infected individuals and has directed our attention to cells within the hematopoietic lineage, ranging from early BM-derived CD34+ progenitors (21) to lineage-committed CD33+ GM-dendritic cell progenitors (9, 11) and mature CD14+ PB cells (30, 34). CLTs were first identified in experimentally infected GM-Ps and have been detected in distinct subpopulations of mononuclear hematopoietic progenitor cells by solution RT-PCR (9, 11–13). Expression of latent transcripts was previously found to correlate with the presence of the myeloid lineage cell surface marker CD33, yet more primitive progenitors (CD34+ CD33−) and mature cells (CD15+ CD33−, CD14+ CD33−) were negative (9). In the present study, we were surprised to find that only a small percentage (2%) of CMV DNA-positive GM-Ps had detectable sense CLTs when subjected to RT-PCR-ISH analysis, because a majority of these cells are CD33+ (9, 11). The detection of CLTs in a minority of DNA-positive cells raises several possibilities: (i) sense CLTs may be expressed only in a subset of latently infected cells, (ii) sense CLT expression may correspond to some stage of latency, and (iii) CMV DNA-positive cells may include latently as well as abortively infected cells. Thus far, RT-PCR-ISH has failed to detect sense CLTs in total mononuclear cells from naturally infected individuals although sense CLTs have been detected at a frequency estimated to be less than 0.003% in pools of fluorescence-activated cell sorter-classified CD33+ cells by solution RT-PCR (9). Further evaluation of fluorescence-activated cell sorter-classified cell populations by RT-PCR-ISH and PCR-ISH will better define the relationship between RNA positive and genome-positive cells during natural latency. Although we may have underestimated the percentage of sense CLT-expressing cells due to limitations in the sensitivity of the RT-PCR-ISH assay, we were consistently able to apply this method to detect a majority of ie1/ie2 transcript-positive controls (data not shown). Our finding of a dissociation between the presence of viral genomes and latent gene expression has been reported for other herpesviruses (20, 22, 27), and we currently favor the possibility that the cell type, cell activation state, or stage of latency may dictate whether sense CLTs are expressed. Thus, the percentage of cells in GM-P cultures expressing sense CLTs may reflect differentiation or cell cycle state, a situation that is most analogous to Epstein-Barr virus, where not all latent gene products are expressed all the time (22). The fact that sense CLT expression seems to be associated with the myeloid progenitor cell surface marker CD33 (9) already suggested that cell state might have a significant effect on expression. We expect that direct evaluation of CMV mutants that are defective in latent gene expression will reveal any role these products play in latency, including establishment, maintenance, and reactivation phases.

Our work demonstrates that the CMV genome can be detected and quantitated directly in naturally infected populations. The in situ detection and quantification methods used here will enable a more detailed analysis of the distribution of latent viral genomes and transcripts in different cell populations. Although the serologic status and state of immunosuppression of the donor and recipient have been shown to contribute to the risk of CMV-associated disease during the posttransplantation period (4), the number of viral genomes transferred in donor material might also be an important risk factor in blood cells transferred with organ transplants (14, 18). The assessment of patterns of CMV latency in donor cells with respect to genome distribution, number, and transcriptional activity may provide a rational basis for a more detailed assessment of risk factors associated with the transmission and reactivation of CMV in allograft recipients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Stanford University Hospital Bone Marrow Transplantation Program for donor samples, Kirsten Lofgren for assistance with collection of liver samples, and Allison Abendroth for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health (RO1 AI33852 and PO1 CA49605). For a portion of this work, B.S. was supported by a research fellowship from the American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams A, Lindahl T. Epstein-Barr virus genomes with properties of circular DNA molecules in carrier cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1477–1481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevan I S, Walker M R, Daw R A. Detection of human cytomegalovirus DNA in peripheral blood leukocytes by the polymerase chain reaction. Transfusion. 1993;33:783–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33994025030.x. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolovan-Fritts C A, Mocarski E S, Weideman J A. Peripheral blood CD14+cells from healthy subjects carry a circular conformation of latent cytomegalovirus genome. Blood. 1999;93:394–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britt W J, Alford C A. Cytomegalovirus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2493–2523. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker L L, Klaman L D, Thorley-Lawson D A. Detection of the latent form of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the peripheral blood of healthy individuals. J Virol. 1996;70:3286–3289. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3286-3289.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diosi P, Moldovan E, Tomescu N. Latent cytomegalovirus infection in blood donors. Br Med J. 1969;4:660–662. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5684.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garber D A, Beverley S M, Coen D M. Demonstration of circularization of herpes simplex virus DNA following infection using pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Virology. 1993;197:459–462. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haase A T, Retzel E F, Staskus K A. Amplification and detection of lentiviral DNA inside cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4971–4975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn G, Jores R, Mocarski E S. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3937–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komminoth P, Long A A, Ray R, Wolfe H J. In situ polymerase chain reaction detection of viral DNA, single-copy genes, and gene rearrangements in cell suspensions and cytospins. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1992;1:85–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo K, Kaneshima H, Mocarski E S. Human cytomegalovirus latent infection of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11879–11883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo K, Mocarski E S. Cytomegalovirus latency and latency-specific transcription in hematopoietic progenitors. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1995;99:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kondo K, Xu J, Mocarski E S. Human cytomegalovirus latent gene expression in granulocyte-macrophage progenitors in culture and in seropositive individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11137–11142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotsimbos A T, Sinickas V, Glare E M, Esmore D S, Snell G I, Walters E H, Williams T J. Quantitative detection of human cytomegalovirus DNA in lung transplant recipients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1241–1246. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.4.96-09106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson S, Soderberg-Naucler C, Wang F Z, Moller E. Cytomegalovirus DNA can be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from all seropositive and most seronegative healthy blood donors over time. Transfusion. 1998;38:271–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38398222871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewin N, Aman P, Masucci M G, Klein E, Klein G, Oberg B, Strander H, Henle W, Henle G. Characterization of EBV-carrying B-cell populations in healthy seropositive individuals with regard to density, release of transforming virus and spontaneous outgrowth. Int J Cancer. 1987;39:472–476. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long A A, Komminoth P, Lee E, Wolfe H J. Comparison of indirect and direct in-situ polymerase chain reaction in cell preparations and tissue sections. Detection of viral DNA, gene rearrangements and chromosomal translocations. Histochemistry. 1993;99:151–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00571876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry R W, Adam E, Hu C, Kleiman N S, Cocanougher B, Windsor N, Bitar J N, Melnick J L, Young J B. What are the implications of cardiac infection with cytomegalovirus before heart transplantation? J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13:122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maples J A. A method for the covalent attachment of cells to glass slides for use in immunohistochemical assays. Am J Clin Pathol. 1985;83:356–363. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/83.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta A, Maggioncalda J, Bagasra O, Thikkavarapu S, Saikumari P, Valyi-Nagy T, Fraser N W, Block T M. In situ DNA PCR and RNA hybridization detection of herpes simplex virus sequences in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected mice. Virology. 1995;206:633–640. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendelson M, Monard S, Sissons P, Sinclair J. Detection of endogenous human cytomegalovirus in CD34+ bone marrow progenitors. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:3099–3102. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-12-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyashita E M, Yang B, Babcock G J, Thorley-Lawson D A. Identification of the site of Epstein-Barr virus persistence in vivo as a resting B cell. J Virol. 1997;71:4882–4891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4882-4891.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyashita E M, Yang B, Lam K M, Crawford D H, Thorley-Lawson D A. A novel form of Epstein-Barr virus latency in normal B cells in vivo. Cell. 1995;80:593–601. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mocarski E S. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2447–2492. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer P, Braun R W, Mohring K, Henco K, Kang J, Wendland T, Kuhn J E. Quantitative determination of human cytomegalovirus target sequences in peripheral blood leukocytes by nested polymerase chain reaction and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2699–2707. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-12-2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sindre H, Tjoonnfjord G E, Rollag H, Ranneberg-Nilsen T, Veiby O P, Beck S, Degre M, Hestdal K. Human cytomegalovirus suppression of and latency in early hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;88:4526–4533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slobedman B, Efstathiou S, Simmons A. Quantitative analysis of herpes simplex virus DNA and transcriptional activity in ganglia of mice latently infected with wild-type and thymidine kinase-deficient viral strains. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2469–2474. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slobedman B, Simmons A. Concatemeric intermediates of equine herpesvirus type 1 DNA replication contain frequent inversions of adjacent long segments of the viral genome. Virology. 1997;229:415–420. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith K L, Kulski J K, Cobain T, Dunstan R A. Detection of cytomegalovirus in blood donors by the polymerase chain reaction. Transfusion. 1993;33:497–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33693296813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soderberg-Naucler C, Fish K N, Nelson J A. Reactivation of latent human cytomegalovirus by allogeneic stimulation of blood cells from healthy donors. Cell. 1997;91:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spaete R R, Mocarski E S. Insertion and deletion mutagenesis of the human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7213–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanier P, Taylor D L, Kitchen A D, Wales N, Tryhorn Y, Tyms A S. Persistence of cytomegalovirus in mononuclear cells in peripheral blood from blood donors. Br Med J. 1989;299:897–898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6704.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons J G, Borysiewicz L K, Sinclair J H. Monocytes are a major site of persistence of human cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:2059–2064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-9-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons P, Sinclair J. Induction of endogenous human cytomegalovirus gene expression after differentiation of monocytes from healthy carriers. J Virol. 1994;68:1597–1604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1597-1604.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]