Abstract

Despite a significant accumulation of research, there has been little systemic implementation of evidence-based practices (EBP) in youth mental health care. The fragmentation of the evidence base complicates implementation efforts. In light of this challenge, we sought to pilot a system that consolidates and coordinates the entire evidence base in a single direct service model (i.e., Managing and Adapting Practice; MAP) in the context of a legal reform of psychotherapy training in Germany. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of the implementation of MAP into the curriculum of the reformed German master's program. Eligible participants were students in the master’s program at Philipps-University Marburg during the winter-term 2022/2023. Students first learned about MAP through introductions and role plays (seminar 1), followed by actively planning and conducting interventions using MAP resources for patients in a case seminar under supervision (seminar 2). A repeated-measures survey was conducted to investigate students’ knowledge gains, perception of MAP and changes in their self-rated confidence to use EBP. Results indicated that students perceive MAP to be manageable to learn. Positive progress was achieved with regard to their knowledge and self-reported confidence to use EBP, although interpretation and generalization of the results are limited by small and homogeneous samples, lack of statistical power and missing comparison groups. The feasibility of the implementation and suitability of measures are discussed. Important implications could be drawn with regard to future investigations.

Keywords: Implementation, Evidence-based practice, Mental health care, Children and adolescents, Psychotherapy training

Subject terms: Paediatric research, Translational research, Health services

Introduction

With a growing number of global crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, war, hunger and accompanying refugee movements, the mental health burden on young individuals and the need for professional mental health care for children and adolescents worldwide is rising1,2. To meet this growing demand, pragmatic and effective interventions need to be implemented within the health care system while remaining easily accessible for both patients and providers. In the last decades, psychotherapy research demonstrated that evidence-based practices (EBP) show advantages like higher effect sizes compared with usual care3,4 as well as increased cost-effectiveness5–7. EBP are defined as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values”8,9. They are required to monitor the effectiveness or potential harms of interventions during treatment and to be “consistently science-informed, organised around client intentions, [and] culturally sensitive”10.

Despite a significant accumulation of research11, EBP are not widely represented in mental health care12,13, and there has been little systemic implementation of EBP for youth in mental health care systems. Implementation efforts are complicated by the rapid growth of specific evidence-based interventions and the accompanying fragmentation of the evidence base, i.e. the large number of study results that only apply to single interventions. The wealth of options that are essentially “non-interoperable” typically requires practitioners to learn a large number of independent interventions in order to manage a typical caseload14. Accordingly, extracting core practices and process models (e.g., overlapping practice elements) of various evidence-based interventions15,16 enables one to scale up EBP by enabling practitioners to engage in a harmonized, transdiagnostic, responsive approach to evidence-based intervention, with a manageable amount of workforce development activity that can be paced over time17,18. Moreover, this individualized approach addresses the frequently discussed challenge that EBP are not suitable to a range of patients, especially in case of comorbidity, resulting in low response rates11,19. Individualized approaches are characterized by tailoring and adapting psychotherapy to specific patient characteristics and situations in addition to their disorders in order to enhance treatment effectiveness20. Indeed, they have been shown to outperform usual care21 as well as “gold standard” evidence-based treatment3,22.

Managing and Adapting Practice (MAP) is a system that consolidates and coordinates the entire youth mental health evidence base within its direct service model. In distinction to individual EBP, MAP provides a framework, concepts and diverse resources to help providers to identify and select, personalize, implement and evaluate modular transdiagnostic interventions based on the research evidence23. MAP resources include the PracticeWise Evidence-Based Services Database (PWEBS), the Practitioner Guides summarizing either common procedures among evidence-based practices (Practice Guides) or frameworks for organizing service delivery (Process Guides), and Clinical Dashboards, Microsoft Excel™ based tools to visualize the treatment plan, process and progress23. The PWEBS database enables providers to search within a database of coded randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of youth interventions. Updates to the database are derived from two main sources: ongoing literature searches conducted by PracticeWise, and RCTs nominated by researchers, and community partners24. Users can customize their PWEBS search to retrieve evidence-based interventions that align with the individual youth’s problem area and characteristics. To provide a comprehensive overview of the results, the treatment families, practice elements, setting and format of the interventions are displayed with their frequencies in the available studies. Previous studies in Minnesota25 and Los Angeles26,27 demonstrate the instructional efficacy of the MAP system as well as its effectiveness in achieving large-scale and rapid implementation with considerable evidence of sustainability28. This might be due to the higher therapist satisfaction with and acceptance of MAP29,30.

Moreover, evaluations on youth outcomes of MAP implementation are promising. Southam-Gerow et al.26 report effect sizes ranging from d = 0.59 to d = 0.80 on a caregiver report measure of emotional and behavioral problems before and after MAP interventions. The modular approach to therapy for children with anxiety, depression, trauma, or conduct problems (MATCH-ADTC)31 is a specific intervention protocol designed using practice coding of four EBP as well as the MAP architecture and concepts. The intervention is comprised of 33 treatment components that are frequently included in well-supported EBP to address youth anxiety, depression, trauma and conduct problems. Comprehensive flowcharts are provided to guide the selection and arrangement of therapy procedures and step-by-step instructions facilitate the implementation of treatment components. Concurrently, service providers are supported to individualize interventions and address comorbidity and treatment interferences31. When compared with a county-supported implementation of multiple evidence-based practices for youth, MATCH-ADTC resulted in faster and greater improvement for children than receiving standard EBP. Moreover, the children in the MATCH-ADTC treatment condition were less likely to receive additional psychosocial treatment services or psychotropic medications22. Recently, an adapted MATCH-ADTC intervention for children with epilepsy was evaluated in an RCT in the UK and was found superior to assessment-enhanced usual care regarding the reduction of emotional and behavioural difficulties32.

In Germany, MAP is familiar only among youth mental health researchers and essentially unknown within routine practice providers or service organizations. Recently, the psychotherapy training for state-licensed professional psychotherapists began to undertake major changes aiming to foster the scientist-practitioner approach. Based on a federal legal reform, more competency-based courses and practice components are included in the university curricula to obtain the master’s degree in clinical psychology and psychotherapy. With the current educational changes comes an opportunity to contribute to the dissemination and implementation of EBP in the German mental health system. Therefore, we aim to implement MAP into the German healthcare system by incorporating it into two modules of the reconceptualized master’s degree program of clinical psychology and psychotherapy, with a total of 3 courses and 8.5 credits. Our pilot study explored the feasibility of implementing MAP in everyday university settings in Germany. We first focused on our students’ reception and perception of MAP, as feedback from future providers’ (i.e., the students) is indispensable to achieve sustainable implementation33. The development of students’ (self-)confidence in using EBP is a key concern across the different courses. Besides, we also aimed to monitor the quality of our teaching through effects on students' knowledge. The pilot study should inform us whether the evaluation design and its instrumentation by means of the selected questionnaires is suitable to monitor the teaching concept and the implementation of MAP. Accordingly, we aimed to draw practical implications from our pilot study for the future implementation of MAP in the German education and health care system and its empirical investigation.

Methods

MAP implementation

The two seminars of interest focus on training students in evidence-based psychotherapy intervention practices for children and adolescents. They consist of a first seminar with theory-based instruction of the evidence based, modular treatment approach MAP with role play practices on the interventions learned; and a second seminar enabling the application of the approach in a case class, where the students treat a group of patients under continuous live supervision by a licensed psychotherapist.

(1) Seminar 1 started with an introduction to MAP in general with the opportunity for students to ask questions or discuss concerns. After rehearsal of MAP concepts and resources, the students practiced several interventions from the MAP Practitioner Guides portfolio in role plays (small groups of 3 to 4 students) which were supervised by a MAP instructor. Those interventions were picked as they address central foci of child and adolescent psychotherapy both from the perspective of the child/youth and the parents. Also, the introduced practice guides represent basic interventions in child and adolescent psychotherapy, which is why they are especially helpful for early professionals. Further, demonstrating how to self-learn and then to use those interventions is essential for future practice, as psychotherapists are required to continuously update their knowledge and practices. All concepts, resources and applications covered in seminar 1 are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of MAP curriculum components adapted from Becker et al., 2022.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Concepts | |

| Evidence-based services system model | Model to guide service planning and delivery with consideration and coordination of multiple sources of evidence |

| The CARE Processa | Problem solving process of evaluating central questions, considering individual evidence, implementing identified solutions and evaluating the responses |

| Connect-Cultivate-Consolidate | Coordination of interventions across treatment phases |

| Focus-Interference Framework | Differentiation of prioritized treatment targets and anticipated interferences |

| Treatment planner | Creating a treatment plan by considering Connect-Cultivate-Consolidate and Focus-Interference |

| Session planner | Coordination of pre- and post-session activities |

| Resources | |

| PWEBS Database | Synthesis of research results on effective interventions, searchable with user-defined parameters (e.g., youth characteristics) |

| Clinical Dashboards | Progress monitoring system with case information, planned and implemented interventions and session feedback |

| Practice Guides | Summaries to guide the performance of common clinical interventions |

| Therapist portfolio | System to monitor the MAP learning progress |

| Applications | |

| Assessment | Generating case-specific evidence by considering multiple measures across multiple domains |

| Monitoring | Monitoring session-wise outcomes and feedback to compare the expected and actual progress |

| Planning | Planning interventions based on the case-specific information and evidence base |

| Practice delivery | Rehearsal and actual delivery of interventions |

| MAP system | Systematic and collaboration of MAP components |

Notes. MAP, Managing and Adapting Practice; PWEBS , PracticeWise Evidence-based Services Database; CARE, Consider, answer, respond, evaluate.

aThis component was only conducted in two courses.

(2) Seminar 2 was completed in a high frequency day format setting within one week (five days with interventions from 9:30 am to 3:30 pm and preparation from 9:00 to 9:30 am and 3:30 to 6:00 pm each day) in the outpatient clinic for child and adolescent mental health care of Philipps-University Marburg, Germany. Students planned and conducted psychotherapy sessions under live supervision by licensed therapists for a group of patients (overall 4 classes with 13–16 students each and 3–5 children treated per class). Patients presented with various mental health disorders, for example attention deficit/hyperactivity or anxiety disorders. The interventions were planned with the help of the MAP resources (for example a PWEBS search) and conducted with the support of the Practitioner Guides as covered in seminar 1. Students created Clinical dashboards to evaluate the treatment progress.

Pre-piloting

In winter-term 2021/22, we conducted a very first MAP implementation, evaluated students’ views on MAP and considered their verbal feedback to plan the current pilot study. In the following, we describe the adaptations that were made based on the pre-piloting.

Pre-piloting the implementation

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, seminar 1 was conducted asynchronously as well as synchronously online over the semester in winter-term 2021/22. It was based on a flipped classroom concept. Accordingly, the students prepared central MAP concepts or resources by working independently and asynchronously through the MAP online training modules. In synchronous online appointments, the contents were rehearsed and interventions were rehearsed in role-plays.

In winter-term 2022/23, all appointments took place on-site rather than online, and students received more guidance. In addition, different training formats for seminar 1 were tested: While a large part of the students received a four-day intensive training, for one group of 15 students, seminar 1 was conducted over the semester. This was due to university requirements for the organization of teaching. Moreover, the German education team was supported and counseled by PracticeWise professionals in teaching a class of 49 students. Besides supervising the classes and checking the alignment with standardized PracticeWise teaching, they provided feedback on the clinical dashboards that students created in seminar 2.

Pre-piloting the evaluation

In our first evaluation in winter-term 2021/22, a total of 13 assessments were conducted to assess progress and changes during seminar 1 and 2. Besides students’ providing information on demographics and training, the following instruments were used: Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale (PCIS)34, Evidence Based Practice Attitudes Scale (EBPAS-36D)35,36, Adaptations to Evidence-Based Practices Scale (AES)37. In addition, students rated their agreement on visual analogue scales (VAS) providing global assessments (1) on their confidence to use EBP with six questions and (2) on their contentment with the implementation of specific interventions and adherence to MAP Practitioner Guides with six questions. The students expressed concern about the time and effort involved in this survey procedure. In addition, some of these instruments turned out to be inadequate or unsuitable during our pre-piloting, namely the PCIS subscales Relative advantage, Compatibility, Trialability, Observability and Task issues, the AES and the VAS on MAP implementation. This will be elaborated in more detail in the discussion section.

Accordingly, we applied a reduced survey procedure in winter-term 2022/23 with only two assessments to capture changes during seminar 2 (before and after the last day). In addition, based on the feedback of the PracticeWise professionals and in order to obtain more comprehensive data pertaining to the acquisition of knowledge and skills, we piloted knowledge assessments pre-post to the introduction of new topics in seminar 1. The 50 knowledge questions were provided by PracticeWise for research purposes and cover knowledge about the MAP system and concepts, and interventions to treat depression, anxiety, traumatic stress and disruptive behavior in youth.

Ethics

The Internal Review Board of the Philipps-University Marburg approved the evaluation (approval number: 2021-73k). All methods were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines. Except for the knowledge tests, participants received full study information and provided written informed consent before they were able to access the survey. Each participant created an individual code based on letters and numbers to enable repeated measurements with anonymously collected data. All raw data were stored securely at the Department of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology at Philipps-University Marburg, Germany.

Participants

Eligible participants were first-year students enrolled in the reconceptualized master’s program in clinical psychology and psychotherapy of Philipps-University Marburg, Germany during the winter-term 2022/23. All students were required to complete the two seminars of interest as part of the module on professional qualification (in German: Berufsqualifizierende Tätigkeit, BQT-II) aligning to state license requirements formulated in the reformed psychotherapy law. No exclusion criteria were applied.

A total of 83 students were eligible participants. An anonymous sample of N = 80 (96.39%) completing seminar 1 participated in the knowledge assessments. We refrained to assess any personal and potentially identifying information in addition to the knowledge tests as not to pressure students.

Of the 83 students in seminar 1, n = 57 were randomly assigned to participate in seminar 2 in the same winter term. Please note that due to organizational constraints, only 60 places are available to students in seminar 2 at the end of a winter term. A further 30 places are only available to students at the end of the summer term. An employee of the organisation team, who was not informed about our survey and its objectives, was responsible for allocating places by lottery to students who would complete seminar 2 in the winter and summer semesters. Of those 57 students a sample of N = 36 (63.16%) completed the first evaluation on seminar 2 (assessment 9). Further details on these participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample description.

| N/M | %/SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Eligible students | 57 | 100.00 |

| Participating students | 36 | 63.16 |

| Age | 23.14 | 1.25 |

| Range | 20–26 years | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 34 | 94.40 |

| Male | 1 | 2.80 |

| Diverse | 1 | 2.80 |

| Practical clinical experience (e.g., due to internships) | ||

| None | 0 | 0.00 |

| Up to 3 months | 16 | 44.40 |

| 4–6 months | 16 | 44.40 |

| 7–9 months | 2 | 5.60 |

| 10–12 months | 1 | 2.78 |

| More than 12 months | 1 | 2.78 |

A total of n = 13 (22.81%) completed the second evaluation (assessment 10) after seminar 2. No significant differences were found between students that completed both assessments and those that only completed the first evaluation regarding their age (U = 144.50, p = 0.871), confidence in using EBP (U = 123.50, p = 0.397), PCIS subscales Complexity (U = 58.00, p = 0.999), Potential for reinvention (U = 20.00, p = 0.397), Nature of knowledge (U = 28.00, p = 0.059), and Technical support (U = 49.00, p = 0.999) and EBPAS-36D (U = 98.00, p = 0.535) at the first evaluation.

Data collection

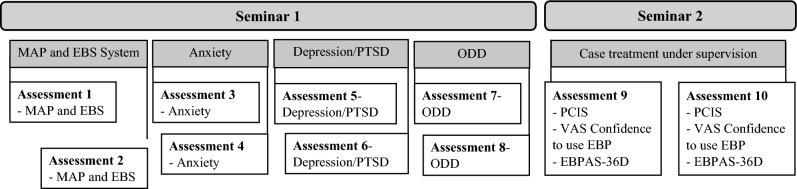

Repeated measures data were collected via an openly accessible online survey, using the scientific survey platform SoSci Survey (www.soscisurvey.de). The link was distributed via e-mail to all eligible participants. Participation was voluntary without compensation for students’ efforts. Figure 1 displays the data collection procedures.

Figure 1.

Flow charts of the assessments. Notes. EBP, Evidence Based Practices; EBPAS-36D, Evidence Based Practice Attitudes Scale; PCIS, Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale; PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Measures

Knowledge tests

50 standardized knowledge items from PracticeWise were used to assess students’ knowledge of MAP and the EBS system and the treatment of specific mental disorders (i.e., depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, trauma disorders, and disruptive disorders) in children and adolescents. Items were questions with four to five answers of which one right answer had to be chosen. Individuals’ scores can have values ranging from 0 to 100 in increments of ten, representing the percentage of correct answers.

Demographics and information on training

Participants provided standard demographic and training information (e.g., age, semester) in the first survey of seminar 2.

Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale (PCIS)

The PCIS subscales Complexity, Potential for reinvention, Nature of knowledge and Technical support were used to evaluate students’ views on MAP (see Fig. 1). The PCIS was developed by Cook, Thompson and Schnurr34 to assess health care providers’ views of interventions. The authors found it to be a reliable measure of perceived characteristics of particular evidence-based treatments for mental health care. Respondents are asked to rate their agreement with statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘a very great extent’). All items are worded in such a way that higher scores indicate more positive evaluations of the intervention. The items load on subscales with two items each34: The subscale Complexity (internal consistency in the current sample: α = 0.37) assesses the level of difficulty to understand and use the innovation and the subscale Potential for reinvention (α = 0.87) the ability to refine, elaborate and modify the innovation. The subscale Nature of knowledge (α = 0.91) captures the amount of knowledge and skills that are required to implement the innovation and the subscale Technical support (α = 0.91) inquires whether the manual or material is helpful. The German translation of the PCIS can be found in Table S1 in Supplemental material 1.

Global assessments on confidence to use EBP

Students rated their own confidence and competence in using EBP on visual analogue scales (from 1 to 101) for six questions, e.g. ‘To what extent do you feel confident in using EBP?’ Since the total scale shows good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha α = 0.92-0.98 in the current sample, a composite mean score was calculated. Higher scores indicate greater confidence. All items can be found in Table S2 in Supplemental material 1.

Evidence Based Practice Attitudes Scale (EBPAS-36D)

The EBPAS-36D was used to assess students’ attitudes toward adopting EBP. The German translation of the EBPAS-3634 has been psychometrically investigated in a German-speaking sample of mental health care providers36. The 36 items assess positive attitudes toward EBP (e.g., their fit with values and needs of providers and patients) as well as ambivalent attitudes (e.g., the burden of learning EBP). Respondents are asked to rate their agreement with statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘to a very great extent’). Most items are worded in such a way that a higher total score indicates a more positive attitude towards the adoption of EBP; 15 items are scored reversely. A mean of the subscales can be computed to create a total scale (internal consistency in the present sample at the first assessment: α = 0.88).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 28.0.1.1 for Windows (Chicago, IL, USA). To obtain internal reliability coefficients of the scales and subscales, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. Values above 0.70 are regarded as acceptable, higher than 0.80 as good, higher than 0.90 as excellent. Nonparametric tests were used due to lack of normal distributions and small sample sizes. Mann–Whitney-U-Tests were used to assess differences between participants that answered both surveys on seminar 2 and those that dropped out. Wilcoxon-tests for paired samples were used to investigate changes from before to after seminar 1 and before to after seminar 2. P values < 0.05 were set as thresholds for statistical significance.

Regarding the knowledge changes, we first evaluated differences in the knowledge scores before vs. after seminar 1. In the following, we compared the three separate seminar groups: one group that received a four day intensive training with support of international PracticeWise professionals (high frequency with counseling, n = 49), one group that received one-week intensive training by our German team alone (high frequency, n = 15) and the last group that visited seminar 1 over the course of the semester, also conducted by the German team (low frequency, n = 15). As changes in students’ perceptions of MAP and their knowledge were investigated with four subscales each, we corrected the alpha level using the Bonferroni procedure (α = 0.013) for these analyses to reduce the risk of familywise error due to multiple testing.

Ethics approval statement

The Internal Review Board of the Philipps-University Marburg approved the first evaluation (approval number: 2021-73 k).

Participant consent statement

Except for the knowledge tests, participants received full study information and provided written informed consent before they were able to access the survey.

Results

Knowledge

When comparing students’ scores on the knowledge tests before and after training days of seminar 1, significant differences were found regarding students’ knowledge of MAP and the EBS system; Z = − 6.12; p < 0.001; anxiety disorders; Z = − 5.37; p < 0.001; posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and depression; Z = − 4.44; p < 0.001; and oppositional defiant disorders (ODD); Z = − 7.35; p < 0.001 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Wilcoxon-tests for paired samples (seminar 1).

| Total sample (N = 79) | High frequency with counseling (n = 49) | High frequency (n = 16) | Low frequency (n = 15) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge tests | Z | p | Z | p | Z | p | Z | p |

| MAP and EBS systemb | − 6.12 | < 0.001* | − 5.44 | < 0.001* | − 3.22 | < 0.001* | − 0.95 | 0.362 |

| Anxietyb | − 5.37 | < 0.001* | − 4.50 | < 0.001* | − 2.49 | 0.018 | − 1.81 | 0.090 |

| PTSD and Depressionb | − 4.44 | < 0.001* | − 2.07 | 0.039 | − 3.33 | < 0.001* | − 2.50 | 0.013 |

| ODDb | − 7.35 | < 0.001* | − 5.87 | < 0.001* | − 2.72 | 0.005* | − 3.47 | < 0.001* |

Notes. bBonferroni-adjusted α = 0.013.

*Significant result of two-sided exact test.

For the high frequency group with counseling, significant differences between the knowledge scores before and after the seminar emerged for the MAP and EBS system, anxiety disorders and ODD, but not for PTSD and depressive disorders; Z = − 2.07, p = 0.039. For the high frequency group without counseling, significant differences between the knowledge scores before and after the seminar emerged for the MAP and EBS system, PTSD and depressive disorders and ODD, but not for anxiety disorders; Z = − 2.49, p = 0.018. For the low frequency group, significant differences between the knowledge scores before and after the seminar emerged only for ODD, but not for the MAP and EBS system, PTSD and depressive disorders and anxiety disorders (see Table 3).

Evaluation of MAP

Characteristics of MAP were rated as acceptable at the start of seminar 2 with M = 3.80 (SD = 0.63) on the PCIS subscale Complexity, M = 4.13 (SD = 0.79) on the PCIS subscale Potential for reinvention, M = 3.64 (SD = 0.76) on the PCIS subscale Nature of knowledge and M = 3.48 (SD = 1.09) on the PCIS subscale Technical support. They remained stable during seminar 2 as no significant differences emerged comparing scores before and after the seminar (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Wilcoxon-tests for paired samples (Pre/post) for Seminar 2.

| Scale | Z | Two-sided exact p |

|---|---|---|

| PCIS Subscales | ||

| Complexityb | − 0.32 | 0.844 |

| Potential for reinventionb | − 1.30 | 0.375 |

| Nature of knowledgeb | − 2.06 | 0.063 |

| Technical supportb | − 0.11 | 0.938 |

| Visual analogue scale | ||

| Confidence to use EBP | − 2.76 | 0.003* |

Notes. PCIS, Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale; EBP, Evidence-based practices.

bBonferroni-adjusted α = 0.013.

*Significant result.

Confidence in using EBP

Significant higher scores were reached after seminar 2 compared to before; Z = − 2.76, p = 0.003; indicating increasing confidence in students’ EBP use.

Attitudes towards EBP

Students reported moderate attitudes towards EBP on the EBPAS-D36, M = 2.92 (SD = 0.27). No significant changes emerged between their ratings before and after seminar 2; Z = 35.50, p = 0.824.

Discussion

The present study aimed to pilot the implementation of MAP into the reformed master’s degree program in clinical psychology and psychotherapy in Germany and to evaluate the feasibility of our study design and methods. To discuss our results, we will first discuss our implementation procedures and results on students’ knowledge changes, evaluation of MAP, and confidence in using EBP. Thereafter, results on the feasibility of research methods are discussed and lessons learned are summarized. After reviewing major limitations of our pilot study, we aim to conclude practical implications for the future implementation of MAP in the German educational and health care system.

Lessons learned on the MAP implementation

The first cohorts of students at Philipps-University Marburg completing the BQT-II module of the reconceptualized master’s program were instructed in the use of MAP, first through theoretical seminar content and role plays in small groups (seminar 1), and finally by planning and conducting interventions for a group of patients in a case seminar under supervision (seminar 2).

To capture the quality of our teaching, students answered knowledge tests before and after class. The results indicate an increase in expertise. Hereby, we compared three different training formats (high frequency with counseling, high frequency and low frequency). Although the results should be interpreted with caution due to the small and very different sample sizes across the training conditions, it seems that carrying out the seminar over the course of the semester was inferior to a high frequency format. Until now, few studies have evaluated the optimal approaches of therapist trainings to implement EBP. One systematic review indicates that more intensive training approaches that go beyond provision of manuals and brief workshops but provide additional components like consultation are more effective38. However, the optimal number, duration and spacing of training sessions requires further investigation. As Henrich, Glombiewski and Scholten39 point out, the distribution of sessions over a longer period of time might allow therapists to expand and consolidate the acquired skills by applying them in their clinical practice between sessions.

Students in our pilot study evaluated the MAP system as quite understandable, easy to use and manageable to learn as well as equipped with helpful materials. Thus, it can be assumed that the students felt capable of learning contents and competencies they assumed to be important for the implementation of MAP. The average ratings were comparable to those reported by Cook et al.34 and Stadnick et al.40. Encouragingly, it appeared that students’ confidence in being able to use EBP increased during seminar 2. This is of relevance as results of previous studies indicate that practitioners’ self-rated confidence, competence or perceived behavioral control to use EBP predicts their intention or actual use of interventions41,42. At the same time, research evidence indicates that therapists tend to overestimate their interventions’ effectiveness43, and have limited competencies to predict negative treatment outcomes44,45. Accordingly, education in the master’s program of clinical psychology and psychotherapy should aim to enhance students’ perceived capability to implement EBP while at the same time improving their ability to anticipate adverse treatment processes in order to make adjustments. Continuous progress and outcome monitoring during treatment and the collaborative evaluation of the data with supervisors is not yet common practice, but would likely improve patient outcomes46,47. As a result of such positive processes, practitioners’ perceived confidence can presumably be enhanced as well.

To summarize, the implementation of MAP into the reformed master's degree program in clinical psychology and psychotherapy is feasible. Students’ valuable feedback will hopefully help us to enhance their skill building and implementation sustainment. In the future, students’ abilities to monitor treatment processes might be encouraged by incorporating client and supervisor feedback.

Lessons learned on the implementations’ evaluation

Another goal of our pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility of the study design and the suitability of measures in the target group. Major difficulties emerged with regard to the measures already during our pre-piloting. The majority of the available instruments usually used in dissemination research seemed unsuitable for our context, which did not involve the implementation of specific, manualized EBP. These are important observations, given that one goal of our pilot implementation study was to determine which measures might be appropriate for a larger implementation evaluation (see48).

Firstly, the PCIS subscales Relative advantage, Compatibility, Trialability, Observability and Task issues revealed to be inadequate as they expect a comparison with the usual practical activity or other treatments. Understandably, our students gave us the feedback that they do not have enough practical experience that would allow these comparisons. Internal consistencies of the subscales indicate inadequate reliability, perhaps due to the limited ability of students to provide answers. The remaining four subscales Complexity, Potential for reinvention, Nature of knowledge and Technical support seemed applicable. Moreover, we consider these scales to be relevant, as they map some of the benefits or potential drawbacks that users might consider when deciding whether they apply MAP to their therapeutic service. However, it should be noted that the subscale Complexity showed low internal consistency in the current sample and should be interpreted with caution.

Secondly, the EBPAS-36D that we used to assess students’ attitudes towards EBP must be critically reflected. Although the EBPAS-36 is a highly relevant instrument for implementation science with good psychometric properties35, its definition of EBP and associated advantages and disadvantages fits better with specific and often manualized interventions than with the flexible and modularized application of MAP as a comprehensive system. Some of the items therefore seem inappropriate to capture attitudes towards the use of MAP or modularized psychotherapy, for example “Clinical experience is more important than using manualized therapy/treatment”. Modifications may allow capturing attitudes toward modularized psychotherapy and MAP49,50. This causes ambiguity since reservations about manualized EBP may indicate a preference for the modularized approach in MAP. The Modified Practice Attitude Scale (MPAS,49) might represent an alternative to the EBPAS being a revised version without referencing “manualized” interventions.

Thirdly, we used the AES in our pre-piloting to assess adaptations that were made by the student groups when implementing MAP during practical training in seminar 1 and seminar 2. The AES might be used to capture providers’ “adherence” to a manualized treatment protocol, with fewer adaptations ascribed to a more adherent, more desirable behavior. Usually, adjustments to the practical approach would be considered lack of adherence. However, our goal is to enable students to plan and implement interventions that are as individualized as necessary. For our purpose, aiming to evaluate the implementation of MAP, quite the opposite could be argued: Few adaptations might be interpreted as having less integrity with the highly flexible and extensive approach that MAP represents. The same aspect holds true for the scale on MAP implementation that we initially used, as two items each asked students to self-rate their adherence to the Practitioner Guides.

Lastly, we used specific knowledge tests to assess changes of students’ information about MAP and the EBS system model, and the treatment of relevant mental disorders of children and adolescents. We found that our students already had a fairly high level of knowledge about the treatment of anxiety disorders before the seminar. Thus, the identification of changes could be limited by instrumental ceiling effects.

In summary, we conclude that specific assessments of relevant outcomes with pragmatic instruments should be pursued. The students’ limited prior experience should be taken into account. It would also be desirable to include external assessments, for example by the supervisor or independent evaluators. Incentives for study participation and especially completion need to be considered in view of the high drop-out rate.

Limitations

Interpretation and generalization of the results are limited by a small and homogeneous sample of predominantly female students and quite similar levels of professional experience. Due to the small sample size there is low statistical power, so relevant changes may not have reached statistical significance or could not be assessed. This is particularly evident in light of the low survey completion rate. It cannot be ruled out that the results are biased by the self-selection of those who continued to take part in the surveys. In light of this, future evaluations should set low demands while at the same time communicate the rationale for the assessments comprehensibly. Separate analyses of the self-rated competency progress for students with more or less professional experience or moderation analyses due to different attitudes towards EBP could be performed on larger samples in the future. Last but not least, it should be taken into account that since there is no comparison sample, the changes could have been caused by other course components, personal development, or external influences. Some of the measures we used were translated by our team and should be psychometrically investigated in German samples. In addition to internal consistency, factorial validity and measurement invariance should also be investigated in the given target group.

Conclusions

Our pilot study shows that MAP can be integrated into seminars of the BQT-II module and that knowledge and confidence gains among students and future psychotherapists can be achieved. The results help to improve further implementation of MAP into the master’s program and the German mental health care system. In upcoming semesters, the implementation of MAP will be continued and evaluated via BQT-II and BQT-III. In addition, a multicenter study is planned to investigate the effects of the implementation at different universities on the competence development of future psychotherapists and the treatment outcomes in child and adolescent outpatient clinics. Besides including assessments of patients as well as their caregivers to provide continuous feedback to our students, we plan to incorporate external assessments on the integrity of students’ implementation of MAP by evaluating their treatment plans and progress evaluations. In addition, we intend to distill relevant competencies for individualized psychotherapy and create and psychometrically investigate instruments for this purpose.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- AES

Adaptations to Evidence-Based Practices Scale

- BQT

Module on professional qualification (German: Berufsqualifizierende Tätigkeit)

- EBPAS-36D

Evidence Based Practice Attitudes Scale (German version)

- MAP

Managing and Adapting Practice

- MATCH

Modular Approach to Therapy for Children

- ODD

Oppositional defiant disorder(s)

- PCIS

Perceived Characteristics of Intervention Scale

- PTSD

Posttraumatic stress disorder(s)

- PWEBS

PracticeWise Evidence-Based Services database

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

Author contributions

The implementation of MAP in the master’s program was planned by H.C. and M.-L.C. with consultation of B.C. and T.B.. K.S., M.-L.C. and H.C. designed the study. K.S. created the proposal to the Ethics Review Board, created the surveys, collected and analyzed the data. K.S. drafted the manuscript. H.C., A.S.v.d.M., M.-L.C., B.C. and T.B. commented previous drafts and critically revised them. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The datasets without potentially identifying socio-demographic and occupational information analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

B.F.C. is a partner and co-owner of PracticeWise, LLC. T.B. is a senior consultant for PracticeWise, LLC, and serves on the Services and Products teams. T.B. provided instruction for seminar 1 as part of compensated work for PracticeWise and consultation regarding the implementation of MAP in the master’s program described in this manuscript. The remaining authors (K.S., A.S.v.d.M., M.-L.C., H.C.) declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-67407-w.

References

- 1.Pitchforth J, Fahy K, Ford T, Wolpert M, Viner RM, Hargreaves DS. Mental health and well-being trends among children and young people in the UK, 1995–2014: Analysis of repeated cross-sectional national health surveys. Psychol. Med. 2019;49(8):1275–1285. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2022;31(6):879–889. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Hawley KM, Jensen-Doss A. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: A multilevel meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2013;70(7):750–761. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisz JR, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM. Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Am. Psychol. 2006;61(7):671–689. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews G, Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Corry J, Lapsley H. Utilising survey data to inform public policy: Comparison of the cost-effectiveness of treatment of ten mental disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;184(6):526–533. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Burgess JF. Population-level cost-effectiveness of implementing evidence-based practices into routine care. Health Serv. Res. 2014;49(6):1832–1851. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoagwood KE, Olin SS, Horwitz S, McKay M, Cleek A, Gleacher A, et al. Scaling up evidence-based practices for children and families in New York State: Toward evidence-based policies on implementation for state mental health systems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014;43(2):145–157. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.869749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System For The 21st Century. National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonagy P, Cottrell D, Phillips J, Bevington D, Glaser D, Allison E. What Works For Whom? Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R, Jensen-Doss A, Hawley KM, Krumholz Marchette LS, Chu BC, Weersing VR, Fordwood SR. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: A multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am. Psychol. 2017;72(2):79–117. doi: 10.1037/a0040360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girlanda F, Fiedler I, Becker T, Barbui C, Koesters M. The evidence-practice gap in specialist mental healthcare: Systematic review and meta-analysis of guideline implementation studies. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2017;210(1):24–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.179093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee P, Lang JM, Vanderploeg JJ, Marshall T. Evidence-based treatments in community mental health settings: Use and congruence with children’s primary diagnosis and comorbidity. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2022;50(4):417–430. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00877-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chorpita BF, Bernstein A, Daleiden EL. Empirically guided coordination of multiple evidence-based treatments: An illustration of relevance mapping in children's mental health services. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79(4):470–480. doi: 10.1037/a0023982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the distillation and matching model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009;77(3):566–579. doi: 10.1037/a0014565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL. Coordinated strategic action: Aspiring to wisdom in mental health service systems. Clin. Psychol.: Sci. Pract. 2018;25:1–14. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chorpita BF, Daleiden E, Vera JD, Guan K. Creating a prepared mental health workforce: Comparative illustrations of implementation strategies. Evid.-Based Mental Health. 2021;24(1):5–10. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2020-300203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hogue A, Bobek M, Dauber S, Henderson CE, McLeod BD, Southam-Gerow MA. Core elements of family therapy for adolescent behavior problems: Empirical distillation of three manualized treatments. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019;48(1):29–41. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1555762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Looi JC, Pring W, Allison S, Bastiampillai T. Clinical update on psychiatric outcome measurement: What is the purpose, what is known and what should be done about it? Austral. Psychiatry. 2022;30(4):494–497. doi: 10.1177/10398562221092306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norcross JC, Wampold BE. What works for whom: Tailoring psychotherapy to the person. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011;67(2):127–132. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chorpita BF, et al. Long-term outcomes for the Child STEPs randomized effectiveness trial: A comparison of modular and standard treatment designs with usual care. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013;81(6):999–1009. doi: 10.1037/a0034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Park AL, Ward AM, Levy MC, Cromley T, Chiu AW, Letamendi AM, Tsai KH, Krull JL. Child STEPs in California: A cluster randomized effectiveness trial comparing modular treatment with community implemented treatment for youth with anxiety, depression, conduct problems, or traumatic stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017;85(1):13–25. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Collins KS. Managing and adapting practice: A system for applying evidence in clinical care with youth and families. Clin. Soc. Work J. 2014;42(2):134–142. doi: 10.1007/s10615-013-0460-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamura KH, Orimoto TE, Nakamura BJ, Chang B, Chorpita BF, Beidas RS. A history of child and adolescent treatment through a distillation lens: Looking back to move forward. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2020;47(1):70–85. doi: 10.1007/s11414-019-09659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higa-McMillan CK, Nakamura BJ, Daleiden EL, Edwall GE, Nygaard P, Chorpita BF. Fifteen years of MAP implementation in Minnesota: Tailoring training to evolving provider experience and expertise. J. Family Soc. Work. 2020;23(2):91–113. doi: 10.1080/10522158.2019.1694341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southam-Gerow MA, Daleiden EL, Chorpita BF, Bae C, Mitchell C, Faye M, Alba M. MAPping Los Angeles County: Taking an evidence-informed model of mental health care to scale. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014;43(2):190–200. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.833098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mennen FE, Cederbaum J, Chorpita BF, Becker K, Lopez O, Sela-Amit M. The large-scale implementation of evidence-informed practice into a specialized MSW curriculum. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2018;54:56–S64. doi: 10.1080/10437797.2018.1434440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez A, Lau AS, Wright B, Regan J, Brookman-Frazee L. Mixed-method analysis of program leader perspectives on the sustainment of multiple child evidence-based practices in a system-driven implementation. Implement. Sci. 2018;13(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0737-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chorpita BF, et al. Balancing effectiveness with responsiveness: Therapist satisfaction across different treatment designs in the Child STEPs randomized effectiveness trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015;83:709–718. doi: 10.1037/a0039301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reding ME, Guan K, Regan J, Palinkas LA, Lau AS, Chorpita BF. Implementation in a changing landscape: Provider experiences during rapid scaling of use of evidence-based treatments. Cogn. Behav. Pract. 2018;25(2):185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. MATCH-ADTC: Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety. Depression, Trauma, or Conduct Problems. PracticeWise; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett SD, et al. Clinical effectiveness of the psychological therapy Mental Health Intervention for Children with Epilepsy in addition to usual care compared with assessment-enhanced usual care alone: A multicentre, randomised controlled clinical trial in the UK. Lancet. 2024;403(10433):1254–1266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reding ME, Guan K, Tsai KH, Lau AS, Palinkas LA, Chorpita BF. Finding opportunities to enhance evidence-based treatment through provider feedback: A qualitative study. Evid.-Based Pract. Child Adolesc. Mental Health. 2016;1(2–3):144–158. doi: 10.1080/23794925.2016.1227948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook JM, Thompson R, Schnurr PP. Perceived characteristics of intervention scale: Development and psychometric properties. Assessment. 2015;22(6):704–714. doi: 10.1177/1073191114561254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rye M, Torres EM, Friborg O, Skre I, Aarons GA. The Evidence-based Practice Attitude Scale-36 (EBPAS-36): A brief and pragmatic measure of attitudes to evidence-based practice validated in US and Norwegian samples. Implement. Sci. 2017;12(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szota K, Thielemann JFB, Christiansen H, Rye M, Aarons GA, Barke A. Cross-cultural adaption and psychometric investigation of the German version of the Evidence Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS-36D) Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021;19(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00736-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau A, Barnett M, Stadnick N, Saifan D, Regan J, Wiltsey Stirman S, Roesch S, Brookman-Frazee L. Therapist report of adaptations to delivery of evidence-based practices within a system-driven reform of publicly funded children's mental health services. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017;85(7):664–675. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frank HE, Becker-Haimes EM, Kendall PC. Therapist training in evidence-based interventions for mental health: A systematic review of training approaches and outcomes. Clin. Psychol. 2020;27(3):e12330. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henrich D, Glombiewski JA, Scholten S. Systematic review of training in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Summarizing effects, costs and techniques. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023;101:102266. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stadnick NA, Lau AS, Barnett M, Regan J, Aarons GA, Brookman-Frazee L. Comparing agency leader and therapist perspectives on evidence-based practices: Associations with individual and organizational factors in a mental health system-driven implementation effort. Administr. Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv. Res. 2018;45(3):447–461. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0835-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finch J, Ford C, Grainger L, Meiser-Stedman R. A systematic review of the clinician related barriers and facilitators to the use of evidence-informed interventions for post traumatic stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;263:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly PJ, Deane FP, Lovett MJ. Using the theory of planned behavior to examine residential substance abuse workers intention to use evidence-based practices. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012;26(3):661–664. doi: 10.1037/a0027887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walfish S, McAlister B, O’Donnell P, Lambert MJ. An investigation of self-assessment bias in mental health providers. Psychol. Rep. 2012;110(2):639–644. doi: 10.2466/02.07.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Bishop MJ, Vermeersch DA, Gray GV, Finch AE. Comparison of empirically-derived and rationally-derived methods for identifying patients at risk for treatment failure. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2002;9(3):149–164. doi: 10.1002/cpp.333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spielmans GI, Masters KS, Lambert MJ. A comparison of rational versus empirical methods in the prediction of psychotherapy outcome. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. Int. J. Theory Pract. 2006;13(3):202–214. doi: 10.1002/cpp.491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lambert MJ, Whipple JL, Kleinstäuber M. Collecting and delivering progress feedback: A meta-analysis of routine outcome monitoring. Psychotherapy. 2018;55(4):520–537. doi: 10.1037/pst0000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reese RJ, Usher EL, Bowman DC, Norsworthy LA, Halstead JL, Rowlands SR, Chisholm RR. Using client feedback in psychotherapy training: An analysis of its influence on supervision and counselor self-efficacy. Train. Educ. Professional Psychol. 2009;3(3):157–168. doi: 10.1037/a0015673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011;45:626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borntrager CF, Chorpita BF, Higa-McMillan C, Weisz JR. Provider attitudes toward evidence-based practices: Are the concerns with the evidence or with the manuals? Psychiatr. Serv. 2009;60(5):677–681. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reding ME, Chorpita BF, Lau AS, Innes-Gomberg D. Providers' attitudes toward evidence-based practices: Is it just about providers, or do practices matter, too? Administr. Policy Mental Health. 2014;41(6):767–776. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0525-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets without potentially identifying socio-demographic and occupational information analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.