Abstract

Dostarlimab, a programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1)-blocking IgG4 humanized monoclonal antibody, gained accelerated approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2021, and received a full approval in February 2023. Dostarlimab was approved for treating adult patients with mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) recurrent or advanced endometrial cancer (EC) that progressed during or after prior treatment who have no other suitable treatment options. Herein, we review the structure-based mechanism of action of dostarlimab and the results of a clinical study (GARNET; NCT02715284) to comprehensively clarify the efficacy and toxicity of the drug. The efficacy and safety of dostarlimab as monotherapy was assessed in a non-randomized, multicenter, open-label, multi-cohort trial that included 209 patients with dMMR recurrent or advanced solid tumors after receiving systemic therapy. Patients received 500 mg of dostarlimab intravenously every three weeks until they were given four doses. Then, patients received 1000 mg dostarlimab intravenously every six weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The overall response rate, as determined by shrinkage in tumor size, was 41.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]; 34.9, 48.6), with 34.7 months as the median response duration. In conclusion, dostarlimab is an immunotherapy-based drug that has shown promising results in adult patients with recurrent or advanced dMMR EC. However, its efficacy in other cancer subtypes, the development of resistance to monotherapy, and efficacy and safety in combination with other immunotherapeutic drugs have not yet been studied.

Keywords: Dostarlimab, PD-1, Immunotherapy, Endometrial cancer, Check-point inhibitor

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Dostarlimab (TSR-042), is a programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1)-blocking monoclonal antibody.

-

•

Dostarlimab works by binding the PD-1 receptor, blocking PD-1 activity by preventing ligand (PD-L1 and PD-L2) binding.

-

•

Dostarlimab is indicated for treating adults with mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) recurrent or advanced endometrial cancer.

-

•

Dostarlimab was approved by the FDA in February of 2023.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) forms in the endometrial lining of the uterus and is characterized by a high rate of DNA mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR). Approximately 15,000 patients in the United States and 11,000 in the European Union are diagnosed with advanced or recurrent EC annually.1 Surgery alone, surgery along with adjuvant radiation, or surgery combined with chemotherapy (usually platinum-based doublet chemotherapy) can be used to treat early-stage EC.1 However, patients diagnosed with advanced or recurrent EC have a dismal prognosis. There are no approved, consensus-based guidelines for the care of those with illness that advance during or after therapy with a platinum-containing regimen.1 With response rates ranging from 7 to 14%, patients in this situation typically undergo salvage care with single-agent chemotherapy or hormone therapy, options with a median overall survival (OS) time of <1 year.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Furthermore, for patients with dMMR EC with progressive disease after platinum-containing therapy, no treatment has received regular FDA approval. Therefore, there is an unmet need for novel treatments of advanced and recurrent EC. One-third of EC tumors show evidence of dMMR.7 Tumors with deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) are often considered targets for immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly drugs that target the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or its ligand (PD-L1).

Dostarlimab, also known as TSR-042 is a humanized monoclonal antibody of the IgG4 isotype that binds to the programmed death (PD)-1 receptor of T cells and prevents interactions with its ligands, programmed death ligand (PD-L) 1 and PD-L2. An interaction between PD-L1 and PD-1 on the surface of a T cell diminishes PD-1 function and prevents the immune system from attacking tumor cells.8 The use of an inhibitor such as dostarlimab blocks interaction between PD-L1 and the PD-1 receptor. Recently, this type of inhibitor was suggested as an effective immunotherapy-based anticancer approach.8 Furthermore, a high objective response rate (ORR, 53%) of anti-PD-1 therapy across dMMR solid tumors has been observed.9 Genome-wide microsatellite instability (MSI) and the resultant tumor mutational load influence each patient's response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. The mechanistic basis for this preferential response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy is a disproportionate reliance on indel over missense mutations, driving positive clinical outcomes. Based on these observations, it has been proposed that anti-PD-1 therapy responders and non-responders in dMMR cancers can be predicted based on the intensity of a patient's MSI.9 This association was also observed in patients with advanced colorectal cancer in whom tumors with dMMRs were more responsive to anti-PD-1 than those without dMMR.10

Dostarlimab was recently authorized for the treatment of adult patients with recurrent or advanced dMMR EC who progressed during or after prior treatment with a platinum-containing regimen in a clinical setting. Accelerated approval for the drug was granted based on preclinical and clinical data, which demonstrated that dostarlimab inhibited the PD-1 receptor-ligand interaction, stimulated the antitumor immune response, and improved patient survival based on the GARNET clinical trial.6,11 Continued approval for use among these patients is contingent upon the verification and clarification of its clinical benefits in ongoing confirmatory trials. The anti-PD-1 antibody market is competitive, providing cancer patients with access to a range of new biological drugs with convenient dose schedules, tolerability profiles, disease-specific therapies, and costs. PD-1 inhibitors such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab have already been approved for several types of cancers including renal cell carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and bladder cancer; however, no PD-1 inhibitors were available for patients with recurrent or advanced EC with dMMR mutations until dostarlimab was approved. Furthermore, dostarlimab also has a significantly reduced level of antidrug antibody (ADA) emergence (2.5%), suggesting its potential for long-term efficacy as a treatment for patients with EC.6,11 Owing to the publication of these important findings, we aim to review current knowledge related to the structure-based mechanism of action of dostarlimab and clinical findings (GARNET; NCT02715284) on its efficacy and toxicity as a therapy.

Assessment of dostarlimab in combined therapy

The safety and efficacy of dostarlimab as a mono- or combination therapy are currently being clinically evaluated in patients with other types of cancers. In the search for ongoing or proposed studies using dostarlimab at clinicaltrials.gov (accessed July 29, 2023), 65 studies were identified as either ongoing, recruiting, or complete. Some ongoing studies assessing the dostarlimab as a part of combination therapy are discussed below.

An open-label, phase II study (NCT04837209, NADiR) assessed the safety and efficacy of the combined use of niraparib (a poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor), dostarlimab, and radiation therapy (RT) in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer.12 Niraparib prevents the repair of DNA damage, thereby aiding in killing metastatic triple-negative breast cancer cells.12 Dostarlimab has been proposed to act synergistically with niraparib by suppressing the activity of the PD-1 protein in triple-negative breast cancer cells, facilitating their identification and elimination by the immune system.12 Furthermore, combining RT with anticancer medications including dostarlimab and niraparib may further improve the ability of the immune system to systemically regulate or eradicate cancer cells.12 The primary outcome measure of this study was based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) criteria.12 The results of this trial will provide valuable insights into the efficacy and safety profile of dostarlimab in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents in patients with advanced or recurrent EC.12 Trial findings may expand treatment options and improve outcomes among this patient population.12

Dostarlimab and the anti-T cell immunoglobulin, mucin-containing protein-3 (TIM-3) antibody cobolimab (TSR-022) are currently being evaluated in a first-in-human trial (NCT02817633, AMBER) in patients with advanced solid tumors.13 The results of this study provide important insights into the safety and efficacy cobolimab combined with dostarlimab in the treatment of patients with specific tumor types.

A randomized phase II clinical trial (NCT04139902) aims to assess the safety and efficacy of either neoadjuvant therapy with dostarlimab or a PD-1/TIM-3 inhibitor (TSR-022) in combination with dostarlimab in patients with resectable, regionally advanced, or oligometastatic melanoma.14 Results will provide information regarding the safety and efficacy of the combined use of dostarlimab and cobolimab in patients with operable melanoma.14

The NCT03680508 phase II clinical trial is currently investigating the efficacy and safety of combining TIM-3- (cobolimab, TSR-022) and PD-1-binding antibodies (dostarlimab) in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)15 The expectation is that the combination of the two antibodies may stop the growth of tumor cells by allowing the immune system to attack cancerous cells, providing a treatment option for patients with locally advanced or metastatic liver cancer.15

It should be noted that the primary objective of the above studies was to assess the safety and efficacy of dostarlimab in combination with novel modalities in several malignant metastatic cancers, with the expectation that combination immunotherapies may improve patient ORRs, as determined based on immune-related response criteria (irRC), duration of response (DOR), time to progression (TTP), progression-free survival (PFS), OS. Final results of ongoing or proposed studies assessing the safety and efficacy of experimental combination therapies involving dostarlimab have not yet been made available.

Mechanism of action

Mechanism overview

Dostarlimab blocks PD-1 receptor recognition of PD-L1 and PD-L2 on tumor cells by binding to the PD-1 receptor with a high affinity [Figure 1].8 PD-1, a co-inhibitory receptor, is a crucial checkpoint protein that controls T cell tolerance. PD-1 ligands, which are extensively expressed in cancer cells, continually induce PD-1 expression, enabling cancer cells to avoid T cell-mediated immune responses.8 Therefore, tumor cells can be prevented from evading immune surveillance by blocking the binding of PD-1 to these ligands.8 Inhibition of PD-1 receptor binding activity was shown to slow tumor growth in mouse tumor models.8

Figure 1.

The mechanism of dostarlimab action. On the left, T cell recognition via PD-1 receptor binding to PD-L1 on the surface of tumor cells is shown. On the right, PD-1 receptor inhibition via binding to a PD-1 inhibitor is shown. This allows the tumor cell to avoid immune detection.8 PD-1: Programmed cell death receptor-1; PD-L1: Programmed cell death ligand 1; T cell: T lymphocyte cell.

Antibody engineering

Dostarlimab was genetically engineered from a mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) that was humanized by grafting heavy- and light-chain complementarity-determining onto germline variable region frameworks of their closest human orthologs, followed by affinity maturation through mammalian cell display and somatic hypermutation.16, 17, 18 Each heavy chain of the antibody contains a serine to proline substitution (S228P), which helps stabilize disulfide connections between heavy chains, preventing the development of half-antibodies.16 Although the heavy chain of dostarlimab interacts with PD-1, steric inhibition of PD-L1 binding is primarily mediated by its light chain. Dostarlimab alters the conformation of PD-1 BC, C'D, and FG loops to bind the receptor with high affinity.16 The amino acid residue R86 inside the C'D loop of PD-1 plays a crucial role in dostarlimab binding by occupying the concave surface of its heavy chain via many interactions.16 With a binding affinity (KD) of 300 pM, dostarlimab has a strong affinity for the human PD-1 receptor. Further, with association and dissociation rates of 5.7105/ms and 1.7104/s, respectively, dostarlimab exhibits rapid target association and delayed dissociation.16

The IgG4 isotype of dostarlimab was determined to be the most dependable and effective therapy approach.19 Dostarlimab prevents the depletion of tumor-reactive T cells because IgG4 isotypes only slightly increase Fc-mediated effector functions including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). The three approved anti-PD-1 antibodies pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and cemiplimab are all IgG4 isotypes. In contrast, atezolizumab, avelumab, and durvalumab, the three approved anti-PD-L1 antibodies, are all IgG1 isotypes.19 Chronic administration of IgG1 Fc with effectorless mutations could create additional immunogenic sites in a therapeutic scenario in which immunological augmentation is the goal.13 Notably, IgG2 antibodies are more difficult to produce than IgG1 or IgG4 antibodies. Overall, the inherent structural complexities and unique characteristics of IgG2 antibodies make their production more challenging compared to IgG1 or IgG4 antibodies.19

Preclinical studies

Dostarlimab was initially investigated in both in vitro and in vivo preclinical studies to elucidate its novel mechanism of action.19 In an in vitro study, dostarlimab was shown to bind human and cynomolgus monkey PD-1 molecules with similar affinities (KD = 1.8 and 1.5 nmol/L, respectively).13 Dostarlimab was also shown to compete with human PD-1 ligands when binding to PD-1, with IC50 values of 1.8 nmol/L for PD-L1 and 1.5 nmol/L for PD-L2.19 Preclinical findings for licensed PD-1 treatments including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and cemiplimab are comparable to this binding profile.20, 21, 22, 23 Further, cytokine release assays in human freshly isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells revealed that dostarlimab (up to 400 μg/well) did not induce significant production of interferon-gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10, indicating a low possibility of cytokine release syndrome when administered to patients.13 Following incubation with human dendritic cells and allogenic CD4+ T cells in a mixed lymphocyte reaction assay, dostarlimab induced human CD4+ T-cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner, with EC50 values ranging from 0.13 to 2 nmol/L.19

The antitumor efficacy of dostarlimab was assessed using humanized mouse models because dostarlimab does not bind to mouse PD-1. Dostarlimab displayed anticancer efficacy in this model system, as measured by the inhibition of tumor growth, which was mediated by an increase in immune cell infiltration.18 Dostarlimab was well tolerated by cynomolgus monkeys during single- and 4-week repeat-dose toxicity trials in which animals were given 10, 30, and 100 mg/kg/day dostarlimab.19 Taken together, the results of preclinical studies provide evidence of the anti-PD-1 receptor antagonistic properties of dostarlimab and suggest the usefulness of initiating clinical testing of the therapy in patients with cancer.

Clinical study supporting dostarlimab approval for treating mismatch repair deficient endometrial cancer

Study 4010-01-001 (GARNET trial, NCT02715284) was a multicenter, open-label, first-in-human, phase I, dose-escalation study with expansion cohorts designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics (PK), pharmacodynamics (PD), and clinical activity of dostarlimab when used as a monotherapy in patients with recurrent or advanced solid tumors who experienced disease progression during or after treatment with available anticancer therapies.1,23 The primary objective of this trial was to evaluate the antitumor activity of dostarlimab in patients with recurrent or advanced dMMR EC. The main outcome measure, ORR, was defined as the proportion of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response (PR) via blinded independent central review (BICR) based on RECIST v1.1 criteria. DOR was defined as the time from the first documented evidence of a complete or PR until the first documented sign of disease progression or death from any cause.1

Study design

The study (4010-01-001A) was initiated on March 7, 2016, and used a two-part, single-group, multi-cohort design.1 Assessment of the safety and effectiveness of dostarlimab monotherapy is ongoing.1 Adult patients with EC and dMMR were enrolled in the trial.

The study was conducted in two parts. Part 1 included a dose-escalation trial to assess weight-based dosages of dostarlimab monotherapy.1 Part 2 was an expansion of Part 1, with Part 2A assessing the safety of fixed doses of dostarlimab1 and Part 2B evaluating the anticancer potential and safety of dostarlimab among patients of four expansion cohorts designated based on tumor type and mutation status [cohort A1, dMMR EC; cohort A2, competent mismatch repair [MMR] EC; cohort E, NSCLC (Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer); and cohort F, Microsatellite-high (MSI-H)/dMMR non-endometrial solid tumors].1 One of the expansion cohorts (cohort A1) of patients with recurrent or advanced dMMR EC who developed advanced disease following treatment with a platinum-containing chemotherapy regimen was examined in the trial. Written informed consent was obtained from all included patients and the trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practices, the Declaration of Helsinki, and all applicable local laws.1

Study arms and interventions

Part 1: Participants receiving dostarlimab

Part 1 evaluated dostarlimab at ascending weight-based doses of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg. Dostarlimab was administered intravenously (IV) on days 1 and 15 of each cycle, with a cycle length of 28 days. Cohorts were enrolled sequentially and initially followed a 3 + 3 design.17

Part 2A: Participants receiving dostarlimab

In Part 2A, participants received a fixed dose of 500 mg Q3W or 1000 mg Q6W on day 1 of each cycle. The cycle duration for Q3W dosing was 21 days and that for Q6W dosing was 42 days. Cohorts included participants with advanced solid tumors. A modified 6 + 6 design following a 6 + 6 design will be used.17

Part 2B: Cohort A1, dMMR/MSI-H EC

Cohort A1 included participants with dMMR/MSI-H EC that progressed during or after platinum doublet therapy. These participants received 500 mg dostarlimab Q3W for the first four cycles, followed by 1000 mg Q6W for all subsequent cycles. Participants received no more than two lines of anticancer therapy for recurrent or advanced (Stage ≥ IIIB) disease.23

Part 2B: Cohort A2, MMR-proficient/microsatellite stable endometrial cancer (MSS EC)

Part 2 B: Cohort A2 included participants with MMR-proficient/MSS EC who had progressed on or after platinum doublet therapy. These participants received 500 mg dostarlimab Q3W for the first four cycles, followed by 1000 mg Q6W for all subsequent cycles. Participants received no more than 2 lines of anticancer therapy for recurrent or advanced (Stage ≥ IIIB) disease (25).

Part 2B: Cohort E, NSCLC

Cohort E included participants with NSCLC whose recurrent or advanced disease had progressed after prior use of at least one platinum-based systemic chemotherapy regimen. These participants received 500 mg dostarlimab Q3W for the first four cycles, followed by 1000 mg Q6W for all subsequent cycles.23

Part 2B: Cohort F, non-endometrial dMMR/MSI-H, and polymerase-epsilon mutations

Participants with recurrent or advanced dMMR/MSI-H solid tumors, excepting endometrial and gastrointestinal cancers, who received prior systemic therapy and had no alternative treatment options were included. These participants are scheduled to receive 500 mg dostarlimab Q3W for the first four cycles, followed by 1000 mg Q6W for all subsequent cycles of therapy.23

Part 2B: cohort G, platinum-resistant ovarian cancer without known breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA)

Participants with advanced, relapsed, high-grade serous, endometrioid, or clear cell ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer without known BRCA mutations who had platinum-resistant disease, and previously treated with bevacizumab were included. These participants received 500 mg dostarlimab Q3W for the first four cycles, followed by 1000 mg Q6W for all subsequent cycles.23

The mechanism of dostarlimab action makes it suitable for use in patients lacking BRCA mutations. Although dostarlimab does not explicitly target BRCA-related cancers, BRCA gene abnormalities are frequently associated with an increased risk of developing certain forms of cancers, including ovarian and breast.24 The decision to use dostarlimab in patients without BRCA mutations was based on the specific characteristics of the cancer and the overall treatment plan determined by the healthcare provider.24 Other factors such as the patient medical history, cancer stage, and previous treatment options were also considered.24

Study interventions

For patients enrolled in Part 1, dostarlimab (160 mg, 20 mg/mL or 500 mg, 50 mg/mL) was administered via a single, 30-min IV infusion on days 1 and 15 of each cycle.23 For additional patients enrolled to better characterize the PK/PD profile determined in Part 1, Cycle 1 dostarlimab administration took place on day 1, with the second dose administered on Cycle 2/Day 1, and Q2W thereafter.23 For those enrolled in Parts 2A and B, dostarlimab was administered on day 1 of each treatment cycle. The cycle durations for Q3W and Q6W dosing were 21 and 42 days, respectively.23

Study results

Treatment effectiveness

Assessment of dose escalation revealed that dostarlimab was well tolerated at doses of 30 and 100 mg/kg.23,25 Dostarlimab elicits a mild immune response in a small percentage of cancer patients after one or more cycles of treatment and has an ADA rate of 2.5%, a value comparable to those of other anti-PD-L1 medications.5 Furthermore, there is currently no evidence that the development of ADAs or ADAs that already exist have any effect on the safety or efficacy of the drug.5 Thus, dostarlimab was determined to be unlikely to induce immunogenic reactions.5

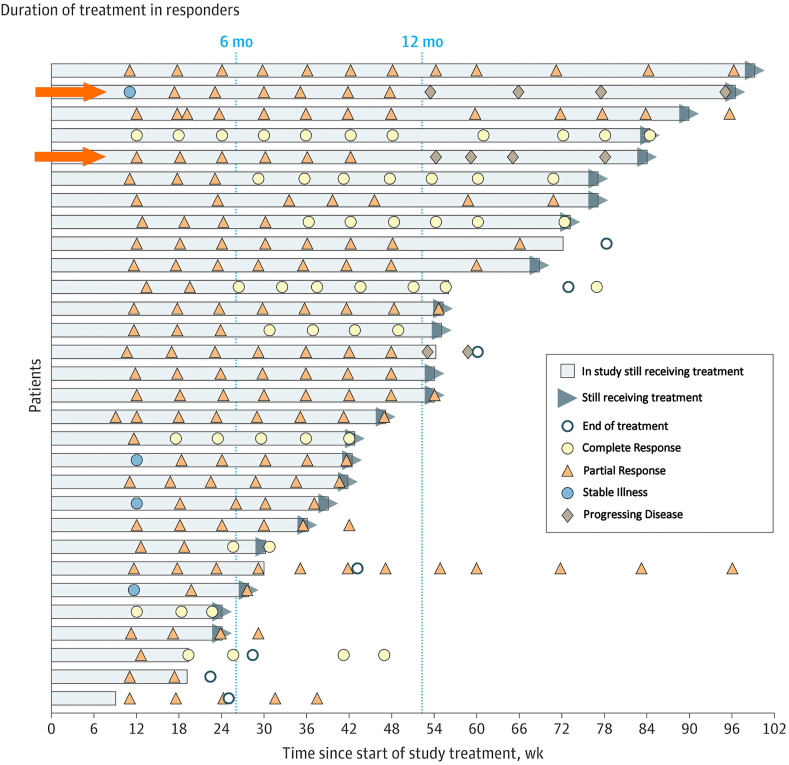

Assessment of the efficacy of treatment among cohort A1 demonstrated that patients with dMMR EC treated with dostarlimab had an ORR of 42.3% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 30.6%, 54.6%), with 12.7% achieving a complete response (CR) and 30% achieving a PR [Figure 2].1 The median DOR was not determined, but ranged from 2.6 to 22.4 months. Twenty-eight of 30 responders (93.3%) had a DOR ≥6 months.1 The ORR and DOR of dostarlimab for its recommended indications are therefore improved vs. those of available therapies, which include off-label use of single-agent cytotoxic chemotherapy or hormonal therapy with short-lived responses ranging from 7 to 14%.1 Dostarlimab successfully reduced tumor size in 42% of included individuals, based on results observed for the expansion cohort (Part 2B, Cohort A1).1

Figure 2.

Graph depicting the treatment duration among patients with an objective response to treatment. Patients were allowed to continue receiving treatment after progression if it was determined that they were benefiting from the therapy, as seen in lanes 2 and 5 (marked with orange arrows). In both cases shown, patients continued to receive dostarlimab despite having progressing disease based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) criteria but were considered responding under immune-related RECIST guidelines. Following the end of treatment, computed tomography scans were utilized to track disease progression.1 Continuous means that at the time of the data cutoff, the patient's treatment was ongoing. CR: Complete response; mo: Month; NE: Not evaluable; PR: Partial response; PD: Progressing disease; RECIST v1.1: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1; SD: Stable illness; wk: Week.

Treatment safety

The safety of dostarlimab was assessed in 104 patients with dMMR EC from Cohort A1 and also among 444 patients with various advanced solid tumors treated in Cohort A2 (MMR-proficient ECs), Cohort F (dMMR non-ECs), and Cohort E (NSCLCs).19 Safety assessments that were performed included symptom-directed physical examinations, vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status evaluations, and clinical laboratory assessments including a complete blood count (CBC) with differential (absolute lymphocyte count [ALC] and absolute neutrophil count [ANC]), coagulation profile, chemistry, thyroid panel, urinalysis, and pregnancy testing. Adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs (SAEs) were recorded for each patient after an informed consent form (ICF) was signed until 90 days after the end of treatment or until an alternate anticancer treatment was initiated, whichever occurred earlier; any pregnancies that occurred within 150 days post-treatment were reported.

Primary safety concerns associated with the anti-PD-1 class of therapeutics include immune-related AEs (irAEs) since the drugs modulate immune functioning. Another major safety concern includes infusion-related reactions. In subjects treated with dostarlimab as a standalone therapy, the most frequently reported irAEs (≥5% of subjects) were diarrhea (5.9%) and hypothyroidism (5.6%). IrAEs can be managed with dose interruption, discontinuation, and immunomodulatory agents including systemic steroids, immunosuppressants, and thyroid therapy, when required.25 Approximately 34% of patients who received dostarlimab experienced SAEs including sepsis, acute renal injury, urinary tract infection, stomach discomfort, and pyrexia [Table 1].26 Increased transaminase levels, sepsis, bronchitis, and pneumonitis were AEs that prompted the termination of drug administration (five patients).25

Table 1.

List of adverse reactions in patients with mismatch repair-deficient endometrial cancer receiving Dostarlimab in the GARNET study.

| Adverse reaction | Dostarlimab (N = 104)a |

|

|---|---|---|

| All grades (%) | Grade 3 or 4 (%) | |

| General and administration site | ||

| Fatigueb | 48 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||

| Nausea | 30 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 26 | 1.9 |

| Constipation | 20 | 0.9 |

| Vomiting | 18 | 0 |

| Blood and lymphatic system | ||

| Anemiac | 24 | 13 |

| Metabolism and nutrition | ||

| Decreased appetite | 14 | 0 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal | ||

| Cough | 14 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | ||

| Pruritus | 14 | 1 |

| Infections | ||

| Urinary tract infection | 13 | 1.9 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | ||

| Myalgia | 12 | 0 |

Toxicity was graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events Version 4.03.

Intent-to-treat (ITT) population (N = 104).

Includes fatigue and asthenia.

Includes anemia, hemoglobin decrease, iron deficiency, and iron deficiency.26

Despite a heavily pretreated patient population, the safety profile of dostarlimab was consistent with the known safety profile of other anti-PD-1 agents. Further, AEs observed are those commonly managed by physicians treating patients with cancer and cancer-related comorbidities.8 Overall, the incidence of treatment-emergent (treatment-induced or treatment-boosted) ADAs (3.7%; 2.0% neutralizing antibody [nAb]-positive) and overall ADA titers in patients were low.8 There is no evidence of clinically meaningful ADA formation regarding any safety or efficacy measures.8 Furthermore, in patients who were treated with dostarlimab at recommended therapeutic doses, six patients (1.4%) reported infusion-related treatment-emergent AE (TEAE), which were classified as infusion-related reactions (1.1%) or hypersensitivity (0.2%).8 There were no delayed infusion-related TEAEs and all TEAEs were reported on the day of dostarlimab administration.8 Taken together, dostarlimab demonstrated an acceptable safety profile with manageable toxicities based on data from 104 patients with dMMR EC and from a larger safety database of 444 patients with advanced solid tumors treated with dostarlimab monotherapy on Study 4010-01-001 (GARNET).8

Study Limitation

Although the above-discussed clinical trial (NCT02715284) is in phase 1, it has shown promising safety and efficacy profiles for dostarlimab in dMMR EC patients. Nonetheless, some potential caveats of this trial should be considered. The primary drawback of the GARNET trial was the lack of a comparator group, which prevented statistical comparisons with standard care. Additionally, the sample size was insufficient for reliable subgroup analyses at the time of the data cutoff. Patients were selected based on MMR status, which is currently the variable most consistently related to checkpoint inhibitor activity in EC. However, other indicators such as tumor mutational load and PD-L1 expression level were not investigated, which limits our ability to interpret trial findings. This clinical study may serve to further identify patients who will most benefit from treatment or, on the other hand, identify potential pathways of dostarlimab resistance in dMMR tumors. Despite these limitations, dostarlimab has been shown to have anticancer activity. Future data cutoff dates will offer further details regarding the advantages of the use of the drug among particular subgroups, the length of the response, and long-term safety. To better understand the efficacy and safety profile of dostarlimab, larger future trials are necessary. Currently, patients are being enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled RUBY trial (NCT03981796) that aims to assess the use of dostarlimab in combination with carboplatin-paclitaxel in primary advanced or recurrent EC.

Conclusions

Since the market for a novel anti-PD-1 antibody is already very competitive, a comparison between existing anti-PD-1 agents such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, and dostarlimab is necessary. Dostarlimab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the PD-1 receptor in immune cells and prevents the binding of PD-L1 to PD-L2. This helps unleash the immune response against cancer cells, whereas anti-PD-1 agents (such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab) block the PD-1 receptor by inhibiting the interaction between PD-1 and both PD-L1 and PD-L2 ligands, thereby showing an improved therapeutic effect. Dostarlimab is primarily approved for the treatment of advanced or recurrent EC with dMMR or MSI-H tumors, whereas pembrolizumab and nivolumab have broader indications and are approved for the treatment of several cancer types including melanoma, NSCLC, renal cell carcinoma, HNSCC, among others. Dostarlimab has shown promising results in clinical trials, demonstrating durable responses in patients with dMMR or MSI-H EC, including those with disease that has progressed with prior therapy. Dostarlimab has demonstrated significant clinical benefits as a primary therapy against various cancer types, leading to improved overall and progression-free survival rates in many patients. Moreover, dostarlimab use resulted in impressive ORR and DOR values compared with currently available therapies for patients with dMMR EC and had an acceptable safety profile.

Since it fulfilled an unmet medical need, Dostarlimab was awarded accelerated approval based on its favorable risk-benefit profile among its target patient population. However, the FDA recommends a post-marketing requirement for the submission of additional clinical trial results of ongoing study arms/trials to confirm the direct clinical benefit of the drug.27 Completion of this requirement has the potential to enable Dostarlimab to gain full FDA approval as monotherapy in adult patients with dMMR recurrent or advanced endometrial cancer that has progressed on or following a prior platinum-containing regimen in any setting and are not candidates for curative surgery or radiation. Therefore, studying dostarlimab will likely expand treatment options, foster market competition, and improve our understanding of its clinical effectiveness, disease-specific drug indications, usefulness in combination therapies, and safety and tolerability. Further, additional knowledge will foster market competition. These efforts have improved patient outcomes and advanced cancer immunotherapy.

Funding

None.

Authors contribution

Siddhant Shukla and Zhe-Sheng Chen: conceptualization; Siddhant Shukla, Harsh Patel, Shuzhen Chen, and Rainie Sun: searching literature, and writing the original draft; Zhe-Sheng Chen and Liuya Wei: reviewing and editing the text; Zhe-Sheng Chen and Liuya Wei: supervision.

Ethics statement

None.

Data availability statement

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The first author, Siddhant Shukla, would like to thank the GA at the Venture Clinical Lab under Dr. Marc Gilespie and the Institute for Biotechnology.

Managing Editor: Peng Lyu

Contributor Information

Liuya Wei, Email: xiaoyawfmc@163.com.

Zhe-Sheng Chen, Email: chenz@stjohns.edu.

References

- 1.Oaknin A., Tinker A.V., Gilbert L., et al. Clinical activity and safety of the anti-programmed death 1 monoclonal antibody dostarlimab for patients with recurrent or advanced mismatch repair-deficient endometrial cancer: a nonrandomized phase 1 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1766–1772. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boll D., Karim-Kos H.E., Verhoeven R.H., et al. Increased incidence and improved survival in endometrioid endometrial cancer diagnosed since 1989 in The Netherlands: a population based study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;166:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muggia F.M., Blessing J.A., Sorosky J., Reid G.C. Phase II trial of the pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in previously treated metastatic endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2360–2364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dizon D.S., Blessing J.A., McMeekin D.S., Sharma S.K., Disilvestro P., Alvarez R.D. Phase II trial of ixabepilone as second-line treatment in advanced endometrial cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group trial 129-P. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3104–3108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fracasso P.M., Blessing J.A., Molpus K.L., Adler L.M., Sorosky J.I., Rose P.G. Phase II study of oxaliplatin as second-line chemotherapy in endometrial carcinoma: a gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia A.A., Blessing J.A., Nolte S., Mannel R.S. A phase II evaluation of weekly docetaxel in the treatment of recurrent or persistent endometrial carcinoma: a study by the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le D.T., Durham J.N., Smith K.N., et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.JEMPERLI . GlaxoSmithKline; 2021. Prescribing information.https://gskpro.com/content/dam/global/hcpportal/en_US/Prescribing_Information/Jemperli/pdf/JEMPERLI-PI-MG.PDF Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandal R., Samstein R.M., Lee K.W., et al. Genetic diversity of tumors with mismatch repair deficiency influences anti–PD-1 immunotherapy response. Science. 2019;364:485–491. doi: 10.1126/science.aau0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira A.F., Bretes L., Furtado I. Review of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic dMMR/MSI-H colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:396. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.GSK receives FDA accelerated approval for JEMPERLI (dostarlimab-gxly) for adult patients with mismatch repair-deficient (dMMR) recurrent or advanced solid tumours. GSK Press Release; London: 2021. https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-receives-fda-accelerated-approval-for-jemperli-dostarlimab-gxly-for-adult-patients-with-mismatch-repair-deficient-dmmr-recurrent-or-advanced-solid-tumours/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott E., Isakoff S.J., Taghian A.G., et al. Abstract OT2-09-01: TBCRC-055: a Phase II Study of nirAparib, dostarlimab, and radiotherapy in metastatic, PD-L1 negative or immunotherapy-refractory triple-negative breast cancer (NADiR)- NCT04837209. Cancer Res. 2023;83:OT2–9. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS22-OT2-09-01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A study of TSR-022 in participants with advanced solid tumors (AMBER) National Library of Medicine; Bethesda: NIH: 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02817633?term=NCT02817633&rank=1 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randomized phase II neoadjuvant study of PD-1 inhibitor dostarlimab (TSR-042) vs. combination of Tim-3 inhibitor cobolimab (TSR-022) and PD-1 inhibitor dostarlimab (TSR-042) in resectable stage III or oligometastatic stage IV melanoma (Neo-MEL-T) National Library of Medicine; Bethesda: NIH: 2023. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04139902?term=NCT04139902&rank=1 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phase II study of TSR-022 (cobolimab) in combination with TSR-042 (dostarlimab) for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. NIH, National Library of Medicine; Bethesda: 2022. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03680508?term=NCT03680508&intr=NCT03680508&rank=1 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park U.B., Jeong T.J., Gu N., Lee H.T., Heo Y.S. Molecular basis of PD-1 blockade by dostarlimab, the FDA-approved antibody for cancer immunotherapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2022;599:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowers P.M., Horlick R.A., Neben T.Y., et al. Coupling mammalian cell surface display with somatic hypermutation for the discovery and maturation of human antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20455–20460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114010108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horlick R.A., Macomber J.L., Bowers P.M., et al. Simultaneous surface display and secretion of proteins from mammalian cells facilitate efficient in vitro selection and maturation of antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:19861–19869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.452482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S., Ghosh S., Sharma G., et al. Preclinical characterization of dostarlimab, a therapeutic anti-PD-1 antibody with potent activity to enhance immune function in in vitro cellular assays and in vivo animal models. mAbs. 2021;13:1954136. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2021.1954136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fessas P., Lee H., Ikemizu S., Janowitz T. A molecular and preclinical comparison of the PD-1-targeted T-cell checkpoint inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Semin Oncol. 2017;44:136–140. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan S., Zhang H., Chai Y., et al. An unexpected N-terminal loop in PD-1 dominates binding by nivolumab. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14369. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longoria T.C., Tewari K.S. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of pembrolizumab in the treatment of melanoma. Expet Opin Drug Metabol Toxicol. 2016;12:1247–1253. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2016.1216976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Participants with advanced solid tumors (GARNET) U.S. National Library of Medicine; Bethesda: 2016. Study of TSR-042, an anti-programmed cell death-1 receptor (PD-1) monoclonal antibody.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02715284 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alkholifi F.K., Alsaffar R.M. Dostarlimab an inhibitor of PD-1/PD-L1: a new Paradigm for the treatment of cancer. Medicina. 2022;58:1572. doi: 10.3390/medicina58111572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa B., Vale N. Dostarlimab: a review. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1031. doi: 10.3390/biom12081031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safety profile of JEMPERLI. https://www.jemperlihcp.com/safety/garnet-trial

- 27.FDA D.I.S.C.O Burst Edition: FDA approval of Jemperli (dostarlimab-gxly) for dMMR endometrial cancer. Silver Spring: FDA. 2023 https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-disco-burst-edition-fda-approval-jemperli-dostarlimab-gxly-dmmr-endometrial-cancer Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.