Abstract

Polysaccharides (PSAs) are carbohydrate-based macromolecules widely used in the biomedical field, either in their pure form or in blends/nanocomposites with other materials. The relationship between structure, properties, and functions has inspired scientists to design multifunctional PSAs for various biomedical applications by incorporating unique molecular structures and targeted bulk properties. Multiple strategies, such as conjugation, grafting, cross-linking, and functionalization, have been explored to control their mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, hydrophilicity, degradability, rheological features, and stimuli-responsiveness. For instance, custom-made PSAs are known for their worldwide biomedical applications in tissue engineering, drug/gene delivery, and regenerative medicine. Furthermore, the remarkable advancements in supramolecular engineering and chemistry have paved the way for mission-oriented biomaterial synthesis and the fabrication of customized biomaterials. These materials can synergistically combine the benefits of biology and chemistry to tackle important biomedical questions. Herein, we categorize and summarize PSAs based on their synthesis methods, and explore the main strategies used to customize their chemical structures. We then highlight various properties of PSAs using practical examples. Lastly, we thoroughly describe the biomedical applications of tailor-made PSAs, along with their current existing challenges and potential future directions.

Keywords: tailor-made, polysaccharides, biomedical applications, tissue engineering, drug delivery

1. Introduction

Polynucleotides, lipids, proteins, and polysaccharides (PSAs) represent distinct classes of covalently synthesized multifunctional biomacromolecules that are essential for life in all animals, including humans. Among these, PSAs stand out as the most abundant natural biopolymers. They are used by microorganisms, algae, plants, and animals for energy storage and/or structural support.1 PSAs are typically synthesized through a natural carbon-capture process in various photosynthetic organisms, such as plants. In this process, which harnesses the energy of sunlight, inorganic carbon present in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide is converted into organic carbons, including high-energy storage molecules such as lipids and PSAs.2 In contrast to proteins and nucleic acids, the cellular machinery does not use a template to make PSAs. Therefore, PSA synthesis naturally forms a variety of microstructures whose composition depends on the type of cells or microorganisms performing the synthesis.

PSAs are ubiquitous components of cells. A dense and complex coating of oligosaccharides (OSAs) or PSAs, also called glycans, has been observed to cover the plasma membrane of nearly all cell types in nature. The OSAs or PSAs may be conjugated with proteins or lipids, a process known as glycosylation, to aid protein folding and to make multifunctional biomacromolecules that can mediate or regulate various functions in diverse cellular interactions.3 In addition, PSAs play prominent roles in many biological processes, such as cell adhesion and recognition, differentiation, signaling, and microbial attachment.4 Multivalent protein–carbohydrate interactions are vital in such biological processes.5 Due to the bioactivity of PSAs, many PSA-containing plants, fungi, and algae have been traditionally used as medications, such as in traditional Chinese medicine.6 Since the discovery that they possess bioactivities, PSAs have also gained many clinical applications. One notable example occurred in 1988 when PSAs were observed to be immunomodulating agents with numerous activities and antiviral properties.7

PSAs and their derivatives have been utilized in many applications, such as food and therapeutics.8 For example, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), a cellulose ether, is a widely used water-soluble food additive, and alginate/alginate derivatives are commonly used in wound dressing applications and hemostasis agent production.9,10 On the other hand, PSA-based vaccines, which are based on capsular PSAs (CPSAs) and lipopolysaccharides, are an essential class of vaccines utilized to prevent various infections.11 Nevertheless, due to the structural diversity of PSAs (in terms of structural monomers, glycosidic linkages, and pendant functional groups), their chemical complexity, and hurdles associated with isolating them from various natural resources, understanding their structure–function relationships remains a significant challenge. Consequently, designing and fabricating tailor-made PSAs has also proven to be quite challenging.

Both chemical structure (e.g., molecular weight, glycosidic linkages, branching, and functional groups) and molecular conformation affect the physiochemical characteristics and bioactivity of PSAs.12,13 For example, low molecular weight and the presence of anionic and hydrophilic groups are factors that enhance the water solubility of PSAs. The water solubility of carboxymethyl chitosan (CMCS), which bears carboxymethyl functional groups, is significantly higher at nearly neutral pH than unmodified chitosan (CS). As a Lewis base, CS can only dissolve in a mildly acidic environment (pH < 6.5) because of the creation of soluble −NH3+ moieties on glycosamine units. Furthermore, acetylation that affects the conformation of a PSA may significantly increase its solubility by exposing its hydroxyl groups to water molecules. Chemical, physical, and biological modifications of PSAs can govern the physiochemical and bioactivity of those PSAs. Bioactivity refers to the capacity of a chemical to interact with biological systems, leading to a biological effect or response. This can manifest as antibacterial effects, immunogenicity, inflammation, or antioxidant properties. Grafting or conjugation with other (bio)(macro)molecules, oligomers, and polymers can endow PSAs with increased complexity, conformational versatility, and enhanced biological activities. Furthermore, the rheological and gelling properties of PSA aqueous solutions are determined by the chemical structure and conformation of the polymer chains. In addition, physical or chemical cross-linking features (e.g., cross-linker type and cross-linking density) of PSAs significantly affect the mechanical properties of PSA-based hydrogels.14−18 Utilization of PSA-based hydrogels for tissue engineering, drug delivery, and three-dimensional (3D) or four-dimensional (4D) bioprinting is highly dependent on their physicochemical, mechanical, rheological, and biological properties.19−21 Property alternation/reversal in PSAs originates from chemical and conformational features that correspond to unique electronic structures. Thus, tailoring PSAs is critical for adjusting their properties to meet specific applications in the biomedical arena.22−24

Tailor-made polymers have been at the center of attention over the past three decades. There has also been a continued push for tailor-made macromolecules, long-chain molecules with predefined chemical architectures, for the purpose of obtaining polymeric materials with anticipated properties.25−27 The concept of tailor-made macromolecules was inspired by the idea of using polymerization reactions or design systems to seek outstanding properties of macromolecules via an inverse design strategy, i.e., beginning with a desired property and then achieving this property through rounds of design and experimentation.28−31 Tailoring provides a vast playground for materials scientists to design and manufacture diverse polymers with unique features based on different (co)monomers, oligomers, side chains, and cross-linking states. On the other hand, this strategy requires the ability to pattern macromolecules with controlled molecular weights and architectures among the multitude of potential macromolecular configurations.32 Copolymerization of different types of monomers has traditionally been considered an essential strategy for making novel polymers with unique properties.33−35 For example, poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(propylene glycol)-b-poly(ethylene glycol), known as poloxamer or Pluronic, is a nonionic triblock (ABA) copolymer. Two hydrophilic terminal oligomer segments, i.e., poly(ethylene oxide), and one hydrophobic central oligomer segment, i.e., poly(propylene oxide), give this polymer its amphiphilic nature and thermosensitive properties.36,37 This enables poloxamer to be utilized in micelle-based intelligent drug delivery systems (DDSs). Additionally, it is possible to make injectable hydrogels based on poloxamer for tissue engineering applications.38,39 As another example, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) is a synthetic biodegradable random copolymer that has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has a broad range of applications in drug delivery and cancer treatment.40−44 Hydrolysis of ester linkages results in PLGA degradation both in vitro and in vivo. The degradation rate of this copolymer can be tailored primarily by varying the ratio of lactide to glycolide (i.e., the comonomer ratio, L/G).45,46 Tailor-made hydrogels with desired properties can be created by selecting appropriate (co)monomers and adjusting their ratio, as well as the type of cross-linker(s), density, and feeding policy during polymerization.47−49

Several review articles have explored the application of PSA-based adhesives or their derivatives in various biomedical applications. However, many of these reviews focus on individual PSAs or limited applications, providing readers with a narrower perspective. For instance, Kim et al. concentrated on hyaluronic acid (HA) and its derivatives for specific biomedical applications but did not delve into the chemical tailoring procedures.50 Similarly, Liu et al. examined various strategies for the chemical modification of PSAs but did not explore their biomedical applications in depth.51

PSAs, as abundant natural biopolymers, have been widely utilized for biomedical applications such as cell therapy, gene or drug delivery, different facets of tissue engineering, wound healing, and bioprinting technology.52−54 However, their properties must be modified to expand their applications in future medicine. The pressing need for modification comes from existing weaknesses in specific mechanical or biological properties and a lack of unique functionalities. For instance, naturally thermoresponsive PSAs (like agarose and carrageenan) can be converted from solution to gel state upon cooling, i.e., a sol–gel transition that is undesirable for some biomedical applications.55 For instance, the sol phase is preferred for cell encapsulation, but this requires raising the temperature in thermoresponsive PSAs, which can damage living cells.56 Accordingly, making tailored thermoresponsive PSAs with lower critical solution temperatures can preserve cell viability and result in enhanced biomedical applications.57 In addition, the increased use of PSA-based materials in biomedical applications has encouraged scientists to look for state-of-the-art methods or facilities to improve the extraction processes. One practical improvement is an enzymatic modification that leads to the generation of smaller and better-defined molecules.58 Among the different modifications, the easiest and most common is a chemical modification that explicitly focuses on the oxidation of the PSA backbone.59 This introduction has presented a general overview of the modification strategies for PSAs and touched on the chemical processes, ranging from the synthesis of PSAs to the modification of their microstructure. The following section discusses the properties and applications of modified PSAs in more detail.

2. Chemical modifications of PSAs

As shown in Table 1, various PSAs can be found in abundance in natural resources. Most studies rely on the isolation of natural PSAs from multiple species, such as plants and microorganisms. However, some bacteria are purposely cultured to make exopolysaccharides (EPSAs). Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), or mucopolysaccharides, are long, unbranched PSAs with high water absorption capabilities. These alternating copolymers are ubiquitous in animal tissues and possess vital features, including water retention, promotion of cell attachment and proliferation, superior ability to direct cell differentiation, and binding to cytokines and growth factors. GAGs such as heparin, heparan sulfate, keratan sulfate (KS), dermatan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, and HA play essential roles in the biological functions of animal tissues.60,61 On the other hand, the total synthesis of OSAs/PSAs has been extensively investigated over the last three decades to prepare well-defined oligomers or polymers, particularly for fundamental studies such as structure–property-function relationships.62,63 While these studies have led to outstanding achievements such as automated glycan assembly (AGA), the corresponding methods may require further improvement and will not be covered here.

Table 1. Classification of Naturally Derived Polysaccharides (PSAs) Is Based on Their Origins, Chemical Structures, Functional Groups, Properties, and Biomedical Applications64−90.

Chemical, physical, and biological modification strategies are robust methods for improving the physicochemical properties and biological activities of PSAs. Chemical modification of naturally derived PSAs is a versatile and robust strategy for creating tailor-made PSAs. Partial substitution of functional groups of PSAs with other functionalities, small molecules, oligomers, or polymers provides a leading strategy to tailor PSAs for specific applications. In addition, changes in the PSA backbone (e.g., oxidation of some of the pyranose rings, backbone truncation) can result in new polymeric structures. However, designing new tailor-made PSAs with special features requires basic knowledge of how the various chemical modifications affect the physicochemical properties and bioactivities of PSAs. For example, a PSA-based, targeted DDS for delivery of hydrophobic chemotherapeutics requires the design or selection of an amphiphilic PSA with pH-responsiveness so that it releases its payload in the slightly acidic tumor microenvironment (TME). Furthermore, PSAs possessing inherent antitumor properties can be especially useful in designing DDSs for cancer treatment since they can act as dual-action anticancer nanomedicines.91 The designer can select a natural PSA with inherent antitumor activity and enhance its anticancer activity via chemical modification strategies such as sulfation. Bioactive PSAs can serve as therapeutics, and DDSs can improve their curative efficacy.92 Enhancing the solubility of PSAs, optimizing gelling/melting temperature, endowing responsiveness against various stimuli (e.g., pH, redox moieties, light, and temperature), and adjusting degradation rate would significantly enhance in vivo applications of PSAs.93 For example, xanthan gum (XG) is a microbial EPSA with various biomedical uses. However, it has several limitations, such as poor water solubility and inadequate mechanical stability. Accordingly, several strategies for chemical modification and cross-linking have been used to tailor the properties of XG.94

The molecular weight of PSAs can be reduced by chain scission via chemical, physical, or biological methods. On the other hand, the ring opening of sugar units via partial oxidation results in the formation of reactive functional groups (e.g., aldehyde), facilitating further modifications. Moreover, sugar units in PSAs are rich in various functionalities, such as primary alcohol, carboxylic acid, and amine. Based on the chemical functional groups, PSAs can be classified into three categories, as shown in Table 1. These functional groups can be involved in the PSAs’ modifications.95 These strategies apply to both molecular and surface modifications (usually in heterogeneous reactions).

2.1. Esterification

Esterification is one of the most important processes used in the chemical functionalization of PSAs. Esterification is a process that can improve the stability and water solubility of PSAs, while also allowing for customization of their physicochemical properties such as viscosity and gelation time.96,97 For example, the esterification of κ-carrageenan with various fatty acids has been shown to affect properties such as gelling behavior, swelling, viscosity, thermal stability, and mechanical properties of the resulting PSA.98 Consequently, harnessing esterification for tailoring the properties of PSAs can lead to the development of hydrogels with desirable gelling properties and enhanced mechanical strength, making them highly attractive for applications in tissue engineering.

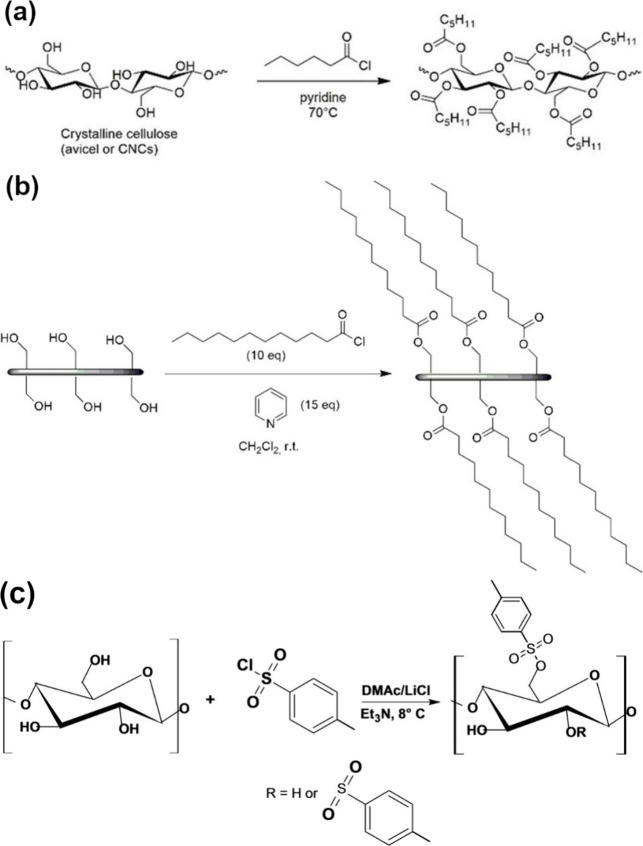

Cellulose esters (e.g., nitrocellulose and cellulose acetate) have many critical industrial applications.99 These applications include, but are not limited to, sensors, reinforcement agents, biomaterials, and interfacial materials. The specific application field depends on the type of ester moieties introduced.100 Esterification of cellulose nanomaterials results in the formation of functional nanomaterials that can be classified into inorganic (e.g., cellulose nitrate and cellulose phosphate) and organic (e.g., cellulose acetate) cellulose esters.101 Cellulose acetate is typically produced using Fischer esterification, which involves refluxing acetic acid and acetic anhydride with cellulose in the presence of a strong acid catalyst, such as sulfuric acid.102 Activated derivatives of carboxylic acids (e.g., acid halides or anhydrides) can react with alcohols in basic pH. In addition to these activated derivatives, vinyl carboxylates can also act as acyl donors.103 Note that selecting proper solvents is critical for the homogeneous functionalization of PSAs. Surface modification of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) with lauroyl chloride also resulted in lauroyl ester groups on the hydrophobically modified nanopaper, as schematically presented in Figure 1.104 The esterification reaction was conducted in dichloromethane (DCM)/pyridine using lauroyl chloride as the acyl donor.105,106

Figure 1.

Enhanced hydrophobicity of cellulose. (a) Esterification of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) using an acid halide (i.e., hexanoyl chloride) in the presence of pyridine, resulting in hexanoyl derivatives of CNC with suppressed hydrogen bonding, soluble in (non)polar solvents. (b) Making hydrophobic, freestanding cellulose nanopaper through surface treatment using lauroyl chloride as acyl donor, resulting in ester bond formation. Adapted with permission from ref (104). Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry. (c) Cellulose tosylation using p-tosyl chloride in a DMAc/LiCl system containing trimethylamine.107 Reproduced with permission from ref (107). Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH.

Sulfonate esterification of PSAs can be performed using toluenesulfonates and methanesulfonates. For instance, cellulose was dissolved in N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc)/LiCl (8%), followed by a reaction with tosyl chloride and mesyl chloride under homogeneous conditions to yield tosylated/mesylated cellulose.108,109 As schematically illustrated in Figure 1, tosylation can occur in cellulose in a DMAc/LiCl system with trimethylamine (Et3N) as the basic catalyst.107

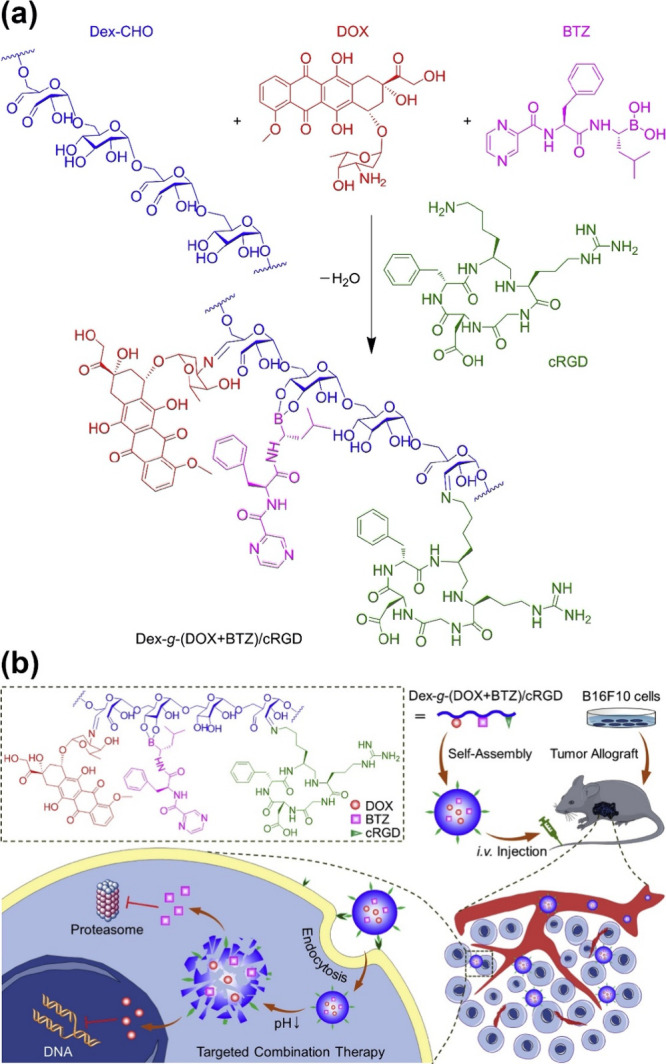

Ester functional groups can be created through the chemical reaction between carboxylic acid groups and hydroxyl groups or epoxides. PSAs like alginate, which contain carboxyl residues, can react with the oxirane functionalities of other molecules to create ester linkages. For example, the esterification of pristine hydrophilic sodium alginate with propylene oxide results in surface-active propylene glycol alginate (PGA), an ester of alginic acid.110 Moreover, the esterification of alginate using poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) results in the creation of ester linkages (i.e., cross-linking) and improved physicochemical and mechanical properties of the obtained polymer network.111 Hydroxyl groups on sugar units can react with monochloroacetic acid (MCA) to create carboxymethyl derivatives of PSAs, such as CMCS. Carboxymethyl groups can further react with alcohols to produce methyl ester derivatives that are more reactive compared to carboxylic acid groups. For example, amino-dealkoxylation of methyl ester–functionalized CS and β-glucan results in the amidation of these PSAs.112 Oxidized dextran (OD) bearing aldehyde groups was conjugated with the cyclic peptide cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp-d-Phe-Lys) (c(RGDfK)) and the anticancer drug doxorubicin (DOX) via Schiff base reaction.113 Additionally, bortezomib (BTZ), another anticancer drug, was conjugated to dextran (Dex) via boronic ester linkages, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Targeting cancer cells using chemically modified Dex-g-(DOX+BTZ)/cRGD. (a) The Schiff base reaction between aldehyde functional groups on oxidized dextran (Dex-CHO) and primary amines on the cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic acid peptide (cRGD) or doxorubicin (DOX). Boronic esterification of adjacent OH on pyranose ring and boronic acid on bortezomib (BTZ). (b) Self-assembly of modified dextran into micelles in an aqueous environment; intravenous injections of micelles followed by tumor-site accumulation due to EPR effect; micelle uptake by cancerous cells and disassembly of nanomedicine in the acidic endosome environment followed by drug release in the cytosol.113 Reproduced with permission from ref (113). Copyright 2020, Elsevier.

The obtained PSA, containing two anticancer drugs and a cyclic peptide, self-assembles into 80 nm micelles in aqueous media. This nanomedicine is a synergistic cancer therapy that accumulates in tumor tissue via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Integrin αvβ3, which plays an essential role in angiogenesis and tumor progression, can be targeted via the cRGD sequence of cRGDfK in the nanomedicine formulation. The nanomedicine can target cancer cells via αvβ3–cRGD interplay before entering cancer cells through endocytosis. The acidic microenvironment within the endosome triggers the release of the anticancer drugs into the cytosol, as depicted in Figure 2.

Another research team reported that the esterification of alginic acid can be considered a standard chemical route for improving the functionality of tableting excipients. They claimed that higher levels of methylation brought greater tensile strength and compressibility, in addition to the slower disintegration resulting from the introduced hydrophobicity.114 Interestingly, it was found that the immunomodulatory effect of pectin is a function of methyl-esterification and molecular mass. For instance, 56% methyl-esterification of pectin confers an immunomodulatory effect on this PSA. It can increase macrophage cell activity by 39%, phagocytic activation by 30% (after 2 days), and peritoneal macrophage activity by 490% after 1 day.115

2.2. Etherification

Etherification is an essential class of chemical functionalization of PSAs. Cellulose ethers (e.g., CMC, methylcellulose (MC), hydroxyethyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC), ethylcellulose (EC), and hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC)) are produced at industrial scale for various applications, such as food, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and personal care, adhesives, paints, and coatings.116 Etherification, another chemical modification process, can enhance the solubility, stability, and chemical versatility of PSAs, while also improving their film-forming ability and reducing immunogenicity.117 Furthermore, etherification can introduce additional functionalities such as stimuli-responsiveness. For instance, by etherifying chitosan, it is possible to produce thermosensitive hydrogels based on hydroxybutyl chitosan, which can serve as an intelligent drug delivery platform.118

The reaction between the alcoholic hydroxide group on PSAs and an alkylating agent (e.g., alkyl halides) in the presence of a strong base results in ether linkage formation. In such reactions, the saccharide oxygen acts as a nucleophile. For example, etherification of pullulans using two alkyl halides (i.e., 1-bromopropane and 1-bromobutane) was carried out in the presence of sodium hydroxide (NaOH).119 The most crucial ether derivatives of PSAs can be classified as alkyl, benzyl, carboxymethyl, and hydroxyethyl ethers. MC and its salts serve as alkylating agents to create carboxymethyl ethers in the presence of NaOH.120,121 Ring-opening reactions of epoxides (e.g., in ethylene oxide and propylene oxide) are vital to creating PSA ethers such as hydroxypropyl starch and hydroxyethyl starch (HES), which is used as a blood plasma volume expander.122,123

2.3. Amidation

Amide linkage formation is possible between amine-bearing PSAs, such as CS or synthetic aminated PSAs, and carboxylic acid groups. Amine nucleophiles react with electrophiles to produce various functionalities such as amides, imines, and quaternary ammonium salts. The ammonium salts usually come from the acid-based reaction unless the temperature is elevated. The amine group of CS can be activated using carbodiimides (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl) carbodiimide (ECD)) to react with carboxylic acid-bearing molecules such as fatty acids to make amphiphilic PSAs. Carboxylic acids can serve as electrophiles for amine nucleophiles.

Amidation is a process that significantly increases the solubility and stability of PSAs, while also enhancing or inducing bioactivity within them.124 For example, incorporating amide bonds into chitosan has been shown to impart antibacterial and antioxidant properties.125 Additionally, since amide bonds can participate in hydrogen bonding, PSAs modified through amidation can form hydrogels with superior mechanical strength.

However, carboxylic acid functional groups should be activated before amidation. Carbodiimides are commonly employed as bifunctional coupling reagents to activate and link these functional groups. Among carbodiimide chemistry’s coupling agents, water-soluble EDC and organo-soluble N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) are the most widely used.

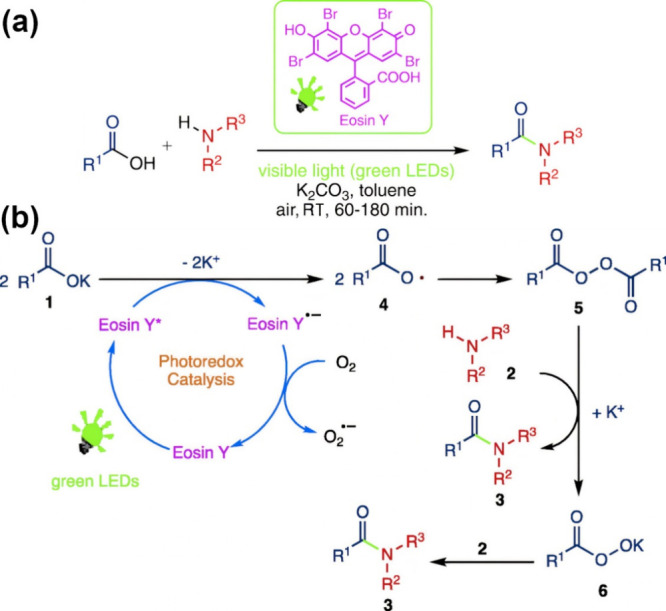

The amidation reaction is of particular interest in pharmaceutical applications. It plays a crucial role in the synthesis of more than 25% of commercially available drugs and similarly bioactive products with anticancer, antifungal, and antibacterial properties.127 However, a large amount of waste is usually produced during the amidation process, resulting in environmental and economic concerns. Enzymatic amidation was proposed as an alternative to address this challenge.128 Furthermore, new approaches with interesting mechanistic pathways have also been presented. For instance, Srivastava et al. reported a state-of-the-art green approach for amidating carboxylic acids using a photoredox catalysis technique. It acts by direct amidation using visible light and eosin Y as a catalyst and represents a cheap and eco-sustainable system. This technique can be used at room temperature. Hence, this novel approach enables amide bond formation, even under physiological conditions (Figure 3).126

Figure 3.

Sustainable amidation of carboxylic acids under mild conditions. (a) Schematic illustration of the amidation process using visible light (green LEDs). (b) The mechanism of amidation of carboxylic acids with amines in the presence of visible light and eosin Y.126 Adapted with permission from ref (126). Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

2.4. Oxidation

Oxidation of PSAs may occur on free primary alcohol functional groups or by oxidative cleavage of 1,2-diols. Using chemical or enzymatic reactions, primary alcohols in the C6 position can be oxidized to aldehyde or carboxylic acid (i.e., containing a uronic acid residue). The discovery of a stable aminoxyl radical (e.g., (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO)) allowed researchers to oxidize the primary alcohol on PSAs through a regioselective reaction to get polyuronic acids.129,130 TEMPO-mediated oxidation, in the presence of a primary oxidant such as sodium hypochlorite, selectively converts the primary alcohols of PSAs into carboxylic acid functional groups.131

Oxidation of PSAs can increase their reactivity, induce bioactivity, improve biostability, and modify their physical properties.132,133 Reactive functional groups, such as aldehydes generated from main chain oxidation, can be leveraged for further chemical modification of PSAs or for cross-linking purposes, particularly in the fabrication of injectable hydrogels.134 Furthermore, the degree of oxidation can be controlled to adjust the degradation behavior of PSAs.135

Reactive aldehyde functional groups can be used for further chemical modifications. For example, reductive amination of aldehydes can be performed using hydrogen as a reductant. Using a kind of one-pot, two-step technique, reductive amination can be done at 50–100 °C utilizing molecular dihydrogen and manganese pyridinyl-phosphine as reductant and precatalyst, respectively, with a high yield of 90%.137 Additionally, Mendoza et al. suggested a one-pot reaction for oxidizing cellulose that utilizes a combination of sodium periodate, TEMPO, NaClO, and NaBr. These oxidants synergistically form oxidized 2,3,6-tricarboxycellulose in water-soluble and water-insoluble fractions, depending on the periodate concentration. Their results showed that increasing the concentration of periodate enhances cellulose crystallinity, and the degree of substitution (DS) regulates the solubility of carboxylated cellulose (Figure 4).136

Figure 4.

Adjustable one-pot cellulose oxidation. (a) Illustration of (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO)-periodate oxidation of cellulose, which forms water-insoluble and water-soluble carboxylated fractions, which synergistically produces oxidized 2,3,6-tricarboxycellulose as a function of periodate concentration. (b) Presentation of selective oxidation (for cellulose). (A) TEMPO/sodium hypochlorite/sodium bromide oxidation at pH = 10.5. (B) Sodium periodate reaction. (C) combination of TEMPO/sodium hypochlorite/sodium bromide oxidation and sodium periodate reaction.136 Adapted with permission from ref (136). Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

2.5. Nucleophilic Displacement Reactions

Typically, organic synthesis requires the use of a protecting group strategy that enables selective functionalization. However, some limitations exist (e.g., multiple steps and cumbersome procedures) relevant to regio- or chemo-selective synthesis. This highlights the importance of atom economy in organic synthesis.136 As discussed earlier, the oxygen atoms in PSAs serve as nucleophiles and react with an alkylating agent to produce ethers/esters. However, alcohols can attack saccharides, which serve as electrophiles. For this purpose, nucleophilic displacement of groups containing nitrogen (e.g., amines and azides) or sulfur (e.g., thiols) is carried out, which is of interest for click chemistry.8 For example, synthesizing 6-amino-6-deoxycellulose without any protecting groups involves a nucleophilic substitution of the tosyl group with sodium azide. In one study, regioselective and complete iodination was carried out by nucleophilic substitution of the tosyl functional group at 60 °C.138 Interestingly, Hamdaoui et al. reported a novel method of synthesizing cellulose-l-methionine with strong antibacterial activity. They utilized an esterification reaction of microcrystalline cellulose with tosyl chloride, completed by a nucleophilic displacement reaction. In this reaction, displacement of the tosyl group was done by l-methionine, an amino acid, as illustrated in Figure 5.139

Figure 5.

Innovative approach for the synthesis of antibacterial cellulose derivatives. Schematic representation of the reaction pathway for l-methionine-modified cellulose using nucleophilic displacement.139 Reproduced from ref (139). The copyright is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 2021, Hindawi.

2.6. Grafting Reactions

Grafting reactions are a class of chemical reactions that conjugate small molecules and oligomers/polymers onto PSAs’ main chains to introduce new properties into the original PSAs. Grafting is a process that significantly enhances the chemical versatility of PSAs. It involves attaching polymerizable and functional monomers onto PSA chains to create interpenetrating polymer networks (IPNs) or stimuli-responsive PSAs. For instance, grafting gallic acid to CMCS enhances antioxidation activities and protects against peroxide-induced oxidative damage.140 In addition, grafting peptides to dextran has provided a platform with a more accurate endosomal release profile.141 Furthermore, a starch–cellulose hydrogel grafted with N-maleoyl-β-alanine (MAA) is another example of such a reaction. A biocompatible platform was designed for the controlled release of 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) using a combination of the Diels–Alder click reaction and photopolymerization, as shown in Figure 6.142 It is worth mentioning that grafting with catechol-containing molecules (e.g., dopamine and caffeic acid) endows PSAs with wet-adhesive properties, while grafting with alkyl chains (e.g., fatty acids) produces PSAs with hydrophobicity.143,144

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration of the mechanism of starch–cellulose interpenetration network formation. (a) Raw materials. (b) The mechanism for forming the first network. (c) The mechanism for forming the second network.142 Reproduced with permission from ref (142). Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

In addition to grafting PSAs with small molecules, grafting with oligomers has attracted much attention. For example, cationic PSAs with grafted oligomers are exciting materials for making nonviral vectors for gene delivery.145 These cationic polymers can enhance transfection efficiency through strong electrostatic interactions (or complexation) with DNA, which is negatively charged. Various oligoamines (e.g., spermin) can be grafted onto the PSA backbone. For example, dextran–spermine conjugates are efficient nonviral vectors for gene delivery.146 Reductive amination is the most critical strategy for making amines, such as in pharmaceuticals.147 For example, monoquaternary (MQ) ammonium oligoamines were grafted to OD and used for gene delivery.148 Furthermore, reductive amination can create PSA–protein conjugates.149

The grafting of oligomers and polymers onto the backbone of PSAs is typically categorized into two main strategies: graft-to and graft-from. This process results in hybrid polymers that inherit properties and functionalities from both the constructing polymers and the PSAs.150 In the graft-to strategy, a polymeric material is attached to the PSA backbone via reactive sites, such as clickable moieties.151 For instance, grafting-to has been employed to confer antibacterial properties to chitosan by grafting antimicrobial peptides (AMP) through a photoclick reaction.152 On the other hand, the grafting-from strategy involves polymerizing a monomer from reactive sites along the main chain of PSAs. For example, grafting poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) from PSA derivatives can impart thermosensitive properties to the resulting polymer.153 Controlled radical polymerization (CRP) techniques, including Nitroxide-mediated polymerization (NMP), atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP), and reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT), are commonly used for these purposes.154−156 These CRP methods facilitate the growth of well-defined polymer chains with high density, allowing precise control over polymer length, graft density, chemical composition, and topology. Utilizing these techniques has opened up new avenues for customizing PSA-based materials.148,157,158

Although molecular-scale modification of PSAs is a critical step toward their real-world biomedical application, complementary modifications are also necessary. Many of their chemical, biological, or mechanical features can be changed using modification techniques, such as physical, biological, and chemical modification. The following section is a comprehensive presentation of different modification processes crucial to tailor-making PSAs with desirable properties for biomedical applications.

3. Strategies for PSA Modification

3.1. Physical Modification

Physical modification aims to induce changes in the molecular structure of PSAs, such as reducing molecular weight, via physical triggers. PSAs with a reduced molecular weight typically show increased water solubility and bioactivity. A physical modification strategy can enhance the solubility of CS, starch, and cellulose. For example, the water solubility of CS at neutral pH is essential for designing drug carriers and tissue scaffolds. Three main strategies exist for the physical modification of PSAs: ultrasonic disruption, microwave exposure, and radiation-induced physical modification. In ultrasonic disruption, low- or high-frequency sound waves create mechanical vibrations that induce chemical bond cleavage. In other words, the energy transferred via ultrasonic waves results in vibration in chemical bonds, which ultimately leads to the clipping of covalent bonds in the chemical structure of PSAs. Cleavage of chemical bonds in the PSA backbone results in PSAs with lower molecular weights and enhanced water solubility.159,160

Microwave exposure is another facile physical modification strategy that can save even more time and energy than the above approach. Microwave exposure, like ultrasonic disruption, also improves the water solubility and biological activity of PSAs by breaking chemical bonds and reducing molecular weight. Instead of using mechanical waves, microwave exposure uses electromagnetic waves to transfer energy to chemical bonds throughout the structure of the PSA. Specific chemical bonds absorb specific spectra of electromagnetic waves, producing vibrational and rotational motions. These motions can result in bond cleavage and can increase local temperature via a frictional phenomenon, which eventually reduces the molecular weight of PSAs.161

The third physical modification strategy is known as radiation-induced treatment. Instead of electromagnetic waves of longer wavelengths, this technique utilizes high-energy radiation such as γ rays to induce chemical bond cleavage in PSAs. Radiation-induced treatment produces low molecular weight fragments of PSAs, which possess enhanced water solubility and antioxidation activities.162 Cobalt-60 (60Co), a well-known radioactive isotope of cobalt, is the most frequently used gamma-ray source in this technique.

3.2. Chemical Modification

Chemical modification of PSAs refers to a process where small molecules or macromolecules induce bond cleavage and/or formation in the chemical structures of PSAs. Utilizing biological macromolecules for chemical modification represents a strategy within this class of modifications. The biological modification of PSAs is considered equivalent to enzymatic modification. Enzymatic modification of PSAs involves chemical bond cleavage or chemical transformation using various enzymes, such as hydrolases and transferases.163 Compared to chemical modification, an enzymatic modification strategy is more specific, produces less waste, and possesses higher efficacy.164,165 Moreover, it results in a more uniform degradation along the chemical structure of the PSA. Although enzymatic modification is a favorable process for PSA modification, it is limited to some specific types of PSAs and represents a limited number of modifications. However, enzymatic modification is an excellent alternative to chemical modification, which often involves the use of toxic materials.166,167

Advancements in modern organic chemistry have driven chemical modification of PSAs, leading to new possibilities for creating chemically modified PSAs with enhanced versatility. Section 2 delves into the fundamental chemistry behind the chemical modification of PSAs, detailing specific and commonly used methods for incorporating specialized functional groups. These chemical modifications introduce unique characteristics to PSAs, facilitating the creation of customized formulations, as summarized below.

3.2.1. Sulfation

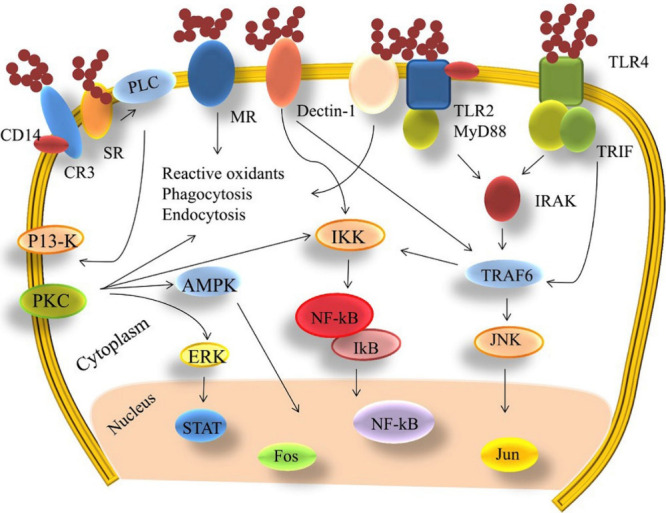

Sulfation is one of the most utilized chemical modification strategies for PSAs. It includes the chemical attachment of a sulfate group to a hydroxyl group on the pyranose ring of PSAs. Sulfation can enhance the existing bioactivities of PSAs or can introduce new functionalities, such as antiviral, antioxidant, and antitumor activities. For example, marine-derived OSA/PSA (e.g., carrageenans, alginates, and fucans) and their sulfated derivatives usually exhibit antiviral activities.168In vivo studies have shown that sulfated alginate possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-immunogenic properties.169 Recent studies have shown that heparin, a sulfated PSA known for its anticoagulant properties, exhibits remarkable binding affinity to the spike protein (S-protein) of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).170 Furthermore, in vitro investigations have demonstrated that specific sulfated PSAs possess high binding affinity to S-proteins of SARS-CoV-2, thus displaying antiviral activity.171 These sulfated PSAs interfere with S-proteins, which bind to heparan sulfate coreceptors on host cells, thereby preventing viral infection.172 Moreover, sulfated PSAs demonstrate antitumor activity by influencing various pathways involved in tumor growth and progression.173 They interfere with the cell cycle progression of cancerous cells, leading to tumor cell cycle arrest and inhibiting their growth, division, and uncontrolled proliferation. Additionally, sulfated PSAs exhibit antiangiogenic effects, induce apoptosis, and modulate the immune response, all contributing to their ability to inhibit tumor growth.174−176 Sulfated PSAs typically exhibit immunomodulatory activity and affect various signaling pathways, as depicted in Figure 7.177 Several sulfated PSAs, such as heparin or fucoidan, have the capability to directly bind to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and myeloid differentiation factor-2 (MD-2).178 This binding of sulfated PSAs to the TLR4-MD-2 complex leads to the activation of receptors, subsequently initiating downstream signaling cascades, as depicted in Figure 7. Similarly, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), components of the cell wall in Gram-negative bacteria, can also trigger the TLR4 and downstream signaling pathways.179 Thus, sulfation of PSAs enhances their bioactivity by facilitating interaction with biomacromolecular receptors on the plasma membrane, ultimately resulting in the activation of various intracellular signaling pathways.

Figure 7.

Immunomodulatory activity of sulfated PSAs. Schematic illustration of sulfated polysaccharides (PSAs)-induced regulation of functioning and metabolism of immune cells by activating signaling pathways involved in macrophage activation; CD14: a cluster of differentiation antigen 14; CR3: complement receptor 3; Dectin-1: dendritic cell-associated C-type lectin-1; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinase; IKK: inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase; IRAK: interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase; IκB: inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B; JNK: Jun N-terminal kinase; MR: mannose receptors; MyD88: myeloid differentiation factor 88; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; PI3-K: phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; PKC: protein kinase C; PLC: phospholipases C; SR: scavenger receptors; STAT: signal transducers and activators of transcription; TLR2: Toll-like receptor 2; TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; TRAF6: tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; TRIF: Toll/IL-1 domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon β.177 Reproduced with permission from ref (177). Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

Naturally occurring sulfated PSAs (e.g., chondroitin sulfate, carrageenan, and fucadion) play essential roles in biological systems. In addition, the sulfation of GAGs strongly affects human health conditions.180 GAGs are anionic linear PSAs and have been observed in all animal tissues. They affect the physical properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and tissues and modulate cells’ biological functions. Intrinsic negative charges originate from sulfate functional groups in all GAGs except for HA. Extracellular signals are modulated by sulfation, while phosphorylation is involved in intracellular signal transduction.181 GAGs play critical roles in many biological processes, a consequence of their interactions with many different proteins. However, many PSAs fail to mimic GAGs in the ECM (e.g., heparin) in terms of interactions with cells and other biomolecules. Sulfation may help PSAs in better mimicking the properties of GAGs, which are essential for applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. For example, sulfated alginates mimic the properties of heparin, making them comparable to heparin analogs.182 Sulfation of GAGs, a posttranslational modification process, modulates cell signaling pathways and mediates interactions with other cells or nearby ECM. It is worth mentioning that sulfation patterns of GAGs (known as sulfation code) affect various biological processes at different levels.183 Sulfated GAGs can be divided into four classes based on the primary monosaccharide unit and sulfation pattern: 1) HA, 2) chondroitin sulfate or dermatan sulfate (stereoisomers), 3) KS, and 4) heparin or heparan sulfate.184

Heparin has the highest degree of sulfation among GAGs, which endows it with a high number of interactions with various proteins. Sulfated GAGs (e.g., heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate) are anionic linear PSAs that play essential roles in animal tissues; they are ubiquitous in ECM and cell membrane, serve as structural components in ECM and act as receptors/coreceptors via electrostatic interactions with proteins. Chondroitin sulfate is a sulfated GAG and a critical structural component of cartilage with high compression resistance.185 Dermatan sulfate is another GAG found in the skin, lung blood vessels, and heart valves, playing roles in wound healing, cardiovascular disease, and infection.186 KS is a sulfated GAG found in cartilage, bone, cornea, and the central nervous system.187 These PSAs are highly hydrated and can absorb mechanical vibrations. Heparan sulfate (HS) octadecasaccharide was found to show hepatoprotective activity against acetaminophen-induced acute liver failure.188−190

3.2.2. Carboxymethylation

Carboxymethylation is a chemical modification strategy in which some of the hydroxyl groups on sugar units of PSAs are substituted with carboxymethyl groups (−CH2–COOH). It includes a facile chemical process that utilizes low-cost reagents to modify PSAs. Increased water solubility and enhanced bioactivity are the general features of carboxymethylated PSAs.191 Compared to sulfation, carboxymethylation benefits from process simplicity, low-cost raw materials, and minor toxic waste production.192,193 Kappa-carrageenan (KC) is a sulfated PSA that shows antitumor and immunomodulatory activities.194 This anionic linear PSA can create double-helix structures when interacting with divalent cations.195 The carboxymethyl functionality enhances the bioactivities of KC, which includes antiproliferative, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities, and alters its rheological properties in solutions.196

3.2.3. Acetylation

Acetylation is typically utilized to modify PSA side chains, resulting in a significant enhancement in solubility. In addition, acetylation is an essential posttranslational modification related to a wide range of biological processes, such as gene regulation.197 For example, CS is a linear heteropolysaccharide obtained by the deacetylation of chitin. The degree of acetylation of CS affects its physicochemical properties, biocompatibility, biodegradation, and cell interaction, highlighting the importance of the acetylation of PSAs.198 In addition, the anticoagulant activity of heparin pentasaccharide is drastically reduced upon acetylation.199 The acetylation pattern has also been found to affect the bioactivity of partially acetylated CS or chitosan oligosaccharide (COS), regardless of the degree of acetylation or the degree of polymerization.200−202 Cellulose acetylation results in water-soluble cellulose acetate, one of the most-used cellulose derivatives. The negligible solubility of cellulose in aqueous media or organic solvents is an obstacle to its chemical modification. Although cellulose is typically insoluble in most solvents, it can be dissolved in certain ionic liquids (ILs). These ILs can then be used to acetylate cellulose and produce high molecular weight cellulose acetate.203,204

3.2.4. Phosphorylation

Phosphate groups bearing electric charge can alter the solubility and chain conformation of PSAs. It should be noted that the strong acids used in the phosphorylation process may result in PSA degradation. It has been revealed that modification by phosphorylation enhances the antiaging effect of a PSA isolated from Trichosanthes peel.205 Phosphorylated GAGs are resistant to GAG-specific glycosidases.206 In addition, enhanced antioxidant activity was observed for phosphorylated PSAs isolated from different natural resources such as garlic, ginseng, and pumpkin.207−209 Various chemicals, such as phosphoric acid or anhydride phosphoric, phosphate, and phosphorus oxychloride, have been utilized in the phosphorylation of PSAs. For instance, Jiang et al. used a mixture of sodium trimetaphosphate and sodium tripolyphosphate to synthesize phosphorylated ulvan (a cell wall PSA).210In vivo studies on mouse models revealed that ulvan phosphorylation enhances its antioxidant and antihyperlipidemic properties.211 Although CS acts as an osteoconductive PSA, its osteoconductive properties can be improved through phosphorylation.212,213 Additionally, it is worth mentioning that, based on results from Cao et al., several PSAs derived from Amana edulis showed great antioxidant potential not only after phosphorylation but also after sulfation and carboxymethylation.214 Furthermore, it was recently revealed that influenza A viruses can bind to phosphorylated glycans from the human lung.215

3.2.5. Selenylation

Selenium (Se), as a micronutrient, supplies this essential trace element to the human body and other living organisms. Selenoproteins, containing selenocysteine residues, provide various pleiotropic effects, such as antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Se contributes to the structure of Se-dependent antioxidant enzymes (e.g., glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase), which protect cells against oxidation induced by free radicals.216 Se deficiency can weaken the immune system and increase mortality rates. In contrast, maintaining an adequate level of Se in the body can have antiviral and antitumor effects, and it may also reduce the risk of autoimmune thyroid disease.217,218

Selenylation of PSAs significantly increases their antioxidant, anticancer, and antidiabetic activities, as well as their antimetal-poisoning, immunomodulatory, and hepatoprotective properties.219,220 However, natural resources for Se-containing PSAs are minimal (e.g., Cucurbita pepo L. and Ganoderma lucidum) and contain very trace and insufficient Se content in their structure.220 Despite some successful results, adding inorganic Se-containing compounds (e.g., Na2SeO3) to the culture media has many complications.221 The most well-accepted selenylation process uses a combination of diluted nitric acid and Na2SeO3 to produce H2SeO3in situ, followed by selective esterification of primary OH groups on sugar units of PSAs.222,223 Excellent antioxidant, antitumor, and antidiabetic properties were observed for selenylated PSA isolated from sweet potato tuber.224 Additionally, it was revealed that selenylation of PSA extracted from Ulmus pumila L. (PPU) significantly enhanced the antioxidant activity of PPU.225 It is worth stating that PSAs themselves, as bioactive macromolecules, can be used as stabilizers for the fabrication and delivery of organic Se to the human body.226

3.2.6. Alkylation

Alkylation is a chemical modification that improves solubility, gel strength, and antibacterial activity. Among different PSAs, alkylation is most frequently used with pectin and can be classified as either methoxylation or long-chain alkylation. Methoxylation brings the minimum number of carbons within the chains, while long-chain alkylation usually connects more carbons to the carboxyl groups of pectin. A literature overview indicates that the physicochemical properties and functional features of the obtained PSAs are different for these alkylation reactions.227 Liu et al. reported that the molecular weight of alkylated pectin is affected by DS and degradation.228 They also showed that the random coil chain conformation in pectin is transformed into a spherical conformation for alkylated pectin with a higher DS. Moreover, they found that the gel strength of pectin was increased after the alkylation reaction.228 Yataka et al. studied the effect of alkyl chain length on the self-assembly of alkylated cellulose oligomers.229 They revealed that the self-assembly and allomorphs of cellulose oligomers critically depend on the alkyl chain length. Alkyl chains significantly affect the intermolecular interactions between different cellulose chains, leading to modified assemblies and diverse multidimensional structures. This is of interest for controlling the morphology and crystal structures of these cellulose derivatives. Alternatively, alkylation using alkyl halides, in the presence of sodium hydroxide and a catalyst, proceeds under mild reaction conditions, utilizes low-cost reagents and enables the creation of a variety of alkylated monosaccharides that can be polymerized to alkylated OSAs/PSAs.230Table 2 summarizes different types of chemical modification used for PSAs and the properties of the obtained products.

Table 2. Approaches for the Chemical Modification of Different Types of Polysaccharides (PSAs) and the Impact of Their Structure and Performance Are Essential for Biomedical Applications.

| Modification Strategy | PSA Type | Results | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxylation | Kappa-carrageenan | • Increased viscosity in water and decreased viscosity in synthetic human sweat | (196) |

| • Higher viability and lower cytotoxicity for human adipose-derived stem cells (hADSCs) | |||

| • No hemolytic activity in human red blood cells (RBC) | |||

| • Increased antioxidant activity | |||

| • Antibacterial activity | |||

| Chitosan | • Enhanced water solubility at various pH | (85) | |

| • Support cell growth and tissue regeneration | |||

| • Improved bioactivity, including antimicrobial, anticancer, antitumor, antioxidant, and antifungal | |||

| Mutan | • Higher thermal stability | (231) | |

| • Enhanced solubility | |||

| • Antioxidative, radical-scavenging activity | |||

| Sulfation | Alginate | • Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-immunogenic properties | (169) |

| • Free radical–scavenging properties | |||

| Chitosan | • Antimicrobial activity | (190) | |

| • Higher solubility | |||

| • Less chain depolymerization | |||

| • Higher yield | |||

| • Greater thermal stability | |||

| Polysaccharide isolated from Gracilaria caudate (a marine alga) | • Reduced hypernociception and edema | (232) | |

| • Reduced inflammatory response | |||

| • Great option for treating arthritis | |||

| Polysaccharide isolated from Myriophyllum spicatum L. | • Immunostimulatory effect | (233) | |

| • Heterogeneous molecular weight | |||

| • Activated macrophages | |||

| Acetylation | Cellulose | • Enhanced crystallinity, up to 70% | (190, 234) |

| • Enhanced hydrophobicity | |||

| • Dispersible in water and other organic solvents | |||

| Chitosan | • Higher solubility | (235) | |

| • Lower molecular weight | |||

| • Random distribution of functional groups | |||

| Phosphorylation | Polysaccharide isolated from Ulva pertusa | • Enhanced antioxidant and antihyperlipidemic properties | (210) |

| Chitosan | • Improved osteoinduction | (213) | |

| Polysaccharides extracted from Pleurotus ostreatus | • Enhanced hepatoprotective effect | (236) | |

| Chitosan | • Improved osteoinduction | (213) | |

| • Large pore sizes (850–1097 μm), microroughness and thickness | |||

| • Low level of thrombogenicity | |||

| • Long degradation time | |||

| • Low cytotoxicity | |||

| Polysaccharide isolated from native ginseng | • Enhanced radical-scavenging ability (antioxidant activity) | (209) | |

| Polysaccharide isolated from pumpkin | • Enhanced antioxidant activity, scavenging ability to hydroxyl radicals | (208) | |

| Polysaccharide isolated from garlic | • Enhanced antioxidant activity | (207) | |

| • Scavenging hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anions | |||

| Radix Cyathula officinalis Polysaccharide | • Improved immune-enhancing activity | (237) | |

| • Increased secretion of cytokines | |||

| • Immune-adjuvant activity | |||

| Selenylation | Polysaccharide isolated from Momordica charantia L. | • Antidiabetic properties: reduced fasting blood glucose levels and enhanced insulin levels | (238) |

| • Improved antioxidant enzyme activities | |||

| • Preventing liver, kidney, and pancreatic islet damage in diabetic mice | |||

| Chinese angelica polysaccharide | • Enhanced immune-enhancing activity | (222, 223) | |

| Chuanminshen violaceum Polysaccharide | • Enhanced immune-enhancing activity | (239) | |

| Artemisia sphaerocephala Polysaccharide | • Immunomodulatory effect | (240) | |

| Polysaccharide isolated from Ulmus pumila L. | • Improved anti-inflammatory activity | (241) | |

| Polysaccharide isolated from Ulmus pumila L. | • Significantly enhanced antioxidant activity | (225) | |

| • Hydroxyl radical–scavenging activity | |||

| Mycelial PSA from Catathelasma ventricosum | • Enhanced antidiabetic activity by increasing selenium content | (242) | |

| • Damaged triple-helical structure | |||

| Cellulose | • Controllable morphology and crystal structure | (229) | |

| Pectin | • High stability | (227) | |

| • Long release time | |||

| • Good mechanical characteristics | |||

| Pectin | • Controllable degradation profile | (228) | |

| • Random coil conformation |

4. Tailor-Made PSAs for Biomedical Applications

Modifying the chemical structure of materials at the molecular scale can introduce specific features, such as stimulus responsiveness or bioactivity, and import new functionalities into conventional materials. Strategies such as introducing cleavable covalent bonds, functionalizing with molecular recognition motifs, inserting hydrophilic and hydrophobic segments in one (macro)molecule, grafting specific lipids or molecules onto polymer chains, and performing partial oxidation can be employed to create multifunctional materials with specific functionalities and bioactivities.243,244 These chemical modifications can be used to design new macromolecules from small molecules or to modify OSAs and PSAs. At higher length scales, the resulting multifunctional materials may exhibit new properties, including different self-assembly behavior, which can be leveraged to create advanced biomaterials.

Unprecedented progress in chemistry and materials science, including dynamic chemistry, clip chemistry, click chemistry, supramolecular chemistry, and CRP strategies, has made it possible to create novel biomaterials with customized properties and functionalities. The strength of these strategies can be utilized in the field of OSA/PSA to create multifunctional PSAs with dynamic behavior and customized properties. This approach has garnered attention from biologists and biomedical engineers, who can synergistically leverage the power of biology and chemistry to tackle some of the outstanding challenges in the biomedical field.

This section addresses the modification of PSAs to introduce tailor-made features. However, it is worth mentioning that biomaterials’ bulk properties are affected not only by chemical structure and composition but also by ordering and hierarchy at higher length scales, which can be dictated by thermodynamic equilibrium, kinetic trapping, or out-of-equilibrium self-organization.245,246 Even at higher length scales, we can observe properties or functionalities induced by naturally occurring (e.g., gecko feet) or artificial (e.g., metamaterials) microstructures. However, this section focuses on the chemical modification of the molecular structure of PSAs, rather than examining phenomena on a larger length scale.

4.1. Tailored Body/Immune Responses

The human body, including its organs, tissues, and individual cells, constitutes a highly dynamic microenvironment with a myriad of biomolecules engaged in continuous interactions.247 These interactions play a crucial role in coordinating various intracellular processes, facilitating cell–cell interactions, mediating receptor–ligand interactions, and triggering cellular movements. Cell interactions with other cells and biomaterials, such as the surfaces of DDSs or implanted devices, are mediated by a dense array of biomacromolecules, such as glycoconjugates, decorating the plasma membranes of cells.248 The interactions between cells or native biomolecules and biomaterials are primarily determined by the chemical structure of the biomaterials, ultimately influencing the in vivo fate of DDSs or tissue engineering scaffolds. For instance, the cytotoxicity, biocompatibility, and degradation behavior of biomaterials used in tissue scaffolds are predominantly influenced by interactions between immune cells or enzymes and the biomaterials.249

Drug delivery is one of the most critical research areas of biomedical engineering, especially cancer drug delivery.250,251 The efficient delivery of therapeutics primarily depends on delivery vehicles’ structural features and chemical composition. Smart DDSs should be able to target particular types of cells (e.g., cancer cells) and release therapeutics in a controlled and sustained manner. Additionally, they should pass through biological barriers (e.g., blood–brain barrier (BBB)) and evade the immune system. All of these features depend primarily on the interactions of cells or biomacromolecules with the constructing materials of delivery platforms. For example, decorating DDSs with targeting ligands is a popular strategy for making targeted DDSs that can target cancer cells (Section 4.7). DDSs can be coated with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) layer to evade immune cells before reaching the target site, such as tumor tissue. Similarly, it is possible to graft PEG onto PSAs to make a DDS that can evade the immune cells. These surface treatment strategies are also applicable to tissue engineering constructs. Similar to drug delivery systems, the surfaces of tissue scaffolds are exposed to the biological environment and may undergo events such as protein adsorption and detection by the immune system as potentially harmful. Therefore, the design of the composition and surface modification of tissue engineering constructs is critical for preventing immune responses.252,253 PSAs play a valuable role in the formulation and surface modification of tissue scaffolds and wound dressings, as they have the ability to modulate immune responses.254,255

A protein corona is a tightly packed layer of protein that is adsorbed onto nanoparticles to form a coating around them, as shown in Figure 8.256 A variety of proteins with molecular masses in the range of 10–100 kDa can contribute to the protein corona, including albumin, fibronectin, and globulin in the blood. The protein corona phenomenon can significantly affect nanoparticles’ identity and final fate. Various ligands, stealth polymer coatings, and protein shields have been used to overcome this challenge and minimize protein corona formation.257 Formation of protein coronas around PSA-based nanoparticles is possible via protein–PSA interactions. In particular, CS-based nanomedicine, which is surrounded by a cationic surface, adsorbs different cells and proteins through electrostatic interactions (due to the negative charge on proteins’ surfaces). This phenomenon can limit the bioavailability and clinical applications of CS-based DDSs. Hence, overcoming the challenges associated with protein adsorption onto nanoparticulate delivery platforms is of utmost importance in biomedical engineering.258 The nonspecific interactions related to biofouling can alter a DDS’s pharmacokinetic properties function. Given the above data, a severe demand exists for a deep study of tailoring PSA-based nanoparticles’ interactions with their drug delivery media.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of adsorption of abundant, negatively charged proteins (e.g., albumin) onto nanoparticles, ultimately leading to protein corona formation. Based on the Vroman effect, higher molecular weight proteins replace the soft layer, which leads to the formation of a hard corona.258 Reproduced with permission from ref (258). Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

Preventing biofouling is a critical challenge in implanted devices, such as tissue engineering scaffolds, where the accumulation of biological materials on the surface can interfere with their inherent function. When the body detects potentially harmful pathogens or materials, a series of physiological processes is triggered to protect against these foreign substances, collectively known as immune responses. The immune system comprises two main components: the innate and adaptive immune systems.259 The innate system acts as the first line of defense, providing a nonspecific immune response that is immediately activated upon threat detection. It includes physical barriers such as the skin and mucous membranes, as well as specific cells like phagocytes. Additionally, it initiates inflammatory responses and recruits immune cells to the site of infection. Implantation of a biomaterial activates the innate immune response, leading to the activation of immune cells that secrete factors to call additional immune cells to the infection site. These secreted factors and subsequent processes constitute the initial stages of the biofouling process, which is further complicated by the expression of specific molecules by microbes.260 On the other hand, the adaptive immune system elicits a specific immune response that develops over time following antigen detection. This system involves specialized immune cells such as B cells and T cells, as well as antibodies that target specific antigens like viruses and bacteria.261 Processes such as macrophage engulfment through phagocytosis and renal clearance are crucial for clearing foreign bodies from the body.

The biofilm formation process begins when a device (e.g., pacemaker) or tissue scaffolds (Ti mesh) is implanted. PSAs can be chemically modified to make antibiofouling materials to protect implants and scaffolds from fouling. For example, dopamine–HA–HA conjugates were used as an antibiofouling coating for various substrates such as metals and polymers.262 Dopamine–HA coatings prevent protein adsorption and cell attachment on substrates using mussel-inspired chemistry.263 Alternatively, zwitterionic copolymers can be used to tailor the antibiofouling of PSAs. For example, methacrylated HA was in situ-gelled with a zwitterionic copolymer based on carboxybetaine methacrylate using a thiol–ene click reaction.264 The obtained PSA-based hydrogel with zwitterionic cross-linkers showed diminished protein adsorption. Recently, there have been several comprehensive reviews of ionically gelled PSAs intended for drug delivery applications.48,251

Antimicrobial materials are a class of materials that inhibit biofilm formation by killing bacteria. For example, grafting antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) onto PSAs can be a robust strategy for making antibiofouling PSA-based scaffolds. AMPs are small molecules that exhibit a broad range of antimicrobial properties. They are part of the innate immune system and are produced by cells in response to microbial infection. These positively charged peptides, which are typically amphiphiles, interact with and disrupt microbial membranes, resulting in antimicrobial effects.265 An example of an AMP is histatin, found in human saliva, which protects the oral cavity from pathogens.266

Methacrylated AMPs were grafted to dextran to make cationic peptidopolysaccharides with antimicrobial properties.267 In similar research, an AMP was grafted onto amino and hydroxyl functionalities on sugar units of CS via click reaction to make antibacterial coatings.268 The CS-g-AMP showed lower cytotoxicity against mammalian cells than did free AMP molecules.

4.2. Tailored Adhesiveness

It is essential to consider the adhesion of biomaterials to biological tissues, such as skin, mucus, bone, and other internal parts of the human body when designing tissue engineered scaffolds, medical devices, and surgical adhesives.269−271 The adhesion process involves multiple factors and can be mediated by various mechanisms, including covalent bonding, physical interactions (such as electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding), and mechanical interlocking.272,273 Additionally, protein adsorption acts as an interlayer or bridge between tissue and biomaterials, further facilitating adhesion. Understanding and tailoring these adhering mechanisms is essential for designing superior tissue engineering constructs.274 The ability to tailor tissue adhesiveness relies not only on the chemical composition of the biomaterials used but also on the surface topology of tissue engineering scaffolds.

Most internal organs and tissues are hydrated or covered by a highly hydrated mucus layer. Accordingly, wet adhesion is a prerequisite for tissue attachment, and designing wet-adhesive biomaterials is vital for these applications, as represented in Table 3. Mussel-inspired chemistry has been at the center of attention in developing wet-adhesive biomaterials.275 Some chemical functionalities, such as catechol, significantly increase the wet adhesion of tissue scaffolds, wound dressings, and surgical adhesives.276 Various physical and chemical interactions play vital roles in tissue-adhesive properties. Catechol moieties can chemically interact with amine and thiol functional groups on the outer surface of tissues. Furthermore, surface patterns also impact wet/dry adhesion.277,278 Surface chemistry, topology, and mechanics significantly affect the adhesion of hydrogels.279

Table 3. Tailor-Made Polysaccharides (PSAs), Applied Modifiers, Resulting Functionalities, Resulting Tissue-/Wet-Adhesive Properties, and Corresponding Biomedical Applications.

| PSA Type | Other Constituents/Functionalities | Properties (Processing, Physicochemical, Mechanical, Biomedical) | Application | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Catechol | • Thermosensitive | • Wound dressing | (143) |

| • Antibacterial | ||||

| • Promote angiogenesis | ||||

| • Adjustable mechanical properties via catechol degree of substitution | • Surgical adhesives | (284) | ||

| • High adhesive shear strength (64.8 kPa to porcine skin) | ||||

| Lauric acid | • Good physicochemical features | • Mucosal drug delivery | (285) | |

| • No cytotoxicity | ||||

| Chitosan | Gelatin | • Good adhesiveness | • Tissue adhesive for infected wound closure | (286) |

| • Antimicrobial activities | ||||

| • Good wound-healing properties | ||||

| Benzaldehyde-terminated Pluronic F127 and carbon nanotubes | • Desirable gelation time | • Treatment option for infected wounds | (287) | |

| • High water absorption | ||||

| • Stable mechanical features | ||||

| • Antimicrobial activities | ||||

| • Hemostatic properties | ||||

| • Good biodegradability | ||||

| Polyethylene glycol propionaldehyde | • Facile preparation | • Wound closure | (288) | |

| • Injectable | ||||

| • Fast gelation time | ||||

| • High adhesive strength | ||||

| • Low cytotoxicity | ||||

| • Great wound healing responses | ||||

| Oxidized konjac glucomannan | • Great tissue adhesiveness | • Wound healing | (289) | |

| • Great antibacterial activities | ||||

| Pyrogallol | • Good electrospinning capability | • Hemostasis applications | (290) | |

| • Good adhesiveness to wet media | ||||

| Methylenebis(acrylamide) | • Good swelling ratio | • Different biomedical applications | (291) | |

| • Good mechanical properties | ||||

| • Antibacterial | ||||

| Polyethylene glycol | • Rapid gelation | • Tissue adhesive devices | (292) | |

| • Great tissue adhesiveness | ||||

| • Hemostatic ability | ||||

| Glycol chitosan | 3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) propionic acid | • Tissue adhesiveness | • Wound dressing | (293) |

| • Antibacterial activities | ||||

| • Hemostasis ability | ||||

| • Controlled drug release | ||||

| Gelatin or chitosan | Poly(acrylic acid), N-hydrosuccinimide ester | • Perfect adhesiveness to wet tissue | • Sealant | (294) |

| Carboxymethyl Chitosan | Aldehyde hydroxyethyl starch | • Controllable gelation time | • Hemostasis applications | (292, 295) |

| • Controllable mechanical properties | ||||

| • Biocompatibility | ||||

| • Controllable degradation | ||||

| Oxidized sodium alginate | Polyacrylamide | • Mechanical stability | • Wound dressing | (296) |

| • High tensile strength | ||||

| • High stretchability | ||||

| • Great self-healing ability | ||||

| Agarose | Polyethylene glycol | • Fast gelation | • Wound dressing | (297) |

| • Good mechanical properties | ||||

| • High deformability | ||||

| • Short hemostasis time | ||||

| Dextran | Aldehyde group | • Strong blood absorption | • Hemostasis applications | (298) |

| • Strong tissue adhesiveness | ||||

| Levan | Chitosan and alginate | • Surface homogeneity | • Free-standing layer-by-layer film | (299) |

| • Great mechanical performance | ||||

| • Great biological features | ||||

| Chitin | Fibrin, gelatin | • Bioadhesive | • Surgical adhesives | (300) |

| • Hemostatic | ||||

| • Antibacterial |

Grafting catechol-containing molecules and short peptides onto PSAs has been a widely used strategy to tailor wet- and tissue-adhesive properties of PSAs. For example, Hasani-Sadrabadi et al. fabricated a cell-laden bioinspired hydrogel based on dopamine-modified methacrylated alginate for craniofacial bone tissue regeneration.280 As shown in Figure 9, they grafted dopamine onto methacrylated alginate using carbodiimide chemistry. Methacrylate functional groups enabled photo-cross-linking, while catechol moieties of dopamine endowed the hydrogel with a wet-adhesion feature. It was further modified with a short peptide mimicking collagen to improve cell adhesion. The hydrogel can be cross-linked physically by adding Ca2+ cations or chemically via oxidizing dopamine moieties on alginate chains. In addition, methacrylate functionality on alginate chains enables cross-linking via radical polymerization.279,281 Hydroxyapatite microparticles (HAP MPs), which can induce osteogenic differentiation, were incorporated into gingival mesenchymal stem cells (G-MSCs). The obtained injectable mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-laden hydrogel showed osteoconductive, wet-adhesive, and biodegradation properties, as well as adjustable mechanical properties, making it appealing for bone tissue engineering in the oral cavity. In vivo investigations in a rat model showed that MSC-laden adhesive hydrogels can completely regenerate bone tissue around dental implants.280

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of a synthetic pathway for cell-laden and injectable alginate-based hydrogel with tailored wet and tissue adhesion properties.280 Reproduced with permission from ref (280). Copyright 2020, The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A hydrocaffeic acid-grafted CS with tailored wet-adhesive properties (Gel1) was designed and used as a hemostatic, adhesive wound dressing because of excellent adhesiveness and inherent hemostatic capability.282 In addition, CS was modified with lactic acid, resulting in hydrophobically modified CS lactate (hmCS lactate) with tailored hydrophobic properties. Integration of hydrocaffeic acid-grafted CS with hmCS lactate in ratios of 4:1 (Gel2) and 2:1 (Gel3) introduced amphiphilic features into the obtained PSA, thereby enhancing the hemostatic capability of CS. Catechol functionalities on hydrocaffeic acid induce wet adhesion to CS and enhance its antimicrobial properties. As shown in Figure 10, modified CS with tailored properties is an adhesive hydrogel with excellent anti-infective and antibleeding features.

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of in vitro and in situ characteristics of chitosan (CS)-based adhesive gel as a hemostasis agent. (a) Blood clotting index (BCI) values at 7 min, (b) images of in vitro blood-clotting process at 7 min, (c) red blood cells (RBC)attachment percentages, (d) percentages of platelet adhesion, (e) photographs of in situ antibleeding effects, (f) total blood loss mass, and (g) hemostasis time in response to CS-based adhesive gels (Gel1, Gel2, and Gel3).282 Reproduced from ref (282). Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

In a similar vein, phosphate groups play a crucial role in adhesion to inorganic materials. Accordingly, adhesive materials for bone/tooth tissue engineering could be designed based on phosphate-bearing PSAs to tailor their adhesiveness to hard tissues. For example, phosphocreatine-modified CS was used to fabricate porous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering with excellent adhesiveness behavior.280,283

4.3. Tailoring Mechanical Properties

Improving and tuning the mechanical properties (e.g., stiffness, tensile strength, flexibility, and elasticity) of PSA-based biomaterials is of utmost importance in many biomedical applications, such as fabricating tissue engineering constructs.301 For instance, tuning the mechanical properties of a hydrogel (e.g., modulus) so that it conforms to surrounding tissue is vital for injectable hydrogels. In addition, the time-dependent mechanical properties of injected or implanted scaffolds are essential for maintaining their integrity over the defined time needed to effectively deliver their payload (e.g., cells, therapeutics).