Abstract

Leukemia and lymphoma induced by feline leukemia viruses (FeLVs) are the commonest forms of illness in domestic cats. These viruses do not contain oncogenes, and the source of their pathogenic activity is not clearly understood. Mechanisms involving proto-oncogene activation subsequent to proviral integration and/or development of recombinant viruses with enhanced replication properties are thought to play an important role in their disease pathogenesis. In addition, the long terminal repeat (LTR) regions of these viruses have been shown to be important determinants for pathogenicity and tissue specificity, by virtue of their ability to interact with various transcription factors. Previously, we have shown that, in the case of Moloney murine leukemia virus, the U3 region of the LTR independently induces transcriptional activation of specific cellular genes through an LTR-generated RNA transcript (S. Y. Choi and D. V. Faller, J. Biol. Chem. 269:19691–19694, 1994; S.-Y. Choi and D. V. Faller, J. Virol. 69:7054–7060, 1995). In this report, we show that the U3 region of exogenous FeLV LTRs can induce transcription from collagenase IV (matrix metalloproteinase 9) and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) promoters up to 12-fold. We also show that AP-1 DNA-binding activity and transcriptional activity are strongly induced in cells expressing FeLV LTRs and that LTR-specific RNA transcripts are generated in those cells. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1 and -2) by the LTR is an intermediate step in the FeLV LTR-mediated induction of AP-1 activity. These findings thus suggest that the LTRs of FeLVs can independently activate transcription of specific cellular genes. This LTR-mediated cellular gene transactivation may play an important role in tumorigenesis or preleukemic states and may be a generalizable activity of leukemia-inducing retroviruses.

Feline leukemia viruses (FeLVs) are type C retroviruses of the domestic cat species, which are contiguously transmitted in natural environments. They are capable of inducing either acute cytopenic diseases such as anemia and T-cell depletion or, after prolonged latency, proliferative diseases such as leukemia and lymphoma in this animal population (60). The FeLV family consists of three known subgroups, FeLV-A, FeLV-B, and FeLV-C, defined by virus interference and neutralization patterns. The subgroup composition of FeLV field isolates is A, AB, AC, and ABC (61). This pattern suggests that they are interdependent in vivo and that subgroup B and C viruses can be transmitted only as a phenotypic mixture with subgroup A. FeLV subgroups differ in their host range of infection in vitro. Replication of FeLV-A isolates is usually restricted to feline cells. FeLV-B and FeLV-C isolates also replicate well in mink, canine, and human cells, whereas only FeLV-C replicates in guinea pig cells (39, 57).

The mechanism by which FeLVs induce T-cell transformation is not well understood. These viruses do not contain oncogenes and do not acutely transform infected cells. In analogy to other oncogene-deficient leukemia viruses, promoter insertion and enhancer activation by means of provirus integration have been proposed as possible mechanisms of oncogenesis. Generation of recombinant viruses following infection has also been shown to play an important role in tumorigenesis induced by the FeLVs, as well as the murine leukemia viruses (MuLVs), through the higher replication competence of the recombinant viruses (51, 63, 64).

Genetic studies of MuLVs which induce T-cell lymphomas and erythroleukemias, and of FeLVs, have established that sequences within the U3 region of the viral long terminal repeats (LTRs) are necessary for leukemogenicity and encode determinants for tissue tropism and latency (8, 9, 11, 21, 48, 51, 58). The U3 region consists of multiple nuclear protein-binding sites that are conserved among murine, feline, and other C-type retroviruses (30, 32, 65). It has been suggested that the U3 regions exert their role in oncogenesis through tissue-specific binding of nuclear transcription factor proteins to these sites.

Although these mechanisms play an important role in many tumors induced by leukemia viruses, a substantial proportion of such tumors do not show site-specific proviral insertions (71). It is thus possible that other, uncharacterized, virus-directed pathogenic mechanisms may be involved. We have earlier demonstrated that infection and transient or stable transfection of mouse fibroblasts and human lymphoid cells by Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MuLV) induce elevated expression of several cell surface antigens, cytokines, and collagenase IV (28, 41, 74). These elevations in cellular protein levels are the result of increased expression of the corresponding endogenous gene transcripts. We further demonstrated that the U3 region of the viral LTR alone was sufficient for transactivation of these genes (12, 13). We proposed that such cellular gene transactivation by Mo-MuLV could be another mechanism by which these viruses stimulate the requisite preneoplastic polyclonal proliferation of lymphocytes or other target cells, which is believed to be an important early event in the multistep process of leukemogenesis.

Since FeLV infection in cats often leads to the development of leukemia and lymphoma, and their LTRs are known to be important pathogenic determinants of disease, we investigated whether FeLV LTRs can induce cellular gene expression. We show here that FeLV, and the isolated FeLV LTR, can transactivate the expression of certain AP-1-inducible genes, the products of which are potentially important in tumorigenesis, such as collagenase IV and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1). We also show that FeLV infection or transient transfection of the FeLV LTR into feline embryo fibroblast AH927 cells or BALB/3T3 cells induces AP-1 DNA-binding activity and transcriptional activity. FeLV LTR expression activates intermediates of the Raf-1/MAPK signal transduction pathway, MAPK kinases 1 and 2 (MEK1 and -2), which appear necessary for activation of AP-1 by the LTR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and reagents.

Murine fibroblast cell lines BALB/3T3 and NIH 3T3 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% donor calf serum (DCS) (Sigma), 200 mM l-glutamine, and 100 U each of penicillin and streptomycin per ml. Feline embryo fibroblast line AH927 was the gift of P. Roy-Burman and was maintained in the same medium but with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Sigma). Kinase inhibitors PD98059 and SB203580 were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.).

Plasmids.

FeLV LTR chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) constructs p61B-CAT, p61C-CAT, and p61E-CAT were provided by Julie Overbaugh. The inserts in these plasmids came from FeLV molecular clones 61B, 61C, and 61E, respectively, and contained approximately 0.2- to 0.7-kb feline genome sequence flanking 5′ LTR, the entire U3 region, and the first 31 bases of the R region, up to the SmaI site (positions 1 to 372, with respect to FeLV-A clone 61E) of the 5′ FeLV LTR. These LTR-containing restriction fragments were inserted into the BglII site of the pSV40-CAT vector by using BglII linkers. 61B, 61C, and 61E are three molecularly cloned FeLV-A viruses from small intestine DNA of a domestic cat (no. 1161) artificially infected with the FeLV feline AIDS strain (22, 53). A 347-bp PstI-BglII fragment (PstI site at 34 bp down from the beginning of LTR) from these clones was subsequently cloned into the PstI-BamHI site of pTZ19U vector (United States Biochemicals), and the resulting plasmids were designated p61B-LTR, p61C-LTR, and p61E-LTR. An approximately 1.6-kb NsiI-EcoRI fragment from position 7795 of the virus genome to the EcoRI site of the vector in clone p61E (containing most of the transmembrane protein P15E, the entire 3′ LTR, and a small portion of feline genome) was subcloned into the PstI-EcoRI site of pSP72 (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) and was designated p61E-P15E/LTR (Fig. 1). pMoV9 is a cloned Mo-MuLV provirus (16), and pXFUX is a 3′ LTR construct from Mo-MuLV, both of which have been described previously (13).

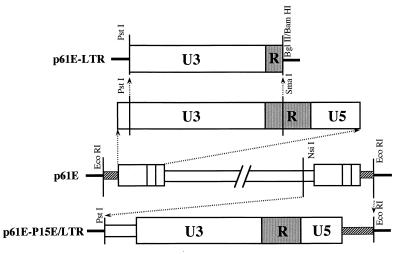

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the FeLV LTR expression vectors. The open and partially shaded boxes represent viral sequences, whereas the hatched boxes represent flanking genomic sequences. Thick lines represent vector backbone sequences. Construction of these and similar clones is described in Materials and Methods. Sequence lengths are not to scale.

The plasmid pCR3.1/61E-LTR-PK was constructed by cloning the insert of the p61E-LTR plasmid into the PstI and KpnI sites of the plasmid pCR3.1 (Invitrogen). EcoRI-digested and self-ligated pCR3.1 plasmid was used as a vector control in some transfections.

The reporter plasmid −517/+62 collagenase CAT (−517/+62 Coll-CAT) was the generous gift of P. Angel (4). The MCP-1 promoter-CAT construct (−543 JE-CAT) was the generous gift of A. J. van der Eb (69). A 2.1-kb major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I promoter-CAT construct (pKbHN-CAT) has been described previously (24–26, 28, 41, 74). The interleukin-6 (IL-6) promoter-CAT construct (−225 IL-6-CAT) was a gift of P. B. Sehgal (56). The IL-2 promoter-CAT construct (−585 IL-2-CAT) was the gift of E. Rothenberg. A CMV-Coll-CAT reporter plasmid used as a control in this study had the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter cloned 5′ to the −73 collagenase promoter-CAT construct (obtained from S. Choi). Another AP-1-inducible CAT construct bearing three consensus 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response element sites in tandem was the gift of M. Karin.

DNA transfection and CAT assays.

Cells were split from an actively growing culture onto 100-mm-diameter tissue culture dishes on the day before transfection and transfected with a CsCl-banded plasmid preparation by the DEAE-dextran method (47) with modifications. Briefly, plasmids were mixed with 4 ml of DMEM containing 250 μg of DEAE-dextran (molecular weight, 500,000; Sigma) per ml without serum or antibiotics, layered onto the cell monolayer, and incubated at 37°C for 3.5 h. Cells were then washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with dimethyl sulfoxide reagent (137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, 6 mM glucose, 21 mM HEPES [pH 7.1], and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide) for 90 s. Cells were washed in PBS and incubated in the presence of DMEM with DCS, antibiotics, and 1 μM chloroquine (Sigma) per ml for 1 h. Cells were then washed again in a small volume of PBS and incubated in the same medium without chloroquine. In some cases, transfections were also carried out with Lipofectamine Plus reagent from GIBCO-BRL (Gaithersburg, Md.), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed by quick-freezing and thawing three times, clarified supernatant was collected, and the protein concentration was measured. Transfection efficiency was monitored by cotransfection of 1 μg of an expression plasmid for green fluorescent protein (gift of B. Seed) for each plate. Equal amounts of protein from each transfected plate were then assayed for CAT activity with [14C]chloramphenicol and acetyl coenzyme A followed by thin-layer chromatographic separation of acetylated [14C]chloramphenicol (34).

Cell lines containing stably integrated FeLV LTRs were generated by transfecting pCR3.1/61E-LTR-PK. This plasmid itself contains a neomycin resistance gene expression cassette. BALB/3T3 cells were transfected with either pCR3.1/61E-LTR-PK or the pCR3.1 vector alone by the DEAE-dextran method as described above. Two days after transfection, cells were split at a low density (∼5,000 cells in 100-mm-diameter dishes) in the presence of G418 (0.4 mg/ml). G418-resistant cell colonies were pooled and passaged in the presence of G418.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Nuclear protein extracts were prepared by the hypotonic lysis method of Andrews and Faller (2). Briefly, cells were harvested from plates by being scraped with a sterile rubber policeman and washed in ice-cold PBS. The pellets were resuspended in a 20× volume of buffer A (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, and 0.05% Igepal [Nonidet P-40 substitute from Sigma]) and incubated on ice for 15 min. The suspension was then mixed thoroughly and microcentrifuged for 10 s. The pelleted nuclei were resuspended in 50 μl of extraction buffer C (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 420 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, and 25% glycerol) and incubated on ice for 30 min with periodic mixing. The nuclear extract was clarified by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge for 10 min at 4°C, aliquoted in a small volume, and stored at −70°C until used. Binding reactions were performed with 4 to 5 μg of nuclear protein extract in a total volume of 20 μl in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 50 mM potassium glutamate, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, and 5% glycerol). The extract was first incubated with 4 μg of poly(dI-dC) on ice for 8 min to reduce nonspecific binding. 32P-labeled AP-1 oligonucleotide probe (5,000 cpm) was then added to the mixture, and incubation was continued on ice for another 25 min. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on a 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer (45 mM Tris-borate [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA), vacuum dried, and exposed to Kodak X-AR film for an appropriate length of time. The AP-1 consensus-binding site oligonucleotide was purchased from Promega and end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The labeled probe was heated at 90°C for 2 min and then allowed to anneal by being cooled down slowly at room temperature before use.

Immunoblotting.

Western immunoblotting was performed to detect levels of phosphorylated MEK1 and -2 in cells transfected with FeLV LTR or full-length proviral clones by using panreactive or phosphospecific MEK1 and -2 antibodies from New England Biolabs. Infected or transfected cells were scraped off the plate, washed once with PBS, and then lysed in cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% Igepal [Nonidet P-40 substitute from Sigma], 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg of aprotinin per ml, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride). Twenty micrograms of protein from each lysate was separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 to 2 h at room temperature. Blocked membranes were incubated in primary antibody (anti-MEK1 or -2 or anti-phosphospecific MEK1 or -2) at a 1:1,000 dilution in TBST containing 5% BSA overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody treatment was carried out at room temperature for 1 h at a dilution of 1:3,000 in TBST with 5% BSA. After thorough washing in TBST, bound antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL-Plus; NEN Dupont, Boston, Mass.). Biotinylated molecular weight protein markers were run in the gel and were detected by adding streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase along with secondary antibody.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA from transiently transfected or infected cells was prepared by single-step guanidine extraction as described previously (15). Briefly, cells were lysed on the plate with denaturing solution containing 4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 25 mM sodium citrate, 0.5% Sarkosyl, and 0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol. RNA was isolated from the homogenate by phenol and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction followed by isopropanol precipitation. All RNA preparations were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) at a concentration of 0.1 U/ml for 30 min to remove any residual DNA. RT and subsequent PCR amplification of total cellular RNA were performed with oligonucleotide primers complementary to FeLV-A 61E sequence (GenBank accession no. M18247). The sequence and the location of primers used in this study were as follows: P1, 5′-AACCCAACAGTACCAACAGAT-3′ (7861 to 7881); P2, 5′-AGGATATCTGTGGTTAAGCAC-3′ (8073 to 8093); P3, 5′-AGTCTCAGCAAAGACTTGCGC-3′ (8319 to 8299); and P4, 5′-GGTCTTCCTCGGCGATGAG-3′ (8422 to 8404). First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out with the SuperScript preamplification system for first-strand cDNA kit from GIBCO-BRL with primer P3 or P4. The template cDNAs obtained were amplified with primer P1 or P2. First-strand cDNA synthesis on each sample was also carried out in the absence of reverse transcriptase enzyme to demonstrate that the final PCR products were not derived from contaminating DNA. The PCR mixture was first heated at 94°C for 3 min, and then the following conditions were applied for 30 cycles: denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 90 s. Reactions were finally extended for 5 min at 72°C. Both the RT and the PCR amplification were performed in a PCR Sprint thermal cycler from Hybaid (Franklin, Mass.). PCR products were analyzed on 2% agarose gels followed by staining with ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

FeLV LTRs activate collagenase gene expression.

FeLV-A represents the commonest form of FeLVs that infect domestic cats. Earlier studies indicated that the FeLV LTR has sequence similarities with MuLV LTRs, in particular with respect to certain nuclear protein-binding sites (38, 42, 45, 67). It has been proposed that the U3 region of the FeLV LTR plays a role in the disease pathogenesis similar to that of the MuLV LTR U3 region (30, 32, 48). Studies from our laboratory have shown that the U3 region of Mo-MuLV can transcriptionally upregulate the expression of certain cellular genes (24, 25, 41, 73). We initially wished to determine if the U3 region from the FeLV-A virus has similar transactivation potential. A −517/+62 collagenase-CAT construct was used as the reporter for these studies, because previous reports have demonstrated that the Mo-MuLV and its isolated LTR produce robust transactivation of both the endogenous collagenase IV gene and this reporter construct (24, 73). We first tested collagenase promoter-reporter gene induction by LTRs derived from three different FeLV-A viruses, 61B, 61C, and 61E (61B LTR, 61C LTR, and 61E LTR) (Fig. 2A). CAT activity was induced by 12- to 13-fold in cells cotransfected with collagenase-CAT reporter and any of the three FeLV LTR constructs, in comparison to cells cotransfected with the backbone vector plasmid pTZ19U (the cloning vector for the LTR constructs) as a control. The nucleotide sequence of the LTRs of 61B and 61C differs only minimally from the sequence of 61E LTR. In 61B, nucleotide T at position 109 (with position 1 being the 5′ end of the LTR) is replaced by G, whereas in 61C, nucleotide T at position 109 and G at position 180 are replaced by G and A, respectively (52a). These sequence differences did not affect the ability of these LTRs to activate collagenase gene expression. Although the magnitude of collagenase-CAT induction by Mo-MuLV LTR was slightly but consistently higher than that of induction by the FeLV LTRs, these results clearly show that FeLV LTRs are capable of activation of the collagenase promoter element.

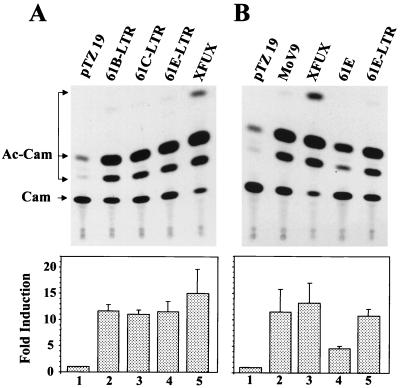

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional activation of a collagenase promoter-reporter by FeLV LTR and full-length FeLV proviral clone. (A) Induction of collagenase promoter by transiently expressed FeLV LTR. One microgram of −517/+62 collagenase-CAT reporter plasmid was cotransfected with 7.5 μg of individual LTR constructs into BALB/3T3 cells by the DEAE-dextran method, as described in Materials and Methods. The Mo-MuLV LTR construct XFUX was used as a positive control. Cotransfection with 7.5 μg of backbone vector plasmid pTZ19U was used to determine the constitutive basal expression of the collagenase promoter-reporter vector. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with PBS and assessed microscopically for green fluorescence under UV light to normalize for transfection efficiency. Cells were harvested, and CAT assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods. Products were separated by thin-layer chromatography. (B) Induction of collagenase promoter-reporter by transient transfection of a full-length FeLV molecular clone. BALB/3T3 cells were cotransfected as described above with either 7.5 μg of FeLV or Mo-MuLV LTR constructs or 10 μg of full-length FeLV or Mo-MuLV proviral clones. These experiments were repeated three times. The thin-layer chromatogram of one representative experiment has been presented. The migration positions of chloramphenicol (Cam) and the acetylated products (Ac-Cam) are indicated. Fold activation for each sample shown at the bottom of each panel was calculated from quantitative data obtained from multiple experiments. Exposed X-ray films were photographed by using AlphaImager 3.4, and densitometric analysis of the image was carried out with the AlphaEase program (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, Calif.). The error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

It was formally possible that the transactivation of promoter-reporter constructs by the FeLV LTRs that we observed would not occur in cells expressing the full-length viral genome. To address this issue, cells were transfected with collagenase-CAT reporter together with full-length proviral clones, and collagenase promoter activity was then assessed (Fig. 2B). Expression of the reporter was fourfold higher in cells transfected with full-length proviral clone 61E than in controls. The magnitude of the induction by the full-length clone was thus consistently 2.5- to 3-fold lower than the induction by the isolated LTR. Interestingly, similarly lower relative levels of transactivation were also observed when the activity of a full-length clone of Mo-MuLV (MoV9) was compared to that of the isolated Mo-MuLV LTR (XFUX) (shown in the left lanes of Fig. 2B). This apparent difference in transactivational activity is likely due rather to the different stoichiometry of LTR/promoter-reporter gene ratios in the two experimental conditions, with a lower relative LTR/reporter gene ratio existing when the whole provirus is transfected. Nevertheless, the significant increase in collagenase-reporter expression observed indicates that collagenase gene expression can be likely upregulated in the presence of the complete viral genome as well as the isolated LTR. Because the feline genome contains many endogenous viral sequences (6, 54, 66), we also tested whether those endogenous FeLVs or their LTRs could transactivate the collagenase promoter. We used the molecularly cloned nearly full-length endogenous CFE-6 and CFE-16 FeLV proviruses (6, 66) in transient-transfection assays with the −517/+62 Coll-CAT reporter. Although these proviral clones each contain two full-length LTRs, neither of these endogenous viruses could activate the collagenase promoter (data not shown), suggesting a lack of transactivational activity in the LTRs of the endogenous (and nonleukemogenic) FeLVs.

Cell lines stably expressing FeLV LTRs activate the collagenase promoter.

To determine whether collagenase promoter activation by the FeLV LTR extends beyond transient expression of the LTR, cell lines containing integrated FeLV LTRs were generated. These cell lines were then tested for their ability to activate the collagenase-CAT promoter. We tested six cell lines (LTR-1 through LTR-6) that were generated by transfecting pCR3.1/61E-LTR-PK plasmid and one generated by transfecting pCR3.1 vector plasmid (vector control) for the presence of a transfected LTR by PCR analysis (data not shown). The reporter plasmid −517/+62 Coll-CAT was then transfected in these cells, and CAT activity was measured 2 days after transfection. A CMV promoter-driven reporter, CMV-Coll-CAT, which expresses CAT activity in all cell lines tested so far, was also separately transfected into all these cell lines to control for any differences in transfectability, and all were found to be equally transfectable (Fig. 3). Cell line LTR-6, which contained a transfected LTR, also activated the collagenase-CAT promoter by a magnitude similar to that induced by transient cotransfection with p61E-LTR [compare LTR(−) to LTR(+) in Fig. 3]. The collagenase promoter was not activated in G418-resistant transfected lines which did not contain the FeLV LTR by PCR (line LTR-1 or vector). Thus, stable expression of the FeLV LTR can also transactivate the collagenase promoter.

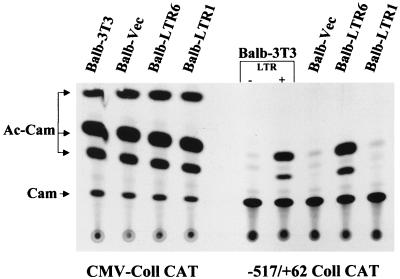

FIG. 3.

Collagenase promoter activation by cell lines stably expressing an FeLV LTR. G418-resistant stable BALB/3T3 cell lines BALB-LTR1, BALB-LTR6, and BALB-vector were transfected with 1.0 μg of −517/+62 collagenase-CAT reporter. Cell lines BALB-LTR1 (later shown to be PCR negative for the LTR) and BALB-LTR6 (later shown to be PCR positive for the LTR) were generated by transfecting BALB/3T3 cells with pCR3.1/61E-LTR-PK followed by G418 selection, whereas cell line BALB-vector was generated by transfecting the empty vector pCR3.1. In addition, normal BALB/3T3 cells were cotransfected with −517/+62 collagenase-CAT reporter and 7.5 μg of either pTZ19 (lane marked with minus sign) or 61E-LTR (lane marked with plus sign) as controls. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, and CAT assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. All these cell lines were also transfected separately with control plasmid CMV-Coll-CAT to compare their transfectability. These experiments were repeated four times. The thin-layer chromatogram of one representative experiment has been presented. The migration positions of chloramphenicol (Cam) and the acetylated products (Ac-Cam) are indicated.

Collagenase gene expression is activated by FeLV LTR in feline cells.

The demonstration of FeLV LTR-mediated transactivation of genes shown above was carried out with BALB cells, which are not a natural host for FeLVs. To determine if the FeLV LTR can transactivate gene expression in the natural setting of virus infection, the feline embryo fibroblast cell line AH927, which supports FeLV infection and replication (57), was employed. Various FeLV LTR constructs and full-length molecular clones were used in cotransfection experiments with the collagenase-CAT reporter construct in AH927 cells (Fig. 4). CAT activity was 4.5- to 5.1-fold higher in AH927 cells transfected with the LTR constructs (61B-LTR, 61C-LTR, and 61E-LTR) and 4.2-fold higher in cells transfected with the full-length clone 61E than in control transfections. Another FeLV LTR construct, 61E-P15E/LTR, also enhanced CAT expression by 5.2-fold. These data suggest that collagenase gene expression may be regulated as a result of FeLV infection and that the LTR sequences alone are sufficient for this effect. It should be noted that the LTR sequences for construct 61E-P15E/LTR came from the 3′ LTR of the virus, whereas the LTRs in the other vectors were all derived from the 5′ LTR. This finding indicates that both the 5′ and 3′ LTRs can transactivate collagenase gene expression.

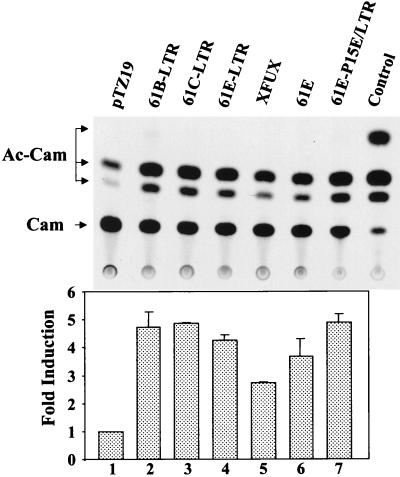

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional activation of collagenase promoter-reporter by various FeLV LTR and full-length FeLV clones in the feline embryo fibroblast cell line AH927. Cotransfection experiments were carried out as described in the legend to Fig. 2, except that 0.5 μg of collagenase-CAT reporter was used for each plate and cells were treated with DEAE-dextran–DNA complex for only 3 h. For the full-length proviral clone, 10 μg of plasmid per plate was used, and for the LTR and backbone vector, 7.5 μg of plasmid per plate was used. In one plate, cells were also transfected with 1 μg of CMV-Coll-CAT construct alone (the control lane) to assess transfection efficiency in these cells compared to that in other cell lines. Forty-eight hours after transfection, CAT assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. An autoradiogram of a plate from a representative experiment is shown. The migration positions of chloramphenicol (Cam) and the acetylated products (Ac-Cam) are indicated. Fold induction calculations were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the means.

FeLV LTR transactivates MCP-1 and MHC class I gene expression.

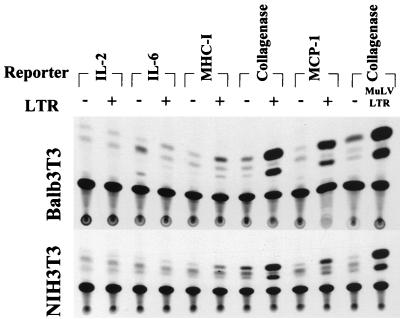

We next determined if FeLV LTR could activate the expression of other cellular genes that are known to influence proliferation of hematopoietic cells or which are activated in various malignancies. CAT reporter constructs driven by promoter regions derived from the IL-2, MHC class I antigen, MCP-1, and IL-6 genes were employed in transient-cotransfection experiments with the FeLV LTR construct 61E-LTR. Cotransfections were performed in two different cell lines, BALB/3T3 and NIH 3T3. Figure 5 shows CAT activities in cells transfected with various CAT constructs plus LTRs or control vector plasmids. In BALB/3T3 cells, the collagenase promoter-reporter expression was activated by the LTRs, as reported above. In addition, expression of the MCP-1 and MHC class I promoter-reporter was also induced by the FeLV LTR-containing vectors. The level of activation of the MHC class I genes was consistently much lower than what we had observed with the Mo-MuLV LTR, however. No transactivation of other promoter-reporter vectors was observed, demonstrating that transactivation by the FeLV LTR has specificity in terms of the responsive genes, just as has been reported for murine retroviral LTRs (24, 25, 41). Similar patterns of gene activation were seen with NIH 3T3 cells. Mo-MuLV LTR-mediated activation of the collagenase promoter was used as a positive experimental control in these studies.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of transcriptional activation of promoters of various genes by FeLV LTR. Transient-cotransfection experiments were performed with either BALB/3T3 or NIH 3T3 cells as described in Materials and Methods, with p61E-LTR and CAT reporters driven by the promoter regions of various genes known to be important for cell growth or inflammation, plus an internal transfection control plasmid. Seven and one-half micrograms of pTZ19U (−) or p61E-LTR (+) plasmid was cotransfected with 7.5 μg of IL-2 (−585 IL-2-CAT), 7.5 μg of IL-6 (−225 IL-6-CAT) or MHC class I (KbHN-CAT), 1 μg of collagenase (−517/+62 Coll-CAT), or 4 μg of MCP-1 (−543 JE-CAT) reporter constructs. Collagenase gene induction by the Mo-MuLV LTR was used as control. Vector control for the Mo-MuLV LTR was 7.5 μg of pBR322 plasmid. Forty-eight hours after transfection, CAT assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. One representative autoradiogram for each cell line is shown. Experiments for both cell types were repeated three times with identical results.

FeLV LTR induces AP-1 DNA-binding activity.

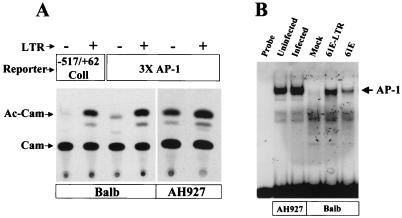

Earlier studies of the Mo-MuLV LTR from our laboratory have shown that some of the cellular genes that are upregulated by MuLV have AP-1 DNA-binding sites in their promoter regions and that this AP-1 site is both necessary and sufficient for induction by the LTR (73). Because of the finding reported above that the FeLV LTR can transactivate the collagenase gene promoter, the activity of which is known to be regulated by AP-1, we next tested whether AP-1 activity is modulated by the FeLV LTR. We addressed this issue by measuring both AP-1 DNA-binding activity and AP-1-dependent transcriptional activity. A CAT reporter construct containing three tandem AP-1 consensus DNA-binding sites (3×AP-1-CAT) was used in transient-cotransfection experiments with FeLV LTRs. In addition, the DNA binding of nuclear protein extracts from FeLV-infected or -transfected cells to a labeled oligonucleotide encoding an AP-1 site was quantitated in EMSAs. The FeLV LTR construct 61E-LTR activated CAT expression from the 3×AP-1-CAT vector in both BALB/3T3 and AH927 cells (7.4- and 2.1-fold, respectively) (Fig. 6A). EMSA results from FeLV-infected AH927 and LTR-transfected BALB/3T3 cells demonstrated parallel increases in AP-1 DNA-binding activity (Fig. 6B). The DNA-binding activity of AP-1 was increased 10.6-fold in cells transfected with full-length virus 61E and 26.8-fold with the isolated LTR. AP-1 DNA-binding activity was also increased 1.5-fold in infected feline AH927 cells over that in uninfected cells. The basal AP-1 DNA-binding activity in the AH927 cells was, however, relatively high. These results collectively suggest that AP-1 activity is induced by FeLV infection and that the presence of the LTR alone can account for this induction.

FIG. 6.

Activation of the AP-1 complex by the FeLV LTR. (A) Transcriptional activation of a CAT reporter with 3×AP-1-binding-site-containing promoter element by the LTR. BALB/3T3 or AH927 cells were cotransfected with 3×AP-1-CAT and p61E-LTR(+) or vector pTZ19U(−) as detailed in the legends to Fig. 2 and 3. A transcriptional activation assay of the collagenase IV promoter by p61E-LTR(+) or vector pTZ19U(−) was also performed in the same set of experiments. Forty-eight hours after transfection, CAT assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The migration positions of chloramphenicol (Cam) and the acetylated products (Ac-Cam) are indicated. (B) EMSAs with an oligonucleotide containing an AP-1-binding site. Nuclear extracts from cells were incubated with a radiolabeled double-stranded AP-1 consensus oligonucleotide probe as described in Materials and Methods, and DNA-protein complexes were separated on a 5% polyacrylamide gel. Before preparation of nuclear extracts, all cells were starved overnight in DMEM containing 0.5% appropriate serum. Extracts in lanes marked “61E-LTR” and “61E” came from transiently transfected BALB/3T3 cells 40 h after transfection. The lane marked “Mock” refers to normal BALB/3T3 cells. “Uninfected” and “Infected” AH927 cells refer to normal AH927 cells and AH927 cells that were transfected with full-length FeLV-A proviral clone p61E 3 months previously, respectively. Production of FeLV by this cell line has been confirmed with the Viracheck enzyme immunoassay kit (Synbiotics, Inc., San Diego, Calif.) for FeLV core protein antigen p27. The migration position of the DNA–AP-1 complex is indicated.

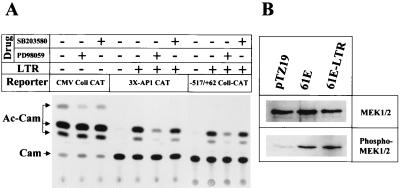

Inhibition of MEK1 and -2 activity interferes with FeLV LTR-mediated gene transactivation.

AP-1 activity in cells can be altered by mechanisms that either increase the abundance of its protein components or modify their activity (40). Weng et al. have shown that the increase in AP-1 activity during Mo-MuLV infection, or by the Mo-MuLV LTR, is accompanied by an increase in c-Jun, but this increase could be the result of AP-1 activation rather than the cause, as c-jun is an AP-1-inducible gene (73). Mitogen-activated protein kinases play an important role in the regulation of AP-1 activity (40). Three different MAPKs (the ERKs, the JNKs, and the FRKs) are known to mediate the induction of AP-1 activity. To determine if FeLV LTR-mediated activation of AP-1 activity is the consequence of activation of any of those MAPK pathways, we utilized the flavone compound PD98059 and the pyridinyl imidazole SB203580, which are specific inhibitors of the Raf-1/MAPK and P38/SAPK pathways, respectively (17). At 50 μM concentrations, PD98059 specifically inhibits phosphorylation of MEK1 and MEK2 (1). SB203580, at 10 μM concentrations, inhibits both p38MAPK and SAPK pathways (19). BALB/3T3 cells were cotransfected with the 3×AP-1-CAT construct and the LTR expression plasmid 61E-LTR and then maintained in normal growth medium containing either 50 μM PD98059 or 10 μM SB203580. Twenty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed and processed for CAT assay. In the presence of PD98059, FeLV LTR-mediated transcriptional activation of the 3×AP-1-CAT reporter was decreased by 5.3-fold (Fig. 7A). In contrast, treatment with SB203580 did not alter the level of activation of the 3×AP-1-CAT reporter by the LTR. To control for any potential toxic or inhibitory effects of these drugs on cellular function or transfection, BALB/3T3 cells were transfected with a CMV-driven reporter (CMV-Coll-CAT) and treated with the drugs in a similar fashion, and CAT activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 7A, exposure to the drugs did not affect CAT expression driven by the CMV enhancer. Our results thus demonstrate that PD98059 interferes with FeLV LTR-mediated activation of AP-1, and activation of MEK1 and -2 may thus be an intermediate step in the transactivation process.

FIG. 7.

Effect of expression of the FeLV LTR on MAP kinase signal transduction pathways. (A) Action of MAP kinase-specific inhibitors PD98059 and SB203580 on transcriptional activation of 3×AP-1-binding-site-containing promoter and −517/+62 Coll-CAT reporter by FeLV LTR. The LTR expression plasmid p61E-LTR was cotransfected with either 3×AP-1-CAT reporter or −517/+62 Coll-CAT reporter. As a control, pTZ19U vector was also cotransfected with the above two reporters. In another set of experiments, BALB/3T3 cells were transfected with CMV-Coll-CAT reporter, as described in Materials and Methods. PD98059 and SB203580 (50 and 10 μM final concentrations, respectively) were added to the medium immediately after the chloroquine treatment step. Twenty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested for CAT assays as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The migration positions of chloramphenicol (Cam) and the acetylated products (Ac-Cam) are indicated. This experiment was repeated twice with identical results. (B) Effect of expression of the FeLV LTR or full-length FeLV on phosphorylation of the Raf-MAPK pathway intermediates MEK1 and -2. BALB/3T3 cells were transiently transfected with vector pTZ19U, full-length clone p61E, or LTR clone p61E-LTR by the Lipofectamine Plus transfection method. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was changed to DMEM with 0.5% DCS, and incubation was continued for another 24 h. Total cell lysates were then prepared, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Twenty micrograms of protein from each cell lysate was separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel in duplicate and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Total MEK1 and -2 protein and phosphorylated MEK1 and -2 protein on the membrane were detected by immunoblotting with pan-anti-MEK1 and -2 serum or phosphospecific anti-MEK1 and -2 serum (New England Biolabs) as described in Materials and Methods.

To determine if FeLV LTR-induced MEK1 and -2 activity is required for transactivation of the collagenase gene, as it is for the 3×AP-1-CAT construct, we used the same inhibitors in cotransfection assays with the −517/+62 collagenase-CAT reporter and the p61E-LTR. Whereas PD98059 reduced FeLV LTR-mediated collagenase gene induction by 5.5-fold, SB203580 had no effect. Thus, transactivation of the AP-1-inducible gene collagenase and that of the chimeric 3×AP-1-CAT construct by the FeLV LTR are both dependent upon MEK1 and -2 activity.

MEK1 and -2 activation is achieved by phosphorylation of two serine residues at positions 217 and 221 (1). Anti-MEK1 and -2 and phosphospecific anti-MEK1 and -2 sera were used in immunoblotting to determine the level of phosphorylated MEK1 and -2 in BALB/3T3 cells transfected with the FeLV LTR or the full-length FeLV proviral clone (Fig. 7B). BALB/3T3 cells transfected with vector pTZ19U served as a control. Both LTR-transfected and full-length provirus-transfected cells showed higher levels of phosphorylated MEK1 and -2 than did control vector-transfected cells (Fig. 7B). The levels of total MEK1 and -2 remained the same in all three cells. FeLV LTR expression, therefore, induced MEK1 and -2 phosphorylation.

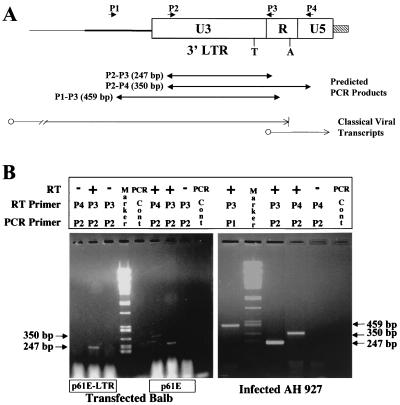

U3 region of FeLV LTR generates an RNA transcript.

Previous studies with Mo-MuLV have shown that cellular gene transactivation by the LTR is dependent on its ability to generate a polymerase III-directed RNA transcript encoded by the U3 region (12, 13). The sequences of the FeLV LTRs used in these studies, when examined for potential open reading frames, do not appear to encode a protein. Furthermore, we have also observed that FeLV-mediated transcriptional activation of the collagenase gene is independent of the orientation of the LTR in an expression vector (30a). We therefore investigated the possibility that the FeLV LTR could generate an RNA transcript from the U3 region, in a manner analogous to that of the MuLV LTR. An RT-PCR technique designed to specifically detect U3 transcripts generated from the LTR was employed. The experimental strategy is depicted in Fig. 8A. Total cellular RNA (DNase treated) from transfected or infected cells was first reverse transcribed with primer P3 or P4, which is complementary to the 61E-LTR sequence. Individual reaction products were then PCR amplified with plus-strand primer P1 or P2 (Fig. 8B). RNA extracted from BALB/3T3 cells transfected with the 61E-LTR was subjected to RT with primer P3 (complementary to nucleotides 8299 to 8319). Subsequent PCR amplification of the product with primer P2 generated a 247-bp product. When first-strand cDNA synthesis on the same sample was carried out with the P3 or P4 primer (complementary to nucleotides 8404 to 8422) in the absence of reverse transcriptase enzyme and then PCR amplified with the P2 primer, no product was produced (data not shown). This suggests that the 247-bp PCR product was derived from an RNA transcript generated by the LTR. RNA extracted from BALB/3T3 cells transfected with the entire p61E FeLV provirus, when subjected to RT with primer P3 and amplification with primer P2, also generated a 247-bp product. RT and PCR amplification of RNA from cells infected with FeLV, or from cells transfected with full-length virus, with this primer pair, however, would also amplify the major proviral transcript, which initiates in the R region (Fig. 8A). In order to detect LTR-specific transcripts in the presence of the whole viral genome, a different strategy was employed. Primer P4, which is complementary to U5 sequences, was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis. When this protocol was performed on RNA samples from BALB/3T3 cells transfected with full-length clone 61E, a 350-bp product was generated. Such a product from the P2-P4 primer pair cannot be generated from the major viral transcript. First-strand cDNA synthesis with the P3 primer in the absence of reverse transcriptase, followed by PCR amplification with P2 primer, did not, however, yield any product. These results indicated that LTR-specific RNA transcripts are generated in cells transfected with LTR alone or with full-length virus.

FIG. 8.

RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from cells expressing FeLV or the FeLV LTR. (A) Schematic diagram of the oligonucleotide primers and their locations on the viral genome. The origin and termination of the classical viral genomic transcripts are shown by thin lines. T, TATA box of classical genomic promoter; A, polyadenylation signal sequence. Predicted PCR products with various primer pair combinations and their sizes are also indicated. (B) (Right) RT-PCR with DNase-treated RNA isolated from BALB/3T3 cells transfected with either p61E-LTR or full-length virus 61E. (Left) RT-PCR with DNase-treated RNA isolated from FeLV 61E-infected AH927 cells. The origin of the infected AH927 cells has been described in the legend to Fig. 5. “PCR Cont” refers to an amplification product with all the primers and all other components of PCRs including Taq polymerase but no RNA or DNA template. This was done to test for contamination of the reagents used in the PCR. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels. PstI-cut lambda DNA was used as a marker in the gel. The migration positions and sizes of the amplified products are indicated.

AH927 cells infected with FeLV 61E were also tested for LTR-specific transcripts. Total cellular RNA was extracted from those cells, treated with DNase, and subjected to RT and PCR amplification as described above. Results presented in the right panel of Fig. 8B demonstrate that first-strand cDNA synthesis with primer P3, and PCR amplification with primer P1 or P2, resulted in products of 459 and 247 bp in size, respectively. Again, first-strand cDNA synthesis with P4 and PCR amplification with P2 resulted in a product of 350 bp. Whereas the P1-P3 and P2-P3 products could be generated from the major viral transcript, the observed P2-P4 product can come only from LTR-specific transcripts. Primer pair P2-P4 did not yield any product when reverse transcriptase was not used during first-strand cDNA synthesis, demonstrating that these products are not the result of DNA contamination of the RNA preparations. Thus, LTR-specific transcripts are generated in FeLV-infected AH927 cells. Because AH927 cells are of feline origin and are known to contain endogenous FeLV LTR sequences, we also examined whether endogenous FeLV LTR-specific RNA transcripts are generated in these cells. An RT primer to the homologous R region (P3) was used along with two independent endogenous LTR-specific primers to amplify any putative RNA transcript from an endogenous retroviral LTR in uninfected AH927 cells. The same primers were used to detect endogenous retroviral LTR sequences in cellular genomic DNA. The results demonstrated that, although genomic DNA from AH927 cells does possess endogenous LTR sequences, LTR-specific transcripts are not generated (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that transient or stable expression of the Mo-MuLV LTR in murine fibroblasts or in human T-cell lines can upregulate expression of specific cellular genes encoding such proteins as MHC class I antigen, T-cell activation antigens (such as CD2, CD3, CD4, and T-cell receptor β), the cytokine MCP-1, and collagenase IV (matrix metalloproteinase 9) (24–26, 41, 74). Expression of these genes is tightly controlled during normal cellular growth and development. We hypothesized that the transcriptional activation of these genes by Mo-MuLV LTR could play a role in the process of tumorigenesis induced by these viruses. FeLVs induce various malignant diseases in cats, which are similar to the diseases induced by MuLVs in mice. The basic genomic organizations of both of these viruses are very similar, and neither contains an oncogene. We wished to determine in this study whether the LTR from FeLV would similarly induce cellular gene activation. We show here that transient or stable expression of the FeLV LTR can induce transcription of the collagenase IV gene in murine fibroblasts as well as in feline embryo fibroblasts. Furthermore, we have shown that this transactivation occurs in cells, which express full-length viruses, as well as in isolated LTRs, suggesting that other viral components do not interfere with the transcriptional activation ability of the LTR. These findings demonstrate that the LTRs from oncogene-deficient retroviruses other than Mo-MuLV can also enhance cellular gene expression.

Several earlier studies have established that the LTRs of MuLVs and FeLVs are important determinants for both tissue tropism (8, 9, 31, 67) and their pathogenic potential (11, 21, 30, 42, 45). These studies have shown that the LTRs exert their actions by binding transcriptional activator proteins in a tissue-specific manner, thereby enhancing virus expression. Duplication of this enhancer region in the LTR is another event that was found to be closely related to leukemogenesis in some analyses. Analysis of LTR sequence data from naturally occurring and artificially induced tumors in mice, and mutational analysis of the protein-binding sites in the LTRs, have supported these mechanisms for the role of the LTR in leukemogenesis (48, 58). There are, however, also reports suggesting that these activities or modifications of the LTR do not necessarily match with the pathogenic potential of a given strain. Recently, Dai et al. (20), in their work on Friend MuLV, have shown that the strength of the transcriptional activity of the enhancer element of the LTR from the weakly leukemogenic strain FIS-2 was equal to, or higher than, that from the highly leukemogenic parental stain cl.57. This lack of correlation was noted in animal studies by in situ hybridization and in CAT reporter assays, with multiple cell lines. In another study, Rohn and Overbaugh (58), through study of sequence variation in tumors developing in cats following inoculation with a molecularly cloned virus, showed that, although duplication of the enhancer region is a common occurrence, it was not a necessity for leukemogenesis. Earlier studies on lymphomas induced by inoculation of polytropic MuLV into AKR mice indicated that the activation of uncharacterized cellular genes may be important in inducing a preleukemic proliferative stage of disease (52). Following this polyclonal hyperplasia, activation of a proto-oncogene in a subset of cells within this proliferating population occurs, perhaps by means of a viral promoter integration event, finally conferring full malignancy. Although site-specific integration of both MuLV and FeLV around similar loci such as c-myc, pim-1, and flvi-2/bmi-1 has been documented in many MuLV and FeLV tumor specimens (43, 44, 49, 62), such an event does not appear to be mandatory for tumor development, however. For example, in a recent study in which recombinant Mo-MuLV containing U3 sequences from FeLV was used to infect neonatal mice, activation of specific proto-oncogenes often found to be activated in Mo-MuLV- or FeLV-induced tumors was not observed in the tumors which developed (68). Taken together, these studies indicate that alternative virus-driven mechanisms may be important in leukemogenesis induced by oncogene-deficient retroviruses. The products of the genes that we show here to be transactivated by the FeLV LTR, namely, collagenase, MCP-1, and MHC class I antigens, have all been implicated in cancer promotion and spread (23, 27, 33, 35, 46, 50, 72). Our previous finding that Mo-MuLV LTR can activate transcription of cellular genes and this present report of the ability of FeLV-LTR to do so also thus suggest a potential mechanism in which the LTRs from these viruses contribute to the multistep leukemogenic process through trans regulation of cellular genes. Studies are under way to determine if specific mutations in the FeLV genome which interfere with the ability of the FeLV LTR to generate an RNA transcript and augment cellular gene transcription will impair their capacity for leukemogenesis.

Although we have convincingly demonstrated that the FeLV LTR, specifically the U3 region, transactivates certain cellular genes, the molecular mechanism by which it does so remains as yet incompletely defined. The smallest region of the LTR shown to be sufficient for this transactivation of cellular genes is unlikely to produce any functional protein, for a number of reasons. The longest reading frame present in this region would encode only 32 amino acids and contains no translation termination sequence. Furthermore, we have observed that the transactivational activity of the U3 region of the FeLV LTR is independent of its orientation in an expression vector plasmid (30a), and, thus, any potential contribution of the 32-amino-acid open reading frame is not likely to be relevant. We have shown herein that U3 region-specific RNA transcripts are generated in cells expressing exogenous FeLV LTRs. Further, the inability of the endogenous feline retroviral LTRs to make such a transcript suggests a necessary role of this transcript in gene transactivation by the virus. In related studies with the Mo-MuLV LTR (13), we observed that such transactivation was dependent upon the ability of the LTR to code for a similar RNA transcript, likely the product of RNA polymerase III. Our findings in the present study are thus consistent with our hypothesis that oncogene-deficient retroviruses activate cellular host gene transcription through an LTR-RNA transcript.

The AP-1 complex is a well-known modulator of collagenase IV gene expression (3). We show herein that the DNA-binding activity of the AP-1 complex is increased in cells that are expressing an FeLV LTR. It is thus possible that the FeLV-mediated induction of collagenase IV gene expression is the result of the activation of AP-1 DNA-binding activity. However, the promoter element of the collagenase gene used in our collagenase-CAT reporter construct also contains other elements, the activation of which could also lead to higher expression of the promoter. It was therefore possible that FeLV LTR-mediated activation of collagenase IV gene expression was mediated through those other elements. Our results with the 3×AP-1-CAT reporter demonstrated that the transcriptional activation activity of the AP-1 complex is markedly increased during FeLV LTR expression. We have previously shown that mutations of the AP-1 site at the −67 position of the collagenase IV promoter in the collagenase-CAT reporter, which abrogate AP-1 binding, prevent transactivation by the Mo-MuLV LTR (73). These findings together suggested more directly a necessary and sufficient role of the AP-1-binding site in collagenase IV gene induction by retroviral LTRs.

AP-1 is a master transcriptional activation complex that integrates signals from diverse stimuli. AP-1 is known to transcriptionally activate numerous genes that lead to activation, proliferation, and transformation or that confer protection from apoptosis. Several levels of regulation of AP-1 activity are known, including the intracellular levels of the protein components Jun and Fos and phosphorylation or dephosphorylation of these protein components at specific sites (5, 10, 37, 59). Our earlier studies of Mo-MuLV have shown that c-Jun expression is increased upon expression of LTR (73). Because c-jun itself is an AP-1-inducible gene, it was not possible to determine directly from these studies whether this induction was the result of, or the cause of, AP-1 activation. It was further shown that the protein kinase C inhibitor staurosporine could abrogate LTR-induced DNA-binding activity of the AP-1 complex, suggesting involvement of protein kinase C in the process. Our studies with MAPK inhibitors suggest a mechanism through which AP-1 can be activated by FeLV LTRs. The compounds PD98059 and SB203580 used in this study are known to be specific inhibitors of the Raf-1/MAPK and the p38/SAPK pathways, respectively (1, 17, 19). FeLV LTR-mediated activation of AP-1 was unaffected by the p38/SAPK pathway inhibitor, whereas the Raf-1/MAPK pathway inhibitor markedly suppressed LTR-inducible AP-1 transcriptional activating activity. PD98059, at a concentration of 10 μM, specifically inhibits phosphorylation of MEK1 at positions 217 and 221 by upstream kinases such as Raf-1, although it does not interfere with the function of phosphorylated MEK1 (1). At a higher concentration of the drug (50 μM), however, MEK2 phosphorylation is also inhibited. Since we used only a 50 μM concentration of PD98059, we cannot ascertain if the blockade of LTR-mediated activation by AP-1 was due to MEK1, to MEK2 inactivation, or both. Immunoblotting studies with phosphospecific MEK1 and -2 antibodies confirmed that the level of phosphorylated MEK1 and -2 was much higher in LTR-expressing cells than in normal control cells. SB203580 selectively inhibits SAPK isoform 2 (SAPK2/p38) (18, 19). Although it binds to a generic ATP pocket, this drug does not interfere with related kinases, such as MAPK1/ERK1, MAPK2/ERK2, SAPK1c/JNK1, SAPK3/ERK6, and SAPK4 (7, 18, 19, 36, 70). Based on these and previously reported findings, several hypotheses can be advanced as to how AP-1 activation by the LTR is mediated. Our previous work indicated that transcriptional activation of the components of the AP-1 complex could augment AP-1 activation (73). Indeed, increases in the levels of the AP-1 protein components alone can result in increased AP-1 activity (37, 40). Phosphorylated MEK1 can induce c-fos transcription through the serum response element by activating MAPK/ERK1 and -2 and subsequent phosphorylation of TCF. There are additional regulatory sites in the c-fos promoter that could potentially also be targets of the LTR through activation of MEK1, including the cyclic AMP response element. One downstream kinase in the MEK1/MAPK pathway, MAPKAP-K1, can phosphorylate cyclic AMP response element-binding protein. Another member of these MAPKAP kinases, MAPKAP-K2, which is activated by SAPK2/p38, can also phosphorylate cyclic AMP response element-binding protein, although inhibition of its activating kinase (inhibition of SAPK2/p38 by SB203580) does not inhibit AP-1 activation by the LTR. Furthermore, we have not found increases in c-fos transcripts in cells expressing the Mo-MuLV LTR (73). Activated MEK1 can also induce c-Jun expression through pathways that involve cross-talk between MAPK pathways. For example, Pulverer et al. have shown (55) that the p42/44 MAPK, which is a substrate of MEK1, can phosphorylate two serine residues in the amino-terminal A1 transactivation domain of c-Jun and thereby indirectly induce its own synthesis. Furthermore, Franklin and Kraft (29) have shown that constitutively activated MEK1 can stimulate MAPK and SAPK activity, as well as AP-1-, serum response element-, and c-Jun-mediated transcriptional activity, in U937 cells. Therefore, FeLV LTR-mediated phosphorylation of MEK1 and -2 alone could explain the elevations in AP-1 activity observed in LTR-expressing cells. The identical pattern of action of PD98059 and lack of activity of SB203580 on collagenase IV gene induction by the FeLV LTR as on AP-1-CAT induction by the FeLV LTR supports the hypothesis that MEK1 and -2 activation of AP-1 by the LTR mediates both processes.

Not all host cellular gene transactivation by the LTR is likely to be mediated through AP-1, however. We show in the present study that, in addition to the collagenase IV gene, the MCP-1 and MHC class I genes are also induced to different degrees by the FeLV LTR. Our previous studies demonstrated that the Mo-MuLV LTR also induces these same genes (14, 25, 74). Although the MCP-1 promoter contains two potential 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response elements (the consensus AP-1-binding sequences), AP-1 activation does not appear to be responsible for its LTR-mediated induction (25). Similarly, the MHC class I promoter element that we found to be activated by Mo-MuLV LTR did not have an AP-1-binding site and is not regulated by AP-1 (14). These findings strongly suggest that other upstream elements and binding factors may have a regulatory role in LTR-mediated gene activation.

We conclude from our studies that expression of the FeLV LTR alone can induce specific cellular gene expression through activation of MAP kinase pathways leading to activation of AP-1. It is possible that, by means of induction of specific genes involved in cell growth and development and in inflammation, the LTRs of Mo-MuLV and FeLV contribute to the preleukemic state of hematopoietic hyperplasia and splenomegaly seen in Mo-MuLV- or FeLV-mediated leukemia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Julie Overbaugh, Pradip Roy-Burman, Brian Seed, Peter Angel, A. J. van der Eb, P. B. Sehgal, Ellen Rothenberg, and Michael Karin for their generous gifts of cell lines or plasmids.

This work was supported in part by grant P60AR20613 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and by grant CA50459 from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi D R, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley D T, Saltiel A R. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27489–27494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.46.27489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews N C, Faller D V. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2499. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angel P, Baumann I, Stein B, Delius H, Rahmsdorf H J, Herrlich P. 12-O-Tetradecanoyl-phorbol-13-acetate induction of the human collagenase gene is mediated by an inducible enhancer element located in the 5′-flanking region. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2256–2266. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.6.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angel P, Hattori K, Smeal T, Karin M. The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell. 1988;55:875–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angel P, Karin M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1072:129–157. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(91)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry B T, Ghosh A K, Kumar D V, Spodick D A, Roy-Burman P. Structure and function of endogenous feline leukemia virus long terminal repeats and adjoining regions. J Virol. 1988;62:3631–3641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.10.3631-3641.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyaert R, Cuenda A, Vanden Berghe W, Plaisance S, Lee J C, Haegeman G, Cohen P, Fiers W. The p38/RK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulates interleukin-6 synthesis response to tumor necrosis factor. EMBO J. 1996;15:1914–1923. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boral A L, Okenquist S A, Lenz J. Identification of the SL3-3 virus enhancer core as a T-lymphoma cell-specific element. J Virol. 1989;63:76–78. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.76-84.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bösze Z, Thiesen H-J, Charnay P. A transcriptional enhancer with specificity for erythroid cells is located in the long terminal repeat of the Friend murine leukemia virus. EMBO J. 1986;5:1615–1623. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyle W J, Smeal T, Defize L H, Angel P, Woodgett J R, Karin M, Hunter T. Activation of protein kinase C decreases phosphorylation of c-Jun at sites that negatively regulate its DNA-binding activity. Cell. 1991;64:573–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90241-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatis P A, Holland C A, Silver J E, Frederickson T N, Hopkins N, Hartley J W. A 3′ end fragment encompassing the transcriptional enhancers of nondefective Friend virus confers erythroleukemogenicity on Moloney leukemia virus. J Virol. 1984;52:248–254. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.248-254.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi S Y, Faller D V. The long terminal repeats of a murine retrovirus encode a trans-activator for cellular genes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19691–19694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi S-Y, Faller D V. A transcript from the long terminal repeats of a murine retrovirus associated with trans activation of cellular genes. J Virol. 1995;69:7054–7060. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7054-7060.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi S Y, van de Mark K, Faller D V. Identification of a cis-acting element in the class I major histocompatibility complex gene promoter responsive to activation by retroviral sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:965–970. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.965-970.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chumakov I, Stuhlmann H, Harbers K, Jaenisch R. Cloning of two genetically transmitted Moloney leukemia proviral genomes: correlation between biological activity of the cloned DNA and viral genome activation in the animal. J Virol. 1982;42:1088–1098. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.3.1088-1098.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen P. The search for physiological substrates of MAP and SAP kinases in mammalian cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:353–361. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuenda A, Cohen P, Buee-Scherrer V, Goedert M. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase-3 (SAPK3) by cytokines and cellular stresses is mediated via SAPKK3 (MKK6); comparison of the specificities of SAPK3 and SAPK2 (RK/p38) EMBO J. 1997;16:295–305. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza Y N, Meier R, Cohen P, Gallagher T F, Young P R, Lee J C. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai H Y, Troseth G I, Gunleksrud M, Bruland T, Solberg L A, Aarset H, Kristiansen L I, Dalen A. Identification of genetic determinants responsible for the rapid immunosuppressive activity and the low leukemogenic potential of a variant of Friend leukemia virus, FIS-2. J Virol. 1998;72:1244–1251. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1244-1251.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DesGroseillers L, Jolicoeur P. The tandem direct repeats within the long terminal repeat of murine leukemia viruses are the primary determinant of their leukemogenic potential. J Virol. 1984;52:945–952. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.3.945-952.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donahue P R, Hoover E A, Beltz G A, Riedel N, Hirsch V M, Overbaugh J, Mullins J I. Strong sequence conservation among horizontally transmissible, minimally pathogenic feline leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1988;62:722–731. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.3.722-731.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faller D V. Modulation of MHC antigen expression by retroviruses. In: Blair G E, Maudsley D J, Pringle C R, editors. MHC antigen expression and disease. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 150–191. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faller D V, Weng H, Choi S Y. Activation of collagenase IV gene expression and enzymatic activity by the Moloney murine leukemia virus long terminal repeat. Virology. 1997;227:331–342. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faller D V, Weng H, Graves D T, Choi S Y. Moloney murine leukemia virus long terminal repeat activates monocyte chemotactic protein-1 protein expression and chemotactic activity. J Cell Physiol. 1997;172:240–252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199708)172:2<240::AID-JCP11>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faller D V, Wilson L D, Flyer D C. Mechanism of induction of class I major histocompatibility antigen expression by murine leukemia virus. J Cell Biochem. 1988;36:297–309. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240360310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Festenstein H, Garrido F. MHC antigens and malignancy. Nature. 1986;322:502–503. doi: 10.1038/322502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flyer D C, Burakoff S J, Faller D V. Retrovirus-induced changes in major histocompatibility complex antigen expression influence susceptibility to lysis by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1985;135:2287–2292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franklin C C, Kraft A S. Constitutively active MAP kinase kinase (MEK1) stimulates SAP kinase and c-Jun transcriptional activity in U937 human leukemic cells. Oncogene. 1995;11:2365–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fulton R, Plumb M, Shield L, Neil J C. Structural diversity and nuclear protein binding sites in the long terminal repeats of feline leukemia virus. J Virol. 1990;64:1675–1682. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1675-1682.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Ghosh, S. K., and D. V. Faller. Unpublished observation.

- 31.Golemis E, Li Y, Fredrickson T N, Hartley J W, Hopkins N. Distinct segments within the enhancer region collaborate to specify the type of leukemia induced by nondefective Friend and Moloney viruses. J Virol. 1989;63:328–337. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.1.328-337.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golemis E A, Speck N A, Hopkins N. Alignment of U3 region sequences of mammalian type C viruses: identification of highly conserved motifs and implications for enhancer design. J Virol. 1990;64:534–542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.534-542.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodenow R S, Vogel J M, Linsk R L. Histocompatibility antigens on murine tumors. Science. 1985;230:777–783. doi: 10.1126/science.2997918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorman C M, Moffat L F, Howard B H. Recombinant genomes which express chloramphenicol acetyltransferase in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:1044–1051. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.9.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graves D T, Jiang Y L, Williamson M J, Valente A J. Identification of monocyte chemotactic activity produced by malignant cells. Science. 1989;245:1490–1493. doi: 10.1126/science.2781291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hazzalin C A, Cano E, Cuenda A, Barratt M J, Cohen P, Mahadevan L C. p38/RK is essential for stress-induced nuclear responses: JNK/SAPKs and c-Jun/ATF-2 phosphorylation are insufficient. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1028–1031. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunter T, Karin M. The regulation of transcription by phosphorylation. Cell. 1992;70:375–387. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishimoto A, Takimoto M, Adachi A, Kakuyama M, Kato S, Kakimi K, Fukuoka K, Ogiu T, Matsuyama M. Sequences responsible for erythroid and lymphoid leukemia in the long terminal repeats of Friend-mink cell focus-forming and Moloney murine leukemia viruses. J Virol. 1987;61:1861–1866. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.6.1861-1866.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarrett O, Russell P H. Differential growth and transmission in cats of feline leukaemia viruses of subgroups A and B. Int J Cancer. 1978;21:466–472. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910210411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koka P, van de Mark K, Faller D V. trans-Activation of genes encoding activation-associated human T lymphocyte surface proteins by murine retroviral sequences. J Immunol. 1991;146:2417–2425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenz J, Celander D, Crowther R L, Patarca R, Perkins D W, Haseltine W A. Determination of the leukemogenicity of a murine retrovirus by sequences within the long terminal repeat. Nature. 1984;308:467–470. doi: 10.1038/308467a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levesque K S, Bonham L, Levy L S. flvi-1, a common integration domain of feline leukemia virus in naturally occurring lymphomas of a particular type. J Virol. 1990;64:3455–3462. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3455-3462.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy L S, Lobelle-Rich P A, Overbaugh J. flvi-2, a target of retroviral insertional mutagenesis in feline thymic lymphosarcomas, encodes bmi-1. Oncogene. 1993;8:1833–1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Golemis E, Hartley J W, Hopkins N. Disease specificity of nondefective Friend and Moloney murine leukemia viruses is controlled by a small number of nucleotides. J Virol. 1987;61:693–700. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.3.693-700.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liotta L A, Tryggvason K, Garbisa S, Hart I, Foltz C M, Shafie S. Metastatic potential correlates with enzymatic degradation of basement membrane collagen. Nature. 1980;284:67–68. doi: 10.1038/284067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lopata M A, Cleveland D W, Sollner-Webb B. High level transient expression of a chloramphenicol acetyl transferase gene by DEAE-dextran mediated DNA transfection coupled with a dimethyl sulfoxide or glycerol shock treatment. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5707–5717. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.14.5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumoto Y, Momoi Y, Watari T, Goitsuka R, Tsujimoto H, Hasegawa A. Detection of enhancer repeats in the long terminal repeats of feline leukemia viruses from cats with spontaneous neoplastic and nonneoplastic diseases. Virology. 1992;189:745–749. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90598-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morrison H L, Soni B, Lenz J. Long terminal repeat enhancer core sequences in proviruses adjacent to c-myc in T-cell lymphomas induced by a murine retrovirus. J Virol. 1995;69:446–455. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.446-455.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Negus R P, Stamp G W, Relf M G, Burke F, Malik S T, Bernasconi S, Allavena P, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Balkwill F R. The detection and localization of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in human ovarian cancer. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:2391–2396. doi: 10.1172/JCI117933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neil J C, Fulton R, Rigby M, Stewart M. Feline leukaemia virus: generation of pathogenic and oncogenic variants. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1991;171:67–93. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76524-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Donnell P V, Woller R, Chu A. Stages in development of mink cell focus-inducing (MCF) virus-accelerated leukemia in AKR mice. J Exp Med. 1984;160:914–934. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52a.Overbaugh, J. Personal communication.

- 53.Overbaugh J, Donahue P R, Quackenbush S L, Hoover E A, Mullins J I. Molecular cloning of a feline leukemia virus that induces fatal immunodeficiency disease in cats. Science. 1988;239:906–910. doi: 10.1126/science.2893454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Overbaugh J, Riedel N, Hoover E A, Mullins J I. Transduction of endogenous envelope genes by feline leukaemia virus in vitro. Nature. 1988;332:731–734. doi: 10.1038/332731a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pulverer B J, Kyriakis J M, Avruch J, Nikolakaki E, Woodgett J R. Phosphorylation of c-jun mediated by MAP kinases. Nature. 1991;353:670–674. doi: 10.1038/353670a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ray A, Tatter S B, May L T, Sehgal P B. Activation of the human “beta 2-interferon/hepatocyte-stimulating factor/interleukin 6” promoter by cytokines, viruses, and second messenger agonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6701–6705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riedel N, Hoover E A, Gasper P W, Nicolson M O, Mullins J I. Molecular analysis and pathogenesis of the feline aplastic anemia retrovirus, feline leukemia virus C-Sarma. J Virol. 1986;60:242–250. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.242-250.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohn J L, Overbaugh J. In vivo selection of long terminal repeat alterations in feline leukemia virus-induced thymic lymphomas. Virology. 1995;206:661–665. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roux P, Blanchard J M, Fernandez A, Lamb N, Jeanteur P, Piechaczyk M. Nuclear localization of c-Fos, but not v-Fos proteins, is controlled by extracellular signals. Cell. 1990;63:341–351. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90167-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy-Burman P. Endogenous env elements: partners in generation of pathogenic feline leukemia viruses. Virus Genes. 1995;11:147–161. doi: 10.1007/BF01728655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sarma P S, Log T. Subgroup classification of feline leukemia and sarcoma viruses by viral interference and neutralization tests. Virology. 1973;54:160–169. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Selten G, Cuypers H T, Berns A. Proviral activation of the putative oncogene pim-1 in MuLV-induced T cell lymphomas. EMBO J. 1985;4:1793–1798. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheets R L, Pandey R, Jen W C, Roy-Burman P. Recombinant feline leukemia virus genes detected in naturally occurring feline lymphosarcomas. J Virol. 1993;67:3118–3125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3118-3125.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sheets R L, Pandey R, Klement V, Grant C K, Roy-Burman P. Biologically selected recombinants between feline leukemia virus (FeLV) subgroup A and an endogenous FeLV element. Virology. 1992;190:849–855. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90924-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Short M K, Okenquist S A, Lenz J. Correlation of leukemogenic potential of murine retroviruses with transcriptional tissue preferences of the long terminal repeat. J Virol. 1987;61:1067–1072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.1067-1072.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soe L H, Shimizu R W, Landolph J R, Roy-Burman P. Molecular analysis of several classes of endogenous feline leukemia virus elements. J Virol. 1985;56:701–710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.3.701-710.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Speck N A, Renjifo B, Golemix E, Fredrickson T, Hartley J, Hopkins N. Mutation of the core or adjacent LVb elements of the Moloney murine leukemia virus enhancer alters disease specificity. Genes Dev. 1990;4:233–242. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Starkey C R, Lobelle-Rich P A, Granger S, Brightman B K, Fan H, Levy L S. Tumorigenic potential of a recombinant retrovirus containing sequences from Moloney murine leukemia virus and feline leukemia virus. J Virol. 1998;72:1078–1084. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1078-1084.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Timmers H T, Pronk G J, Bos J L, van der Eb A J. Analysis of the rat JE gene promoter identifies an AP-1 binding site essential for basal expression but not for TPA induction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:23–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tong L, Pav S, White D M, Rogers S, Crane K M, Cywin C L, Brown M L, Pargellis C A. A highly specific inhibitor of human p38 MAP kinase binds in the ATP pocket. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tsatsanis C, Fulton R, Nishigaki K, Tsujimoto H, Levy L, Terry A, Spandidos D, Onions D, Neil J C. Genetic determinants of feline leukemia virus-induced lymphoid tumors: patterns of proviral insertion and gene rearrangement. J Virol. 1994;68:8296–8303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8296-8303.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Watanabe H, Nakanishi I, Yamashita K, Hayakawa T, Okada Y. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (92 kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase) from U937 monoblastoid cells: correlation with cellular invasion. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:991–999. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.4.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]