Abstract

Background and aims:

Numerous prospective studies have examined sugar sweetened beverage (SSB) intake associated with weight gain or incident obesity. Because SSB accounts for only 33 % of added sugar (AS) intake, we investigated the associations of AS intake with change in weight and waist circumference and risk of developing obesity.

Methods and results:

At baseline (1985–86) Black and White women and men, aged 18–30 years, enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study and were followed for 30 years (2015–16). A diet history assessed dietary intake 3 times over 20 years. Multi-variable linear regression evaluated the associations of change in weight (n = 3306) and waist circumference (n = 3296) across quartiles of AS, adjusting for demographics, lifestyle factors, and anthropometrics. Proportional hazards regression analysis evaluated the associations of time-varying cumulative AS intake with risk of incident obesity (n = 4023) and abdominal obesity (n = 3449), adjusting for the same factors. Over 30 years of follow-up, greater AS intake was associated with gaining 2.3 kg more weight (ptrend = 0.01) and 2.2 cm greater change in waist circumference (ptrend = 0.005) as well as increased risk of incident obesity (HR 1.28; 95 % CI: 1.08–1.53) and incident abdominal obesity (HR 1.27; 95 % CI:1.02–1.60).

Conclusion:

Our findings are consistent with recommendations from the 2020e2025 U S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans to limit daily AS intake.

Keywords: Added sugar, Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, obesity, Cohort study, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

Obesity has been linked with a host of chronic conditions that are major sources of morbidity and mortality in the U.S.,including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and some cancers [1,2]. The cause of obesity is multifactorial [3]. In addition to genetic and environmental factors, modifiable behaviors such as excess screen time, limited physical activity, sleep, an unhealthy diet pattern, and excess energy intake are among the primary risk factors for obesity [4–6]. A Western diet pattern, commonly consumed in the U.S. and other countries, generally contains a significant number of extremely palatable foods and beverages high in added sugar (AS) that contribute few nutrients to the diet, potentially leading to excess energy intake [7]. Trends in added sugar intake declined between from 2003 to 04 to 2015–16 in the general U.S. adult population enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) [8]. Even though added sugar intake declined from 127 g of AS/day (~32 teaspoon (tsp); 508 kcal) in 2003–04 to 105 g of AS/day (~26 tsp; 406 kcal) in 2015–16, added sugar intake is still relatively high and contributing nutrient poor calories to the diet [8]. Furthermore, surveys in the U.S. and in Europe show lower AS intake with higher level of education [9,10]. A local surveillance study, the Minnesota Heart Survey conducted between 1980 and 2000, showed trends of increasing AS intake corresponded with increasing BMI during the same time period [11].

Because most prospective cohort studies have not assessed AS intake, sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) intake has been used as a proxy measure for AS intake [12]. Results from these studies have largely shown positive associations between SSB consumption and anthropometric measures of adiposity or weight gain [12-17]. However, since SSB consumption typically accounts for only 30%–40 % of total AS intake [18,19], it is important to capture the remaining AS in the diet, which will provide a more thorough depiction of AS and obesity. To date, we are not aware of any prospective cohort studies with long-term follow-up investigating the associations of AS intake with weight change, change in waist circumference, or risk of developing obesity in adults [20].

The objective of this study was to determine the associations of AS intake with change in weight and waist circumference in Black and White adults enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, and whether these associations differed by sex or education status as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Further, we aimed to determine the association of AS with the risk of developing obesity. We hypothesized that AS intake would be positively associated with weight gain, increased waist circumference, and risk of developing obesity among adults enrolled in the CARDIA study. We further hypothesized that women or those with less education would show greater weight gain and have greater risk of becoming obese with AS intake compared to men or those with higher education status.

2. Methods

The Institutional Review Boards at all four field centers approved the CARDIA study protocols. All CARDIA study participants gave written informed consent before participating in each CARDIA examination.

2.1. Study population

CARDIA is a longitudinal, population-based study conducted at four sites. CARDIA strives to evaluate the development of and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in 5115 Black and White male and female young adults aged 18–30 years at baseline (1985–1986). The four study sites are located in Birmingham, Alabama (n = 1178); Chicago, Illinois (n = 1109); Minneapolis, Minnesota (n = 1402); and Oakland, California (n = 1426). Study participants were examined at baseline (year 0 [Y0]) and re-examined during 8 follow-up exams at years 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30. At Y30, 71 % of surviving participants attended the follow-up exam (n = 3358). Details of the study have been previously reported [21,22]. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the time of exposure and outcome assessments across exam years in the study.

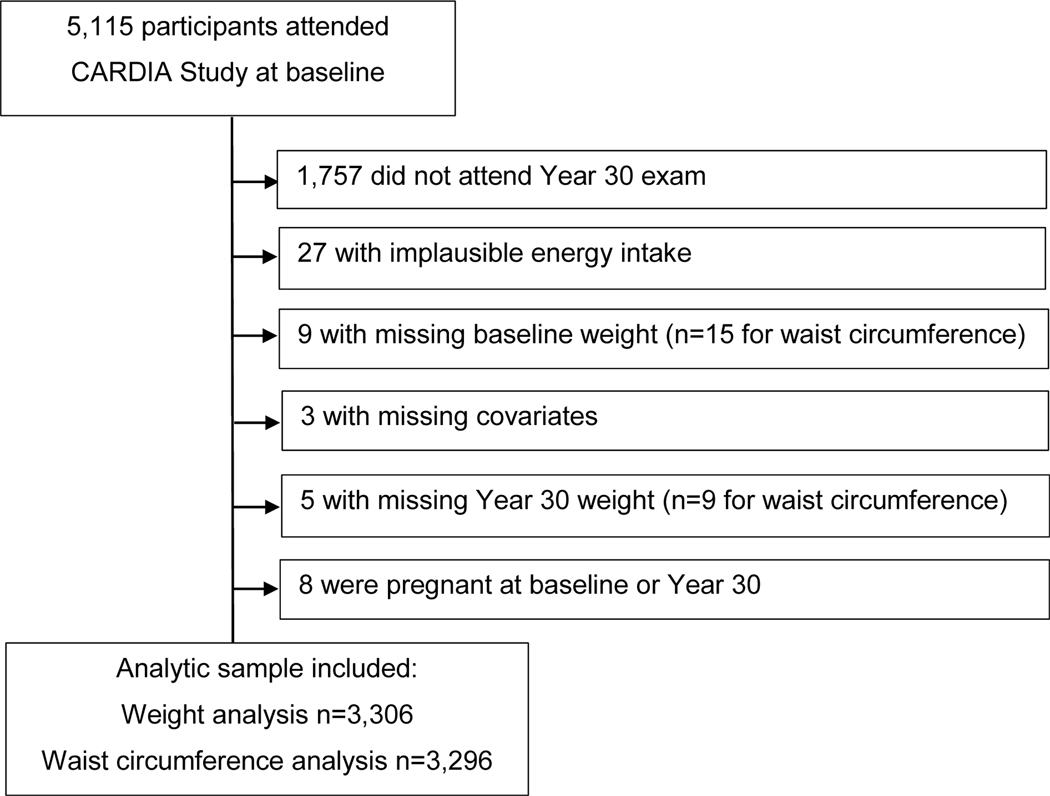

A flowchart of exclusion criteria and sample sizes for the weight and weight change analyses is shown in Fig. 1. Observations were excluded from the analyses for missing or implausible energy intake (<600 kcal/day or >6000 kcal/day for women and <800 kcal/day or >8000 kcal/day for men); missing Y0 weight or Y0 waist circumference, as appropriate; missing Y0 covariates physical activity, drinking, or smoking status; missing Y30 wt or Y30 waist circumference, as appropriate; and those who were pregnant at Y0 or Y30. Participants who were obese at Y0 (n = 598) or participants who were abdominally obese at Y0 (n = 1287) were excluded to determine incident obesity or abdominal obesity by Y30, respectively, for the proportional hazards regression analyses. The resulting sample sizes for change in weight, change in waist circumference, incident obesity, and incident abdominal obesity analyses were n = 3,306, n = 3,296, n = 4,023, and n = 3,449, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Diet assessment

Dietary intake was assessed by trained and certified interviewers who administered the CARDIA diet history during in-person interviews at Y0, Y7, and Y20 [23]. The diet history’s validity was previously determined [24]. During the interview, participants provided information about consumed foods and beverages including the brand name, portion size, and frequency (per day, week, or month). Participants were asked if they consumed SSBs, candy, sugar/honey/jams/syrup, refined grain desserts, refined grain and whole grain products, fruit and fruit juice, vegetables, legumes, nuts, red and processed meat, eggs, poultry, fish and seafood, dairy, diet beverages, and alcohol. Nutrients, ingredients (including AS), and food groupings were determined by the Nutrition Data System for Research (NDSR) computer program developed by the University of Minnesota Nutrition Coordinating Center. AS, our exposure of interest and ingredient in the NDSR database, was defined as a caloric sweetener added to foods or drinks that is not considered naturally occurring in the food or beverage. One tsp of AS is about 4 g (16 kcal). Using principal components analysis, the Western diet pattern was derived including all of the above food and beverages groups, except for SSB.

2.3. Anthropometric assessment

Weight and height were measured, without shoes, during each CARDIA exam by trained and certified technicians. Weight was measured on a calibrated balance beam scale and recorded to the nearest 0.2 kg. Height was measured using a vertical ruler and recorded to the nearest 0.5 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kg divided by height in m2. Obesity was defined as BMI≥30 kg/m2 or not obese BMI<30 kg/m2 [25].

During each CARDIA exam, waist circumference, measured to the nearest 0.5 cm using a cloth tape, was used to determine abdominal obesity. As defined by the American Heart Association, abdominal obesity is waist circumference ≥102 cm for males and ≥80 cm for females [26].

2.4. Other covariates

Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race, field center, and years of education were collected using standardized questionnaires. Lifestyle factors, including physical activity, smoking status, and drinking status, were assessed by other questionnaires. Education was dichotomized as greater than high school graduate vs high school or fewer years of education. Status of current smoking and current alcohol intake were dichotomized as yes or no. Physical activity level was determined according to responses on the CARDIA Physical Activity Questionnaire [27]. Additionally, history of pregnancy was recorded. Diabetes was defined as use of diabetes medication, a fasting blood glucose concentration of ≥126 mg/dL, 2-h post-challenge glucose >200 mg/dL from an oral glucose tolerance test, an HbA1c ≥48 mmol/mol (6.5 %), and/or physician diagnosis.

2.5. Statistical methods

SAS version 9.4 was used for all data analysis (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Quartiles of average AS intake were created using the average of AS intake at Y0, Y7, and Y20. The same was done for creating quartiles of average SSB intake. The correlations for AS and SSB between Y0 and Y20 were 0.35 and 0.31 (both p < 0.001), respectively. Weight change was calculated as weight at Y30 minus weight at Y0. Similarly, change in waist circumference was calculated as waist circumference at Y30 minus waist circumference at Y0. Baseline characteristics and dietary intake were reported as mean standard error (SE) or frequency (%) across quartiles of baseline AS intake and adjusted for age, sex, race, education, field center, and energy intake, as appropriate in Table 1. The unadjusted means and standard deviations (SD) for baseline characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean (SE) and frequency of baseline characteristics stratified across quartiles of added sugar intake among 3306 CARDIA study participants.

| Characteristics | Quartiles of Baseline Added Sugar Intake (g/d) |

ptrend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 826) | 2 (n = 827) | 3 (n = 827) | 4 (n = 826) | ||

| Added sugar, mean g/d (range) | 23.5 (<36.2) | 47.8 (36.2–61.0) | 78.6 (61.1–101.6) | 163.5 (≥101.7) | |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||||

| Age, yr | 25.0 (0.17) | 24.5 (0.16) | 24.4 (0.16) | 23.8 (0.17) | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 29.1 | 39.2 | 48.9 | 56.7 | <0.001 |

| White, % | 72.9 | 55.5 | 44.7 | 37.7 | <0.001 |

| Education, % | 96.9 | 93.3 | 93.3 | 86.7 | 0.05 |

| >High school | |||||

| Lifestyle Characteristics | |||||

| Physical activity score | 447 (13.5) | 417 (12.6) | 389 (12.7) | 357 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Current smoking, % | 20.7 | 21.2 | 24.5 | 36.0 | 0.001 |

| Current drinking, % | 88.8 | 88.3 | 86.9 | 84.8 | 0.02 |

| Physical Characteristics | |||||

| Weight, kg | 71.3 (0.71) | 71.3 (0.66) | 71.3 (0.67) | 71.4 (0.72) | 0.97 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 78.1 (0.50) | 78.3 (0.47) | 78.4 (0.47) | 78.7 (0.51) | 0.36 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, field center, and energy intake.

General linear regression analysis evaluated the associations of AS intake with weight, weight change, waist circumference, and change in waist circumference by Y30. Models were adjusted for baseline age, sex, race, education, field center, energy intake, physical activity, status of current smoking and alcohol, height, baseline weight (or waist circumference, as appropriate), and nutrient intake (saturated fat, protein, fiber, folic acid, potassium, vitamin C, calcium, vitamin D, iron, and magnesium). Models were further adjusted for mediators of obesity, including history of pregnancy [28] and diabetes status [29,30]. A similar model was developed for SSB, except that the model was adjusted for the Western diet pattern instead of nutrient intake. Interactions by each of sex and education status were tested on the associations of AS with outcomes, but were not significant (pinteraction>0.10). To determine whether linearity was a good dose-response fit to the associations between AS and weight gain and change in waist, restricted cubic spline regression analyses were conducted. The cubic spline models suggested a linear fit to the data (p < 0.003), while the p for nonlinearity was high (p > 0.90).

Proportional hazards regression analysis evaluated the time-dependent associations of AS intake with risk of becoming obese and abdominally obese. Follow-up time was calculated as time to outcome occurrence, death, or last follow-up. A cumulative average AS intake was calculated based on the follow-up time: 1) for follow-up time >0 and ≤ 7 years, AS intake from Y0 was used; 2) for follow-up time >7 and ≤ 20 years, the average AS intake of Y0 and Y7 was used; and 3) for follow-up time >20 years, the average of AS intake at Y0, Y7, and Y20 was used. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were estimated across quartiles of AS intake. Models were adjusted for the same covariates as in the general linear regression analysis. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by the log of time interaction method and was not violated.

3. Results

In this study, about 31 % participants consumed less than 10 % of energy from AS, which aligns with the 2020e2025 U S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) recommendation [19]. Table 1 shows mean (SE) for baseline characteristics across the quartiles of mean AS intake. Study participants with greater AS intake were more likely to be younger, female, Black, less educated, less physically active, and a current smoker, and were less likely to be a current drinker (ptrend≤0.05). There were no significant trends across quartiles of AS intake for either weight or waist circumference at baseline (both ptrend >0.05). Unadjusted mean (SD) for baseline characteristics stratified across quartiles of AS intake are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Greater AS intake was associated with lower nutrient intake, including protein, fiber, potassium, vitamin C, calcium, vitamin D, iron, and magnesium (all ptrend<0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, greater intake of AS was associated with lower intakes of many foods and beverages, including whole grains, fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts, poultry, eggs, fish/seafood, alcohol, diet beverages, and fruit juice (all ptrend<0.001). Conversely, with more AS consumption, participants were more likely to have greater energy intakes and consume more SSBs, candy, and refined grains (ptrend<0.001). There was no significant difference in the consumption of saturated fat, folic acid, red and processed meat, eggs, and dairy products across the quartiles of AS (ptrend>0.05).

Table 2.

Mean (SE) baseline daily nutrient and food intake stratified across quartiles of added sugar intake among 3306 CARDIA study participants.

| Dietary Intake | Quartiles of baseline Added Sugar Intake (g/d) |

ptrend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 826) | 2 (n = 827) | 3 (n = 827) | 4 (n = 826) | ||

| Added sugar, g/d (range) | 23.5 (<36.2) | 47.8 (36.2–61.0) | 78.6 (61.1–101.6) | 163.5 (≥101.7) | |

| Nutrient intake | |||||

| Energy, kcal | 1719 (37.0) | 2009 (35.1) | 2372 (35.3) | 3172 (34.0) | <0.001 |

| SFA, g | 44.9 (0.6) | 44.9 (0.5) | 45.3 (0.30) | 45.0 (0.6) | 0.71 |

| Protein, g | 109.2 (1.1) | 106.6 (1.1) | 103.3 (1.1) | 94.2 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Crude fiber, g | 6.1 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.1) | 5.3 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Folic acid, μg | 448.7 (46.2) | 405.9 (42.9) | 382.6 (43.2) | 380.2 (46.6) | 0.23 |

| Potassium, mg | 3891 (40.9) | 3770 (38.0) | 3610 (38.2) | 3072 (41.2) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin C, mg | 187.6 (5.2) | 176.1 (4.8) | 164.8 (4.9) | 138.6 (5.3) | <0.001 |

| Calcium, mg | 1245 (23.0) | 1269 (21.4) | 1245 (16.7) | 1090 (23.2) | <0.001 |

| Vitamin D, μg | 7.0 (0.2) | 7.1 (0.2) | 7.1 (0.2) | 5.8 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Iron, mg | 18.5 (0.3) | 18.3 (0.2) | 18.2 (0.2) | 17.2 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Magnesium, mg | 391.5 (4.6) | 386.6 (4.3) | 369.7 (4.3) | 319.9 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Food group intake, (servings/d) | |||||

| SSB | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.1) | 5.2 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Diet beverages | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Candy | 0.1 (0.02) | 0.2 (0.02) | 0.3 (0.02) | 0.5 (0.02) | <0.001 |

| Refined grains | 4.6 (0.1) | 4.5 (0.1) | 4.8 (0.1) | 5.3 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Whole grains | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Fruit, fruit juice | 2.4 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.1) | 1.9 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Vegetables | 4.4 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Legumes | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.02) | 0.21 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.02) | <0.001 |

| Nuts | 0.8 (0.07) | 0.7 (0.06) | 0.6 (0.06) | 0.4 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| Meat | 4.3 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.1) | 4.2 (0.1) | 0.99 |

| Poultry | 1.5 (0.08) | 1.3 (0.07) | 1.1 (0.07) | 0.9 (0.08) | <0.001 |

| Eggs | 0.74 (0.03) | 0.69 (0.03) | 0.69 (0.03) | 0.68 (0.02) | 0.15 |

| Fish/seafood | 1.3 (0.07) | 1.2 (0.07) | 1.0 (0.07) | 0.8 (0.08) | <0.001 |

| Dairy products | 2.9 (0.1) | 3.1 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.1) | 2.72 (0.1) | 0.54 |

| Alcohol | 1.3 (0.06) | 1.2 (0.06) | 1.0 (0.06) | 0.7 (0.06) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, field center, and energy intake.

SFA = saturated fatty acids; SSB = sugar sweetened beverages.

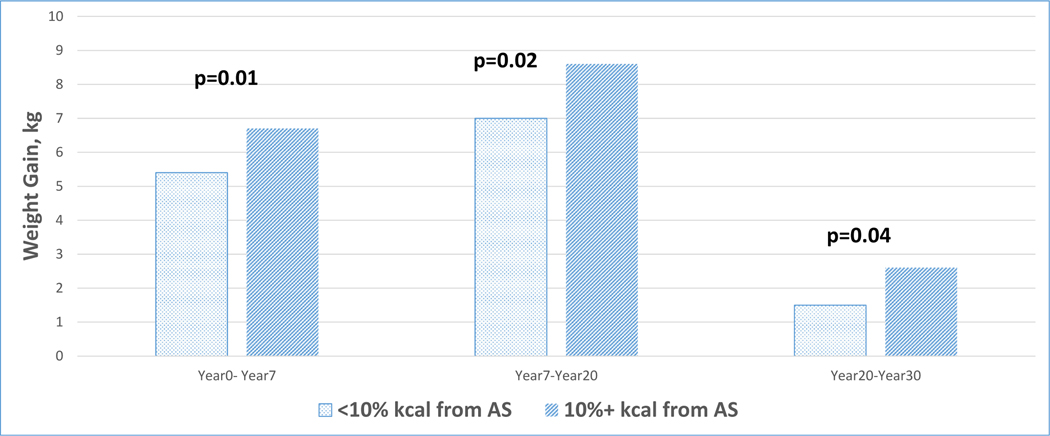

As shown in Table 3, mean average AS intake was associated with weight, weight gain, waist circumference, and change in waist circumference at Y30 (all ptrend≤0.02). Participants in quartile 4 weighed on average 2.3 kg more than those in quartile 1 (89.1 kg vs. 86.8 kg, respectively). On average, participants in quartile 4 gained 18.4 kg, while those in quartile 1 gained 16.1 kg. Participants in quartile 4 had on average about 2.5 cm larger waist circumference than those in quartile 1 (98.1 cm vs. 95.6 cm, respectively). Further, on average, participants in quartile 4 increased their waist circumference by 20.1 cm, while those in quartile 1 increased their waist circumference by 17.9 cm. All associations remained significant after further adjustment for history of pregnancy and diabetes status (all ptrend<0.05, data not shown). Furthermore, for each 1 teaspoon increase of added sugar intake, weight increased by 0.11 kg (p < 0.001) and waist circumference increased by 0.08 cm (p = 0.003). As shown in Fig. 2, weight gain was significantly less among participants who consumed <10 % of energy from AS compared to those who consumed ≥10 % energy from AS during follow-up.

Table 3.

Change in weight and waist circumference at Year30 (Y30) stratified across quartiles of added sugar intake among CARDIA study participants.

| Y30 Outcome | Quartiles of Average (Y0, 7, 20) Added Sugar (AS) Intake (g/d) |

ptrend | Per 1 tsp (4 g) increase in AS | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Added sugar (g/d), mean (range) | 33.4 (<45.5) | 56.6 (45.5–67.7) | 83.4 (67.7–103.3) | 151.7 (>103.4) | β (SE) | ||

| Weight | (n = 826) | (n = 827) | (n = 827) | (n = 826) | (n = 3306) | ||

| Weight, kg | 86.8 (0.83) | 88.0 (0.80) | 88.8 (0.80) | 89.1 (0.81) | 0.01 | 0.11 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| Weight gain, kg | 16.1 (0.83) | 17.3 (0.80) | 18.1 (0.80) | 18.4 (0.81) | 0.01 | 0.11 (0.03) | <0.001 |

| Waist | (n = 824) | (n = 824) | (n = 824) | (n = 824) | (n = 3296) | ||

| Waist circumference, cm | 95.6 (0.68) | 96.7 (0.66) | 97.3 (0.65) | 98.1 (0.67) | 0.005 | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.002 |

| Change in waist, cm | 17.9 (0.67) | 18.7 (0.65) | 19.3 (0.64) | 20.1 (0.66) | 0.005 | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.002 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, education, field center, energy intake, physical activity, smoking status, drinking status, baseline weight (or waist circumference as appropriate), height, and nutrient intake (saturated fat, protein, fiber, folic acid, potassium, vitamin C, calcium, vitamin D, iron, magnesium).

Fig. 2.

30-year weight gain among women and men consuming less than 10% of calories from added sugar compared to those consuming 10% or more calories from added sugar.

Over 30 years of follow-up, greater AS intake was associated with about 28 % increased risk of developing obesity (HR 1.28; 95 % CI: 1.08–1.53) and 27 % higher risk of developing abdominal obesity (HR 1.27; 95 % CI:1.02–1.60) (Table 4). These associations remained significant after further adjustment for history of pregnancy and diabetes status (data not shown).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios (HR) of incident obesity stratified across quartiles of cumulative added sugar intake among CARDIA study participants over 30 years of follow-up.

| Y30 Outcome | Quartiles of Cumulative Added Sugar Intake (g/d) |

ptrend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Added sugar, g/d (range) | 32.4 (<45.4) | 57.4 (45.5–70.4) | 86.9 (70.5–107.8) | 161.2 (>108.0) | |

| Incident Obesity (n = 4023) | (n = 1005) | (n = 1006) | (n = 1006) | (n = 1006) | |

| No. of cases | 430 | 413 | 443 | 470 | |

| Unadjusted model | 1 | 0.96 (0.84–1.11) | 1.09 (0.96–1.25) | 1.22 (1.07–1.40) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 HR (95 % CI) | 1 | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 1.07 (0.91–1.27) | 0.23 |

| Model 2 HR (95 % CI) | 1 | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 1.18 (1.01–1.37) | 1.28 (1.08–1.53) | 0.001 |

| Incident Abdominal obesity (n = 3449) | (n = 862) | (n = 862) | (n = 863) | (n = 862) | |

| No. of cases | 289 | 236 | 461 | 526 | |

| Unadjusted model | 1 | 1.42 (1.18–1.70) | 2.09 (1.75–2.50) | 2.42 (2.03–2.89) | <0.001 |

| Model 1 HR (95 % CI) | 1 | 1.07 (0.89–1.30) | 1.23 (1.02–1.49) | 1.36 (1.10–1.68) | 0.002 |

| Model 2 HR (95 % CI) | 1 | 1.03 (0.86–1.26) | 1.10 (0.91–1.34) | 1.27 (1.02–1.60) | 0.03 |

Model 1 is adjusted for age, sex, race, education, field center, energy intake.

Model 2 is adjusted for age, sex, race, education, field center, energy intake, physical activity, smoking, alcohol intake, baseline weight (or waist circumference as appropriate), height, and nutrient intake (saturated fat, protein, fiber, folic acid, potassium, vitamin C, calcium, vitamin D, iron, magnesium).

Consumption of SSBs was also associated with increased weight, weight change, waist circumference, and change in waist circumference at Y30 (all ptrend≤0.003) (Supplementary Table 2). At Y30, those in quartile 4 of SSB consumption weighed more and had a larger waist circumference than those in quartile 1. All associations remained significant after further adjustment for history of pregnancy and diabetes status (all ptrend<0.05, data not shown). Over 30 years of follow-up, greater SSB intake was associated with an approximate 23 % increased risk of developing obesity (HR 1.23; 95 % CI:1.05–1.45) and about 25 % increased risk of developing abdominal obesity (HR: 1.25; 95 % CI: 1.02–1.54) (Supplementary Table 3).

4. Discussion

Among a large community-based cohort of Black and White individuals, AS and SSB intakes were positively associated with weight gain and change in waist circumference over a 30 year follow-up period. Additionally, greater AS and SSB intake were associated with increased risks of incident obesity and abdominal obesity. Characteristics of individuals who consumed more AS were younger, female, Black, less educated, less physically active, current smokers, and fewer were current drinkers.

To our knowledge, there are no published prospective studies AS intake and weight gain or risk of obesity in young adults, but there are numerous studies about SSB intake relative to these outcomes [5,12,17]. Many prospective studies among adult populations of varying nationalities have reported positive associations between SSB consumption and waist circumference, weight gain, and development of obesity [13–17]. Results from cross-sectional studies have likewise shown greater SSB intake associated with higher prevalence of obesity [12]. However as previously stated, SSB consumption accounts for only 30–40 % of total AS intake [18,19].

Experimental studies have identified numerous mechanisms linking AS consumption with weight gain. Among these, and consistent with the traditional model of adiposity, AS is a source of nutrient-poor calories that contribute to a positive energy balance [5,8–10], which promotes adipose tissue accumulation [31]. Second, diets high in AS have been shown to shift the microbiota composition towards one that favors an obese phenotype that is more efficient at extracting energy from food and beverages consumed [32]. Finally, sugar intakes have been shown to differentially disrupt hypothalamic satiety signals [33,34], induce leptin resistance [35], and promote release of the neurotransmitter, dopamine [36,37]; if the case in humans, then excessive or compulsive eating behavior resulting in a positive energy balance and obesity may follow. Critically, the adjustment for energy intake in this analysis represents a potential over-adjustment, since intake may be partially mediated by AS intake if it is indeed affecting satiety signals and or inducing an addictive, dopamine reward-based eating behavior.

Our findings have important implications given the ongoing obesity epidemic in the U.S. and continued, unhealthy trend in AS intake among adults [8,10]. Critically, obesity increases the risks of developing chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, cancers, and Alzheimer’s and dementia related disease (1, 38–41). Similarly, abdominal obesity has also been shown to increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and myocardial infarction [42]. Limiting AS intake, by decreasing consumption of SSBs and foods high in AS, may reduce the risk of developing obesity and abdominal obesity, therefore reducing the prevalence of these adverse health outcomes. Over 30 years of follow-up, we found 4.5 kg less weight gain among those who consumed less than 10 % of energy from AS compared with greater AS consumption (Fig. 2).

This study has some limitations including participant’s self-reported dietary intake. It is likely that some foods and beverages were under- or over-reported potentially resulting in misclassification. However, clinical studies have demonstrated under-reporting of AS-rich foods by adults [43]; thus, the association would be underestimated toward the null. The study also had many strengths. With a prospective study design, data were collected over 30 years and followed a large study population of both Black and White females and males aged 18–30 at baseline living in the Midwest, Alabama, and California. Weight and waist circumference were measured at all exams using standardized protocols by trained and certified data observers. Additionally, dietary intake was administered by trained and certified diet data collectors on three different occasions over twenty years. Repeated administration of the diet history would account for change in dietary intake, including total AS and SSBs. In contrast to other prospective studies, we reported the association of both AS and SSBs associated with body composition measures.

5. Conclusion

We observed positive associations of AS with weight gain and risk of incident obesity in a population of Black and White healthy young adults at baseline up to 30 years of follow-up.

Our findings are consistent with recommendations from the American Heart Association and the 2020e2025 DGA that promote limiting AS intake [19]. Consuming less AS may be one strategy for maintaining weight or gaining less weight over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Author contributions: EJE, SYY, LMS, and DRJ designed and conducted the research; XZ and SYY analyzed the data; EJE, SYY, BTS, and LMS wrote the paper; SYY, BTS, JMS, and DRJ critically reviewed and revised the paper for important content; all authors read and approved the final manuscript; and LMS had primary responsibility for final content.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) grants [R21 HL135300-01 (LM Steffen) and R01 HL150053 (LM Steffen)] and the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is supported by contracts HHSN268201800003I, HSN268201800004I, HHSN268201800005I, HHSN268201800006I, and HHSN268201800007I from the NIH/NHLBI.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2023.10.022.

Availability of data

All CARDIA Exam materials, including protocols, manual of operations, data collection forms, and consent forms, are available on the CARDIA website (www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu). Please contact the CARDIA Coordinating Center to obtain study data (coc@uab.edu).

References

- [1].Health risks of overweight and obesity. Version current February. In: National Institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases; 2018. Internet, https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/health-risks. [Accessed 23 January 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2019. NCHS data brief, No, 2020 No. 395. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Toward precision approaches for the prevention and treatment of obesity. JAMA 2018;319(3):223–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Siddarth D. Risk factors for obesity in children and adults. J Invest Med 2013;61(6):1039–42. 10.2310/JIM.0b013e31829c39d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Malik VS, Hu FB. Sweeteners and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: the role of sugar-sweetened beverages. Curr Diabetes Rep 2012;12:195–203. 10.1007/s11892-012-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Omer T. The causes of obesity: an in-depth review. Adv Obes Weight Manag Control 2020;10(3):90–4. 10.15406/aowmc.2020.10.00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Azzam A. Is the world converging to a ‘Western diet’? Publ Health Nutr 2021;24(2):309–17. 10.1017/S136898002000350X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Marriott BP, Hunt KJ, Malek AM, Newman JC. Trends in intake of energyand total sugar from sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States among children and adults. NHANES 2019. Aug 25;11(9):2004. 10.3390/nu11092004. 2003–2016. Nutrients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Azais-Braeson V, Sluik D, Maillot M, Kok F, Moreno LA. A review of total & added sugar intakes and dietary sources in Europe. Nutr J 2017;16:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ricciuto L, Fulgoni VL, Gaine PC, Scott MO, DiFrancesco L. Sources of added sugars intake among the U.S. population: analysis by selected sociodemographic factors using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–18. Front Nutr 2021;8:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang H, Steffen LM, Zhou X, Harnack L, Luepker RV. Consistency between increasing trends in added-sugar intake and body mass index among adults: the Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–1982 to 2007–2009. Am J Publ Health 2013;103:501–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 2006. Aug; 84(2):274–88. 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Funtikova AN, Subirana I, Gomez SF, Fito M, Elosua R, Benitez-Arciniega AA, Schroder H. Soft drink consumption is positively associateold with increased waist circumference and 10-year incidence of abdominal obesity in Spanish adults. J Nutr 2015; 145:328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA 2004;292(8):927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Boggs DA, Rosenberg L, Coogan PF, Makambi KH, Adams-Campbell LL, Palmer JR. Restaurant foods, sugar-sweetened soft drinks, and obesity risk among young African American women. Ethn Dis 2013;23:445–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lim L, Banwell C, Bain C, Banks E, Seubsman S, Kelly M, Sleigh A. Sugar sweetened beverages and weight gain over 4 years in a Thai national cohort – a prospective analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e95309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Qin P, Li Q, Zhao Y, Chen Q, Sun X, Liu Y, Li H, Wang T, Chen X, Zhou Q, Guo C, Zhang D, Tian G, Liu D, Qie R, Han M, Huang S, Wu X, Li Y, Feng Y, Yang X, Hu F, Hu D, Zhang M. Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and all-cause mortality: a dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2020;35:655–71. 10.1007/s10654-020-00655-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yuhas M, Hendrick V, Zoellner J. Consumption of added sugars by rural residents of Southwest Virginia. J Appalach Health 2020;2:53–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Available at:. ninth ed. December 2020. DietaryGuidelines.gov. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Faruque S, Tong J, Lacmanovic V, Agbonghae C, Minaya DM, Czaja K . The dose makes the poison: sugar and obesity in the United States - a review. Pol J Food Nutr Sci 2019;69:219–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Liu K, Savage PJ. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41:1105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hughes GH, Cutter G, Donahue R, Friedman GD, Hulley S, Hunkeler E, Jacobs DR, Liu K, Orden S, Pirie P, et al. Recruitment in the coronary Artery disease risk development in young adults (cardia) study. Contr Clin Trials 1987;8:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].McDonald A, Van Horn L, Slattery M, Hilner J, Bragg C, Caan B, Jacobs D Jr, Liu K, Hubert H, Gernhofer N, et al. The CARDIA dietary history: development, implementation, and evaluation. J Am Diet Assoc 1991;91:1104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Liu K, Slattery M, Jacobs DR, Cutter G, McDonald A, Van Horn L, Hilner JE, Caan B, Bragg C, Dyer A, et al. A study of the reliability and comparative validity of the CARDIA dietary history. Ethn Dis 1994;4:15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Clinical Guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults-the evidence report. National Institutes of health. Obes Res 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. ECrratum in: Obes Res 1998;6(6):464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. American heart association; national heart, Lung, and blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart association/national heart, Lung, and blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 2005; 112(17):2735–52. Erratum in: Circulation. 2005;112(17):e297, e298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jacobs DR, Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and reliability of short physical activity history. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 1989;9:448–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Melzer K, Schutz Y. Pre-pregnancy and pregnancy predictors of obesity. Int J Obes 2010;34(Suppl 2):S44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kahn BB, Flier JS. Obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2000; 106(4):473–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Russell-Jones D, Khan R. Insulin-associated weight gain in diabetes – causes, effects and coping strategies. Diabetes Obes Metabol 2007;9(6):799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Romieu Romieu I, Dossus L, Barquera S, Blottière HM, Franks PW, Gunter M, Hwalla N, Hursting SD, Leitzmann M, Margetts B, Nishida C, Potischman N, Seidell J, Stepien M, Wang Y, Westerterp K, Winichagoon P, Wiseman M, Willett WC. IARC working group on Energy Balance and Obesity. Energy balance and obesity: what are the main drivers? Cancer Causes Control 2017. Mar;28(3):247–58. 10.1007/s10552-017-0869-z. Epub 2017 Feb 17. PMID: 28210884; PMCID: PMC5325830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Garcia K, Ferreira G, Reis F, Viana S. Impact of dietary sugars on gut microbiota and metabolic health. Diabetology 2022;3:549–60. 10.3390/diabetology3040042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cha SH, Wolfgang M, Tokutake Y, Chohnan S, Lane MD. Differential effects of central fructose and glucose on hypothalamic malonyl-CoA and food intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008. Nov 4; 105(44):16871–5. 10.1073/pnas.0809255105. Epub 2008 Oct 29. PMID: 18971329; PMCID: PMC2579345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Colley DL, Castonguay TW. Effects of sugar solutions on hypothalamic appetite regulation. Physiol Behav 2015 Feb;139:202–9. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.025. Epub 2014 Nov 14. PMID: 25449399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vasselli JR. The role of dietary components in leptin resistance. Adv Nutr 2012. Sep 1;3(5):736–8. 10.3945/an.112.002659. PMID: 22983859; PMCID: PMC3648762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Rada P, Avena NM, Hoebel BG. Daily bingeing on sugar repeatedly releases dopamine in the accumbens shell. Neuroscience 2005; 134(3):737–44. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.043. PMID: 15987666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fernandes AB, Alves da Silva J, Almeida J, Cui G, Gerfen CR, Costa RM, Oliveira-Maia AJ. Postingestive modulation of food seeking depends on vagus-mediated dopamine neuron activity. Neuron 2023. Feb 15;111(4):595. 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.01.025. Erratum for: Neuron. 2020 Jun 3;106(5):778–788.e6. PMID: 36796329; PMCID: PMC9943146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity causes & consequences. Version current 22 March. 2021. Internet: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html. [Accessed 10 April 2021].

- [39].Must A, Spandano J, Coakley E. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 1999;282:1523–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nianogo RA, Rosenwohl-Mack A, Yaffe K, Carrasco A, Hoffmann CM, Barnes DE. Risk factors associated with alzheimer disease and related dementias by sex and race and ethnicity in the US. JAMA Neurol 2022. Jun 1;79(6):584–91. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.0976. PMID: 35532912; PMCID: PMC9086930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Publ Health 2009. Mar 25;9:88. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. PMID: 19320986; PMCID: PMC2667420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cameron AJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N, Zimmet PZ, Barr ELM, Tonkin AM, Magliano DJ, Murray SG, Shaw JE, Welborn T. Health and mortality consequences of abdominal obesity: evidence from the AusDiab study. Med J Aust 2009;191:202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Poppitt SD, Swann D, Black AE, Prentice AM. Assessment of selective under-reporting of food intake by both obese and non-obese women in a metabolic facility. Int J Obes 1998;22:303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All CARDIA Exam materials, including protocols, manual of operations, data collection forms, and consent forms, are available on the CARDIA website (www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu). Please contact the CARDIA Coordinating Center to obtain study data (coc@uab.edu).