Abstract

There has been an increased understanding of the protective effect of two or more hours in high lux light on the development and progression of myopia. The aim of myopia management is to reduce the incidence of high myopia and sight-threatening myopic complications. Equally important are the sight-threatening complications of ultraviolet radiation (UVR) on the eye and adnexal structures. This review will analyze the literature for both these epidemics to help guide public health policy. Whilst increasing childhood high lux light exposure is important, consideration of a holistic eye health policy should ensure that UV eye diseases are also prevented. The advent of ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence photography has increased our understanding that significant UV eye damage occurs in childhood, with 81% of children aged 12–15 years having signs of UV eye damage. Hence, the need to reduce myopia and protect from UV-related eye diseases needs simultaneous consideration. Advocating for eye protection is important, particularly as the natural squint reflex is disabled with dark sunglasses lenses. The pathways UV reaches the eye need to be considered and addressed to ensure that sunglasses offer optimum UV eye protection. The design of protective sunglasses that simultaneously allow high lux light exposure and protect from UVR is critical in combating both these epidemics.

Keywords: Age-related macular degeneration, myopia, pterygium, sunglasses, ultraviolet-related eye diseases

Introduction

Myopia is an increasingly common eye disorder, with its prevalence expected to reach 52% by 2050.[1,2] It is predicted that 1 billion people worldwide will have high myopia with refractive errors >–6D or axial lengths > 26 mm.[1] High myopia is expected to become leading cause of permanent blindness worldwide in the adulthood. The sight-threatening complications of myopia include retinal detachment, neovascular membrane secondary to myopic macular degeneration, glaucoma, and presenile cataracts.[3,4]

Genetics and environmental factors contribute to myopia development. A meta-analysis and systemic review established that the incidence of myopia decreases with increased time spent outdoors due to exposure to high lux light.[5] A key measure to limit the development and progression of myopia is spending at least 2.5 hours outdoors daily to expose the child’s eye to high-lux light.[5]

Ultraviolet (UV) skin and eye damage occur primarily in childhood and the diseases typically manifest in later adulthood. UV-related eye diseases include a range of ocular and eyelid diseases, ranging from periocular skin cancers,[6] ocular surface tumors,[7] pterygium[8] and pinguecula, cataracts,[9,10,11] and age-related macular degeneration (AMD).[12]

This review will present a brief overview of the evidence for increased outdoor light exposure with high lux light to reduce myopia progression and assess the evidence regarding UV eye protection for children to simultaneously reduce UV damage to the child’s eye, thereby reducing UV-related eye disease later in life. The evidence for combining frame and lens design in sunglasses to maximize eye protection in children will be considered. Thus, increasing outdoor light exposure with high-grade UV eye protection should be linked together in public health policy.

Methodology

The PubMed database was searched, with no date restrictions, using the search terms “UV-related diseases,” “pterygium,” “pinguecula,” and “skin cancer” as signs of significant childhood UV exposure to correlate against “axial length,” “myopia,” and “refractive error”. The term “macular degeneration” was also cross referenced against “Ultraviolet light” and “refractive error”. The analyzed studies compared the prevalence of the disease worldwide, with UV exposure varying from outdoor activity (working or leisure), latitude, and altitude. The literature was also reviewed using the search terms “UV radiation and eye,” “UV eye protection,” and “sunglasses” to analyze the key components of eye protection.

Evidence for Myopia Intervention with Increased Outdoor Exposure

Various animal studies have investigated the effect of intensity of light and its effects on myopia progression. Seminal chicken experiments exposed deprivation-induced myopic chicks to different light intensities, measured as lux, demonstrating the effect of high lux light in retarding myopia progression.[13] Other animal studies, including on chicks,[14] rhesus monkeys,[15] and tree shrews,[16] used UV-free lighting systems to inhibit scleral growth rates experimentally. Myopia was induced in these animals with either form deprivation or defocus, and this was modified by UV-free lighting systems that were shown to modify the normal emmetropization process.

Epidemiological studies show a similar association with both an increase in myopia progression in low light levels and reduced progression in high light levels. Rose et al. compared Chinese children living in Sydney to those in Singapore. In Sydney, the kids had an average of 13.5 outdoor hours per week with a prevalence of 3.3% myopia compared to the 3.05 outdoor hours per week for the Chinese children in Singapore and a myopia prevalence of 29.1%.[17] Seasonal differences in myopia progression have also been seen in Chinese, Norwegian, and Czech children, with greater progression in myopia during the winter months.[18,19,20]

Intervention has also been shown to reduce the incidence of myopia by increasing the time 6-year-old Chinese children spend outdoors by 40 min a day.[21] Rose et al.[22] analyzed the outdoor activity compared with near work and concluded that light intensity rather than the absence of near work was the critical factor. Ho et al.,[23] in their meta-analysis of the dose-response relationship between outdoor light exposure and myopia indicators, found that more than 120 min of daily outdoor light exposure decreased myopia incidence by 50%, spherical equivalent refraction by 32.9%, and axial elongation by 24.9% for Asian children aged 4–14 years. Furthermore, <40 min outdoors daily is associated with more rapid axial length progression.[24]

Ultraviolet-related Eye Diseases Due to Childhood Ultraviolet Radiation Damage

Cumulative UV radiation (UVR) exposure is related to numerous eye diseases in the adulthood. Periorbital skin cancers account for 5%–10% of all skin cancers.[6,25] Skin cancers, pterygium, pinguecula, ocular surface squamous neoplasia, and cortical cataracts are all related to UVR exposure. AMD has been associated with UV exposure. The Blue Mountains Eye Study showed that people who worked outdoors had a higher incidence of AMD and soft drusen.[12] The relationship between sunlight and AMD was also explored in The Beaver Dam Eye Study,[26] with findings that the amount of leisure time spent outdoors in summer was significantly associated with wet macular degeneration (odds ratio: 2.26; 95% confidence interval: 1.06–4.81). Furthermore, even after adjusting for age and time spent outdoors in summer, UV protection with sunglasses reduced the amount of retinal pigment and soft indistinct drusen.[27]

Pingueculae and pterygia are common UV-related eye diseases and have an earlier onset than other UV-related eye diseases, with a peak prevalence between 20 and 40 years of age. They are used to highlight the rate of UV-related eye disease.[28] UVR levels vary in regions depending on the latitude, altitude, sun elevation, cloud cover, and ground reflection.[29] Exposure of the population to UVR also depends on outdoor occupation, outdoor hobbies, activities, and habitual use of UV protection, such as sunglasses and hats. In addition, some genetic variations that lead to defective DNA repair after UV damage are known to predispose to pterygium and other UV-related eye diseases.[28]

UV fluorescence photography (UFP) has allowed the degree of UV damage to be quantified objectively.[30,31,32] UFP has demonstrated UV-induced damage in childhood, and there is an inverse relationship between childhood UV exposure and myopia.[33] Children have the least naturally developed protection against UVR, as 80% of UV eye exposure occurs before a child turns 18 years old.[34] Using UFP, 30% of children 9–11 years demonstrated UV damage to their eyes. By 12–15 years of age, 80% of children had damage detected using UFP, but even more alarmingly, 30% had clinically evident pinguecula or pterygium.[30] Crewe et al. showed that pterygium is an indicator of UV exposure. People with pterygium should be screened for cutaneous melanoma as they have a 24% increased risk.[35]

The prevalence of pterygium, known as UVR exposure related, varies due to a combination of outdoor activity (working or leisure), latitude and altitude [Table 1]. Hence, all these factors need to be considered simultaneously as taken in isolation any of these factors may be misleading. For example, the prevalence of pterygia in Tehran is 1.3%, and Shahroud is at 9.4%. Tehran’s latitude is 35°, and Shahroud’s is 36°. These Iranian cities have a similar altitude of 1189 m and 1345 m above sea level, respectively. The key difference is that Shahroud is an agricultural area with most women and men employed in outdoor occupations. Most employment in Tehran, by comparison, is in indoor jobs in the government sector, industrial firms, and shops.

Table 1.

Correlation of pterygium prevalence with myopia prevalence

| Region (latitude) | Prevalence of pterygia | Prevalence of myopia |

|---|---|---|

| Riau Archipelago, Indonesia (0.9°) | 17%[36] | |

| Tanjong Pagar, Singapore (1.0°) | 6.9%[37] | 38.7%[38] |

| Benin City, Nigeria (6.3°) | 12.5%[39] | 16.2%[40] |

| Sumatra, Indonesia (11.0°) | 10%[41] | 26.1%[42] |

| Lima, Peru (12.0°) | 31%[43] | |

| Barbados (13.0°) | 23% (black, of 2714) 10% (white, of 59)[44] |

12%[45] |

| South India (17.4°) | 9.5%[46] | 35.6%[47] |

| Meiktila, Myanmar (21.0°) | 19.6%[48] | 42.7%[49] |

| Botucatu City, Brazil (22.9°) | 8.12%[50] | 29.7%[51] |

| Blue Mountains, Australia (24.8°) | 7.3%[52] | 15%[53] |

| Kumejima Island, Japan (26.0°) | 30.8%[54] | 29.5%[55] |

| Qatar (26.0°) | 6.2%[56] | |

| Kathmandu Valley, Nepal (27.7°) | 12.4%[57] | 13.63%[58] |

| Amami Island, Japan (28.0°) | 25%[59] | |

| Arizona, USA (32.0°) | 16%[60] | 33.1%[61] |

| Henan County, China (34.0°) | 17.9%[62] | |

| Tehran, Iran (35.0°) | 1.3%[63] | 21.8%[64] |

| Shahroud, Iran (36.4°) | 9.4%[65] | 30.2%[66] |

| Northern Japan (36.6°) | 4.4%[67] | |

| South Korea (36.6°) | 3.8%[68] | 70.6%[69] |

| North-Western Spain (41.7°) | 5.9%[70] | 30.1%[71] |

| Copenhagen (55.7°) | 0.74%[72] | 12.8%[73] |

| Greenland (77.6°) | 8.6%[72] | 14.1%[74] |

The overall pterygium prevalence worldwide is 10.2%.[75] However, the prevalence varies from 1.3% in Tehran,[63] Iran, to 31% in Lima, Peru.[43] Similarly, pinguecula, the precursor to pterygia, varies from 11% in Southern India[46] to 56% in Greenland[72] and up to 90%[76] in the Red Sea, Jordan. The wide variation of pterygium and pingueculae prevalence cannot be accounted for by the variations in latitude or altitude alone, just as the prevalence of skin cancer cannot be entirely explained by latitude or altitude.[77]

A dose-response curve for outdoor exposure and pterygium growth has been reported.[78] Furthermore, a Chinese study of those over 50 years found that age and working outdoors with daily sunlight exposure of 2 h were the independent risk factors in developing pingueculae; the prevalence was 76%.[79] The risk of ocular surface squamous neoplasia is also associated with time outdoors.[80]

Correlation between Myopia and Ultraviolet-related Eye Disease

Myopia has a lower prevalence in areas with a higher incidence of skin cancers and UV-related diseases.[81] This result was again demonstrated by Kempen et al.,[82] who showed that areas with the highest prevalence of skin cancers had the lowest levels of myopia by using the data from the Beaver Dam, Rotterdam, the Blue Mountains Eye Studies, and the Melbourne Vision Impairment Project. The presence of pterygium has been associated with reduced axial length measurements. Only 1.8% of patients with axial lengths greater than 26 mm have pterygia compared to 51.4% of pterygia patients with axial lengths less than 23 mm in the same population group.[83]

The prevalence of myopia has been tabulated against the prevalence of pterygium [Table 1] and pinguecula [Table 2]. There is a low prevalence of myopia in several populations with a high prevalence of pterygium [Table 1]. Similarly, a high prevalence of pinguecula is seen in populations with low rates of myopia, such as Shanghai. The very high myopia rate in South Korea at 70.6%[78] inversely correlates with the 3.8% rate of pterygia.[68] In Greenland, myopia prevalence was 14.1%,[74] higher than expected compared to the pterygium prevalence of 8.6%.[72] However, the high rate of myopia could be explained by the change in education policy, which made it compulsory for all Inuit children to start formal schooling. This policy would increase the rates of myopia before causing a reduction in the prevalence of pterygium, which has a later onset. Data from Zhang et al.[86] are summarized in Table 3, showing the correlation of axial lengths against pterygium. Further studies correlating axial length with the rates of pterygium are needed to confirm that this holds true in different ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Correlation between the prevalence of pinguecula and myopia

| Region (latitude) | Prevalence of pinguecula, n (%) | Prevalence of myopia, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Benin City, Nigeria (6.3°) | 25.7%[39] | 16.2%[40] |

| South India (17.4°) | 11.3%[46] | 35.6%[47] |

| Blue Mountains, Australia (24.8°) | 69.5%[52] | 15.0%[53] |

| Red Sea, Jordan (29.4°) | 90%[76] | |

| Shanghai, China (31.2°) | 75.57%[79] | 22.9%[84] |

| Kyoto, Japan (35.0°) | 61%[85] | |

| Shahroud, Iran (36.4°) | 61%[65] | 30.2%[66] |

| North-Western Spain (41.7°) | 47.9%[70] | 30.1%[71] |

| Copenhagen (55.7°) | 41%[72] | 12.8%[73] |

| Greenland (77.6°) | 56%[72] | 14.1%[74] |

Table 3.

Axial length versus prevalence of pterygium

| Study 1: Zhang et al.[86] | Axial length ≤23 mm | Axial length ≤26 mm | Axial length >26 mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of pterygium (%) | 51.4 | 46.8 | 1.8 |

Hyperopia was associated with higher rates of choroidal neovascular membranes in AMD, hypothesized to be related to choroidal circulation.[87] Similarly, a Korean study found that for each diopter of increasing spherical equivalent of myopia there was an inversely reducing rate of any or early AMD.[88] Further research is required to understand if there is a link between maximum UV exposure experienced in childhood and maximum UV penetration, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ultraviolet light maximally penetrates the eye during childhood, reaching the retina during the youngest years of life

| Wave length (nm) | 0–2, n (%) | 2–10, n (%) | 11–20, n (%) | 21–39, n (%) | 40–59, n (%) | 60–90, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 320 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 400–450 | 70–80 | 60–70 | 60 | 50–60 | 40 | 20 |

| 450–1500 | 70–80 | 60–70 | 60–70 | 60–70 | 40–70 | 30–60 |

Optimal Ultraviolet Protection

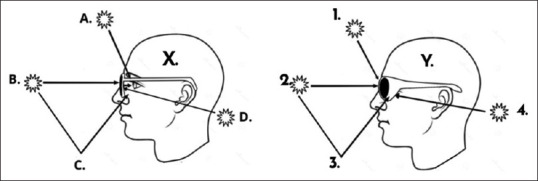

The geometry of UVR reaching the eye and periorbital skin is complicated.[89] When in motion, the human head is slightly tilted forward, and the eye position looks downward, approximately 15° below the horizontal.[90] This position means that UV light mostly reaches the eye in three ways. Direct UVR can enter the eye directly, which occurs when the sun is lower in the sky in the two hours around the sunrise and sunset[90] [Figure 1]. Direct UVR does not reach the eye during the middle of the day, as the eye is facing forward and tilts slightly downward. Reflected UVR reaches the eye from the surfaces around us. UVR reflectivity varies and is the highest at 50% from water and snow.[91] High-level cloud cover on an overcast day results in greater UV scatter from reflected light, which is even greater at higher altitudes.[46] Finally, overhead UVR reaches the eye when the sun is high in the sky in the middle of the day. This time corresponds to the peak time UV damages the skin.

Figure 1.

Typical sunglasses such as worn by person X blocks most of the direct (B) ultraviolet radiation (UVR) from entering the eye. However, the UVR still enters the eye by a combination of overhead (A) and reflected light (C). Futhermore, the UVR that comes in around the arm of the sunglasses (D) bounces off the back surface of the lens into the dilated pupil as the dark lenses have disabled the squint reflex. In person Y, the frame design limits the direct entry (2), the overhead light (1), and reflected light (3). The UVR that comes around the arm (4) is limited. Lens coatings can further limit UVR being reflected toward the eyes

The natural squint reflex reduces UVR in the eyes when outside.[92] The nondominant eyelid closes, protecting the eye, the pupils constrict, the palpebral aperture narrows, and the brow lowers in the dominant eye.[91] Bilateral diseases where UVR is important in the pathogenesis tend to occur in the dominant eye first, such as pterygium,[93] due to the lid closure on the nondominant eye.

Sunglasses should protect from UVR at least the same level as the natural squint reflex, limiting UV into the eye. However, poorly protecting sunglasses reduce the glare for the wearer and the squint reflex is relaxed. Hence, the palpebral aperture widens, the brow relaxes, and the pupils dilate.[11] This widening paradoxically allows more UVR onto the periorbital skin, ocular surface and into the eye. Furthermore, as the sunglass lens is a smooth surface, the reflected UVR reaching the back surface of the lens from around the poorly fitting frame is reflected off the lens into the eye.[27,29] This is demonstrated by the difference in the level of protection offered to the eye in Figure 1. UV detectors mounted on mannequin eyes have shown that 95%–98% UV-blocking lenses allow 18%–25% UVR to reach the cornea.[27,29] This contrasts with clear scripted lenses that block 95% UVR as wearers use their squint reflex to reduce glare.[27]

Although sunglasses reduce the lux of light reaching the eye, it is still 11 to 43 times higher than the lux indoors. This was shown in a Singaporean study that used child mannequin heads to assess the effect of different outdoor environments with sunglasses and a hat for UV protection on the lux of light reaching the eye. This light level was considered sufficient for myopia control if an outdoor activity was undertaken for at least 2 hours daily.[94] This approach can simultaneously encourage outdoor activity for myopia control and maximum UVR protection for the eye and skin.[95]

Conclusion

Animal, epidemiological, and interventional studies all indicate that increasing exposure to high lux light can limit axial length progression. The ideal duration is not conclusive but is indicated at least 2 hours per day. Whilst outdoors, children’s eyes should be shielded with UV-protective eyewear as part of all sun protection campaigns worldwide, as long-term eye health is essential in reducing the significant burden of UV-eye diseases. The push for UV protection for the eye aligns with the call to encourage children to play outside to reduce myopia. The child’s eye needs to be protected at the time of life when it has the least naturally developed defenses. With growing worldwide, concerns regarding myopia and its increasing prevalence in the next 30 years, children are encouraged to spend more time outdoors. However, these children should be outdoors with UV protection for their eyes and skin.

We need to acknowledge that different sunglasses offer different levels of eye protection. Hence, when advocating for children to spend more time outside, we must ensure that our advocated solution simultaneously reduces the incidence and progression of myopia and UV-related eye diseases. The design and grade of sunglasses offering UV protection must be clearly identifiable so parents, caregivers, and eye care professionals can make informed choices.

Shielding children’s eyes from UVR with maximally protective sunglasses whilst encouraging outdoor activity during childhood would reduce the incidence of myopia and simultaneously protect the eyes from harmful UVR. Ophthalmologists, optometrists, and all eye care professionals can lead this initiative by understanding and simultaneously minimizing the long-term impact of both epidemics.

In conclusion, the public health message regarding myopia progression in children should include the equally important message to protect their eyes from the damaging effects of UV exposure. Future studies looking at the prevalence of myopia should investigate the incidence of pterygium/pinguecula or, ideally, use UVFP to compare the prevalence of UVR diseases. This correlation will provide additional important evidence for protecting children’s eyes to reduce the incidence of UVR eye diseases 10–80 years after exposure. Future studies may also help identify the minimum lux required to retard myopia progression versus UV levels resulting in eye damage to help achieve the optimum balance to prevent both conditions simultaneously. Public health strategies will then be able to communicate clear recommendations to combat both sight-threatening epidemics.

Disclosure

As a result of their research in this area, Daya Sharma, Shanel Sharma, and Alina Zeldovich founded and hold shares in Beamers, which produces and sells protective sunglasses.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this paper.

References

- 1.Holden BA, Fricke TR, Wilson DA, Jong M, Naidoo KS, Sankaridurg P, et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1036–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The impact of Myopia and High Myopia. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flitcroft DI. The complex interactions of retinal, optical and environmental factors in myopia aetiology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:622–60. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haarman AE, Enthoven CA, Tideman JW, Tedja MS, Verhoeven VJ, Klaver CC. The complications of myopia: A review and meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61:49. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.4.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong S, Sankaridurg P, Naduvilath T, Zang J, Zou H, Zhu J, et al. Time spent in outdoor activities in relation to myopia prevention and control: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017;95:551–66. doi: 10.1111/aos.13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran JM, Phelps PO. Periocular skin cancer: Diagnosis and management. Dis Mon. 2020;66:101046. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2020.101046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee GA, Hirst LW. Retrospective study of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1997;25:269–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1997.tb01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moran DJ, Hollows FC. Pterygium and ultraviolet radiation: A positive correlation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:343–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.5.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sliney DH. Ocular injury due to light toxicity. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1988;28:246–50. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198802830-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sliney DH. Physical factors in cataractogenesis: Ambient ultraviolet radiation and temperature. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:781–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sliney DH. Ocular exposure to environmental light and ultraviolet –The impact of lid opening and sky conditions. Dev Ophthalmol. 1997;27:63–75. doi: 10.1159/000425651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schick T, Ersoy L, Lechanteur YT, Saksens NT, Hoyng CB, den Hollander AI, et al. History of sunlight exposure is a risk factor for age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2016;36:787–90. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashby R, Ohlendorf A, Schaeffel F. The effect of ambient illuminance on the development of deprivation myopia in chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5348–54. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashby RS, Schaeffel F. The effect of bright light on lens compensation in chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:5247–53. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith EL, 3rd, Hung LF, Huang J. Protective effects of high ambient lighting on the development of form-deprivation myopia in rhesus monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:421–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norton TT, Siegwart JT., Jr Light levels, refractive development, and myopia –A speculative review. Exp Eye Res. 2013;114:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P, Saw SM. Myopia, lifestyle, and schooling in students of Chinese ethnicity in Singapore and Sydney. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:527–30. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan L, Sankaridurg P, Ho A, Chen X, Lin Z, Thomas V, et al. Myopia progression in Chinese children is slower in summer than in winter. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:1196–202. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3182640996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulk GW, Cyert LA, Parker DA. Seasonal variation in myopia progression and ocular elongation. Optom Vis Sci. 2002;79:46–51. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rusnak S, Salcman V, Hecova L, Kasl Z. Myopia progression risk: Seasonal and lifestyle variations in axial length growth in Czech children. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:5076454. doi: 10.1155/2018/5076454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He M, Xiang F, Zeng Y, Mai J, Chen Q, Zhang J, et al. Effect of time spent outdoors at school on the development of myopia among children in China: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:1142–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J, Kifley A, Huynh S, Smith W, et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho CL, Wu WF, Liou YM. Dose-response relationship of outdoor exposure and myopia indicators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of various research methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2595. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16142595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Read SA, Collins MJ, Vincent SJ. Light exposure and eye growth in childhood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:6779–87. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook BE, Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:746–50. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BE. Sunlight and age-related macular degeneration. The beaver dam eye study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:514–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090040106042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sliney DH. Photoprotection of the eye –UV radiation and sunglasses. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;64:166–75. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma D. In Faculty of Medicine, Medical Sciences. Sydney, Australia: University of New South Wales; 2010. Inflammation –Associated S100 Protein in Pterygium, Tears and Uv-Irradiated Murine Corneas. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sliney DH. Geometrical assessment of ocular exposure to environmental UV radiation –Implications for ophthalmic epidemiology. J Epidemiol. 1999;9:S22–32. doi: 10.2188/jea.9.6sup_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ooi JL, Sharma NS, Papalkar D, Sharma S, Oakey M, Dawes P, et al. Ultraviolet fluorescence photography to detect early sun damage in the eyes of school-aged children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:294–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sherwin JC, McKnight CM, Hewitt AW, Griffiths LR, Coroneo MT, Mackey DA. Reliability and validity of conjunctival ultraviolet autofluorescence measurement. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:801–5. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ooi JL, Sharma NS, Sharma S, Papalkar D, Oakey M, Dawes P, et al. Ultraviolet fluorescence photography: Patterns in established pterygia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKnight CM, Sherwin JC, Yazar S, Forward H, Tan AX, Hewitt AW, et al. Myopia in young adults is inversely related to an objective marker of ocular sun exposure: The Western Australian raine cohort study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:1079–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. Protecting Children from Ultraviolet Radiation. 2009. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 24]. Available from:https://www.who.int/uv/resources/archives/fs261/en/

- 35.Crewe JM, Threlfall T, Clark A, Sanfilippo PG, Mackey DA. Pterygia are indicators of an increased risk of developing cutaneous melanomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:496–501. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan CS, Lim TH, Koh WP, Liew GC, Hoh ST, Tan CC, et al. Epidemiology of pterygium on a tropical island in the Riau Archipelago. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:908–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong TY, Foster PJ, Johnson GJ, Seah SK, Tan DT. The prevalence and risk factors for pterygium in an adult Chinese population in Singapore: The Tanjong Pagar survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:176–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00703-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong TY, Foster PJ, Hee J, Ng TP, Tielsch JM, Chew SJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for refractive errors in adult Chinese in Singapore. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2486–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ukponmwan CU, Dawodu OA, Edema OF, Okojie O. Prevalence of pterygium and pingueculum among motorcyclists in Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 2007;84:516–21. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v84i11.9570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ezelum C, Razavi H, Sivasubramaniam S, Gilbert CE, Murthy GV, Entekume G, et al. Refractive error in Nigerian adults: Prevalence, type, and spectacle coverage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5449–56. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gazzard G, Saw SM, Farook M, Koh D, Widjaja D, Chia SE, et al. Pterygium in Indonesia: Prevalence, severity and risk factors. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1341–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saw SM, Gazzard G, Koh D, Farook M, Widjaja D, Lee J, et al. Prevalence rates of refractive errors in Sumatra, Indonesia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3174–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rojas JR, Málaga H. Pterygium in Lima, Peru. Ann Ophthalmol. 1986;18:147–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luthra R, Nemesure BB, Wu SY, Xie SH, Leske MC Barbados Eye Studies Group. Frequency and risk factors for pterygium in the Barbados eye study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1827–32. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.12.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu SY, Yoo YJ, Nemesure B, Hennis A, Leske MC Barbados Eye Studies Group. Nine-year refractive changes in the Barbados eye studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4032–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asokan R, Venkatasubbu RS, Velumuri L, Lingam V, George R. Prevalence and associated factors for pterygium and pinguecula in a South Indian population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:39–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Joseph S, Krishnan T, Ravindran RD, Maraini G, Camparini M, Chakravarthy U, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for myopia and other refractive errors in an adult population in Southern India. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2018;38:346–58. doi: 10.1111/opo.12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Durkin SR, Abhary S, Newland HS, Selva D, Aung T, Casson RJ. The prevalence, severity and risk factors for pterygium in central Myanmar: The Meiktila eye study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:25–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.119842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta A, Casson RJ, Newland HS, Muecke J, Landers J, Selva D, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in rural Myanmar: The Meiktila eye study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shiratori CA, Barros JC, Lourenço Rde M, Padovani CR, Cordeiro R, Schellini SA. Prevalence of pterygium in Botucatu city –São Paulo state, Brazil. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2010;73:343–5. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492010000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schellini SA, Durkin SR, Hoyama E, Hirai F, Cordeiro R, Casson RJ, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in a Brazilian population: The Botucatu eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16:90–7. doi: 10.1080/09286580902737524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Panchapakesan J, Hourihan F, Mitchell P. Prevalence of pterygium and pinguecula: The Blue Mountains eye study. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1998;26(Suppl 1):S2–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1998.tb01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Attebo K, Ivers RQ, Mitchell P. Refractive errors in an older population: The Blue Mountains eye study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1066–72. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90251-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiroma H, Higa A, Sawaguchi S, Iwase A, Tomidokoro A, Amano S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of pterygium in a Southwestern island of Japan: The Kumejima study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:766–71.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakamura Y, Nakamura Y, Higa A, Sawaguchi S, Tomidokoro A, Iwase A, et al. Refractive errors in an elderly rural Japanese population: The Kumejima study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hosni FA. Pterygium in Qatar. Ophthalmologica. 1977;174:81–7. doi: 10.1159/000308582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shrestha S, Shrestha SM. Comparative study of prevalence of pterygium at high altitude and Kathmandu Valley. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2014;12:187–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karki KJ, Karki M. Refractive error profile –A clinical study. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2004;2:208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sasaki H, Asano K, Kojima M, Sakamoto Y, Kasuga T, Nagata M, et al. Epidemiological survey of ocular diseases in K Island, Amami Islands: Prevalence of cataract and pterygium. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1999;103:556–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.West S, Muñoz B. Prevalence of pterygium in Latinos: Proyecto VER. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1287–90. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.152694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vitale S, Ellwein L, Cotch MF, Ferris FL, 3rd, Sperduto R. Prevalence of refractive error in the United States, 1999-2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1111–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.8.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu J, Wang Z, Lu P, Chen X, Zhang W, Shi K, et al. Pterygium in an aged Mongolian population: A population-based study in China. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:421–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6703005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. Prevalence and risk factors of pterygium and pinguecula: The Tehran eye study. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1125–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Mohammad K. The age- and gender-specific prevalences of refractive errors in Tehran: The Tehran eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11:213–25. doi: 10.1080/09286580490514513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rezvan F, Hashemi H, Emamian MH, Kheirkhah A, Shariati M, Khabazkhoob M, et al. The prevalence and determinants of pterygium and pinguecula in an urban population in Shahroud, Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50:689–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Jafarzadehpur E, Yekta AA, Emamian MH, Shariati M, et al. High prevalence of myopia in an adult population, Shahroud, Iran. Optom Vis Sci. 2012;89:993–9. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31825e6554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tano T, Ono K, Hiratsuka Y, Otani K, Sekiguchi M, Konno S, et al. Prevalence of pterygium in a population in Northern Japan: The locomotive syndrome and health outcome in Aizu cohort study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91:e232–6. doi: 10.1111/aos.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rim TH, Kang MJ, Choi M, Seo KY, Kim SS. The incidence and prevalence of pterygium in South Korea: A 10-year population-based Korean cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han SB, Jang J, Yang HK, Hwang JM, Park SK. Prevalence and risk factors of myopia in adult Korean population: Korea national health and nutrition examination survey 2013-2014 (KNHANES VI) PLoS One. 2019;14:e0211204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Viso E, Gude F, Rodríguez-Ares MT. Prevalence of pinguecula and pterygium in a general population in Spain. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:350–7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Montes-Micó R, Ferrer-Blasco T. Distribution of refractive errors in Spain. Doc Ophthalmol. 2000;101:25–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1002762724601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Norn MS. Prevalence of pinguecula in Greenland and in Copenhagen, and its relation to pterygium and spheroid degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1979;57:96–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1979.tb06664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jacobsen N, Jensen H, Goldschmidt E. Prevalence of myopia in Danish conscripts. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007;85:165–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alsbirk PH. Refraction in adult West Greenland Eskimos. A population study of spherical refractive errors, including oculometric and familial correlations. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1979;57:84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1979.tb06663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu T, Liu Y, Xie L, He X, Bai J. Progress in the pathogenesis of pterygium. Curr Eye Res. 2013;38:1191–7. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2013.823212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Norn MS. Spheroid degeneration, pinguecula, and pterygium among Arabs in the Red Sea territory, Jordan. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982;60:949–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Crombie IK. Variation of melanoma incidence with latitude in North America and Europe. Br J Cancer. 1979;40:774–81. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1979.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Threlfall TJ, English DR. Sun exposure and pterygium of the eye: A dose-response curve. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:280–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00161-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Le Q, Xiang J, Cui X, Zhou X, Xu J. Prevalence and associated factors of pinguecula in a rural population in Shanghai, Eastern China. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:130–8. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1012269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Waddell K, Kwehangana J, Johnston WT, Lucas S, Newton R. A case-control study of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) in Uganda. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:427–32. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Franchina M, Yazar S, Hunter M, Gajdatsy A, deSousa JL, Hewitt AW, et al. Myopia and skin cancer are inversely correlated: Results of the Busselton healthy ageing study. Med J Aust. 2014;200:521–2. doi: 10.5694/mja14.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kempen JH, Mitchell P, Lee KE, Tielsch JM, Broman AT, Taylor HR, et al. The prevalence of refractive errors among adults in the United States, Western Europe, and Australia. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:495–505. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pan CW, Shi B, Zhong H, Li J, Chen Q. The impact of parental rural-to-urban migration on children's refractive error in rural China: A propensity score matching analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2020;27:39–44. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2019.1678656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu L, Li J, Cui T, Hu A, Fan G, Zhang R, et al. Refractive error in urban and rural adult Chinese in Beijing. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Norn M. Spheroid degeneration, keratopathy, pinguecula, and pterygium in Japan (Kyoto) Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1984;62:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1984.tb06756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang LM, Lu Y, Gong L. Pterygium is related to short axial length. Cornea. 2020;39:140–5. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Böker T, Fang T, Steinmetz R. Refractive error and choroidal perfusion characteristics in patients with choroidal neovascularization and age-related macular degeneration. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1993;2:10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lin SC, Singh K, Chao DL, Lin SC. Refractive error and the risk of age-related macular degeneration in the South Korean population. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2016;5:115–21. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sliney DH. Exposure geometry and spectral environment determine photobiological effects on the human eye. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:483–9. doi: 10.1562/2005-02-14-RA-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sasaki H, Sakamoto Y, Schnider C, Fujita N, Hatsusaka N, Sliney DH, et al. UV-B exposure to the eye depending on solar altitude. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37:191–5. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31821fbf29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sliney DH. Geometrical gradients in the distribution of temperature and absorbed ultraviolet radiation in ocular tissues. Dev Ophthalmol. 2002;35:40–59. doi: 10.1159/000060809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sliney DH. How light reaches the eye and its components. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21:501–9. doi: 10.1080/10915810290169927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jensen OL. Pterygium, the dominant eye and the habit of closing one eye in sunlight. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1982;60:568–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1982.tb00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lanca C, Teo A, Vivagandan A, Htoon HM, Najjar RP, Spiegel DP, et al. The effects of different outdoor environments, sunglasses and hats on light levels: Implications for myopia prevention. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2019;8:7. doi: 10.1167/tvst.8.4.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Karouta C, Ashby RS. Correlation between light levels and the development of deprivation myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;56:299–309. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.