Abstract

Objective.

This study investigates the potential of cloud-based serverless computing to accelerate Monte Carlo (MC) simulations for nuclear medicine imaging tasks. MC simulations can pose a high computational burden – even when executed on modern multi-core computing servers. Cloud computing allows simulation tasks to be highly parallelized and considerably accelerated.

Approach.

We investigate the computational performance of a cloud-based serverless MC simulation of radioactive decays for positron emission tomography imaging using Amazon Web Service (AWS) Lambda serverless computing platform for the first time in scientific literature. We provide a comparison of the computational performance of AWS to a modern on-premises multi-thread reconstruction server by measuring the execution times of the processes using between 105 and 2 · 1010 simulated decays. We deployed two popular MC simulation frameworks – SimSET and GATE – within the AWS computing environment. Containerized application images were used as a basis for an AWS Lambda function, and local (non-cloud) scripts were used to orchestrate the deployment of simulations. The task was broken down into smaller parallel runs, and launched on concurrently running AWS Lambda instances, and the results were postprocessed and downloaded via the Simple Storage Service.

Main results.

Our implementation of cloud-based MC simulations with SimSET outperforms local server-based computations by more than an order of magnitude. However, the GATE implementation creates more and larger output file sizes and reveals that the internet connection speed can become the primary bottleneck for data transfers. Simulating 109 decays using SimSET is possible within 5 min and accrues computation costs of about $10 on AWS, whereas GATE would have to run in batches for more than 100 min at considerably higher costs.

Significance.

Adopting cloud-based serverless computing architecture in medical imaging research facilities can considerably improve processing times and overall workflow efficiency, with future research exploring additional enhancements through optimized configurations and computational methods.

Keywords: Cloud-based computing, Monte-Carlo simulation, AWS Lambda, SimSET, GATE, Nuclear Medicine Imaging, computational efficiency

1. Introduction

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is a provider of cloud computing resources which includes storage (S3, “Simple Storage Service”), server-based provisioned computing (EC2, “Elastic Cloud Compute”), and serverless non-provisioned computing (Lambda) [1]. AWS and other cloud providers (Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud, among others) offer a myriad of services, which can address many computational burdens commonly encountered in research. EC2 is comparable to an off-site virtual machine, where a researcher can request a combination of computer processing units (CPUs), random-access memory (RAM), network speed, storage, graphical processing units (GPUs), and even field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), and is billed whenever the machine is in use. AWS Lambda, by contrast, allows a researcher to define a platform-agnostic function that is executed in isolation and billed by runtime and memory [2]. This enables parallel execution of functions with short-duration execution time without the need for provisioning or managing servers. The functions may be ‘just code’, such as python functions, or fully containerized applications which perform more complex operations. Lambda as a serverless computing tool integrates with other AWS services such as Amazon Simple Storage Service (S3) enabling developers to build complex distributed systems that can process data from different sources. With AWS Lambda, developers can focus on the computational code rather than managing infrastructure required for large scale parallel distributed computing.

Monte Carlo (MC) simulation is a common task in engineering and physics research with numerous applications in nuclear medical imaging, and it is well suited for deployment on AWS or other cloud frameworks. Instances of MC simulations can be run in parallel and combined to improve the statistical accuracy of the result. When run with on-premises servers, simulation jobs can easily saturate the resources available to researchers, and simulations can last weeks or more. With AWS EC2 instances such computation can be run efficiently [3, 4]. AWS Lambda serverless computing infrastructure further improves distributed cloud-based computing to maximize performance and scale while minimizing costs. Simulation jobs can be divided into batches of up to 1000 parallel tasks currently, exceeding what is typically possible with on-premises servers. AWS Lambda also further reduces the computational architecture complexity and cost compared to AWS EC2. Billing varies by service, but typically scales with the requested computing resources and duration of execution and may be comparable to the total amortized cost of an on-premises server. Moreover, computing tasks are often project-based and highly variable, which can lead to slow-down especially in multi-user settings.

MC methods play an important role in nuclear medical imaging where they have been effectively applied to model processes or random behavior and to quantify physical parameters, which often are challenging or impossible to estimate through experimental measurements or calculations. Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) represent common applications for these MC modeling techniques, given the inherent stochastic nature of radiation emission, transport, and detection processes associated with these imaging technologies [5]. Predominantly, PET and SPECT research laboratories utilize MC simulations to evaluate reconstruction and correction techniques and to investigate specific facets of the imaging system response [6]. Moreover, this method also finds application in the development and evaluation of imaging devices, as well as in data correction during their operational phase.

To provide a realistic use-case scenario for MC simulations in nuclear medical imaging we will present the application of MC methods to the simulation of the detector response of the uEXPLORER total-body PET scanner. This novel imaging modality requires fast and efficient data correction methods, for example scatter correction (SC). Typically, the clinical requirement for reconstructions of 3D total-body images is real-time, hence research into increasing the speed and reducing the cost is of paramount importance. In the context of PET scanning, MC simulations are used to develop and optimize reconstruction or data correction algorithms – thereby enhancing image quality and accuracy (e.g., [7, 8]) – or to evaluate novel detectors and assess their performance (e.g., [9]), and are furthermore utilized to explore alternative detector geometries like sparse scanner designs [10]. Using serverless cloud-based computation we aim to improve computation time by an order of magnitude. We are presenting implementations using the examples of two different commonly used MC simulation tools: Simulation System for Emission Tomography (SimSET) [11] and Geant4 Application for Tomographic Emission (GATE) [12].

SimSET has previously been used to develop image reconstruction methods and was in the scope of this study utilized for SC [8]. Introduced as an alternative to widely utilized direct analytical calculation of scatter [13], MC-based SC has proven to be reliable and accurate, however exhibits considerable computational challenges [14]. This becomes particularly important for large axial field of view (FOV) and total-body PET, where the extensive number of lines of response and increased acceptance angles introduce additional computational difficulties [15].

Like SimSET, GATE can be used to perform MC simulations of different imaging systems like PET, SPECT, CT scanners, or other nuclear medicine imaging modalities. Further applications include dosimetry calculations [16], studies with various radioactive tracers [17], proton range monitoring in particle therapy treatment [18], as well as the design and optimization of imaging techniques (e.g., [19]). GATE also provides extensions for performing certain types of optical simulations relevant to the development of scintillation detectors, such as modeling crystal surface treatments and non-scintillation photoemission, like Cherenkov [20]. Generating statistically significant results in any of these domains requires simulating sufficient radioactive decays, which can be a great computational challenge for certain tasks.

We implemented a framework that facilitated MC computation of radioactive decays using both SimSET and GATE on AWS Lambda. We evaluated the performance of both implementations when executed on our on-premises reconstruction servers in comparison to the serverless implementation on AWS Lambda.

2. Method

a. Serverless Cloud-based Monte Carlo simulations

Implementation using SimSET

We previously implemented a scatter correction (SC) method in the UC Davis in-house iterative PET image reconstruction framework for data acquired on the uEXPLORER total-body PET scanner [8, 21]. The previous implementation employed parallel simulations of 2.5 · 109 radioactive decays of 18F on multi-core CPUs on our on-premises reconstruction server, which took about one hour of computation time per iteration. Consequently, this approach proved to be impractical for routine clinical PET image reconstruction. Further reduction of processing times with the same algorithm would require more servers on site, leading to additional procurement and maintenance costs. As an alternative we explored deploying SimSET in a cloud-based serverless infrastructure using AWS Lambda.

The SimSET code is well-suited for large-scale distributed parallel computing, as simulation jobs can run on independent threads on servers with multi-core CPUs and – if required – have their results merged upon completion. SimSET source code can be recompiled on any Linux operating system (OS). AWS Lambda supports custom Linux Docker container images with software that performs proprietary computation. We therefore created a Docker container image with a SimSET installation that was recompiled for the freely available Ubuntu-like OS, Amazon Linux, used by Lambda containers.

The architecture of the serverless cloud-based implementation of SC with SimSET is depicted in Figure 1. SimSET requires a set of parameter files for material and detector definition, an activity distribution map (here, a PET image from a previous image reconstruction iteration), and an attenuation map of the object in the PET scanner. A Bash shell script was developed to upload these configuration files to AWS S3 (approximately 310 MB in our case) and then utilize the AWS Command Line (CLI) toolkit to trigger the invocation of Lambda instances. The execution progress of a Lambda instance can be monitored directly as data is written to AWS S3. AWS currently allows the concurrent launch of 1000 Lambda instances by default, although this can occasionally lead to throttling depending on the status of the broader AWS Lambda ecosystem. Thus, an architectural decision was made to launch 100 batches of 10 instances every 500 milliseconds to asynchronously run concurrently, which significantly reduces management of parallel computing nodes challenges faced in earlier implementations. The Lambda instances were configured with 2048 MB of memory, 1024 MB of storage and a 10-min execution timeout.

Figure 1:

The computing architecture implements an interface between the remote client, the cloud storage service (AWS S3) and the computing units (AWS lambda) to execute parallel SimSET simulations.

Upon completion of the simulation tasks, a separate AWS Lambda instance with 8128 MB memory and 10240 MB storage merges the computation results from all instances and stores them to AWS S3, from where they are automatically downloaded to the client side by the Bash shell script. E.g., a file containing 100 million simulated coincident events has a size of 1 GB. Our Lambda and S3 based distributed computing implementation resembles the map-reduce architecture [22] that can offer substantial scale and cost benefits over earlier cloud-based parallel computing work [3, 4, 23].

The output of the SimSET simulations are list-mode files of true and scattered events. For further use in our in-house image reconstruction framework, these files are subsequently processed to calculate SC factors for the next reconstruction iteration. During typical PET image reconstructions, several iterations of MC-based SC might be required, leading to repeated cloud-based computation processes. At the EXPLORER molecular imaging center (EMIC) at UC Davis, where this method was implemented, an internet connection speed of 10-GiBit/s is available for the required up- and downloads.

SimSET allows simulation of the radioactive decay of the radioisotope 18F and the propagation of the created 511-keV photons through the object in the PET FOV. Current AWS Lambda infrastructure allows one instance to compute 5 million decays without exceeding its current per-instance memory, storage, and execution time constraints [2]. This maximum number of decays is specific to our implementation and depends on scanner geometry, voxel size of the activity and attenuation map, size of the SimSET material tables, and the SimSET start-up time to load all necessary tables during execution.

Implementation using GATE

GATE is a modular, adaptable, and scripted Monte Carlo-simulation toolkit for the field of nuclear medicine [24]. It is based on the programming libraries of Geant4 – a particle tracking simulation toolbox used in particle physics and detector development. We have investigated the deployment to AWS of a ‘typical’ GATE use case for simulation of a preclinical PET scanner. Our simulation geometry targeted scanning a point source over the system field-of-view to generate the point-spread-function (PSF) response of the system, for use in PSF correction during reconstruction. However, this approach should scale equally well to any use of GATE where jobs can be easily broken into parallel components.

The implementation of GATE on Lambda was similar to that of SimSET and is shown in Figure 2. A local python script is first used to zip and upload the relevant GATE macro files (which define scanner and activity geometries) to S3. The python script then launches the necessary number of GATE jobs on Lambda, which was configure with 10240 MB or memory and 10240 MB of temporary storage. The script provides unique parameters to each instance, which can be used to invoke GATE to perform simulations which cover the desired parameter space – e.g., scanning a point source across the FOV. The number of simulated decays is distributed over NJ = 1,000 jobs, each of which equals one invocation of GATE with the given parameters simulating at least Nmin = 10,000 decays. Below a total of Nmin · NJ = 107 simulated decays, the number of jobs NJ was adjusted keeping the number of decays per job constant, because it was found to be more efficient to simulate fewer runs with more counts due to the GATE startup time. Above that threshold, the decays were equally distributed over NJ = 1,000 instances. Upon completion of the simulation, the Lambda function uploads its results to S3, where they are then downloaded by the local python script. Each invocation of the GATE simulation creates a folder with a list-mode file of true and scattered events in a Ttree object – readable by the analysis toolkit ROOT. For the GATE simulation, no concatenation of the output results on AWS was implemented.

Figure 2:

On client side a Python script is used to access the remote cloud storage service (AWS S3) and to execute GATE on parallel computing units (AWS lambda).

Implementation on on-premises servers

For performance comparison, we implemented both SimSET and GATE on our local PET image reconstruction server at the EMIC. Forty-four instances were executed in parallel on four Intel® Xeon® Gold 6126 CPUs with 12 cores at 2.6 GHz. In the case of SimSET the data were concatenated, similar to the process on AWS, while for GATE the raw output data were not further processed.

b. Performance Evaluation

The duration of generating list mode files containing true and scattered events using MC methods was recorded when utilizing both the described AWS framework and our local servers. For AWS computations, upload and download times were included in the run time measurements. We conducted simulations with varying numbers of simulated decays, ranging from 105 to 109 for GATE and up to 2 · 1010 in the case of SimSET, running on AWS Lambdas and on the on-premises server, respectively. In the case of GATE, higher computation times were observed, and the upper range had to be limited to 109 decays. Since the creation of the required configuration files and the attenuation and activity maps were performed offline in both cases, their duration was not included in runtime measurements. In case of SimSET, for more than 5 · 109 decays, the AWS process had to be invoked several times sequentially, due to the maximum execution time limitation imposed by AWS Lambda. For GATE the maximum execution time was already reached at 109 simulated decays, and larger numbers were not simulated in this case. On our local servers, the invoked processes could run without any timeout limitations.

The internet connection speed can be a considerable factor influencing the execution time of the whole process. To fully evaluate the performance of the cloud-based computation process we also recorded the run time of the computation that took place on AWS only, hereby excluding the upload and download times.

c. Cost Estimation

Building and maintaining an on-premises computational infrastructure is connected with considerable costs. Using the example of the PET image reconstruction server at the EMIC installed in 2019, the average procurement cost per computational node with four Intel® Xeon® Gold 6126 CPUs was between $130,000 and $180,000, which includes building costs for electricity, power supply and HVAC system, as well as the design of the infrastructure and network equipment. The annual expenses for maintenance and power supply are approximately $10,000. These costs are only mildly impacted by the actual server workload.

On AWS, the price per unit time and used storage and memory can be calculated [25]. Running SimSET on 1000 Lambdas while utilizing the maximum execution time of 10 min accrues $20.01, which allows for a simulation of about 4 · 109 decays. Merging the output files costs $0.08 and the data transfer to and from S3 costs $0.24. The last two values are subject to the size of the simulation data and are given for the example of simulating 109 decays. Running GATE with a maximum execution time of 15 min on 1000 Lambdas as configured above, costs $50.09, which is more than for SimSET mostly due to the larger memory and storage requirements for GATE.

3. Results

Implementation using SimSET

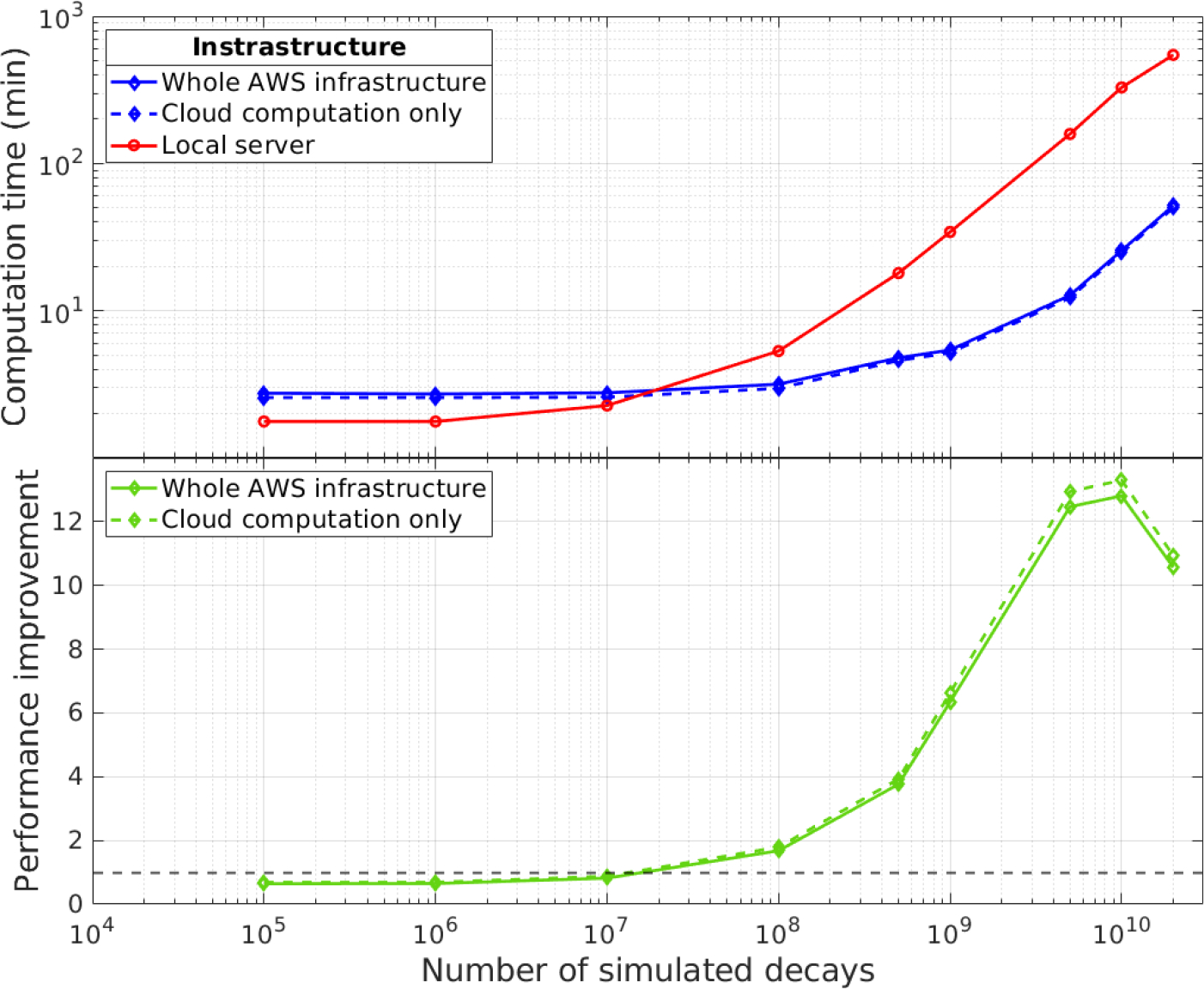

Figure 3 displays the computation time for the entire SimSET simulation process with varying numbers of simulated events, comparing the AWS-based computation (blue diamonds) and our local server (red circles). The blue dashed line shows the execution time for the process running on AWS only – not including upload and download times. For smaller numbers of simulated decays, the local server exhibits shorter computation times due to longer start-up times on AWS for creating the Lambda instances and invoking the SimSET processes. Additionally, there is data transfer between Lambda and S3, which adds to the total run time of the cloud-based implementation. However, when simulating 108 decays or more and running 1000 Lambda instances in parallel, the cloud-based serverless simulation method outperforms our local server, despite the data transfer overhead over the network. At 108 decays the AWS implementation is a factor of about 1.7 faster than the local server, as indicated by the bottom half of the graph displaying the performance improvement factor. The improvement constantly increases to a factor of 12.5 when 5· 109 decays are simulated. This improvement peaks at 1010 decays, where the computation on our local server took 158.6 min, while the AWS implementation finished within 12.7 min, thus, performing 12.8 times faster. For 2 · 1010 simulated decays, the performance improvement starts to decrease, and the AWS computation performs only 10.6 times faster than the local implementation. The decline in performance improvement is attributed to the need for sequential repetition of the Lambda process for more than 109 decays, due to the maximum execution time constraints of Lambda instances. This repetition introduces additional SimSET start-up processes and file concatenation steps. Both download times and output file sizes increase with the number of simulated decays.

Figure 3:

Comparison of the performance of SimSET simulations using cloud-based computing with AWS lambda (diamonds) to our local multi-core server (circles). The dashed line describes the computation time on the cloud only, and the bottom graph displays the performance improvement factor when using AWS compared to local computations.

Although not clearly visible in logarithmic scale, the time difference between the whole process (blue solid line) and the part only executed on AWS (black dashed line) increases from a few seconds at 105 decays to almost 2 minutes at 2 · 1010 decays, which can be attributed to the increasing size of the list-mode files to be downloaded.

Implementation using GATE

Figure 4 shows the computation times for the GATE simulations for different numbers of decays. Again, AWS-based computation (blue diamonds) is compared to our local servers (red circles). The most important observation is that in general the AWS implementation cannot outperform the local executions, except for at a very low number of 105 decays. The performance improvement factor (see solid line in the bottom half of Figure 4) is smaller than 1 for almost the entire range. The greatest bottleneck for the GATE implementation was the download of the output files, which were larger than the SimSET list-mode files and their number can be considerably larger as well depending on the number of simulated decays: above 107 decays, 1000 runs were executed each producing an output folder on S3 containing 2 files to be downloaded. Therefore, for 109 simulated decays for instance the GATE simulations on AWS finished within 54 min, however the download process extended the total run time to 133 min – thus clearly exceeding the local computations of 77 min.

Figure 4:

Comparison of the performance of GATE simulations using cloud-based computing with AWS lambda (diamonds) with our local multi-core server (circles). The dashed line describes the computation time on the cloud only, and the bottom graph displays the performance improvement factor when using AWS compared to local computations.

On the other hand, considering only the execution times on AWS and disregarding the download and upload times, serverless computation of GATE simulations is clearly faster for a large range of simulated decays. Below 3.2 · 106 simulated decays cloud-based computation is faster by up to a factor of 3, however this factor decreases for increasing number of decays, and reaching a minimum at 107 decays. The job dispatching on AWS was changed at that point as described in section 2a, which caused the performance to improve again outperforming local computations at above 3.2 · 107.

4. Discussion

Using SimSET, our findings indicate that leveraging cloud-based serverless computing resources can lead to performance improvements of more than one order of magnitude when compared to on-premises server-based computations in our specific implementations and server architecture. Since cloud-based conversion and concatenation of the SimSET output files was performed, the download times to our local computer did not cause considerable overhead and did not exceed 2 min even for 2 · 1010 simulated decays. This AWS-based SimSET implementation is therefore very well suited for frequent utilization in our in-house research PET image reconstruction pipeline: here, SimSET is used for SC, where 2.5 · 109 simulated decays per iteration proved sufficient [8]. For this number an improvement factor of approximately 11 was obtained compared to computation on our local servers.

The serverless GATE implementation on the other hand showed considerably less performance improvement compared to local computations. One bottleneck is the extensive download time for the created output files. Without any cloud-based file concatenation, compression, or pre-analysis to reduce the file sizes, the file transfer overhead will render the serverless approach computationally unfeasible. Cloud-based post-processing steps could involve containerized environments executed on a separate lambda instance allowing to run ROOT and to store all list-mode events in one ROOT TTree instance, thus reducing the file number. This would extend the execution time on AWS but might subsequently allow for considerably faster file transfers. Since GATE file sizes are so large, special care must be taken to allocate enough memory for these conversion processes, or other alternative virtual environments on AWS must be chosen.

The serverless implementation of GATE might further benefit from an optimization of the job dispatcher. While the performance clearly improved above 107 simulated decays due to the change in job handling (see Methods section a), this method of distributing the number of simulated decays over the individual GATE instances is subject to further investigation.

It should be noted that for both SimSET and GATE the geometry and distribution of the radioactive source in the field-of-view or the phantom size had no noticeable impact on the total computation time. However, other parameters considerably affected computation times, such as the size and number of voxels for the input image for the simulations, and the number of detectors (or channels) to be simulated. Particularly in frequent clinical or research nuclear medicine applications, these simulation parameters require thorough optimization to preserve accuracy. Using SimSET, approximately $10 is incurred for the simulation of 109 decays taking about 5 min., given the individual Lambda configurations and execution time constraints. Considering procurement and maintenance costs of state-of-the-art computing servers (see section 2c), serverless SC could offer a more cost-effective alternative to an on-premises SimSET execution. The average funds per node that are required for procurement and initial installation of an on-premises server infrastructure, between 13,000 and 18,000 SimSET simulations with 109 decays could be performed – that equals between 65,000 min (45.1 days) and 90,000 min (62.5 days) of non-stop computation on AWS. That amount of computation would take more than 6 times longer on the on-premises servers. Since GATE in our current implementation does not bring any computational benefits, it was excluded from the cost comparison between cloud-based and on-premises computation.

Further enhancements could be made by employing different virtual machine configurations on AWS to enable longer runtimes and concurrent processing of more events. Lambda instances do not allow control over CPU parameters. As such neither SimSET nor GATE can benefit from CPU based optimization methods. While this simplifies deployment of advanced computing software in such an architecture, it can have performance implications not observed with EC2 or local server-based approaches. It is also important to note that the performance of the AWS Lambda stack is contingent on the impact of internet connection speed and the network traffic conditions, governing upload and download speeds of data files. This has been observed to be the primary bottleneck for this implementation. This was especially problematic for the GATE implementation where in our current implementation demonstrated no real improvement compared to local servers. Even though one might be able to shorten download times with aforementioned post-processing methods executed on AWS, it might be more feasible to not download the files from S3 to the local computers in the first place and instead to implement the entire processing and analysis chain on the cloud. Depending on the task and the purpose of the GATE simulations and depending on the required memory, storage and execution time constraints, alternative virtual machines or computing instances within the AWS ecosystem would have to be chosen like the Fargate container service, EC2 instances or AWS batch computing workloads. However, some of these alternatives require manual server provisioning or scaling configurations for handling varying workloads, which has been explored in earlier cloud-based parallel computing implementations.

One limitation of performing MC simulation on cloud services like AWS is handling potentially large volumes of data, which can reach tens of GB or greater. For S3, data is billed both for storage duration as well as outbound transfers, which may be both expensive and slow in certain circumstances. These concerns can be partially mitigated by performing subsequent analysis of list-mode simulation data on other cloud services, like EC2. For example, if the only necessary simulation outputs are sinograms, rather than list-mode data, then outbound transfer costs are low and fixed even for very large simulations, and sinograms can be generated entirely within the AWS platform. However, while MC simulation software can easily be packaged into a Lambda function for reuse in many cases (simulation of different systems or geometries), subsequent analyses are often one-off or exploratory, and is less amenable to use as a Lambda function or use on the cloud.

Adoption of cloud computing in PET scanner facilities might help implement fast MC-based SC for conventional and total-body PET scanners, leading to substantial improvements in processing times and overall efficiency. This is particularly relevant as other means of acceleration via the use of GPUs are generally not available for either GATE or SimSET, underlining the importance and benefits of cloud-based MC simulations for medical imaging. While the latter has always only provided a single-threaded implementation and has not been executed on GPUs yet, specific GPU codes for GATE have been developed for different medical applications [26]. Although an acceleration factor of 60 was achieved for PET applications, the GPU code only managed the particle tracking inside the emitting object, while photon tracking, and detector response were still modeled on CPUs. Garcia et al. (2016) have implemented a GPU-based MC tool using libraries of the particle simulation tool Geant4, however it was very specialized for Single Photon Computed Tomography (SPECT), not for PET [27]. Despite considerable acceleration of the simulation times, clinically realistic whole-body planar images still took one whole day to finish. Another open project of bringing GATE to GPUs has recently been discontinued (see [28]), and, to this day, a generic use of GATE on GPUs is not available.

Despite the lack of GPU-accelerated simulations for either SimSET or GATE, there are GPU-based tools that have recently been developed for various nuclear medicine imaging applications with promising improvements in computation times: the programs gPET [29] and UMC-PET [30](Galve 2024) provide efficient MC simulations for PET, and ARCHER-NM [31](Peng 2022) enables radiation dose calculations in organs of PET/CT patients. These tools have so far only been evaluated in phantom studies and validated again other MC-based software, but might provide alternatives where the use of SimSET or GATE is not specifically required. However, the potential application to SC for dynamic PET scans, requiring individual SC for 50–100 frames due to changing activity distributions, raises questions about the time-advantages shown in Figure 3 and motivates further research. So far, MC-based SC appears to be more computationally demanding for dynamic scans compared to static clinical scans and frequent uploads and downloads (while simulating fairly small amounts of events in each invocation) might prove to be unfeasible.

While local computations typically do not expose any patient relevant data to any public network, computation on AWS bears the risk of data breach. However, this risk is minimal, as multi-factor authentication is required to access the data stored on AWS S3, and even for joint group accounts, every user needs their individual credentials. Furthermore, no patient identifying information is uploaded, but only binary files of attenuation and activity maps with no further information on how to open and read these files. In the future, the risk of accidentally revealing patient information could be further reduced in a clinical environment by applying facial anonymization tools. Such anonymization methods have been proven successful in eliminating privacy concerns in Total-Body PET/CT without loss of quantitative accuracy in the reconstructed images [32]. For clinical use of this cloud-based infrastructure, such anonymization tools could be applied prior to uploading images data to the cloud.

5. Conclusion

In this work we have implemented serverless, cloud-based Monte Carlo simulations with SimSET and GATE, which are an essential part of research into and development of imaging modalities in nuclear medicine. Adopting cloud-based computing in PET imaging and research facilities can considerably improve processing times and overall workflow efficiency, while keeping the costs manageable compared to procurement and maintenance costs of a larger local server infrastructure. The scale and implementation simplicity of serverless Lambda makes it very promising not just for SimSET and GATE but many other advanced computing packages that can be massively parallelized at very low cost. Our future research will explore additional enhancements through optimized parameter configurations in the individual simulation tools, as well as in the specific cloud-based implementation on AWS.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by NIH grant R01 CA206187, which is supported by NCI, NIBIB and the Office of the Director, and by R01 CA249422.

References

- [1].Amazon Web Services, Inc., “AWS Documentation,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/index.html. [Accessed 10 July 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- [2].I. Amazon Web Services, “AWS Lambda Serverless computing,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://aws.amazon.com/lambda. [Accessed 25 05 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ziegenhein P, Kozin I, Kamerling C and Oelfke U, “Towards real-time photon Monte Carlo dose calculation in the cloud,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 62, no. 11, pp. 43–75, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang H, Ma Y, Pratx G and Xing L, “Toward real-time Monte Carlo simulation using a commercial cloud computing infrastructure,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 56, no. 17, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zaidi H, “Relevance of accurate Monte Carlo modeling in nuclear medical imaging,” Medical physics, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 574–608, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Steven S and Buvat I, “Monte carlo simulations in nuclear medicine imaging,” in Advances in Biomedical Engineering, Elsevier, 2009, pp. 177–209. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang X, Cherry SR, Badawi RD, Qi J, “Quantitative image reconstruction for total-body PET imaging using the 2-meter long EXPLORER scanner,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 62, no. 6, p. 2465, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bayerlein R, Spencer B, Leung E, Omidvari N, Abdelhafez Y, Wang Q, Nardo L, Cherry S and Badawi R, “Development of a Monte Carlo-based scatter correction method for total-body PET using the uEXPLORER PET/CT scanner,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 69, no. 4, 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Moskal P, et al. , “Simulating NEMA characteristics of the modular total-body J-PET scanner - an economic total-body PET from plastic scintillators,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 66, p. 1750 15, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Karakatsanis N, et al. , “Physical performance of adaptive axial FOV PET scanners with a sparse detector block rings or a checkerboard configuration,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 67, no. 10, p. 105010, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lewellen, et al. , “The SimSET Program,” in Monte Carlo Calculations in Nuclear Medicine, Bristol, Institute of Physics, 1990, pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sarrut D, et al. , “Advanced Monte Carlo simulations of emission tomography imaging systems with GATE,” Phys Med Biol, vol. 66, no. 10, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Levin C, et al. , “Removal of the effect of Compton scattering in 3-D whole body positron emission tomography by Monte Carlo,” IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging, vol. 2, pp. 1050–1054, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Barret O, et al. , “Monte Carlo simulation and scatter correction of the GE advance PET scanner with SimSET and Geant4,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 50, no. 20, p. 4823, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nadig V, Herrmann K, Mottaghy F and Schulz V, “Hybrid total-body pet scanners—current status and future perspectives,” Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, vol. 49, p. 445–459, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Visvikis D, et al. , “Use of the GATE Monte Carlo package for dosimetry applications,” Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, vol. 569, no. 2, pp. 335–340, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Alzimami K, Alkhorayef M and Spyrou N, “Comparison of Zr-89, I-124, and F-18 Imaging Characteristics in PET Using Gate Monte Carlo Simulations: Imaging,” International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, vol. 88, no. 2, p. 502, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Borys D, et al. , “ProTheRaMon—a GATE simulation framework for proton therapy range monitoring using PET imaging,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 67, no. 22, p. 224002, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Etxebeste A, et al. , “CCMod: a GATE module for Compton camera imaging simulation,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 65, no. 5, p. 055004, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Trigila C, Moghe E, Roncali E, “Technical Note: Standalone application to generate custom reflectance Look-Up Table for advanced optical Monte Carlo simulation in GATE/Geant4,” Medical Physics, vol. 48, no. 6, pp. 2800–2808, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Leung E, Revilla E, Spencer B, Xie Z, Zhang X, Omidvari N, Badawi R, Cherry S, Lu Y and Berg E, “A quantitative image reconstruction platform with integrated motion detection for total-body PET,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine, vol. 62, no. 1, p. 1549, May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dean J and Ghemawat S, “MapReduce: simplified data processing on large clusters,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 107–113, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Poole C, Cornelius I, Trapp J and Langton C, “Radiotherapy Monte Carlo simulation using cloud computing technology,” Australasian physical & engineering sciences in medicine, vol. 35, pp. 497–502, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sébastien J, et al. , “GATE: a simulation toolkit for PET and SPECT,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 49, no. 19, p. 4543, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Amazon Webservices Inc., “AWS Pricing Calculator,” [Online]. Available: https://calculator.aws/#/. [Accessed 20 11 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bert J, Perez-Ponce H, Jan S, El Bitar Z, Gueth P, Cuplov V and Chekatt H, “Hybrid GATE: A GPU/CPU implementation for imaging and therapy applications,” in 2012 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conf, Anaheim, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Garcia M-P, Bert J, Benoit D, Bardiès M and Visvikis D, “Accelerated GPU based SPECT Monte Carlo simulations,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 61, p. 4001, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].OpenGATE Collaboration, “How to use Gate on a GPU,” 08 Feb 2024. [Online]. Available: https://opengate.readthedocs.io/en/latest/how_to_use_gate_on_a_gpu.html. [Accessed 06 Mar 2024]. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lai Y, Zhong Y, Chalise A, Shao Y, Jin M, Jia X and Chi Y, “gPET: a GPU-based, accurate and efficient Monte Carlo simulation tool for PET,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 64, no. 24, p. 245002, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Galve P, Arias-Valcayo F, Villa-Abaunza A, Ibáñez P and Udías JM, “UMC-PET: a fast and flexible Monte Carlo PET simulator,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 69, no. 3, p. 035018, 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Peng Z, Lu Y, Xu Y, Li Y, Cheng B, Ni M, Chen Z, Pei X, Xie Q and Wang S, “Development of a GPU-accelerated Monte Carlo dose calculation module for nuclear medicine, ARCHER-NM: demonstration for a PET/CT imaging procedure,” Physics in Medicine & Biology, vol. 67, no. 6, p. 06NT02, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Selfridge A, Spencer B, Abdelhafez Y, Nakagawa K, Tupin J and Badawi R, “Facial Anonymization and Privacy Concerns in Total-Body PET/CT,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine, p. jnumed.122.265280, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]