Abstract

Background:

Surgical treatment of complex giant pituitary adenomas (GPAs) presents significant challenges. The efficacy and safety of combining transsphenoidal and transcranial approaches for these tumors remain controversial. In this largest cohort of patients with complex GPAs, we compared the surgical outcomes between those undergoing a combined regimen and a non-combined regimen. We also examined the differences in risks of complications, costs, and logistics between the two groups, which might offer valuable information for the appropriate management of these patients.

Patients and Methods:

This was a multicenter retrospective cohort study conducted at 13 neurosurgical centers. Consecutive patients who received a combined or non-combined regimen for complex GPAs were enrolled. The primary outcome was gross total resection, while secondary outcomes included complications, surgical duration, and relapse. A propensity score-based weighting method was used to account for differences between the groups.

Results:

Out of 647 patients [298 (46.1%) women, mean age: 48.5 ± 14.0 years] with complex GPAs, 91 were in the combined group and 556 were in the noncombined group. Compared with the noncombined regimen, the combined regimen was associated with a higher probability of gross total resection [50.5% vs. 40.6%, odds ratio (OR): 2.18, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.30–3.63, P = 0.003]. The proportion of patients with life-threatening complications was lower in the combined group than in the non-combined group (4.4% vs. 11.2%, OR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.08–0.78, P = 0.017). No marked differences were found between the groups in terms of other surgical or endocrine-related complications. However, the combined regimen exhibited a longer average surgery duration of 1.3 h (P < 0.001) and higher surgical costs of 22,000 CNY (~ 3,000 USD, P = 0.022) compared with the noncombined approach.

Conclusions:

The combined regimen offered increased rates of total resection and decreased incidence of life-threatening complications, which might be recommended as the first-line choice for these patients.

Keywords: causal inference, neuroendocrine, pituitary surgery, regimen

Introduction

Highlights

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study at 13 neurosurgical centers, encompassing patients who underwent either a combined or a non-combined regimen for the management of complex giant pituitary adenomas.

Our findings indicated that the combined regimen was correlated with a higher frequency of achieving gross total resection and a reduced occurrence of life-threatening complications when compared with the noncombined regimen.

A combined regimen may be recommended as the first-line choice for patients with complex giant pituitary adenomas.

Pituitary tumors represent 10%–12% of all intracranial neoplasms1. A significant portion of these tumors can be excised either through endonasal surgery2,3 or by the transcranial approach4,5. Pituitary adenomas with a maximal diameter of greater than or equal to 4 cm are termed giant pituitary adenomas (GPAs)6. Although rare, these complex tumors often extend into various anatomical compartments, commonly demonstrate high rates of invasiveness, and encase neurovascular structures7. Surgical intervention for these tumors poses substantial challenges, often resulting in limited resection and an elevated risk of complications, irrespective of the surgical approach – be it endonasal or transcranial8,9.

Several case series have advocated for a combined regimen using both transsphenoidal and transcranial approaches simultaneously for the effective removal of complex sellar lesions10–12. Vascular complications appear less frequent with the combined regimen than with single approaches10–12. However, the advantages and indications of this combined regimen remain a subject of debate, with some researchers arguing that the combined regimen presents a heightened risk of surgical trauma compared with the single approach. Notably, a significant portion of the current evidence is derived from studies with constrained sample sizes or those lacking direct comparisons between different regimens13,14. Consequently, a pressing question emerges: can the combined regimen optimize surgical outcomes and reduce complications compared with the non-combined regimen?

The hypothesis of this study was that a combined regimen would enhance the extent of resection in patients with complex GPAs compared with a non-combined regimen. To test this, we compared the surgical outcomes between the two regimens in a large cohort of patients with complex GPAs. We also examined the differences in the risks of complications, costs, and logistics between the two groups, which might offer valuable information for the appropriate management of these patients.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a retrospective, multicenter study across 13 neurosurgical centers in China, as detailed in Supplementary Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158. We reviewed the medical records of patients who presented to these centers between January 2014 and November 2023 to identify eligible participants, as illustrated in Supplementary Figure 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158. Notably, all participating centers were tertiary institutions situated in the capital cities of major provinces. The study received approval from the Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards of each center. The study was registered on Research Registry (researchregistry10020). The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines (Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158) and met the STROCSS criteria15. Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C159.

Eligibility criteria

Patients were consecutively enrolled if they underwent surgical intervention for complex GPAs. A tumor qualifies as a “complex GPA” if it meets the following criteria:

Maximum diameter of greater than or equal to 4 cm.

Predominantly located above the tuberculum sella.

-

Exhibits at least one of the following features:

Superior extension reaching or surpassing the roof of the third ventricle.

Lateral progression into the middle cranial fossa or temporal lobe.

Anterior progression toward the planum sphenoidale.

Posterior progression into the interpeduncular cistern.

Displays a multilobular presentation.

Encases the circle of Willis (refer to Supplementary Figure 3 for a visual representation, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158).

Exclusions included patients with expansive sphenoidal/clivus tumors only and those whose tumors were responsive to medication.

Surgical regimens

Patients underwent one of two surgical regimens: combined or noncombined.

Combined regimen: In this approach, patients underwent simultaneous treatment via both an endonasal transsphenoidal and a transcranial approach. Several neurosurgeons operated concurrently on separate areas, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The endonasal transsphenoidal team initially debulked the tumor that invaded the sphenoidal sinus, clivus, and cavernous sinus, and the superior extension of the tumor. Upon sufficient tumor decompression, the transcranial surgeon carefully dissected the tumor margins from the cranial nerves, carotid vessels, and surrounding brain tissue while preserving the perforating vessels. Surgical debulking by the transcranial team addressed the regions that were inaccessible to the endonasal team. Once all tumor margins had been delineated, both teams collaborated to evacuate the tumor, ensuring thorough and safe removal.

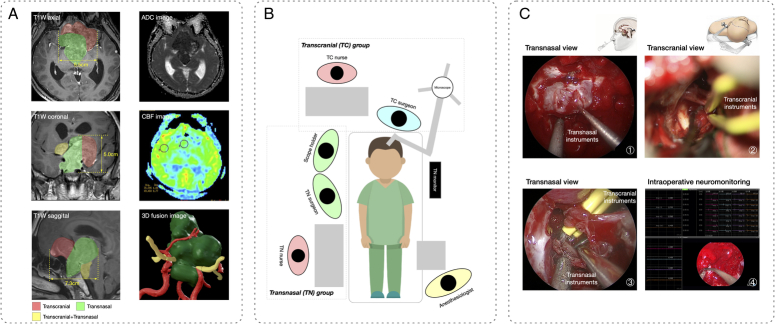

Figure 1.

A comprehensive depiction of the preoperative evaluation, surgical layout, and intraoperative screenshots of the combined regimen for a complex giant pituitary adenoma. A) The preoperative evaluation was detailed using routine contrasted T1-weighted (T1W) magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, revealing a giant adenoma with extensive anatomical compartment involvement. Preoperative neuroimaging was used to guide the selection of different surgical procedures to access various tumor extensions, as indicated by different colors on the contrasted T1W MR. The evaluation also encompassed a tumor texture analysis, using an apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) image, coupled with an assessment of blood supply, using a cerebral blood flow (CBF) image. Notably, the three-dimensional tumor-vascular-nerve fusion image (green: Tumor, red: Arteries of Willis circle, yellow: Optic nerve) was reconstructed based on the MR image to provide surgeons with a detailed spatial configuration of the tumor and its adjacent anatomical structures. B) In the combined regimen, patients underwent concurrent procedures through an endonasal transsphenoidal approach combined with a transcranial approach, which necessitated the orchestration of two operative fields and the collaborative effort of two distinct surgical teams. C) Representative intraoperative screenshots: ① Transnasal exposure and resection of the tumor were performed using transnasal suction and a dissector. ② Simultaneously, transcranial exposure and resection of the tumor were performed using transcranial suction and bipolar. ③ When the majority of the tumor had been removed, collaboration of both sets of instruments could be observed in the surgical field. ④ The intraoperative neuromonitoring technique was applied to ensure surgical safety.

Noncombined regimen: In this study, surgeons primarily used either the endonasal transsphenoidal approach or the transcranial approach. The endonasal transsphenoidal approach is typically favored for GPAs presenting with an enlarged sella turcica, clivus, or cavernous sinus invasion. The transcranial approach was reserved for tumors with excessive anterior or lateral extensions but limited intrasellar portions. If a tumor was unsuitable for complete excision during the first procedure, a secondary operation, termed the staged approach, was performed to address the residual tumor. These two procedures, either endonasal or transcranial, were scheduled 3–12 months apart.

Detailed surgical approaches to access pituitary tumors are elaborated in the Supplementary Technical Notes and Illustrative Cases, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158. In brief, the endonasal approach was implemented using either a 0° or 30° endoscope through a bilateral nostril technique. Access to the sphenoidal sinus was facilitated using a high-speed drill or osteotome, followed by the removal of the sellar floor to expose the underlying pathology. Transcranial approaches primarily encompass a pterional approach, while others include a transventricular approach and a trans-interhemispheric approach.

To ensure a safe resection procedure, a comprehensive and advanced set of techniques was employed for the combined regimen (Fig. 1). This included preoperative evaluations, such as tumor texture analysis and blood supply assessment. In addition, three-dimensional tumor vascular fusion was employed to facilitate precise surgical planning. Intraoperatively, neuromonitoring, neuronavigation, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were used.

At each participating center, a surgical team usually comprised two experienced neurosurgeons proficient in both endonasal and transcranial approaches. The combined regimen was completed through their collaborative efforts, whereas the non-combined regimen was performed by either party individually.

Confounding factors

In our observational study, certain baseline characteristics that influenced both the choice of treatment regimen and the subsequent surgical outcomes were identified as confounding factors. These include age, sex, body mass index, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus), symptoms (headache, visual disturbance, or endocrinopathy), treatment history, and tumor appearance on MRI (largest dimension, tumor volume, cavernous sinus invasion, anatomic-space extension24, multilobular appearance, and Willis circle encasement). Cavernous sinus invasion was evaluated using the Knosp classification. Anatomical space extension was recorded as sphenoidal sinus extension, clivus extension, anterior extension (to the planum sphenoidale), lateral extension (to the middle cranial fossa or temporal lobe), superior extension (to the roof of the third ventricle or above the roof of the third ventricle into the lateral ventricle), and posterior extension (into the interpeduncular cistern).

Outcomes

Outcomes were assessed within the 90 day postoperative period. The primary outcome was the extent of resection. Gross total gross resection was defined as no residual tumor on postoperative MRI, while other degrees of resection included near total (i.e. indications of possible residual tumor), subtotal (i.e. clear presence of residual tumor), and partial (i.e. only a portion of the tumor was excised)16. Secondary outcomes included surgical or endocrine complications, intraoperative blood loss, surgical duration, postoperative length of stay, and surgical costs. Major vascular injury, intracranial hemorrhage, cerebral edema, ischemic stroke, and all complications leading to death or coma (i.e. a Glasgow coma score < 13) were classified as life-threatening complications. Other surgical complications included visual deterioration, cranial nerve palsy, hypothalamus dysfunction, central nervous system infection, postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage, hydrocephalus necessitating ventricular drainage, and miscellaneous complications (pneumonia, venous thrombosis, and delirium). Endocrine complications included new occurrences of hypopituitarism and diabetes insipidus. Surgical costs were measured as the total costs incurred during the entire in-hospital stay. Patients underwent annual follow-up evaluations at outpatient clinics. For long-term outcomes, we defined recurrence (as a survival event) as evidence of adenoma that was not detected on postoperative MRI or the growth of a residual tumor. Functional impairment of the patients was assessed using the Karnofsky performance scale. Comprehensive information on the definitions of outcomes and the methodologies employed for data collection is available in the supplementary protocol, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome. A sample size of 76 in the combined group and 380 in the noncombined group was estimated to provide 90% power to detect a 20% relative risk increase in gross total resection, as significant at the 5% level. The selection of the 20% relative risk increase was grounded in pilot data obtained at center S01.

Statistical analysis

We generated a weighted cohort to balance the two surgical regimens using propensity score-based matching weighting17,18, with the propensity score estimated from logistic regression and with high-dimensional variables used to predict treatment assignment (Supplementary statistical note and code, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158). To assess the success of balancing, standardized mean differences (SMDs) were used to compare the confounding characteristics between groups after weighting. An SMD greater than 10% indicated a significant imbalance of a covariate, whereas a smaller value supported the assumption of a balance between the two treatment groups. In the weighted cohort, the statistical significance of categorical variables was described by the odds ratio (OR), and the statistical significance of continuous variables was described by the average mean difference.

The robustness of our results was examined using multiple sensitivity analyses. We (1) calculated the adjusted risk difference, (2) exploited logistic regression to estimate the treatment effect, (3) employed propensity score matching and differential matching ratios to generate treatment-effect estimations, (4) applied additional weighting methods (i.e. inverse probability weighting, overlap weighting, and standard mortality weighting) to balance characteristics between the two groups as an alternative to matching weighting, and (5) compared the combined regimen with the single approach and with the staged approach separately.

To address the heterogeneity of the treatment effects, we performed the analyses on clinically relevant subgroups (i.e. age, sex, tumor extension) by adding interaction terms. Considering the potential type-I error due to multiple comparisons, we interpreted the findings from secondary outcomes and interactions as exploratory results. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 3.4.2. A P value less than 0.05 for a two-sided comparison was considered statistically significant for the primary outcome.

Results

Confounding factors of the study participants

In our analysis, we included 647 patients diagnosed with complex GPAs, including 91 who underwent the combined regimen and 556 who received the non-combined regimen. Within the non-combined group, 361 patients were treated using the transsphenoidal approach, 131 via the transcranial approach, and 64 through staged approaches. The mean age was 48.5 (±14.0) years, and 46.1% (298) were female. The distribution of confounding factors, both pre- and post-weighting, for each group is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Unweighted and weighted cohort characteristics using combined or non-combined regimens.

| Unweighted cohort | Weighted cohort | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 647) [n (%)] | Combined (N=91) [n (%)] | Non-combined (N=556) [n (%)] | SMD | Combined (N=83.8) [n (%)] | Non-combined (N=86.6) [n (%)] | SMD | |

| Sex (Male) | 349 (53.9) | 49 (53.8) | 300 (54.0) | 0.002 | 45.2 (54.0) | 45.5 (52.5) | 0.029 |

| Age (years old) | 48.5 (14.0) | 48.3 (13.4) | 48.5 (14.0) | 0.017 | 48.4 (13.5) | 48.3 (14.1) | 0.003 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.2 (3.5) | 24.8 (3.4) | 25.2 (3.5) | 0.107 | 24.8 (3.4) | 24.5 (3.5) | 0.060 |

| Hypertension | 103 (15.9) | 13 (14.3%) | 90 (16.2) | 0.053 | 12.5 (14.9) | 13.6 (15.7) | 0.022 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 48 (7.4) | 13 (14.3) | 35 (6.3) | 0.265 | 11.4 (13.6) | 12.1 (14.0) | 0.010 |

| Symptoms | |||||||

| Visual dysfunction | 543 (83.9) | 77 (84.6) | 466 (83.8) | 0.022 | 71.1 (85.0% | 71.7 (82.8) | 0.058 |

| Headache | 189 (29.2) | 12 (12.2%) | 177 (31.8) | 0.458 | 12.0 (14.3) | 12.0 (13.9) | 0.013 |

| Related with hypopituitarisma | 274 (42.3) | 49 (53.8) | 225 (40.5) | 0.270 | 44.8 (53.4) | 46.2 (53.3) | 0.003 |

| Other# | 39 (6.0) | 8 (8.8) | 31 (5.6) | 0.125 | 7.0 (8.4) | 7.3 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| Clinical functioning phenotype$ | 99 (15.3) | 11 (12.1) | 88 (15.8) | 0.108 | 9.7 (11.5) | 9.4 (10.8) | 0.022 |

| Treatment history | |||||||

| Medication history | 26 (4.0) | 3 (3.3) | 23 (4.1) | 0.044 | 2.3 (2.7) | 2.1 (2.5) | 0.017 |

| Radiotherapy history | 17 (2.6) | 1 (1.1) | 16 (2.9) | 0.128 | 1.0 (1.2) | 1.1 (1.3) | 0.009 |

| Surgical history | 127 (19.6) | 27 (29.7) | 100 (18.0) | 0.277 | 24.5 (29.2) | 26.4 (30.4) | 0.027 |

| Tumor volume (cm3) | 32.5 (24.6) | 45.1 (38.4) | 30.5 (20.9) | 0.474 | 40.9 (30.8) | 40.9 (29.1) | <0.001 |

| Maximal diameter (cm) | 0.331 | 0.023 | |||||

| ≥ 4 < 4.5 | 268 (41.4) | 26 (28.6) | 242 (43.5) | 25.4 (30.3) | 26.9 (31.1) | ||

| ≥ 4.5 < 5 | 159 (24.6) | 24 (26.4) | 135 (24.3) | 22.3 (26.7) | 23.3 (26.9) | ||

| ≥ 5 | 220 (34.0) | 41 (45.1) | 179 (32.2) | 36.1 (43.1) | 36.3 (42.0) | ||

| Knosp grade | 0.164 | 0.026 | |||||

| I-II | 195 (31.8) | 33 (36.3) | 173 (31.2) | 30.3 (36.2) | 31.3 (36.1) | ||

| III | 187 (28.9) | 27 (29.7) | 157 (28.2) | 22.8 (27.2) | 22.9 (26.4) | ||

| IV | 257 (39.7) | 31 (34.1) | 226 (40.6) | 30.7 (36.6) | 32.5 (37.5) | ||

| Tumor extension | |||||||

| Inferior - nasal sinus or clivus | 409 (63.2) | 58 (63.7) | 351 (63.1) | 0.013 | 52.1 (62.2) | 55.6 (64.2) | 0.043 |

| Superior - till the roof of 3rd Ventricle | 436 (67.4) | 55 (60.4) | 381 (68.5) | 0.170 | 50.9 (60.8) | 52.0 (60.1) | 0.015 |

| Superior - till lateral ventricle | 36 (5.6) | 6 (6.6) | 30 (5.4) | 0.050 | 5.1 (6.1) | 4.6 (5.3) | 0.033 |

| Posterior - interpeduncular cistern | 62 (9.6) | 15 (16.5) | 47 (8.5) | 0.245 | 10.9 (13.0) | 11.1 (12.8) | 0.005 |

| Anterior - planum sphenoidale | 156 (24.1) | 40 (44.0) | 116 (20.9) | 0.509 | 33.9 (40.5) | 35.0 (40.4) | 0.002 |

| Lateral | 255 (39.4) | 52 (57.1) | 203 (36.5) | 0.423 | 46.6 (55.7) | 49.1 (56.7) | 0.021 |

| Multilobular appearance | 362 (56.0) | 77 (84.6) | 285 (51.3) | 0.765 | 69.8 (83.3) | 72.3 (83.5) | 0.006 |

| Encasement of circle of Willis | 243 (37.6) | 53 (58.2) | 190 (34.2) | 0.497 | 47.8 (57.1) | 49.9 (57.6) | 0.009 |

: Fatigue, dizziness or loss of libido; #: incidental finding; $: Hyperprolactimia, acromegaly, Cushing’s disease or hyperthyroidism; SMD: standard mean difference

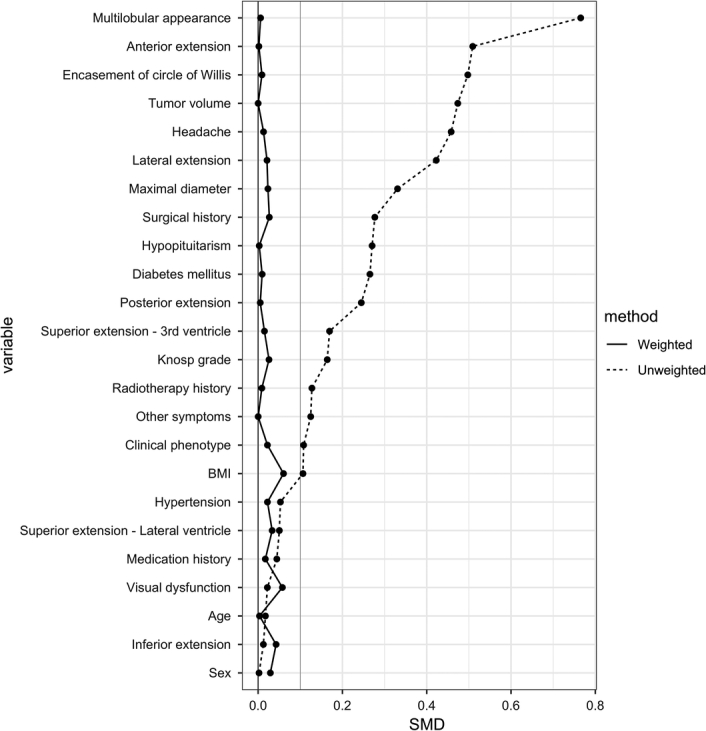

In the combined group, higher proportions of patients exhibited certain characteristics compared with the non-combined group. These characteristics included a surgical history (29.7% vs. 18.0%), tumors measuring greater than or equal to 5 cm (45.1% vs. 32.2%), anterior extension (44.0% vs. 20.9%), lateral extension (57.1% vs. 36.5%), multilobular appearance (84.6% vs. 51.3%), and Willis encasement (58.2% vs. 34.2%). Notably, each of these factors has been linked to reduced resection extent or increased complication risks. A review of the propensity score distributions indicated a significant overlap between the two treatment regimens, implying a clinically reasonable equipoise in treatment decisions (Supplementary Figure 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158). After the matching weighting process, the groups exhibited balanced characteristics, with an absolute standardized mean difference < 10% (as depicted in Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Standard mean difference (SMD) of the confounding variables in the unweighted and weighted cohorts.

Comparative outcomes of the two groups)

In the unweighted cohort, 46 (50.5%) patients in the combined group and 226 (40.6%) patients in the non-combined group achieved gross total resection. Upon adjusting for covariates in the weighted analysis, the combined regimen demonstrated an association with increased odds of gross total resection compared with the non-combined regimen [OR: 2.18, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.30–3.63, P = 0.003, as seen in Table 2]. Notably, 86.3% of tumors were resected either totally or near totally under the combined regimen, representing a significant improvement over the non-combined regimen (45.2%, refer to Supplementary Figure 5, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes in the combined and non-combined regimen.

| Events | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined (N = 91) [n (%)] | Non-combined (N = 556) [n (%)] | Unweighted | Weighted | p | |

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Gross total resection | 46 (50.5) | 226 (40.6) | 1.49 (0.96, 2.33) | 2.18 (1.30, 3.63) | 0.003 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Life-threatening complications | |||||

| All | 4 (4.4) | 62 (11.2) | 0.37 (0.11, 0.92) | 0.25 (0.08, 0.78) | 0.017 |

| Major vascular injury | 0 | 14 (2.5) | −2.5% (−3.8%, -1.2%)a | −3.7% (−7.7%, 0.3%)a | 0.068 |

| Cerebral infarction/edema | 3 (3.3) | 13 (2.3) | 1.42 (0.32, 4.53) | 0.98 (0.23, 4.11) | 0.973 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 3 (3.3) | 31 (5.6) | 0.58 (0.14, 1.66) | 0.49 (0.13, 1.94) | 0.311 |

| Coma or death | 2 (2.2) | 18 (3.2) | 0.67 (0.11, 2.38) | 0.79 (0.15, 4.16) | 0.776 |

| Other surgical complications | |||||

| Visual deterioration | 2 (2.2) | 10 (1.8) | 1.23 (0.19, 4.75) | 0.98 (0.18, 5.20) | 0.980 |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 7 (7.7) | 23 (4.1) | 1.93 (0.75, 4.43) | 1.81 (0.67, 4.88) | 0.239 |

| Hypothalamus dysfunction | 2 (2.2) | 15 (2.7) | 0.81 (0.13, 2.94) | 0.64 (0.14, 3.02) | 0.571 |

| Postoperative CSF leakage | 3 (3.3) | 25 (4.5) | 0.72 (0.17, 2.12) | 0.79 (0.21, 2.99) | 0.727 |

| CNS Infection | 6 (6.6) | 42 (7.6) | 0.86 (0.32, 1.95) | 0.55 (0.21, 1.48) | 0.239 |

| Hydrocephalus | 1 (1.1) | 16 (2.9) | 0.38 (0.02, 1.87) | 0.53 (0.06, 4.71) | 0.565 |

| Miscellaneous complications$ | 6 (6.6) | 29 (5.2) | 1.28 (0.47, 2.98) | 1.00 (0.35, 2.84) | 0.994 |

| Endocrine complications | |||||

| Newly onset hypopituitarism | 11 (12.1) | 95 (17.6) | 0.64 (0.31, 1.21) | 0.57 (0.27, 1.20) | 0.135 |

| Diabetes insipidus | 16 (17.6) | 86 (15.9) | 1.13 (0.61, 1.98) | 1.22 (0.63, 2.38) | 0.550 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 600 (400, 1075) | 400 (200, 700) | 252 (63, 443) | 41 (−147, 230) | 0.666 |

| Length of surgery (hours) | 7.0 (5.0, 8.4) | 4.5 (3.2, 6.2) | 6.0 (1.5, 2.7) | 1.3 (0.5, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Length of postsurgical stay (days) | 15 (11, 20) | 10 (7, 17) | 3.4 (1.0, 5.7) | 1.5 (−1.6, 4.6) | 0.343 |

| Cost (thousand CNY) | 113.9 (94.0, 142.5) | 70.9 (52.0, 100.1) | 36.1 (20.7, 51.7) | 22.0 (3.2, 40.7) | 0.022 |

: risk difference; $: pneumonia, venous thrombosis, and delirium; CNS: central nervous system; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; CNY: Chinese Yuan.

In the combined group, the percentage of patients experiencing life-threatening complications was notably lower than that in the non-combined group (4.4% vs. 11.2%, respectively). The OR was 0.25 (95% CI: 0.08–0.78, P = 0.017, as detailed in Table 2). When assessing individual complications in the weighted cohort, there was no clear distinction between the two groups. Similarly, no significant differences were detected in other surgical or endocrine complications. However, the combined regimen exhibited a longer surgical duration by an adjusted mean difference of 1.3 h (95% CI: 0.5–2.0 h, P < 0.001). In addition, the surgical expenses were considerably elevated for the combined regimen, with an adjusted mean difference of 22,000 CNY (~3000 USD, 95% CI: 3200–40,700 CNY, P = 0.022) compared with the non-combined approach.

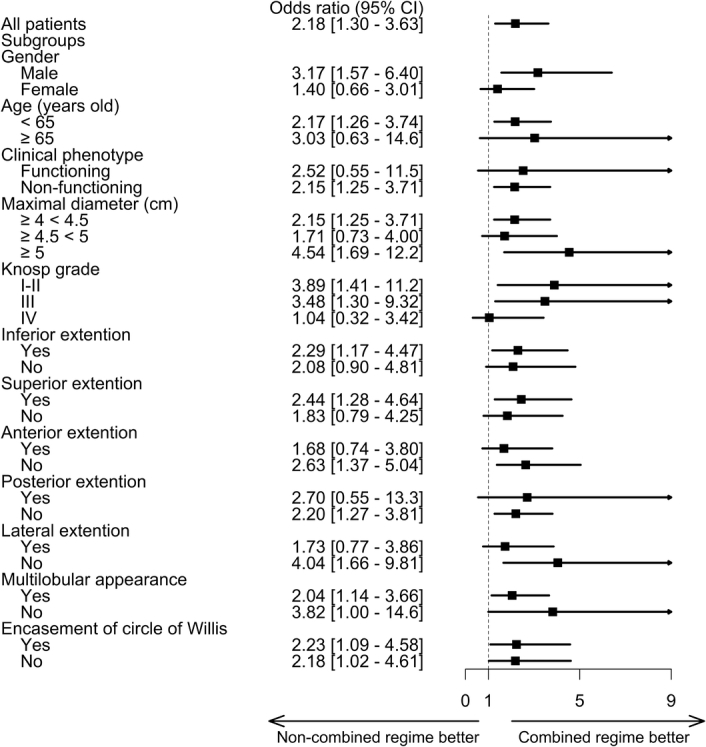

When we performed subgroup analysis within the weighted cohort, none of the interaction terms manifested any statistical significance. The increased odds of achieving gross total resection with the combined regimen remained consistent across most subgroups (as illustrated in Fig. 3). The singular exception to this observation was tumors classified with Knosp grade IV invasion.

Figure 3.

Odds ratio of the primary outcome in the weighted cohort and prespecified subgroups.

Regarding long-term prognosis, a smaller proportion of patients in the combined group required post-operative adjunctive therapy than those in the noncombined group (30.8% vs. 56.4%). The 2-year recurrence-free survival rate for the combined group was 96.0% (95% CI: 90.7%–100.0%), whereas for the non-combined group, it was 94.1% (95% CI: 91.2%–97.1%). This difference corresponds to a hazard ratio of 0.83 (95% CI: 0.18–3.93, P = 0.790, Supplementary Figure 6, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158). In the last follow-up visit, 96.7% of the patients in the combined group had a KPS score of greater than 70 compared with 92.8% of patients in the non-combined group, corresponding to an OR of 2.47 (95% CI: 0.71–8.63, P = 0.156).

Sensitivity analysis

In our sensitivity analysis employing the adjusted risk difference, consistent findings indicated an average additional 18.5% of patients attaining gross total resection through the combined regimen (Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158). Further sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome yielded corroborative results. Logistic regression yielded an OR of 2.79 (95% CI: 1.56–5.06, P = 0.001), whereas propensity score matching, across varying matching ratios, yielded concordant results: 1:1 (OR: 2.42, 95% CI: 1.33–4.50, P = 0.004), 1:3 (OR: 2.01, 95% CI: 1.24–3.26, P = 0.004), and 1:5 (OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.07–2.65, P = 0.024). Other weighting methodologies also endorsed the findings of our primary analysis, with inverse probability weighting giving an OR of 1.85 (95% CI: 1.04–3.29, P = 0.036), overlap weighting presenting an OR of 2.18 (95% CI: 1.30–3.63, P = 0.003), and standardized mortality ratio weighting indicating an OR of 2.25 (95% CI: 1.35–3.73, P = 0.002).

The noncombined regimen encompassed diverse approaches. Therefore, we conducted comparisons of the combined regimen with both the single and staged approaches separately. When compared with the single approach, the combined regimen markedly increased the probability of attaining gross total resection (OR: 2.36, 95% CI: 1.40–3.99, P = 0.001) while substantially reducing the odds of major complications (OR: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.07–0.74, P = 0.013), as delineated in Supplementary Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158. The rate of gross total resection was similar regardless of whether the surgical team opted for a transsphenoidal or transcranial approach (OR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.43–1.16, P = 0.169). Compared with the staged approach, the combined regimen was associated with an elevated likelihood of gross total resection (OR: 2.70, 95% CI: 1.11–6.58, P = 0.029). However, in terms of major complications, the combined and staged approaches were comparable. Noteworthily, the combined regimen exhibited a diminished risk of new occurrences of hypopituitarism and a shorter surgical duration compared with staged surgery.

Discussion

Since the evolution of endonasal endoscopic sinus and skull base surgeries, surgeons have attempted the transnasal procedure as a single approach to resect complex pituitary tumors. Nevertheless, this method carries considerable risks, including hemorrhaging due to residual tumor or vascular injury7,8. This study is the first and largest multicenter comparative series of complex GPAs with different surgical regimens. We demonstrated a notable enhancement in the rate of gross total resection and a significant reduction in the incidence of severe surgical complications when employing the combined regimen.

The indication for employing a combined regimen has been ambiguously described in the existing literature. In real-world practice, this regimen is often reserved for the most challenging cases, encompassing tumors with multiple surgical histories, multiple anatomical compartment extensions, multilobular configurations, and vascular encasements. Although our study was not a randomized controlled trial, preoperative clinical and radiological characteristics were meticulously examined to mitigate potential biases during the assessment of surgical regimens. Our matching weighting methodology targeted the average treatment effect within a cohort that demonstrated clinical equipoise in treatment decisions17,18.

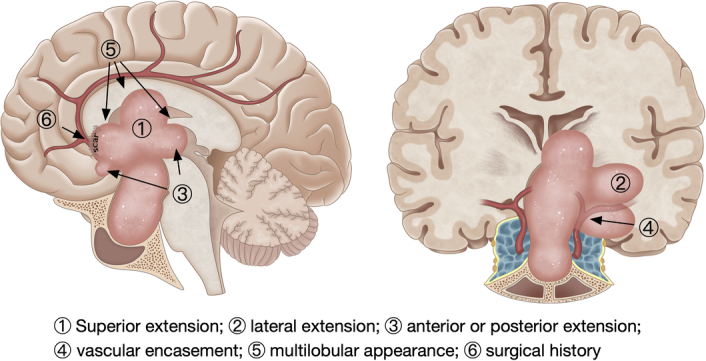

Indications for the combined regimen

In this study, we identified several key features that justify the application of a combined regimen, as depicted in Fig. 4. 1) Superior extension: Tumors with significant suprasellar extensions, particularly those invading the third or lateral ventricles and causing distortions of the hypothalamus or ventricles. 2) Lateral extension: Tumors that spread beyond the plane of the cranial nerves in the cavernous sinus and are inaccessible via a routine transnasal approach, thus necessitating an additional open procedure for comprehensive tumor removal. 3) Anterior or posterior extension: Although extended transsphenoidal approaches may address midline tumors, a combined regimen may prevent injuries to the anterior cerebral artery. 4) Vascular encasement: Tumors adhering to vessels, such as the circle of Willis (notably the anterior communicating artery and the internal carotid artery bifurcation), present substantial risks. Potential hemorrhages from these regions can be particularly challenging to address during a purely transnasal operation. 5) Multilobular appearance: A multilobulated structure typically indicates adhesions to vascular structures or the optic nerve. 6) Surgical history: Recurrent pituitary adenomas often result in significant scar tissue and surgical complexities during reoperations. Collectively, these features push these conditions to the edge of viability for any single existing surgical approach, as established in previous studies7,8.

Figure 4.

Key tumor configurations favoring the combined regimen include the following: 1) superior extension, 2) lateral extension, 3) anterior or posterior extension, 4) vascular encasement, 5) multilobular appearance, and 6) surgical history.

Pros and cons of the combined regime

The combined regimen offers several benefits: 1) Panoramic visualization, by offering comprehensive 360-degree perspective, effectively obviating any potential blind spots; 2) vascular integrity, by facilitating meticulous dissection of major blood vessels while ensuring the preservation of perforating vessels; and 3) optimized resection, in that the collaboration of “above and below” enhances the extent of resection. Compared with conventional, non-combined regimens, we increased the rate of gross total resections while concurrently decreasing the incidence of severe complications. In our cohort, total or near-total resections were realized in most cases. Even among those with subtotal resection, the remaining tumors were predominantly confined to the cavernous sinus, thereby substantially mitigating the risk of postoperative hemorrhages. This finding is in alignment with the outcomes of other studies that employed the combined regimen (Supplementary Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158)10–13,19–22. Moreover, we recorded no major vascular injuries in the combined group, which is in contrast to the 2.5% incidence rate observed in the non-combined group – a finding that aligns with the 1.2%–2.5% range in the literature review (Supplementary Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158)23–27.

The combined regimen encompasses two distinct surgical approaches, necessitating the use of additional equipment and instruments and the incorporation of intraoperative monitoring and/or MRI scans. These factors cumulatively contribute to the elongation of the surgical duration. Financially, the higher cost associated with the combined regimen can be attributed to the pricing policy categorizing the combined surgery as an innovative technique. This classification arises because the procedure demands intricate surgical maneuvers, heightened coordination, more extensive personnel involvement, and investment in advanced hardware. Currently, the combined regimen has not gained widespread acceptance, mainly due to the prevailing skepticism regarding its safety and effectiveness. A learning curve exists before a surgical team can become proficient in this combined regimen. Our data suggest that a team of experienced neurosurgeons requires approximately 10–15 operations (included in our cohort) to familiarize themselves with this approach – a finding that is further detailed in Supplementary Figure 7, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/C158.

In summary, the combined regimen demonstrated absolute advantages in enhancing resection rates and reducing the incidence of life-threatening complications, while the other risks were comparable, although the patients in the combined group were exposed to potential risks from both transsphenoidal and transcranial approaches. Therefore, the combined regimen may be recommended as the first-line choice for these patients in centers with qualified surgeons and sufficient equipment. Considering the requirement of additional equipment and personnel involvement, as well as the elongation of surgical duration, the combined regimen could be performed according to the following strategy: a single approach may be initially employed, while a simultaneous combined approach may be implemented depending on intraoperative observations such as tumor consistency, blood supply, adjacent adhesion, and the surgeon’s expertise.

Limitations

First, while we have accounted for all known confounders, our findings warrant careful interpretation given the potential for residual unmeasured confounders. This study lays the groundwork for a future randomized controlled trial, although the feasibility of such a trial may be compromised by the variability in surgeons’ preferences and experience, as well as patients’ preferences across different institutions. Nevertheless, the extensive sample size of our multicenter series on this uncommon disease contributes valuable insights into the management of complex GPAs28.

Second, our analysis of disease recurrence was constrained by the limited follow-up duration, and our survival analysis indicated that the combined approach did not confer a discernible advantage. Because pituitary adenoma is a benign tumor, a longer period is required to adequately assess recurrence events. It is important to note that patients with residual tumors often receive adjunctive therapies, such as medication or radiotherapy, which further diminish the likelihood of recurrence. Although a direct survival benefit was not evident in our study, it is noteworthy that fewer patients in the combined group required postoperative adjunctive therapy than those in the non-combined group.

Finally, the intervention demonstrated clinical heterogeneity within each group, and this study was not specifically designed to evaluate the combined regimen versus any single approach. It is important to note that even in a well-conducted randomized controlled trial, the intervention for patients with complex GPAs would be inherently heterogeneous, depending on the individual pre-operative imaging findings. Our sensitive analysis revealed that the primary outcome remained consistent irrespective of the surgical approach adopted by the team in the noncombined group (i.e., transsphenoidal, transcranial, or staged approach). It is noteworthy that while the frequency of major complications appeared to be comparable between the combined and staged regimens, the patients who experienced life-threatening complications during the initial surgery may not have been presented with an opportunity for a subsequent staged procedure.

Conclusions

The combined regimen offered increased rates of total resection and decreased incidence of life-threatening complications, which might be recommended as the first-line choice for these patients.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards at each center reviewed and approved the study protocol (KY2022-060).

Sources of funding

This work was sponsored by National Natural Science Funds of China (U21A20389), Joint Funds for Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (No. 2021Y9089) and University-Industry Research Joint Innovation Project of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (No. 2023Y4018).

Author contribution

N.Q., W.G., X.D., T.X., G.Z., and N.W. are considered co–first authors. Concept and design: X.D., T.X., G.Z., N.W., L.C., Y.Q., H.M., A.W., C.M., M.L., C.J., Y.W., Y.Z.; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: N.Q., W.G., P.W., Y.B., Z.C., Z.Z., J.L., S.S., M.L., W.T., X.Y., W.W., W.C.; drafting of the manuscript: N.Q.; critical revision of the manuscript: X.Z., X.C., M.S., X.S., C.J., Y.W., Y.Z.; statistical analysis: N.Q. (who had two-year statistical experience at Harvard T.H.C. School of Public Health), Z.W.; administrative, technical, or material support: S.Y., Z.Y., Z.M.; supervision: C.J. Y.W., Y.Z.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

None.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: Clinicaltrial.gov

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: NCT05448690

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05448690?term=combined&cond=pituitary&draw=2&rank=4.

Guarantor

Nidan Qiao and Yao Zhao.

Data availability statement

De-identified data would be available upon request after IRB approval.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Nidan Qiao, Wei Gao, Xingli Deng, Tao Xin, Gangli Zhang and Nan Wu, contributed equally to this work

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww.com/international-journal-of-surgery.

Published online 18 March 2024

Contributor Information

Nidan Qiao, Email: qiaonidan@fudan.edu.cn.

Wei Gao, Email: gwpower@126.com.

Xingli Deng, Email: dxlkmmu@163.com.

Tao Xin, Email: drxintao@126.com.

Gangli Zhang, Email: Zhanggangli1973@163.com.

Nan Wu, Email: wunan881@tmmu.edu.cn.

Pan Wang, Email: wangpan@tmmu.edu.cn.

Yunke Bi, Email: doctorbyk@163.com.

Zixiang Cong, Email: congzixiang86@126.com.

Zhiyi Zhou, Email: zzyhenry@sina.com.

Junjun Li, Email: lijunjun@kmmu.edu.cn.

Shengyu Sun, Email: sunshengyu302179@163.com.

Meng Li, Email: drlimeng@126.com.

Wenlong Tang, Email: tangwenlong06150616@126.com.

Xiaorong Yan, Email: 178603351@qq.com.

Wenxiong Wang, Email: 243383935@qq.com.

Wenjin Qiu, Email: wenjinqiu@gmc.edu.cn.

Shun Yao, Email: yaoshunns@126.com.

Zhao Ye, Email: yezhaozj663812@126.com.

Zengyi Ma, Email: Zengyima@foxmail.com.

Xiang Zhou, Email: xiangzhou98@outlook.com.

Xiaoyun Cao, Email: caoxiaoyun2594@163.com.

Ming Shen, Email: samshenming@yahoo.com.

Xuefei Shou, Email: shouxf@vip.sina.com.

Zhaoyun Zhang, Email: zhaoyunzhang@fudan.edu.cn.

Zhenyu Wu, Email: zyw@fudan.edu.cn.

Liangzhao Chu, Email: chulz_gymns@163.com.

Yongming Qiu, Email: qiuzhoub@126.com.

Hui Ma, Email: mahui0528@aliyun.com.

Anhua Wu, Email: wuanhua@yahoo.com.

Chiyuan Ma, Email: machiyuan_nju@126.com.

Meiqing Lou, Email: meiqing_lou@foxmail.com.

Changzhen Jiang, Email: 893416880@qq.com.

Yongfei Wang, Email: eamns@hotmail.com.

Yao Zhao, Email: zhaoyao@huashan.org.cn.

References

- 1. Molitch ME. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pituitary Adenomas: A Review. JAMA 2017;317:516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cappabianca P, de Divitiis E. Endoscopy and transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery 2004;54:1043–1048; discussions 1048–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paluzzi A, Fernandez-Miranda JC, Tonya Stefko S, et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach for pituitary adenomas: a series of 555 patients. Pituitary 2014;17:307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Youssef AS, Agazzi S, van Loveren HR. Transcranial surgery for pituitary adenomas. Neurosurgery 2005;57(1 Suppl):168–175; discussion 168–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Solari D, Zenga F, Angileri FF, et al. A Survey on Pituitary Surgery in Italy. World Neurosurg 2019;123:e440–e449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iglesias P, Rodríguez Berrocal V, Díez JJ. Giant pituitary adenoma: histological types, clinical features and therapeutic approaches. Endocrine 2018;61:407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zada G, Du R, Laws ER, Jr. Defining the “edge of the envelope”: patient selection in treating complex sellar-based neoplasms via transsphenoidal versus open craniotomy. J Neurosurg 2011;114:286–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Laws ER, Jr. Vascular complications of transsphenoidal surgery. Pituitary 1999;2:163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cavallo LM, Briganti F, Cappabianca P, et al. Hemorrhagic vascular complications of endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2004;47:145–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alleyne CH, Jr, Barrow DL, Oyesiku NM. Combined transsphenoidal and pterional craniotomy approach to giant pituitary tumors. Surg Neurol 2002;57:380–390; discussion 390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nishioka H, Hara T, Usui M, et al. Simultaneous combined supra-infrasellar approach for giant/large multilobulated pituitary adenomas. World Neurosurg 2012;77:533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuga D, Toda M, Ozawa H, et al. Endoscopic Endonasal Approach Combined with a Simultaneous Transcranial Approach for Giant Pituitary Tumors. World Neurosurg 2019;121:173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Han S, Gao W, Jing Z, et al. How to deal with giant pituitary adenomas: transsphenoidal or transcranial, simultaneous or two-staged? J Neurooncol 2017;132:313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishioka H, Hara T, Nagata Y, et al. Inherent Tumor Characteristics That Limit Effective and Safe Resection of Giant Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas. World Neurosurg 2017;106:645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mathew G, Agha R, for the STROCSS Group. STROCSS 2021 . Strengthening the Reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in Surgery. International Journal of Surgery 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makarenko S, Alzahrani I, Karsy M, et al. Outcomes and surgical nuances in management of giant pituitary adenomas: a review of 108 cases in the endoscopic era. J Neurosurg 2022;137:635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Desai RJ, Franklin JM. Alternative approaches for confounding adjustment in observational studies using weighting based on the propensity score: a primer for practitioners. BMJ 2019;367:l5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoshida K, Hernández-Díaz S, Solomon DH, et al. Matching Weights to Simultaneously Compare Three Treatment Groups: Comparison to Three-way Matching. Epidemiology 2017;28:387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nagata Y, Watanabe T, Nagatani T, et al. Fully endoscopic combined transsphenoidal and supraorbital keyhole approach for parasellar lesions. J Neurosurg 2018;128:685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leung GK, Law HY, Hung KN, et al. Combined simultaneous transcranial and transsphenoidal resection of large-to-giant pituitary adenomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011;153:1401–1408; discussion 1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Inoue A, Suehiro S, Ohnishi T, et al. Simultaneous combined endoscopic endonasal and transcranial surgery for giant pituitary adenomas: Tips and traps in operative indication and procedure. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2022;218:107281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D’Ambrosio AL, Syed ON, Grobelny BT, et al. Simultaneous above and below approach to giant pituitary adenomas: surgical regimens and long-term follow-up. Pituitary 2009;12:217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinha S, Sharma BS. Giant pituitary adenomas--an enigma revisited. Microsurgical treatment regimens and outcome in a series of 250 patients. Br J Neurosurg 2010;24:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yano S, Hide T, Shinojima N. Efficacy and Complications of Endoscopic Skull Base Surgery for Giant Pituitary Adenomas. World Neurosurg 2017;99:533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rahimli T, Hidayetov T, Yusifli Z, et al. Endoscopic Endonasal Approach to Giant Pituitary Adenomas: Surgical Outcomes and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg 2021;149:e1043–e1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shukla D, Konar S, Kulkarni A, et al. A new comprehensive grading for giant pituitary adenomas: SLAP grading. Br J Neurosurg 2022;36:377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Micko A, Agam MS, Brunswick A, et al. Treatment regimens for giant pituitary adenomas in the era of endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery: a multicenter series. J Neurosurg 2021;136:776–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuo JS, Barkhoudarian G, Farrell CJ, et al. Congress of Neurological Surgeons Systematic Review and Evidence-Based Guideline on Surgical Techniques and Technologies for the Management of Patients With Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas. Neurosurgery 2016;79:E536–E538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data would be available upon request after IRB approval.