Abstract

Halogens (chlorine, bromine, and iodine) are known to profoundly influence atmospheric oxidants (hydroxyl radical (OH), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2), ozone (O3), and nitrate radical (NO3)) in the troposphere and subsequently affecting air quality. However, their impact on atmospheric oxidation and air pollution in coastal areas in China is poorly characterized. In this study, we use the WRF-CMAQ (Weather Research and Forecasting-Community Multiscale Air Quality) model with full halogen chemistry and process analysis to assess the influences and pathways of halogens on atmospheric oxidants in the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region, a typical coastal city cluster in China. Halogens cause the annual OH radical increase by up to 16.4% and NO3 decrease by up to 45.3%. O3 increases by 2.0% in the YRD but decreases by 3.3% in marine environment. Halogen induced changes in atmospheric oxidants lead to a general increase of atmospheric oxidation capacity by 5.1% (maximum 48.4%). The production rate of OH (POH) in the YRD is enhanced by anthropogenic chlorine through both increased HO2 pathway and hypohalous acid photolysis pathway, while POH over ocean is enhanced by oceanic halogens through converting HO2 into hypohalous acid. Anthropogenic chlorine enhances both O3 and NO3 production (PNO3) rates through influencing their precursors while oceanic halogens reduce PNO3 and directly destroy ozone. Iodine contributed most (on average of 91% in oceanic halogens) in reducing production rates of oxidants. Thus, halogen emissions and potential effects of halogens on air quality need to be considered in air quality policies and regulations in the YRD region.

Keywords: CMAQ, halogen chemistry, atmospheric oxidants, atmospheric oxidation capacity, process analysis

1. Introduction

Recently, China has achieved a significant decline in primary pollutants (Zheng et al., 2018). However, the level of surface ozone (O3), a typical secondary pollutant, has gradually increased and become one of major contributors to air pollution in China, and the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region suffered a combined pollution of O3 and fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Secondary air pollutants are formed through photochemical or oxidation processes (i.e., volatile organic compounds (VOCs) oxidized by radicals to form O3) in the atmosphere, presenting a nonlinear correlation with their precursors. Therefore, knowledge in mechanisms between atmospheric oxidants and pollutants is required (Lu et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2019).

Halogens are known as a major contributor to stratospheric O3 depletion events (Lary, 1997). Reactive halogen species (RHS) may also play an important role in the chemistry in the troposphere. Recent studies have given a comprehensive overview on halogen chemistry in the troposphere (Saiz-Lopez and von Glasow, 2012; Simpson et al., 2015). RHS can destroy O3 through catalytic cycle, change the partitioning of hydrogen oxides (HOX) and nitrogen oxides (NOX), and oxidize VOCs to produce peroxy radicals leading to O3 formation in polluted area (Atkinson et al., 2006). In coastal areas where sea spray aerosols (SSA) are emitted to the atmosphere, heterogeneous reactions between halides and gas-phase compounds occur, activating RHS into the atmosphere (Osthoff et al., 2008).

Several studies using large-scale models have been conducted to examine the effect of halogen chemistry in the troposphere. Sarwar et al. (2012), Parrella et al. (2012) and Saiz-Lopez et al. (2014) implemented initial chlorine, bromine and iodine chemistry in hemispheric CMAQ (Community Multiscale Air Quality), GEOS-Chem and CAM-Chem (Community Atmospheric Model with Chemistry) model. For chlorine, the chemistry reduced the Normalized Mean Bias (NMB) of predicted ozone for 1.4% and predicted levels of nitryl chloride (ClNO2) are similar to the observed values reported across the United States. For bromine, the modeled BrO reproduced major features of the satellite observations including the increase with latitude and the seasonal maxima in different latitudes. For iodine, the simulated vertical profile of IO was in agreement with field measurements over the tropical oceans. This result proposed the existence of a “tropical ring of atomic iodine” and subsequent ozone loss ranged from 11% to 27%. Sarwar et al. (2019) implemented bromine and iodine chemistry and oceanic emissions in CMAQ to study their role in background O3 in the northern hemisphere. The bromine/iodine chemistry enhances BrO and IO levels by a factor of ~2.0 and ~1.5 on average, respectively. Predicted IO levels were similar to these reported observed values ranging from 0.4 to 1.0 pptV while BrO levels were underpredicted. Halogen chemistry could reduce ozone biases by 2~6 ppbv at most coastal and oceanic sites with less deterioration in other regions. More regional studies have been conducted with updated halogen chemistry in testbeds among the U. S., tropical east Pacific, Europe and northern Indian Ocean (Badia et al., 2019; Li et al., 2019; Mahajan et al., 2021; Womack et al., 2023). These modeling studies exhibited well in capturing either vertical or horizontal profile of IO and BrO levels against the observations, and suggested a non-negligible influence on ozone as well as other related pollutants.

The modeling studies in China mainly focused on the effect of chlorine chemistry on ClNO2 uptake from aerosols and surface O3 in WRF-Chem (Weather Research and Forecasting model coupled with Chemistry) and CMAQ (Li et al., 2016; Qiu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2017). Simulations indicated an enhancement on O3 by 5~20% while ClNO2 predictions reproduced the same order of magnitude as observed values with marginal differences due to uncertainties in meteorological or chemical schemes. Huang et al. (2021) implemented CMAQ with embedded bromine and iodine chemistry to examine the ocean halogen-mediated O3 loss and vertical profile over Asia-Pacific. Results showed that NMB for O3 in January was reduced by 6.3% and a higher index of agreement in O3 with 0.61 for ocean halogen chemistry. O3 loss exhibited a strong seasonal cycle and could reach −41~−44% in maximum over the ocean. Li et al. (2020) and Li et al. (2021c) adopted WRF-Chem with state-of-the-art halogen chemistry and sources to study the influence in atmospheric oxidants and haze pollution by halogens in northern China. Simulations with halogen chemistry reproduces the routine gas-phase pollutants successfully although ClNO2 was underestimated with a NMB of - 25.3% and bromine species were simulated with an average of 71 pptV compared to the observation of 105 pptV. The inclusion of halogen chemistry and sources resulted from the enhancements of atmospheric oxidation and loadings of fine aerosols in northern China by 10~20% and 21% on average, respectively. A few more studies have focused on chemical reactions between oceanic halogens and ship-originated air pollutants and hydroxyl radicals (OH) over the East Asia seas (Fan and Li, 2022; Li et al., 2021b).

Modeling resolutions in previous studies were majorly 27km or 12km (Fan and Li, 2022; Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020; Mahajan et al., 2021; Womack et al., 2023). The coarse resolutions may limit further detailed analysis in a specific region. On the other hand, human activities could also affect the emission of halogen precursors, which were scarcely considered, putting uncertainties in the modeling studies. Therefore, we presented a comprehensive study using the WRF-CMAQ model with 3 km resolution focusing on the YRD region, a populated coastal area. Elaborated halogen chemistry, and an up-to-date anthropogenic chlorine emission inventory were adopted in this study. We quantitatively assessed the impact of RHS on air oxidants and atmospheric oxidation capacity from different perspectives in 2018. The process analysis (PA) was employed to perform a detailed breakdown of individual impacts and contributions on air quality within reactions from halogens. The results of this study may serve as an overview with respect to the role of comprehensive halogen chemistry in the aggravation of atmospheric oxidants and oxidation capacity in the YRD city-cluster.

2. Material and method

2.1. Model configuration

In this study, Weather Research and Forecasting-Community Multiscale Air Quality Model system (WRF-CMAQ) was used to assess the impact of halogen chemistry on regional air quality. The WRF model v4.2.1 was used to simulate meteorological fields and the CMAQ model v5.3.3 with process analysis was used to simulate chemical fields. Specific parameterization schemes were included in Table S1. We adopted detailed halogen chemistry and emission parameterizations by Sarwar et al. (2019), including 38 gas-phase and 4 heterogeneous chemical reactions for bromine, and 44 gas-phase and 9 heterogeneous chemical reactions for iodine with carbon bond 6 mechanism (Luecken et al., 2019) in CMAQ to investigate the overall impact of halogens.

2.2. Data

For meteorological field simulated by WRF, 1° × 1° NCEP FNL Operational Model Global Tropospheric Analyses dataset was used (ds038.2, ds351.0 and ds461.0). Observation datasets ds351.0 and ds461.0 were prepared for meteorological data assimilation (Liu et al., 2008). The Multi-resolution Emission Inventory in China (MEIC) (www.meicmodel.org.cn) (Li et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2018) with 0.25°×0.25° spatial resolution, and 0.1°×0.1° shipping emission inventory model (SEIM) (Liu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019) were used for routine anthropogenic emissions. The temporal allocation and the spatial interpolation for MEIC and SEIM have been conducted in accordance to CMAQ modeling domain. Base year of both MEIC and SEIM is 2017 without routine biogenic emissions.

For halogen emissions, sources of marine halogen species were considered (Fig.S1): an oceanic source of halocarbons from biological activity (CHBr3, CH2Br2, CH2BrCl, CHBrCl2, CHBr2Cl, CH3I, CH2ICl, CH2IBr, CH2I2), and inorganic iodine from ocean (HOI and I2). Marine halogen emissions were calculated online following the parameterization method by Sarwar et al. (2019). Halocarbon emissions were estimated using monthly average climatological chl-α concentrations obtained from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS, oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/cgi/l3). Inorganic iodine was estimated using sea surface temperature, wind speed, surface ozone concentration and sea surface iodide ions from the model (MacDonald et al., 2014).

In our study, an up-to-date (2017) and high-resolution (4 km) anthropogenic inventory (Fig.S2) of major chlorine precursors (HCl, fine particulate Cl−, Cl2 and HOCl) for the YRD region was used (Yi et al., 2021). The emission inventory was developed based on a bottom-up method with detailed emission factors (sources of emissions, emission control policies, etc.) and county-level activity data. Although the influence of anthropogenic chlorine emissions other than natural sources remained uncertain and negligible from a global perspective (Wang et al., 2019), numbers of observations in China have confirmed the potential existence of chlorine species derived from anthropogenic sources (Tham et al., 2016; Wang and Ruiz, 2017; Yang et al., 2018). With the increasing industrial emissions and anthropogenic activities, it is necessary to include anthropogenic chlorine emissions in evaluating the overall impact of halogen species on air quality in the YRD region.

2.3. Simulation setup

A three-layer nested grid was used in this study as shown in Fig.S3. Horizontal resolutions for each domain were 27 km, 9 km and 3 km, respectively, covering Shanghai and most of the YRD region with 15 vertical layers of varying thickness from the surface to 50-hPa altitude. Halogen chemistry would make an impact in the coastline of the YRD, causing influences on both regional transport and atmosphere chemistry. Initial and boundary data for the outer domain were simulated under clean air condition. Initial and boundary data for inner domains were extracted from simulated concentrations of the outer domains using MEIC and SEIM without halogen emissions and chemistry. The simulation with PA was conducted for the entire year of 2018, with a spin-up period of 15 days. Besides, we divided 12 months into 4 seasons: March, April, and May for spring; June, July, and August for summer; September, October, and November for autumn; and January, February, and December for winter.

In this study, we conducted six sets of simulations shown in Table 1. Differences between BASE and HAL cases represented the comprehensive impact of halogen chemistry on air quality. Four more sensitive cases were conducted by zeroing out different emission input of halogens. By comparing BASE and EMIS_OCN cases we could investigate impact of oceanic halogen emissions. EMIS_I, EMIS_BR and EMIS_CL were 3 sensitive cases that used halogen emissions respectively to investigate individual impacts by different halogens.

Table 1.

Simulation Cases Setup

| Cases | Anthropogenic chlorine emission |

Bromine emission |

Iodine emission |

Halogen chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASE | × | × | × | × |

| HAL | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| EMIS_OCN | × | √ | √ | √ |

| EMIS_I | × | Zeroed out | √ | √ |

| EMIS_BR | × | √ | Zeroed out | √ |

| EMIS_CL | √ | × | × | √ |

Note: × refers to emissions that were excluded from emission inventories, Zeroed out refers to inline emissions that were scaled to 0 in emission factors using Detailed Emissions Scaling, Isolation and Diagnostics Module (DESID) in CMAQ.

2.4. Atmospheric oxidation capacity calculation

The physical and chemical states of the atmosphere are influenced in the presence of trace gases such as VOCs. The oxidizing capacity of the atmosphere determines the amount of these trace gases and their removal rate (Elshorbany et al., 2009). In this study, we adopted a mathematical method to quantify the effects of halogens on atmospheric oxidation capacity (AOC). AOC is defined as the multiply of major oxidants, their reactants, and corresponding reaction rates (Equation 1) (Li et al., 2020). AOC is a uniformed numerical value to quantify contributions of different oxidants towards atmospheric oxidation capacity (Xue et al., 2015).

| (1) |

In Equation 1, [] is the concentration of oxidant (molecules cm−3), and represents the number of oxidants and reactant species, , is the number of carbon atoms in reactant [] is the concentration of reactant (molecules cm−3), and is the second-order reaction rate constant of oxidant and reactant (cm3 molecules−1 s−1). We included all VOC species defined in CMAQ, carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4) as reactants to calculate AOC. Oxidants that react with reactants above were OH, O3, NO3 (nitrate radical), and Cl (chlorine radical). The reactions between oxidants and reactants are shown in the Table S2.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Model evaluation

In order to evaluate the model results, both WRF and CMAQ simulations were evaluated using ground-level observation data obtained from national air quality forecast platform of MEE (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/). The calculation of the indicators was listed in Table S3. For WRF model, 6 representative monitoring stations from different cities in the YRD region were selected. Simulated meteorological parameters in 2018 by WRF presented consistent temporal trends and close value ranges with observations in daily average time series comparison (Fig.S4 and Table S4). WRF model is capable of reproducing surface temperature and humidity (with −4.3% and −12.7% in Normalized Mean Bias, NMB, respectively) although wind speed was slightly underestimated with a NMB of −22.9%. In general, WRF model produced acceptable meteorological results in the research domain and could be used as input for the CMAQ model.

Model performances of CMAQ in BASE and HAL cases were evaluated by comparing simulated pollutant species with observations from 40 national air quality monitoring sites in the YRD region. Time-series comparison was conducted between simulations and observations of pollutants (Fig.S5), and verifications of simulated daily average concentration were listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluations of simulated pollutants by CMAQ in BASE and HAL cases

| Pollutants (μg/m3) |

R | NMB (%) | RMSE (μg/m3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASE | HAL | BASE | HAL | BASE | HAL | |

| MDA8-O3 | 0.7320 | 0.7227 | 13.78 | 14.73 | 33.29 | 34.03 |

| NO2 | 0.7768 | 0.7801 | 7.05 | 6.78 | 10.72 | 10.63 |

| PM2.5 | 0.8629 | 0.8643 | 46.04 | 45.86 | 27.60 | 28.10 |

| SO2 | 0.7405 | 0.7403 | 11.43 | 11.21 | 2.77 | 2.78 |

In BASE case, CMAQ model presented relatively good correlation and less bias on simulating MDA8-O3, NO2 (nitrogen dioxide) and SO2 (sulfur dioxide), with NMB range from 7% to 14% and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) between 3-33%. The implementation of halogen chemistry and oceanic emissions in EMIS_OCN case could represent the influence of halogens on model performances (Table S5). The results indicated that halogen chemistry could slightly improve model performance especially for O3. NMB of O3 was reduced by 1.44% while NMB of other pollutants were reduced by 0.3~0.6%. The inclusion of anthropogenic chlorine emissions in HAL case indicated the enhancement effect on the burden of ozone pollution by chlorine, which would be further discussed. Still, the NMB for other routine pollutants were lower than NMB in BASE case, representing an acceptable result. Simulated PM2.5 was overestimated with NMB of 46% but in good correlation with R of 0.86.

The CMAQ simulations were subjected to some uncertainties in emission inventories. For MEIC, calculated uncertainties were the lowest for NOX (−28%~33%) and highest for NH3 (−58%~117%). The overall uncertainties were reduced in comparison of previous YRD emission inventories (An et al., 2021). For SEIM, the Monte Carlo method reported a total uncertainty for CO2 at about 3%, and other pollutants were about 4~6% (Liu et al., 2016). For anthropogenic chlorine emissions, the uncertainties were estimated using Monte Carlo methods with uncertainties range of −26.8~16.8% (HCl), −57.4%~56.8% (Cl−), −105.7%~166.5% (Cl2), and −75.1%~94.5% (HOCl) (Yi et al., 2021). Furthermore, aerosol species mapping in different chemical mechanisms might account for overestimate in PM2.5 (Chen et al., 2022) and biases from meteorological fields (i.e. wind speed underestimation) might affect the diffusion and advection of pollutants. Overall bias and R of all simulated pollutants between observations were within the acceptable range, suggesting that CMAQ model results could be used to investigate the effect of halogen chemistry on air quality over the YRD region.

3.2. Simulated reactive halogen species

Spatial distributions of simulated RHS were shown in Fig.1. In HAL case, CMAQ model simulated a prominent loading (over 1000 pptV) of inorganic chlorine species (Cly = Cl + Cl2 + ClO + HCl + HOCl + ClNO3 + ClNO2 + BrCl + ICl) in the YRD region, especially over the region with higher anthropogenic chloride emissions. Cly loading peaked in winter and was lowest in summer on lands, while the loading of Cly exhibited an opposite trend along the coastal area. The difference between temporal variation of Cly on the land and the ocean might be due to the low temperature induced accumulations of N2O5 in winter and higher biogenic activities and activations of chloride from SSA in summer (Fig.S6).

Fig.1.

Simulated seasonal average of daily-maximum of Cly (left column), Bry (middle), and Iy (right) (pptV) in HAL case

In our study, inorganic bromine (Bry = Br + Br2 + BrO + HBr + HOBr + BrNO3 + BrNO2 + BrCl + IBr) and iodine (Iy = I + I2 + IO + I2O2 + I2O3 + I2O4 + HI + HOI + INO3 + INO2 + INO + ICl + IBr) were also estimated with a non-negligible amount (over 0.4 pptV) on lands and a higher level along the coast. Bry and Iy exhibited a consistent seasonal variation which were generally influenced by the solar radiation and sea surface temperature. Connections between emissions and simulations of RHS were examined by evaluating IPR (integrated process rate) results. The spatial distribution and seasonal variation of Bry and Iy were roughly in line with the emissions of oceanic bromine and iodine species (Fig.S8) which was higher in summer (over 5 pptV and 15 pptV in coastal areas) and lower in winter. Meanwhile, wind direction in China is governed by the Asian monsoon (Li et al., 2020). In summer, the southeaster monsoon blows oceanic emissions of RHS into the land, enhancing RHS level on lands and along the coast. In contrast, the norther monsoon in winter blows the air from the land to the ocean and thus prevents the ocean emitted RHS from entering Mainland China (Fig.S9).

Simulated halogen species were evaluated using available observations and measurements till now. For ClNO2, a reservoir of NOx (oxides of nitrogen) and reactive chlorine radicals, simulations in the current study showed that it peaked in winter and reached the lowest in summer (Fig.S6). For the higher ClNO2 in coastal area than the inlands in Fig.S6a, the result is probably due to the chlorine in SSA in the HAL case. Differences of simulated N2O5 concentration between HAL and BASE cases and particulate chlorine (PCl) were shown in Fig.3-1. The increase of ClNO2 exhibits a similar pattern to the decrease of N2O5 in the HAL case compared to BASE case (Fig.S7a, b), indicating the enhancement effect of chlorine in SSA on ClNO2. The ambient atmosphere is blown from urban YRD to coastal area due to west-northern monsoon in cooler seasons and creating a favorable condition for N2O5 to accumulate over the coastline because of shorter sunlight duration and atmosphere circulation. Besides, simulated PCl concentration in spring is the second highest among 2018 and in winter it is the lowest. Although NOx emissions from vessels may compensate for the loss of N2O5 along ship tracks, these conditions may lead to a higher ClNO2 in coastal area in spring. Several observations of reactive chlorine have been made in different locations of China. Despite no available public datasets, the simulated results of ClNO2 and other reactive chlorine species were compared with observations throughout YRD within the same time periods, as listed in Table 3. For observations outside the YRD, we intended to demonstrate the magnitude of the results. Generally, CMAQ simulated reasonable results of reactive chlorine species that were the same order of magnitude and within the range of observations.

Fig.3.

Annual average of relative changes in major oxidants (%) due to anthropogenic chlorine emissions (EMIS_CL-BASE) and oceanic halogen emissions (EMIS_OCN-BASE)

Table 3.

The comparisons of simulated reactive chlorine species with observed concentrations in China

| Time period | Species | Location | Observations | Simulations** | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jun 20~Jul 9, 2014 | ClNO2 | Northern China Plain* | >350 at most of the nights and peaked at 2070 (pptV) | 72.9±90.3 in daily-average, peaked at 1155 | Tham et al. (2016) |

| Jul 24~Aug 27, 2014 | ClNO2 | Mt. Tai, Shandong* | 54±106 on average and 2065 on maximum (pptV) | 82.2±39.6 in daily-average, peaked at 1834 | Wang et al. (2017b) |

| Jun 11~18, 2017 | ClNO2 | Beijing* | 174.3±262.0 on average and reached 1440 on maximum (pptV) | 104.4±139.9 in daily-average, peaked at 924 | Zhou et al. (2018) |

| Sep 8~14, 2018 | ClNO2 | Hok Tsui, Hong Kong* | Peaking at 840 and 940 (pptV) | 164.0±173.0 in daily-average, peaked at 990 | Dai et al. (2020) |

| May 17~Jun 17, 2018 | HCl | Taizhou | 0.6 in average and peaked more than 1 ppbV | 0.25±0.17 in daily-average, peaked at 0.8 | Li et al. (2021a) |

| May 17~Jun 17, 2018 | Particulate Cl− | Taizhou | 2.63 in average and peaked at 9.0 μg m−3 | 1.72±1.0 in daily-average, peaked at 13.8 | Li et al. (2021a) |

| May 26~Jun 14, 2019 | ClNO2 | Changzhou | 0.15±0.20 averaged with 1-min maximum concentration of 1.3 (ppbV) | 0.15±0.18 in daily-average, peaked at 0.8 | Li et al. (2023) |

| May 26~Jun 14, 2019 | Cl2 | Changzhou | 0.026±0.036 in average with maximum of 0.52 (ppbV) | 0.018±0.012 in daily-average, peaked at 0.66 | Li et al. (2023) |

| Oct 28~Dec 4, 2019 | ClNO2 | Shanghai | 0.094±0.11 averaged with 1-min maximum of 5.7 (ppbV) | 0.25±0.11 in daily-average, peaked at 1.5 | Li et al. (2023) |

| Oct 28~Dec 4, 2019 | Cl2 | Shanghai | 0.024±0.039 in average with a maximum of 1.1 (ppbV) | 0.031±0.041 in daily-average, peaked at 0.4 | Li et al. (2023) |

| Oct 30~Nov 18, 2020 | ClNO2 | Shanghai | 1h diurnal averaged maximum of 0.16 and peaked at 0.4 (5min averaged) (ppbv) | 0.19±0.06 in daily-average, peaked at 0.34 | Lou et al. (2022) |

Note: * For observations conducted outside the YRD, results were compared with simulation results at 40 monitoring sites in the YRD.

For simulation results, values were presented in the same unit as “daily average” ± “standard deviations” and peak values during the same time slices.

BrO (bromine oxide) and IO (iodine oxide) are two critical RHS. The seasonal variation of simulated BrO and IO in HAL case was generally consistent with the results of Bry and Iy, which peaked at 0.9 and 7.1 pptV in summer, respectively. The spatial distribution of BrO and IO in different seasons were shown in Fig.S6. BrO and IO were lower in inland regions and higher at coastal areas, but they were significantly influenced by the interactions between ship-originated plumes and oceanic halogens, presenting a coincident pattern with ship tracks in SEIM. NOX emitted from shipping activities could transform BrO and IO into halogen nitrates (XNO3) which would eventually deposit onto the sea surface, serving as a sink for halogen oxide (XO) to decrease their levels. As BrO and IO both rapidly transform into XNO3 or other species, the decreasing effect of ship emissions becomes obvious (Li et al., 2021b), thus exhibiting a trajectory in line with ship tracks.

For BrO and IO, no measurements have been made in the YRD hitherto, thus we could only compare the simulation results with observations outside the domain of this study. On the other hand, previous modeling studies should also reproduce the magnitude of simulated BrO and IO and might support the results from this study. The comparisons between CMAQ simulations and available observations and simulations of BrO and IO over the ocean were listed in Table 4. Saiz-Lopez and von Glasow (2012) compiled earlier observations of BrO and reported maximum range of 0.5 to 2.0 pptV for ground-based and 3.0 to 3.6 pptV for open sea measurements. For IO, the levels observed were between 0.2 to 2.4 pptV and 3.5 pptV for land-based and cruise measurements. Other studies have reported observed BrO and IO concentrations in MBL with an order of 1 pptV (Allan et al., 2000; Mahajan et al., 2009; Peters et al., 2005; Read et al., 2008), which were generally comparable to our simulation results.

Table 4.

The comparisons of simulated BrO and IO over the ocean with observations and simulations reported from previous studies

| Species | Time period | Sources | Observation or simulation results |

CMAQ simulation results* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrO (pptV) | Jan-Feb, 2014 | Flight campaign in west Pacific1 | <0.5 to 1.7 during daytime below 500 m | 0.11 in daily-average, peaked at 0.35 |

| 4 months of 2016 | WRF-CMAQ simulations in west Pacific2 | 1.0 to 2.04 in maximum from different seasons | 0.1 to 1.0 in daily-maximum | |

| Aug, 2018 | WRF-Chem simulations in west Pacific3 | 0.45 in daytime average and 1.4 in maximum | 0.26 in daytime average, peaked at 0.97 | |

| Jul, 2019 | WRF-CMAQ simulations in the Philippine Sea4 | 0.25 in average and 1.2 in maximum | 0.14 in daily-average, peaked at 0.93 | |

| IO (pptV) | Dec, 2010-Jul, 2011 | Malaspina 2010 global circumnavigation5 | 0.4 to 1.4 in the west Pacific marine boundary layer | 0.36 to 2.07 in daily-average |

| Jan-Feb, 2015 | Cruise campaign in the Indian Southern Ocean6 | Peaked at 0.57±0.27 on 6.2°N | 0.61 in daily-maximum | |

| Aug, 2018 | WRF-Chem simulations in west Pacific3 | 1.2 in average and 2.6 in maximum at the surface | 1.9 in daily-average, peaked at 6.9 | |

| Jul, 2019 | WRF-CMAQ simulations in the Philippine Sea4 | 1.4 in average and 2.5 in maximum | 2.0 in daily-average, peaked at 7.0 |

Note: *CMAQ simulation results were averaged over the ocean from the same time slices according to observations.

CMAQ produced lower BrO levels probably due to the uncertainties in the speciation of halogen contents in sea spray aerosols and the parametrization of bromocarbon emissions. The slight underestimation of BrO from simulations was also reported in previous CMAQ halogen chemistry studies (Li et al., 2019; Sarwar et al., 2019). For IO simulations, IO levels were expected to be higher in nearshore areas due to higher bioactivity and higher outflow of O3 pollution from the coast. It should be emphasized that the comparisons were indirect due to limited observations and we urged for more relevant RHS measurements to improve model validations. Nonetheless, the level and order of magnitude of RHS simulated in this study were comparable to previous modelling studies and observations, indicating that the CMAQ model was suitable to investigate the effect of halogens on air quality in the YRD region.

3.3. Impact of halogens on atmospheric oxidation

3.3.1. Impact of halogens on major atmospheric oxidants

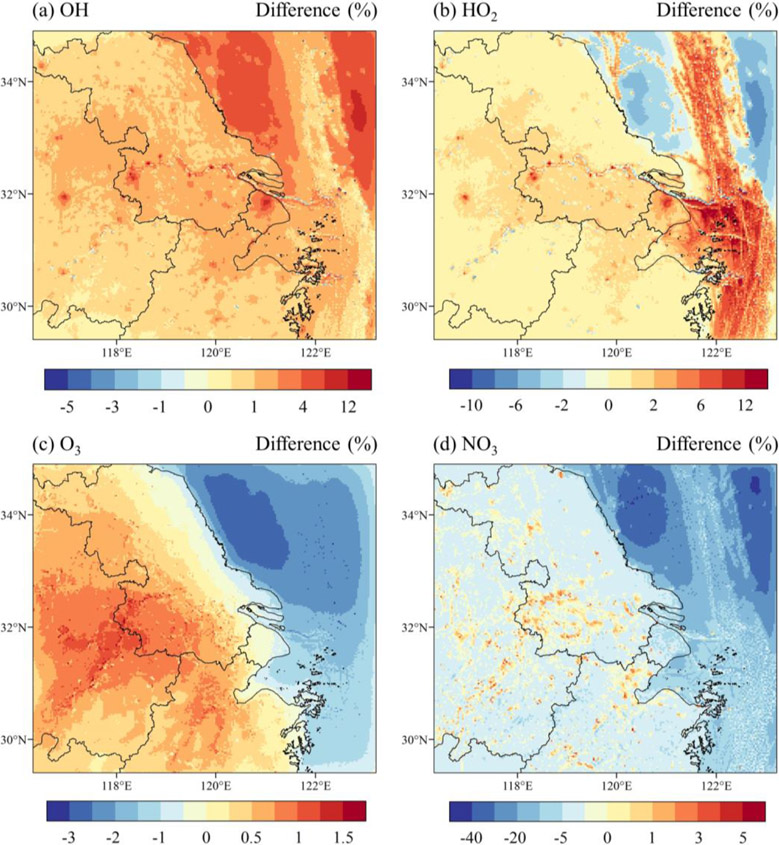

The annual average impact of halogens on individual oxidants in the YRD region were shown in Fig.2, and relative changes of oxidants (OH, HO2, O3 and NO3) derived from different emission sources of halogens (EMIS_CL and EMIS_OCN) were shown in Fig.3. Seasonal variations of changes in these oxidants were consecutively shown in Fig.S10~S13. Halogen emissions and chemistry induced a uniformly positive impact on OH radical. The highest increase of OH occurred in locations with larger anthropogenic chlorine emissions (Fig.S2) in the YRD region, which was more than 4% in annual average. Chlorine would influence OH production mainly through the reactions with VOCs to produce HOX and changes in the partitioning of HO2 and OH. Halogen-mediated changes in HO2 were consistent with OH on the land with a higher increase up to 8% in provincial capitals in the YRD region. The seasonal variation of OH and HO2 had similar patterns which peaked in summer in BASE run due to stronger solar radiation and photochemical reactions (Fig.S10 and S11). The influence on HOX was the strongest in winter, since the mixing ratio of OH and HO2 was the lowest in winter.

Fig.2.

Annual average of relative difference of simulated oxidants (%) between HAL and BASE cases

The increase of HOX due to halogens on land was primarily influenced by anthropogenic chlorine (Fig.3a, b). Although simulated bromine and iodine species on the land were non-negligible, their impact on HOX mixing ratio was overall neutral (less than ±1%), whereas they would exert a larger influence in the marine environment (Fig.3e, f). The impact of oceanic halogens (mainly bromine and iodine) on OH and HO2 presented an opposite result with increased OH up to 12% and decreased HO2 for 8%, indicating the role of halogens in changing HOX partitioning. In the marine environment, the transformation of HO2 to OH and decrease in the ratio of HO2/OH were mainly driven by iodine and bromine chemistry (Saiz-Lopez and von Glasow, 2012) and the relative changes in our study were in accordance to previous modelling studies (Mahajan et al., 2021; Sarwar et al., 2015; Stone et al., 2018). The influence of oceanic halogens on HOX along ship tracks was distinct. Relative changes in OH induced by oceanic halogens along ship tracks were weaker than that outside shipping trajectories (Fig.3e). The mixing ratio of HO2 was lower along the ship tracks in BASE case and was significantly increased due to oceanic halogens in all seasons along ship plumes. Changes of HOX along the ship plumes were complex in different pathways: (1) O3 reduction due to halogens in marine environment (Fig.2c) and hence reduced production of OH by ozone photolysis; (2) VOC oxidation by halogens along ship tracks and increased production of HO2; (3) competitions between ship-emitted NOX and atmospheric HOX.

Surface O3 was moderately increased around 1% annually in the YRD region while in marine environment O3 was decreased by 3% (Fig.2c). In coastal areas where the atmosphere was both influenced by anthropogenic chlorine and oceanic halogens, the changes of O3 became neutral, indicating that the decreasing effect of bromine and iodine on O3 is compensated for by the enhancement effect of chlorine. For seasonal variations (Fig.S12), O3 decreased by 1% along the coast in summer, covering the entire of Shanghai due to a stronger horizontal transport of emitted bromine and iodine species (Fig.S9), and decreased more than 2% in the marine environment. On the contrary, O3 was the lowest in winter and was mostly enhanced by more than 2% in the YRD region in HAL run. Chlorine emissions and chemistry were identified to aggravate O3 pollution in areas where anthropogenic activities and pollutant emissions were heavy through oxidizing VOCs to form peroxy radicals and reactions of Cl radicals and NO2 to form radical precursors ClNO2, which would both lead to O3 formation. Li et al. (2019) found a maximum O3 increment of 0.22 ppbV due to chlorine chemistry over the land of Europe in summer. Wang et al. (2019) reported a neutral to negative effect of chlorine chemistry on O3 in China, but they did not include anthropogenic chlorine emissions. For bromine and iodine impact, halogens would directly destroy O3 and reduce the level of NO2 that subsequently reduce the production of O3 (Fig.3g). Huang et al. (2021) reported a depletion in O3 by 6% over the coast line of China due to oceanic halogen emissions (bromine and iodine) and chemistry and the sharpest gradient of O3 loss occurred near the coastline offshore.

NO3 was generally reduced over the YRD region for up to 10% in annual average, and was further reduced in the marine environment (Fig.2d). The decrease in NO3 was majorly resulted from oceanic halogen emissions, while along road networks in the YRD region, NO3 mixing ratio would increase due to chlorine (Fig.3d, h). As for the seasonal variation (Fig.S13), NO3 was significantly reduced in summer even for the inland YRD region due to strong photolysis and oceanic halogen emissions. In winter, NO3 was generally increased owing to the combination effect of increasing O3 and NO2 (Fig.S12h and S14h), although its mixing ratio was relatively low. In marine environment, less decreased NO3 was marked along the ship tracks in all seasons. NOX emitted from ship plumes might compensate for the loss of NO3 but still was overwhelmed by the decreasing effect of halogens. NO3 was a nighttime radical primarily formed by the reaction of O3 and NO2, and was removed by rapid photolysis during daytime. NO3 precursors would react with HOX and RHS (OH+NO2 and XO+NO2 to form nitric acid and subsequently lost to aqueous phase) and form nitrate aerosol through heterogeneous reactions, therefore the increase of HOX by halogens could result in a general decrease in NO3. Similarly, Li et al. (2019) found a monthly average decrease of NO3 over continental Europe by 1~20 pptV in summer and NO3 was less reduced along ship trajectories due to overall halogen chemistry. Muñiz-Unamunzaga et al. (2018) reported a reduction of both NO3 and HNO3 by 20~50% and 6~10%, respectively, from marine halogens in Los Angeles during August to September of 2006.

3.3.2. Impact of halogens on atmospheric oxidation capacity

Atmospheric oxidation capacity was estimated using Equation 1 and shown in Fig.4. In the BASE case, AOC influenced by major oxidants (OH, O3, and NO3) presented a clear seasonal variation that peaked in summer with high levels of OH and O3 while rapidly declined in winter, which was in line with the seasonal variations of oxidants. For halogen-influenced AOC which included Cl radicals, denoted as HAL-AOC, was consistently enhanced by halogens between 5~20% over the YRD region and also exhibited a similar seasonal pattern in accordance to the relative changes of atmospheric oxidants in the marine environment. The strongest enhancement of HAL-AOC occurred during winter by up to 48.4%.

Fig.4.

Seasonal average of atmospheric oxidation capacity (106 molecules cm−1 s−1) in BASE case and relative changes (%) induced by halogens (HAL-AOC) between HAL and BASE cases

OH and Cl radicals are daytime oxidants while NO3 is a nighttime oxidant. O3 can exist both at night and during the day. AOC was controlled by different oxidants during a day and would exhibit a diurnal pattern. In this study, Shanghai was selected to examine the impact of overall halogen chemistry on AOC. Diurnal profile of annual average AOC was shown in Fig.S15. Daytime AOC was approximately 2.5 to 5 times higher than nighttime AOC and the dominating radical was OH in both BASE and HAL cases. AOC peaked rapidly before noon, indicating the influence of heavy traffic emissions during rush hours. Nighttime AOC was controlled by O3 and NO3 accumulated after sunset, while the former was photolyzed before noon and the latter was gradually extinguished before dawn. The increase of HAL-AOC was achieved via increasing OH and adding Cl radicals, while changes in O3 and NO3 induced by halogens were less significant (Fig.S15 and S16). Similarly, Xue et al. (2015) reported a rapidly increase of AOC in the early morning due to chlorine chemistry at a coastal site of Hong Kong.

Anthropogenic chlorine emissions from industrial processes and residential activities led to high loadings of reactive chlorine species in the YRD region. The increase of HAL-AOC (up to 46.2%) induced by chlorine emissions presented several noticeable hot spots over the YRD region that were consistent with the spatial distributions of heavy chlorine emissions (Fig.S17). The results of chlorine’s impact on AOC suggested a further investigation on anthropogenic halogen emissions as they would exert influences on VOCs and NOX. In polluted areas, O3 formation was controlled by its precursors, VOC or NOX, and the impact of HAL-AOC would be closely related to O3 formation regime. Li et al. (2020) found that AOC increased in VOC and mixed-limited regions while AOC declined in NOX-limited regions over China. Chen et al. (2024) reported a higher AOC in summer and O3 formation was controlled by both VOCs and NOX at Ningde in Fujian Province in China.

Oceanic emissions of halogens would produce nonnegligible loadings of halogens (Bry and Iy) in marine environment and along the coast of the YRD region. Oceanic halogens resulted in the increase of HAL-AOC through enhancing OH radical levels which peaked in spring by up to 23% over the ocean and more than 5% along the coast. Therefore, influence of ocean-emitted halogens cannot be ignored and their emissions should be included in air quality modelling studies in coastal areas of China.

3.4. Contributions of halogens influencing individual oxidants through process analysis

3.4.1. OH

In this study, the integrated reaction rate (IRR) provided by process analysis module within CMAQ was used to investigate the strengths of different pathways influencing individual oxidants by different halogen species. IRR can calculate production rates of chemical species from different reactions (i.e., production rate of O3 from halogens) (Jeffries and Tonnesen, 1994). Chlorine, bromine and iodine were isolated by conducting sensitivity simulations. The annual average of absolute changes of production rate of OH (ΔPOH) were shown in Fig.5a. In our study, pathways of OH production were distributed into 3 major sources: (1) from O3 photolysis (reactions of O(1D) + H2O to produce OH, here denoted as ΔPOH_O3); (2) from HO2 conversion (HO2 + NO3, O3, etc., ΔPOH_HO2); (3) from hypohalous acid photolysis (for example HOI photolysis to produce I and OH radicals, ΔPOH_HAL). In accordance to changes in the OH radical mixing ratio, halogen impacts on the production of OH throughout the domain remained positive. The increase of POH was achieved mainly through both HO2 and hypohalous acid enhancement by chlorine on lands while hypohalous acid photolysis enhanced OH radical production over the ocean that compensated for the loss of HO2 by marine halogens (Fig.5b~d). Changes of ΔPOH from O3 and other sources were less significant compared to the other pathways (with an annual average of −0.71 and 0.83 pptV, respectively), hence they were not included in the further discussion (Fig.S18a). The annual POH_O3 was reduced by iodine up to 28 pptV (1.5 pptV in annual average and peaked in summer for 4.2 pptV), indicating a combination effect of enhanced O3 deposition (Chang et al., 2004; Pound et al., 2020) and destruction by iodine chemistry, especially in the marine environment (Fig.S18b). The decrease of POH in O3 photolysis pathway by iodine would result in a total reduction of ΔPOH_O3 from 2~8 pptV in marine environment in comparison of HAL and BASE cases.

Fig.5.

Annual average of absolute changes of (a) total Poh and (b-d) decomposed pathways of POH (pptV) between HAL and BASE cases

We further probed into the impact exerted on POH through pathways of HO2 conversions and hypohalous acid photolysis by individual halogens. Since the most distinct season was summer with the highest oxidative radical mixing ratio and oceanic halogen emissions, we focused on the analysis of changes in OH production in summertime. Seasonal variations of monthly average of ΔPOH_HO2 and ΔPOH_HAL by separate halogen species were shown in Fig.6 and 7. For chlorine chemistry, POH from HO2 pathway was enhanced by up to 479 pptV in summer and 213 pptV in winter. The largest increase in POH_HO2 by Cl chemistry occurred where anthropogenic emissions were higher, thus illustrating several hot spots in the city clusters such as Shanghai, Nanjing and Hefei, over the YRD region. Chlorine could oxidize VOCs emitted from anthropogenic sources including ship plumes and produce HO2 and RO2 radicals, therefore exerting a positive impact on POH from HO2 conversion pathway. The production of OH from hypohalous acid photolysis was also intensified since the chlorine emission included HOCl in this study, but with a smaller magnitude. ΔPOH_HAL by chlorine peaked in summer at 86 pptV and 17 pptV in winter, and the spatial distribution of ΔPOH_HAL was also in line with the intensity of chlorine emission inventory. HOCl was produced from both primary emission and the reaction of HO2 with ClO in the area and would ultimately photolyzed to produce OH and Cl radicals.

Fig.6.

Monthly average changes in POH from HO2 conversion pathway (ΔPOH_HO2) (pptV) induced by different halogens in summer and winter

Fig.7.

Monthly average changes in POH from hypohalous acid photolysis pathway (ΔPOH_HAL) (pptV) induced by different halogens in summer and winter

The changes in POH by bromine and iodine from two pathways separately were consistent, but their combination effect on total ΔPOH was the opposite especially in summertime marine environment (Fig.S19). Iodine would aggravate the production of OH more than 60 pptV over the ocean in summer while bromine exhibited a relatively weaker impact on ΔPOH with a negative effect outside ship tracks. For HO2 conversion pathway, changes in POH_HO2 represented the indirect impact by halogens as we focused on the reactions of HO2 with NO, O3, and etc. Bromine and iodine could both inhibit direct HO2 conversion to OH in marine environment by competition with NO and O3 to consume HO2 as illustrated in Fig.S11. The decrease in POH_HO2 by iodine was higher than bromine (up to 134 and 10 pptV, respectively) and remained negative along the coast. ΔPOH_HO2 was strengthened by 10~50 pptV along the ship tracks, which was probably due to the increased ship-emitted NOX and the formation of HO2 through reactions of VOCs with oceanic halogens (Li et al., 2021b). The photolysis of hypohalous acid was another contributor to the increase of POH which was mainly resulted from iodine chemistry because of the emissions of oceanic HOI and I2. The increase of ΔPOH_HAL by iodine could peak at 277 pptV in the coastal area in summer and 3.8 pptV for bromine due to higher biogenic activities. Along ship tracks where NOX emissions were elevated, the formation of hypohalous acid was suppressed by NO radicals through lowering HO2 concentrations or serving as a sink for XO and subsequently would reduce POH in hypohalous acid photolysis pathway (Simpson et al., 2015).

In regard to the pathways of ΔPOH influenced by individual halogens, the increase of POH was achieved through both strengthened HO2 conversion and HOCl photolysis in the YRD region by chlorine chemistry. For bromine and iodine chemistry, XO would shift the HOX partitioning to OH by consuming HO2 to produce hypohalous acid and further photolyzed to produce OH radicals. The influence of bromine on POH was generally weaker than iodine probably because of the lower reactivity of BrO with HO2 (Whalley et al., 2010). Therefore, iodine chemistry would uniformly increase POH in most of the areas where bromine could not. The decrease of POH in Shanghai indicated further investigations on the impact of atmospheric chemistry by iodine were needed especially in coastal areas (Fig.S19c). Inorganic iodine species (mostly HOI and I2) were released to the atmosphere that were correlated with the amount of O3 deposition to the ocean (Cuevas et al., 2018; Legrand et al., 2018). Oceanic iodine emissions were subjected to increase in the future as feedbacks of increasing anthropogenic O3 pollutions and subsequently would exert further influences on O3 and other pollutants in coastal areas.

3.4.2. O3 and NO3

Halogens could cause direct O3 depletion through catalytic cycling or indirect effect on O3 precursors through complex reactions which might cause opposite influences on the O3 concentration, resulting in a rather neutral impact on O3 by comprehensive halogen chemistry. IRR was used to examine the pathways of O3 loss (LO3) induced by direct halogen destruction and production (PO3) influenced by halogens on its precursors. The pathways of O3 concentration changes were shown in Fig.8. Halogen induced annual average direct O3 destruction reached more than 600 pptV in ocean areas and more than 50 pptV along the coast, while halogen could have an obvious direct influence on O3 over Shanghai. The enhanced O3 loss rate was substantially contributed from marine iodine emissions for up to 90% of the O3 destruction (Fig.S20c). Reactive iodine species were activated through decomposition of natural iodocarbons and ocean surface reaction of iodide ions and O3 to produce inorganic precursors, HOI and I2 (MacDonald et al., 2014). The rate coefficient of IO self-reaction was so high that it could produce OIO and I2O2 through the reaction of IO + IO, and OIO could be further photolyzed to produce I and O2, increasing the efficiency of iodine cycling and subsequent O3 depletion (Saiz-Lopez and von Glasow, 2012). Therefore, iodine species dominated the depletion rate of O3. Although the accordance with anthropogenic chlorine emission hot spots indicated the role of chlorine to destroy O3, reactions with hydrocarbons could predominate other than O3 depleting pathway and the magnitude of O3 loss rate by chlorine was incomparable to that of iodine (Simpson et al., 2015). The indirect influence on O3 production rate by halogens was generally positive over the land and negative over the ocean, which could be attributed to anthropogenic chlorine and oceanic halogen sources, respectively (Fig.S21). The complex impact on O3 precursors by halogens as well as cross halogen reactions required a further elaboration in the modelling study which could be improved in the future. For the unusual decrease of O3 production rate in Shanghai (Fig.S21a), one possible reason was that Shanghai was a VOC-limited region where the consumption of VOC by chlorine could lead to a decrease in O3, presenting a similar hot spot with the RO2 production by chlorine (Fig.S22). Several observation-based modelling studies reported that Shanghai was usually a VOC-limited region during different time periods and was gradually changing to a transition regime in 2020 (Wang et al., 2017a; Wang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2020).

Fig.8.

Annual average changes in (a) O3 destructions (pptV) induced by halogens and (b) indirect O3 production rates induced by halogens between HAL and BASE cases

NO3 is a nocturnal radical formed from the reaction of NO2 and O3. Annual average changes in NO3 production rate (PNO3) induced by halogens were shown in Fig.9. The increase of NO3 production rate over the YRD region by halogens was somewhat similar to that of O3 since the production of NO3 was related to its precursors NO2 and O3. Chlorine would increase the production of NO3 up to 19.3 pptV (more than 4 pptV in urban areas) by enhancing O3 production and complex interactions with NOX. On the contrary, the decrease in PNO3 (2.3 pptV in average and −20 pptV in maximum) was achieved by both NO2 and O3 reduction due to iodine chemistry (Fig.9d and Fig.S23), and bromine exert a rather neutral effect on PNO3 (less than 2 pptV in general) compared to that of chlorine and iodine. The effect of comprehensive halogen chemistry on PNO3 was weaker than the sum of individual halogens, probably due to the cross halogen reactions since the reaction rate of these cross reactions were an order of magnitude faster than that of self-reactions (Simpson et al., 2015). Notably, the significant decrease of NO3 production in Shanghai implied a further study on the chemical reactions between halogens and NOX in similar coastal areas with air pollutions. Total loss rates of NO3 were 4~7 times higher than the production rate. The changes of NO3 in this study might be resulted from complex combination of different pathways: (1) O3 and NO2 were both influenced by halogens over the YRD region (Fig.S23); (2) halogens would react directly with NO3 and reduce its level; (3) complex changes of NOX induced by halogens, including NO/NO2 partitioning, removing NO2 into halogen nitrates, and forming radical precursors such as ClNO2 (Simpson et al., 2015). Note that we included in-line DMS (dimethyl sulfide) emission parameterization for marine halogen emissions revised by Zhao et al. (2021) that might also serve as a sink for marine and coastal NO3 (Andreae, 1985).

Fig.9.

Annual average changes in NO3 production (pptV) induced by different halogen species

4. Conclusions

In this study, the WRF-CMAQ model with high-resolution and comprehensive halogen chemistry were conducted to simulate and investigate the impact of halogen emissions on atmospheric oxidants over the YRD region in China. Changes in major atmospheric oxidants (OH, HO2, O3 and NO3) affected by halogens resulted in the increase of atmospheric oxidation capacity by 5.1% annually. AOC could reach more than 20% in several cities over the YRD region. Daytime OH radical was enhanced by 7.5% on diurnal average while nighttime NO3 radical was reduced by 4.4% and changes in diurnal O3 remained neutral. Contributions of OH toward AOC was approximately 2 times of the sum of O3 and NO3, and chlorine radical also exerted non-negligible influence (−5.7%) on aggravating daily AOC over the YRD region. Specifically, the contributions of anthropogenic chlorine emissions on the atmospheric oxidants were up to 16.4% for OH, 19.4% for HO2, 2.2% for O3 and 6.5% for NO3 in populated cities over the YRD. Despite the general decrease of NO3 radical due to halogen chemistry, anthropogenic chlorine emissions caused an annual increase of AOC by 3.0% and reached 46.2% in the YRD. Chlorine also contributed 58.8% to the increase of AOC in the research area.

IRR was applied to investigate pathways of oxidative radicals controlled by separate halogens. For OH radical, POH was majorly enhanced through the conversion of HO2 and hypohalous acid photolysis pathways induced by halogens. Specifically, chlorine accounted for both pathways while bromine and iodine contributed to POH mainly through converting HO2 into hypohalous acid. In regard to O3, chlorine contributed most of the increase in O3 production rate by influencing O3 precursors. The pathway of direct O3 destruction by halogens was also evaluated and iodine accounted for the most while chlorine and bromine presented a mild increase in destroying O3. Changes in the production rate of NO3 had a similar pattern to that of O3 as chlorine increased its precursors while iodine chemistry influenced the opposite. The sharp decrease of NO3 in Shanghai suggested further investigations into the impact of the reaction between DMS and NO3.

We acknowledge the possible uncertainties lay in this modelling study. For the emission inventories, the uncertainties in anthropogenic chlorine emissions adopted in this study come from industrial processes and activity data (Yi et al., 2021), and more local emission measurements and observations for chlorine precursors are required. The parameterization of halocarbon emission rates using chl-α data from MODIS observations may not reproduce the variations in a specific region since the interpolation from coarse (9km) to fine (3km) could cause biases. Moreover, recently developed halogen emission inventories besides chlorine species, such as iodide inventories and anthropogenic bromine inventories based on emissions factors and machine-learning (Sherwen et al. (2019); Li et al. (2021c)) could be adopted in future studies. The results in this study indicates a nonnegligible influence on the atmosphere by iodine and bromine, though their emissions are less comparable to that of chlorine and may be underrated. For halogen chemistry scheme, incomplete reactions due to calculation efficiency may exert limitations on our simulations. For example, several heterogenous reactions of bromine species from Fernandez et al. (2014) are excluded due to modeling uncertainties. The chemical reactions of iodine oxide photolysis and heterogeneous uptake rates of halogen species on aerosols remain uncertain in different simulation and observations studies (Badia et al., 2019; Saiz-Lopez et al., 2014; Sarwar et al., 2019). Though simple parameterizations with constant uptake coefficients of halogens in this model report acceptable simulation results, the update of halogen chemistry is still needed to improve model performances and close the gap between simulations and observations, especially for iodine species. A previous observation study suggests a higher uptake coefficient of HOI and recycling rate of interhalogen product species, which results in higher ozone loss (Tham et al., 2021). Despite the noted uncertainties, this comprehensive process analysis with sensitivity simulations revealed the different roles of individual halogens in the increase of atmospheric oxidation capacity in the YRD region.

Oceanic halogen emissions in coastal areas would be affected in response to anthropogenic activities since the activation of RHS was closely related to NOX emissions and O3 levels in the area. Meanwhile, industrial processes and residential activities (i.e., crop straw burning) could also release halogens. As a mega-city and one of the largest ports in the world, air quality in Shanghai and its surrounding city-clusters in the YRD would be affected by halogens since elevated AOC inevitably influences the production of secondary air pollutants. We identified the potential effect of halogens on air quality and recommend considering of chemical interactions between anthropogenic emissions and RHS on formulating air quality policies and regulations. A recent modeling study revealed that shipping emissions might enhance the burden of atmospheric RHS and in turn affect air pollutants (Li et al., 2021b). We propose regulations on low-chlorine fuels and disinfectants used by vessels besides existing lower-sulfur fuel policies (Zhu and Wang, 2021). Shore power facilities during ship berthing incorporating clean energy are also recommended for reducing air pollution in ports to decrease the feedbacks on RHS activation by NOX and O3. Price subsidies by the government may improve the utilization rate of shore power, and the cultivations on environmental awareness for both consumers and producers are suggested. Halocarbons emitted from seawater are influenced by anthropogenic inputs (Qi et al., 2023), therefore potential regulations on colored or fluorescent dissolved organic matter in coastal water are needed. Finally, further field, laboratory, and theoretical studies are needed for future studies evaluating the impacts of halogen chemistry on air quality and for assessing air quality policy implications in the YRD region.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The simulations were conducted on the π 2.0 cluster supported by the Center for High Performance Computing at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. We acknowledge Dr. Li Li at School of Environmental and Chemical Engineering, Shanghai University for providing data support of anthropogenic chlorine emission inventories. We also acknowledge Dr. Qinyi Li at Hong Kong Polytechnic University for valuable comments and suggestions, which offered great help to improve our methodology.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42050105).

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the U.S. EPA. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

References

- Allan BJ, McFiggans G, Plane JMC, et al. , 2000. Observations of iodine monoxide in the remote marine boundary layer. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 105, 14363–14369. 10.1029/1999jd901188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An J, Huang Y, Huang C, et al. , 2021. Emission inventory of air pollutants and chemical speciation for specific anthropogenic sources based on local measurements in the Yangtze River Delta region, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys 21, 2003–2025. 10.5194/acp-21-2003-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae MO, 1985. Dimethyl sulfide in the marine atmosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research 90, 12891–12900. 10.1029/JD090iD07p12891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R, Baulch DL, Cox RA, et al. , 2006. Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume II - gas phase reactions of organic species. Atmos. Chem. Phys 6, 3625–4055. 10.5194/acp-6-3625-2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Badia A, Reeves CE, Baker AR, et al. , 2019. Importance of reactive halogens in the tropical marine atmosphere: a regional modelling study using WRF-Chem. Atmos. Chem. Phys 19, 3161–3189. 10.5194/acp-19-3161-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W, Heikes BG, Lee M, 2004. Ozone deposition to the sea surface: chemical enhancement and wind speed dependence. Atmospheric Environment 38, 1053–1059. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2003.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Liu T, Chen J et al. , 2024. Atmospheric oxidation capacity and O3 formation in a coastal city of southeast China: Results from simulation based on four-season observation. Journal of Environmental Sciences 136, 68–80. 10.1016/j.jes.2022.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Tang H, He L, et al. , 2022. Co-effect assessment on regional air quality: A perspective of policies and measures with greenhouse gas reduction potential. Science of The Total Environment 851, 158119. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas CA, Maffezzoli N, Corella JP, et al. , 2018. Rapid increase in atmospheric iodine levels in the North Atlantic since the mid-20th century. Nature Communications 9, 1452. 10.1038/s41467-018-03756-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Liu Y, Wang P, et al. , 2020. The impact of sea-salt chloride on ozone through heterogeneous reaction with N2O5 in a coastal region of south China. Atmospheric Environment 236, 117604. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elshorbany YF, Kurtenbach R, Wiesen P et al. , 2009. Oxidation capacity of the city air of Santiago, Chile. Atmos. Chem. Phys 9, 2257–2273. 10.5194/acp-9-2257-2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan S, Li Y, 2022. The impacts of marine-emitted halogens on OH radicals in East Asia during summer. Atmos. Chem. Phys 22, 7331–7351. 10.5194/acp-22-7331-2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez RP, Salawitch RJ, Kinnison DE, et al. , 2014. Bromine partitioning in the tropical tropopause layer: implications for stratospheric injection. Atmos. Chem. Phys 14, 13391–13410. 10.5194/acp-14-13391-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Lu X, Fung JCH, et al. , 2021. Effect of bromine and iodine chemistry on tropospheric ozone over Asia-Pacific using the CMAQ model. Chemosphere 262, 127595. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries HE, Tonnesen S, 1994. A comparison of two photochemical reaction mechanisms using mass balance and process analysis. Atmospheric Environment 28, 2991–3003. 10.1016/1352-2310(94)90345-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig TK, Volkamer R, Baidar S, et al. , 2017. BrO and inferred Bry profiles over the western Pacific: relevance of inorganic bromine sources and a Bry minimum in the aged tropical tropopause layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys 17, 15245–15270. 10.5194/acp-17-15245-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lary DJ, 1997. Catalytic destruction of stratospheric ozone. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 102, 21515–21526. 10.1029/97JD00912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand M, McConnell JR, Preunkert S, et al. , 2018. Alpine ice evidence of a three-fold increase in atmospheric iodine deposition since 1950 in Europe due to increasing oceanic emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, 12136–12141. 10.1073/pnas.1809867115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Huang DD, Nie W, et al. , 2023. Observation of nitrogen oxide-influenced chlorine chemistry and source analysis of Cl2 in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Atmospheric Environment 306, 119829. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2023.119829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhang N, Wang P, et al. , 2021a. Impacts of chlorine chemistry and anthropogenic emissions on secondary pollutants in the Yangtze river delta region. Environmental Pollution 287, 117624. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Liu H, Geng G, et al. , 2017. Anthropogenic emission inventories in China: a review. National Science Review 4, 834–866. 10.1093/nsr/nwx150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Badia A, Fernandez RP, et al. , 2021b. Chemical Interactions Between Ship-Originated Air Pollutants and Ocean-Emitted Halogens. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 126, e2020JD034175. 10.1029/2020JD034175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Badia A, Wang T, et al. , 2020. Potential Effect of Halogens on Atmospheric Oxidation and Air Quality in China. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 125, e2019JD032058. 10.1029/2019JD032058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Borge R, Sarwar G, et al. , 2019. Impact of halogen chemistry on summertime air quality in coastal and continental Europe: application of the CMAQ model and implications for regulation. Atmos. Chem. Phys 19, 15321–15337. 10.5194/acp-19-15321-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Fu X, Peng X, et al. , 2021c. Halogens Enhance Haze Pollution in China. Environmental Science & Technology 55, 13625–13637. 10.1021/acs.est.1c01949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhang L, Wang T et al. , 2016. Impacts of heterogeneous uptake of dinitrogen pentoxide and chlorine activation on ozone and reactive nitrogen partitioning: improvement and application of the WRF-Chem model in southern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys 16, 14875–14890. 10.5194/acp-16-14875-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Fu M, Jin X, et al. , 2016. Health and climate impacts of ocean-going vessels in East Asia. Nature Climate Change 6, 1037–1041. 10.1038/nclimate3083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Meng Z-H, Lv Z-F, et al. , 2019. Emissions and health impacts from global shipping embodied in US-China bilateral trade. Nature Sustainability 2, 1027–1033. 10.1038/s41893-019-0414-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Warner TT, Bowers JF, et al. , 2008. The Operational Mesogamma-Scale Analysis and Forecast System of the U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command. Part I: Overview of the Modeling System, the Forecast Products, and How the Products Are Used. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 47, 1077–1092. 10.1175/2007jamc1653.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lou S, Tan Z, Gan G, et al. , 2022. Observation based study on atmospheric oxidation capacity in Shanghai during late-autumn: Contribution from nitryl chloride. Atmospheric Environment 271, 118902. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2021.118902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Guo S, Tan Z, et al. , 2019. Exploring atmospheric free-radical chemistry in China: the self-cleansing capacity and the formation of secondary air pollution. Natl Sci Rev 6, 579–594. 10.1093/nsr/nwy073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luecken DJ, Yarwood G, Hutzell WT, 2019. Multipollutant modeling of ozone, reactive nitrogen and HAPs across the continental US with CMAQ-CB6. Atmospheric Environment 201, 62–72. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald SM, Gómez Martín JC, Chance R, et al. , 2014. A laboratory characterisation of inorganic iodine emissions from the sea surface: dependence on oceanic variables and parameterisation for global modelling. Atmos. Chem. Phys 14, 5841–5852. 10.5194/acp-14-5841-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AS, Li Q, Inamdar S, et al. , 2021. Modelling the impacts of iodine chemistry on the northern Indian Ocean marine boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys 21, 8437–8454. 10.5194/acp-21-8437-2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AS, Oetjen H, Saiz-Lopez A, et al. , 2009. Reactive iodine species in a semi-polluted environment. Geophysical Research Letters 36. 10.1029/2009GL038018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AS, Tinel L, Hulswar S, et al. , 2019. Observations of iodine oxide in the Indian Ocean marine boundary layer: A transect from the tropics to the high latitudes. Atmospheric Environment: X 1, 100016. 10.1016/j.aeaoa.2019.100016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz-Unamunzaga M, Borge R, Sarwar G, et al. , 2018. The influence of ocean halogen and sulfur emissions in the air quality of a coastal megacity: The case of Los Angeles. Science of The Total Environment 610-611, 1536–1545. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osthoff HD, Roberts JM, Ravishankara AR, et al. , 2008. High levels of nitryl chloride in the polluted subtropical marine boundary layer. Nature Geoscience 1, 324–328. 10.1038/ngeo177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrella JP, Jacob DJ, Liang Q, et al. , 2012. Tropospheric bromine chemistry: implications for present and pre-industrial ozone and mercury. Atmos. Chem. Phys 12, 6723–6740. 10.5194/acp-12-6723-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C, Pechtl S, Stutz J, et al. , 2005. Reactive and organic halogen species in three different European coastal environments. Atmos. Chem. Phys 5, 3357–3375. 10.5194/acp-5-3357-2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pound RJ, Sherwen T, Helmig D, et al. , 2020. Influences of oceanic ozone deposition on tropospheric photochemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys 20, 4227–4239. 10.5194/acp-20-4227-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prados-Roman C, Cuevas CA, Hay T, et al. , 2015. Iodine oxide in the global marine boundary layer. Atmos. Chem. Phys 15, 583–593. 10.5194/acp-15-583-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Q-Q, Yang G-P, Yang B, et al. , 2023. Spatiotemporal distributions and oceanic emissions of short-lived halocarbons in the East China Sea. Science of The Total Environment 893, 164879. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Ying Q, Wang S, et al. , 2019. Significant impact of heterogeneous reactions of reactive chlorine species on summertime atmospheric ozone and free-radical formation in north China. Science of The Total Environment 693, 133580. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read KA, Mahajan AS, Carpenter LJ, et al. , 2008. Extensive halogen-mediated ozone destruction over the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Nature 453, 1232–1235. 10.1038/nature07035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Lopez A, Fernandez RP, Ordóñez C, et al. , 2014. Iodine chemistry in the troposphere and its effect on ozone. Atmos. Chem. Phys 14, 13119–13143. 10.5194/acp-14-13119-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saiz-Lopez A, von Glasow R, 2012. Reactive halogen chemistry in the troposphere. Chemical Society Reviews 41, 6448–6472. 10.1039/C2CS35208G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar G, Gantt B, Foley K, et al. , 2019. Influence of bromine and iodine chemistry on annual, seasonal, diurnal, and background ozone: CMAQ simulations over the Northern Hemisphere. Atmospheric Environment 213, 395–404. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar G, Gantt B, Schwede D, et al. , 2015. Impact of Enhanced Ozone Deposition and Halogen Chemistry on Tropospheric Ozone over the Northern Hemisphere. Environmental Science & Technology 49, 9203–9211. 10.1021/acs.est.5b01657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar G, Simon H, Bhave P, et al. , 2012. Examining the impact of heterogeneous nitryl chloride production on air quality across the United States. Atmos. Chem. Phys 12, 6455–6473. 10.5194/acp-12-6455-2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwen T, Chance RJ, Tinel L et al. , 2019. A machine-learning-based global sea-surface iodide distribution. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 11, 1239–1262. 10.5194/essd-11-1239-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson WR, Brown SS, Saiz-Lopez A, et al. , 2015. Tropospheric Halogen Chemistry: Sources, Cycling, and Impacts. Chemical Reviews 115, 4035–4062. 10.1021/cr5006638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D, Sherwen T, Evans MJ, et al. , 2018. Impacts of bromine and iodine chemistry on tropospheric OH and HO2: comparing observations with box and global model perspectives. Atmos. Chem. Phys 18, 3541–3561. 10.5194/acp-18-3541-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Lu K, Jiang M, et al. , 2019. Daytime atmospheric oxidation capacity in four Chinese megacities during the photochemically polluted season: a case study based on box model simulation. Atmos. Chem. Phys 19, 3493–3513. 10.5194/acp-19-3493-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tham YJ, He X-C, Li Q, et al. , 2021. Direct field evidence of autocatalytic iodine release from atmospheric aerosol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2009951118. https://doi.org/doi: 10.1073/pnas.2009951118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tham YJ, Wang Z, Li Q, et al. , 2016. Significant concentrations of nitryl chloride sustained in the morning: investigations of the causes and impacts on ozone production in a polluted region of northern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys 16, 14959–14977. 10.5194/acp-16-14959-2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DS, Ruiz LH, 2017. Secondary organic aerosol from chlorine-initiated oxidation of isoprene. Atmos. Chem. Phys 17, 13491–13508. 10.5194/acp-17-13491-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Xue L, Brimblecombe P, et al. , 2017a. Ozone pollution in China: A review of concentrations, meteorological influences, chemical precursors, and effects. Science of The Total Environment 575, 1582–1596. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Parrish DD, Wang S, et al. , 2022. Long-term trend of ozone pollution in China during 2014–2020: distinct seasonal and spatial characteristics and ozone sensitivity. Atmos. Chem. Phys 22, 8935–8949. 10.5194/acp-22-8935-2022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Jacob DJ, Eastham SD, et al. , 2019. The role of chlorine in global tropospheric chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys 19, 3981–4003. 10.5194/acp-19-3981-2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang W, Tham YJ, et al. , 2017b. Fast heterogeneous N2O5 uptake and ClNO2 production in power plant and industrial plumes observed in the nocturnal residual layer over the North China Plain. Atmos. Chem. Phys 17, 12361–12378. 10.5194/acp-17-12361-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whalley LK, Furneaux KL, Goddard A, et al. , 2010. The chemistry of OH and HO2 radicals in the boundary layer over the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Atmos. Chem. Phys 10, 1555–1576. 10.5194/acp-10-1555-2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Womack CC, Chace WS, Wang S, et al. , 2023. Midlatitude Ozone Depletion and Air Quality Impacts from Industrial Halogen Emissions in the Great Salt Lake Basin. Environmental Science & Technology 57, 1870–1881. 10.1021/acs.est.2c05376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue LK, Saunders SM, Wang T, et al. , 2015. Development of a chlorine chemistry module for the Master Chemical Mechanism. Geosci. Model Dev 8, 3151–3162. 10.5194/gmd-8-3151-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wang T, Xia M, et al. , 2018. Abundance and origin of fine particulate chloride in continental China. Science of the Total Environment 624, 1041–1051. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi X, Yin S, Huang L, et al. , 2021. Anthropogenic emissions of atomic chlorine precursors in the Yangtze River Delta region, China. Science of The Total Environment 771, 144644. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Xu J, Huang Q, et al. , 2020. Precursors and potential sources of ground-level ozone in suburban Shanghai. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering 14, 92. 10.1007/s11783-020-1271-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Li Q, Wang T, et al. , 2017. Combined impacts of nitrous acid and nitryl chloride on lower-tropospheric ozone: new module development in WRF-Chem and application to China. Atmos. Chem. Phys 17, 9733–9750. 10.5194/acp-17-9733-2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Sarwar G, Gantt B et al. , 2021. Impact of dimethylsulfide chemistry on air quality over the Northern Hemisphere. Atmospheric Environment 244, 117961. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Tong D, Li M, et al. , 2018. Trends in China's anthropogenic emissions since 2010 as the consequence of clean air actions. Atmos. Chem. Phys 18, 14095–14111. 10.5194/acp-18-14095-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Zhao J, Ouyang B, et al. , 2018. Production of N2O5 and ClNO2 in summer in urban Beijing, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys 18, 11581–11597. 10.5194/acp-18-11581-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Wang J, 2021. The effects of fuel content regulation at ports on regional pollution and shipping industry. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 106, 102424. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jeem.2021.102424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.