Best medical treatment for peripheral arterial disease, including managing hypertension and diabetes, reduces morbidity and mortality and can obviate the need for invasive intervention

One in five of the middle aged (65-75 years) population of the United Kingdom have evidence of peripheral arterial disease on clinical examination, although only a quarter of them have symptoms. The most common symptom is muscle pain in the lower limbs on exercise—intermittent claudication.1 Invasive interventions (angioplasty, stenting, surgery) undoubtedly have a role in the management of peripheral arterial disease. However, in common with coronary artery disease, the morbidity and mortality associated with peripheral arterial disease can be greatly reduced, and the results of intervention significantly improved, by the institution of so called “best medical treatment,” much of which can be implemented in primary care.

Summary points

Diagnosis of peripheral arterial disease is based mainly on the history, with examination and ankle brachial pressure index being used to confirm and localise the disease

Peripheral arterial disease is a marker for systemic atherosclerosis; the risk to the limb in claudication is low, but the risk to life is high

Patients with intermittent claudication should initially be treated with “best medical treatment”; some patients may be candidates for percutaneous angioplasty, but this treatment is not based on evidence

Patients should be referred to a vascular surgeon if there is doubt about the diagnosis or evidence of aortoiliac disease or if the patient has not responded to best medical treatment or has severe disease

Sources and selection criteria

We used Medline to identify recent reviews and articles on the epidemiology, assessment, and treatment of peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication, by using the terms “intermittent claudication,” “peripheral arterial disease,” and “peripheral vascular disease.” We also consulted standard textbooks, national and local guidelines, and service frameworks.

Diagnosis and assessment

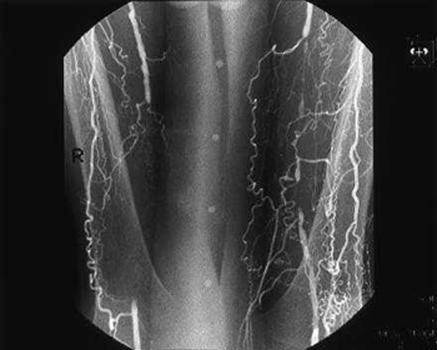

A diagnosis of intermittent claudication can usually be made on the basis of the history—the Edinburgh claudication questionnaire is highly specific (91%) and sensitive (99%) for the condition (table A on bmj.com).2 The differential diagnosis includes both venous and neurogenic claudication (table 1). Examination usually reveals weak or absent pulses, and further investigations (duplex ultrasonography, angiography) are usually reserved for the small minority of patients in whom invasive intervention is being considered (fig 1).

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of intermittent claudication

| Characteristic

|

Intermittent claudication

|

Venous claudication

|

Nerve root pain

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of pain | Cramping | “Bursting” | Electric shock-like |

| Onset | Gradual, consistent | Gradual, can be immediate | Can be immediate, inconsistent |

| Relieved by | Standing still | Elevation of leg | Sitting down, bending forward |

| Location | Muscle groups (buttock, thigh, calf) | Whole leg | Poorly localised, can affect whole leg |

| Legs affected | Usually one | Usually one | Often both |

Figure 1.

Angiogram showing bilateral femoral artery occlusions in a patient with claudication

The rationale for best medical treatment

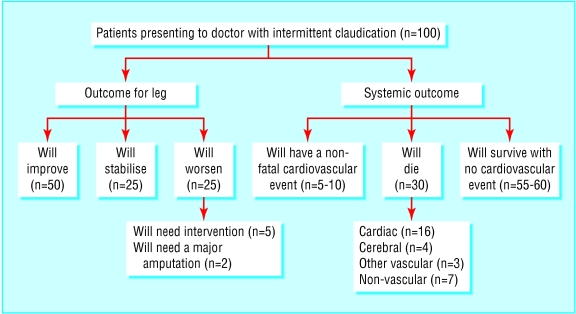

Contrary to popular belief, the risk of a person with claudication progressing to critical limb ischaemia and needing amputation is low (<1% a year). However, the risk of death, mainly from coronary and cerebrovascular events, is high (5-10% a year), some three to four times greater than that of an age and sex matched population without claudication (fig 2 and fig A on bmj.com15). Initial management should consist of modification of vascular risk factors and implementation of best medical treatment in the expectation that this will extend life, reduce still further the risk of critical limb ischaemia, and improve the patient's functional status. Only when best medical treatment has been instituted and given sufficient time to take effect should endovascular or surgical intervention be considered, as most patients' symptoms improve with best medical treatment to a point where invasive intervention is no longer needed.3 Best medical treatment is beneficial even in patients who eventually need invasive treatment, as the safety, immediate success, and durability of intervention is greatly improved in patients who adhere to best medical treatment.4,5

Figure 2.

Outcome for patients with intermittent claudication over five years14

Components of best medical treatment

Table 2 summarises the components of best medical treatment and their effects on peripheral arterial disease, vascular events, and mortality.

Table 2.

Components of best medical treatment in peripheral arterial disease

| Component

|

Recommendation

|

Effect on mortality or vascular events

|

Effect on peripheral arterial disease

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking cessation | Repeated advicew1* Nicotine replacement therapy or bupropionw2,w3* Behavioural therapy (smoking cessation classes)w4* |

Cessation leads to a reduction in 10 year mortality from 54% to 18%w5 | Rest pain in 0% of quitters compared with 16% of continued smokers at seven yearsw5 |

| Reduction in cholesterol | All patients to be on a statin to achieve a 25% reduction in cholesterolw6 Additional treatment may be needed if HDL is low or triglycerides are high (referral to lipid clinic) |

RR=0.81 (0.72 to 0.87) for major vascular event (myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularisation)w6 | No evidence of clinical benefitw7 |

| Antiplatelet agent | Aspirin 75 mg dailyw8 Clopidogrel 75 daily if intolerant of aspirinw9 |

22% reduction in vascular eventsw8 | Possible improvement in walking distancew10 |

| Treatment of diabetes mellitus | Screen for type 2 diabetesw11*,w12* | Intensive control with insulin or sulphonylurea leads to RR=0.94 (0.8 to 1.1) for total mortalityw11 Intensive control with metformin in overweight patients leads to RR=0.64 (0.45 to 0.91) for total mortalityw12 |

RR=0.51 (0.01 to 19.64) for risk of lower limb amputationw11* |

| Blood pressure | Reduce blood pressure to <140/85 mm Hgw13* | RR=0.87 (0.81 to 0.94) for total mortalityw14* | Not known |

| ACE inhibitors | Should be considered in all patients, even if normotensivew15*,w16* | RR=0.73 (0.61 to 0.86) for composite endpoint of myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death (in diabetes RR=0.75 (0.64 to 0.88))w15*,w16* | Not known |

| Exercise | Patients with lower limb disease should be given written advice about exercise and enrolled in a supervised programme if availablew17,w18 | 24% reduction (primary and secondary prevention) in cardiovascular mortalityw19* | Improvement in walking distance of 150%w20 |

| Cilostazol | Useful addition in patients who have unacceptable symptoms despite adherence to best medical therapyw21-w23 | Unknown | Significant increase in walking distancew21-w23 |

ACE=angiotensin converting enzyme; HDL=high density lipoprotein cholesterol; RR=relative risk (95% confidence interval).

Evidence from patients without peripheral arterial disease.

Smoking cessation

Complete and permanent cessation of smoking is by far the single most important factor determining the outcome of patients with intermittent claudication.w5 Unfortunately, rates of cessation after simple oral or written advice from a doctor are as low as 13% at two years.6 Randomised controlled trials have shown that nicotine replacement treatment approximately doubles the cessation rate in unselected smokers.w2 Bupropion has a similar benefit when used with intensive support.w3 Both treatments are now available on prescription, and every patient with claudication should be offered nicotine replacement treatment in the first instance. Not all nicotine replacement preparations (patches, gum, sprays) are the same, and if one preparation is unsuccessful then other preparations, or combinations with different delivery profiles, should be tried. The Cochrane group found smoking classes but not alternative therapies (hypnotherapy, acupuncture, or “aversive smoking”) to be beneficial.7–9,w4

Antiplatelet agents

The Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration showed that prescription of an antiplatelet agent, usually aspirin, reduced vascular death in patients with any manifestation of atherosclerotic disease by about 25% and that antiplatelet agents were equally effective in patients who present with coronary artery disease and with peripheral arterial disease.10,w8 Some indirect evidence shows that some antiplatelet agents may also improve walking distance in people with claudication.w10 Clopidogrel is at least as effective as, and possibly more effective than, aspirin in patients with peripheral arterial disease and has a better side effect profile.w9 However, it is much more expensive and is generally reserved for the sizeable minority of patients with peripheral arterial disease who cannot take aspirin or who continue to have events on aspirin. No data exist to support the routine use of combination treatment (aspirin and clopidogrel) in patients with peripheral arterial disease, but trials are under way.

Management of diabetes mellitus

Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, or its exclusion, is important in patients with peripheral arterial disease (box), but this is not straightforward.11 A threshold of fasting glucose >7.0 mmol/l, as recommended by Diabetes UK, should be supported by symptoms of diabetes and may miss a large number of asymptomatic patients (20-30%). The oral glucose tolerance test is the “gold standard” but is logistically difficult. In practice, random blood glucose may be the easiest measure to obtain; a random blood glucose >11.1 mmol/l (plasma glucose performed in an accredited laboratory not finger prick, capillary glucose) is diagnostic of type 2 diabetes, and a random blood glucose of 7.0-11.1 mmol/l should followed with an oral glucose tolerance test.

Rationale for screening for diabetes mellitus in intermittent claudication

Up to 20% of patients with intermittent claudication have diabetes; in up to 50% of cases this may be undiagnosed at the time of presentation

The United Kingdom prospective diabetes study has shown that intensive glycaemic control reduces the microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes and that the use of metformin reduces macrovascular complications in overweight people with diabetesw8,w9

Most studies show that diabetes is a powerful risk factor for progression to critical limb ischaemia16

Patients with diabetes should have tighter limits placed on blood pressure and, possibly, lipid concentrations17,18

Diabetic patients are more likely to have spuriously high ankle pressures19

Diabetic patients respond less well to surgical intervention but gain a greater benefit from medical treatments for cardiovascular disease than do non-diabetic patients20

Many diabetic patients have neuropathy, which, in combination with arterial insufficiency, puts them at increased risk of neuroischaemic tissue loss

Hypertension

The benefit of treating hypertension in terms of reducing stroke and coronary events is well accepted; data indicate a target of less than 140/85 mm Hg for non-diabetic patients and 140/80 mm Hg for patients with type 2 diabetes.w13 However, in the short term a reduction in blood pressure may worsen intermittent claudication. This is true of whatever drug treatment has been used, and no evidence exists that β blockers are particularly culpable.12 The heart outcomes prevention evaluation study has shown that ramipril, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, reduces cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease by around 25%.w15,w16 Patients did not have to be hypertensive to be included in the study, and the observed risk reduction could not be accounted for by the relatively modest reduction in blood pressure. The implication of the heart outcomes prevention evaluation study is that most patients with peripheral arterial disease would benefit from an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, provided that treatment is not associated with a deterioration of renal function due to occult renal artery stenosis.

Exercise

A recent Cochrane review has shown that exercise treatment can produce a significant and clinically meaningful increase in walking distance (150%) in most people with claudication who adhere to it.w20 Although the exact mechanisms by which exercise leads to clinical improvement have not been precisely defined, several factors that help to maximise benefit from exercise treatment have been identified (table B on bmj.com). The clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of best medical treatment, best medical treatment plus supervised exercise, and best medical treatment plus angioplasty are currently being evaluated in the exercise versus angioplasty in claudication trial funded by Health Technology Assessment.

Reduction in cholesterol

The heart protection study has shown that lowering total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol by 25% with a statin reduces cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in patients with peripheral arterial disease by around a quarter, irrespective of age, sex, or baseline cholesterol concentration.w6 The implication is that every patient with peripheral arterial disease should be treated with a statin. The lipid profile should be measured before and six weeks after starting treatment, to ensure that a 25% reduction in cholesterol is being achieved and to identify those few patients with very high cholesterol concentrations or hypertriglyceridaemia who may benefit from referral to a specialist lipid clinic.

Adjuvant treatment

Cilostazol has been shown to significantly increase (35-109%) walking distance in people with claudication in several large double blind placebo controlled randomised trials.w21-w23 The precise role of cilostazol remains to be defined, but a trial of the drug is probably indicated in patients who have unacceptable symptoms despite three to six months of adherence to best medical treatment. No convincing evidence supports treatment with other drugs or vitamins,13 but trials evaluating the effect of folate and vitamin B-12 on hyperhomocysteinaemia, a putative vascular risk factor, are near completion.

When should a patient be referred to a vascular surgeon?

Local circumstances vary considerably, but referral is appropriate if

The primary care team is not confident of making the diagnosis, lacks the resources necessary to institute and monitor best medical treatment, or is concerned that the symptoms may have an unusual cause

The patient has unacceptable symptoms despite a reasonable trial of, and adherence to, best medical treatment

The patient has weak or absent femoral pulse(s) (see below).

Patient with critical limb ischaemia (rest pain, gangrene, or ulceration) should be referred urgently (preferably by telephone) to the next vascular surgical clinic. The patient should also be referred urgently if an abdominal aortic aneurysm is suspected on abdominal examination or if the history suggests a carotid territory transient ischaemia attack or amaurosis fugax.

Vascular and endovascular surgery

No convincing evidence supports the use of percutaneous balloon angioplasty or stenting in patients with intermittent claudication.14 Two randomised controlled trials have shown that although successful percutaneous balloon angioplasty may lead to a short term (six months) improvement in walking distance, in the longer term (two years) best medical treatment is better than percutaneous balloon angioplasty in terms of walking distance and quality of life measures.4 The exercise versus angioplasty in claudication trial is further evaluating the role of percutaneous balloon angioplasty.5 In the United Kingdom bypass surgery is performed only infrequently for intermittent claudication because

The risks of surgery are generally believed to outweigh the benefits in most patients who improve on best medical treatment

Even though symptoms are frequently unilateral, most people with claudication have bilateral disease; revascularising one leg often simply serves to unmask hitherto asymptomatic contralateral disease.

In general, the threshold for percutaneous balloon angioplasty, stenting, and surgery is lower in patients who have predominantly aortoiliac (suprainguinal) disease because

In terms of walking distance, such patients seem to benefit less from best medical treatment, although they gain just as much in terms of protecting life and limb; this may be because the body is less able to collateralise around an aortoiliac block

Percutaneous balloon angioplasty and stenting in the aorta or iliac arteries is more durable than that below the inguinal ligament, presumably because larger calibre, high flow arteries are involved

Aortoiliac reconstruction deals with both legs at the same time.

This greater readiness to intervene in patients with absent or diminished femoral pulses in no way undermines the key role of best medical treatment. Furthermore, aortoiliac reconstruction in a patient who also has severe infrainguinal disease is unlikely to lead to a clinically significant reduction in symptoms. See bmj.com for more details on endovascular techniques.4,5,14,21,22

Ongoing research

Several recent landmark trials have confirmed the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of best medical treatment for peripheral arterial disease, and further trials are under way. The exercise versus angioplasty in claudication trial will help to define the role of adjuvant treatments such as percutaneous balloon angioplasty and supervised exercise (see bmj.com). The main challenge facing people caring for patients with peripheral arterial disease is applying what we know already. Primary care teams are best placed to deliver this highly effective and evidence based care, possibly through the establishment of community based, nurse led, protocol driven vascular clinics to which general practitioners can refer any “vascular” patient who needs best medical treatment. Interested general practitioners or secondary care specialists in vascular medicine or surgery could oversee such clinics, which would have clear and widely agreed policies for further investigations and referral to secondary care. Such clinics would need additional funding in the short term but would be likely to be cost neutral, or even beneficial, in the medium and long term through the prevention of expensive vascular events such as stroke and amputation.

Additional educational resources

ABC of arterial and venous disease. BMJ 2000;320. Review articles on

Non-invasive methods of arterial and venous assessment: p 698-701

Acute limb ischaemia: p 764-7

Chronic limb ischaemia: p 854-7

Secondary prevention of arterial disease: p 1262-5

Cochrane review of exercise therapy in peripheral arterial disease—Leng GC, Fowler B, Ernst E. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000990

Consensus document on peripheral arterial disease—TASC Working Group. Management of peripheral arterial disease: transatlantic intersociety consensus (TASC). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2000;19(suppl A):S1-244. (250 page evidenced based document produced by international expert panel, covering all aspects of peripheral arterial disease (also available at www.tasc-pad.org))

Information for patients

The Vascular Surgical Society of Great Britain and Ireland produces patient information sheets on intermittent claudication, arteriograms, percutaneous balloon angioplasty, and amputations—available from www.vssgbi.org

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Extra references, tables, figure, and information are on bmj.com

References

- 1.Fowkes FGR, Housley E, Cawood EHH, MacIntyre CAA, Ruckley CV, Prescott RJ. Edinburgh artery study: prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:384–391. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leng GC, Fowkes FGR. The Edinburgh claudication questionnaire: an improved version of the WHO/Rose questionnaire for use in epidemiological surveys. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1101–1109. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90150-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leng GC, Lee AJ, Fowkes FGR, Whiteman M, Dunbar J, Housley E, et al. Incidence, natural history and cardiovascular events in symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:1172–1181. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whyman MR, Fowkes FG, Kerracher EM, Gillespie IN, Lee AJ, Housley E, et al. Is intermittent claudication improved by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty? A randomised controlled trial. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:551–557. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkins JM, Collin J, Creasy TS, Fletcher EW, Morris PJ. Exercise training versus angioplasty for stable claudication: long and medium term results of a prospective randomised trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(96)80171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch AT, Treat-Jacobson D, Lando HA, Hatsukami DK. The role of tobacco cessation, antiplatelet and lipid-lowering therapies in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease. Vasc Med. 1997;2:243–251. doi: 10.1177/1358863X9700200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abbot NC, Stead L, White A, Barnes J, Ernst E. Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD001008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. Hajek P, Stead LF. Aversive smoking for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000546. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. White AR, Rampes H, Ernst E. Acupuncture for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Antiplatelet Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy—I: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ. 1994;308:81–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diabetes UK. Diabetes UK position statement 2002. Early identification of people with type 2 diabetes. www.diabetes.org.uk (accessed Nov 2002).

- 12.Heintzen MP, Strauer BE. Peripheral vascular effects of beta-blockers. Eur Heart J. 1994;15(suppl C):2–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/15.suppl_c.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kleijnen J, Mackerras D. Vitamin E for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.TASC Working Group. Management of peripheral arterial disease: transatlantic intersociety consensus (TASC) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;19(suppl A):S1–244. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dormandy J, Heeck L, Vig S. Lower-extremity atherosclerosis as a reflection of a systemic process: implications for concomitant coronary and carotid disease. Semin Vasc Surg. 1999;12:118–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dormandy J, Heeck L, Vig S. The natural history of claudication: risk to life and limb. Semin Vasc Surg. 1999;12:123–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pyöräla K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Faergeman O, Olsson AG, Thorgeirsson G. Cholesterol lowering with simvastatin improves prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary heart disease. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:614–620. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38 [correction appears in BMJ 1999;318:29] BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orchard TJ, Strandness DE. Assessment of peripheral vascular disease in diabetes: report and recommendations of an international workshop sponsored by the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1993;88:819–828. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutteridge W, Torrie EPH, Galland RB. Cumulative risk of bypass, amputation or death following percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997;14:134–139. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(97)80210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.London NJ, Srinivasan R, Naylor AR, Hartshorne T, Ratliff DA, Bell PR, et al. Subintimal angioplasty of femoropopliteal artery occlusions: the long-term results. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1994;8:148–155. doi: 10.1016/s0950-821x(05)80450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy RJ, Neary W, Rowbottom C, Tottle A, Ashley A. Short term results of femoropopliteal sub-intimal angioplasty. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1361–1365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.