Abstract

This research aims to determine the relationship between flexible working arrangements (FWAs) and employee performance (EP). The research was conducted by reviewing studies in Web of Science (WoS), EBSCO and Google Scholar databases between 2010 and 2024. The research was screened in the databases in line with the inclusion criteria, which were determined as studies written in English, where data were collected by survey technique, data were analyzed by correlation, and those that met the criteria were included in the research. As a result of the preliminary screening, second screening, and screening in line with the inclusion criteria, the remaining 21 studies constituted the data set of this study. The correlation between FWAs and EP was [r(20) = 0.596, p < 0.05]. This value can be interpreted a significant and high-level relationship between them. According to the random model, Fisher’s Z and 95% CI (LL = 0.52 and UL = 0.84), Z = 8.45, measured an effect size of 0.35 p = 0.000. This value shows a moderate effect size according to Cohen’s d. FWAs have a positive effect on EP, productivity, job satisfaction, job stress, work-family harmony, and organizational commitment. It is recommended that organizations, managers, organizational psychology, and human resources professionals (HRP) should include FWAs in job analysis, job design, and planning.

Keywords: flexible work arrangements, part-time, telecommuting, compressed work weeks, employee performance

1. Introduction

Flexible working has become increasingly common in many countries in recent years, with many employers offering some form of flexible working to their employees and a significant number of employees taking advantage of these opportunities (De Menezes and Kelliher, 2017). Due to its dynamic nature, working life has been in a state of constant change for the last 50 years. Since the mid-1970s, part-time work has become increasingly common. Part-time work now represents a common form of work arrangements. According to Eurostat, in 2010, around 67% of workers in Europe worked part-time (Devicienti et al., 2018). Especially in the last 25 years, with the widespread use of the internet, computers, and smartphones in social life, working life has changed its form, while it has taken a different dimension with the Coronavirus (Covid-19), which affected the whole world in 2019–2022. The Covid-19 pandemic has led to the reorganization of workplace environment and redesign of work processes in many organizations. In the early times of the pandemic, the number of employees working in enclosed work environments and the operational capacity of organizations were reduced. For full operational use, some organizations waited for the effects of the pandemic to subside, while others took a new approach by taking advantage of technological innovations and passed on to flexible working arrangements (FWA) (Chukwudi et al., 2022). Internet and computer technology initially globalized a significant part of work without time and place limitations. Especially during Covid-19, people worked at workplaces for shorter periods of time (except health workers), while those in some jobs conducted their work from home via the internet. Working from home has become more common during COVID-19 due to public health measures (Zhang et al., 2022). Teleworking, which is different from telecommuting, allows workers to maintain online communication with colleagues and customers even while traveling without the obligation to be tied to a place. Teleworking is defined as a work flexibility arrangement in which an employee carries out the duties and responsibilities related to his/her job at a workplace other than his/her workplace (Kawakubo and Arata, 2022). According to Prasad and Mishra (2021), flexibility in work life is more possible today with the development of technology. Studies have shown that flexible working is positively associated with increased productivity, lower absenteeism, and higher job satisfaction (Scandura and Lankau, 1997; Baltes et al., 1999; Konrad and Mangel, 2000; Kelliher and Anderson, 2008). Since the 2000s, the working arrangement has had to change due to technological developments and epidemics that threaten public health (such as COVID-19, SARS and Bird flu). The most important of these changes is flexible working arrangements. At this point, it is important to determine the effect of flexible working arrangements on employee performance.

1.1. Flexible work arrangements

Flexibility in working life gives employees the option to fulfill their work and non-work demands. The term flexible working includes flexibility regarding hours and location and is broad in scope. Shift work, part-time work, telecommuting, compressed work, sabbatical, flexi-time, job sharing, seasonal work, annual working hours, vacation time and much more are related to flexible working (Prasad and Mishra, 2021). Flexi-time is an arrangement that allows employees to choose when to start or finish work, other than regular time, as long as they complete a certain number of hours (Chukwudi et al., 2022). Compressed work weeks are defined as working a full-time schedule while shifting some of those hours to longer days to get more time off on other days. For example, instead of working 8 h a day 5 days a week, working 10 h a day 4 days a week (Galinsky et al., 2011). The term sabbatical (extended leave or personal retreat) has numerous options in today’s ed. context. It can mean taking a break for any time, from a month to several years (Carr and Tang, 2005). Employees have the freedom to choose where they work, which offers significant location flexibility. This means that job duties can be performed from a variety of work locations appropriate to the nature of the job. For example, at home, at the client’s location, on the train, in a café, etc. This type of flexible working arrangement is defined as teleworking (Wessels, 2017). Job sharing is an agreement that allows two or more individuals to work in a full-time job and share responsibilities between themselves (Ifeoma, 2019). According to Aziz-Ur-Rehman and Siddiqui (2019), flexible working helps people to achieve work-life balance. People are committed to both work and personal life and attach importance to both. This helps them to fulfill their work responsibilities as well as their personal life responsibilities while increasing satisfaction in both their personal and professional life. According to Boyer (1988), flexibility and productivity go hand in hand in working life.

1.2. Employee performance

According to Güngör (2011), employee performance is what an employee does or does not do. Employee performance includes output quantity, output quality, timeliness of output, presence at work, and cooperation. What organizations expect from employees is to do the work fully and accurately. Task performance and contextual performance are determinants of employee performance. Task performance is the employee’s fulfillment of the responsibilities in the job description. Contextual performance refers to behaviors that are not directly related to one’s job, but voluntarily support the success of others for the effectiveness of the organization (Sarpkaya and Bayraktar, 2023). According to Prasad and Mishra (2021), employee performance is a key factor for an organization to survive in competition. Individual performance plays an important role in a higher level of organizational performance. An individual’s high performance in performing their tasks results in feelings of satisfaction, self-efficacy, and mastery. Employee performance refers to the achievement of agreed work outcomes on the employee’s work behaviors, which can be achieved through productivity, work quality, or other means (Ludidi, 2020). Although there have been many studies on the impact of flexible working arrangements on employees’ work behaviors and performance, this research was conducted because there were not enough meta-analysis studies that addressed the relationship between flexible working arrangements and, the Covid-19 process and, technological changes. This research aims to determine the relationship between flexible working arrangements and employee performance between 2010 and 2024. In line with this purpose, the research questions are given below:

What are the concepts in the studies on flexible working arrangements and employee performance?

What is the relationship and the effect size between flexible working arrangements and employee performance in the studies included in this research?

Due to technological developments in 2010–2024 and COVID-19 changing working arrangements, only studies during this period were included in the scope of this research.

2. Method

This research was conducted by systematic review method and its procedure. This research aims to construct a mini review on flexible work engagements and employee performance. The research is based on published studies examining the relationship between flexible working arrangements and employee performance between 2010 and 2024 years and follows the PRISMA method of systematic review (Moher et al., 2009).

2.1. Data collection process

The research data were searched in WoS, EBSCO and Google Scholar databases by entering “and,” “or” between the keywords “Flexible working arrangements,” “Employee performance,” “Job performance,” “Employee productivity,” “Flexible working,” “Worker performance,” “Flexi time.” Research articles and theses written in English, in which correlation analysis was applied among the studies that collected data with survey method between 2010–2024 were used as inclusion criteria. Master’s and doctoral theses require the application of scientific research methods and techniques. In addition, thesis must be approved by a jury of at least three academics in order to be accepted. For this reason, thesis are accepted as an academic and scientific work. All studies other than research articles were excluded. The titles, abstracts, and method sections of the 884 studies identified in the initial screening were read one by one by the researchers, and 101 studies that could be included in the scope of the study were identified. Of these studies, 21 studies that were not suitable for the research focus were eliminated, the full texts of the remaining 80 studies were read in detail by two researchers separately to determine whether they fully fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and the remaining 21 studies (18 articles, 2 master thesis and 1 doctoral thesis) were determined to meet the research criteria by consensus between the two authors.

2.2. Data analysis

CMA 3.0 program was used to calculate the effect size between variables. The authors examined the 21 studies included in the study in detail one by one. Differences of opinion between the researchers during the data analysis were resolved by making joint decisions. Accordingly, the authors, study type, location, sample size, participants’ profession, language, data collection method, study variables, and number of citations were determined. Accordingly, the total sample size of the studies conducted in 9 different countries is 4,274. Other characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies.

| Id | Authors | Study type | Country | N | Participants | Language | Correlation coefficient | Scales | Cited by |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agbanu et al. (2023) | Article | Nigeria | 162 | Sales Representatives | English | 0.798* | FWAS, EProS. | 3 |

| 2 | AhmedAlqasa and Alsulami (2022) | Article | Saudi Arabia | 107 | Education Sector Employees | English | 0.460** | FWOQ, EPS | 1 |

| 3 | Altındağ and Siller (2014) | Article | Türkiye | 200 | Various Sector Employee | English | 0.207* | FWMS, EPS | 69 |

| 4 | Alwi (2021) | Article | Pakistan | Unspecified | Multinational Company Employees | English | 0.412** | FWQ, EPS | 0 |

| 5 | Babu et al. (2011) | Article | India | 300 | IT Employees | English | 0.589** | FTS, EPS | 0 |

| 6 | Bett et al. (2022) | Article | Kenya | 137 | Agricultural Cooperatives Employees | English | 0.801** | FWAS, EPS | 0 |

| 7 | Dikirr and Omuya (2023) | Article | Kenya | 260 | Academic Staff | English | 0.467** | FTQ, EPQ | 1 |

| 8 | Govender (2017) | PhD. Thesis | South Africa | 92 | Unspecified | English | 0.585** | FWAS, EP | 5 |

| 9 | Mbae et al. (2019) | Article | Kenya | 219 | Electricity Company Employees | English | 0.753** | JFS, EPS | 1 |

| 10 | Muga and Senelwa (2022) | Article | Kenya | 155 | Public Health Sector | English | 0.088 | FWPS, EPS | 1 |

| 11 | Mwebi and Kadaga (2015) | Article | Kenya | 291 | Bank Employees | English | 0.344** | FWAQ, EPQ | 37 |

| 12 | Nayanathara and Karanurathne (2021) | Article | Sri Lanka | 169 | IT Employees | English | 0.521** | FWS, EJP | 2 |

| 13 | Nnko (2022) | Ph.D. Thesis | Kenya | 404 | Nurse | English | 0.469** | WSS, NPS | 1 |

| 14 | Nurudeen et al. (2024) | Article | Nigeria | 248 | Private Hospital Employee | English | 0.711** | FWAQ, EPQ | 0 |

| 15 | Obisi (2017) | Article | Nigeria | 160 | School Employee | English | 0.720** | FWSS, EPS | 11 |

| 16 | Odunayo and Kelvin (2020) | Article | Nigeria | 285 | Logistics Companies Employee | English | 0.921** | FWOQ, EPQ | 11 |

| 17 | Osisioma et al. (2016) | Article | Nigeria | 33 | Health Workers | English | 0.411* | FWHS, EPS | 11 |

| 18 | Ramlan et al. (2023) | Article | Malaysia | 60 | Bank Employees | English | 0.828** | FWQ, JPQ | 0 |

| 19 | Sekhar and Patwardhan (2023) | Article | India | 214 | Service Firm Employees | English | 0.299** | TFWAS, JPS | 19 |

| 20 | Tamunomiebi (2018) | Article | Nigeria | 327 | Academic Staff | English | 0.675** | FTWPQ, EPQ | 6 |

| 21 | Yau (2023) | Master Thesis | Malaysia | 201 | Private Sector | English | 0.529** | FWAS, EPS | 0 |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.FWAS, Flexible Work Arrangement; EProS, Employee Productivity; FWOQ, Flexible Work Options questionnaire; EPS, Employee Performance; FWMS, Flexible Working Method Scale; FWQ, Flexible Working Questionnaire; FTS, Flexi Time Scale; FWAS, Flexible Work Arrangement Scale; FTQ, Flexi Time Questionnaire; EPQ, Employee Performance Questionnaire; JFS, Job Flexibility Scale; FWPS, Flexibility Work Practice Scale; FWAQ, Flexitime Work Arrangement Questionnaire; FWS, Flex Work Scale; EJP, Employee Job Performance; WSS, Work Scheduling Scale; NPS, Nurses Performance Scale; FWAQ, Flexible Work Arrangements Questionnaires; FWSS, Flexible Work Schedules Scale; FWHS, Flexible Working Hours Scale; JPQ, Job Performance Questionnaire; TFWAS, The Flexible Working Arrangement Scale; JPS, Job Performance Scale; FTWPQ, Flexi Time Work Practice Questionnaire.

3. Findings

The 21 studies within the scope of the research were conducted in 9 different countries. When these countries are analyzed, 6 studies were conducted in Kenya and 6 studies were conducted in Nigeria, 13 of which are located in the African continent, while 1 study was conducted in South Africa. In Asia, 7 studies were conducted, 1 in Saudi Arabia, 2 in India, 1 in Pakistan, 1 in Sri Lanka, and 2 in Malaysia. From the European continent, there is only 1 study conducted in Turkey. The total sample size of these studies is 4,274. The studies included participants from a variety of different business areas (such as health, education, banking). In the studies, Likert-type scales are used to measure flexible working arrangements and employee performance. Employee performance is generally measured with the employee performance scale. Measurement tools such as flexible working options scale, flexi time questionnaires, flexibility work practice scale, flexible work schedules scale are used to measure flexible working arrangements. When the studies are analyzed according to their citations, it is seen that the 3rd-ranked study conducted in Turkey is the most cited. The high citation rate of this study may be due to the fact that it was published earlier than other studies. This study was followed by the study conducted in Kenya, which ranked 11th and received 37 citations. Apart from these, the study conducted in India in 2011, which ranked 6th, did not receive any citations. Likewise, studies ranked 4th, 5th, 6th, 18th, and 21th did not receive any citations. It should be noted that these studies are more recent than the 2011 study. According to the heterogeneity and effect size calculations, the random effect model is used since the heterogeneity value is p = 0.000 and p < 0.05. Also Q = 544.469, df = 20 is found from FWAs-EP values. Chi-square for FWAs-EP is 31.410 at 0.05 level of significance at 20 degrees of freedom. The I2 value is calculated as 96, 327%, which is greater than 75% in the I2 indicator, thus indicating high heterogeneity among the research variables (Borenstein et al., 2021). Random model is used since the data showed heterogeneity. According to the random model, the correlation between FWAs and EP is [r(20) = 0.596, p < 0.05]. The correlation value corresponding to Fisher’s Z indicates a statistically high, significant and positive relationship. The effect size [Fisher’s Z and 95% CI (LL = 0.52 and UL = 0.84), Z = 8.45] is measured 0.35 and p = 0.000. According to Cohen’s d, this value can interpret a moderate effect size (Cohen, 1988).

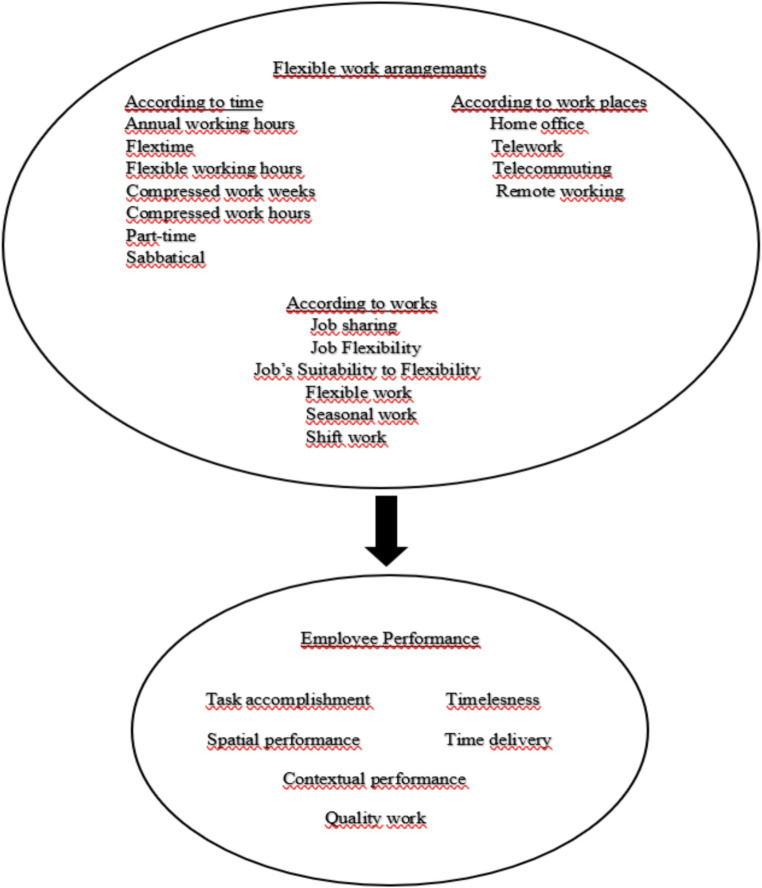

Flexible working arrangements can be made in three contexts: time, works and workplaces. Employee performance is about getting things done successfully, on time and with good work quality. Figure 1 below shows the impact of flexible working arrangements on employee performance.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

According to the results of meta-analysis applied to research data obtained after a systematic review of studies; the mean correlation value of flexible working arrangements and employee performance is calculated as [r(20) = 0.596]. Accordingly, it can be said that there is a highly significant and positive relationship between flexible working arrangements and employee performance. The calculated effect size is 0.355. This value indicates a moderate effect size according to Cohen’s d. Therefore, in line with these results, it can be said that flexible working arrangements have a significant and moderate effect on employee performance. This result is consistent with many studies (Giovanis, 2018; Ifeoma, 2019; Ramakrishnan and Arokiasamy, 2019; Idowu, 2020; Ludidi, 2020; Msuya and Kumar, 2022; Mustakim, 2022; Yuliati et al., 2023). Organizations can offer flexible working arrangements to retain productive employees. This has been shown to increase employee’ performance, satisfaction, loyalty, and productivity, and reduce absenteeism and recruitment costs (Giovanis, 2015; Abid and Barech, 2017; De Menezes and Kelliher, 2017; Bukhari et al., 2018). Flexible working arrangements are beneficial for employees in terms of reducing work stress, increasing job satisfaction and life satisfaction, providing mental and physical balance, and for organizations in terms of increasing work efficiency and effectiveness (Costa et al., 2006; Masuda et al., 2012; Solanki, 2013; Kröll and Nüesch, 2017). Flexible working arrangements help employees to manage their workload, personal life, and responsibilities. They also reduce conflict by helping employees better manage the boundaries between work and home life (Jivan, 2017; Aziz-Ur-Rehman and Siddiqui, 2019; Eshak et al., 2021; Chukwudi et al., 2022). Research generally reveal the positive effects of flexible working arrangements on employee behavior and performance. More specifically, employees with flexible working arrangements can control work stress caused by tension, fatigue and excessive workload. Burnout and work accidents caused by intense and excessive work tempo can be prevented. Conflicts between employees and their colleagues or supervisors can be reduced with flexible working arrangements. Since employees can arrange their work hours according to their needs and the demands of their families, they may have positive feelings towards their work and the organization, which may reflect positively on their job performance. Employees who are allowed to work flexibly generally show increased organizational commitment, attendance, and performance. Commitment to the team was seen as a prerequisite for flexible working to be effective as well as for strengthening organizational commitment. Organizations with flexible working arrangements can provide more versatility to their employees and thus create a more compatible work pattern than organizations with fixed work patterns and working hours (Altındağ and Siller, 2014; Choudhary, 2016; Mungania et al., 2016; Ifeoma, 2019; Anya et al., 2021).

The results of this research can be used especially by managers, organizational psychology and HRP for job analysis, job design, job planning, job motivation, and performance appraisal. Flexible working arrangements can protect employees against stress, especially from the work itself, customer intensity, extreme hot, cold or humid working conditions, and family-work harmony. The research is limited by the number of studies included in the systematic review. Further studies in different cultures in Europe, which are not included in this research in sufficient numbers, and the Americas and Australia, which are not included in this research, may reveal more comprehensive results. To better understand the psychological, social, cultural, and economical effects of flexible working, it is recommended to research employees and organizations in different sectors in different countries.

Author contributions

AÇ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ŞD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abid S., Barech D. K. (2017). The impact of flexible working hours on the employees’ performance. Int. J. Econ. Commerce Manag. 5, 450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Agbanu I. I., Tsetim J. T., Suleman A. (2023). Flexible work arrangements and productivity of sales representatives of book publishing companies in Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Market. Elements 3, 1–22. doi: 10.59615/ijime.3.1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AhmedAlqasa K. M., Alsulami N. Y. (2022). The impact of flexible work arrangements (FWA) on employees performance in the Saudi education sector. Int. J. Operat. Quantit. Manag. 28, 174–192. doi: 10.46970/2022.28.1.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altındağ E., Siller F. (2014). Effects of flexible working method on employee performance: an empirical study in Turkey. Bus. Econ. J. 5, 1–7. doi: 10.4172/2151-6219.1000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alwi S. A. K. (2021). Impact of telecommuting, part time, and flexi time on the productivity of multinational company employees. Propel J. Appl. Manag. 1, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Anya P. J., Adeniji A. A., Salau O. P., Balogun O. M., Aribisala S. O., Ikeagbo J. O. (2021). Examining employee engagement within the context of flexible work arrangement in Asian-owned company in Lagos state. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz-Ur-Rehman M., Siddiqui D. A. (2019). Relationship between flexible working arrangements and job satisfaction mediated by work-life balance: evidence from public sector universities employees of Pakistan. Int. J. Hum. Resource Stud. 10, 104–127. doi: 10.5296/ijhrs.v10i1.15875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babu D. S. S., Prasad D. U. D., Sheik F., Raj K. B. (2011). Impact of flexi-time (a work-life balance practice) on employee performance in Indian IT sector. Int. J. Res. Comput. Appl. Manag. 1, 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes B. B., Briggs T. E., Huff J. W., Wright J. A., Neuman G. A. (1999). Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: a meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 496–513. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.84.4.496 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bett F., Sang H., Chepkwony P. (2022). Flexible work arrangement and employee performance: an evidence of work-life balance practices. East African J. Business Econ. 5, 80–89. doi: 10.37284/eajbe.5.1.557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P. T., Rothstein H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., London. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer R. (1988). The search for labour flexibility. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari S. S., Gupta M., Taggar R. (2018). An empirical study on employees perception of existing flexible work practices and its impact on their performance. Amity Global HRM Rev. 8, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Carr A. E., Tang T. L. P. (2005). Sabbaticals and employee motivation: benefits, concerns, and implications. J. Educ. Bus. 80, 160–164. doi: 10.3200/JOEB.80.3.160-164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary S. (2016). A theoretical framework on flexible work schedules. Int. J. Acad. Res. Develop. 1, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwudi C. G., Ukegbu O. P., Anthony N. O. (2022). Flexible work arrangement and employees’ performance during COVID-19 era in selected micro-finance banks in Enugu state. Asian J. Econ. Finance Manag. 4, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Edn. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Costa G., Sartori S., Åkerstedt T. (2006). Influence of flexibility and variability of working hours on health and well-being. Chronobiol. Int. 23, 1125–1137. doi: 10.1080/07420520601087491, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Menezes L. M., Kelliher C. (2017). Flexible working, individual performance, and employee attitudes: comparing formal and informal arrangements. Hum. Resour. Manag. 56, 1051–1070. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devicienti F., Grinza E., Vannoni D. (2018). The impact of part-time work on firm productivity: evidence from Italy. Ind. Corp. Chang. 27, 321–347. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtx037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dikirr S. N., Omuya J. (2023). Influence of flexible work practices on employee performance in institutions of higher learning in Kenya: a case of selected universities in Nyeri County. Afr. J. Educ. Sci. Technol. 7, 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Eshak M., Hassan M. W. M., Ghanem A. N. (2021). Flexible work arrangements and their impact on the employee performance of Egyptian private university employees:(a case study on the Arab academy for science, technology, and maritime transport). Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 4, 2729–2741. doi: 10.47191/ijsshr/v4-i10-13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galinsky E., Sakai K., Wigton T. (2011). Workplace flexibility: from research to action. Fut. Child 21, 141–161. doi: 10.1353/foc.2011.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanis E. (2015). Flexible employment arrangements and workplace performance, MPRA paper. Available at: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/68670/

- Giovanis E. (2018). The relationship between flexible employment arrangements and workplace performance in Great Britain. Int. J. Manpow. 39, 51–70. doi: 10.1108/IJM-04-2016-0083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govender L. (2017). Flexible work arrangements, job satisfaction and performance within Eskom shared services, Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Kuwazulu-Natal, Durban.

- Güngör P. (2011). The relationship between reward management system and employee performance with the mediating role of motivation: a quantitative study on global banks. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 24, 1510–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Idowu S. A. (2020). Role of flexible working hours’ arrangement on employee job performance and retention in manufacturing industries in Agbara Nigeria. Econ. Insights Trends Challenges 9, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ifeoma A. R. (2019). Flexible work arrangement and employee performance of selected commercial banks in Anambra state Nigeria. Int. J. Acad. Inform. Syst. Res. 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jivan H. (2017). The exploration into the impact of flexible working hours on employee performance, motivation and personal life for women at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Durban.

- Kawakubo S., Arata S. (2022). Study on residential environment and workers’ personality traits on productivity while working from home. Build. Environ. 212:108787. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.108787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher C., Anderson D. (2008). For better or for worse? An analysis of how flexible working practices influence employees’ perceptions of job quality. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 19, 419–431. doi: 10.1080/09585190801895502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad A. M., Mangel R. (2000). Research notes and commentaries the impact of work-life programs on firm productivity. Strateg. Manag. J. 21, 1225–1237. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kröll C., Nüesch S. (2017). The effects of flexible work practices on employee attitudes: evidence from a large-scale panel study in Germany. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 30, 1505–1525. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2017.1289548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ludidi F. (2020). Flexible working arrangements and employee performance: Manager and employee perspectives, Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria, Hatfield.

- Masuda A. D., Poelmans S. A., Allen T. D., Spector P. E., Lapierre L. M., Cooper C. L., et al. (2012). Flexible work arrangements availability and their relationship with work-to-family conflict, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: a comparison of three country clusters. Appl. Psychol. 61, 1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2011.00453.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mbae C., Ogolla D., Mbebe J. (2019). Effect of flexible work practices on employee performance in electricity generating companies in Kenya. J. Int. Bus. Innov. Strategic Manag. 3, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msuya M. S., Kumar A. B. (2022). Flexible work arrangements, leave provisions, and employee job performance in banking sector. J. Posit. School Psychol. 6, 5596–5612. [Google Scholar]

- Muga I. O., Senelwa A. (2022). Influence of flexibility work practice and employee performance in public health sector in Kenya. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Inform. Technol. 8, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mungania A. K., Waiganjo E. W., Kihoro J. M. (2016). Influence of flexible work arrangement on organizational performance in the banking industry in Kenya. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 6, 159–172. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v6-i7/2238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustakim J. (2022). Overview of job satisfaction and flexibility on employee performance. Akademik 2, 82–90. doi: 10.37481/jmh.v2i2.472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mwebi M. B., Kadaga M. N. (2015). Effects of flextime work arrangement on employee performance in Nairobi CBD commercial banks. Int. J. Novel Res. Market. Manag. Econ. 2, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Nayanathara S. W. A. W. M. D., Karunarathne R. A. I. C. (2021). Impact of flex-work on employee performance: study of executive-level employees in IT industry of Sri Lanka. Kelaniya J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 16, 1–19. doi: 10.4038/kjhrm.v16i1.84 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nnko E. E. (2022). Flexible work arrangements on performance of nurses in regional hospitals in Tanzania, Doctoral dissertation, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture And Technology, Tanzania.

- Nurudeen D. S. A., Afolayan D., Michael A., Opele D., Mithias A. (2024). Influence of flexible work arrangements on employees’ performance: the moderating role of perceived organisational support. Int. J. Novel Res. Devel. 9, e631–e641. [Google Scholar]

- Obisi C. (2017). Impact of flexible work arrangement on employees performance in public schools in Lagos state, Nigeria. Ideal J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Odunayo A. O., Kelvin O. F. (2020). Assessing the influence of flexible-work-option as a precursor of work life balance on employee productivity of logistics companies in rivers state Nigeria. Br. J. Manag. Market. Stud. 3, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Osisioma H., Nzewi H., Ifechi I. (2016). Flexible working hours and employee performance in selected hospitals in Awka Metropolis, Anambra state, Nigeria. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad L., Mishra P. (2021). Impact of work life flexibility on work performance of the employees of IT companies. Psychol. Educ. 58, 6084–6089. doi: 10.17762/pae.v58i2.3084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan S., Arokiasamy L. (2019). Flexible working arrangements in Malaysia; a study of employee's performance on white collar employees. Global Bus. Manag. Res. 11, 551–559. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlan N. N., Ahmad N., Shafi M. A. (2023). The relationship between flexible work and job performance among bank employees. Res. Manag. Technol. Bus. 4, 210–224. doi: 10.30880/rmtb.2023.04.02.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarpkaya E., Bayraktar O. (2023). The effect of flexible working on job performance during the Covid 19 pandemic: the mediation role of job characteristics. Uluslararası Ekonomi İşletme Politika Dergisi 7, 367–386. doi: 10.29216/ueip.1295399 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scandura T. A., Lankau M. J. (1997). Relationships of gender, family responsibility and flexible work hours to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 18, 377–391. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhar C., Patwardhan M. (2023). Flexible working arrangement and job performance: the mediating role of supervisor support. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 72, 1221–1238. doi: 10.1108/IJPPM-07-2020-0396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solanki K. R. (2013). Flextime association with job satisfaction, work productivity, motivation & employees stress levels. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1, 9–14. doi: 10.11648/j.jhrm.20130101.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamunomiebi M. D. (2018). Flexi-time work practice and employee productivity in tertiary institutions in Rivers state. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels C. (2017). Flexible working practices: How employees can reap the benefits for engagement and performance, Unpublished Doctorate Thesis, Erasmus University, Rotterdam.

- Yau L. S. (2023). A study of the relationship between flexible working arrangements, job environment, job communication, and employee performance, Unpublished Master Thesis, University Utara Malaysia.

- Yuliati L., Smith P. A. W., Prasetyaningtyas S. W. (2023). The influence of flexible working hours, work from home, work stress, and salary on employee performance at PT armada auto Tara during covid-19 pandemic. Quant. Econ. Manag. Stud. 4, 402–413. doi: 10.35877/454RI.qems1619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Sun H., Gelfand A., Sawatzky R., Pearce A., Anis A. H., et al. (2022). Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: the association with work productivity loss among patients and caregivers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 64, e677–e684. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002663, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]