Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transforms human B lymphocytes into immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs). They regularly express six virally encoded nuclear proteins (EBNA1 to EBNA6) and three membrane proteins (LMP1, LMP2A, and LMP2B). In contrast, EBV-carrying Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cells in vivo and derived type I cell lines that maintain the BL phenotype express only EBNA1. During prolonged in vitro culturing, most EBV-carrying BL lines drift toward a more immunoblastic (type II or III) phenotype. Their viral antigen expression is upregulated in parallel. We have used fluorescent in situ hybridization to visualize viral transcripts in type I and III BL lines and LCLs. In type I cells, EBNA1 is encoded by a monocistronic message that originates from the Qp promoter. In type III cells, the EBNA1 transcript is spliced from a giant polycistronic message that originates from one of several alternative Wp or Cp promoters and encodes all six EBNAs. We have obtained a “track” signal with a BamHI W DNA probe that could hybridize with the polycistronic but not with the monocistronic message in two type III BL lines (Namalwa-Cl8 and MUTU III) and three LCLs (LCL IB4-D, LCL-970402, and IARC-171). A BamHI K probe that can hybridize to both the monocistronic and the polycistronic message visualized the same pattern in the type III BLs and the LCLs as the BamHI W probe. A positive signal was obtained with the BamHI K but not the BamHI W probe in the type I BL lines MUTU I and Rael. The RNA track method can thus distinguish between cells that use a type III and those that use a type I program. The former cells hybridize with both the W and the K probes, but the latter cells hybridize with only the K probe. Our findings may open the way for studies of the important but still unanswered question of whether cells with type I latency arise from immunoblasts with a full type III program or are generated by a separate pathway during primary infection.

The spatial organization of nuclear components participating in functions like DNA replication, transcription, RNA processing, and nuclear RNA transport has been increasingly clarified by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques (19, 25, 27).

In order to visualize the target site by in situ hybridization, the target sequence has to be represented in a sufficiently high concentration to provide a good contrast against signal-negative regions. The nuclear abundance and spatial configuration of pre-mRNA are likely to depend on the position of the gene, size of the primary transcript, extent of processing, and level of transcription (2). Specific RNA transcripts could be localized in cell nuclei in earlier studies. Lawrence et al. (17) detected transcripts of integrated EBV genomes as “tracks” in Namalwa cell nuclei. They extended between the interior of the nucleus and the nuclear membrane and were conserved in a nuclear matrix preparation (32). Specific transcripts could be detected in the form of nuclear tracks in other systems as well (4, 10, 25, 34). They were not always in contact with the nuclear envelope, however, raising doubts about their postulated involvement in RNA transport to nuclear pores. It has been speculated that they may represent RNA accumulation sites that emit processed transcripts on their way to the cytoplasm by diffusion (4, 16, 30, 33).

In this study, we have visualized Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transcripts in B-cell-derived human cell lines known to carry integrated and/or episomal EBV genomes. At least three programs of viral gene expression have been demonstrated for latently EBV-infected B cells (14). EBV-transformed immunoblasts (lymphoblastoid cell lines [LCLs] in vitro and immunoblasts in vivo) use the latency III program, expressing nine virally encoded proteins (EBNA1 to EBNA6 and LMP1, LMP2A, and LMP2B). The latency I (EBNA1 only) program is used by Burkitt lymphoma (BL) biopsy cells and BL-derived cell lines as long as they maintain a tumor-representative phenotype (28). In the course of prolonged in vitro culturing, BL cells may drift to a more immunoblastic (type II or III) phenotype, with concomitant switching to a type III program (12). Type I latency is also found in EBV-carrying resting B cells in healthy individuals (3).

Latency II (expression of EBNA1 and the LMPs) is characteristic of EBV-carrying non-B cells, such as Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin’s disease, T-cell lymphomas, and nasopharyngeal and other EBV-carrying carcinomas (5, 9, 23). Freshly infected B cells undergo blast transformation by using the type III program. This is a prerequisite for viral immortalization.

The developmental history of latently infected normal B cells is one of the major remaining puzzles of EBV strategy. One possibility is that they are already generated during primary infection. Conceivably, a small minority of the infected cells may fail to follow the immunoblastic activation program, giving rise to a differently regulated subpopulation of latently infected cells. According to a more likely alternative, a certain function of the activated immunoblasts may change to resting cells by a phenotypic switch that may be identical with, or akin to, the formation of B memory cells. If so, even proliferating EBV-carrying lymphoblastic lines may generate resting B cells and concomitantly downregulate the type III to the type I program.

In order to visualize individual cells that use different viral expression programs, we wished to explore whether the FISH method could be used to distinguish between the Wp- or Cp-initiated, immunoblast-specific polycistronic EBNA1 to -6 (type III) program and the Qp-initiated, monocistronic EBNA1 only (type I) program. We found that the RNA track method permits such a distinction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

(i) Cell culture and nuclear preparation.

Cell lines and their characteristics are listed in Table 1. LCL-970402 was a kind gift of László Székely (Microbiology and Tumor Biology Center [MTC], Karolinska Institute [KI], Stockholm, Sweden). All cell lines were grown in RPMI medium with 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) at 37°C. Interphase nuclei and metaphase chromosomes were analyzed on standard cytogenetic preparations, as previously described (17). Cells were incubated with 0.015 μg of Colcemid per ml for 2 to 3 h, pelleted, and resuspended in 0.075 M KCl at 37°C for 20 min. The cell suspension was fixed by three changes of a 3:1 dilution of fresh methanol-acetic acid and gently dropped onto ethyl alcohol (EtOH)-cleaned slides in a humid environment. Slides were air dried overnight and stored at −80°C with a desiccant.

TABLE 1.

Cell lines

| Cell line (reference) | Type | Derivation | Phenotype | Latency pattern of gene expression | Nuclear antigen(s) expressed | State of the viral genomea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCL-97042 (30a) | LCL | Normal B cell | Immunoblastic | Type III | EBNA1 to -6 | Episomal |

| IARC-171 (18) | LCL | Normal B cell | Immunoblastic | Type III | EBNA1 to -6 | Episomal |

| IB4-D (13) | LCL | Normal B cell | Immunoblastic | Type III | EBNA1 to -6 | Integrated |

| Rael (15) | BL | BL | BL type | Type I | EBNA1 | Episomal |

| MUTU I (7) | BL | BL | BL type | Type I | EBNA1 | Episomal |

| MUTU III (7) | BL | BL | Immunoblastic | Type III | EBNA1 to -6 | Episomal |

| Namalwa-Cl8 (15) | BL | BL | Immunoblastic | Type III | EBNA1 to -6 | Integrated |

Episomal lines may also carry integrated copies in addition.

(ii) FISH analysis. (a) Probes.

Figure 1 shows a BamHI restriction endonuclease map of EBV, with the regions used as probes in the hybridization experiments indicated. EBV-specific probes were derived from cloned BamHI-digested fragments (BamHI W and BamHI K) of the B95-8 strain of EBV DNA, kindly provided by Lars Rymo, Gothenburg, Sweden (1). The 3.1-kb BamHI W fragment and the 5.1-kb BamHI K fragment were purified from the gels and used for FISH. Probes were labeled by nick translation with either biotinylated 16-dUTP (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), fluorescein–12-dUTP, or Texas red–5-dUTP (Dupont) with a BIONICK labeling kit (Gibco-BRL). Human chromosome X and four paints were labeled with cyanine 3 (Cy3) (CAMBIO, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

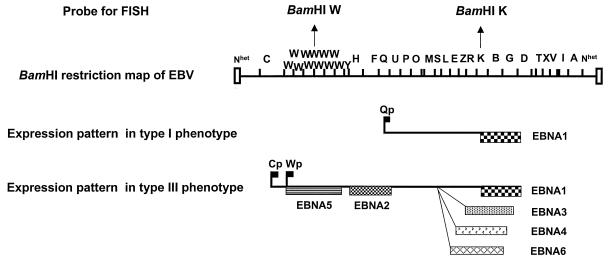

FIG. 1.

Patterns of viral gene expression and regulation in cells latently infected with EBV. Diagrams were adapted from references 21 and 26. A BamHI restriction endonuclease map of the 172-kb B95.8 EBV strain was used to assign promoter and exon positions (top). Two viral programs, designated type I and type III, are used alternatively in EBV-carrying B-cell lines and tumor biopsies. In type III, all six EBNA messages are spliced from a polycistronic message originating from alternative promoters in the W or C region (flags). In type I, only EBNA1 is expressed from a monocistronic message, initiated at the Qp promoter (flag) (29).

(b) Hybridization.

Hybridization was performed as described previously (31). Nuclear and chromosome preparations were rinsed for 10 min in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and dehydrated with 70 and 95% EtOH for 5 min each before air drying. For DNA-specific hybridization, RNase A (100 μg/ml in 2× SSC) treatment was done at 37°C for 1 h before hybridization. Slides were denatured for 2 to 3 min in 70% formamide–2× SSC at 70°C. This step was omitted for hybridization to RNA. Preparations were dehydrated with cold 70, 90, and 100% EtOH for 5 min each and air dried. For each sample, 50 ng of probe, 5 μg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA, and 20 μg of Escherichia coli tRNA were suspended in 5 μl of deionized formamide and heated at 70 to 80°C for 10 min. An equal volume of hybridization buffer was added, so that the final hybridization solution contained 50% formamide, 2× SSC, and 10% dextran sulfate (17). The slides were incubated at 37°C overnight.

(c) Detection.

Biotin-labeled DNA was detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated avidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) as described previously (24). Chromosomes and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The slides were examined with a Leica DMRBE microscope equipped with a cooled charge-coupled-device camera (Hamamatsu 4800) and filter sets specific for the fluorochromes (DAPI, FITC, and Texas red).

RESULTS

(i) EBV integration site.

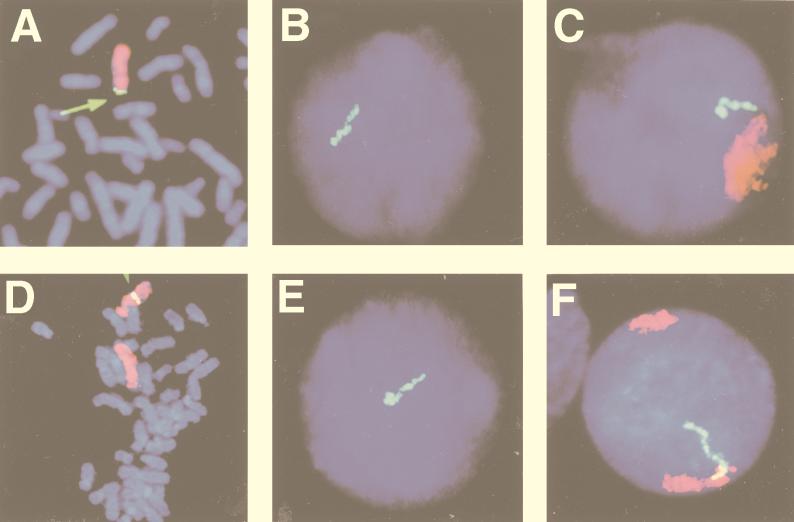

RNase A treatment followed by DNA denaturation and hybridization with the BamHI W sequence detected the viral integration site in the telomeric portion of Xp in Namalwa-Cl8 cells and in 4q25 in IB4-D cells (Fig. 2A and D). Corresponding signals were obtained in interphase nuclei (data not shown). These localizations were confirmed with chromosome X- and chromosome 4-specific probes (Fig. 2A and D).

FIG. 2.

FISH to metaphase chromosomes and nuclei of cells with integrated EBV DNA with the EBV BamHI W DNA probe. (A to C) Hybridization to cytogenetic preparations of Namalwa-Cl8 cells; (D to F) hybridization to LCL IB4-D. (A) Simultaneous hybridization to both viral (EBV BamHI W) DNA and chromosome X in denatured and RNase A-treated samples. Yellow signals (arrow) on each sister chromatid of chromosome X (red) indicates the localization of integrated EBV genomes in the telomeric region of Xp. The chromosome X-painting probe was labeled with Cy3 and the EBV BamHI W DNA was labeled with biotin and detected with FITC-conjugated avidin. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI. (B) Track of the EBV BamHI fragment W (BamHI W) RNA (green) within a nondenatured interphase nucleus. The EBV BamHI W DNA was labeled with biotin, and hybridization was detected with FITC-avidin. The nucleus was counterstained with DAPI. (C) Simultaneous hybridization of the BamHI W DNA probe and the chromosome X-specific probe in denatured samples indicates the X chromosome domain (red) and the BamHI W nuclear RNA (green) in a DAPI-stained nucleus. The chromosome X-painting probe was labeled with Cy3, and the EBV BamHI W DNA was labeled with biotin and detected with FITC-conjugated avidin. Note that the RNA track extends from the chromosome X interphase domain into a more peripheral position. (D) Simultaneous hybridization to viral (EBV BamHI W) DNA and chromosome 4 in denatured and RNase A-treated samples. Yellow signals on each sister chromatid on q25 of one chromosome 4 (red) indicate the localization of integrated EBV genomes. The chromosome 4-painting probe was labeled with Cy3, and the EBV BamHI W DNA was labeled with biotin and detected with FITC-conjugated avidin. Chromosomes were counterstained with DAPI. (E) Nuclear RNA from the BamHI W region of EBV (green) in nondenatured preparations. EBV BamHI W DNA was labeled with biotin, and hybridization was detected with FITC-conjugated avidin. The nucleus was counterstained with DAPI. Note the large accumulation of RNA at the end of the track. (F) Simultaneous hybridization of the BamHI W probe and the chromosome 4-specific probe in denatured samples indicate the two chromosome 4 domains (red) and the BamHI W nuclear RNA track (green) in a DAPI-stained nucleus of an IB4-D cell. Note that the RNA track extends from the chromosome 4 interphase domain across almost half of the nucleus.

(ii) Nuclear EBV-specific RNA detection in LCLs and in type I and type III BL lines. (a) Cell lines with integrated EBV DNA and type III latency (Namalwa-CL8 and IB4-D).

The EBV BamHI W probe was used to localize the complementary RNA sequences in the type III BL line Namalwa-Cl8 and in the LCL IB4-D, known to carry only integrated EBV DNA (6, 8, 11). Viral transcripts were detected in 90 to 92% of the cells in both lines. They were restricted to a single site in each nucleus (Fig. 2B and E). Accumulating transcripts appeared as bright curvilinear tracks, similar to the earlier description of Lawrence et al. (17). In large decondensed nuclei the tracks extended across almost half of the nucleus.

(b) Simultaneous detection of chromosome-specific nuclear domains containing EBV integration sites and BamHI W RNA tracks in Namalwa-Cl8 and IB4-D cells.

Namalwa-Cl8 and IB4-D cells were stained with chromosome X- and chromosome 4-specific probes, respectively. Hybridization solution containing a differently labeled BamHI W probe was applied in parallel. The BamHI W RNA tracks were regularly associated with chromosome X domains in Namalwa-Cl8 cells and with chromosome 4 domains in IB4-D cells (Fig. 2C and F). Analysis of over 100 Namalwa-Cl8 and IB4-D cells showed that 73 and 70% of BamHI W RNA tracks, respectively, appeared to be in direct contact with chromosome X and 4 domains, with no visible separation between the domain and the RNA.

(c) Simultaneous detection of BamHI K and BamHI W RNA in Namalwa-Cl8 and IB4-D cells.

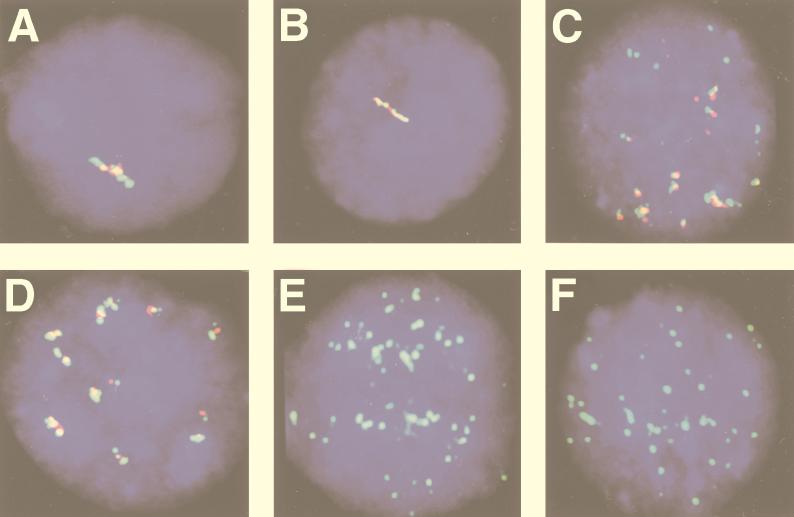

Two-color labeling experiments were performed with the BamHI K and BamHI W probes on nondenatured preparations. Both probes hybridized to the same nuclear foci in both cell lines (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 3.

Nuclear EBV-specific RNA detection in LCLs and in type I and type III BL cells. Two viral programs, designated type I and type III, are used alternatively in EBV-carrying B-cell lines and tumor biopsies. In type III, all six EBNA messages are spliced from a polycistronic message. In type I, only EBNA1 is expressed from a monocistronic message (Fig. 1). A biotin- or Texas red-labeled EBV BamHI K DNA probe that can hybridize to both the monocistronic and the polycistronic message and a Texas red- or biotin-labeled BamHI W DNA probe that can hybridize to the polycistronic but not to the monocistronic message were used to distinguish between cells that use type III and type I programs in two-color FISH. The biotin-labeled probes were detected with FITC-conjugated avidin. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. (A) Simultaneous detection of EBV BamHI K (red) and BamHI W (green) RNA tracks on a nucleus from the type III BL line Namalwa-Cl8. Both probes hybridized to the same nuclear foci. (B) Simultaneous detection of EBV BamHI K (green) and BamHI W (red) RNA tracks on a nucleus from an LCL IB4-D cell. (C) Two-color FISH with EBV BamHI K (green) and BamHI W (red) probes on a nucleus of the type III BL line MUTU III with multiple episomal EBV shows that both probes hybridized to the same nuclear foci, creating the appearance of two-colored tracks. (D) Simultaneous detection of EBV BamHI K (red) and BamHI W (green) RNA tracks on a nucleus of an LCL-970402 cell that carries numerous episomal genomes. FISH shows many two-colored RNA foci or tracks. (E and F) Detection of BamHI K (green) but not BamHI W RNA in the type I BL lines Rael (E) and MUTU I (F) in two-color experiments.

(d) Simultaneous detection of BamHI K and BamHI W RNAs in cells with multiple episomal EBV DNA copies.

Cell lines with episomal EBV-DNA such as the type III BL line MUTU III and LCL-970402 gave positive signals with both BamHI W and BamHI K. Two-color fluorescence showed that both probes hybridized to the same nuclear foci, creating the appearance of elongated two-colored dots (Fig. 3C and D). We have found that the nuclear RNA tracks were shorter in cell lines carrying episomal EBV genomes (i.e., MUTU and LCLs) than in cell lines with an integrated EBV genome (i.e., Namalwa-Cl8 and IB4-D). This may be related to the level of transcription or to the location of the integrated EBV DNA in a more internal nuclear compartment.

(e) Detection of BamHI K but not BamHI W RNA in type I BL lines and heterogeneous expression in the LCL IARC-171.

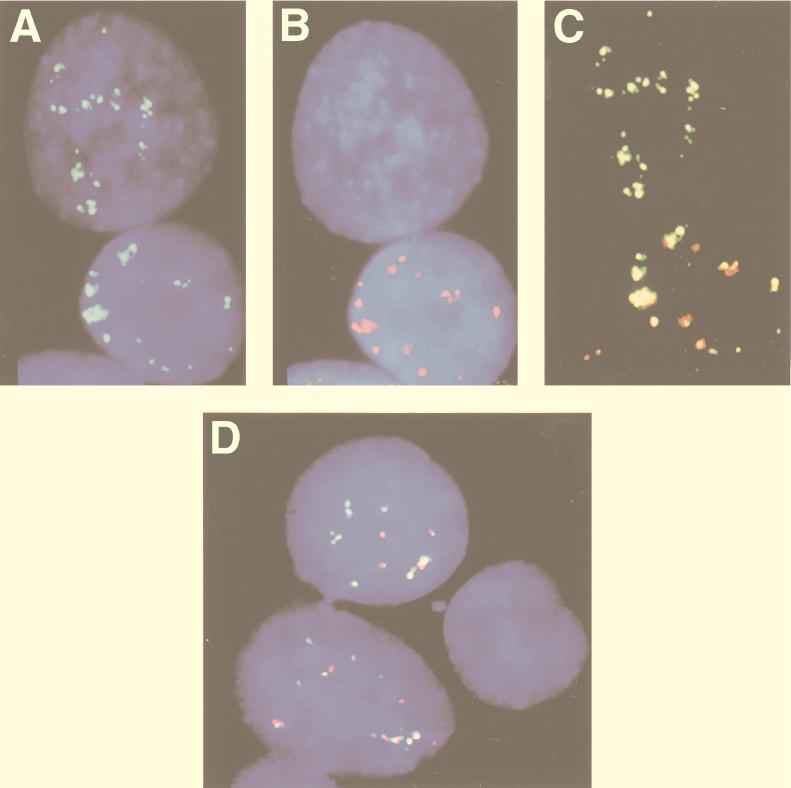

Type I BL lines (MUTU I and Rael), which carry episomal EBV, hybridize only with the BamHI K but not the BamHI W probe in two-color experiments (Fig. 3E and F). In LCL-970402, two positive signals were found in 96% of the cells while no positive signals were found in 4% of the cells (Fig. 4D). In IARC-171 three categories of cells were observed. Ninety percent of the cells hybridized with both probes, 5% hybridized with BamHI K but not BamHI W (Fig. 4A to C), and 5% failed to hybridize with either one of the two probes. All three categories of cells appeared equally viable. These results suggest that a proportion of the IARC-171 but not the LCL-970402 cells may shift from a type III to a type I program and also raise the question of whether a latency 0 program exists as well. We cannot entirely exclude technical reasons for the occasional lack of hybridization signals. We have tried to minimize this problem, however, by scoring only regions where the signal-positive and signal-negative cells were close to each other, as exemplified in Fig. 4. The difference between LCL-970402 and IARC-171 also speaks against the technical artifact.

FIG. 4.

Heterogenous EBV RNA expression in LCLs. The BamHI W probe was labeled with Texas red, and the BamHI K probe was labeled with biotin and detected with FITC-conjugated avidin. (A to C) Two-color FISH using EBV BamHI K (green) and BamHI W (red) probes on nuclei of cells of the LCL IARC-171 show two-colored (green and red) tracks in one nucleus and only green (BamHI K RNA) but not red (BamHI W RNA) tracks in the other nucleus, suggesting that a proportion of the cells may shift from a type III to a type I program. (C) Merged images of the red and green signals. Note that the signals of the upper nucleus are green but that those of the lower one have two colors. (D) Simultaneous detection of EBV BamHI K (green) RNA and BamHI W (red) RNA in nuclei of LCL-970402 cells. One of the nuclei failed to hybridize with either one of the two probes, suggesting that the latency 0 program may exist.

DISCUSSION

Latent EBV genomes are differentially expressed in different cell types, as was clearly stated in the introduction. We found that a double-RNA-track FISH technique can distinguish between cells using a type I or a type III program. This finding may permit the study of EBV program switches in LCLs and other EBV-carrying cell populations in vitro and, at a later stage, hopefully in vivo as well. It may open the way to the analysis of program switches during primary infection as in mononucleosis. Immunoblastic transformation and rapid proliferation is followed by immune rejection, mediated largely by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, targeted against major histocompatibility complex class I-associated peptides derived from EBNA2 to -6 or the LMPs. EBNA1 is not a rejection target, due to the impairment of its processing by the glycine-alanine repeat (20). The first phase raises the number of virus-carrying cells to a ceiling level, prior to rejection. The rejection response secures the survival of the host. The survival of the virus is secured by its persistence in resting B lymphocytes that express EBNA1 only, do not expand, and are not rejected. A latently infected reservoir is established in all infected individuals, including immunodefective hosts with large immunoblastomas that have been successfully treated by adoptive transfer of T cells.

We have previously postulated (14) that a small fraction of the proliferating immunoblast population regularly switches to a resting B-cell phenotype, perhaps by a process akin to the generation of memory B cells, with a concomitant program switch from III to I. The opposite program switch, from I to III, is well known. It occurs in BL type I lines drifting to type III and can be induced in stable type I BL cells by 5-azacytidine-induced DNA demethylation (22). So far, the III-to-I switch is only a postulate that has been inaccessible to direct study. We hope that the method described in this paper will open the way to direct experimentation on this important problem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank László Székely (MTC, KI) for LCL-970402. We gratefully appreciate the technical assistance of Katalin Benedek, Hajnalka Kiss, Agneta Manneborg Sandlund, and Ying Yang (MTC, KI).

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society (Cancerfonden), the Karolinska Institute, the Swedish Medical Research Council, and the Cancer Research Institute/Cancer Foundation, New York, N.Y.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrand J R, Rymo L, Walsh J L, Bjorck E, Lindhal T, Griffin B E. Molecular cloning of the complete Epstein-Barr virus genome as a set of overlapping restriction endonuclease fragments. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:2999–3014. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter K C, Lawrence J B. DNA and RNA within the nucleus: how much sequence-specific spatial organization? J Cell Biochem. 1991;47:124–129. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240470205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen F, Zou J Z, di Renzo L, Winberg G, Hu L F, Klein E, Klein G, Ernberg I. A subpopulation of normal B cells latently infected with Epstein-Barr virus resembles Burkitt lymphoma cells in expressing EBNA-1 but not EBNA-2 or LMP1. J Virol. 1995;69:3752–3758. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3752-3758.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirks R W, Daniel K C, Raap A K. RNAs radiate from gene to cytoplasm as revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2565–2572. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.7.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fåhraeus R, Fu H L, Ernberg I, Finke J, Rowe M, Klein G, Falk K, Nilsson E, Yadav M, Busson P, Tursz T, Kallin B. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded proteins in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:329–338. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gargano S, Caporossi D, Gualandi G, Calef E. Different localization of Epstein-Barr virus genome in two subclones of the Burkitt lymphoma cell line Namalwa. Genes Chromosome Cancer. 1992;4:205–210. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870040303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory C D, Rowe M, Rickinson A B. Different Epstein-Barr virus-B cell interactions in phenotypically distinct clones of a Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1481–1495. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-7-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henderson A, Ripley S, Heller M, Kieff E. Chromosome site for Epstein Barr virus DNA in a Burkitt tumor cell line and in lymphocytes growth-transformed in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1987–1991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.7.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herbst H, Stein H, Niedobitek G. Epstein-Barr virus and CD30+ malignant lymphomas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1993;4:191–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang S, Spector D L. Nascent pre-mRNA transcripts are associated with nuclear regions enriched in splicing factors. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2288–2302. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12a.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurley E A, Klaman L D, Agger S, Lawrence J B, Thorley-Lawson D A. The prototypical Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line IB4 is an unusual variant containing integrated but not episomal viral DNA. J Virol. 1991;65:3958–3963. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3958-3963.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Month T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2343–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 13.King W, Thomas-Powell A L, Raab-Traub N, Hawke M, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus RNA. V. Viral RNA in a restringently infected, growth-transformed cell. J Virol. 1980;36:506–518. doi: 10.1128/jvi.36.2.506-518.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein G. Epstein-Barr virus strategy in normal and neoplastic B cells. Cell. 1994;77:791–793. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein G, Dombos L, Gothoskar B. Sensitivity of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) producer and non-producer human lymphoblastoid cell lines to superinfection with EB-virus. Int J Cancer. 1972;10:44–57. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawrence J B, Carter K C, Xing X. Probing functional organization within the nucleus: is genome structure integrated with RNA metabolism? Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:807–818. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence J B, Singer R H, Marselle L M. Highly localized tracks of specific transcripts within interphase nuclei visualized by in situ hybridization. Cell. 1989;57:493–502. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90924-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenoir G M, Vuillaume M, Bonnardel C. The use of lymphomatous and lymphoblastoid cell lines in the study of Burkitt’s lymphoma. IARC (Int Agency Res Cancer) Sci Publ. 1985;60:309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lestou V S, Strehl S, Lion T, Gadner H, Ambros P F. High-resolution FISH of the entire integrated Epstein-Barr virus genome on extended human DNA. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;74:211–217. doi: 10.1159/000134416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levitskaya J, Coram M, Levitsky V, Imreh S, Steigerwald-Mullen P M, Klein G, Kurilla M G, Masucci M G. Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1. Nature. 1995;375:685–688. doi: 10.1038/375685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masucci M G, Ernberg I. Epstein-Barr virus: adaptation to a life within the immune system. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90599-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masucci M G, Contreras-Salazar B, Ragnar E, Falk K, Minarovits J, Ernberg I, Klein G. 5-Azacytidine up regulates the expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA-2) through EBNA-6 and latent membrane protein in the Burkitt’s lymphoma line Rael. J Virol. 1989;63:3135–3141. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3135-3141.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pallesen G, Hamilton-Dutoit S J, Zhou X. The association of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) with T cell lymphoproliferations and Hodgkin’s disease: two new developments in the EBV field. Adv Cancer Res. 1993;62:179–239. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60319-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinkel D, Straume T, Gray J W. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2934–2938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raap A K, van de’Rijke F M, Dirks R W, Sol C J, Boom R, van der Ploeg M. Bicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization to intron and exon mRNA sequences. Exp Cell Res. 1991;197:319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Month T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2397–2476. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosbash M, Singer R H. RNA travel: tracks from DNA to cytoplasm. Cell. 1993;75:399–401. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90373-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe M, Rowe D T, Gregory C D, Young L S, Farrell P J, Rupani H, Rickinson A B. Differences in B cell growth phenotype reflect novel patterns of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in Burrkitt’s lymphoma cells. EMBO J. 1987;6:2743–2751. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaefer B C, Strominger J L, Speck S H. Redefining the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen EBNA-1 gene promoter and transcription initiation site in group I Burkitt lymphoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10565–10569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spector D L. Nuclear organization of pre-mRNA processing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:442–447. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90009-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Székely, L. Unpublished data.

- 31.Szeles A, Bajalica S, Lindblom A, Lushnikova T, Kashuba V I, Imreh S, Nordenskjöld M, Klein G, Zabarovsky E R. Mapping of a new MAP kinase activated protein kinase gene (3pK) to human chromosome band 3p21.2 and ordering of 3pK and two cosmid markers in 3p22-p21 tumor suppressor region by two color FISH. Chromosome Res. 1996;4:310–313. doi: 10.1007/BF02263683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing Y, Lawrence J B. Preservation of specific RNA distribution within the chromatin-depleted nuclear substructure demonstrated by in situ hybridization coupled with biochemical fractionation. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:1055–1063. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.6.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xing Y, Lawrence J B. Nuclear RNA tracks: structural basis for transcription and splicing? Trends Cell Biol. 1993;3:346–353. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90105-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xing Y, Johnson C V, Dobner P R, Lawrence J B. Higher level organization of individual gene transcription and RNA splicing. Science. 1993;259:1326–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.8446901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]