Dear Editor,

The global prevalence of type 2 diabetes and obesity, affecting over 507 million1 and 890 million2 individuals, respectively, underscores the urgent need for more effective treatments. The most successful treatments currently available include glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), exemplified by semaglutide (approved in 2017, $19.9 billion sales in 2023)3 and tirzepatide (approved in 2022, $5.3 billion sales in 2023)4. Unlike semaglutide which solely activates GLP-1R (one of the three pivotal receptors regulating glucose homeostasis), tirzepatide also activates glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor (GIPR) to enhance metabolic benefits with reduced side-effects5. However, both medications do not target glucagon (GCG) receptor (GCGR). Recently, retatrutide (also known as LY3437943)6–9 has shown impressive efficacy in obesity treatment through triple agonism at GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR. Compared to the corresponding endogenous hormones, retatrutide is more potent at GIPR by a factor of 8.9, and less potent at GCGR and GLP-1R by factors of 0.3 and 0.4, respectively7 (Fig. 1a). Retatrutide induces greater body weight losses in obese mice than tirzepatide, due to an increased energy expenditure through GCGR activation6. In a phase 2 obesity trial, retatrutide demonstrated an average weight loss of 17.5% at 24 weeks and 24.2% at 48 weeks in the 12 mg dose group7. Additionally, in a phase 2 trial targeting type 2 diabetes, retatrutide demonstrated significant improvements in glycemic control and substantial weight reduction, maintaining a safety profile comparable to certain approved GLP-1RAs8 (Supplementary Table S1). These results support the rationale of developing retatrutide as an alternative to semaglutide and/or tirzepatide5. Indeed, phase 3 clinical trials of retatrutide for type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and obesity are presently underway (Supplementary Table S2)10. To understand the multiplexed pharmacological actions of retatrutide, we used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to determine the structures of GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR bound to retatrutide.

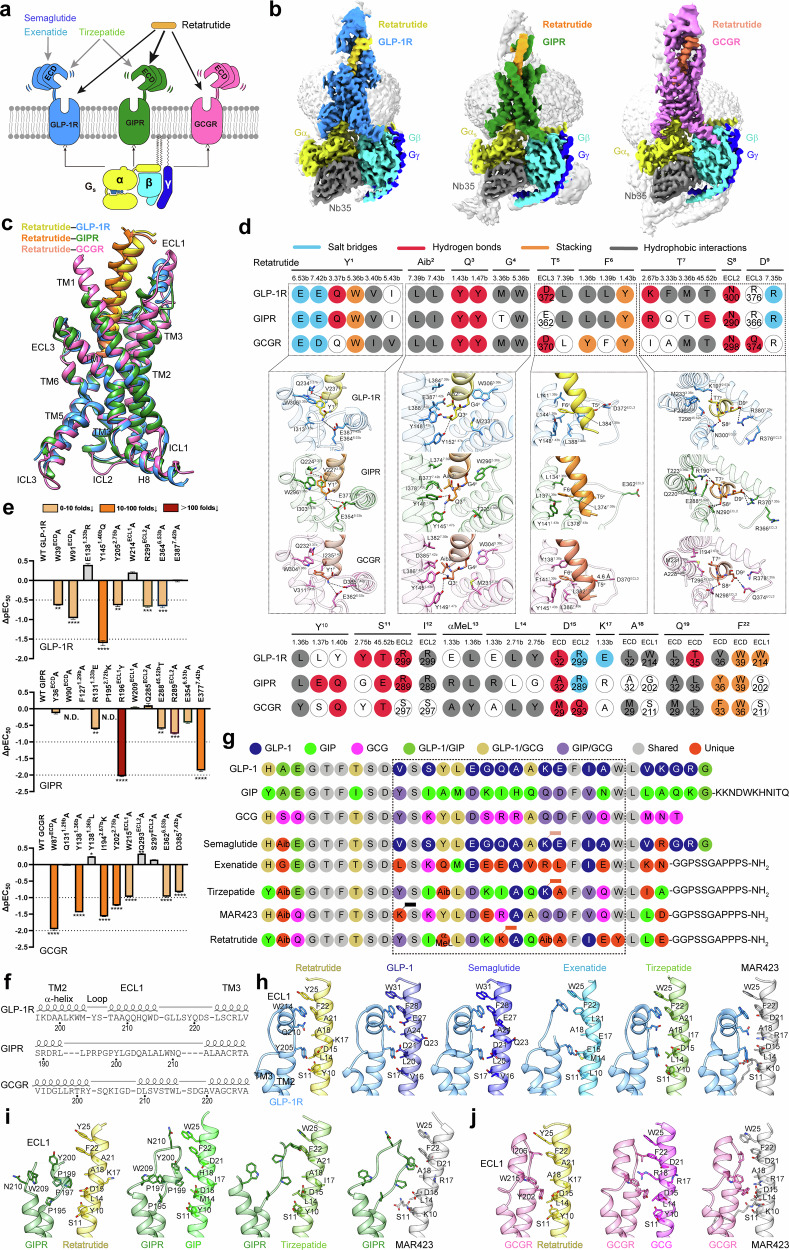

Fig. 1. Molecular recognition of retatrutide by GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR.

a Retatrutide (LY3437943) possesses combinatorial agonism at GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR, distinct from the approved GLP-1R agonists (such as semaglutide and exenatide) and GLP-1R/GIPR dual agonist tirzepatide. b Cryo-EM maps of retatrutide-bound GLP-1R (left), GIPR (middle) and GCGR (right) in complex with Gs. The colored cryo-EM density maps are shown at the thresholds of 0.110, 0.107 and 0.134 for the retatrutide–GLP-1R–Gs, retatrutide–GIPR–Gs and retatrutide–GCGR–Gs complexes, respectively. The GLP-1R is shown in dodger blue, GIPR in forest green, GCGR in hot pink, GLP-1R-bound retatrutide in gold, GIPR-bound retatrutide in orange, GCGR-bound retatrutide in coral, Gαs in yellow, Gβ subunit in cyan, Gγ subunit in blue and Nb35 in gray. c Structural comparison of retatrutide–GLP-1R, retatrutide–GIPR and retatrutide–GCGR. Receptor ECD and G protein are omitted for clarity. d Schematic diagram of retatrutide recognition mode in GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR, described by fingerprint strings encoding different interaction types of the surrounding residues in each receptor. Close-up views of the interactions are shown for the N-terminal nine residues of retatrutide. The polar contacts are shown as black dashed lines. Receptor residues are labeled with class B1 GPCR numbering and colored sky blue for salt bridge, red for hydrogen bond, orange for stacking and gray for hydrophobic interactions. Residues that show no interaction with retatrutide are displayed as white circles. e Effects of GLP-1R (top), GIPR (middle), and GCGR (bottom) mutations on retatrutide-induced cAMP accumulation. Bars represent differences in the calculated retatrutide potency (pEC50) for representative mutants relative to the wild-type (WT). Data are colored according to the extent of effect. Data shown are from at least three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. All data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. N.D., values that could not be determined due to incomplete curve fits. f The distinct secondary structures of the ECL1 of GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR. g Amino acid sequence comparison of endogenous hormones, representative dual and triple agonists. Residues are colored according to sequence conservation among GLP-1, GIP and GCG. Aib α-amino isobutyric acid, αMeL α-methyl L-leucine. Semaglutide, tirzepatide, peptide 20 (MAR423) and retatrutide are acylated with various fatty diacid moieties via a linker connected to the lysine residues at the positions of 20, 20, 10 and 17, respectively. h Comparison of the interactions between GLP-1R ECL1 and representative peptide agonists including retatrutide, GLP-1 (PDB ID: 6X18), semaglutide (PDB ID: 7KI0), exenatide (PDB ID: 7LLL), tirzepatide (PDB ID: 7FIM) and peptide 20 (PDB ID: 7VBH). i Comparison of the interactions between GIPR ECL1 and representative peptide agonists including retatrutide, GIP (PDB ID: 7DTY), tirzepatide (PDB ID: 7FIY) and peptide 20 (PDB ID: 7FIN). j Comparison of the interactions between GCGR ECL1 and representative peptide agonists including retatrutide, GCG (PDB ID: 6LMK) and peptide 20 (PDB ID: 7V35).

Following our previously reported protocols with the NanoBiT tethering strategy11, the structures of retatrutide–GLP-1R–Gs, retatrutide–GIPR–Gs and retatrutide–GCGR–Gs were determined using the single-particle cryo-EM with overall resolutions of 2.68 Å, 3.26 Å and 2.84 Å, respectively (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Figs. S1, S2 and Table S3). Apart from the α-helical domain of Gαs and the extracellular domain (ECD) of GIPR, the presence of retatrutide, each individual receptor and heterotrimeric Gs in the respective complexes were clearly visible in all three cryo-EM maps, thereby allowing unambiguous modeling of the secondary structure and side-chain orientation of all major components (Supplementary Fig. S3). Several segments in the ECD of GCGR, the stalk between ECD and transmembrane helix 1 (TM1) of GLP-1R (residues 130–135), extracellular loop 1 (ECL1) of GIPR (residues 202–207), and intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) of GLP-1R and GIPR (residues 338–343 and 330–333, respectively) were poorly resolved and not modeled in the structures.

Retatrutide adopts a single continuous helix that penetrates the core of the receptor transmembrane domain (TMD) via its N-terminal segment (residues 1–13), while its C-terminal segment (residues 14–30) interacts with the N-terminal α-helix of the ECD, the extracellular tip of TM1 and ECL1 (Fig. 1b–e). Although the overall structures of retatrutide-bound GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR are highly similar, with Cα root mean square deviation (RMSD) values of 0.88–0.93 Å, unique structural features were noted at ECL1, ECL3 and the extracellular tips of TM1, TM3 and TM7, displaying receptor-specific positions and conformations. Specifically, the extracellular half of TM7 in GCGR shifts outward by 4.56 Å and 3.02 Å (measured by the Cα of R7.35b, class B1 GPCR numbering in superscript12), facilitating the outward orientation of retatrutide’s N-terminus by 2.84 Å and 2.61 Å (measured by the Cα of Y1P, P in superscript indicates peptide residue) compared to these residues at retatrutide–GLP-1R and retatrutide–GIPR structures, respectively. In GLP-1R and GCGR, ECL1 forms a short α-helix structure adjacent to the extracellular tips of TM2 in GLP-1R and TM3 in GCGR (Fig. 1f). Conversely, the ECL1 of GIPR adopts an unwound and relaxed loop conformation, likely due to the presence of three proline residues (P195, P197 and P199). This conformation causes retatrutide to straighten, shifting its tip towards the TMD core by 4.29 Å and 4.13 Å (measured by the Cα of L27P), relative to GLP-1R and GCGR, respectively.

Analyzing molecular recognition of retatrutide by GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR highlights that the triple agonism is achieved through a combination of maintaining common interactions with conserved residues and accommodating receptor-specific residues with variable contacts primarily in the upper half of the TMD pocket (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. S4 and Table S4). These common interactions involve two salt bridges with E6.53b and E/D7.42b (via the positively charged N-terminal nitrogen atom of Y1P), stacking interactions with W39GLP-1R/W39GIPR/W36GCGR (via F22P), Y1.43b (via F6P) and W5.36b (via Y1P), multiple hydrogen bonds with L32GLP-1R/A32GIPR/M29GCGR (via D15P), Y1.43b (via Q3P), Y1.47b (via Q3P), T/E45.52b (via S11P) and N300GLP-1R/N290GIPR/N298GCGR (via S8P), along with extensive hydrophobic contacts with L/Y1.36b (via Y10P and αMeL13P), I/V3.40b (via Y1P), W5.36b (via G4P), L7.39b and I/L7.43b (via Aib2P). Consistently, alanine mutations at E6.53b decreased retatrutide-induced cAMP signaling potency by 3.6-fold for GLP-1R, 1.6-fold for GIPR and 8.3-fold for GCGR, while at E/D7.42b, potency decreased by 71.6-fold for GIPR and 5.8-fold for GCGR (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table S5). Regarding receptor-specific interactions, the retatrutide–GLP-1R complex displays three salt bridges (D9P−R7.35b, D15P–R299ECL2 and K17P–E1.33b), with the first two also present in the retatrutide–GIPR complex, while the last one is absent in GIPR due to the positively charged R1311.33b. Additionally, in GLP-1R and GIPR, K/R2.67b and R299GLP-1R/R289GIPR in ECL2 form two hydrogen bonds with T7P and S11P, respectively. Conversely, equivalent residues in GCGR (I1942.67b and S297ECL2) are unable to form these hydrogen bonds. These observations were supported by our mutagenesis studies, where mutations R299ECL2A in GLP-1R, R289ECL2A in GIPR and I1942.67bK in GCGR caused variable decreases in retatrutide potency (by 3.7-fold, 4.6-fold and 36.0-fold, respectively), while S297ECL2A in GCGR slightly increased retatrutide potency. Of note, E1381.33bR in GLP-1R and R1311.33bE in GIPR modestly increased and decreased the potency of retatrutide, respectively, indicating the receptor-specific adaptability of peptide recognition at this site (Fig. 1e). To compensate, retatrutide establishes GCGR-specific interactions including stacking with F33ECD (via F22P) and Y1381.36b (via F6P), and three hydrogen bonds with Q1421.40b (via Y10P), Q293ECL2 (via D15P) and Q374ECL3 (via D9P). The Y1381.36bA mutation in GCGR greatly decreased the potency of retatrutide-induced cAMP signaling by 26.9-fold, while Y1381.36bL moderately increased it, suggesting the hydrophobic interactions at 1.36b play a crucial role (Fig. 1e). In GIPR, Q1381.40b and two glutamic acid residues (E1351.37b and E28845.52b) make three hydrogen bonds with Y10P and T7P, while F22P and αMeL13P/L14P in retatrutide interact with Y36ECD and R1311.33b through stacking and hydrophobic contacts, respectively. Consistently, the E28845.52bT mutation in GIPR reduced retatrutide-induced cAMP accumulation by 3.0-fold. Moreover, R196ECL1Y diminished retatrutide potency by 107.7-fold, whereas P1952.72bK markedly decreased GIPR-mediated cAMP accumulation, supporting a key role of GIPR ECL1 in retatrutide agonism (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Fig. S5 and Table S5).

Sequence comparison among endogenous hormones, approved drugs and triple agonists revealed that the peptide sequence is conserved in the N-terminal region (residues 4–9), with variations primarily occurring in the middle region (residues 10–21) (Fig. 1g). This middle region is specifically recognized by ECL1, ECL2, and the extracellular tip of TM1, all of which exhibit receptor-specific conformation and structural flexibility (Fig. 1g–j). For instance, ECL1 that primarily interacts with six peptide positions (11P, 14P, 15P, 18P, 22P and 25P) maintains a robust short α-helix adjacent to TM2 for GLP-1R and TM3 for GCGR, respectively, regardless of the bound peptides (Fig. 1h–j). Therefore, the interacting peptide must possess complementary amino acids at specific positions to align with the rigid ECL1 structure to effectively bind and activate GLP-1R or GCGR. In contrast, the ECL1 of GIPR displays notable flexibility, accommodating a variety of conformations to recognize peptides and allowing for sequence variability. This requirement of ECL1 recognition drives the above six key positions in dual or triple agonists (tirzepatide, peptide 20 (MAR423), and retatrutide) to use amino acids similar to those in GLP-1/GCG, while the other positions in the middle region show considerable variability (Fig. 1g). Of note, leveraging the two conserved segments (residues 4–9, 11, 14, 15, 18, 22 and 25), retatrutide and peptide 20 present a distinct design strategy, developed from the GIP and GCG backbones, respectively, to allow simultaneous agonism at the three pivotal receptors1,13. These findings underscore the potential for peptide sequence optimization to fine-tune receptor selectivity or balanced activation, providing tailored approaches for treating different diseases14.

In conclusion, our study provides valuable structural insights into the mechanism underlying the superior clinical efficacy of retatrutide, a unimolecular triple agonist simultaneously activating GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR. The cryo-EM structures of retatrutide-bound GLP-1R, GIPR and GCGR reveal a combination of conserved peptide–receptor interactions and receptor-specific conformations, particularly in ECL1, that enables retatrutide to execute agonism at multiple receptors. Comparison with the binding modes of other dual and triple agonists highlight that the N-terminal and C-terminal regions of the peptide confer receptor selectivity, whereas the middle region offers opportunities for sequence optimization to refine receptor engagement, thereby presenting a useful template for designing better unimolecular therapeutics.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jie Li, Yanyan Chen, Xianyue Chen and Yang Li for technical assistance. The cryo-EM data were collected at the Cryo-Electron Microscopy Research Center, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences. This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273961, 82073904, 81872915 to M.-W.W., 82273985, 82121005, 81973373 to D.Y., 32200576, 32071203 to L.-H.Z., 82121005 to H.E.X. and 82204474 to F.Z.); National Science & Technology Major Project of China — Key New Drug Creation and Manufacturing Program (2018ZX09735–001 to M.-W.W. and 2018ZX09711002–002–005 to D.Y.); STI2030-Major Project (2021ZD0203400 to Q.Z. and 2022ZD0213000 to F.Z.); Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2022M710806 to Z.C. and 2022M713266 to F.Z.); Postdoctoral Innovative Talent Support Plan of China (BX20220070 to Z.C.); Hainan Provincial Major Science and Technology Project (ZDKJ2021028 to D.Y. and Q.Z.); the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1800804 to D.Y. and 2022YFC2703105 to H.E.X.); CAS Strategic Priority Research Program (XDB37030103 to H.E.X.); Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2019SHZDZX02 to H.E.X.); State Key Laboratory of Drug Research (SKLDR-2023-TT-04 to H.E.X.); Shanghai Municipality Science and Technology Development Fund (21JC1401600 to D.Y.); Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (23XD1400900 to D.Y.) and Shanghai Sailing Program (22YF1457200 to F.Z.).

Author contributions

Wenzhuo L., Z.C., L.-H.Z., Wenxin L. and F.Z. performed research and participated in manuscript preparation; Wenzhuo L., Z.C., Q.Z. L.-H.Z. and Q.Y. conducted map calculation and built the models; Q.Z. and Wenzhuo L. carried out structural analyses; L.-H.Z. and H.E.X. assisted in data analysis; Q.Z., Wenzhuo L., Z.C. and M.-W.W. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all co-authors; M.-W.W. and D.Y. initiated the project and supervised the studies.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors and/or included in the manuscript or Supplementary Information. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes: 8YW3 (retatrutide−GLP-1R−Gs complex), 8YW4 (retatrutide−GIPR−Gs complex) and 8YW5 (retatrutide−GCGR−Gs complex); and the electron microscopy maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession codes: EMD-39621 (retatrutide−GLP-1R−Gs complex), EMD-39622 (retatrutide−GIPR−Gs complex) and EMD-39623 (retatrutide−GCGR−Gs complex).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Wenzhuo Li, Qingtong Zhou, Zhaotong Cong.

Contributor Information

Li-Hua Zhao, Email: zhaolihuawendy@simm.ac.cn.

Dehua Yang, Email: dhyang@simm.ac.cn.

Ming-Wei Wang, Email: mwwang@simm.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41421-024-00700-0.

References

- 1.Ong KL, et al. Lancet. 2023;402:203–234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesityand-overweight (2024).

- 3.Buntz, B. https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/glp-1-receptor-agonist-clinical-trials-semaglutide-leads/ (2024).

- 4.https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-reports-strong-fourth-quarter-2023-financial-results-and (2024).

- 5.Doggrell SA. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2023;32:997–1001. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2023.2283020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coskun T, et al. Cell Metab. 2022;34:1234–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jastreboff AM, et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023;389:514–526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2301972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenstock J, et al. Lancet. 2023;402:529–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urva S, et al. Lancet. 2022;400:1869–1881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaur, M. & Misra, S. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 80, 669–676 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhao F, et al. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1057. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28683-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wootten, D., Simms, J., Miller, L. J., Christopoulos, A. & Sexton, P. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA110, 5211–5216 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Finan B, et al. Nat. Med. 2015;21:27–36. doi: 10.1038/nm.3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakubowska A, Roux CWL, Viljoen A. Endocrinol. Metab. (Seoul.) 2024;39:12–22. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2024.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the authors and/or included in the manuscript or Supplementary Information. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes: 8YW3 (retatrutide−GLP-1R−Gs complex), 8YW4 (retatrutide−GIPR−Gs complex) and 8YW5 (retatrutide−GCGR−Gs complex); and the electron microscopy maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession codes: EMD-39621 (retatrutide−GLP-1R−Gs complex), EMD-39622 (retatrutide−GIPR−Gs complex) and EMD-39623 (retatrutide−GCGR−Gs complex).