Abstract

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis, a condition that remains relatively underrecognized, has garnered increasing research focus in recent years. This scientific interest has catalyzed advancements in diagnostic methodologies, enabling comprehensive clinical and molecular profiling. Such progress facilitates the development of personalized treatment strategies, marking a significant step toward precision medicine for these patients.

Bronchiectasis poses significant diagnostic challenges in both clinical settings and research studies. While computed tomography (CT) remains the gold standard for diagnosis, novel alternatives are emerging. These include artificial intelligence-powered algorithms, ultra-low dose chest CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, all of which are becoming recognized as feasible diagnostic tools.

The precision medicine paradigm calls for refined characterization of bronchiectasis patients by analyzing their inflammatory and molecular profiles. Research into the underlying mechanisms of inflammation and the evaluation of biomarkers such as neutrophil elastase, mucins, and antimicrobial peptides have led to the identification of distinct patient endotypes. These endotypes present variable clinical outcomes, necessitating tailored therapeutic interventions. Among these, eosinophilic bronchiectasis is notable for its prevalence and specific prognostic factors, calling for careful consideration of treatable traits.

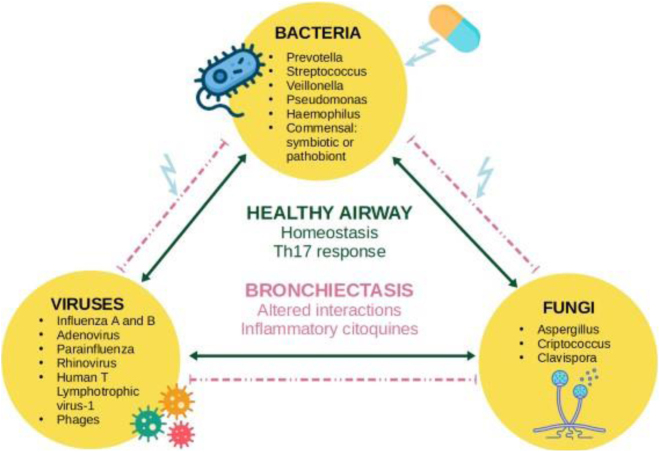

A deeper understanding of the microbiome's influence on the pathogenesis and progression of bronchiectasis has inspired a holistic approach, which considers the multibiome as an interconnected microbial network rather than treating pathogens as solitary entities. Interactome analysis therefore becomes a vital tool for pinpointing alterations during both stable phases and exacerbations.

This array of innovative approaches has revolutionized the personalization of treatments, incorporating therapies such as inhaled mannitol or ARINA-1, brensocatib for anti-inflammatory purposes, and inhaled corticosteroids specifically for patients with eosinophilic bronchiectasis.

Keywords: Bronchiectasis, Lung microbiome, Bronchiectasis endotypes

Abstract

Las bronquiectasias no fibrosis quística han atraído una creciente atención en investigación. Este interés científico ha catalizado avances en las metodologías de diagnóstico, permitiendo realizar perfiles clínicos y moleculares integrales. Este progreso facilita el desarrollo de estrategias de tratamiento personalizadas y marca un paso significativo hacia la medicina de precisión.

Desde el punto de vista diagnóstico, las bronquiectasias plantean desafíos importantes en entornos clínicos y de investigación. Si bien la TC es el gold standard, están surgiendo nuevas alternativas. Entre ellas, algoritmos de inteligencia artificial, TC de tórax de dosis ultrabajas y técnicas de resonancia magnética.

La medicina de precisión aboga por la caracterización de pacientes mediante análisis de perfiles inflamatorios y moleculares. Las investigaciones sobre mecanismos subyacentes de inflamación y la evaluación de biomarcadores como la elastasa de neutrófilos, mucinas y péptidos antimicrobianos, han llevado a la identificación de endotipos de pacientes. Estos endotipos exhiben resultados clínicos variables, requiriendo intervenciones terapéuticas personalizadas. La bronquiectasia eosinofílica destaca por su prevalencia y factores pronósticos específicos, exigiendo consideración de los rasgos tratables.

Una comprensión profunda de la influencia del microbioma en la patogénesis y progresión de las bronquiectasias inspira un enfoque holístico. Considera el multibioma como una red microbiana interconectada, no entidades solitarias. El análisis del interactoma se convierte en una herramienta vital para identificar alteraciones durante fases estables y exacerbaciones.

Este conjunto de enfoques innovadores revoluciona la personalización de los tratamientos, incorporando terapias como manitol inhalado o ARINA-1, brensocatib con fines antiinflamatorios y corticosteroides inhalados específicos para pacientes con bronquiectasias eosinofílicas.

Palabras clave: Bronquiectasias, Microbioma pulmonar, Endotipos de bronquiectasias

Are there any recent advancements or changes in the diagnostic approach to bronchiectasis?

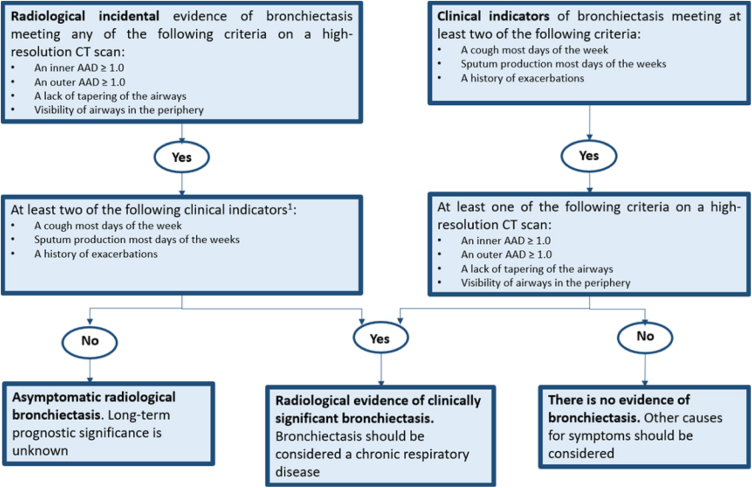

The variety of diseases associated with bronchiectasis, along with the absence of standardized definitions, has presented challenges both in clinical practice and in clinical trials for treatments targeting this condition. Accordingly, criteria and definitions for the radiological and clinical diagnosis of bronchiectasis in adults have recently been proposed. This involves integrating clinical and radiological data into a straightforward and informative flowchart. The primary objective is to facilitate the diagnosis of bronchiectasis as a chronic disease, particularly in the context of clinical trials1, 2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Defining clinically significant bronchiectasis. Identification of at least 2 criteria is intended for clinical trials while the presence of even 1 might be enough in clinical practice. AAD: airway-artery diameter ratio; CT: computed tomography.

Adapted from Aliberti et al.1

In the radiological study of bronchiectasis using high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), which remains the gold standard for its diagnosis, conducting a comprehensive visual and qualitative analysis of the intricate morphological changes in the airways and vascular trees can be challenging. However, volumetric helical chest CT has emerged as an alternative radiological modality for the assessment of bronchiectasis. Jung et al.3 concluded that low-dose volumetric helical CT at 40 mA potentially provides more diagnostic information than HRCT in the evaluation of bronchiectasis.

In line with advancements in several medical fields, progress is being made in the development of algorithms utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) for both studying and monitoring patients with bronchiectasis. An example of a possible application of these developments is the assessment of the artery-airway diameter ratio (AAR). Although we can easily observe the AAR with CT, the process is time-consuming and usually focuses on a limited number of airway sections. The integration of AI and automated systems is expected to replace labor-intensive manual scoring, enhancing reproducibility, speed, and potentially improving cost-effectiveness.4, 5

Different strategies are also being explored to reduce the CT-related radiation risk, especially in younger populations undergoing repeated imaging, such as patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) or primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). Ultra-low dose chest CT in adult patients with CF has proven to be useful in reducing radiation exposure of volumetric examinations.6 Nevertheless, further research is needed for its application in other populations. Additionally, MRI, despite its technical difficulties and the fact that most of the evidence is also in CF patients, is emerging as an alternative. It offers good sensitivity for the diagnosis of bronchiectasis, and may even provide information regarding lung function.7 However, few studies have been conducted comparing CT and MRI, and no proper reference data for bronchiectasis are available.4 Pending thorough validation studies, it is crucial to consider this limitation when interpreting bronchiectasis-related findings in MRI.

Finally, it is important to mention recent advances in PCD diagnosis.8 Although there is no definite consensus between European Respiratory Society (ERS)9 and American Thoracic Society (ATS)10 guidelines, nasal nitric oxide, motion analysis by high-speed videomicroscopy (HSVM), ciliary (ultra) structure analysis by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and genetic testing are still the most recommended evaluations. Recently developed procedures such as immunofluorescence and air liquid-interface cell cultures may also be helpful to differentiate PCD from secondary dyskinesia.11 However, these methods require high levels of expertise, and their cost and availability vary among diagnostic centers, even within a country, requiring adapted algorithms.12 An internationally harmonized, adapted and standardized diagnostic algorithm is needed to prevent PCD underdiagnosis.

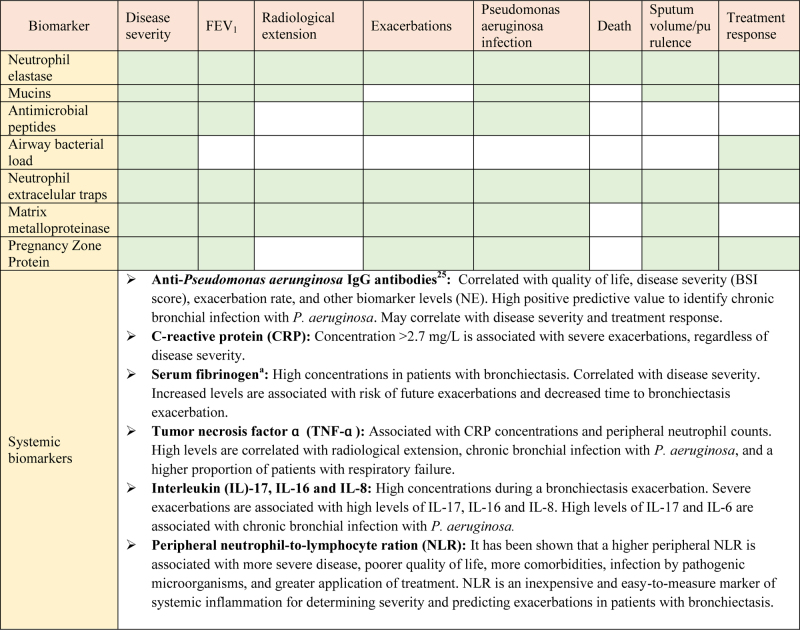

Are there any useful biomarkers of inflammation and disease severity in bronchiectasis?

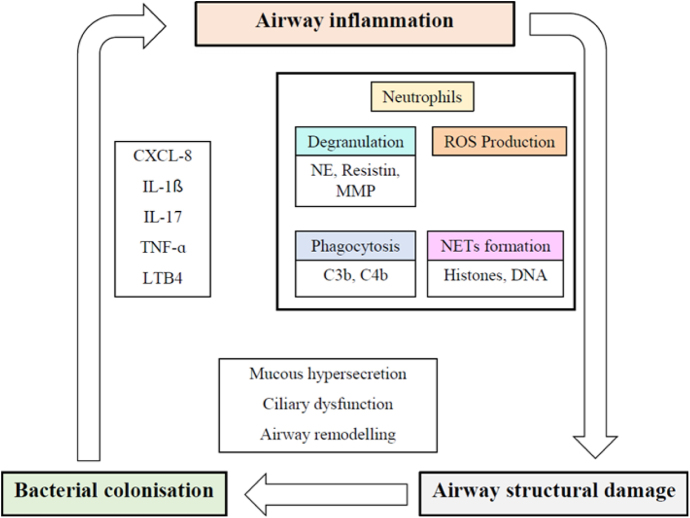

Neutrophilic inflammation plays a key role in the pathophysiology and progression of bronchiectasis (Fig. 2). The dysregulated inflammatory response results in lung damage, abnormal and irreversible dilatation of the bronchi, and recurrent respiratory infections.13, 14, 15 Biomarkers are needed to categorize and measure the biological activity of this disease. In this regard, the concept of “treatable traits” was defined to identify distinct clinical phenotypes and individualize treatments to achieve the best clinical outcomes in patients with bronchiectasis.16 Several studies have analyzed different systemic and local biomarkers, but only a few of them have demonstrated strong potential (Table 1).16

Fig. 2.

The vicious cycle hypothesis of bronchiectasis. CXCL-8: interleukin-8; IL-1β: interleukin-1 β; IL-17: interleukin 17; LTB4: leukotriene B4; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; NE: neutrophil elastase; NET: neutrophil extracellular traps; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α.

Table 1.

Main results of biomarkers in sputum and peripheral blood studies in bronchiectasis patients.

Neutrophil elastase (NE) is a proinflammatory protease with antimicrobial function, stored in azurophilic granules and released during degranulation by neutrophils. NE slows ciliary beat frequency and stimulates mucus secretion. Patients with bronchiectasis have high concentrations of NE in sputum, and its activity is correlated with disease severity (Bronchiectasis Severity Index, BSI), dyspnea, radiological extension, pulmonary function as measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and mortality. NE levels also increase in patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and during exacerbations, and decrease with the use of antibiotic treatment.16, 17, 18 To date, NE is the biomarker that has shown best results for the assessment of bronchiectasis patients. Furthermore, recent efforts have been made to reduce this neutrophilic inflammation, particularly NE levels, with promising results.19

Different local markers have also shown their usefulness in bronchiectasis evaluation. Mucins are glycoproteins that form the mucus, and play a key role in antibacterial defense of the airway. MUC5AC, MUC5B and MUC2 are the major secreted mucins detected in sputum. Recent studies show that their levels may also play a role in the pathogenesis of airway infection in bronchiectasis, and they may be used as a possible therapeutic target.16, 20

Antimicrobial peptides are innate immune molecules with antimicrobial (secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor, SLPI) or proinflammatory (lysozyme, lactoferrin and cathelicidin LL-37) functions. Their dysregulation perpetuates airway inflammation and may be associated with disease severity-phenotype and future risk of exacerbations.16, 21, 22

On the other hand, although it is not a biomarker per se, bacterial load shows a direct correlation with levels of local and systemic markers, and plays an important part in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. It may even be useful to identify patients with higher disease severity, and to predict therapeutic response.16

Another relevant marker is the formation of neutrophilic extracellular traps (NETs). NETs are a meshwork of extracellular fibers composed of chromatin DNA, histones, and bactericidal proteins, released by neutrophils to immobilize and disarm pathogens. This process is emerging as a key mechanism in airway inflammation and pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. They have also been shown to be useful for measuring disease severity and predicting treatment response in bronchiectasis.16, 22

Other biomarkers, such as matrix metalloproteinases and the pregnancy zone protein have also demonstrated significant associations with disease severity, exacerbations and quality of life, among others, but further studies are needed in order to better understand their role in bronchiectasis.23, 24, 25, 26

Are there endotypes in bronchiectasis?

Recent observations have shown that categorizing bronchiectasis patients based on a heterogeneous group of endotypes could be more effective, allowing for the development of more specific therapies to effectively treat our patients.

Various methods exist for classifying patients into different endotypes, with the most common approach being based on their comorbidities or underlying causes (Table 2).27 An alternative classification method considers the inflammatory mechanism, distinguishing between neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation.

Table 2.

Endotypes in bronchiectasis deriving from their comorbidities or underlying causes.

| Comorbidities or underlying causes | Clinical features | Underlying biological features |

|---|---|---|

| COPD | Smoking history Airflow obstruction |

Endotypes based on proteome and microbiome. |

| Asthma | Most frequent BE-associated comorbidities Bronchial hyperresponsiveness Variable airflow obstruction Frequent exacerbations Heterogenous disease with multiple endotypes |

Th2-driven inflammation or less commonly neutrophilic. |

| GORD | Frequent exacerbations Greater radiological extent Pulmonary microaspiration Gram-negative pathogens |

Neutrophilic inflammation Proteobacteria dysbiosis. |

| IBD | Large airway involvement Large sputum volumes Negative sputum cultures Female gender |

A shared lymphocytic inflammation between lungs and gut. |

| Primary immunodeficiency | Infections since childhood Underdiagnosed cause Most commonly CVID |

Multiple genes involved Neutrophilic inflammation. |

| Secondary immunodeficiency | Infections with onset at any age Underdiagnosed cause |

Iatrogenic immunosuppression Autoinmmune mechanisms |

| Systemic autoinmune diseases | Rapidly progressive disease Frequent exacerbations Prevalence of 20% in RA patients and from 7% to 54% in Sjögren syndrome |

Autoimmune features High risk of infections due to immunomodulating therapy |

| PCD | Underdiagnosed cause Early age of onset Heterogeneous disease Chronic rhinosinusitis Congenital cardiac defects Otitis media |

Multiple genes involved (DNAH5 most frequent defect) Neutrophilic inflammation |

| AATd | Panlobular emphysema in lower lobes Early onset Frequent exacerbations |

Abnormal AAT genotypes Neutrophilic inflammation |

| Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis | Wheezing Mucus plugging |

Elevated IgE Eosinophilic inflammation |

| Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection | Slowly progressive dyspnea Weight loss |

Immunosupression Impaired mucociliary clearance |

Modified from Martins et al.26 COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BE: bronchiectasis; GORD: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: IBD: inflammatory bowel diseases; CVID: common variable immunodeficiency; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; PCP: primary ciliary dyskinesia; AATd: alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

Adapted from Martins et al.26 AATd: alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency; BE: bronchiectasis; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVID: common variable immunodeficiency; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; PCP: primary ciliary dyskinesia; RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

As previously mentioned, neutrophils are the predominant cell type, and are dysfunctional in patients with bronchiectasis. The formation of NETs is a crucial part of the body's defense mechanism to eliminate pathogenic microorganisms. However, excessive NET production can lead to tissue damage and persistent airway inflammation. NETs release a large amount of enzymes, including NE, which contributes to tissue degranulation, impaired bacterial clearance, and increased mucus production.23 Consequently, they have distinct prognostic implications, indicating a promising avenue for tailored treatment strategies.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchiectasis are two different diseases with overlapping clinical presentation. Patients are frequently diagnosed with both diseases, and this is termed “COPD-bronchiectasis association”. Huang et al.28 recently demonstrated that patients with COPD and “COPD-bronchiectasis association” presented different profiles in their lung microbiota and host responses. Lung microbiota of the latter group was closer to that of bronchiectasis patients. The authors suggested classifying patients with COPD, bronchiectasis and “COPD-bronchiectasis association” into 5 different endotypes according to their clinical, sputum microbiome and protein profiles, which may present “treatable traits”. The first proposed endotype is the diverse-protective endotype, which has the best prognosis. Second, the Haemophilus-proteolytic endotype is associated with Haemophilus infection, for which tetracyclines could be a theoretical treatment option. Third, the infected-epithelial response endotype has characteristics of bronchiectasis patients, such as gram-negative infection, and may benefit from macrolide treatment. Fourth is the proteobacteria-neutrophilic endotype, in which macrolides may also be beneficial, as this group also has similarities with bronchiectasis and excessive neutrophil activation with the formation of NETs. Finally, the Th2 endotype responds to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or other treatments targeting Th2 inflammation.29 Patients classified under the eosinophilic inflammation endotype will be described later.

Eosinophilic bronchiectasis: a different subtype?

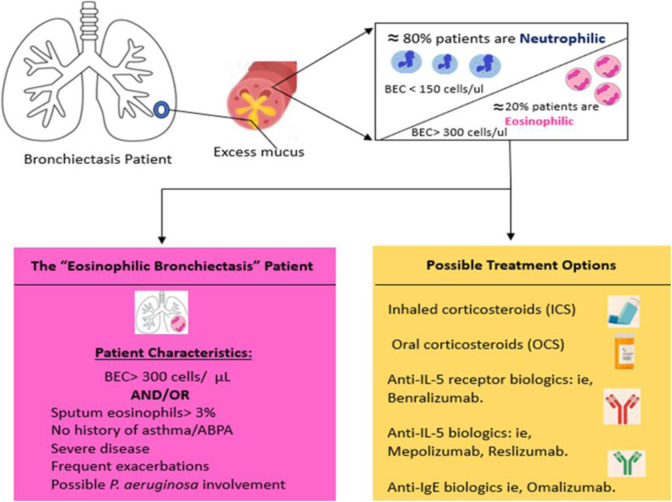

As mentioned earlier, an essential condition for the development of bronchiectasis is the presence of chronic bronchial inflammation, traditionally characterized by a predominantly neutrophilic profile.30 While most etiologies exhibit this pattern, bronchiectasis secondary to severe asthma and other eosinophilic diseases may demonstrate a preponderance of eosinophils.31

Few studies have assessed the type of inflammation in patients with bronchiectasis through bronchial biopsy or respiratory specimens. A seminal study compared bronchial biopsy samples between patients with bronchiectasis and healthy individuals, revealing an increase not only in neutrophilic infiltration, but also in eosinophils and mononuclear cells among patients with bronchiectasis as compared to controls.32

Eosinophilic inflammation represents a significant treatable trait characteristic in both asthma and COPD.33, 34, 35 Its presence and intensity correlate with a poorer disease prognosis, manifesting a higher frequency and severity of exacerbations. Moreover, it indicates a more favorable response to specific treatment, particularly with ICS.36, 37 Despite this, their use in bronchiectasis has historically been discouraged, except in cases where it coexists with the aforementioned diseases.33

Recent findings from national registries, such as RIBRON,38 and international databases like EMBARC,39 which focus on bronchiectasis, have revealed that up to 20% of bronchiectasis patients present peripheral eosinophilia with a blood eosinophil count of at least 300 eosinophils/mL or fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) ≥ 25 ppb. Notably, ICS have shown effectiveness in improving quality of life and mitigating the frequency and severity of exacerbations in these patients, even in the absence of asthma. In addition, this particular “subtype” is linked to a distinct airway microbiome characterized by a higher prevalence of chronic bronchial infections caused by Pseudomonas and Streptococcus.40

In the majority of case series, an increase in the severity and frequency of exacerbations was noted in both patients with a peripheral eosinophil count of at least 300 eosinophils/mL and those with a count ranging from less than 50 to 100 eosinophils/mL. However, in the latter group, bronchiectasis demonstrated increased severity across all established severity scales.41

While scientific evidence is currently limited, further studies in this field are warranted. This unique “subtype” of bronchiectasis, known as “eosinophilic bronchiectasis”, could potentially benefit from corticosteroid treatment, whether inhaled or oral. In cases resistant to conventional approaches, biological treatments may also be considered, akin to those employed in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma42 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Our current understanding of the patient with eosinophilic bronchiectasis and possible treatment options for this disease subset. ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; BEC: blood eosinophilic count.

Adapted from Pollock et al.43

In conclusion, eosinophilic bronchiectasis appears to represent a distinct and prevalent subtype of individuals, presenting unique prognostic factors and treatment considerations. Consequently, its recognition is imperative when managing patients with bronchiectasis.43

What is the role of the microbiome in bronchiectasis?

The microbiome is the set of genetic information of all microorganisms residing in a specific location.44 Whether in a state of health or disease, the preservation of immune homeostasis relies on the intricate interplay with microorganisms.45

The airway microbiome plays a pivotal role in the initiation, progression, and exacerbations of respiratory diseases.46 The “vicious cycle” or “vicious vortex” models propose a self-sustaining cycle involving infection, inflammation, impairment of mucociliary clearance, and persistent bacterial colonization, leading to the development of bronchiectasis.47, 48, 49

Using sequencing techniques, it has been observed that Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Veillonella, alongside benign commensal microorganisms, predominate in the microbiome of the healthy lung.50 This microbiome induces a proinflammatory Th17-type response that contributes to immune homeostasis.51 A higher prevalence of Pseudomonas, Haemophilus and Veillonella has been observed in bronchiectasis.52 Within anatomical distortion and immune dysregulation of the airway, commensal pathogens adopt the role of “pathobionts”, promoting the disease.53 The bronchiectasis microbiome is complex, comprising multiple bacterial species, and is personalized, remaining stable over time, even during exacerbations.54, 55

Bacterial diversity is associated with better clinical outcomes, reduced expression of inflammatory cytokines,56 and a positive correlation with lung function.57 Conversely, a decline in this diversity is linked to disease severity, impaired lung function,54 increased frequency of exacerbations, and a heightened risk of all-cause mortality.57 In bronchiectasis, microbiome dominance by Pseudomonas or Haemophilus is associated with elevated levels of inflammatory markers53, 55 and they have a mutually exclusive relationship.53

Although less extensively explored, fungi and viruses play a significant role in bronchiectasis. Within the microbiome, aspergillus, cryptococcus and clavispora are among the more prevalent. The presence of aspergillus has been associated with a higher frequency of exacerbations.58 In terms of the virome, influenza A and B, adenovirus, parainfluenza, rhinovirus and human T lymphotropic virus-1 have been identified59 with a consistently high frequency, even during periods of stability.60 Additionally, the potential role of bacteriophage viruses in maintaining microbiome stability should be noted61 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Concept of interactome: an integrated microbial network, where antibiotics affect inter-kingdom interactions.

Own elaboration.

Instead of targeting individual pathogens, antibiotics appear to exert a more significant impact on microbial interaction networks. This phenomenon could be explained by the influence of antibiotics on the interactome, affecting susceptible microbes that, in turn, modulate the virulence of the targeted, resistant pathogen.51, 62

There has been recent emphasis on adopting a holistic approach, focusing on the concept of a multibiome as an integrated microbial network, rather than viewing bacteria, fungi, and viruses as distinct entities. Relying solely on the detection of isolated microorganisms is deemed suboptimal for predicting exacerbation risks. As a potential therapeutic target, interactome analysis could be employed to identify alterations in inter-kingdom interactions during exacerbations.63, 64

Are there any new therapeutic developments in bronchiectasis?

Current treatments for bronchiectasis are aimed at specific treatable traits and preventable root causes, despite differences in underlying etiologies.65 The role of hypertonic saline (HS) in the management of bronchiectasis patients is crucial, as it promotes bronchial drainage, reduces mucus viscosity, enhances quality of life, and diminishes the frequency of exacerbations as well as antibiotic use.66 While the inhalation of 7% HS has been reported to be an effective strategy for mucus clearance, a significant number of patients show intolerance to this therapy. Enhancing HS with 0.1% hyaluronic acid has been found to improve patient tolerance toward HS treatment.67 An overview of the standard treatment approach for bronchiectasis is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of diverse therapeutic approaches for bronchiectasis.

| Therapeutic approach | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Secretion clearance | Therapies for bronchial clearance, respiratory physiotherapy, and postural drainage exercises. |

| 2. Pulmonary rehabilitation | Programs with exercises and education to improve lung function and quality of life. |

| 3. Vaccination | Immunization against respiratory diseases such as influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. |

| 4. Treatment of underlying causes | Identification and management of underlying causes, such as infections, obstructions, and gastroesophageal reflux. |

| 5. Low-dose macrolides | Use of macrolides to reduce the risk of exacerbations in selected cases. |

| 6. Inhaled antibiotics | Treatment with inhaled antibiotics to control bacterial infections. |

| 7. Anti-inflammatory therapies | Use of anti-inflammatory medications, such as brensocatib or monoclonal antibodies in specific cases. |

| 8. Eosinophilia management | Specific approach with inhaled corticosteroids or monoclonals for eosinophilic bronchiectasis. |

| 9. Mucolytic treatments | Medications reducing mucus viscosity, such as ARINA-1. |

| 10. Surgical evaluation | Consideration of surgical resection in localized and refractory cases. |

| 11. Lung transplantation | Reserved for end-stage bronchiectasis cases. |

Clinical trials of inhaled antibiotics reveal that reducing bacterial loads correlates with decreased exacerbation risks and symptom relief, highlighting the intricate interplay between bacterial load and respiratory symptoms.68 Nevertheless, non-antibiotic inhaled treatments can be helpful in the management of bronchiectasis patients. Inhaled mannitol has shown favorable outcomes in enhancing sputum properties and improving cough.69 Furthermore, ARINA-1, a novel nebulized therapy containing glutathione, sodium bicarbonate, and ascorbic acid, may help to reduce mucus layer viscosity in patients with bronchiectasis (NCT05495).

Regarding neutrophilic inflammation, brensocatib is a promising anti-inflammatory treatment for bronchiectasis that inhibits the activation of dipeptidylpeptidase-1 and neutrophil serine proteases.70 The phase 2 WILLOW study in 2020 demonstrated its effectiveness in prolonging time to the first exacerbation, reducing NE in sputum, and lowering exacerbation risk over 24 weeks.19, 71 The ongoing phase 3 ASPEN study aims to further assess brensocatib's risk-benefit profile with a larger sample size and an extended 52-week follow-up (NCT04594369).

In eosinophilic bronchiectasis, a combined analysis of 2 trials found that patients with peripheral blood eosinophilia, but without asthma, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), or COPD, experienced fewer exacerbations and hospitalizations after 6 months of ICS treatment.72 Another analysis showed mixed results, indicating that inhaled fluticasone, but not budesonide, significantly improved quality of life in these patients.73

Other treatments include monoclonal antibodies targeting elevated Th2 inflammation, such as anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-5 receptor monoclonal antibodies. These are novel and potentially efficacious treatments for bronchiectasis patients with blood eosinophilia ≥ 300 cells μL−1. Promising outcomes have been reported, including improved lung function, enhanced quality of life, and reduced exacerbation frequency.42 Similarly, gremubamab, a human immunoglobulin G1 kappa monoclonal antibody, is undergoing a phase 2 trial comparing it to placebo in participants with bronchiectasis and chronic P. aeruginosa infection.74

In summary, efforts are currently focused on developing new and promising treatments that have the potential to significantly enhance the management of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis patients.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received any financial support for preparation of this article.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have contributed to the preparation, review and drafting of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to the subject matter.

References

- 1.Aliberti S., Goeminne P.C., O’Donnell A.E., Aksamit T.R., Al-Jahdali H., Barker A.F., et al. Criteria and definitions for the radiological and clinical diagnosis of bronchiectasis in adults for use in clinical trials: international consensus recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10:298–306. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martínez-García M.Á., Máiz L., Olveira C., Girón R.M., de la Rosa D., Blanco M., et al. Spanish guidelines on the evaluation and diagnosis of bronchiectasis in adults. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2018;54:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung K.-J., Lee K.S., Kim S.Y., Kim T.S., Pyeun Y.S., Lee J.Y. Low-dose, volumetric helical CT: image quality radiation dose, and usefulness for evaluation of bronchiectasis. Investig Radiol. 2000;35:557–563. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Díaz A.A., Nardelli P., Wang W., San José Estépar R., Yen A., Kligerman S., et al. Artificial intelligence-based CT assessment of bronchiectasis: the COPDGene study. Radiology. 2023;307:e221109. doi: 10.1148/radiol.221109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meerburg J.J., Veerman G.D.M., Aliberti S., Tiddens H.A.W.M. Diagnosis and quantification of bronchiectasis using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2020;170:105954. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tagliati C., Lanza C., Pieroni G., Amici L., Carotti M., Giuseppetti G.M., et al. Ultra-low-dose chest CT in adult patients with cystic fibrosis using a third-generation dual-source CT scanner. Radiol Med. 2021;126:544–552. doi: 10.1007/s11547-020-01304-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pakzad A., Jacob J. Radiology of bronchiectasis. Clin Chest Med. 2022;43:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoemark A., Harman K. Primary ciliary dyskinesia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42:537–548. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucas J.S., Barbato A., Collins S.A., Goutaki M., Behan L., Caudri D., et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1601090. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01090-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro A.J., Davis S.D., Polineni D., Manion M., Rosenfeld M., Dell S.D., et al. Diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia: an official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:e24–e39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201805-0819ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nussbaumer M., Kieninger E., Tschanz S.A., Savas S.T., Casaulta C., Goutaki M., et al. Diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia: discrepancy according to different algorithms. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7:00353–2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00353-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shoemark A., Dell S., Shapiro A., Lucas J.S. ERS and ATS diagnostic guidelines for primary ciliary dyskinesia: similarities and differences in approach to diagnosis. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1901066. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01066-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keir H.R., Chalmers J.D. Pathophysiology of bronchiectasis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42:499–512. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solarat B., Perea L., Faner R., De La Rosa D., Martínez-García M.Á., Sibila O. Pathophysiology of chronic bronchial infection in bronchiectasis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2023;59:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chalmers J.D., Hill A.T. Mechanisms of immune dysfunction and bacterial persistence in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Mol Immunol. 2013;55:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suárez-Cuartín G., Sibila O. Local and systemic inflammation in bronchiectasis. Endotypes and biomarkers. Open Respir Arch. 2020;2:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.opresp.2020.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalmers J.D., Moffitt K.L., Suarez-Cuartin G., Sibila O., Finch S., Furrie E., et al. Neutrophil elastase activity is associated with exacerbations and lung function decline in bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1384–1393. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1027OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoemark A., Cant E., Carreto L., Smith A., Oriano M., Keir H.R., et al. A point-of-care neutrophil elastase activity assay identifies bronchiectasis severity, airway infection and risk of exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1900303. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00303-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalmers J.D., Haworth C.S., Metersky M.L., Loebinger M.R., Blasi F., Sibila O., et al. Phase 2 trial of the DPP-1 inhibitor brensocatib in bronchiectasis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2127–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sibila O., Suarez-Cuartin G., Rodrigo-Troyano A., Fardon T.C., Finch S., Mateus E.F., et al. Secreted mucins and airway bacterial colonization in non-CF bronchiectasis. Respirology. 2015;20:1082–1088. doi: 10.1111/resp.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sibila O., Perea L., Cantó E., Shoemark A., Cassidy D., Smith A.H., et al. Antimicrobial peptides, disease severity and exacerbations in bronchiectasis. Thorax. 2019;74:835–842. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perea L., Cantó E., Suarez-Cuartin G., Aliberti S., Chalmers J.D., Sibila O., et al. A cluster analysis of bronchiectasis patients based on the airway immune profile. Chest. 2021;159:1758–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keir H.R., Shoemark A., Dicker A.J., Perea L., Pollock J., Giam Y.H., et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps, disease severity, and antibiotic response in bronchiectasis: an international, observational, multicohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:873–884. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30504-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan W., Gao Y., Xu G., Lin Z., Tang Y., Gu Y., et al. Sputum matrix metalloproteinase-8 and -9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 in bronchiectasis: clinical correlates and prognostic implications. Respirology. 2015;20:1073–1081. doi: 10.1111/resp.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finch S., Shoemark A., Dicker A.J., Keir H.R., Smith A., Ong S., et al. Pregnancy zone protein is associated with airway infection neutrophil extracellular trap formation, and disease severity in bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:992–1001. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201812-2351OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suarez-Cuartin G., Smith A., Abo-Leyah H., Rodrigo-Troyano A., Perea L., Vidal S., et al. Anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa IgG antibodies and chronic airway infection in bronchiectasis. Respir Med. 2017;128:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins M., Keir H.R., Chalmers J.D. Endotypes in bronchiectasis: moving towards precision medicine. A narrative review. Pulmonology. 2023;29:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2023.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang J.T.-J., Cant E., Keir H.R., Barton A.K., Kuzmanova E., Shuttleworth M., et al. Endotyping chronic obstructive pulmonary disease bronchiectasis, and the “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-bronchiectasis association.”. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206:417–426. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1943OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long M.B., Chalmers J.D. Treating neutrophilic inflammation in airways diseases. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:463–465. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddel H.K., Bacharier L.B., Bateman E.D., Brightling C.E., Brusselle G.G., Buhl R., et al. Global initiative for asthma strategy 2021 Executive summary and rationale for key changes. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaga M., Bentley A.M., Humbert M., Barkans J., O’Brien F., Wathen C.G., et al. Increases in CD4+ T lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and interleukin 8 positive cells in the airways of patients with bronchiectasis. Thorax. 1998;53:685–691. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.8.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martínez-García M.Á., Oscullo G., García-Ortega A., Matera M.G., Rogliani P., Cazzola M. Inhaled corticosteroids in adults with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: from bench to bedside. A narrative review. Drugs. 2022;82:1453–1468. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01785-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald V.M., Gibson P.G. Treatable traits in asthma and COPD. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;58:583–585. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agusti A., Bel E., Thomas M., Vogelmeier C., Bruselle G., Holgate S., et al. Treatable traits: toward precision medicine of chronic airway diseases. Eur Resp J. 2016;47:410–419. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01359-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plaza V., Alobid l., Álvarez C., Blanco M., Ferreira J., García G., et al. Spanish asthma management guidelines (GEMA) VERSION 5.1. Highlights and controversies. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miravitlles M., Calle M., Molina J., Almagro P., Gómez J.T., Trigueros J.A., et al. Spanish COPD guidelines (GesEPOC)2021: updated pharmacological treatment of stable COPD. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martínez-García M.Á., Olveira C., Girón R., García-Clemente M., Maíz L., Sibila O. Reliability of blood eosinophil count in steady-state bronchiectasis. Pulmonology. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2023.11.006. S2531043723002040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-García M.A., Villa C., Dobarganes Y., Girón R., Maíz L., García-Clemente M., et al. RIBRON: The Spanish online bronchiectasis registry. Characterization of the first 1912 patients. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;57:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chalmers J.D., Polverino E., Crichton M.L., Ringshausen F.C., De Soyza A., Vendrell M., et al. Bronchiectasis in Europe: data on disease characteristics from the European Bronchiectasis registry (EMBARC) Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:637–649. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoemark A., Shteinberg M., De Soyza A., Haworth C.S., Richardson H., Gao Y., et al. Characterization of eosinophilic bronchiectasis: a European multicohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:894–902. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1889c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez-García M.A., Méndez R., Olveira C., Girón R., García-Clemente M., Maíz L., et al. The U-shaped relationship between eosinophil count and bronchiectasis severity: the effect of inhaled corticosteroids. Chest. 2023;164:606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rademacher J., Konwert S., Fuge J., Dettmer S., Welte T., Ringshausen F.C. Anti-IL5 and anti-IL5Ra therapy for clinically significant bronchiectasis with eosinophilic endotype: a case series. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901333. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01333-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollock J., Goeminne P.C. Eosinophils in bronchiectasis. Chest. 2023;164:561–563. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson R.L., de Koff E.M., Bogaert D. Characterising the respiratory microbiome. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801711. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01711-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young V.B. The role of the microbiome in human health and disease: an introduction for clinicians. BMJ. 2017:j831. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Budden K.F., Shukla S.D., Rehman S.F., Bowerman K.L., Keely S., Hugenholtz P., et al. Functional effects of the microbiota in chronic respiratory disease. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:907–920. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cole P.J. Inflammation: a two-edged sword – the model of bronchiectasis. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1986;147:6–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flume P.A., Chalmers J.D., Olivier K.N. Advances in bronchiectasis: endotyping, genetics, microbiome, and disease heterogeneity. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;392:880–890. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31767-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chalmers J.D., Chang A.B., Chotirmall S.H., Dhar R., McShane P.J. Bronchiectasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:45. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dickson R.P., Erb-Downward J.R., Huffnagle G.B. Homeostasis and its disruption in the lung microbiome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309:L1047–L1055. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00279.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vareille-Delarbre M., Miquel S., Garcin S., Bertran T., Balestrino D., Evrard B., et al. Immunomodulatory effects of Lactobacillus plantarum on inflammatory response induced by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2019;87:e00570–e619. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00570-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers G.B., Bruce K.D., Martin M.L., Burr L.D., Serisier D.J. The effect of long-term macrolide treatment on respiratory microbiota composition in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: an analysis from the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled BLESS trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:988–996. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogers G.B., Zain N.M.M., Bruce K.D., Burr L.D., Chen A.C., Rivett D.W., et al. A novel microbiota stratification system predicts future exacerbations in bronchiectasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:496–503. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-335OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woo T.E., Lim R., Heirali A.A., Acosta N., Rabin H.R., Mody C.H., et al. A longitudinal characterization of the non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis airway microbiome. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6871. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42862-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cox M.J., Turek E.M., Hennessy C., Mirza G.K., James P.L., Coleman M., et al. Longitudinal assessment of sputum microbiome by sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis patients. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0170622. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor S.L., Rogers G.B., Chen A.C.-H., Burr L.D., McGuckin M.A., Serisier D.J. Matrix metalloproteinases vary with airway microbiota composition and lung function in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:701–707. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-513OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rogers G.B., Van Der Gast C.J., Cuthbertson L., Thomson S.K., Bruce K.D., Martin M.L., et al. Clinical measures of disease in adult non-CF bronchiectasis correlate with airway microbiota composition. Thorax. 2013;68:731–737. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dicker A.J., Lonergan M., Keir H.R., Smith A.H., Pollock J., Finch S., et al. The sputum microbiome and clinical outcomes in patients with bronchiectasis: a prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:885–896. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mac Aogáin M., Chandrasekaran R., Lim A.Y.H., Low T.B., Tan G.L., Hassan T., et al. Immunological corollary of the pulmonary mycobiome in bronchiectasis: the CAMEB study. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800766. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00766-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao Y.-h., Guan W., Xu G., Lin Z.-y., Tang Y., Lin Z.-m., et al. The role of viral infection in pulmonary exacerbations of bronchiectasis in adults. Chest. 2015;147:1635–1643. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mitchell A.B., Mourad B., Buddle L., Peters M.J., Oliver B.G.G., Morgan L.C. Viruses in bronchiectasis: a pilot study to explore the presence of community acquired respiratory viruses in stable patients and during acute exacerbations. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:84. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0636-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Santiago-Rodriguez T.M., Hollister E.B. Human virome and disease: high-throughput sequencing for virus discovery identification of phage-bacteria dysbiosis and development of therapeutic approaches with emphasis on the human gut. Viruses. 2019;11:656. doi: 10.3390/v11070656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vandeplassche E., Tavernier S., Coenye T., Crabbé A. Influence of the lung microbiome on antibiotic susceptibility of cystic fibrosis pathogens. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28:190041. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0041-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mac Aogáin M., Narayana J.K., Tiew P.Y., Ali N.A.B.M., Yong V.F.L., Jaggi T.K., et al. Integrative microbiomics in bronchiectasis exacerbations. Nat Med. 2021;27:688–699. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boaventura R., Sibila O., Agusti A., Chalmers J.D. Treatable traits in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1801269. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01269-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martínez-García M.Á., Máiz L., Olveira C., Girón R.M., de la Rosa D., Blanco M., et al. Normativa sobre el tratamiento de las bronquiectasias en el adulto. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Máiz L., Girón R.M., Prats E., Clemente M.G., Polverino E., Caño S., et al. Addition of hyaluronic acid improves tolerance to 7% hypertonic saline solution in bronchiectasis patients. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1177/1753466618787385. 175346661878738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haworth C.S., Bilton D., Chalmers J.D., Davis A.M., Froehlich J., Gonda I., et al. Inhaled liposomal ciprofloxacin in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis and chronic lung infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ORBIT-3 and ORBIT-4): two phase 3, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:213–226. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bilton D., Daviskas E., Anderson S.D., Kolbe J., King G., Stirling R.G., et al. Phase 3 randomized study of the efficacy and safety of inhaled dry powder mannitol for the symptomatic treatment of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Chest. 2013;144:215–225. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palmér R., Mäenpää J., Jauhiainen A., Larsson B., Mo J., Russell M., et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 1 inhibitor AZD7986 induces a sustained exposure-dependent reduction in neutrophil elastase activity in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;104:1155–1164. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chalmers J.D., Metersky M.L., Feliciano J., Fernandez C., Teper A., Maes A., et al. Benefit–risk assessment of brensocatib for treatment of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9:00695–2022. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00695-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Martinez-Garcia M.A., Posadas T., Sotgiu G., Blasi F., Saderi L., Aliberti S. Role of inhaled corticosteroids in reducing exacerbations in bronchiectasis patients with blood eosinophilia pooled post-hoc analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. Respir Med. 2020;172:106127. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aliberti S., Sotgiu G., Blasi F., Saderi L., Posadas T., Martinez Garcia M.A. Blood eosinophils predict inhaled fluticasone response in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2000453. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00453-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chastre J., François B., Bourgeois M., Komnos A., Ferrer R., Rahav G., et al. Safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics of gremubamab (MEDI3902), an anti-Pseudomonas aeruginosa bispecific human monoclonal antibody, in P. aeruginosa-colonised, mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients: a randomised controlled trial. Crit Care. 2022;26:355. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04204-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]